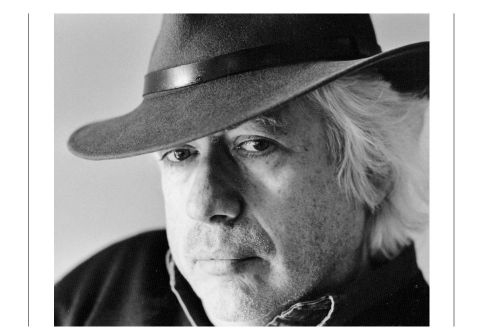

Leon Wieseltier

LEON WIESELTIER PHOTOGRAPHED IN 2005 BY JILL KREMENTZ

ONE OUT OF EVERY FIVE PEOPLE I talked to about this book said, “I assume you’re talking to Leon Wieseltier.” One prominent magazine editor referred to him as “The Grand Poobah of Judaism”; others called him simply “Super Jew.”

The literary editor of The New Republic for the last twenty-one years, Wieseltier is, in his spare time, a rumpled encyclopedia of Torah commentary, Jewish philosophy, and Talmudic law. He is fluent not just in Hebrew, but in libraries of obscure Jewish texts. His book Kaddish was a chronicle of the year—1996—that he spent going to synagogue the required three times daily to say kaddish for his father. He excavated, it seems, every conceivable discussion from every imaginable rabbi who ever had an opinion, all in the effort to make sense of this one prayer for the dead. A fifty-three-year-old graduate of Columbia, Harvard, and Oxford, Wieseltier is also the author of Nuclear War, Nuclear Peace, and Against Identity , and has written more essays and sat on more panels than it would be possible to enumerate.

I meet him in his Washington office at The New Republic—a sterile space which he’s managed to make a little scruffier thanks to haphazard stacks of books on the carpet, couch, and bookshelf and careening heaps of papers on his desk. He’s wearing jeans and cowboy boots; his trademark Einstein-like thatches of white hair are appropriately unkempt. He turns off his Mahalia Jackson CD so that it’s quiet enough for my tape recorder, and he seems genuinely startled that I actually finished Kaddish , which even he refers to cheerily as “my turgid tome.”

Some warned me that Wieseltier would be disdainful of my ignorance in Judaic matters, but I didn’t find that to be true: rather, he’s disdainful of Jewish ignorance in general. Nothing personal. “I think the great historical failing of American Jewry is not its rate of intermarriage but its rate of illiteracy,” he says. “I can go on for many long hours about this. The amount of Judaism and the Jewish tradition that is slipping through the fingers of American Jewry in times of peace and security and prosperity is greater than anything that has ever happened in the modern period anywhere. It is a scandal. Now what I’m not saying is that there should be more believing Jews or more belonging Jews; this is a free country. We believe in freedom; people can think and do what they want. The problem is that most American Jews make their decisions about their Jewish identity knowing nothing or next to nothing about the tradition that they are accepting or rejecting. And a lot of American Jews accept things out of ignorance, too. The magnitude of American Jewish ignorance is so staggering that they don’t even know that they’re ignorant.”

I tell him he sounds judgmental. “I judge it very harshly,” he agrees. “I loathe it. Because we have no right to allow our passivity to destroy this tradition that miraculously has made it across two thousand years of hardship right into our laps. I think we have no right to do that. Like it or not, we are stewards of something precious; we are custodians, trustees, guarantors. We inherit the language in which we think, we inherit most of the concepts that we use, we inherit all kinds of habits, and one of the things we inherited is this thing called the Jewish tradition.”

He brings to mind two lines in his book, Kaddish, which stuck with me: “Do not overthrow the customs that have made it all the way to you.” Also, “Sooner or later you will cherish something so much that you will seek to preserve it.”

But many of the people I’ve spoken to say they’re turned off by the amount of time observance requires, the rigors of ritual. “Come on,” he interrupts me. “That is a miserable excuse. We’re talking about people who can make a million dollars in a morning, learn a backhand in a month, learn a foreign language in a summer, and build a summer house in a winter. Time has nothing to do with it. Desire, or the lack of it, has everything to do with it. It’s about what’s important to people. We’re talking about intelligent, energetic individuals who master many things when they wish to.”

