Pacific Northern Hemisphere

DECEMBER-FEBRUARY

>>> Every group has an aggressor. And among this family of swells, that aggressor is the one blasting out of the Pacific’s Northern Hemisphere. Siberian in origin and typically trained for battle in the Bering Sea, North Pacific swells consistently show us the ocean’s dark side.

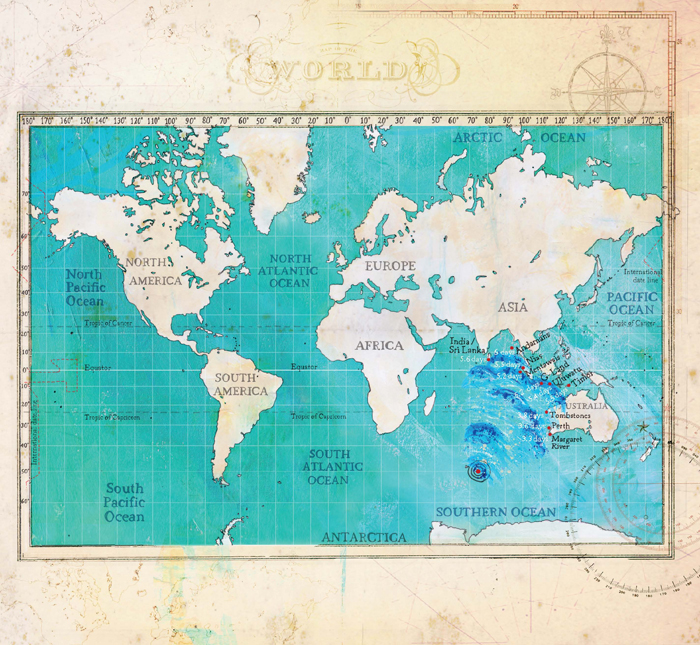

Depending on the year, anywhere from ten to twenty significant storms will gain momentum off Japan, charge over the dateline, and send energy toward numerous coastlines. Unlike other storm corridors, where massive low-pressure systems spin in isolation, the North Pacific presents a number of obstacles. On the front lines are the Aleutian Islands and Alaska, which stare these violent storms in the eye and regularly endure massive short-period swells. Take a look at the Dutch Harbor buoy in the Bering Sea during any big winter low-pressure, and you’ll understand why so many Alaskan king crab fishermen die each year on the job.

Next on the North Pacific’s hit list is Hawaii, home of some of the most famously large waves in the world. The pounding continues along the American West Coast, Mexico, the northern reefs of Tahiti and the Galapagos and—one week later—the north coast of Peru. Waves from these storms tend to be more volatile and unyielding than others, jumping from two to twenty feet in a matter of hours in some places and combining with seasonal high tides to add even more punch and property damage.

These waves can also kill. Not only do North Pacific swells create the “world’s most dangerous job” in the Aleutians, they are responsible for most of surfing’s highly publicized deaths. The majority of these have occurred at Pipeline, where large waves, big crowds, and a shallow reef bottom make for a lethal combination. They also occur at spots like Maverick’s in Half Moon Bay, where the force of a wave will hold a surfer down beyond the point of no return. Most recently, Hawaiian surfer Sion Milosky, a rising big-wave star, simply couldn’t resurface after a bad wipeout there. Waves can kill anywhere, but they tend to kill more often in waters stirred up in the North Pacific.

It is perhaps for this reason—along with their sheer height—that North Pacific swells tend to be the most remembered. Navy seamen likely use the winter of 1965, when a rogue wave in the North Pacific destroyed ninety feet of the USS Pittsburgh, as a cautionary tale. Beachfront homeowners in California surely remember the winter storms of 1982–83, when El Niño-fueled swells combined with 7.0 high tides gave new meaning to the term ocean view. And surfers can rattle off a number of years etched into the history books: the “Swell of ’69” that closed out the North Shore of Oahu and made big-wave surfer Greg Noll quit for good after attempting a thirty-footer at Makaha; the winter of ’82–83, when normally dormant coastlines like Santa Barbara turned into world-class surfing destinations; and January 1998, when Oahu’s Outer Reefs produced rideable waves of more than eighty feet.

Death, destruction, record-breaking heights…in a world of constant waves, the North Pacific regularly finds a way to stand up and get our attention. And it has our attention all winter long.

California Street, Ventura

Northern Baja, Mexico

>>> When high pressure builds over Nevada and Utah and the first wisps of warm, dry air start blowing toward the coastline, it is literally a red flag for any California community with chaparral. The Santa Anas (better known as Devil Winds) tend to bring out the worst in a few of our fellow humans, turning places like peaceful Malibu into a war zone with the flick of a match. It’s amazing how such a bad thing for land is such a good thing for the ocean. Santa Anas serve as one giant push broom for the West Coast beaches, sweeping out all the imperfections into hand-sculpted works of art. When they happen to coincide with a significant swell from the North Pacific, the results can be six-foot flawless peaks lit by a smoky orange sun.

>>> The best storm-producing conditions in the North Pacific are a phenomenon famously known as El Niño, which comes around every ten years or so as a result of warming equatorial waters in the Pacific. El Niño disrupts the typical global weather pattern and is blamed for everything from forest fires in Indonesia to flooding in Somalia. It also adds fuel to the North Pacific (warmer water enhances storms), creating a “steroid effect” on developing low-pressure systems. So, while some regions in the world dry up, Hawaii and the West Coast are flooded with both rain and swell. It’s no coincidence that all the biggest years on record for waves—1969, 1983, 1998, 2010—are El Niño years.

Maverick’s, Half Moon Bay, California

>>> There are many scary things about big-wave surfing. But perhaps what captures people’s imagination (and fears) the most is the prospect of being “caught inside.” It’s the avalanche dilemma: What do you do when a forty-foot wall of whitewater is about to mow you over? Run? Stay put? Let out a faint cry for help? In this case, it’s dive as deeply as you can in the few seconds you have. Unfortunately, these avalanches run deep, extending fingers of turbulence to depths up to twenty feet under a fifty- to sixty-foot wave. Make it below those fingers and it’s as tranquil as a swimming pool. Get caught, and you’ll be tossed around like a toddler in a tornado, released only when the wave decides to let you go. Even worse? Gasping to the surface and facing another one right behind it.

>>> A big swell at a wide-open beach like Morro Bay appears impenetrable, just an endless row of angry lines. Writer Jack London drew that same conclusion on the South Shore of Oahu and, a hundred years later, he still describes it best: “One after another they come, a mile long with smoking crests, the white battalions of the infinite army of the sea.”

>>> Why is Hawaii home to some of the biggest waves on the planet? Most of it has to do with positioning. On the same latitude as Southern California but floating out there in the mid-Pacific, the islands are typically about one thousand five hundred miles from the center of passing North Pacific storms—the perfect range for maximum firepower. There are other areas where storms and even swell size are just as big, but Hawaii’s reefs—with no continental shelf to get in the way—have been pounded, groomed, and refined for millions of years. Just like stadiums built to hold one hundred thousand people, Hawaii’s Outer Reefs are built to hold hundred-foot waves. And they do it with room to spare.