9

Mutual Admiration Society

It is of great importance for a man to know how he stands with his friends; at least, I think so. Through good report and through evil report, the voice of a friend has a wonder working power; and from the very hour we hear it, “the fever leaves us.”

—Henry Wadsworth Longfellow letter to George Washington Greene, June 5, 1836

I called it Hyperion, because it moves on high among clouds and stars, and expresses the various aspirations of the soul of man. It is all modelled on this idea, style and all. It contains my cherished thoughts for three years.

—Henry Wadsworth Longfellow letter to George Washington Greene, January 2, 1840

The first copies of Hyperion came off the presses in August 1839, an event of no small import as far as Henry was concerned, if only for the fact that it was done, finally, and out in the world. “This book is a reality; not a shadow, or a ghostly semblance of a book,” he informed Greene. “My heart has been put into the printing-press and stamped on the pages. Whatever the public may think of it, it will always be valuable to me, and to my friends because it is a part of me.” The finished product was an amalgamation of literary forms intended to accomplish several goals, the original ones—an introduction for American readers to the German Romantic writers Henry had discovered during his second trip to Europe, and a scenic tour of the many fabulous sights—were combined with a plot twist based on his failed quest for the affections of Fanny Appleton, presented in the guise of a fictional character he called Mary Ashburton.

The first mention in Henry’s journal of a published review came on October 1; unsigned, the piece had appeared in the Evening Mercantile Journal, a Boston newspaper, the gist of it an unflattering assertion that the author had written a “mongrel mixture of description and criticism, travels and bibliography, common-places clad in purple, and follies ‘with not a rag to cover them.’ ” Henry never responded publicly to negative criticism, and remained characteristically stolid in this instance. “Some one has made a savage onslaught upon Hyperion,” he wrote bemusedly in his journal, taking it all in stride. “What care I? Not one straw. He has pulled so hard that he has snapped the bow-string. He seems to be very angry. What an unhappy disposition he must have, to be so much annoyed!”

Hard on the heels of that notice came an unsigned review in Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine, a Philadelphia periodical edited by Edgar Allan Poe, who had chosen the moment to initiate a disparagement of Henry’s work he would come to call his own “Little Longfellow War.” His off-the-rails assault would continue well into the 1840s and include unfounded charges of plagiarism. There were other writers Poe disliked, but for reasons still unclear, he trained his heaviest artillery on Henry, whose stature and material success were steadily on the rise. Henry never denied that a good deal of what he did was “derivative” of European genres and meters he used as models, but the inference that he lifted texts outright was patently absurd, and has never been supported by any credible evidence. In 1846, Henry recorded having discovered that the image of a fallen star in his poem “Excelsior” was similar to one in “The Mocking-Bird” by the poet John Brainard, an unwitting circumstance, he maintained, but similar all the same. “Of a truth,” he added, “we cannot strike a spade into the soil of Parnassus, without disturbing the bones of some dead poet.”

Poe offered no specifics to support his trashing of Hyperion, though he was adamant that Henry’s days of public favor would be short-lived. “We have no design of commenting, at any length, upon what Professor Longfellow has written,” he declared. “We are indignant that he too has been recreant to the good cause. We, therefore, dismiss his Hyperion in brief. We grant him high qualities, but deny him the Future. In the present instance, without design, without shape, without beginning, middle, or end, what earthly object has the book accomplished?—what definite impression has it left?” Henry’s reputation ultimately did suffer, the most egregious victim of the modernist movement’s wholesale dismissal of traditional literary forms, a reality not lost on Poe’s apologists, who cite it as proof of his prescience in such matters, though the reality is more complex than that, having more to do with cultural politics and less with literary merit.

What Poe trumpeted publicly was not necessarily reinforced by what he advanced privately, either, especially evident in two letters he wrote to Henry a year and a half after his attack on Hyperion. Poe had just been named editor of Graham’s, successor to Burton’s Gentleman’s Magazine, with a national circulation then approaching forty thousand copies a month, and was eager to recruit Henry as a contributor. “I should be overjoyed,” he wrote, “if we could get from you an article each month—either poetry or prose—length and subject a discretion. In respect to terms we would gladly offer you carte blanche—and the periods of payment should also be made to suit yourself.” Poe expressed his “highest respect” for Henry’s work with words that can be read as hypocritical at best, obsequious at worst: “I cannot refrain from availing myself of this, the only opportunity I may ever have, to assure the author of the ‘Hymn to the Night,’ of the ‘Beleaguered City’ and of the ‘Skeleton in Armor’ of the fervent admiration with which his genius has inspired me.”

In declining the offer—“I am so much occupied at present that I could not do it with any satisfaction either to you or to myself”—Henry extended a palm leaf of sorts to Poe’s fawning confession that he had “no reason to think myself favorably known to you.” His reply: “You are mistaken in supposing that you are not ‘favorably known’ to me. On the contrary, all that I have read, from your pen, has inspired me with a high idea of your power; and I think you are destined to stand among the first romance-writers of the country, if such be your aim.” Poe’s follow-up attempted another tack—perhaps Henry might consider writing for another magazine his employer, George R. Graham, was then considering, but never launched? “The amplest funds will be embarked in the undertaking. The work will be an octavo of 96 pages. The paper will be of excellent quality—possibly finer than that upon which your Hyperion was printed.” Henry opened negotiations directly with George Graham the following year, after Poe left the magazine. They worked productively together on numerous projects, including The Spanish Student, a dramatic work in verse inspired by a Cervantes tale, and published in three consecutive issues of Graham’s Magazine.