That said, he has capacious sympathy for someone who engages the tradition, but then decides to forgo it. “I don’t mind when Jews tell me it’s not important to them. I feel sad, but they have a right to decide it’s not important to them. That is the risk you run in living freely, and we should be happy to run that risk. Who would not prefer the danger of ignorance to the danger of extermination? But I would much rather people say, ‘I don’t care to be Jewish anymore.’ The bad faith of the noisily faithful makes me crazy.”

He derides a kind of Jewish identity that might be described as Judaism Lite—an identity tied to ethnicity, not education. In other words, Jews who “feel” Jewish because of a tune they remember, a cheese blintz, or a visit to shul twice a year. “Owing to the ethnic definition of Jewish life, there has occurred a kind of internal relativism among all things Jewish,” he says. “If we’re just a tribe, if we’re just an ethnic group, then all of our expressions are equally valuable, they all delightfully express what we are. ‘I like Maimonides, you like knishes, but we’re Jews together!’ Right? The philosophy, the food, it’s all different ways of being Jewish. But if you invoke the old Jewish standard, the traditional standard, all this falls apart.”

And that standard is? “The standard is competence,” he answers. “The standards by which Jews should be judged are not American standards; they are Jewish standards. That is to say, if one is making judgments about the quality of Jewish identity of individuals or groups, that the criterion has to be taken not from the society in which we live but from the tradition that we have inherited. And that’s where I think Jews are going to be found to have been criminally negligent.”

But why? How does he explain why so many people essentially dropped the rituals that used to define being Jewish? “Whereas American society does require the thing we call ‘identity,’ it doesn’t require that the identity be religious and it doesn’t require that the identity be thoughtful,” Wieseltier answers. “More so than it’s ever been before, the ethnic or tribal dimension of Jewishness has been brought to the fore in this country. Especially since the ethnicization of American life since the late 1960s. So it is very possible in this country, where you are expected to be a hyphenated individual, for the non-American side of the hyphen—in this case the Jewish side—to be entirely an ethnic or tribal or biological sensation of belonging. That’s enough for Jewish identity, American style.

“American Jews, like Americans, have a very consumerist attitude toward their identity: They pick and choose the bits of this and that they like. They ornament themselves with these things, they want to bask in the light of these things . . . Most American Jews don’t see identity as an enterprise of labor, a matter of toil. It’s something automatic that confers upon you a certain status. As I say, a form of luck.

“So in America now it is possible to be a Jew with a Jewish identity that one can defend and that gives one pleasure—and for that identity to have painfully little Jewish substance. The Jewish substance of Jewish identity is not necessary, or it is minimally necessary.”

I tell him that many of the people I’m talking to feel great pride in being Jewish, whether or not they’re students of Judaism. “Generally in American Jewry, pride exists in inverse proportion to knowledge. So you will often find that the more learned or knowledgeable Jewish individuals are, the less strident and hoarse with self-admiration they tend to be. And the ones who know very little are looking for anti-Semites everywhere, because they need enmity to sustain their Jewishness. (It doesn’t matter that sometimes they find it. We were never Jews because there were anti-Semites.) They think that the best way to express Jewishness is by fighting for it. And so in this way pride does the work of knowledge, sentimentality does the work of knowledge.”

So when he says that Judaism has failed— “No—” he stops me. “Judaism hasn’t failed. The Jews have failed Judaism.” But those who taught Judaism failed somewhere along the way, too, it seems, if there are so many disaffected people. “Yeah, I think that’s true,” Wieseltier concedes. I venture that if all the bored temple-goers had had someone to turn them on to Jewish traditions and texts, they might— “But you know what?” Wieseltier breaks in. “You have to want to be turned on. That’s like saying, ‘There’s no point in going into the record store, because almost all the records in there are terrible.’ But you go into the record store because there’s one record you really really dig. I mean, nobody ever didn’t walk into a record store to buy a Charlie Mingus record because there was a Keith Jarrett record for sale, too. Again, it’s all about what’s important to you. It’s about motivation and will; about one’s expectations of oneself, about what makes the world tingle for you. It’s about the tingle.”

