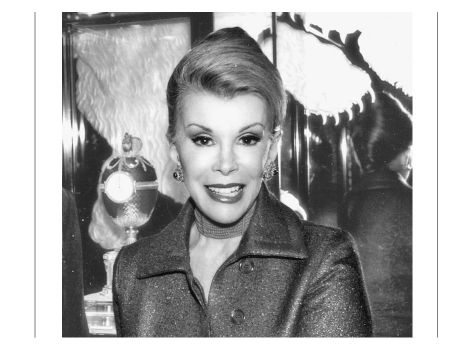

Joan Rivers

I HEAR JOAN RIVERS before I see her. “I’m coming! I’m coming!” she bellows from the elevator as she rides up to her private floor, where I’m waiting in her showily ornate Upper East Side town house. She’s running late, but her assistant, Jocelyn, a friendly, no-nonsense type, has made me feel at home in an extremely formal parlor. It is stuffed with fancy things that hover between chic and gaudy: leopard carpet, dog statues flanking a fireplace, large tufted leather sofa, and embroidered pillow emblazoned with the adage, “I need a man to spoil me or I don’t need a man at all.”

A butler—an actual white-jacketed butler named Kevin—has already brought me mineral water and pastel-colored cookies on a silver tray. I could get used to this. Jocelyn explains that her boss is rushing back from the annual Central Park Conservancy luncheon, which is known for its attendees’ extravagant hats. “I hope she’s still wearing hers,” I tell Jocelyn. “Oh, she’ll keep it on,” she assures me, “because you don’t want to see her hair underneath.”

Soon Rivers, seventy-two, appears in all her riotous finery—a hot pink satin suit with ruffled black chiffon blouse, black hose and matching fuchsia hat whose brim barely gets through the door. It’s a loud entrance befitting the arbiter of awards show taste. “I’m sorry I’m late,” Rivers apologizes, as her three dogs—Veronica, Yorky, and Max—yap at her arrival.

She doesn’t take the time to change into something more comfortable, and I worry that she can barely sit down in that tight pink skirt. Despite the surfeit of inviting furniture in the parlor, Rivers perches on a tiny ottoman opposite me (Jocelyn set it up ahead of time, knowing, I suppose, that’s her preferred interview seat), and takes off her hat. “Please excuse my hair,” she says, “this is really hat hair.”

She actually seems human all of a sudden, despite her getup, despite the surgically taut face, despite decades of studied celebrity. And I’m surprised, frankly, at how bluntly, tribally Jewish she is. “The Jews take care of everything and everyone hates the Jews,” she says. “The blacks hate the Jews. You fools! Who marched with you? Who marched with you? Not the WASPS. Trust me; not the WASPS.”

She’s fanatically watchful of anti-Semitism being more barefaced recently. “Oh, it definitely is. Look around,” she insists. “Queen Noor’s book is number one on the New York Times best-seller list!” She’s referring to the former first lady of Jordan, an American-born, half-Lebanese Princeton graduate who married King Hussein and wrote a book about her life in the Arab world. “Jewish people—Jewish friends of mine—went to her book signing!” Rivers moans. “Her book has overt anti-Semitism! I had a Jewish doctor of mine say, ‘No, no, no; she’s my patient; she’s not anti-Semitic.’ I got so upset on the examination table. ‘Read the fucking book!’ I yelled at him. ‘Read the New York Times review—you don’t even have to buy the fucking book!’

“I did something at a dinner party.” Rivers isn’t done with Noor. “I got her back. For the Jews. She was on one side of this host, who is a very famous person—I don’t want to give names—and I was on the other side. And the host was supposed to talk to me for the hors d’oeuvres because I was the lesser guest, and then talk to her for the main course. And the gentleman spoke to me for the first course, and then I thought, ‘I’m going to keep him so amused, he’s not going to talk to that bitch for the main course.’ And I kept him talking to me for the whole dinner. And I thought to myself, ‘That’s for the Jews.’ I’ll fix you, Queen Noor, you anti-Semite! Number one on the best-seller list! And who buys the books? Jews!”

Her loyalty is rabid and Israel has become her litmus test. “Let me tell you something: I left Clinton because he left Israel, and if Bush is in there defending Israel, I’ll defend Bush. That’s where my allegiance is. I’m the reverse of the Dixie Chicks.” She laughs. “Because Israel is not going to go down the tubes with Bush—we hope.” She thinks the Holy Land is truly in peril. “I worry that they’re going to wipe it off the earth. I only hope that they’ll take us all with them. Because Jews shouldn’t go quietly this time. If they’re going to kill us, we’ll kill you right back.”