Poe, meanwhile, intensified his attack, which Henry ignored with a silence that had to have been infuriating. He made no mention of him at all in his journal for three and a half years, and then only offhandedly, at a time when he was wondering what to call the heroine of a long narrative poem he had just started to write. “Shall it be ‘Gabrielle,’ ” he mused on December 7, 1845, “or ‘Celestine,’ or ‘Evangeline’?” Two days later he mentioned having just read “a very abusive article upon my poems” by William Gilmore Simms, a Southern author and a great favorite of Poe’s, who shared his views. “I consider this the most original and inventive of all his fictions.” The next day, he praised a “superb poem” by his friend James Russell Lowell that he had just read in Graham’s Magazine. “If he goes on in this vein,” he offered, “Poe will soon begin to pound him.”

A review in the New-York Daily Tribune on December 20 by Margaret Fuller, who never warmed to his work, either, drew what for Henry amounted to an annoyed response but, given the tenor of her scorn, is remarkable for its restraint. The “furious onslaught,” as Henry called the lengthy notice, had avowed him to be a poet of “moderate powers” with “no style of his own,” declaring further that little of what he wrote emerged from personal experience or observation. “Nature with him, whether human or external, is always seen through the window of literature. There are in his poems sweet and tender passages descriptive of his personal feelings, but very few showing him as an observer, at first hand, of the passions within, or the landscape without.” Henry had a single response: “It is what might be called ‘a bilious attack.’ She is a dreary woman.” Not one to hold a grudge, his attitude toward Fuller softened appreciably four years later when news spread that she had become a mother—and taken a husband ten years her junior—in that order. “We hear that Margaret Fuller is married in Italy, to a revolutionary marquis, secretly married a year ago, and has a baby! It will do her a prodigious deal of good.”

Henry usually preferred another kind of response to his critics. Two weeks after Fuller’s excoriation of his work had been published, he learned that “The Belfry of Bruges” was “succeeding famously well” in the marketplace, and that the poems “To a Child” and “The Old Clock on the Stairs” were popular with his admirers. “This,” he declared, “is the best answer to my assailants,” and left the matter there. The general public had also responded favorably to Hyperion. Over time it became a go-to handbook for travelers to the Rhineland, and an essential reference to German Romantic literature.

Numerous illustrated editions would appear in the years ahead, including one published in 1865 with twenty-four albumen prints of castles, villages, mountain glaciers, and literary sites across Germany, Switzerland, and Austria taken by the landscape photographer Francis Frith, qualifying it as the first printed book to feature photographic images. In 1918, the literary scholar W. A. Chamberlain called Henry the “foremost interpreter to the American public of German life for his generation,” and credited Hyperion for much of that success. James Taft Hatfield cited twenty-five German authors and poets whose works were introduced to American readers in Hyperion, including Goethe and Schiller.

Very rarely did the early critics discuss in any depth the autobiographical elements that deal with the Mary Ashburton character. Those that did, such as his good friend Cornelius Conway Felton in the sixteen-page review he wrote for The North American Review, did not connect the episode directly to the author. Paul Flemming is introduced in the early pages of the book as a grief-stricken American traveling through Europe, having recently lost the “friend of his youth,” the precise relationship vaguely stated, but the suggestion clear enough that it was spousal. “He could no longer live alone, where he had lived with her,” was the rationale for the trip abroad, a great distance from home necessary so that “the sea might be between him and the grave.”

As Hyperion opens, Flemming is “pursuing his way along the Rhine, to the south of Germany,” a region he remembered well from a previous journey. “He knew the beauteous river all by heart;—every rock and ruin, every echo, every legend. The ancient castles, grim and hoar, that had taken root as it were on the cliffs,—they were all his; for his thoughts dwelt in them, and the wind told him tales.” Significantly, it is the sound of Mary Ashburton’s voice, not her appearance, that first captures Flemming’s attention. He is aware of a “female figure, clothed in black” who enters a public gathering space in a Swiss inn where he is waiting to be assigned a room, and listens as she joins in a conversation with other guests, her words “spoken in a voice so musical and full of soul” that he calls it “a whisper from heaven.” Because it is twilight and the surroundings dark, he does not have an opportunity to match the sound with the face before he is called out by the landlord and directed to his assigned quarters.

Flemming later asks a friend he has made on the journey who the young lady “with the soft voice” was, and is told her name: Mary Ashburton. “Is she beautiful?” he asks, eliciting an answer that could not have pleased Miss Appleton one bit when she read it. “Not in the least,” he is told, “but very intellectual. A woman of genius, I should say.” Flemming swiftly backtracks on this crude assessment, pointing the finger elsewhere. “They did her wrong, who said she was not beautiful,” he insists, noting that Ashburton’s face has “a wonderful fascination in it,” a “calm, quiet face, with the light of the rising soul shining so peacefully” through it. “And O, those eyes,—those deep unutterable eyes.”

Fanny Appleton, we know from her passport, was five feet ten inches tall when she sailed for Europe—two inches taller than Henry—and carried herself with confidence. So endowed, too, was Mary Ashburton. “The lady’s figure was striking. Every step, every attitude was graceful, and yet lofty, as if inspired by the soul within. Angels in the old poetic philosophy have such forms; it was the soul itself imprinted on the air. And what a soul was hers! A temple dedicated to Heaven, and, like the Pantheon at Rome, lighted only from above.” Flemming thereupon spends a fortnight with Ashburton and her widowed mother, seizing every opportunity to be near the young woman, who, we are told, is “in her twentieth” year. “He conversed with her; and with her alone; and knew not when to go. All others were to him as if they were not there. He saw their forms, but saw them as the forms of inanimate things.”

