Daily life in the castle in peacetime

The castle was the centre of a daimyô’s territory in more ways than one. The population may have depended upon the castle for their defence during wartime, but during peacetime the daimyô depended upon the population to grow food for the army, for providing a supply of recruits who would act as part time soldiers summoned in times of emergency, and also for castle maintenance. Apart from agricultural work, this was probably the greatest contribution made in peacetime by an individual peasant to the daimyô’s cause.

Big or small, all castles had to be maintained and many fascinating records have survived of the process. For example, in 1587 Hojo Ujikuni ordered a certain Chichibu Magojiro, the commander of a company associated with Hachigata castle, to maintain a 174 ken stretch of walls, plus one tower and three gates in that section. At four labourers per ken, the Chichibu contingent had to supply about 700 men to work on the walls of Hachigata. The rules were strict. If the man was a part time soldier who was away on campaign, his wife and maidservants had to come and make repairs. When the damage was due to a typhoon, they had to move immediately to make the repairs, and if the damage was to the gates, tower or embankments of the castle, they had to repair the castle first, even if their own homes had been destroyed. The daimyô’s needs always came first.

As well as repair, walls also had to be monitored as to their condition, and the area allocated to a particular company had to be policed and inspected once a month. The rope joints on the walls had to be fixed and frayed knots repaired during the last four days of every month, a time set aside specifically for this purpose. When the work was completed, it had to be reported to Hojo Ujikuni, and if he was away from the castle for any reason, it had to be reported to the appointed official. If a single person failed to perform his duty, a punishment was imposed on the whole company. Care had to be taken regarding the materials used for castle repair, and the members of the company itself had to make sure that any additional labourers they brought along with them used the right materials and were not negligent.

Waxworks inside one of the towers of Himeji showing the daimyô Honda Tadamasa (1575–1631) in a typical domestic scene.

The villagers thus impressed worked from the drum of dawn to the bell of evening, both signals being given from the castle tower. An earlier note, from 1563, spells out in more detail the schedule of repair. Barring typhoons, the walls were to be repaired every five years, at four persons per ken per day. The villagers had to bring with them at their own expense 5 large posts, 15 small posts, 10 bamboo poles, 10 bundles of bamboo, 30 coils of rope, and 20 bundles of reed. The instructions were as follows:

At intervals of one ken on top of the earthworks drive in the large wooden posts. Place two bamboo poles sideways between them, and arrange four bundles of bamboo on top using the small posts, fastened by six coils of rope and then thatched with the reeds.

These walls were coated with the mixture of red clay and rock noted earlier. Some castle walls were tiled above, rather than thatched, and the plaster finish could be given a top coat of white, giving the Japanese castle its characteristic graceful appearance.

The defence of a castle, of course, relied on more than stout, well-maintained walls. The men of the garrison were vital. Depending upon the size of the castle, the garrison could be permanent, rotated, or kept as a skeleton force. For example, the Arakawa company, located a few miles from Hachigata castle, were ordered to run to the castle when they heard the conch shell trumpet sounding an attack. An order from 1564 relating to Hachigata has been preserved, which requires the leaders of ‘company number three’, consisting of 13 horsemen and 38 on foot, to relieve ‘company number 2’ and serve 15 days garrison duty.

Garrison life in a samurai castle was a matter of constant readiness, with its own, sometimes boring routine. The Hojo had a strict system for the samurai of mighty Odawara. In 1575 they were required to muster at their designated wall prior to morning reveille. When the drum beat indicated the dawn they would open the gates in their sector to the town outside. Guard duty lasted for six hours during the day, with a two-hour break. The gates would be closed at dusk when the evening bell tolled. Guards were mounted at night, and had strict instructions not to trample on the earth walls. When off duty their armour and weapons were stored at their duty stations, but guards were posted in the towers day and night, and the utmost care was taken at night to prevent fires and to guard against night attack. Troops were not allowed to leave the castle for unauthorised reasons, and if someone did leave, he would probably be executed and the person in charge severely punished. In 1581 the Hojo orders for Hamaiba castle included some important considerations of hygiene and safety. Human excrement and horse manure had to be taken out of the castle every day and deposited at least one arrow’s flight away.

