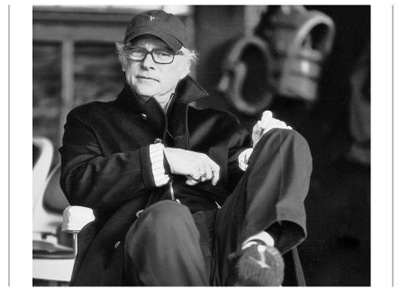

Barry Levinson

BARRY LEVINSON PHOTOGRAPHED BY YVONNE FERRIS

BARRY LEVINSON, the director of Diner, Rainman, Good Morning, Vietnam , and Wag the Dog, is unshaven in sweatpants, sitting in his gracefully designed home office on his Connecticut estate, talking about his 1999 film, Liberty Heights. “Jews, gentiles, and Colored People,” Levinson pronounces. “That’s what I wanted to call Liberty Heights. The studio had a fit: ‘No! My God, are you kidding?’ I said, ‘Why not? That’s who it’s about.’ In the end, it was decided it was too inflammatory. I had thought, ‘At least the title will jump out at you.’”

The semiautobiographical 1999 film chronicled a middle-class Jewish family, the Kurtzmans, in suburban Baltimore. Joe Mantegna is the family man who each year on Yom Kippur skips out of services to go to the Cadillac showroom and view the new model; Adrien Brody plays his older son, who becomes obsessed with the typical shiksa goddess—played by model Carolyn Murphy; and Ben Foster is the younger brother, Ben, who falls for a smart, attractive black classmate.

Early on in the film, there is this exchange between Ben and his buddy, Sheldon, as they discuss the sign at the local pool that says “NO JEWS, DOGS, OR COLOREDS ALLOWED”:

BEN: How do you think they decided the order?

SHELDON: What?

BEN: That Jews should be first.

SHELDON: Yeah. I would have thought it would have been “Dogs, Coloreds, Jews.”

BEN: That must have been some meeting to come up with that. Someone had to say, “No, I have to tell you, the Jews bother me more than the dogs.”

Levinson, sixty-three, believes to this day that the explicit Jewishness of his script gave Jewish studio executives the jitters. “The reality is that anytime you do a movie where there are Jewish people in it, there is always going to be this situation where they’ll think, ‘Well, it’s too Jewish; no one’s going to understand it, no one’s going to like it. I can love it—I’m Jewish—but no one else will’—that kind of sensibility. Which may be part of the inferiority complex of a Jew who thinks no one can understand them except them.

“Studio people are petrified. When I did Avalon [his 1990 film about a Jewish family striving to assimilate], they thought, ‘Only a Jewish person could enjoy this movie.’ The reality is that, over the years, I get letters from Japanese, blacks, Norwegians who say, ‘That was just like my family.’ That’s the amazing thing about film or literature—people can make connections. But when you do these projects, not only do you gamble, but you sort of take your artistic life in your own hands. Because it’s a very difficult road to go down. Very.

“Studios are afraid to distribute it; they don’t advertise it the same way. It’s fraught with a lot of danger zones. Film at the end of the day is a commercial business; they look for the most commercial work to do. Therefore, when you get into certain kinds of movies, they’re very nervous about it. It’s one thing when you have a certain violence to it; then you can increase your commercial viability.”

In other words, if he had scripted some Jews getting killed? “Yes!” Levinson smiles. “If you don’t do that, then it’s just ‘Jews.’ It’s interesting that ultimately the most successful movies about Jews are really about dead Jews and not Jews that live and laugh and everything else; because then they’re ‘just Jewish.’ But dead Jews: Then it’s significant. Anytime you do the rest, it’s ‘Well, they’re too Jewish.’ Have you ever heard the comment ‘They’re too Italian’? Do you ever hear ‘It was good, but I thought they were too Catholic’? You can only be ‘too Jewish.’”

I wonder if he’s ever worried that he’ll be pegged as a Jewish director. “I don’t think you can worry,” he replies. “You are what you are. But it’s true that, in the world we live in, to be considered a Jewish director is not a great thing to be. That doesn’t have great cachet to it.”

Why does he say that? “Because I think the way the business views things, that is not important enough.”

Levinson obviously decided to proceed on Liberty Heights regardless of the skepticism. “There are some ideas that just propel you,” he explains. “So you’re going to fight studios and fight distribution and ultimately you may end up with a film that may not have the same commercial viability. But you do it because you believe in the work.”