Together, they translate into English a ballad by Uhland—“The Castle by the Sea,” the same poem rendered by Henry and Fanny, with the same result: the lady’s version being the better of the two. When the moment calls for a folk tale, Flemming invents one out of whole cloth. Ashburton matches Flemming insight for insight on topics of weight and significance, and enthralls him with her ability to draw evocative scenes in her sketchbook with assured ease. During one stop, Flemming is “reclining on the flowery turf, at the lady’s feet, looking up with dreamy eyes into her sweet face, and then into the leaves of the linden-trees overhead.”

We can only speculate on how mutual acquaintances in Boston and Cambridge responded to Henry’s public confession that his alter ego was “haunted” at all times of the day by thoughts of the young woman. “He walked as in a dream; and was hardly conscious of the presence of those around him. A sweet face looked at him from every page of every book he read; and it was the face of Mary Ashburton! A sweet voice spake to him in every sound he heard; and it was the voice of Mary Ashburton! Day and night succeeded each other, with pleasant interchange of light and darkness; but to him the passing of time was only as a dream. When he arose in the morning, he thought only of her, and wondered if she were yet awake; and when he lay down at night he thought only of her.” In the end, his intensity proves to be too much for Mary Ashburton. Flemming is sensibly advised to accept the harsh reality of failure and move along—the same advice Henry had received from his own support group. “I love this woman with a deep, and lasting affection,” Flemming counters in response. “I shall never cease to love her. This may be madness in me; but so it is.”

On Beacon Hill, the general reaction to Hyperion was silence, but in private, everyone knew who was who among the players. Writing to Fanny Calderón de la Barca in the summer of 1840, the historian William Hickling Prescott told how Fanny Appleton’s “bright eyes were filled with sadness” at a party he had recently attended in Newport, the absence of her sister Mary causing continued distress. “That separation has cost her a heartache—the only one I suspect she has ever known, for she walks ‘in maiden meditation, fancy free,’ and free in fact, I suspect, in spite of all poor Longfellow’s prose and poetry.”

Three years later, when there was a rapprochement, the tongues were wagging overtime. Inviting an acquaintance in New York to visit him in Massachusetts that summer, Charles Sumner noted that he would likely “find Longfellow a married man” when he arrived, “for he is now engaged to Miss Fanny Appleton,—the Mary Ashburton of Hyperion,—a lady of the greatest sweetness, imagination, and elevation of character, with the most striking personal charms.” Julia Ward Howe recalled after Henry’s death how well-known it had been years earlier that Fanny was “the supposed prototype of Mary Ashburton,” and that “conjectures were not wanting as to the possible progress and denouement of the real romance which seemed to underlie the graceful fiction. This romance indeed existed, and its hopes and aspirations were crowned in due time by a marriage which led to years of noble and serene companionship.”

That said, it would be a mistake to suggest that Henry was spending all his time pouting about his private life to the exclusion of everything else. Within the space of a single year, three works—Hyperion, his prose romance; Voices of the Night, his widely admired first collection of poetry; and The Spanish Student, his play in three parts—had appeared in print. Significant, too, as these three efforts indicate, is that he was working concurrently with different literary forms—an unacknowledged bow in the direction of Goethe, maybe, whose proficiency in multiple disciplines was an inspiration to him, the figurine of the German writer kept front and center on his writing desk a validation of that.

If there was solace to be found in the short run, it came from a group of professional people who provided support to Henry in many ways, including favorable notices several of them wrote of Hyperion for influential publications. On more than one occasion, this group would be anointed the Mutual Admiration Society, a description they all embraced. The friendships Henry firmed up at this time endured for the remainder of his life, most of them with men, but a few with women as well, most notably Julia Ward Howe, the brilliant sister of his friend Sam Ward; Catherine Eliot Norton, the wife of Andrews Norton; Annie Adams Fields, the wife of his longtime editor James T. Fields; and his landlady, Elizabeth Craigie, for whom he developed a special affection in the short time he knew her. If likability is innate, he had it in abundance, apparent from the briefest of encounters to the most cherished relationships. “Once your friend, Longfellow was always your friend; he would not think evil of you, and if he knew evil of you, he would be the last of all that knew it to judge you for it,” William Dean Howells wrote a few years after Henry’s death.

People extolled his knack for paying attention to what they had to say, and for never uttering anything he might one day regret having said. “A part of Mr. Longfellow’s charm was his way of listening; another charm was his beauty, which was remarkable,” the Boston socialite Mary E. W. Sherwood (1826–1903) wrote in an entertaining memoir of her many encounters with well-placed literary, social, and political figures of the nineteenth century. The portrait artist Wyatt Eaton (1849–96) recalled being “struck by the great intentness, almost a stare,” Henry had cast during the course of several sittings. “His eyes were so brilliant that he really seemed to be looking one through. It was this gaze that I tried to get in my portrait.”

The writer William Winter (1836–1917) regarded Henry as a mentor, so much in awe of him, according to Ernest Longfellow, that he was “too timid to refuse” his father’s offer of a cigar every time he came, “which invariably made him sick, so that he would have to retire to the garden.” Winter recalled a conversation he had with Henry about Edgar Allan Poe, by then long since deceased. “I was sitting with him, at his fireside, and when I chanced to observe a volume of Poe’s poems on his library table, I inquired whether he had ever met Poe and was assured that he had not. Longfellow opened the book and read aloud a few stanzas of the poem ‘For Annie,’ remarking that one of them, containing the line ‘And the fever called living is over at last,’ would be an appropriate epitaph for its writer. There was not a shade of resentment in either his manner or voice. ‘My works,’ he said, ‘seemed to give Mr. Poe much trouble; but I am alive and still writing.’ ” Henry then offered Winter some counsel. “You are at the beginning of your career, and I advise you never to answer the attacks that will be made on you,” the example of his own approach to Poe obviously implied. “I did not then know, but subsequently learned, he naturally attracted to himself all persons intrinsically noble. His gentleness was elemental. His tact was inerrant. His patience never failed. As I recall him, I am conscious of a beautiful spirit; a lovely life; a perfect image of continence, wisdom, dignity, sweetness, and grace.”

