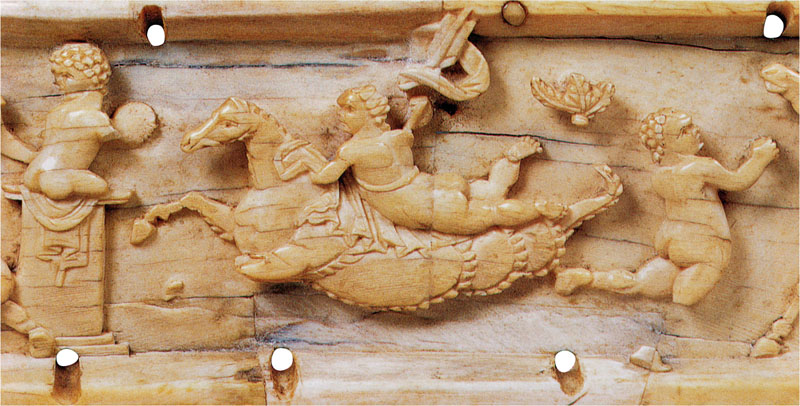

Chest-plate with a mythological decoration:

The Games of Putti (detail), Constantinople, 10th century.

Ivory, 28.2 x 4.8 cm. Musée du Louvre, Paris.

But nowhere has ivory been worked more perseveringly or with greater enthusiasm than in Germany. Here, as in Italy, the very greatest names are associated with this art. In the Cluny we find the medallion portraits vie with the most finished works in lithographic stone and wood, while artists display their ingenuity in multiplying the applications of this material. Shaped into circular forms and carved with subjects with women and children, and riotous bacchanalian scenes in which Silenus and the satyrs play a prominent part, the ivory was fashioned into goblets, pitchers, and other drinking vessels, richly mounted in silver. Elsewhere it is employed for the handles of carving knives, forks, spoons, as well as for portable knives. The ornamental bas-reliefs are without number while game pieces, boxes, and snuff boxes are met with in endless variety.

We have yet to mention the works of a particular country because there, more than elsewhere, it is extremely difficult to distinguish between history and legend. We refer, of course, to Spain, where painting especially has been highly cultivated. The marvellous expression of the features, the picturesque motion of the figures, the pliancy and truth of the draperies, cause Spanish sculpture to vie with the most perfect and carefully conceived works of the painter in religious fervour and in faithful imitation of real life. A fairly recently rediscovered statue of St Francis of Assisi, copied from a wood work by Alonzo Cano, gives some idea of the power the artist has to make the vegetable fibre quiver beneath the ecstatic inspiration of his chisel. And if we well remember a certain small ivory figure of St Sebastian, admirable in the cabinet of Thiers and shown as a work by the same painter, we must recognise in it the same knowledge and genial power, and admit that the suggestion of both being by the same hand no longer causes us any surprise. It is, at any rate, certain that most of the Spanish ivories in our collections are specially distinguished by their expression and, we might almost say, by their colour. Should we conclude that they are the work of painters, or else that the Spanish sculptors share the qualities of the painter?

Of course, one will note that our descriptions have been restricted more particularly to the ivories in which expression is paramount, and to bas-reliefs and statuettes. The fact is that purely ornamental pieces are excessively rare. When ivory is fashioned into caskets, drinking-vessels, or chalices, it is nearly always accompanied with an ornamentation in which the human figure occupies the most prominent place. This is so true that even in the smallest objects, such as beads of rosaries or the game pieces for checkers or chess, we are surprised still to find, often in microscopic proportions, scenes from sacred history, the contemporary effigies or heroic representations.

The universal use of this material is amply shown in public collections. The Museum of Artillery contains sword handles, the stocks of cross-bows, powder-flasks, and horns, all in ivory; these latter often in real ivory, but occasionally also in stag’s-horn worked after the fashion of double-layered cameos. Handles of knives or forks, objects of female use or even of pure ornament, patch boxes, snuff boxes, everywhere and at all epochs, we find ivory so fashioned, ever ornamented by art. Hence, it makes large claims on the attention of the connoisseur, whether as a furnishing material or as a treasure suitable for a shelf or show case.