14

Pericles and Aspasia

A delightful stroll with Fanny on the cliff, watching the sails in sunshine and in shadow, and our own shadows on far-off brown rocks. This is our last evening walk at Nahant, and it is gone like the sails and the shadows.

—Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s journal, August 28, 1850

The sea was glorious this morning; after a long tranquility it was all alive again and full of its noblest energy—renewing all my old passion for its vigorous freshness and beauty.

—Fanny Longfellow, letter to Emmeline Austin, July 28, 1851

You can not escape the ocean here. It is in your eye and in your ear forever. At Newport the ocean is a luxury. You live away from it and drive to it as you drive to the lake at Saratoga, and in the silence of midnight as you withdraw from the polking parlor, you hear it calling across the solitary fields, wailing over your life and wondering at it. At Nahant the sea is supreme. The place is so small that you can not build your house out of sight of the ocean, and to watch the splendid play of its life, is satisfaction and enjoyment enough. Many of the cottages are built directly on the rocks of the shore.

—George William Curtis, “Nahant,” in Lotus-Eating (1852)

For those who could afford the luxury of getting away, the arrival of summer around Boston and Cambridge usually meant packing the family up and heading off for cooler climes, the sea breezes of Nahant and Newport being traditional favorites, the crisp mountain air of the Berkshires another. Henry and Fanny found respite in each of these elite enclaves during the years of their marriage, often inviting selected friends to join them for varying periods of time. For their 1850 and 1851 holidays, they rented a “low, long house in the village” of Nahant, a craggy slip of a town on the northern rim of Massachusetts Bay, and for much of the nineteenth century the warm-weather retreat of choice for a mix of the city’s movers and shakers and top educators from Harvard, who had established a cozy little coven there of their own; Fanny once described its clannish ambiance as “Boston in summer clothes.” In a feature article for the New-York Daily Tribune, George William Curtis expanded on the favor it enjoyed: “No city has an ocean-gallery, so near, so convenient and rapid of access, so complete and satisfactory in characteristics of the sea, as Boston in Nahant.”

When Curtis (1824–92) offered that homage to the tony seaside haven, he was on the fast track to becoming a writer of consequence, his polished manner and sunny disposition giving him entree to circles that mattered in mid-nineteenth-century America. Born in Rhode Island and privately tutored in Boston and Providence, Curtis moved to New York with his family as a teenager. Between 1844 and 1845, he spent eighteen months at Brook Farm, the experimental community in West Roxbury, Massachusetts, and after that on a communal farm in Concord, establishing meaningful relationships with George Ripley, Nathaniel Hawthorne, Charles Anderson Dana, Margaret Fuller, Theodore Parker, and Ralph Waldo Emerson.

In 1846, Curtis embarked on four years of foreign travel that took him through much of Europe, Egypt, and Syria, all the while keeping a journal and writing occasional dispatches for the Morning Courier and New-York Enquirer. A book drawn on those experiences, Nile Notes of a Howadji, appeared in 1851, followed the next year by The Howadji in Syria, giving him widespread recognition at an early age, and a catchy nickname. Derived from a Turkish word for “merchant,” howadji, as Curtis applied it, was “the universal name for a traveler.” In the years that followed, he worked as a critic and feature writer for the New-York Daily Tribune, an editor for Putnam’s Monthly Magazine, and a columnist for Harper’s New Monthly Magazine and Harper’s Weekly, where he became editor in 1863. He also made a name for himself as an orator championing the causes of abolition and women’s suffrage, and was a founder of the Republican Party. Over four decades of professional writing, he wrote newspaper articles on many topics, and several other books, including a novel. Not long after meeting Henry and Fanny, he produced a series of travel essays for the Tribune, including his take on Nahant, later published in Lotus-Eating: A Summer Book.

Henry’s first mention of the Howadji appears on March 22, 1851, when he and Fanny gave a dinner for Charles Eliot Norton and a friend of his—George Curtis of New York—whom he had met in Paris. “They are just returned from Eastern travel, and their talk is of the Sphinx and the Pyramids. Mr. Curtis is the author of Nile Notes of a Howadj; a rhapsody on Egypt, I imagine by a few extracts I have seen. A very pleasant, amiable young man, of the Emerson school I should say.” Two days after that, Henry and Fanny attended a “very nice supper” for Curtis hosted by Andrews Norton, the father of Charles, at his Shady Hill home. The cuisine was Italian, Henry noted approvingly, “the whole illuminated with a huge straw-covered flask of Chianti wine,” and the conversation so congenial, “we sat till nearly one o’clock.”

