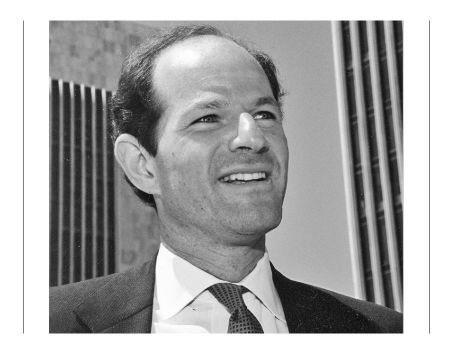

Eliot Spitzer

ELIOT SPITZER, whom the New York Times has called “the most prominent Attorney General around,” who is gearing up to declare his candidacy for New York governor when I meet him, is in his Manhattan office during a snowstorm, looking immaculate in a blue suit, white shirt, and black shiny shoes. Of course, he’s at his desk in a blizzard. Article after article has been written about Spitzer’s ambition and tenacity, his trophy diplomas from Horace Mann (tennis team captain), Princeton (student body chairman), and Harvard Law School (Law Review); his election at age thirty-nine—in 1998—to the office of New York State attorney general, and lately, his headlines for taking on corruption in the financial and insurance industries. He’s been touted for rousing a tired office into becoming an aggressive muckraker.

As for Spitzer’s Jewishness, he says it can be found in his work. “On one level it pervades everything that I do,” he says, sitting on a government-issue blue chair on a government-issue blue carpet. “I’m always trying to figure out what is the best way to use the capacity of this office to do something that’s useful. And it’s not as though one’s deepest values pervade every decision like that, but to a certain extent, when I’m thinking about, ‘Do I want to get involved in this issue, and if so, why, and whom do we help,’ to a certain extent that does go back to my sense of what the core values of Judaism are as I understood them. I do have a sense that when I set priorities and try to articulate what it is we’re doing, the reasoning stems concretely from my Jewish ancestry, as my dad conveyed it to me.”

His father, Bernard Spitzer, a civil engineer who became enormously wealthy in real estate, instilled his son’s hustle and acumen. (Spitzer describes his relationship with his mother—a literature professor at Mary-mount Manhattan College—as “the classic son-mom type,” saying “She is just as intellectually acute, but was always more emotionally driven.”) Family dinners in Riverdale, New York, were a place for discussion and debate: The three children took turns bringing an issue to the table. (They were also quizzed on sightseeing during family vacations.)

When I ask Spitzer how he would link Jewish values to achievement, he laughs: “I’m neurotic.” He confesses that he’s inherited his parents’ premium on accomplishment. “I’m not necessarily comfortable with self-analytical stuff, but it’s hard, I suppose, to deny that when I was growing up, there wasn’t a certain set of expectations, or that I haven’t passed that on to my eldest daughter at this point. My younger two are still a little young—but even my eight-year-old, who is in third grade, hasn’t missed a spelling word on her weekly spelling test all year. There is a very real sense that we expect performance—always shrouded, of course, in the cliché that ‘We want you to do the best you can do.’”

The academic pressure with which he was raised and is raising his own children, however, does not apply to his Judaism. Spitzer’s parents, despite Bernard’s training as a cantor (“He has a great voice,” Spitzer says), did not take him to synagogue regularly or insist he be bar mitzvah, which his mother still regrets. “Once or twice she has voiced misgivings that I wasn’t bar mitzvahed,” Spitzer says, “but when I ask her why, it sort of doesn’t go anywhere. So I don’t know quite what to make of it.” It’s clear that Spitzer too feels ambivalent. “There are moments where I wish I’d had a more formalistic training. One thing that I think is symbolic of how my dad viewed it was that instead of my being bar mitzvahed, he wanted me to read Abba Eban’s History of the Jews. That gives you a certain insight into what he considered the important aspect of the maturation process. And if my children are not bat mitzvahed, they’re going to read that book, too. Because I think understanding the history and the cultural predicates of Judaism is critically important.”

