Atlantic Hurricane

SEPTEMBER-NOVEMBER

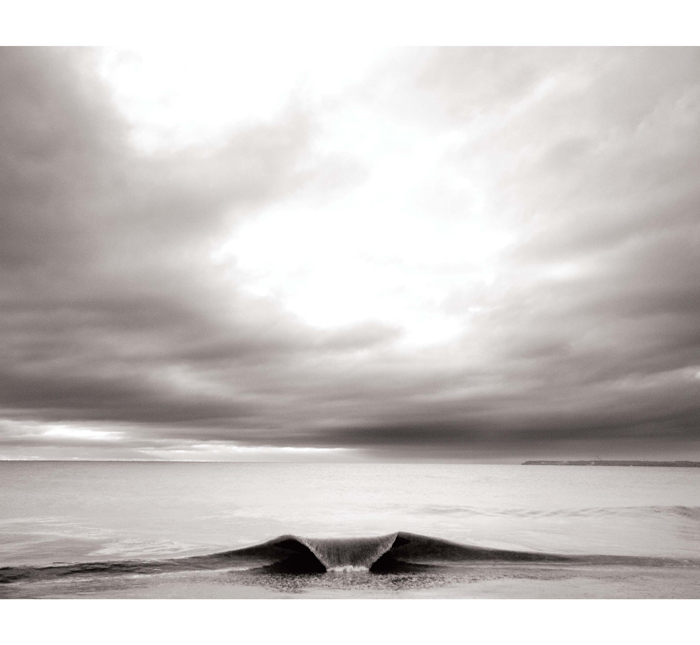

>>> Hurricanes and their resulting swells defy all reason. We can try to humanize them by giving them names like Emily and Frances. We can guess their next move with a supercomputer and trajectory models. We can even try to tame them by shooting “hurricane-busting” gel into the clouds. But none of these solutions do us much good. In the end, hurricanes can’t be trained. They act; we react.

While most large low-pressure systems burn slowly and steadily, hurricanes are more like forest fires. In the eastern Atlantic, thunderstorms typically move off the coast of West Africa near Cape Verde and converge with warm ocean vapors and surface winds. These three elements combine to create the out-of-control blaze we’re all familiar with.

Once this blaze begins, the only thing we can do is ride it out. Hurricanes (also known as cyclones in the southern hemisphere and typhoons in the western Pacific) have a minimum wind speed of 74 mph and move at an average of 15 to 30 mph. When a system crosses the Lesser Antilles threshold and makes a turn to the right, the normally wave-starved East Coast buzzes with activity and anticipation. Whipping, sideways rain; boarded windows and barricades; evacuation orders and emergency vehicles; and an ocean transformed from tranquil to treacherous in a matter of minutes—the coastline comes alive. Anywhere from the Caribbean to Canada could be slam-dancing with swell.

A hurricane wave is different from its long-distance cousins. Swells created thousands of miles away make for organized sets of three to four waves, fifteen to twenty seconds apart. But hurricane swells, often created only a few hundred miles away, make a more continuous train of waves, generally no more than eight to ten seconds apart. It’s not uncommon to see as many as fifteen waves in a single set during a hurricane swell—with little rest between them.

These swells are also more accurate. While large storms from the northern and southern hemispheres spray out broad bands of swell like a garden hose, hurricanes can deliver waves with laser-like precision—in some cases only a few miles wide. South Florida surfers will likely never forget the day Hurricane Isabel sent swell through the narrow Providence Channel in the Bahamas and delivered large, Hawaiian-style surf specifically to Delray Beach in 2003. As surfers at Delray raved, locals at nearby Pompano and Palm Beaches wouldn’t have had a clue. The conditions at their beaches—just a few miles to the north and south of Delray—were as small as a typical summer day.

Each new hurricane is another wildcard from the deck. One—like Felix in 1995—might be an incredible wave machine, stalling off the coast of North Carolina, slowly making its way northwest, and never reaching landfall. As Felix spun 200 miles off the coast with winds up to 140 mph, it generated huge swells all the way to Newfoundland and eventually to Iceland and beyond. One offshore Canadian buoy recorded swell heights at 82 feet. Damage: relatively minimal.

Another, like Andrew in 1992, is more of a wrecking ball. Like so many destructive hurricanes, Andrew missed that right turn in the Caribbean and made landfall in the Bahamas, Florida, and Louisiana as a Category 5. Sustained winds: 175 mph. Massive storm surge up to 23 feet. Dozens of deaths and $40 billion in damage.

Both examples show how fast a hurricane can turn on us. One minute, a hurricane’s transformative effect on the ocean has us running toward the beach. The next, it has us running toward the hills.

>>> If hurricanes (and cyclones and typhoons) generate the ocean’s highest wind speeds, why don’t they necessarily generate the world’s largest swells? Most of this has to do with physics. Wave-forecasting experts identify a point of diminishing returns in wind speeds and swell generation, with the sweet spot in the range of 50 to 60 mph. It’s at this speed where the ocean is whipped up, organized into major defined swell, and projected with purpose. Higher windspeeds tend to be overkill. At about 100 mph, the tops of open ocean waves even collapse over themselves, lessening the blow as they approach shore. The other factor limiting wave size is surface area. Unlike the vast ocean fields of the upper and under worlds, an Atlantic hurricane is more like a cannonball in a kiddie pool. There is not enough room for these incredibly powerful systems to grow, stretch, and make a maximum splash.

>>> We can thank Atlantic Hurricane Grace for helping inspire the term Perfect Storm. In late October 1991, the remnants of Grace merged with a powerful cold front bearing down from Canada. This created a massive “nor’easter” subtropical low that generated thirty-foot surf along the Eastern Seaboard, sunk the seventy-foot fishing boat Andrea Gail, and became immortalized in print and film. It’s during these types of storms when the mythical “rogue wave” has the highest chance of occurring. Rogue waves happen when several different swells—all at different speeds, heights, and directions—combine into one massive collapsing wall of water in the middle of the ocean. A hundred feet or more, gone as quickly as it springs up, the rogue wave is every captain’s bogeyman.