In his next visit to Craigie House, Curtis gave Fanny a copy of his Nile Notes, which “we begin to read with much delight,” Henry recorded—“we” being code for their favorite pastime, she reading aloud each night to him. “It is the poetry of the Nile and a very remarkable book.” Henry offhandedly mentioned in the next entry that he was putting the finishing touches on The Golden Legend, having just read the entire draft to Charles Sumner, which his friend had deemed “very learned and original!” Henry nonetheless decided to rewrite the first scene, “putting the blank verse into rhyme. It makes it less ponderous; for blank verse—at least my blank verse—seems to me very heavy and slow.”

A week after receiving Nile Notes, Fanny informed Sam Longfellow how much she and Henry had enjoyed such “a very summery book,” one so “full of glowing Tennysonian pictures.” She identified the author as “an amiable youth named Curtis” they had recently met, and offered similar praise that same day to Tom Appleton, adding that the book’s “soft Lydian airs” had “lulled” her and Henry into forgetting “the harshness of this land of storms and mental conflicts.” Curtis achieved this, she added, by “deliciously” creating a “languid atmosphere” notable for its “many sly touches” of humor. “It is very soothing to the nerves so I recommend it as a gentle medicine—even tho’ it be to you of poppies. He said to me ‘It is a very young book’—but that is why I like it,—for I love that golden shore from which I feel sliding away, as I dare say you do today. But we are among those favored few who can always row back to it for an hour’s stroll, when we like, however strong the current sets down stream.”

A few months later, the Longfellows were on Nahant, with just 1.2 square miles of land area the tiniest municipality in all of New England. The name is derived from a Native American word meaning “almost an island,” a perfect description for what in essence is a narrow peninsular projecting from the city of Lynn in Essex County southward into Massachusetts Bay, the two connected by a narrow causeway and forming the eastern flank of Lynn Harbor on the North Shore. Early in their stay, Fanny wrote her cousin Isaac Appleton Jewett, then in Europe, that they were still wanting for stimulating company. “We take long walks, and read quiet, meditative books, and see many tolerably pleasant people. But I confess I do hunger and thirst, occasionally, for more literary people, or rather thoughtful, earnest people—so many are shallow and occupied by trifles. There is so little real, rich cultivation here, good, deep soil, and again I envy you some of your English acquaintances.” That ennui would soon be relieved by the arrival of Curtis, who spent a good deal of time in their company over the next several weeks.

For their 1852 vacation, they rented a “spacious” house in Newport, Rhode Island, “delightfully situated on the clover-scented cliffs with nothing but turf between us and the sea and a most extensive view of the latter from our windows,” as Fanny described the “cottage” for her sister-in-law Anne in Maine. They found everything “in fresh order” when they arrived, and best of all, it was “filled with a few very agreeable friends of ours.” Not arrived yet, but expected presently, was “the Howadji Mr Curtis,” leaving them still with “two rooms besides desiring occupants which complete our number.” Before the summer was out, Samuel Gridley Howe and Julia Ward Howe would join the party—the seasonal rate was eighteen dollars per room per week—making for a “very merry” holiday retreat.

Daguerreotype taken during summer sojourn in Newport, 1852. Henry stands at right with the top hat, next to Julia Ward Howe and Tom Appleton. Fanny is seated in the middle between two friends, John G. Cosler and Horatia Freeman.

On their first day in Newport, before they had so much as settled into their quarters, “a singular damsel” had appeared unannounced, “shrouded in a white veil and saying, ‘I am the Sybil,’ ” as Fanny would later relate the incident. Henry had no earthly idea who the woman was; the veiled figure thereupon identified herself as one Faustina Hasse Hodges, an organist and composer who had written several letters to Henry “on musical matters,” six of which are in the Houghton collections. Fanny described her as “a romantic beauty” with a “decided talent, if not genius” as a composer, and a musician “who plays with wonderful brilliancy,” her curious behavior notwithstanding. “Such strange damsels there are in this country,” she concluded with characteristic aplomb, “and such odd things they do.”