In the discussion above relating to the design elements of the typical Japanese castle no mention was made of those parts of the castle set aside for ceremonial functions. This is partly because few of these buildings have survived, but the topic must now be covered in detail because there are many records of castles being used to entertain ambassadors and for high-level meetings. In this context, possibly the most elevated use of a castle as palace was when Toyotomi Hideyoshi entertained the emperor of Japan with a tea ceremony in the gold-plated tea room of Fushimi castle.

The yashiki of Kakegawa castle, 1644

This plate shows the yashiki (mansion) of a daimyô that was built within the castle grounds, as distinct from the palatial areas inside a keep as shown for Azuchi on page 31. Lesser daimyô’s rooms would have been simpler, but all would have reflected the economy of style of traditional Japanese architecture, of which tatami mats, shoji (sliding screens) to divide a large area into rooms, and a tokonoma, or alcove, produced a harmonious yet restrained effect.

The Kakegawa yashiki has a total floor space of 947m2, and has 20 rooms with tatami floors, each room divided by fusuma (paper walls). The most important room is the shoin, which is subdivided into three parts:

1 Goshoin no kamino ma – the room where the lord sits

2 Tsugi no ma – the room where the interviewee sits

3 San no ma – waiting room

The daimyô’s private apartments consist of the working room, koshoin (4), and the living room, nagairoi no ma (5). The eastern section holds the offices, including the police station, finance department and the archives. The kitchen wing completes the ensemble.

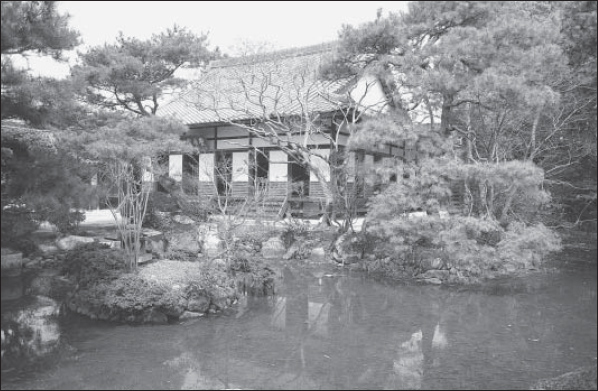

A view of the yashiki (mansion) of Kakegawa castle seen from the keep of the castle.

In many cases the ‘palatial’ areas of the castle were located in the keep, but this depended on to what extent the keep was designed for purely military purposes. For example, when Oda Nobunaga moved his capital to Gifu, as he renamed the recently captured Inabayama in 1564, all his domestic and administrative buildings were located at the foot of the high mountain upon which the purely military keep was located. By the time of the building of Azuchi in 1576, however, the military and the civic function of the castle had merged, so that Azuchi showed Nobunaga as both general and prince at the same time. This principle was emulated by Hideyoshi at Osaka, but at Osaka there were in addition some splendid reception rooms in the grounds.

A word that is frequently encountered in the context of the more domestic buildings of a castle is yashiki. It can be translated as ‘mansion’, and shows an evolution of styles comparable to the castle itself. At the time of the Onin War the rival daimyô lived in Kyoto in their own yashiki, all of which perished in the conflagrations that followed. From this time on a daimyô’s headquarters tended to be a well-defended castle, but the notion of a mansion lived on with those who felt most secure. Eventually, yashiki were to be found within the walls of the great castle complexes and castle towns. A very good surviving example is the Toda yashiki in Iga Ueno, which lies in an area of the town that was once within the outerworks of Iga Ueno castle. Within the Toda yashiki we can see the kitchens and bathhouse along with reception rooms. When the daimyô’s families were required to reside in Edo (a security measure introduced by the Tokugawa) numerous yashiki were created within the city, the distance of his dwelling from the keep being inversely proportional to the rank of the retainer.

A very good surviving example of a yashiki is the building which acted as the clan school for the Toda daimyô in Iga Ueno. It lies in an area of the town that was once within the outerworks of Iga Ueno castle. Here we see the main building looking across the pond in the garden.

