SOON after the court’s ruling on May 17, 1954, Barbara Johns’s sister Joan and her parents left Virginia for a weekend visit with relatives in Washington, D.C. Joan’s younger brothers stayed with Grandma Croner. During the night, Joan’s family’s house went up in flames. Her uncle spotted the fire and wakened the Croners. But it was too late. The house burned down. When Joan and her parents returned, the house “was in ashes,” she said. “It was horrible. We were all just in tears.” Although the fire was investigated, “nothing came of it,” said Joan. “My parents weren’t too surprised.” They suspected the fire had been set because Joan and Barbara were plaintiffs in the case that was part of Brown.

Southerners blasted the court’s decision. Governor Thomas B. Stanley of Virginia urged citizens to remain calm. But the state’s Senator Harry Byrd said, “We are facing a crisis of the first magnitude.”

Governor James F. Byrnes of South Carolina said, “South Carolina will not now nor for some years to come mix white and colored children in our schools.”

Governor Herman Talmadge of Georgia exclaimed, “I do not believe in Negroes and whites, associating with each other either socially or in school systems, and as long as I am governor, it won’t happen.”

Black communities cheered the landmark decision. Robert Johnson, a history professor at Virginia Union University said, “This is a most exciting moment. A lot of us haven’t been breathing for the past nine months. . . . Today the students reacted as if a heavy burden had been lifted from their shoulders. They see a new world opening up for them and those that follow them.”

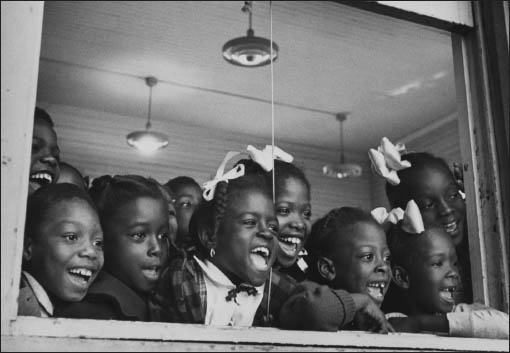

Happy students in New Orleans, Louisiana. 1954

Sara Lightfoot, who grew up to be a writer, sociologist and professor of education at Harvard, was ten when she heard the news. “Jubilation, optimism and hope filled my home,” she wrote. “And for the first time I saw tears in my father’s eyes.” He said to Sara, “This is a great and important day.”

Harlem’s Amsterdam News reported, “The Supreme Court decision is the greatest victory for the Negro people since the Emancipation Proclamation.”

In North Carolina, teenager Julius Chambers, who later became a director for the Fund, gathered his classmates and teachers to celebrate. “We assumed that Brown was self-executing,” he said. “The law had been announced and people would have to obey it. Wasn’t that how things worked in America, even in White America?”

But on June 25, Governor Stanley announced, “I shall use every legal means at my command to continue segregated schools in Virginia.”

Marshall told reporters that if any state didn’t obey the ruling, the NAACP would gladly take them back to court. “If they try it in the morning, we’ll have them in court the next morning—or possibly that same afternoon.”

“I’m in a hurry,” he declared. “I want to put myself out of business. I want to get things to a point where there won’t be an NAACP—just a National Association for the Advancement of People.”

In June, at the NAACP’s forty-fifth annual convention, Marshall told the crowd that schools should be desegregated “in no event, later than September of 1955.”

During the summer some Southern communities began desegregating their schools. That fall in Baltimore, Maryland, nearly 3,000 black students were going to schools that had been all-white. The progress reports encouraged Marshall and his team.

Myrtha Trotter at Claymont High School, Claymont, Delaware. May 31, 1954

In August, lawyer Lou Redding coached eleven black students as they prepared to enter Milford High School in lower Delaware. “We were not smart enough to be afraid,” recalled Orlando Camp, one of the students. “We felt it wouldn’t be a big deal. We played with white kids in the summertime and we didn’t feel intimidated.”

Orlando had graduated from an all-black elementary school where they used books mimeographed from twenty-year-old books that were scribbled with pencil notes. “Getting an education in an all-white school would give us greater opportunities,” he said. “My mother gave me one hundred and fifty dollars to get new clothes. This was a significant amount of money indeed for a poor black family. She was really happy.”

“On the first day everything was calm,” he remembered. There were three homerooms and the black students were split up. “The teachers were courteous but not friendly.” His biggest shock came when he opened the class’s textbook: Algebra II! Orlando had never taken algebra before, and he needed tutoring to catch up.