Bizarre as the incident may have been, it underscores the impact Henry’s work was beginning to have throughout American culture, and how it was finding fruitful voice away from the printed page. Among the materials maintained in the Longfellow House archives are several hundred examples of original sheet music, many of them beautifully lithographed, a number inscribed to Henry by the composers, all adapting a poem or verse from Henry’s oeuvre. I was able to document five of his poems that Hodges adapted for musical adaptation. Henry made no mention of the Newport encounter in his journal, concentrating instead on the good company of his wife and guests.

“We went and sat by the sea under the cliff,” he wrote of one afternoon walk, “and watched the breakers and the sails, and thought the rocks looked like the Mediterranean shore, and that the Italian language would sound well. Here in truth, the sea speaks Italian; at Nahant it speaks Norse.” During an unaccompanied stroll into town a few days after that, he paused by “a shady nook, at the corner of two dusty, frequented streets,” his attention diverted by an “iron fence and a granite gateway” that led to an enclosed burial ground next to an inactive synagogue. Escorted inside by “a polite old gentleman who keeps the key,” he came upon a cluster of old graves, nearly all of them “low tombstones of marble, with Hebrew inscriptions, and a few words added in English or Portuguese.” Drawing on this unusual encounter with the past, he would later write “The Jewish Cemetery at Newport,” a poem that commemorates the small community of Sephardic Jews that had moved fitfully from place to place after being forced out of Spain and Portugal in the fifteenth century by the Inquisition, finding sanctuary finally in 1658 in Rhode Island, which fourteen years earlier had granted freedom of worship to all religious sects.

Henry and Fanny did some sightseeing, too, visiting landmarks associated with the late William Ellery Channing, a native of Newport, and also Whitehall, the country farm where Bishop George Berkeley, the Anglo-Irish philosopher, wrote the book Alciphron in the early 1700s. But their most agreeable moments were spent with their companions, front and center among them Curtis, who by now had become friendly with the entire family. Ernest Longfellow, the couple’s second-born child, would remember Curtis for his “great charm of manner,” a “most musical voice,” and a “sweet disposition,” altogether “one of the most delightful of men” to ever visit their home. Alice Longfellow described him as one of their “most radiant and delightful” houseguests, “so handsome, and gracious, and kind” to the children. “He was much given to falling in love, though we did not know that, and thought he quite belonged to us.”

Once returned to Craigie Castle that fall, Fanny savored “the acquaintanceships and friendships” that had deepened in Newport, hoping they would not be “as evanescent as the summer” weather they had all enjoyed so thoroughly. “I cherish an especial interest in the Howadji, and his beautiful and loveable disposition has won much upon both of us,” she told Tom Appleton. “He deserves the best of fortunes and I trust will secure it, for few could resist such a combination of good looks, talent, and goodness of heart.”

The aspiring Boston poet William Winter was introduced to Curtis at Craigie House when both were young men just embarking on their careers. Winter described Curtis as being “lithe, slender, faultlessly appareled, very handsome,” rising at his approach, and “turning upon me a countenance that beamed with kindness, and a smile that was a welcome from the heart.” Curtis had the manner “of a natural aristocrat—a manner that is born, not made; a manner that is never found except in persons who are self-centered without being selfish; who are intrinsically noble, simple, and true.” Of his oratorical skills, Winter wrote that Curtis spoke in “a level tone,” always “without a manuscript” in front of him; whether his speech was long or short, “he never missed a word nor made an error.”

Curtis became friends with the Longfellows at a time when Henry was a dominant force in American letters, with many triumphs yet to come. His enthusiasm for Henry’s work was unqualified, and as a trusted insider, he had direct access to the entire family. Of equal weight was the esteem Curtis had for Fanny, going so far as to suggest—in print—that she was a modern version of Aspasia of Miletus, a legendary intellectual from ancient times who drew praise from such figures as Socrates, Anaxagoras, and Phidias, along with the undying love of Pericles, hailed by Thucydides during the Golden Age as the “first citizen of Athens.” As towering female figures from antiquity go, Aspasia was not a queen, like Helen of Troy, Cleopatra of Egypt, or Zenobia of Palmyra; she was not even allowed Athenian citizenship by virtue of her Milesian bloodlines, and for that reason unable to marry Pericles. Instead, her stature and influence came through words—her expertise as a master rhetorician and philosopher, memorialized in the writings of Plato, Sophocles, Xenophon, Cicero, and Athenaeus; the best-known biographical treatment of her is to be found in Plutarch’s Lives of the Noble Greeks and Romans, written around AD 100.