Winter was not aware—or if he was, he never let on in print—that there had been an extraordinary gesture of kindness on Henry’s part with respect to Poe, evident only by examination of his incoming correspondence and personal account books. In 1850, Henry received a letter from Maria Poe Clemm (1790–1871), both aunt and mother-in-law to Poe, since her “dear Eddy” had married his first cousin, Virginia, the daughter of this woman, who was the daughter of his paternal grandfather. Poe had died the previous year. “Muddy,” as Poe called her, was then living in Lowell, and wrote Henry, a total stranger, asking for help—a tactic she used with other writers, including Charles Dickens, who—like Henry—sent her small sums. Her letters to Henry, fifteen of them in the Houghton collections, are worth reading if only for the boldness she brought to bear, asking him to send, in addition to money, signed first editions of his books and autographs she could sell. That Henry did so—without commenting on it to anyone—is further evidence of his compassion and goodwill.

Given the number of best-selling books he had on the Ticknor and Fields front list in the days following the Civil War, Henry was a special client of the firm, according to Edwin D. Mead (1849–1937), who went to work for the publisher in 1866 as a low-level office assistant. It was not uncommon for Ralph Waldo Emerson, Harriet Beecher Stowe, John Greenleaf Whittier, Oliver Wendell Holmes, William Dean Howells, or Longfellow himself to visit their offices, by then relocated from the Old Corner Bookstore on Washington and School Streets to larger accommodations on Tremont. Henry was already an international celebrity when Mead came aboard, and whatever “concerned Longfellow concerned every boy at 124 Tremont Street.” Henry “knew us every one, every time,” he wrote. “His smile as he opened the door said: ‘Here we go again!’ and his entrance was always a benediction. As I now look back, his seems to me to be the noblest face and presence that I ever knew.”

Henry became acquainted with the classicist Cornelius Conway Felton (1808–1862) while still teaching at Bowdoin and arranging to get his textual translations published in Boston and Cambridge. Fluent in many languages, Felton taught at Harvard for more than thirty years. “As a Greek scholar,” a eulogist for the Smithsonian Institution wrote following his death, “he was not surpassed for breadth and accuracy by any other in the land.” Felton was named professor of Greek at Harvard in 1832, four years before Henry joined the faculty, and became Harvard’s president in 1860. He was a champion of Henry’s writing, even worked with him on his anthology of world poetry, and is thought by some, myself included, to have been the person who in 1845, under the pen name Outis (from the Greek word οὔτις, for “nobody”), wrote a brilliantly erudite defense against Poe’s spiteful charges of plagiarism, resulting, ultimately, in Poe’s retraction.

