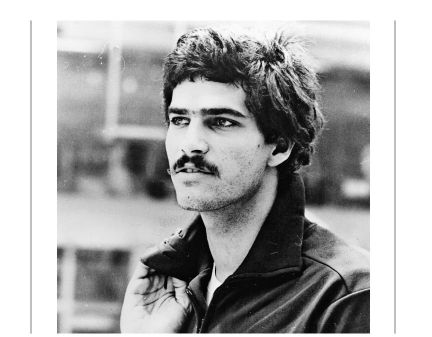

Mark Spitz

A. B. DUFFY/HULTON ARCHIVE/GETTY IMAGES

MARK SPITZ WAS THE FIRST, and remains the only, Olympic athlete to win seven gold medals in one year—1972—each one breaking a world record. The fact that this champion swimmer was Jewish and triumphed in Munich, Germany—forty-five minutes from Dachau—was history-making enough. But tragic events made it even more poignant: The same night he won his seventh prize, nine Israeli athletes were taken hostage by Palestinian gunmen, who killed them the following day.

“I was a Jewish swimmer at the Munich Olympic Games,” Spitz recounts by phone from his Los Angeles home. “We were fifteen miles from Dachau, and here was this Jew at the games. It’s important to remember that 1972 was the coming-out party for Germany; the nation was saying, ‘We’re here and we’re not like the regimes of thirty years before. These games will be the perfect example that the German people have come full circle.’ And then I go and win seven gold medals. And that night, the terrorists jump the fence and later kill eleven Israeli athletes. So there was simultaneously the triumph of my accomplishment and the tragedy of the Israelis; these two were inextricably linked.”

The day after Spitz’s gold sweep was September 5, 1972, and Spitz, then twenty-two, was supposed to be at a press conference talking about his feat. Instead he was rushed out of the country because law enforcement feared he might be in danger. “I left that evening because of the ensuing uncertainty of what was going on,” says Spitz. “I woke up in London—I was with my swim coach—and read about the killings in the paper. It was unbelievable.”

He says the symbolism of these events only intensified the public focus on his religion. “My being a Jew was put into the limelight in a very big way,” says Spitz. “I had a calling of the guard to step up to the plate and recognize that I was Jewish.”

Not only were journalists and Jewish groups bombarding him; Spitz says even the president was preoccupied with his affiliation. Recently released tapes of Richard Nixon’s conversations, publicized in December 2003, show that Nixon deliberated over whether to make a congratulatory call to Spitz. “There was a quote from Haldeman talking to Nixon,” says Spitz. “It was about how Nixon painstakingly vacillated about whether to call Mark Spitz after he won seven gold medals but elected not to do so. Do you know why? He assumed, because most Jews are Democrats, that I supported George McGovern. This was September of 1972—two months before the election—and he didn’t want to align himself with Democrats by congratulating a Jewish athlete because Spitz was probably a Democrat,” Spitz says with a chuckle. “The irony is that I’ve been a registered Republican since I’ve been able to vote.”

Spitz, fifty-five, grew up in California and Hawaii—where his father, Arnold Spitz, put his son in the water at age two. “I was bar mitzvahed on December 7, 1963, the anniversary of Pearl Harbor,” says Spitz. “I was very nervous that day, but there were only two people who knew I made a mistake during the service. I remember that because I was embarrassed. In my haftarah portion, I chanted one line twice. Only my grandfather and the rabbi knew that.”

He started competitive swimming before he was ten and was named the world’s best ten-and-under swimmer. At fifteen, in 1965, he went to Tel Aviv for the Maccabiah Games—an annual contest created to celebrate and encourage Jewish young people in sports—and he won four gold medals. A year later, Spitz went to compete in Germany. I ask him if it felt strange to be there as a Jew. “In 1966 I was sixteen and the war had only been over for twenty years,” Spitz says. “The thought did occur to me that anyone I met in their forties could have been a Nazi at one time. It was weird to walk into a bakery and know that, twenty-odd years ago, I would have been pulled into the street and shot . . .” He pauses. “Of course your humor about that situation is a lot different when you’re sixteen or seventeen because nothing happens to a seventeen-year-old.”

Years later, in 1985, Spitz was asked to return to the Maccabiah Games to carry the torch. “There were three little girls, thirteen years old, who ran behind me,” he recalls. “Each of those little girls’ mothers was pregnant when I was in Munich. Each of their fathers was killed as one of the Israeli athletes. That was pretty emotional.” Spitz is quiet for a moment. “That was the best time for being a Jew.”

But Spitz says his status as a Jewish role model never fueled his athleticism. “I embraced the fact that I’m Jewish. Did that have an influence on me athletically? Zero. Does it influence younger people? Yes. Because it says that being a Jew is not something that limits you physically and athletically.”

I ask him why he thinks there are so few Jewish sports stars. “There are fewer sports stars only because there are fewer Jews,” he scoffs. “We have the same number of Jewish athletes proportionately as non-Jews have. Does that mean that Catholics are better than us? Hell no. It’s just sheer numbers.”

What about the stereotype that Jews go on to be doctors and lawyers, that they favor more intellectual pursuits? “That’s not because we’re smarter,” says Spitz. “If you keep telling your kids to hit the books, even a dummy can get smarter.”

Spitz himself was preparing to go to dental school before he abandoned that plan after the 1972 Olympics. These days, Spitz works as a stock broker and financial analyst and gives inspirational speeches. He’s been married to “a Jewish girl,” as he puts it—Suzy Weiner—for thirty-two years. “Early on, before I even got married, I thought about how I would raise children if I were to marry outside the religion. How would they identify with who they are and would it be good to have a split situation, where they were raised with both religions involved? I realized that that wasn’t something I would be comfortable doing. So perhaps it’s prejudiced, but I focused on marrying someone Jewish.”

Both his sons—Matthew, twenty-four, and Justin, fourteen—went to Stephen Wise religious school starting from kindergarten and became bar mitzvah. “The funny thing is that it becomes kind of contagious,” says Spitz. “When you’re around a community that embraces religion, you embrace it more, too. I’ve been participating in this in a big way. I’m a big proponent now. I used to hate going to High Holy Days services; as soon as I got there, I was counting the minutes till I could leave. Now I look forward to going. Maybe I’m older and not as fast paced as before. Also, I’m an example for my kids. I enjoy it.”

Though he never experienced any overt anti-Semitism, he’s still bothered by the fact that he was not asked to participate in the opening Olympic ceremonies in either 1984 or 1996. “Look, one of the greatest honors bestowed upon someone in the Olympic games is that at the opening ceremonies they honor past notable Olympians and their accomplishments—not just the medals they won but the way they’ve represented their sport. These athletes would participate in the opening ceremonies, either running the torch, lighting the cauldron, or carrying in the Olympic flag. In the Olympic games in L.A. in 1984, I was thirty-four. They had two people involved in carrying the torch—both of them deserving as far as their credibility and athletic accomplishments. But Mark Spitz wasn’t there.

“In the 1996 Olympic games, there were three people involved in the opening ceremonies and the lighting of the torch. And in no cases were any of them Jewish. I guess Mark Spitz didn’t win enough medals to be included in that fraternity. I leave it to you to figure out why. Does it bother me? Would I have liked to? Sure. I didn’t compete in the Olympic games just to win medals, become known as a Jew, and then be asked to run in the Olympic flame; I did it because I love the sport. But I noticed.

“But hey, I’m still not dead,” he adds. “There’s still a chance.”