George William Curtis, 1854, by Samuel Laurence

In her personal life, Aspasia bore Pericles a son, also named Pericles, and advised him on many matters. It was asserted by some that she composed the great funeral oration Pericles delivered during the Peloponnesian War. An academy she established in Athens for young women became a chic salon for influential men. “Socrates himself would sometimes go to visit her, and some of his acquaintances with him,” Plutarch wrote, “and those who frequented her company would carry their wives with them to listen to her.” In Menexenus, one of the Socratic dialogues, Plato has Socrates deliver a speech he claims to have learned from Aspasia. In his Memorabilia, Xenophon has Socrates quote Aspasia directly on a number of matters; Athenaeus suggested that it was Aspasia who taught Socrates rhetoric.

For Curtis to imply that Fanny was a kind of Aspasia to Henry’s Pericles, then, is bold by any yardstick, leaving open, however slightly, the inference that she was more than muse to Henry: she was perhaps, at least in his eyes, an essential nutrient to his creative impulse. Based on a number of findings—praise be for paper trails—I can assert with confidence that for a period she was certainly all of that for Curtis. The first reference he made to Aspasia came in his 1851 Tribune essay about Nahant, which was reprinted the following year in Lotus-Eating, a collection of travel pieces in which he ranked northeastern summer resorts for people of a certain stature, or what William Dean Howells called “fashionable life at American watering-places.” The hardcover edition featured illustrations by John Frederick Kensett, a talented artist of the Hudson River School, who would become an art instructor for Fanny and Henry’s son Ernest. Here is the pertinent segment:

At Nahant you cannot fancy poverty or labor. Their appearance is elided from the landscape. Taking the tone of your reverie from the peaceful little Temple and glancing over the simple little houses, with the happy carelessness of order in their distribution, and the entire absence of smoke, dust, or din, you must needs dream that Pericles and Aspasia have withdrawn from the capitol, with a choice court of friends and lovers, to pass a month of Grecian gaiety upon the sea. The long day swims by nor disturbs that dream. If haply upon the cliffs at sunset, straying by “the loud sounding sea,” you catch glimpses of a figure, whose lofty loveliness would have inspired a sweeter and statelier tone in that old verse, you feel only that you have seen Aspasia, and Aspasia as the imagination beholds her, and are not surprised; or a head wreathed with folds of black splendor varies that pure Greek rhythm with a Spanish strain,—or cordial Saxon smiles and ringing laughter dissolve your Grecian dream into a western reality.

A fair question to ask is whether there is any supporting evidence to show that Curtis was anointing Henry and Fanny the Pericles and Aspasia of their generation. The first confirmation that he was doing exactly that comes from Fanny herself in a letter to Emmeline. “Do you ever see the New York Tribune?” she asked. “In one paper of this month is a very nice account of Nahant by Howadji Curtis, and in a later one of Newport. There was also a very good one about Lake George discriminating very well the difference of our scenery and the European.” She then added that “his Mot Notelpa,” a character quoted in two instances, “is Tom,” her brother, and that “I am complimented under the name of Aspasia (a dubious compliment!) in the Nahant one.”

The “dubious” misgiving was undoubtedly made mindful of the many vicious attacks made on Aspasia’s character by the political enemies of Pericles, including unfounded allegations that she was nothing more than a clever, conniving, opportunistic courtesan, perhaps a high-end prostitute. Aristophanes even claimed in The Acharnians (425 BC), his earliest surviving play, that she was responsible for instigating the Peloponnesian War. While obscure today, Aspasia was well-known in nineteenth-century literary circles, certainly by Henry and Fanny, who were both schooled in the classics. There is, in addition, a copy of Walter Savage Landor’s popular epistolary novel of 1839, Pericles and Aspasia, in the Craigie House library, bearing Henry’s personal bookplate. Present there as well are comprehensive histories of ancient Greece by Oliver Goldsmith, William Mitford, and William Smith, and if we know anything at all about the Longfellows, it is that they read their books.