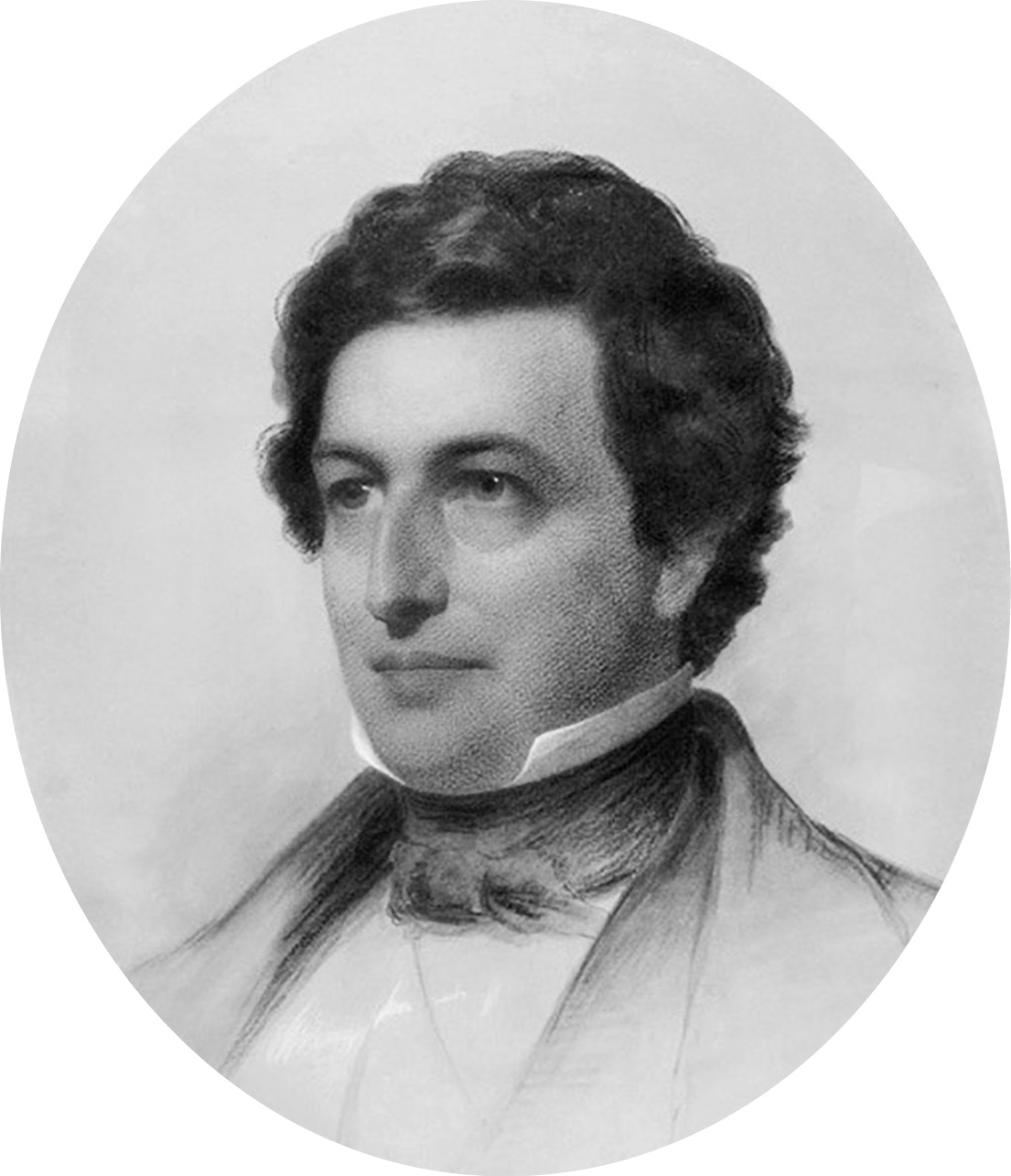

Cornelius Conway Felton, by Eastman Johnson, 1846, in the first-floor study of Longfellow House

It was Felton, too, who introduced Henry to Charles Sumner, a high-energy Boston lawyer who moonlighted for a time as a law instructor at Harvard and became, in time, Henry’s closest friend. Along with Sumner’s law partner, George Hillard, and Henry R. Cleveland, an aspiring writer, the men formed an informal social association they dubbed the Five of Clubs, and met regularly for dinner and conversation, usually at the Tremont House, leading one “ironical lady,” in the words of Julia Ward Howe, to dub them the Mutual Admiration Society, a nickname that found its way into the newspapers, and stuck.

Cleveland’s principal contribution was to ensure a proper ambiance for club gatherings, his largesse made possible by the happy circumstance of having married a wealthy socialite. In a posthumous tribute—he died in 1843 at the age of thirty-four—George Hillard described his “sweet” spirit as being driven by a “wide and generous hospitality” and an “almost maternal fondness and tenderness of feeling.” A staple of their Saturday soirees was freshly shucked oysters served with champagne, a tradition Henry continued several decades later when hosting meetings in his home of the Dante Club. Cleveland’s death opened the way for Samuel Gridley Howe to join their ranks. A practicing physician, abolitionist, and reformer, Howe achieved widespread fame for his work at the Perkins School for the Blind with Laura Bridgman, sightless and deaf from scarlet fever when she began instruction under his direction in 1837 at the age of seven. It was during a field trip to see Bridgman with Henry and Sumner that Julia Ward was introduced to her future husband.

George Washington Greene, recipient of close to six hundred letters from Henry over the four decades of their friendship, held a special place in the poet’s pantheon of intimates. Henry did not love him for his intellect, which was decent but by no means staggering, or his sage advice, since he typically was the one griping the most about the vicissitudes of life, and the one who needed the most assistance through the many years of their acquaintance. Henry loved Greene, it seems, simply because he was Greene, a fellow New Englander he had met in Marseilles when he was nineteen, the man who introduced him to Italy, the man who like himself had a grandfather who had fought honorably in the Revolution.

It was at this time, too, that Nathaniel Hawthorne reached out to his old college classmate, reminding him of their days a decade earlier as Bowdoin undergraduates. The two had never been close, but with just thirty-eight students in the class of 1825, they had crossed paths from time to time, even delivered honors orations once on the same program. Hawthorne would tell Annie Adams Fields many years later that “no two young men could have been more unlike” at Bowdoin; Henry, he told her, was a “tremendous student, and always carefully dressed, while he himself was extremely careless of his appearance, no student at all, and entirely incapable of appreciating Longfellow.” Impressed by the success of Outre-Mer, Hawthorne sent Henry a copy of Twice-Told Tales, his newly published book. “We were not, it is true, so well acquainted at college that I can plead an absolute right to inflict my ‘twice-told’ tediousness upon you,” he wrote frankly, “but I have often regretted we were not better known to each other, and have been glad of your success in literature and in more important matters.”