Wieseltier certainly hasn’t lost the tingle, even though he did lose the Orthodoxy with which he was raised. (The son of Orthodox Eastern European parents, he attended Yeshiva of Flatbush.) One day, he walked away from all of it. “I was alienated from shul for lots of reasons,” he says, “and I had philosophical problems with my picture of the world and I resolved that I would not go through my life without food, wine, or women.”

He explains why those pleasures were off limits: “I was an Orthodox boy. I wasn’t allowed to put my hands on girls or have a good bottle of red. I decided for reasons of personal hunger and philosophical perplexity and real alienation from the synagogue that I had to wander.”

Was there literally one precise day when he stopped living by the rules? “There was a day I took my yarmulke off in my senior year of Columbia College,” he answers. “And then my first violation of the shabbos was a phone call to Lionel Trilling. And my first cheeseburger was at a Patti Davis show at CBGB’s. And my first cheese pizza was at V & T’s. I remember that Art Garfunkel was sitting at the next table.”

How guilty did he feel? “It depends when and where. There’s also enormous pleasure associated with sin, as you may have heard.”

But his internal religious clock was unshakable. “Even when I was allegedly gone, I always knew that Friday night was shabbos. I always knew that, when I was eating something I shouldn’t eat, something I shouldn’t eat was what I was eating. I was never indifferent to it; I was never dead to it.”

He said his parents were not dismayed. “My parents knew how much I loved the tradition and they saw that I was devoted to it intellectually. They saw that the whole way. They were a little perplexed about how one could be so ardent a Jew and still live at such a distance from religious practice. They were perplexed. But it would have been harder for them if I had started my literary life with essays about, say, Mallarmé, and not with essays on Jewish subjects. So even if they were perplexed, they knew their son’s Jewish heart, they had confidence in it, and they were right. I may have been a weird or troubling case, but I never left. I could never leave. It was a matter of honor, but also it was a matter of love.”

Love?

“I have an erotic relationship with Judaism. I really do. Judaism is the instrument that opens up the world for me. The world doesn’t open up Judaism for me. The history of the Jewish people is one of the greatest human stories, obviously. So if you go and study Jewish history, you can’t do it just to study about the story of how this magnificent people finally climaxed in the birth of yourself. It’s not about, ‘How did I get to be me?’ It’s about what human experience is like and what are the extremes of human experience, internal and external. That’s what Jewish history is about because of what happened to Jews.

“And similarly, philosophically, this tradition gives me the words and the instruments to break into the universal questions. And that’s one of the things I tried to show in my turgid tome. You take this highly specific, highly particular thing, this concrete tradition, and you use it to break open the universal questions. That’s what our tradition is for. It’s not there to be smugly particular or to keep one in love with oneself. If the Jewish tradition is beautiful, it’s not because it’s my tradition. It’s a great human tool. And everyone needs a tool.”

One crucial implement, Wieseltier believes, is the Hebrew language. “On the question of Jewish literacy, of the need for—and the beauty of— Jewish languages, of Hebrew, I’m an evangelist. I speak to American Jews about Hebrew till I’m hoarse. The first words my little son heard were Hebrew and I sing Hebrew songs to him and he got his first Hebrew books with his first English books.” Wieseltier’s son is fifteen months old at the time of our meeting.

Why is the language itself so important? “Because I think to be a Jew is not to be an American or a Westerner or a New Yorker,” he replies. “To be a Jew is to be a Jew. It is its own thing. Its own category, its own autonomous way of moving through the world. It’s ancient and thick and vast and it’s one specific thing that is not like anything else. And though it converges with other identities and other traditions and other ways of going through the world, it’s not them. And one of the ways Jews should go through the world is in the Jewish language. You cannot really know what Judaism is if you drop the Hebrew; it just can’t be done. And the joke is: We have Jews who couldn’t care less about this but would be absolutely scandalized if you suggested that they go to a performance of Die Walküre in English. They’d think you’re accusing them of loving kitsch. They’d be absolutely outraged. And if you suggest that the drawing that hangs over their sofa is a reproduction, they’d get really offended. But their Judaism, at least from the standpoint of literacy, is a reproduction. And that’s okay with them. It would be comic if it weren’t tragic.”