Curtis gave many of his real-life characters fictitious nicknames. The one he used in The Homes of American Authors for Tom Appleton—Mot Notelpa—is an anagram of his name, with a single “p.” He referred to Nathaniel Hawthorne as “Monsieur Aubépine,” a play on the French word for the shrub hawthorn, and a sobriquet Hawthorne himself used for the mock preface to the story “Rappaccini’s Daughter.” The one he gave to Bronson Alcott—Plato Skimpole—was suggested to him by Fanny, and used in a way that leaves no doubt that she was his Aspasia. Confirmation comes in a letter Fanny wrote to Tom Appleton announcing that Homes had just appeared, “with capital sketches of the various mansions and beautifully written essays upon them and their owners by various hands. The ‘Howadji’ has done ours and Emerson’s and Hawthorne’s with his usual grace and humor, wickedly fastening upon poor Alcott the name I gave him of Plato Skimpole.”

The phrase to be underscored here is “the name I gave him” for Bronson Alcott, a figure in the Emerson circle known for having established the alternative Temple School in Boston (1834–41), and for dispensing his philosophical maxims in “Orphic Sayings,” a series of prosaic aphorisms for The Dial magazine. Fanny had conveyed her negative opinion of Alcott’s pithy pronouncements to Emmeline a decade earlier when discussing the general merits of the periodical, which for the four years of its initial existence (1840–44) was an organ of the transcendentalist movement. “There is much readable in the Dial,” she allowed, but felt there was also plenty of “nonsense,” too, and if her friend had by chance “stumbled on” Alcott’s “Orphic Sayings,” she would have noticed a “shallowness of absurdity this age must have lived to reach.” Fanny was by no means alone in her assessment; The Knickerbocker published a parody called “Gastric Sayings,” and The Boston Post compared the maxims to a “train of fifteen railroad cars with one passenger.”

In his essay, Curtis identified Alcott as the “Orphic Alcott—or Plato Skimpole, as Aspasia called him,” and repeated the derisive nickname three more times. The key phrase there, needless to say, is “as Aspasia called him.” The “Plato” part of the coinage was a sarcastic reference to Alcott’s orphic deliberations; “Skimpole” likened him to Harold Skimpole, a bumbling character in Bleak House, the Charles Dickens novel then causing a minor sensation in the English-speaking world, and widely assumed to be an unflattering caricature of the British critic Leigh Hunt.

As a reference to Alcott, the sobriquet caught on, and appeared in print occasionally in the years that followed, usually framed as “the name George Curtis called Alcott.” There is an amusing footnote to this, one I would never have found without benefit of a shot-in-the-dark Google search using “Plato Skimpole,” “Alcott,” and “Curtis” as my key words. Among the items that turned up was a letter to The New York Times Saturday Review of Books in 1898. The writer of the letter, identified only by the initials E. L. C., called into question an assertion made in what was then a newly published volume of Curtis’s letters to the effect that “Plato Skimpole was Margaret Fuller’s name for Alcott.” That was highly unlikely, the letter writer continued, since Margaret Fuller had drowned at sea off Fire Island in 1850, a full two years before Bleak House was published, meaning that she had been given credit “for someone else’s witticism.”

A week later, three other readers weighed in, filling most of an entire column in the newspaper. The first wrote to clarify a point—it was not Curtis who attributed “Plato Skimpole” to Margaret Fuller, it was the person who had edited the posthumously released letters. “I should doubt very much whether any one but Curtis was responsible for the nickname.” The next letter writer went to the original source and referred directly to Homes of American Authors, and quoted Curtis verbatim, where “Aspasia” is identified as the source, leading to a single question in the headline: “Now Who Was This Aspasia?” With all the principals long since deceased, and nobody around to come forward and clear the air, the matter has remained unresolved for more than a century—until now.

In 1853, Curtis was named editor of Putnam’s Weekly. The following year he spent a fortnight at Craigie House gathering information for his Homes of American Authors essay. Fanny had hoped to make Curtis “acquainted more with Boston” during that June stay, but inclement weather kept them anchored to Craigie House. She was able to arrange “a small musical party” for him, which featured the vocals of a lovely young woman from Boston, delivered in “the purest Italian style,” her “magnificent voice” so “powerful and rich” that her performance “woke all the children, but they were luckily quiet.” Curtis was so “enchanted” with the woman he went into Boston by himself the next day “bearing a fresh bouquet of roses from our garden. She is a very pretty girl besides, with much quiet self-possession.”