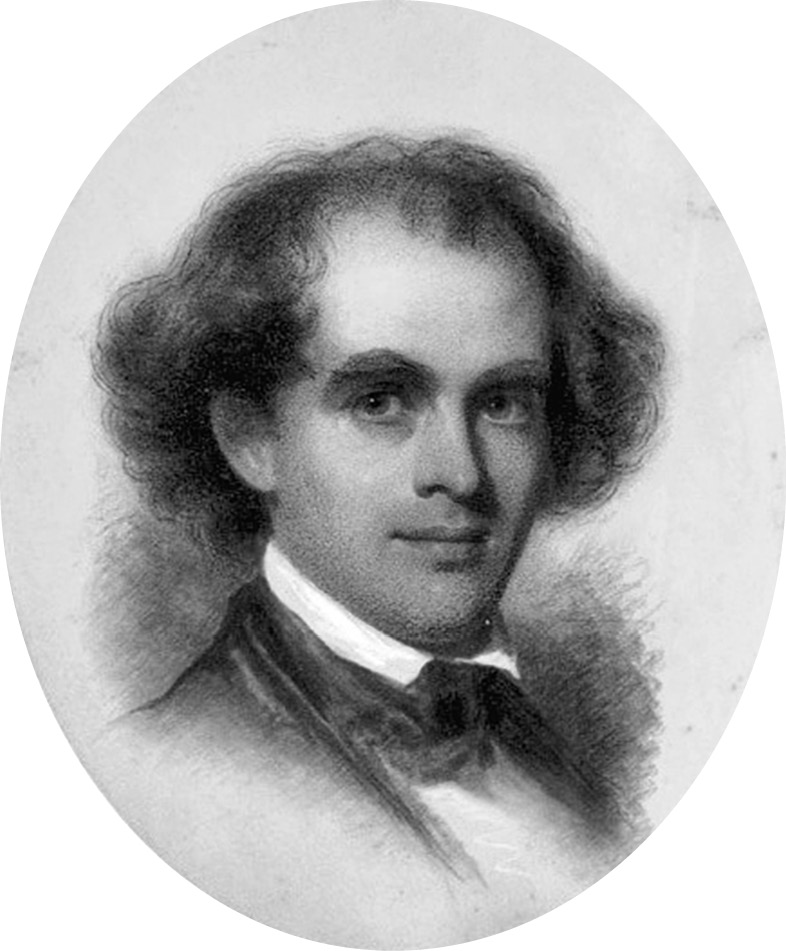

Nathaniel Hawthorne, 1846, by Eastman Johnson, in Henry’s study at Longfellow House

Henry responded in the best way possible—proclaiming the arrival of a major new talent in an effusive notice for The North American Review. “When a star rises in the heavens, people gaze after it for a season with the naked eye, and with such telescopes as they may find,” he wrote, using imagery likely inspired by talk of Harvard erecting a powerful observatory on property adjoining Craigie House. “In the stream of thought, which flows so peacefully deep and clear through this book, we see the bright reflection of a spiritual star, after which men will be prone to gaze ‘with the naked eye and with the spy-glasses of criticism.’ ” The immediate result was a friendship that held firm to the day Hawthorne died at the age of fifty-nine in 1864. Henry mourned “dear Nat’s” passing in his “Elegy for Hawthorne,” a nine-stanza poem that concluded with sadness for works left undone:

There in seclusion and remote from men

The wizard hand lies cold,

Which at its topmost speed let fall the pen,

And left the tale half told.

Ah! who shall lift that wand of magic power,

And the lost clew regain?

The unfinished windows in Aladdin’s tower

Unfinished must remain!

AS 1841 BECAME 1842, Henry was deeply depressed, suffering a case of the blues so severe that he had decided to take a “water-cure” in Germany to relieve his various ailments. Those plans were put on hold when word arrived from England that the celebrated author of Pickwick Papers, Oliver Twist, Nicholas Nickleby, and The Old Curiosity Shop—Charles Dickens—was coming to the United States for a series of public appearances, with the first stop of the tour being Boston. It was a testament to Henry’s growing stature as a literary lion in his own right that he was asked, along with Oliver Wendell Holmes, to coordinate a proper reception for the esteemed visitor, an opportunity they both embraced.

Dickens described to his close friend and future biographer, the critic John Forster, the frenzy that greeted his arrival in Boston. “How can I give you the faintest notion of my reception here; of the crowds that pour in and out the whole day; of the people that line the streets when I go out; of the cheering when I went to the theatre; of the copies of verses, letters of congratulation, welcomes of all kinds, balls, dinners, assemblies without end? There is to be a public dinner to me here in Boston, next Tuesday, and great dissatisfaction has been given to the many by the high price (three pounds sterling each) of the tickets.” Henry made an afternoon call on Dickens at the Tremont House, bringing with him Harvard colleagues Felton and Jared Sparks. Later that night, in letters to Sam Ward in New York and his father in Maine, Henry deemed the day to have been “glorious.” To his father, he added how Dickens was “engaged three deep for the remainder of his stay, in the way of dinners and parties.” He described him as “a gay, free and easy character” with blue eyes, long black hair, and a “fine bright face.”

Dickens readily accepted Henry’s invitation for a Sunday walking tour of the city, their route to parallel many of the spots along the harbor that now dot the heavily trod Freedom Trail historic district, including the wharf where the Boston Tea Party was staged by the Sons of Liberty in 1773; Charles Sumner accompanied them on the promenade. At the Seamen’s Bethel Church in the North End, they attended a sermon delivered by the fiery Methodist minister Edward Thompson Taylor, an outspoken advocate of the temperance movement, and renowned for his work on behalf of itinerant sailors. Leaving the chapel, they passed by Paul Revere’s house and the Old North Church, then proceeded into Charlestown and the Navy Yard, home port of the USS Constitution, immortalized by Holmes twelve years earlier as “Old Ironsides” in a poem that saved the frigate from the scrapyard.

At Copp’s Hill Burying Ground, they looked at the tombstone inscriptions of Revolutionary War dead; at Bunker Hill they admired the towering stone obelisk just being completed to memorialize the battle fought there in June 1775. What they discussed we can only surmise, but Henry may well have mentioned that two months before that momentous battle took place, General Washington had commandeered a house in Cambridge to serve as his headquarters and residence during the Siege of Boston, the very building where he was then living. Dickens, in any case, accepted Henry’s invitation to join him there the following Friday for breakfast.