Rivers—formerly Joan Molinsky—grew up in Brooklyn on a street known as “Doctors’ Row,” since so many physicians lived there. She remembers that during the war children were being sent from Europe to safety in New York. “There was always some doctor who had a niece or a cousin from Prague coming to live with them. And that’s because these were kids that were being snuck out. I remember we lost relatives in France. I was old enough, in 1945, to hear all the Holocaust stories. The one that stays with me was one of the good Holocaust stories: An uncle was hidden through the whole war in one of his patient’s cellars. And we had another uncle whom my mother was sending clothes to, who wrote us about a jacket he received: ‘When I put my hand in the pocket and I found gloves, I felt like a gentleman again.’”

When the Molinskys moved from Brooklyn to Larchmont—a New York City suburb—Rivers’s father founded the temple there. The congregation met in the firehouse in its early days “because there were so few Jewish families,” Rivers explains, and her dad was the cantor until they found a professional. She is still proud of her father’s gifted voice. “He sang to the end,” she says wistfully.

Two anti-Semitic incidents stand out from childhood. “I was having my teeth cleaned at our dentist, and he said, ‘You’ll never make a good college because you’re a Jew.’ I was twelve. But see, that was good for me, because even then I thought, ‘Oh yeah? Want to bet?’ It was almost like an impetus: ‘I’ll show you, Doctor.’

“The second one was when I got a summer job in the junior department at Wanamaker’s; I was fifteen and I worked all summer with another girl. And the last week she turned to me and looked at something on the clothing rack and said, ‘Ech, only Jews would buy this.’ And I was in shock. We’d worked all summer together.”

Rivers attributes much of her moxie to her ethnic constitution: “Maybe it’s that Jewish immigrant ethic of ‘I will do it’ that I still have to this day.” Her fists go up. “Don’t you dare tell me I can’t do it. I always say to [daughter] Melissa, ‘Jews are smarter, we’re brighter, and we can do it better.’”

We discuss Jews’ reluctance to be viewed as too Jewish. “That’s about class,” she asserts. “It goes back to all of us who are now a little more educated, polished, assimilated; you don’t want to be that stereotyped, big-mouthed lady with too many diamonds.” (This is said without any discernible self-irony.) “There are certain clubs I know I can’t get into even now. All my friends belong. I don’t even want to be in them. No matter what—I could stand on my head—I’ll never be in the Everglades Club. Across the street,” she gestures outside, “if there’s ever a problem, I can never go into the Metropolitan Club.”

Did she ever feel she looked too Jewish? “Oh, I know I do!” She laughs heartily. “I look at pictures of myself and I look like what I am: a middle-aged or old Jewish matron. There it is. You are what you are. But I’m also so proud when it’s a Jew that wins the Pulitzer Prize or the Nobel Prize. And conversely, I’m always so glad when the serial killer isn’t Jewish.”

She concedes there are times she wishes she had a different religion: “Every time I see a good-looking German guy in leather.” She laughs again. “Show me a blond blue-eyed guy in leather and I’ll say, ‘Oh, what a pity I’m Jewish!’”

But her parents instilled an unshakable self-respect and urged her to marry within the faith. “It was important to me, too,” she adds. “First of all we’re the chosen people, and I like that we’re continuing; I don’t want it to stop. If these people have struggled thousands and thousands of years, it should not stop with me. Who am I to say, ‘You buried your candles during the Inquisition and now I’ve decided not to continue’? And I love going to temple—I love Rosh Hashanah, Yom Kippur, Hanukkah. And then when Hanukkah’s over, I do the biggest Christmas tree you can imagine! But I love the Jewish tradition. On Passover, I look forward to doing my meal. I love when you break the fast on Yom Kippur.” She fasts? “No. Never have. I don’t think God cares.”

She says she feels moved in temple when she hears prayers like the Shema. “At those moments, I’m in the right place and I’m doing something I’ve done every year of my life and it’s a tremendous landmark for me. And if I don’t go to synagogue on Yom Kippur night, I’m devastated. I missed one once.” It was eighteen years ago, Kol Nidre night, when she and Melissa walked into their usual synagogue on Fifth Avenue, Temple Emanu-El. “My husband, Edgar, had just killed himself in August, and we went into the service here in New York and it was pouring rain and we were ten minutes late—with tickets!—assigned seats! And some smart-ass said, ‘You can’t come in.’ And we said, ‘We’ll sit in the back.’ And he said, ‘You can’t come in.’”