The following Sunday, Henry took a carriage drive with his wife and their houseguest to nearby Waltham. “A feeling of the country, with fresh odors of fields and woods and the sight of great gray barns. After dinner drove Curtis into the Old Colony Railway, and so departed another friend whom we prize and love much. A very gentle, joyous spirit, with a sharp eye for the weakness of humanity and great pity and compassion for them likewise.” Among Curtis’s colleagues at Putnam’s was one Charles F. Briggs, with whom he corresponded often while away on writing assignments. During this extended stay at Craigie House, he drafted a letter to Briggs that begins with an extraordinary paragraph that speaks for itself in the context of this chapter: “I am staying now with the poet and his wife. What though it rains, or shines? It is quite the same to me. I sit and look over the melancholy meadows at the winding Charles, and quote my host, or, which is better, I contemplate my hostess, and thank God for the gracious and beautiful woman for whom, clearly, the woods, flowers, the stars, sun, and men were created.”

Two months later, at the height of summer, Catharine Maria Sedgwick, Fanny’s “dear Aunt Kitty” of previous years, sent a cordial letter of reference to Henry on behalf of a visitor, requesting “a kind reception” when he came calling. “I hope you and dear Fanny are enjoying these summer months as they pass,” she continued, switching subjects deftly. “The season, even from the first of May, has verified all the poets have sung of it. Have you both forgotten the lovely hill-side by the Housatonic?” Sedgwick concluded by noting she had at that moment a mutual acquaintance in her house—there, we can presume, doing an interview for an essay, possibly the one about her in Homes of American Authors: “Your friend and your wife’s admirer (what conjugal strength when both can be united!) is at this moment singing mellifluously in our little parlor and I think the song’s prosperity lies in the ears that listen to him.” Sedgwick moved on to her closing goodbye, then added a postscript to identify the visitor: “I have omitted George Curtis’ name. Perhaps you could have guessed it.”