Uniquely in Japan, at Nijo castle in Kyoto it is the military keep that has disappeared while the palace has survived. In other places we know about the design of the greatest yashiki because rooms from other castles have been removed and preserved elsewhere. Fushimi castle had outstanding reception rooms, some of which may now be found in the Nishi Honganji temple in Kyoto. Otherwise we can glean much information about yashiki, and reception rooms in castles generally, from the descriptions of European visitors, who were received in these surroundings by great men such as Nobunaga and Hideyoshi. For example, Luis Frois visited Gifu and wrote that ‘of all the palaces and houses I have seen in Portugal, India and Japan, there has been nothing to compare with this as regards luxury, wealth and cleanliness’. The long description that follows lists the reception rooms and gardens that made up Nobunaga’s palace at the foot of the mountain on which sat the purely military keep. When Frois visited in turn Azuchi castle he was able to see the same degree of ostentation within a castle keep. He mentions the lavish use of gold, and the whole thing was ‘beautiful, excellent and brilliant’. He also did not fail to notice the strength of the stone bases, and, like other visitors to Edo and Osaka, was most impressed by the strength of the gates.

Rodrigo de Vivero y Velsaco had an audience with Tokugawa Hidetada, the second Tokugawa shogun, at Edo castle in 1609, and described the first room he entered as follows:

On the floor they have what is called tatami, a sort of beautiful matting trimmed with cloth of gold, satin and velvet, embroidered with many gold flowers. These mats are square like a small table and fit together so well that their appearance is most pleasing. The walls and ceiling are covered with wooden panelling and decorated with various paintings of hunting scenes, done in gold, silver and other colours, so that the wood itself is not visible.

Lesser daimyô’s rooms would of course have been simpler, but all would have reflected the economy of style of traditional Japanese architecture, characterised by the use of tatami mats, shoji (sliding screens) to divide a large area into rooms, and a tokonoma or alcove.

When war began the daily lives of its garrison and the local population changed rapidly as the castle was converted into an active military headquarters. The Ou Eikei Gunki, a chronicle that deals with wars in the north of Japan, describes the extra preparations a garrison had to make when threatened with a siege. The following descriptions occur in the section that describes the defence of Hataya Castle in 1600 by Eguchi Gohei. Note how the castle is prepared for assault, which the attackers then convert into a siege when the attack is resisted.

One of Yoshiaki’s retainers called Eguchi Gohei kept the castle of Hataya, on the Yonezawa road. When he heard of the treacherous gathering at Aizu, he immediately replastered the wall and deepened the ditch, piled up palisades, arrows and rice, and waited for the attack … The vanguard were under the command of Kurogane Sonza’emonnojo, with 200–300 horsemen. He sounded the conch and the bell to signal the assault. As those in Hataya were approached by the enemy they attacked them vigorously with bows and guns. Seventy of the enemy were killed in one go, and many were wounded. The deaths led to a change of plan, and the army who had tried to take the castle came to a halt.

The main hall of the Toda yashiki in Iga Ueno, showing the classic simplicity of style found in Japanese architecture in buildings both great and small.

The state of a castle’s food supplies was crucial when it was about to be besieged, or when such a prospect seemed likely following a enemy incursion. In 1587 Hojo Ujikuni ordered the village of Kitadani in Kozuke province to collect and deposit all grain from the autumn harvest in his satellite castle of Minowa. The value placed on provisions is also given dramatic illustration by another order from Ujikuni issued in 1568, the same year that Takeda Shingen invaded western Kanto, that no supplies were to be moved without a document bearing the seal of the Hojo. Should anything be moved without the seal then the offender would be crucified. Such draconian measures were justified because the threat of starvation could seal a castle’s fate. After a 200-day siege in 1581 the defenders of Tottori were almost reduced to cannibalism. The strangest device for combating starvation may be found at Kato Kiyomasa’s Kumamoto castle. Not only did he plant nut trees within the baileys, but the straw tatami mats that are to be found in every Japanese dwelling were stuffed not with rice straw but with dried vegetable stalks, so that if the garrison were really desperate they could eat the floor.

