Brand Management versus Brand Leadership

There are basically two different orientations toward brand: as images and as promises. It’s not surprising that there are two fundamentally different approaches to brand development as well. These two approaches, brand management and brand leadership, are codified by David Aaker and differ in a variety of ways.

Brand management focuses on the short-term. Its primary tool is promotion. Brand managers never have enough money and seldom have true control over the dollars they do have. Brand leadership is about the long-term. Brand leaders understand that building brand equity takes time, money, and talent. They know that a successful brand is not built in one budget year or one product launch. Brand leadership is based on the premise that brand building not only creates brand equity, but is also necessary for institutional success. With brand leadership, the institution’s most senior leaders recognize that building the brand results in a competitive advantage that pays financially.

Brand management is tactical, visual, and reactive. It’s preoccupied with the 3 Ls of branding: look, letterhead, and logo. Brand leadership is visionary and promise-driven. It concentrates on building brand value that translates into loyalty and market power. Metrics are in place to measure progress. The goal is brand equity.

Brand management and brand leadership represent two ends of a vast continuum. For many marketers, brand leadership might initially be out of reach and exists only on the company’s annual report. Their quickest gains might actually be generated by a consistent brand management strategy. To build a brand promise that consumers will value and, in doing so, help build brand equity, it is essential for everyone in that continuum to understand the progression of branding from management to leadership.

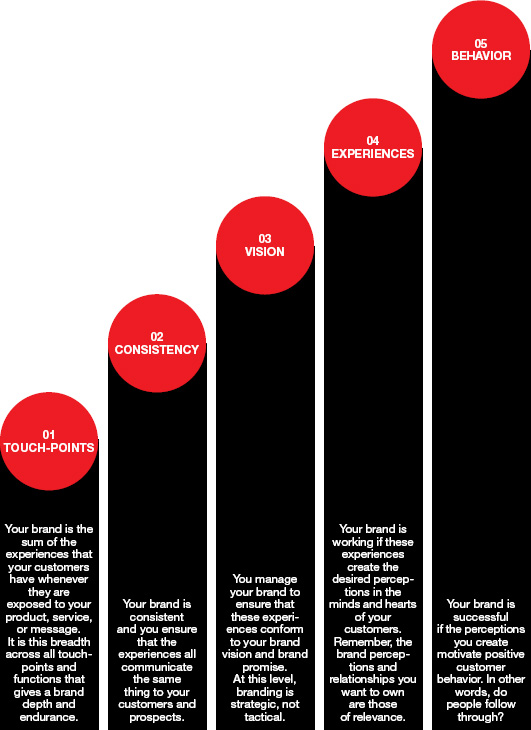

As you look at these five brand stages, note how they are tiered. You need to firmly establish one before you can move on to the next.

Understanding Brand Architecture

Creating a clear brand architecture to help structure position for today and tomorrow helps build that brand by ensuring everyone within an organization works to a common and clearly understood goal.