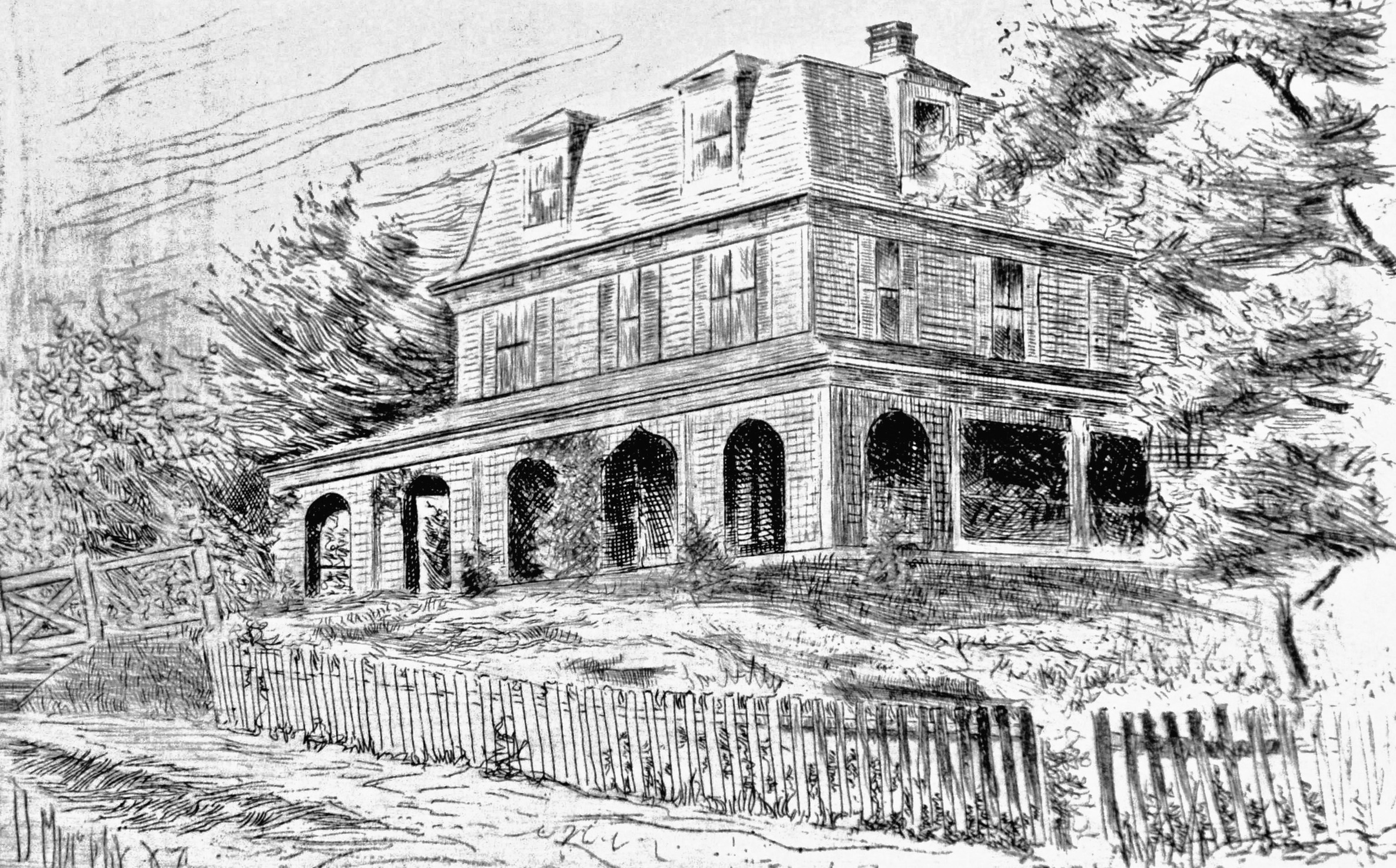

Drawing of the Longfellow cottage on Nahant, from the Longfellow print collection. The house was destroyed by fire in 1909; only the stone foundation remains on the site.

What Sedgwick meant by that comment—“what conjugal strength when both can be united!”—is open to interpretation. I believe “Aunt Kitty’s” conversation with Curtis—who like her was a professional writer—had involved a bit of shoptalk, and what they agreed is possible when two people they both knew well pursue a common goal. Fanny, to be clear, was the first person to insist that Henry was the poet in the family, going back to the first weeks of their marriage, when she was urging him to write “The Arsenal at Springfield,” and vision problems had occasioned a temporary slowdown in his writing. “Now that the vein is again opened,” she informed George Washington Greene, “I hope much will flow from it and if his Pegasus needs a spur, I can answer for it being duly applied, as I feel guilty, in a measure, for his sluggish pace of late.” She used a similar image with her mother-in-law: “I am a pretty active spur upon his Pegasus, and wish it were possible for a poet, in this age of the world, to surrender himself wholly to his vocation.”

To her closest friends and relatives, Fanny mentioned works in progress with the authority of someone who was directly involved in the process, her “our book” collaboration being just one example. A few others from her correspondence illustrate the point.

“I suppose I can now tell you that he is correcting the proofs of a long poem called Evangeline written in hexameter,” she informed Emmeline. “It is a very beautiful touching poem I think and the measure gains upon the ear wonderfully. It enables greater richness of expression than any other, and is sonorous like the sea which is ever sounding in Evangeline’s ears.” To Sam Longfellow, she previewed The Song of Hiawatha: “I hope you will like it. It is very fresh and fragrant of the woods and genuine Indian life, but its rhyme-less rhythm will puzzle the critics, and I suppose it will be abundantly abused.” A self-effacing comment Fanny made to one of Henry’s sisters in 1858 during composition of The Courtship of Miles Standish not only claimed direct involvement, but asserted further that they collaborated on a regular basis. “Henry has been writing a poem of some length, and we sit in the summer-house and correct proof and discuss this line and that these sunny days. I am ashamed to say that he always takes my suggestions, which may not improve the poem!”

If there is one overriding criticism that applies to Henry’s journals, it is that he tells us very little about his creative process—which had he done so would go a long way to explain exactly how he worked with his wife. One entry, written when he was about to commit himself totally to the writing of poetry, offers some insight. “How brief this chronicle is, even on my outward life. And of my inner life, not a word. If one were only sure that one’s journal would never be seen by anyone, and never get into print, how different the case would be! But death picks the locks of all portfolios, and throws the contents into the street for the public to scramble for.”

