Dragon Professional Individual gives you two methods to move the mouse pointer. “MouseGrid” breaks up the screen (or the active window) into a series of squares, letting you zero in on the location you want to move the pointer to. The mouse pointer commands let you make small adjustments by saying things like, “Mouse Up Five.”

How does it work? Surprisingly well, after you get used to it. Naturally, you have to adjust your expectations: Voice commands are not a high-performance way to move the mouse, so you won’t break any speed records the next time you play a game. But your virtual, voice-commanded mouse, like the physical mouse attached to your computer, is remarkably intuitive. It makes a good backup system for those times when you can’t remember the right hotkey or voice command.

Making your move with MouseGrid

In days of yore, before the invention of GameBoy, children amused themselves on long driving trips with number-guessing games. Here’s a simple one: One kid picks a number and another makes guesses. The number-picker responds to each guess by saying “higher” or “lower.” The guesser narrows down the range where the number can be until eventually he knows what the number is.

“MouseGrid” is like that, but in two dimensions. You pick a point on the screen where you want the mouse pointer to go, and Dragon Professional Individual guesses where it is. Start the game by saying, “MouseGrid.”

The MouseGrid is not supported in Windows 8 Modern UI.

The MouseGrid is not supported in Windows 8 Modern UI.

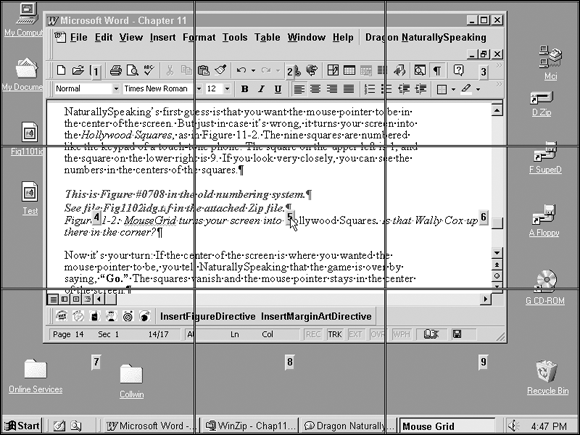

Dragon Professional Individual’s first guess is that you want the mouse pointer to be in the center of the screen. But just in case it’s wrong, it turns your screen into a tick-tack-toe board, as in Figure 15-3. The nine squares are numbered like the keypad of a touch-tone phone: The square on the upper left is 1, and the square on the lower right is 9. The pointer is sitting on square 5. Look closely to see the numbers in the centers of the squares.

Now it’s your turn: If you want the mouse pointer in the center of the screen, tell Dragon Professional Individual that the game is over by saying, “Go.” The squares vanish and the mouse pointer stays in the center of the screen.

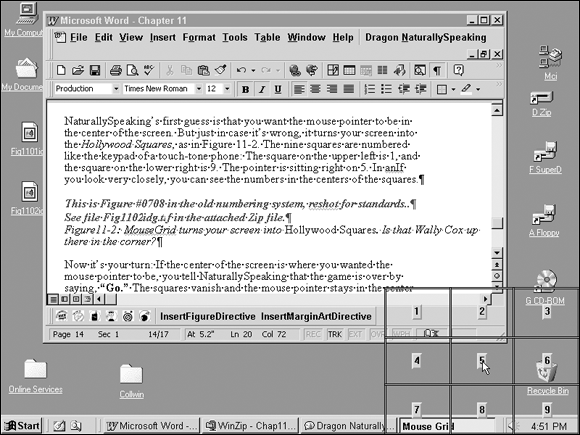

If the center was not the point you had in mind, say the number to tell Dragon Professional Individual the square your chosen point is in. For example, you may say, “Nine,” indicating that the point is in the lower-right part of the screen. Dragon Professional Individual responds by making all the squares go away other than the one you chose. Now Dragon Professional Individual guesses that you want the mouse pointer to be in the center of that square. But just in case it’s wrong, it breaks that square into nine smaller squares (see Figure 15-4). These squares are numbered 1 through 9, just like the larger squares were.

Again, either you say, “Go” to accept Dragon Professional Individual’s guess and end the game, or you say a number to tell it which of the smaller squares you want the mouse pointer to be in. It then breaks that square up into nine really tiny squares, and the game continues until the pointer is where you want it.

This description makes it sound as if you’ll be old and gray before the mouse arrives at the point you had in mind, but, in fact, this process happens very quickly after you get comfortable with it. If you are aiming for something like a button on a toolbar, two or three numbers usually suffice. You say, “MouseGrid 2, 6, 3, Go,” and the mouse pointer is where you want it.

