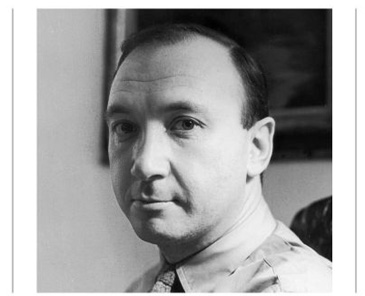

Neil Simon

NEIL SIMON PHOTOGRAPHED IN 1970 BY JILL KREMENTZ

MARVIN NEIL SIMON ONCE WROTE that he dropped his first name when he realized that “Marvin Simon” would never “be announced on the public address system at Yankee Stadium as playing center field for the injured Joe DiMaggio.” In a phone interview from Los Angeles, he says he did not grow up in “what you would call a really Jewish home.” His parents kept separate dishes for the High Holy Days and tore off pieces of toilet paper before the Sabbath arrived, so they wouldn’t have to “work” on the day of rest. That was about the extent of it. “They ate the right food,” he adds.

Simon soured on religious education when he was chastised for asking what he thought was a reasonable question in Hebrew school. “The rabbi was telling us about Adam and Eve and their children, Cain and Abel,” Simon recalls. “He said Cain slew Abel and then went out into the world and wherever he went, people shunned him. And I said, ‘What people? You just told us they were the only human beings on earth.’ The rabbi said, ‘Shut up.’” Simon pauses. “Things like that are what discourage you from having a religious background.”

He also disliked that the subject Hebrew school seemed to care most about was tuition. “The rabbi would say to me, ‘You got the money? Did you give us the money yet?’ It’s very possible and probable that the place I went to in Washington Heights was not a very good place of learning.”

Simon also found observance too demanding. “I think one of the things that put me off a little bit was the amount of time you had to spend to be a good Jew,” he says. “The amount of times you had to go to synagogue.” His older brother, Danny, went more often. “He had more fear of it,” Simon recalls. “My brother would sleep next to me and I remember hearing him at night praying, ‘Please, Jewish God, give me this; please, God, give me that.’ I thought it was interesting because I said, ‘Look; he’s making selections.’”

In Simon’s memoir, Rewrites, he recounts the family’s annual visit to shul on the High Holy Days and how his father insisted he recite the prayers in Hebrew. “I would say, ‘I don’t know what the Hebrew means.’ He answered, ‘Do what I say. God doesn’t understand English.’”

Simon, seventy-seven when we speak, says the anti-Semitism he saw in his Bronx neighborhood—“there were always street fights”—paled by contrast to his later stint in the army. “In the army, I knew that I was Jewish because they would tell me so,” he says. “That was when I really got it. It struck me as being so hypocritical and kind of stupid that the guys who were the cooks—who were to me the dumbest group of all the guys that I met—were putting us all down for being Jewish.”

In Biloxi Blues, the third of Simon’s autobiographical trilogy about a Brooklyn Jewish family, the main character, Eugene Jerome (played on Broadway by Matthew Broderick), goes to boot camp and learns that the same American soldiers who are champing at the bit to kill Nazis also happen to hate Jews. When the character Joseph Wykowski ridicules Eugene’s fellow private, Arnold Epstein, Eugene does nothing. “I never liked Wykowski much and I didn’t like him any better after tonight,” Eugene confides to the audience. “But the one I hated most was myself because I didn’t stand up for Epstein, a fellow Jew.”

This Pulitzer Prize–winning playwright—with more than thirty plays and twenty films to his credit, including Barefoot in the Park, The Odd Couple, The Sunshine Boys, The Goodbye Girl, and Brighton Beach Memoirs— chose to re-create one of his first comedy-writing jobs in his script for Laughter on the 23rd Floor. It was based on the writing team of Sid Caesar’s Your Show of Shows, which included Simon, Carl Reiner, Larry Gelbart (who later created M*A*S*H), Mel Brooks, and Caesar himself. “Almost all of them were Jewish,” he says. “It was just familiar and it made things easier. There would be things that were very funny that were said in the room that would come from a place familiar to us all. If a guy came from Ohio, it would be hard for him to catch up.”

He sounds annoyed when I ask him if he thinks American humor has been shaped in large part by Jewish humor because so many comedians are Jewish. “I have such a hard time talking about this and my answers are always the same,” Simon replies. “Even having difficulty talking about it says something about what my background was like.”

But Simon has often been described as a Jewish playwright. “I always felt that people were trying to pinpoint clues and say, ‘Is this a Jewish play?’ and I never thought of that. Even though I thought my characters were sometimes probably Jewish. Barefoot wasn’t Jewish. Come Blow Your Horn was.” I ask if he’s bothered when critics or commentators analyze the Jewishness of his work. “It only bothers me in that not all the plays are about that,” Simon answers.

He also resists speaking about his personal life. It’s well known that he was deeply distraught when his first wife, Joan Baim, died of cancer in 1973 after almost twenty years of marriage, leaving their two daughters, Nancy and Ellen. In his memoir, he writes about his helplessness watching his wife slip away. “I looked for the God I hoped existed but was too cynical to believe in. It did not, however, stop me from asking Him to point me in the right direction, as I mumbled silent prayers on the carpet of my office in the late-night hours when Joan was asleep.”

When I ask him whether his daughters feel Jewish, he says, “The youngest one—who’s now forty—started to look into it for herself in college and went to synagogue for a long time to see what she could get out of it. She wouldn’t talk to me about it much; she just felt that maybe she’d missed something.”

I can tell that Simon is ready to get off the phone. When I ask my last question—how much it matters to him to be Jewish—I assume he’ll brush me off; but his answer surprises me. “It matters to me like my hands matter to me,” Simon replies. “It’s there.”