The idea for Liberty Heights was sparked when Levinson read a critic’s review of his 1998 science fiction movie, Sphere. Lisa Schwarzbaum of Entertainment Weekly called Dustin Hoffman’s character a “Jewish psychologist” when his ethnicity was nowhere in the script. Schwarzbaum wrote, “Okay, so he’s not officially Jewish; he’s only Ho fman, who arrives at the floating habitat and immediately announces, noodgey and menschlike, ‘I’d like to call my family.’ You do the math.”

“It jarred me for a number of reasons,” Levinson says, putting a leg up on a coffee table piled with scripts. “I don’t know her at all; I assume she’s Jewish with that name. But the reference that she made, implying that we were either hiding the fact that he was Jewish or that he wants to call home like a nice Jewish boy, I just thought was kind of weird. And some people might say that’s an overreaction, but I was thinking about it: I mean, no one would mention that someone is a Protestant in a review. It stayed in my head. And I began to think, ‘What is this whole thing about Jews? Why do we somehow have to define who’s who and what’s the point of it?’ I suddenly started to write and there it was. At the end of it, I wanted to be able to show the absurdity, the nonsense of prejudice. And also to show that it wasn’t really based on hatred.”

The film was not a great success. “To me it was very disappointing,” Levinson says, “because we got great reviews, but the studio was petrified of a movie that was going to deal with those issues.” He seems bitter that Warner Bros. didn’t promote the film. “They didn’t bother,” he says.

Like so many others in this book, Levinson remembers despising Hebrew school—“I might as well have been on Mars for two hours.” His Jewishness is found in the milieu of his movies more than in any spiritual identification. “It is what I am, you know? It’s a sense of a big extended family—the traditions when so many of us gathered. And it is made up of the stories of being in Russia or Poland or Latvia—that journey to America. That’s where my connection is. How important is it? I don’t know. But it affects everything that I do in some way, unconsciously or consciously. Mostly unconsciously.”

In Liberty Heights, for example, it can be found in the character of the father, Nate Kurtzman, who, like Levinson’s own father, Irv, checks out the new Cadillac every Yom Kippur; or the character of sixteen-year-old Ben, who, inspired by Levinson’s real cousin Eddie, dresses up as Hitler one Halloween and is forbidden to leave the house. Or the character of Grandma Rose, who always stays on the telephone after she’s answered it, even when it’s not for her. “Hang up!” her grandson yells.

Levinson idealizes the gentile girl in the film just the way he and his friends did as kids: “In the script, I alluded to Lewis and Clark: ‘We found the Northwest Passage and there were all these blond-haired girls and they were all great-looking and they had names that sounded terrific and we thought we’d found the Promised Land.’”

He says when he dated non-Jewish girls as a teenager, they shared one trait in common: They were prompt. “We would go to pick up gentile girls at their houses and we always remarked, ‘They’re so punctual! You ring their bell, they’re ready to go!’ But it never occurred to us what that was really about: They wanted to get out of the house before we had a chance to come in and meet the mother and father and say, ‘Hi, I’m Barry Levinson .’ We were thinking the girls were so punctual, when really it was about the fact that they’d otherwise have to introduce this Jewish boy to their Protestant or Catholic family.” Levinson says his parents didn’t weigh in on whom he should date or marry. “Didn’t come up,” he says. “My grandmother on the Levinson side was much more religious—she kept kosher—but she said something to me before she died which was extraordinary: ‘A Jewish girl, it doesn’t matter. You should find someone to make you happy.’”

He did. Diana Rhodes, Levinson’s second wife, is a painter and a non-observant Catholic. Their two sons, Sam and Jack, have taken opposite religious paths. “Jack studied and is going to be bar mitzvah and Sam, on the other hand, had no interest in it,” Levinson says. His stepdaughter, Michelle, who came into his life when she was seven, decided as an adult to convert to Judaism. “So we’ve got a family that’s all mixed up,” he says with a chuckle.

Levinson wrote a line for Liberty Heights that captures how he has tried to revisit—or revivify—the atmosphere of his Jewish childhood. The character Ben Foster says at the end of the film, “Life is made up of a few big moments and a lot of little ones . . . but a lot of images fade, and no matter how hard I try, I can’t get them back . . . If I knew things would no longer be, I would’ve tried to remember better.”