Seventy letters Curtis wrote to Henry are in the Harvard collections, the first written around the time they met in 1852, the last in 1880, a year and a half before Henry died. They are uniformly respectful, cheery, and friendly, many written to coordinate visits, all of them while Fanny was alive extending “love,” “affection,” or “kindest regards” to Mrs. Longfellow and the children. There are no letters from Curtis to Fanny in the Houghton Library, but there are two in Longfellow House, one of them, dated November 5, 1854, announcing his engagement to Anna Shaw, the daughter of the Boston abolitionists Francis and Sarah Blake Shaw, and sister of Robert Gould Shaw, who would gain fame as commander of the Fifty-Fourth Massachusetts Regiment, the first all-black unit from the Northeast to see combat in the Civil War.

“My dear Mrs. Longfellow,” Curtis began, “I don’t know that you will be glad to hear of my engagement to Anna S. but I do know that you will be glad that I think myself happy.” The next two pages assured Fanny that he was happy with his choice, judging Anna to be “inexpressibly lovely and dear” to him. “I have not forgotten some little things you said to me, and I have profited from them. Therefore you may believe how sure I am, that at last, when you know her, you will say as I say all the time in my heart, ‘for she is as inimitable to all women as she is inaccessible to all men.’ She is not to be easily known.” Curtis closed with a single request: “It seems to me only too good. It makes me very humble and very proud to know how much she loves me. Good bye. Give my love to Mr. Longfellow—and give me your blessing.” Curtis and Anna were married a year later, and took up residence on Staten Island. “A generous box of wedding-cake” announced the wedding, Fanny informed Tom, which took place the day before Thanksgiving. “I sent Curtis a bronze ink stand with an ibis on it to remind him of his Howadji days, while the sober metal recalls the graver duties of the present.”

There is one more episode in the matter of George William Curtis and his friendship with the Longfellows to be discussed here. Once again, we must be mindful that so much of what is expressed on paper at this time is implied, not directly stated. The Harvard historian and chronicler of nineteenth-century American culture Lawrence Buell characterized this Victorian conceit for me as “the tacitness of the period,” the tendency to communicate in a fashion that would be “understood without being openly expressed,” a brief note Fanny wrote to Emmeline early in 1857 being a classic example. It was a cover letter, basically, for the gift of some pineapple jam from the Caribbean “which may possibly be agreeable to you,” courtesy of her sister and her brother-in-law Robert Mackintosh, who between 1850 and 1855 had served as governor general of Antigua and viceroy of the British colony of the Leeward Islands. Included in the package was a copy of Prue and I, a book written by George William Curtis and published the previous fall, “which, if you have not read, may help off an invalid hour.” It contains, she then added, “a subtle sweet fancy which I think you will like.” Nowhere in Fanny’s surviving correspondence do we find another mention of the book. The “subtle sweet fancy,” as she coyly put it to her dearest friend, is to be found on the dedication page:

TO MRS. HENRY W. LONGFELLOW,

In memory of the happy hours at our

Castles in Spain.

The inscribed copy Curtis presented to Fanny—in bibliographical parlance, the “dedication copy”—reads “Mrs. Longfellow from her aff., George Wm. Curtis,” and is dated November 12, 1856, a year and a day after he had informed her of his engagement, and two weeks to the day before his marriage. His “Howadji days,” as Fanny had put it in her letter to Tom Appleton, and as she had reminded Curtis with her wedding gift, were indeed in the past.

Not only did Curtis dedicate the book to Fanny, but a strong argument can also be made that he used her as a model for Prue, the character who inspires the unnamed narrator’s passion for flights of fancy. Written as a series of light sketches and meditations, Prue and I is narrated by an aging bookkeeper who contemplates places he has visited only in his imagination. His wanderings reach full flower in a chapter called “My Chateaux,” and—it should come as no big surprise—include stimulating visits to what they both call “castles in Spain.”

“A man must have Italy and Greece in his heart and mind, if he would ever see them with his eyes,” he explains in a prefatory note. “For my part, I do not believe that any man can see softer skies than I see in Prue’s eyes; nor hear sweeter music than I hear in Prue’s voice; nor find a more heaven-lighted temple than I know Prue’s mind to be. And when I wish to please myself with a lovely image of peace and contentment, I do not think of the plain of Sharon, nor of the valley of Enna, nor of Arcadia, nor of Claude’s pictures; but, feeling that the fairest fortune of my life is the right to be named with her, I whisper, gently, to myself, with a smile—for it seems as if my very heart smiled within me, when I think of her—‘Prue and I.’ ” A “subtle sweet fancy,” indeed, as Fanny described the book to her dearest friend.