It’s implicit in our discussion that most of the accomplished Jews I’m talking to for this book wouldn’t meet Wieseltier’s standard of Jewish “competence.” I suggest that maybe it’s because the most successful are kind of hyper-assimilated, and for various reasons dispensed with rituals along the way. “The question is does their assimilation have any integrity?” he asks. “I don’t mind assimilation—we’re all assimilated. In fact, assimilation is a good thing. It’s about, what are the grounds for their Jewishness? What have they decided to be and not to be? What are their reasons? And the scandal is, they often don’t have reasons. It’s very lazy. They just don’t care. And this is not worthy of respect.

“I can respect heresy, I can respect alienation, I can respect Karamazovian rebellion, even Oedipal rebellion (up to a certain age, when the statute of limitations on childhood rage runs out); there’s some grandeur to all of that. Say you hate it. Say you hate your parents so much, you can only eat pork. Or deny that there is a God. Or say the Jews are stealing the air from your lungs and if you don’t get out, you’re going to die. Just say it and then we can talk about it . . . I don’t mind renegades or apostates. Again, I really have a lot of respect for the renegades and the apostates and the angry ones and the bitter ones. Jewish history is full of such people. And there are good reasons to be angry and alienated. Sometimes I think that the synagogue is Judaism’s lead bulwark against spiritual life. There are many reasons to be angry. And Hebrew school is a halfhearted effort that led to a halfway house that alienated more people than would have . . . but we’re not talking about that. My point is that most American Jews are not renegades; they are slackers.”

So if someone says, I go to High Holy Day services; I sit there, but the words mean nothing to me? “I say: Then don’t go,” Wieseltier replies, “or learn the words. But what you just described is what I can’t stand. If the words mean nothing to them, they shouldn’t go. They don’t go to Chinese opera either. But they’re not prepared not to go, because that would involve accepting the responsibility for their tradition. Instead they want to inherit something passively, like all inheritance. So I say to them: Don’t go, and deal with the paltriness of your Judaism. Or, if you’re sincere in your complaints, take two weeks out of your busy and sophisticated year and learn the words. That’s all. And then come back and tell me that it’s still so boring.

“The truth is that anger is a form of connection. So anger’s fine. The great freethinkers in modern Jewish history were people with whom believers always talked and debated. Because they knew what it was that they turned away from. You can spend hours arguing with someone who completely rejects what you completely accept because you both know what you’re talking about and it’s a primary discussion.”

But if someone who values their Jewish identity yet doesn’t practice its traditions says, My Jewishness is just a part of me—it’s who I am, it’s in my blood, why doesn’t that count for something?

“Then I would say to them, ‘That’s fine; but you have just admitted that your Jewishness is a trivial fact about you. And you won’t be insulted if I consider it a trivial fact about you.’”

Wieseltier’s bottom line is clear: His disappointment is not that Jews are marrying out of the faith or assimilating beyond recognition, but that their Jewishness is flimsy. “Basically there are two questions,” he says. “The survival of the Jews and the survival of Judaism. I don’t worry too much about the former.”

Why not? “Partly because history gives me a paradoxical hope, and partly because I have a mystical confidence in the eternity of our people. When I regard all the things that have happened to Jews and to Judaism in all of Jewish history, I come away bitter, of course, and angry, of course, but also astounded by our perdurability. And we’ve been in much worse shape than we are now. Many, many times. I don’t like Jewish hysteria. In fact, I think hysteria is sometimes used as a way to avoid having the toil of Jewishness. Some American Jews think if you want to be a good Jew, all you have to do is worry. Worry will do the work of your Jewishness. There’s this game that Jews play: Who worries most? And whoever worries most wins. Whoever is the most hysterical is the most faithful. It’s stupid.”

But even if he’s not himself worried about Jewish survival, does he understand the obsession with Jewish continuity? “Of course. There should be an obsession about continuity. But there’s something even about the word ‘continuity’ that’s so cold and formalistic. It’s sort of a kind of real estate term or something. Continuity of what? The fashion for klezmer: That’s continuity, too. But as far as I’m concerned, that’s also discontinuity. Because the Jewish tradition is essentially a verbal tradition, and no amount of clarinet playing—or Carlebach singing, or John Zorn screeching—is going to disguise that fact.