Henry by then had three spacious rooms on the second floor, one ideal for receiving visitors. His invitation to Sam Ward brimmed with ebullience. “When shall you be here? Dickens breakfasts with me on Friday. Will you come? Let me know beforehand, every place at table is precious.” Ward could not make the “bright little breakfast,” as Sam Longfellow described it, but half a dozen Harvard bigwigs did break bread with the man of the hour. Dickens took a coach to Cambridge, and walked the half mile from Harvard Square—known then simply as the Market Place—to Craigie House. On the way over, he passed the “spreading chestnut tree” on Brattle Street made famous in “The Village Blacksmith,” which had appeared in The Knickerbocker a year earlier and was just being published in Henry’s second collection of verse, Ballads and Other Poems. They concluded the morning with a stroll over to Gore Hall, home then of the Harvard College library, where other admirers alerted in advance of the visit were waiting.

Informed of Henry’s evolving travel plans, Dickens minced no words about what stops he expected would be included on his itinerary: “My dear Longfellow,” he wrote from New York. “You are coming to England, you know. When you return to London, I shall be there, please God. Write to me from the continent, and tell me when to expect you. We live quietly—not uncomfortably—and among people whom I am sure you would like to know; as much as they would like to know you. Have no home but mine—see nothing in town on your way towards Germany—and let me be your London host and cicerone. Is this a bargain?”

TORMENTED THROUGHOUT his life by a variety of chronic ailments, Henry was forever seeking relief. Mentions of headaches, neuralgia, blurry eyesight, toothaches, dyspepsia, dizziness, colds, and insomnia turn up often in his journals and letters, though rarely to the point of forcing him to abandon his work ethic. An exception came on January 24, 1842, when he asked the Harvard Corporation for a six-month leave of absence to take a therapeutic “water-cure” and dietary program then being offered at a former Benedictine convent at Marienberg overlooking the town of Boppard on the Rhine. “In this time,” he wrote, “I propose to visit Germany, to try the effect of certain baths, by means of which, as well as by the relaxation and sea-voyage, I hope to re-establish my health.” School officials were not overly pleased by this, but granted the request; he got his six months, to begin in May. He would write just one piece of poetry that summer, a sonnet scrawled out on a sheet of scrap paper he called “Mezzo Cammin,” drawing his title from the opening line of Dante’s Inferno (“Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita”), which translates into English as “Half Journey.” The poem reflected harshly on what Henry felt he had accomplished in his first thirty-five years, and remained unpublished during his lifetime:

Half of my life is gone, and I have let

The years slip from me and have not fulfilled

The aspiration of my youth, to build

Some tower of song with lofty parapet.

Not indolence, nor pleasure, nor the fret

Of restless passions that would not be stilled,

But sorrow, and a care that almost killed,

Kept me from what I may accomplish yet;

Though, half-way up the hill, I see the Past

Lying beneath me with its sounds and sights,—

A city in the twilight dim and vast,

With smoking roofs, soft bells, and gleaming lights,—

And hear above me on the autumnal blast

The cataract of Death far thundering from the heights.

Henry did find sufficient time to go book hunting, advising Sumner that he had “dispatched” to Rotterdam “a large box of books to go by first ship” to Boston. “I know not how it is, but during a voyage I collect books as a ship does barnacles. These books are German, Flemish, and French.” Another bright spot was meeting the poet Ferdinand Freiligrath, who would translate many of Henry’s poems into German in the years to come. Freiligrath’s radical political views also influenced Henry to contribute, however mildly, to the cause of abolition back home. “Oh, I long for those verses on slavery,” Sumner had written from Boston. “Write some stirring words that shall move the whole land. Send them home and we’ll publish them. Let us know how you occupy yourself with that heavenly gift of invention.”

Henry’s response, jotted down during a break from his therapy, was noncommittal. “There is no inspiration in dressing and undressing,” he wrote of his daily routine. “Hunger and thirst figure too largely here, to leave room for poetical figures.” His mood brightened when he heard from Dickens: “Your bed is waiting to be slept in, the door is gaping hospitably to receive you, I am ready to spring towards it with open arms at the first indication of a Longfellow knock or ring; and the door, the bed, I, and everybody else who is in the secret, have been expecting you for the last month.” Once he had arrived in London, Henry was accommodated in grand style. Overnight, the lows of “Mezzo Cammin” soared to intoxicating highs. “I write this from Dickens’ study, the focus from which so many luminous things have radiated,” he informed Sumner. “The raven croaks from the garden; and the ceaseless roar of London fills my ears. Of course, I have no time for a letter, as I must run up in a few minutes to dress for dinner.”

It was nonstop for two weeks, elegant dinners, concerts, plays, “Shakespeare on the stage as never he was seen before.” There were drinks with the book illustrator George Cruikshank and the portrait painter Daniel Maclise, and an après-play get-together with the actor William Macready at Drury Lane following his performance in As You Like It. Dickens graciously presented copies of Ballads and Other Poems to his friends; and just as Henry had shown him the Boston waterfront, Dickens worked in a few side trips of his own, one to see “the tramps and thieves” of the London slums, “the worst haunts of the most dangerous classes.”

Henry’s mornings were not passed idly, either, not with the Savile Row fashion district nearby, and the opportunity to be fitted for some stylish English clothes and shoes. “McDowall, the boot maker, Beale the Hosier, Laffin the Trousers Maker, and Blackmore the Coat Cutter, have all been at the point of death, but have slowly recovered,” Dickens teased in a letter posted a few weeks after Henry’s departure. “The medical gentlemen agreed that it was exhaustion, occasioned by early rising—to wait upon you, at those unholy hours.” In the little down time he did have, Henry read American Notes, which Dickens had given him on arrival. “I have read Dickens’ book,” he informed Sumner of the new release. “It is jovial and good natured,” though at times “very severe,” a subtle alert to what would be received by many in the United States as a rebuke of the dark underbelly of American culture. “You will read it with delight and, for the most part, approbation. He has a grand chapter on Slavery.”