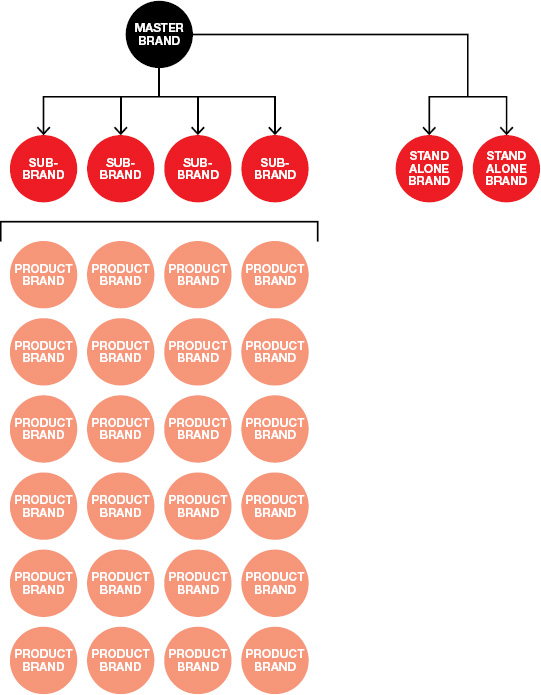

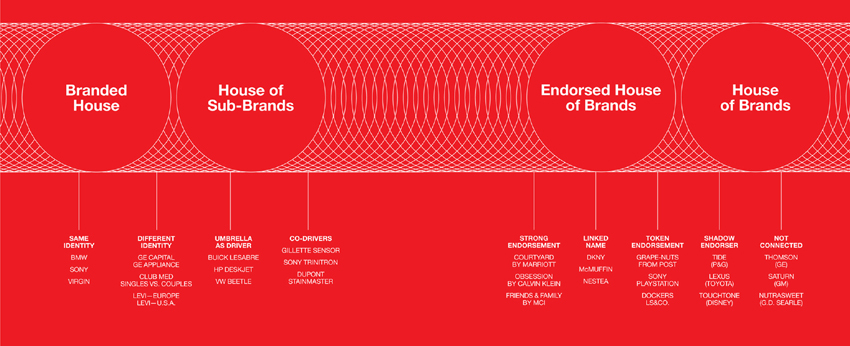

P&G and PepsiCo have hundreds, GM has 8 brand names, BMW has 3, IBM has 2, and Starbucks and Apple have 1. Between mergers and acquisitions, aggressive brand extensions, and the increasing complexities of sub-brands, endorsed brands, and co-brands, it gets more and more complicated. Often the task includes a periodic regrouping of multiple product groups and brand families, repositioning them to reflect their role in the market and to create a structure for immediate success. Establishing a clear and coherent brand architecture creates structure within which vital day-to-day tactical decisions can be made. Without this brand architecture in place, these tactical decisions become strategic and long-winded in nature.

Brand architecture is the logical, strategic, and relational structure for all of the brands in the organization’s brand portfolio. The objective is to maximize clarity, synergy, and leverage to maximize customer value and internal efficiencies.

Understanding Brand Architecture

Advantages of developing a brand architecture:

Understanding Architecture and Positioning

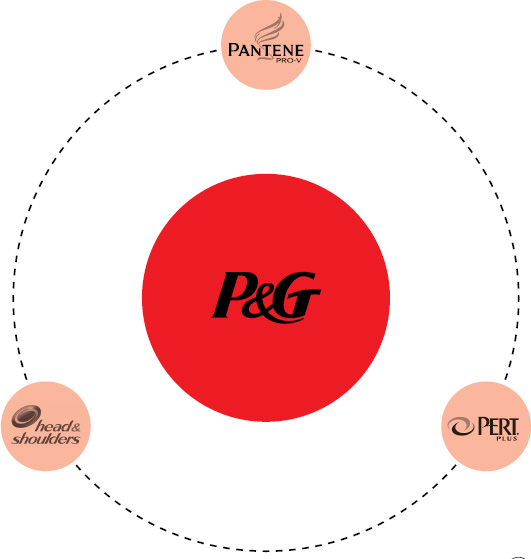

P&G’s brand architecture effectively manages the relationships between product, brands, and market segments. Head & Shoulders dominates the dandruff control shampoo category and Pert Plus targets the market for combined shampoo and conditioner. Pantene is positioned as a brand with a technological heritage and the power to enhance hair vitality. These three brands optimize their brand coverage by not being merchandised under a P&G product brand name. The lesson? Avoid a brand association that is incompatible with another offering and may adversely affect its performance.

Understanding Brand Architecture

It is very difficult to offer a generalization on how to put a vast number of brands in categories and wed sets of them and their relationships into a composite brand architecture. Each industry and category context is different, as are corporate views. The tendency is toward having a master brand. Only when there is a compelling need (and a budget) should a separate brand be considered. The big question is: can the business support a new brand?

The needs usually consist of one or more of the following:

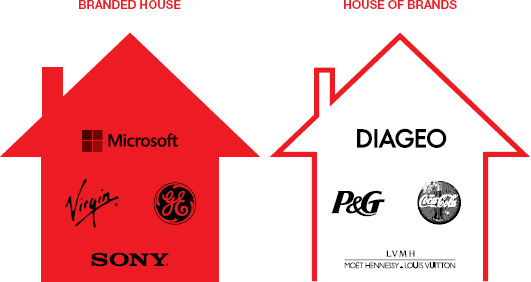

Brand Separation Spectrum

Case Study: Sony Brand Architecture

Sony chooses a single-minded, powerful, and yet flexible architecture and leverages their corporate brand in many different ways.