So the question remains: continuity of what, exactly? What matters more and what matters less? In American Jewry, what matters more tends to be the aspects of the tradition that are less intellectually taxing and more emotionally immediate. I understand why our leaders and rabbis worry about the rate of intermarriage. But let’s say that more Jews start marrying more Jews. Then what? There’s still the question of the happy couples’ relationships to the tradition. Is it enough that Epstein married Rosenblatt? I guess that’s something. But then what do Epstein and Rosenblatt do next as Jews? I don’t like tribalism. I don’t like tribal definitions of identity. Jews should not think the way Serbs do. The sick joke about tribes is that all tribes think that they are chosen people. Too much of our talk about continuity and too much of our anxiety is tribal anxiety.”

Wieseltier also bemoans a phenomenon he calls “Jewish self-love.”

Which means?

“The smugness that Jews feel about themselves as Jews. They’re in love with themselves.”

I propose that maybe this self-congratulation has something to do with Jewish survival—the fact that Jews had to build themselves up over the centuries because they were in danger of being wiped out.

“Yes, but it has to be earned. The love has to be earned. We’re taught that the highest form of love is unconditional love, but that’s wrong. The highest form of love is conditional love, because if you’re still being loved, that means you’re earning it. It has a foundation in what you really are. I don’t want to be loved no matter what I’m like. Such love is insulting, except from parents. Which is to say that unconditional love is a form of infantilization. No one should ever want to be loved the way their parents loved them. Except by their parents. That’s a working rule of adulthood. So do Jews want to love themselves? Fine, but it has to be a conditional love.”

I wonder if Wieseltier thinks anti-Semitism has, in part, been born of that perceived smugness and what he labels self-love?

“No. I don’t think that one seeks the cause of anti-Semitism in anything that Jews are like or not like. I think that’s a basic mistake. I think if you want to understand anti-Semitism, you study the non-Jews, not the Jews. If you want to understand racism, you study whites, not blacks. The idea that you study Jews or blacks is itself an expression of prejudice.”

But he must have encountered Jews—most of us have—who felt ashamed of other Jews.

“I know. I understand it psychologically, though of course I don’t take kindly to it (except in certain cases: We have our villains, too). It has to do with immigrant communities, it has to do with the memory of immigrant parents. There was a writer in New York in the 1950s called Harvey Swados. He has a story—you should find it; it’s so painful—about a young Jewish man whose father is a peddler and has a pushcart on the Lower East Side. I forget the story exactly, but the young man finally convinces this really swell chick from a well-to-do Jewish family to go out with him; and they have dinner and it’s all fine, and they go for a walk, and suddenly, to his increasing horror, the young man sees that at the end of the street where they’re walking is his father with his pushcart. And he doesn’t know what he’s going to do. And when they get to the pushcart, he walks right by his father and doesn’t acknowledge him. It’s excruciating to read. But I understand it psychologically; status anxiety is not an exclusively Jewish phenomenon. The status anxiety of the children of immigrants we know a lot about. The Muslim communities in America are about to start experiencing this, and good luck to them.”

This reminds me that he was married to a Muslim—a Pakistani woman—for eight years; not an obvious match for someone whose Judaism has been so central. For the last three years, he has been married to a Catholic woman, Jennifer. “My wife’s a convert,” he explains. “Orthodox. The advanced degree. Often I’m envious of converts because they made a decision; the rest of us were just born Jewish. A lucky accident, a lucky honor. But when you make a decision, you must have reasons, and when you think about your reasons, they deepen. Kierkegaard somewhere said that it is harder for a Christian to become a Christian than for a non-Christian to become a Christian. The same may be said of Jews.”

So, despite what he describes as his “erotic relationship with Judaism,” he never married a Jew?