A reliable water supply was also vital during a siege. The sixth chapter of the Taiheiki, concerning the siege of Akasaka in 1331, tells of how 282 warriors in the castle came out to surrender, because they knew they would die the following day because they could not support their thirst for water. If a besieging army could locate the source of a garrison’s water supply and destroy it they acquired a tremendous advantage. During the siege of Chokoji castle in 1570 a decisive moment was reached when the besiegers succeeded in cutting the aqueduct that supplied the garrison. All the defenders then had left were the meagre supplies stored in huge storage jars. This led to the celebrated incident when Shibata Katsuie smashed the jars and led his men out in a desperate assault that actually won the battle for them. The Zohyo Monogatari further notes that:

Interiors of a keep are difficult to photograph adequately, but this corner inside Matsumoto shows several typical features. Note how there is a corridor running round the edge. The floor in the centre would be fitted with interlocking tatami mats. There are two gun ports at the apex of the corner, and two rectangular windows.

During sieges on a yamashiro when there is no further water the throat becomes parched and death can result. Water rationing must be carried out, to a measure of one shô per person per day.

In two of the Takeda campaigns the water supply played a crucial role. At Futamata in 1572 the castle obtained its water by lowering buckets from a wooden tower built high above the neighbouring river. Takeda Katsuyori constructed heavy wooden rafts and floated them downstream to crash into the supports of the tower, which eventually collapsed. At Noda in 1573 miners tunnelled into the side of the castle’s moat and drained off all its water.

The numbers of people within a castle were swelled by farmers and others moving in for safety when an attack was imminent, and this could stretch the garrison’s resources and provisions to their limits. When Takeda Shingen invaded the Kanto in 1569 the local people flocked to Odawara, causing severe pressure on resources. During Hideyoshi’s invasion of the Hojo territories a much larger movement of population took place, and the garrisons of nearly all the Hojo satellite castles were stripped to the bare minimum while most troops were packed into Odawara. Hojo Ujikuni’s Hachigata castle was the sole exception, and came under concerted attack. Hideyoshi’s support forces under Uesugi Kagekatsu and Maeda Toshiie spread 35,000 troops round Hachigata, and after a month-long siege Ujikuni surrendered, thus providing a foretaste of what was to come at Odawara. Starvation was but one of the weapons Hideyoshi employed at Odawara, and to drive the point home the besiegers created a town of their own around the walls, where they feasted loudly within sight of the defenders.

While the garrison of a castle were preparing for a siege, the attacker would be similarly organising his forces and engaging in political negotiations that could result in a bloodless victory. This was far from uncommon, and a good example occurs during Toyotomi Hideyoshi’s campaign against the Mori family on behalf of Oda Nobunaga. The first castle Hideyoshi had to face was Himeji, which was then called Himeyama. It lay where two key roads met. The castellan was a certain Kodera Yoshitaka, whose loyalties were somewhat unsure. Through the mediation of Kuroda Yoshitaka, Kodera’s son-in-law, Kodera was persuaded to surrender Himeji without a shot being fired. With Himeji as a base Hideyoshi could then concentrate on capturing Miki castle, which was also in Harima province. It was held by Bessho Nagaharu, whom Hideyoshi wished to spare so that he might join the Toyotomi side as well. Hideyoshi wrote to Kodera Takatomo as follows:

I am despatching Hiratsuka to you promptly, and order you to take stock of the situation and save the life of the lord of Miki. If you manage to isolate it completely, you can take Miki by cutting off supplies of food and water, for there have been many such occasions when the besieged have pleaded for their lives. After you have finished with Miki, please do not neglect to capture Gochaku and Shigata. You can take them either by starvation or by killing … As far as [the lord of] Itami [Araki Murashige] is concerned, it seems to me he will be defeated in three or five days because you have filled the moat in so quickly.

The keep of Matsue castle, one of the best preserved of Japan’s ‘black castles’. Note in particular the extension of the stone base to form the walls of the entrance.

Not all the elements of Hideyoshi’s carefully considered plans worked. He won Miki castle, but the castellan, Bessho Nagaharu, preferred to commit suicide rather than submit personally, and Araki Murashige, lord of Itami, managed to escape and rejoin the Mori.

When the matter came to an assault, an attack on a defended castle provided a samurai with opportunities for individual glory every bit as dramatic as a field battle. Siege work was less glamorous, but no less eventful, as the following section will demonstrate.