You can use “Cancel” as a synonym for “Go.” (This situation may be the only one in human history where “cancel” and “go” are synonyms.) I choose between them according to my mood: If I succeed in putting the mouse pointer where I want it, I say, “Go.” If I just want out of the game, I say, “Cancel.” It makes no practical difference.

If you want to move the mouse pointer to a place within the active window, you can restrict MouseGrid to that window by saying, “MouseGrid Window” instead of “MouseGrid.” Now only the active window is broken up Hollywood Squares style. The process of zeroing in on the chosen location is the same (for example, “MouseGrid Window 2, 7, Go”).

You can also get out of MouseGrid by giving a click command (which is probably why you were moving the mouse pointer to begin with). So rather than saying, “MouseGrid 5, 9, Go” and then “Click,” say, “MouseGrid 5, 9, Click.” This trick works with any of the click commands, and also with “MouseGrid Window.” See “Clicking right and left,” later in this chapter.

You can also get out of MouseGrid by giving a click command (which is probably why you were moving the mouse pointer to begin with). So rather than saying, “MouseGrid 5, 9, Go” and then “Click,” say, “MouseGrid 5, 9, Click.” This trick works with any of the click commands, and also with “MouseGrid Window.” See “Clicking right and left,” later in this chapter.

Nudging the mouse pointer just a little

If the mouse pointer is almost where you want it and just needs to be nudged a smidgen, use the mouse pointer commands “Mouse Up,” “Mouse Down,” “Mouse Left,” and “Mouse Right.” You need to attach a number between one and ten to the command in order to tell the mouse how far to move. So, for example, say, “Mouse Up Four,” and the mouse pointer dutifully goes up four.

“Four what?” you ask. Four smidgens, or four somethings, anyway. Dragon Professional Individual Help calls them units. Ten minutes of experimentation has convinced me that a unit is about three pixels, if that helps. (Your computer screen is hundreds of pixels wide.)

All you really need to know about units is

All you really need to know about units is

- They’re small, so “Mouse Right Six” isn’t going to move the pointer very far. (For big motions, use “MouseGrid.”)

- They’re all the same size, so “Mouse Down Three” is going to move the pointer three times as far as “Mouse Down One.”

As with “MouseGrid,” you can combine the mouse-pointer commands with the click commands. Instead of saying, “Mouse Left Ten,” and then “Double Click,” you can say, “Mouse Left Ten Double Click.”

Running applications by name

Running applications by name Opening files and folders by name

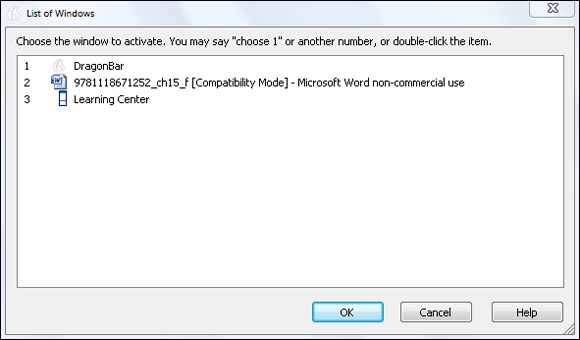

Opening files and folders by name Switching from one window to another

Switching from one window to another Talking to your mouse

Talking to your mouse Dealing with dialog boxes

Dealing with dialog boxes You may want to use these new commands to leverage Windows new search charm function. Do this by saying, “Charms Bar,” “Open Search Charm” and then dictate your search and say, “Press Enter.”

You may want to use these new commands to leverage Windows new search charm function. Do this by saying, “Charms Bar,” “Open Search Charm” and then dictate your search and say, “Press Enter.” Don’t shut down the computer by voice, unless you have challenges that prevent you from doing it any other way. In general, shutting down Windows with a lot of applications running (especially robust applications like Dragon Professional Individual) upsets the system. At the very least, it causes an application to do something illegal that makes Windows shut it down in an unnatural way. Some data could be lost in the process. Of course, some Windows operating systems run better than others, and you may get lucky. But why take the chance?

Don’t shut down the computer by voice, unless you have challenges that prevent you from doing it any other way. In general, shutting down Windows with a lot of applications running (especially robust applications like Dragon Professional Individual) upsets the system. At the very least, it causes an application to do something illegal that makes Windows shut it down in an unnatural way. Some data could be lost in the process. Of course, some Windows operating systems run better than others, and you may get lucky. But why take the chance?

The MouseGrid is not supported in Windows 8 Modern UI.

The MouseGrid is not supported in Windows 8 Modern UI.