“No. Jennifer converted. So I guess I never did.” Isn’t that surprising? “Well, my mother once said, ‘Don’t you feel that you have to marry a Jewish woman?’ and without being at all ironic and without missing a beat, I looked at her and said, ‘If I hadn’t been given the finest Jewish education in the world, I might have had to marry a Jewish woman.’ I don’t need anyone to be Jewish with, and I have no interest in making love to myself, if you see what I mean. I don’t need two of everything. And so I tell all my Jewish friends looking for love and marriage, ‘If you can’t find a Jew, make a Jew.’ I mean, it’s a big, wide world. Conversion is a very beautiful thing. And I take personal freedom and democratic life very seriously. (Anyway, I never hold myself up as a model of how to live.) It happens that you fall in love with someone you’re not ‘supposed’ to marry. That’s called living in an open society. I understand why the Jewish community and the Jewish tradition want me not to marry such a person, and when I married such a person, I never told my parents that I was right. I always said to them that I recognized that by the standard of our tradition, of our law, I was wrong. But that is not the only standard by which a rational and democratic person lives. So what was by their lights a betrayal was by my lights a collision of principles. It’s a very complicated thing.”

But he didn’t fret about it?

“No. I didn’t fret about it because if I was the only Jew on the planet, Judaism would still survive. I mean, it would survive as long as I survived. And any child I would have made would have been taught to know Jewish words and ideas and customs well. I don’t have any doubt about my competence as a Jew. I have a princely confidence as a Jew. This is not vanity—I know how much I don’t know and I know who knows a lot more than I do and I know where they are and I ask them questions all the time. But I took the trouble of acquiring the knowledge I would require to live thickly as a Jew in the entirety of my tradition. And I do so not least because I wanted to acquire this confidence, this authority.”

And his and Jennifer’s plans for this new Wieseltier?

“He will go to a Jewish day school. No question about it. Many years ago a wise and lively man, a liberal judge in Boston named Charles Wyzanski Jr., remarked to me over a lot of brandy that the only people who have freedom in matters religious are people who were indoctrinated in one as a child. And I think he’s right. So I want my son to be completely fluent in Hebrew, in Judaism. And when he grows up he can decide for himself what he believes and how he wishes to live. If he leaves, it won’t be ignorantly. If he stays, it won’t be dilettantishly.”

Talking about Wieseltier’s parenting, I wonder about his father; it struck me, as I finished Kaddish, that I had little grasp of who his father was. “That’s right,” he says with a nod. “I wasn’t writing a memoir. And it’s none of my reader’s business who my father was.” But wasn’t it part of the process of saying kaddish—to reflect on his father and their relationship? “It was to a certain extent, but that’s not something that would be of interest to other people as far as I’m concerned. That strikes me as a private matter. And again, one of the reasons I wanted my readers to know almost nothing about my father is that I did not want my religious life to be reduced to my filial life. That’s why I did no promotion for the book. No book tour, no radio, no author’s photograph, no blurbs; nothing, nada, niente . My publishers thought I was mad. But I said to them that I did not want to travel the land being asked psychological or soap-operatic questions about a father and a son. I was writing about religion and philosophy and life and death, not about Mark Wieseltier and Leon Wieseltier. There had to be enough about me as a son to make it clear that all these texts of mourning were being lived and not just studied. But not so much that the study of mourning in Judaism could be reduced to this son’s experience of it. It was tricky.”

If he doesn’t want to tell me about his father, can he at least tell me whether the year spent saying kaddish for him was a kind of reckoning? “Of course it was. And the reckoning I made with him turned out to be unexpectedly free and candid precisely because I was doing my duty. I squandered no energy on guilt or delinquence. I simply made myself into an instrument of my obligations and proceeded to think my thoughts. My thoughts about my tradition I recorded; my thoughts about my father I did not.”

Does he concede that those few times in the book where he describes his father as difficult do beg the question of what this man was to him? “Sure, but discretion is a large part of dignity. It is perfectly clear in my book that the author loved his father and was wounded by the death of his father. Also that he was a Polish Jew who came to the States after the war, the sort now known as a Holocaust survivor, and a troublesome man. That seemed enough.”