Distraught, she decided to salvage the holiest day of the year by going shopping. “I took Melissa and we went to Ralph Lauren. Polo. And we bought. I said, ‘We’re going to do something to make this better.’ And then the next year on Yom Kippur, we were walking into temple, and that bastard came to me and said, ‘Surprise! I’m the one that didn’t let you in last year.’ And I said to him, ‘I only hope it happens to your family.’ And he said to me, ‘It’s Yom Kippur! How can you say a thing like that?’ And I said, ‘Look what you did to me on Yom Kippur!’”

When Edgar Rosenberg died, Rivers found the Jewish ritual of sitting shivah for a week—receiving friends and family at home—to be curative. “Oh, I think it’s wonderful,” she says. “It makes sense! Seven days of eating and talking and laughing and crying and being in the house is so great because you’re so happy to be quiet finally when everybody goes home. It’s so brilliant: Then you’re so happy to be able to go out of your house again. And meanwhile they’ve kept you going. Shivah’s wonderful.”

She says she also drew strength from a heritage of pluck and perseverance. “It’s all about survival. My husband’s entire family was killed in the Holocaust; I have a little pillbox upstairs that’s all that’s left of his German family. So I’m not here to fall apart.”

The Holocaust seems to be at the forefront of her consciousness. Even when she watched Melissa costar in the ludicrous ABC reality show I’m a Celebrity, Get Me Out of Here! (2003), she connected it to Auschwitz: “When Melissa came back, I said to her, ‘I watched you on that program and thought to myself, ‘You could have survived the death camps.’ That’s where the mind of the Jew goes, watching someone go through what Melissa was doing. I said to her, ‘You were strong enough; maybe you would have gotten through.’”

After her husband’s suicide in 1987, she eventually started dating again. “I was going out for a while with a man who was very Jewish. And I loved that; he lit the candles and cut the challah, and I loved that. I loved everything but this man.”

Was it important to her that Melissa marry someone Jewish? “Not as important,” Rivers says as she shakes her head. “Because I could see the handwriting on the wall, and I don’t know why.” In other words, she could see Melissa gravitated toward non-Jewish men, despite her upbringing. “She came from a Jewish family, we had the traditions, she went to Sunday school, but she’s never connected with Jewish boys. And it makes me terribly sad, because I still believe all the clichés: They still make the best husbands.” How so? “I think they’re more for home and hearth. I think they’re really into their work. They don’t drink as much. Everything they laugh about is absolutely true. And so I was quite disappointed.

“Melissa was going out with him [John Endicott] for seven years, so it’s not like, when they decided to get married, I fell against the door and clutched my heart. Obviously this was what was coming down the pike. But it made me very sad. I always had the fantasy that he would see how great Judaism is, how logical and ethical it is, and he would end up saying, ‘This is what I want.’ But we never got to that.” Endicott and Melissa divorced five years after the wedding—an interfaith ceremony that still makes Rivers shudder. “We had a rabbi and a minister—you know, one of those terrible marriages. I mean, what’s the baby going to be?”

Indeed: What is the baby? Edgar Cooper Endicott, according to his grandmother, is absorbing the traditions of the parent he’s with most: mom. “He’s with her now, and the mother’s Jewish, and so it’s whatever you come out of,” Rivers says. In other words, custody is destiny. Before the separation, Melissa did not welcome her mother’s questions about how her grandchild would be raised. “It was always, ‘We’ll make the decision,’” Rivers recalls. “I pushed because I just didn’t want him to be nothing. But then I thought to myself, ‘Don’t worry: I’ll get him in New York for Passover, Hanukkah, Yom Kippur. He’ll know what he is.’”

Though Rivers clearly has a clannish instinct, she says she wasn’t conscious—during most of her career—of who the other Jews were in show business. “But now, I am more aware and I’ve started to use it.” She explains that there was a “new regime” of executives at the E! Channel, where she was a host, and she couldn’t break the ice with them. “I finally turned to one of them and began to talk about Sunday school. And we now talk to each other as Jews! I just got flowers from them with a note that said, ‘The mishpucheh [family] loves you.’ I said to Melissa, ‘I don’t know if I’m shitting them or they’re shitting me.’ Cause we’re all connecting on this big Jewish level now. But generally, I don’t think that helps at all in the business—the way AA [Alcoholics Anonymous] members have each other or gays have each other. I don’t think that’s there for Jews. It’s never been there for me.”

And despite the fact that she is in many ways the archetypal Jewish celebrity, she says that she’s not the one Jews put up as the famous face of Judaism. “Oh, I only wish I were! Are you kidding? Oh, how wonderful to say, ‘She’s the one we look to.’ I think they look to Barbara Walters, this age group. Which is stupid. Come over here! It’s more fun over here!”