That day, white kids went home and told their parents about their new black classmates. Phones began to ring. The next day, crowds gathered as Orlando and the other black students went to school. By the third day, a mob of two thousand angry white parents stood outside Milford High and called the black children names. They smashed lightbulbs on the street, making sounds like gunshots. Local police refused to protect the black students, so the state police drove the kids to school. Photographers and reporters showed up and dubbed the black students the Milford Eleven.

African American parents and children in Baltimore, Maryland, stand across the street from School No. 34 as white picketers march, nearly a month after classes had started with white and black pupils mingling peacefully. September 30, 1954

At that point a racist named Bryant Bowles, president of the National Association for the Advancement of White People, arrived in Milford from Baltimore and incited a near riot. He rallied to raise money for opposing integration. More than eight hundred white people signed a petition against desegregation, and the superintendent closed Milford High. After a cooling-off period, the state board of education ordered the school to be reopened. A new school board expelled Orlando and his ten schoolmates. Redding and Greenberg drew up a complaint and won a court order that the Milford Eleven be readmitted.

“We stuck it out,” said Orlando. “We only had twenty-eight days in the white school. I wound up going to an all-black high school. But we made it possible for Milford to eventually integrate.”

Similar demonstrations sprang up throughout the country. Marshall and the Fund hired workers to advise the black community on how to go about seeking desegregation. Most black families wanted integration to begin as soon as possible.

Louis J. Redding (on the left) of Wilmington, Delaware, and Thurgood Marshall confer at the Supreme Court during a recess in the court’s hearing on racial integration in the public schools. April 1955

The Supreme Court had set late October as a date for hearing a final round of arguments about how to implement their ruling. Marshall and his team prepared briefs for Brown II. Robinson, who had argued the Virginia case, urged Marshall to demand an order for immediate desegregation. Why make black children wait any longer for a good education? Other members of the team recommended a gradual approach, giving school boards a chance to make the transition. Marshall decided to adopt this strategy. The final brief offered school districts up to two years to completely integrate.

The Court postponed the date for the hearing. Finally, on April 11, 1955, Marshall appeared before the Supreme Court to argue Brown II. His old opponent, John W. Davis, had died. New attorneys represented South Carolina and six other Southern states. Their briefs gave reasons for holding off integration: “withdrawal of white children from public schools, racial tensions, violence, loss of jobs for black teachers. Virginia argued that blacks scored far lower on IQ tests than whites,” recorded Greenberg.

S. Emory Rogers, speaking on behalf of Clarendon County, said that the court’s decision had presented his community with “terrific problems.” Local attitudes would have to change slowly. “I do not believe,” said Rogers, “that in a biracial society we can push the clock forward abruptly to 2015 or 2045. I do not think that . . . the white people of the district will send their children to the Negro schools.”

Attorney I. Beverly Lake, representing North Carolina, blamed the court for outlawing segregation. He said that if the court ordered immediate integration it would be “a death blow [to public education].”

Attorney General John Ben Sheppered of Texas said, “Texas loves its Negro people. It is our problem—let us solve it.”

On the fourth and final day, Marshall rebutted his opponents’ arguments. “The very people . . . that would object to sending their white children to school with Negroes are eating food that has been prepared, served and almost put in their mouths by the mothers of those children.”

Marshall wound up by saying all he asked for was equality. Black children would be expected to compete with white children without any special consideration. Teachers would be free to put “dumb colored children with dumb white children and smart colored children with smart white children.” In closing, he asked the Court to set a deadline of September 1956 for complete integration.

On May 31, 1955, the Court unanimously ruled against setting deadlines. However, school districts would have to start making plans to enforce integration. Local federal judges would ensure that schools desegregate “with all deliberate speed.”

Marshall wondered what that last phrase meant. Back in his NAACP office he griped about the decision to his lawyers. A secretary looked up “deliberate” in the dictionary. “The first word of similarity for deliberate is slow,” she said. “Which means ‘slow speed.’ ”

Marshall said, “Integration hasn’t happened yet, that’s how slow ‘deliberate speed’ is.” Yet he knew they had won their case. The Court remained committed to ending school segregation. “It will not take a hundred years,” he said, “that I can guarantee.”

Baltimore Afro-American editorial page cartoon, “. . . With All Deliberate Speed,” July 2, 1955. Publisher Carl Murphy felt that the ruling was a win for Marshall since the Court adhered to its plan to end school segregation in the United States.