I ask him to flesh out the story he tells in the book about the time a friend of the family offered to say kaddish for his father in his place. “I just went to that man’s funeral,” Wieseltier says with a dose of irony. Why did this man make that offer to be his surrogate? “Because he didn’t trust me,” Wieseltier answers. “Because I was heterodox in many ways and the family knew it. And you know, the kaddish, like a lot of contemporary Orthodoxy, has been absorbed into a folk-religious view of things, and so basically he was worried about the fate of my father’s soul and so the kaddish, three times a day, was absolutely essential to get my father a good verdict.”

In the book, Wieseltier is less sanguine about the incident: “I was furious,” he writes. “I do not deny that I live undevoutly, or that the fulfillment of this obligation will be arduous for me. But it is my obligation. Only I can fulfill it.”

This responsibility clearly brought him back to the fold, so to speak. “I was a pariah until I became a mourner,” he writes. “Then I was faced with a duty that I refused to shirk, and I was brought near.”

I remind him of another passage: “All my life I went to shul with my father, that is, I went to shul as a son. It was because I found it almost impossible to stop going to shul as a son that I stopped going to shul. I came to conflate religion with childhood. But childhood is over.” It’s the notion we discussed earlier, of leaving the childhood “trauma” of Jewish indoctrination behind and reclaiming it. “I wanted to be a Jew on my own,” Wieseltier emphasizes. “I didn’t want to be just an heir. I knew that I was an heir and in my ways I lived all my life as an heir; but I wanted to be an autonomous individual as a Jew also. And then I could consent again to being an heir. If you’re just an heir, then you’re still a child, merely a son, forever a passive receptacle. I wanted to be an active receptacle. And so I had to break out of the tyranny of the family over my spiritual and intellectual life. And out of the tyranny of the people and its politics, too. On some level I keep my Jewishness private from other Jews as well; I don’t want them to ruin it either.”

I personally relate to this idea of one’s religion being tied up in—and muddied by—family expectations or obligations. I read Wieseltier his line, “Religion is not the work of guilty or sentimental children.” He nods. “Look, in the matter of religion Freud was philosophically wrong and empirically right. He was philosophically wrong that religion is simply an expression of reverence for the father. It is not—which is one of the reasons I’ve never liked the concept of God the Father, the way I don’t like God the King. One has to be very careful about the metaphors that one imports into one’s beliefs about the world. But he was empirically right in that for most people religion is simply an enlargement of their attitude towards their parents. And that’s a terrible thing. It means in the matter of religion most people are permanently children. And so religious life to them becomes a process of endless re-infantilization. Over and over again. It’s insulting to the soul.

“Religion is about the fate of every individual soul. Religion is not even primarily a collective thing. The practices, the rituals, the gathering— that’s for the people, that’s for the family. But family life is not the same thing as spiritual life. (And often it’s the polar opposite.)”

I tell him that, for many of the people I’ve interviewed—not to mention many people close to me—religion is primarily about family. “That’s because people cannot disassociate their religious life from their parents because they think that being religious is a way of being good little boys and girls. And of compensating for the distance that they’ve traveled from their origins, of making up for all the other ways in their life where they refuse to be good little boys and girls. It’s the peace offering that they bring to their living or dead ancestors. And they are encouraged in this reduced sense of religion by many Jewish institutions, which give the impression that all that matters to Judaism is the children. But Judaism is not for children. I mean, there are children who have to be raised as Jews, but this is not essentially about the children. This is about the spiritual existence of mature souls and moral agents.”

Wieseltier gets a phone call from his wife: She wants to know if he’s ready for her to swing by and pick him up at the office. Before he goes, I want to know what Wieseltier would advise someone if they came to him asking what it means today to be Jewish. “The one-word answer is ‘Judaism,’” he says. “That’s the only answer there is or ever will be. Everything else is a corollary of that. I mean, the Jews are a people, the Jews are a nation, the Jews are a civilization—but they’re all of that because they are first and foremost a religion. That’s the source of the whole blessed thing. Except for our religion, we would not be a people. When Jews come to me with perplexities about the meaning of Jewishness, I say to them: Judaism. Just go to it; check it out, study this, study that, try this, try that, humble yourself for a while before it, insist upon the importance of having a worldview, develop reasons for what you like and what you don’t like, get into the fight. Get into the fight. That’s the one-word answer: Judaism.”