During a turbulent voyage home, Henry responded to the pleas of his friends. “The great waves struck and broke with voices of thunder,” he wrote Freiligrath after his return. “In the next room to mine, a man died. I was afraid they might throw me overboard instead of him in the night; but they did not. Well, thus ‘cribbed, cabined and confined,’ I passed fifteen days. During this time I wrote seven poems on Slavery. I meditated upon them in the stormy, sleepless nights, and wrote them down with a pencil in the morning. A small window in the side of the vessel admitted light into my berth; and there I lay on my back, and soothed my soul with songs.”

Issued by the Cambridge publisher John Owen, Poems on Slavery did not attack slave owners directly, focusing instead on the lives of African Americans, portraying them with broad, sentimental strokes. Nowhere did he minimize the humiliations they endured, nor did he downplay in any way the immorality of human bondage. In “The Slave in the Dismal Swamp,” a “hunted Negro” on the run, “infirm and lame” from repeated beatings, lies “crouched in the rank and tangled grass” like “a wild beast in his lair,” the sound of a “horse’s tramp” in pursuit and a “bloodhound’s distant bay” filling the air. A central image in “The Slave’s Dream” is the “driver’s whip” that maintains order among the oppressed; taking the form of a ballad, “The Quadroon Girl” tells of a beautiful young woman on an island paradise, presumably in the Caribbean, who is sold for “glittering gold” as chattel to a passing ship captain, her fate to be his “slave and paramour in a strange and distant land.” The most poignant of the seven poems, “The Witnesses,” describes a sunken ship “half buried in the sands” in which “lie skeletons in chains,” with “shackled feet and hands”:

These are bones of Slaves;

They gleam from the abyss;

They cry, from yawning waves,

“We are the Witnesses!”

Because the poems avoided expressing outright condemnation and outrage, they were judged too tame in some quarters. Margaret Fuller called them “the thinnest of all Mr. Longfellow’s thin poems; spirited and polished like its forerunners; but the topic would warrant a deeper tone.” Henry himself would describe the verses as being “so mild that even a Slaveholder might read them without losing his appetite for breakfast.” They were deemed provocative enough, however, that the Philadelphia publisher Carey & Hart excluded them from an edition of Henry’s collected works. Nathaniel Hawthorne, for his part, was stunned. “I was never more surprised than at your writing poems about slavery,” he allowed. “You have never poetized a practical project hitherto.” John Greenleaf Whittier was sufficiently impressed that he urged Henry to run for Congress under the aegis of the Liberty Party, an abolitionist group he had helped found. “Though a strong anti-Slavery man, I am not a member of any society, and fight under no single banner,” Henry replied, unequivocal in his determination to remain out of the crossfire. “Partisan warfare becomes too violent, too vindictive for my taste, and I should be found but a weak and unworthy champion in public debate.”

And he never wavered. “I am glad I am not a politician, nor filled with the rancor that politics engenders,” he wrote in his diary. Asked by a New York activist in 1852 for a few lines of commentary for the cause, he declined again: “I think no one who cares about the matter will be at any loss to discover my opinion on that subject.” Many years later, Henry’s son Ernest would write that his father “hated excess or extremes” of all sorts, and “believed in the juste milieu”—the happy medium—in everything. “He was not a rushing river, boiling and tumbling over rocks, but the placid stream flowing through quiet meadows. He hated war, he hated violence in any form, and though nothing roused his indignation like injustice, he was for peaceful measures if possible.”

HENRY’S JOURNAL IS quiet during the early weeks of 1843, suggesting a sense of calm that is reinforced by his letters, which show at long last acceptance of Fanny Appleton’s aloofness. “My Etna is burnt out,” he conceded to Sam Ward of his expired hopes, “my Boundary Line is settled. Impassible Highlands divide the waters running North and South. ‘Let the dead Past bury its dead’ and excuse me for quoting myself”—but quote “A Psalm of Life” he did, and that, it would appear, was that. Then, in early April, he was invited by the Nortons to a party for Tom Appleton, who was departing yet again for Europe. A few years earlier, Fanny’s sister, Mary, had married Robert Mackintosh, the son of an English diplomat, and moved to London; her father, meanwhile, had taken a second wife, Harriot Coffin Sumner, who in quick succession bore him three children—William Sumner Appleton (1840–1903), Harriet Sumner Appleton (1841–1923), and Nathan Appleton Jr. (1843–1906)—and assumed all domestic responsibilities at 39 Beacon Street. Now, Tom was off for the other side of the Atlantic.

How Henry and Fanny found themselves alone in a quiet alcove for a little tête-à-tête—it was the doing, in all likelihood, of their mutual friend Catherine Eliot Norton—is anyone’s guess. But speak they did, openly and candidly, for the first time in years, including some discussion of Hyperion, apparently to Fanny’s satisfaction, given what came next. “You must come and comfort me, Mr. Longfellow,” she said, allowing how lonely she was going to be in the weeks ahead. Henry might just as likely have been struck by a meteorite. He would write on April 13, 1844—the first anniversary of their rapprochement—that “the day and evening shall be kept as a holiday and be blessed for evermore.” Quoting Dante, he declared it the miraculous arrival of a Vita Nuova—a new life—of happiness, which he would repeat again and again on that date in the years that followed.