Spitzer’s own religious parenting has been complicated by the fact that he married Silda Wall—a law school classmate—in 1987: “She’s not Jewish,” he says, “which is an issue that we’ve grappled with in terms of the kids.” (They have three daughters ranging from ten to fifteen years old at the time we meet.) “I obviously feel that the children will be Jewish; they’re going to Horace Mann—a school that’s predominantly Jewish, they’re growing up in a Jewish environment, a Jewish culture.” I ask if he and his wife discussed the matter of religion before they got married. “Yeah,” he says with a smile. “You know how conversations like that go. To put it in the context of a corporate transaction, it probably wasn’t the deal-breaker on either side, so it sort of got pushed aside and we delayed. Even the closing documents didn’t address it.” So, the hurdles are being dealt with as they go along? “Yes.”

He says the girls go to church only when they visit his in-laws in North Carolina. I ask if that makes him—“flinch?” he finishes my question. “I grimace. But I bear it.” He seems to take comfort in the fact that at home, they’re surrounded by other Jews. “My view is they’re here in New York and they’re growing up in a culture that is essentially a transmission to them of Jewish values. I want to take them to Israel. I don’t know when I will. I’ve resisted going on all the political junkets; I don’t want to be there with ten elected officials. I think that would cheapen it.”

I wonder if he thinks his children consider themselves Jewish. “I hope—” He pauses. “They probably consider themselves confused, but that’s like all kids. I think they are very conscious of the fact that they are Jewish, but Mommy might not be, but that’s okay.” All three daughters attend Hebrew school, but one has already taken her father’s path. “My eldest is not being bat mitzvahed. The younger two, it remains to be seen.” I asked if it was his daughter’s decision. “As parents, there are choices that you lead your children to; this one I really had a more hands-off attitude because I didn’t want to force it on her because I didn’t think that would be terribly productive.”

In addition to celebrating Hanukkah, the Spitzers do have a Christmas tree every year. He says he doesn’t recall his parents ever cringing at the sight. “They know that nothing I’m doing is a rejection of how they raised me—which I think would evoke a different emotional response from a parent. If they had been much more rigorous in their purely religious training with me and I had gone somewhere else on the spectrum, that might have been difficult. But what we’re doing is very much in sync with where they were.”

Even without the religious foundation, Spitzer says ethnic pride fuels his professional focus on fair treatment. “We have been able to represent immigrant groups who came here—West Africans, Mexicans, Asians— who have been taken advantage of by a system where they were denied rights because they were easy targets. We are a nation of immigrants, very much like Jews in the Diaspora, who have needed to migrate, to find a home. That sense of providing opportunity is what America is all about. It’s the common theme that I hope traces through much of what we do.”

He confesses there have been moments where his Jewish pride has been tested. “I wouldn’t be truthful if I didn’t say that occasionally there have been a couple cases where the defendants were Orthodox Jews. There was a high-profile fraud case, for example, and within a certain circle of the Orthodox community, there was a lot of anger against me. People said, ‘What are you, one of those Jew-hating Jews?’ This defendant was someone who had given away a lot of money to the community, but he’d stolen the money he was giving. At the end of the day he pled guilty to every count of the indictment; the evidence was that overwhelming. So I went back to the people who had come to me and who had said things that hurt. I never let on that it hurt, but it hurt because I felt it was not only unfair but it was wrong, and it was wrong for them as Jews to think in that way. It bothered me. I looked them in the eye and I said, ‘Now you understand: you were wrong. At least I hope you do, because it was the wrong way to judge me and it’s bad for us as Jews when we react that way.’”

I’m talking to Spitzer before the 2004 election and before his subsequent announcement that he’s running for governor of New York. He won’t comment on whether he dreams of the presidency, as some— including his father—have speculated, but he does say it’s “stupendous” that Senator Joseph Lieberman could be taken seriously as a candidate without his religion being the focal point. He also gets a kick out of revelations that Senator John Kerry has Jewish blood. “Next time I see him, I’ll say, ‘Hey! We’re closer than we thought.’”