Robbins’s peg

Pitch 6 New Dawn; Pitch 1 Reticent Wall

I PULLED UP onto Lay Lady Ledge the following morning, just in time to watch the Russians disappearing up the wall with a wave.

The ledge was large, triangular and sloping, set within a deep corner, around 200 metres up the wall. A small barbecue was stashed amongst some boulders at its back. The New Dawn route, which I had followed up to the ledge, and which was first climbed by Charlie Porter in 1972, now carried on upwards, while the Reticent headed off on the right-hand side.

Charlie Porter was a Yosemite legend who tackled many of the hardest walls in the 70s, often solo, redefining hard aid climbing. This ledge must have been welcome to him after the steep pitches below, although it came at a high price. Porter had set down his haul bag containing his food and sleeping bag but he had neglected to clip it in, no doubt because of the size of the ledge. Unfortunately, the ledge has a slight angle to it, and Porter turned to see the bag rolling away. Giving chase, he thankfully stopped short of the edge as the bag went over and crashed down the wall below. Most climbers losing their sleeping bags and food would have retreated, but not Porter, who carried on and altogether took seven days to complete another first ascent.

Porter had long been a hero of mine, both for his toughness and for the quality and vision of his routes, climbed at the limit of the gear used at the time and at the limit of what was imagined to be possible. He took this ability to suffer from Yosemite to the Arctic, climbing a big new route on Baffin Island, then on to a mind-bending solo ascent of the two-kilometre-high Cassin route on Denali, the highest mountain in North America and considered one of the hardest mountain routes in the world. Always reticent about his achievements, Porter gave up climbing at the top of his game, swapping his haul bags and ropes first for a kayak, making the first solo circumnavigation of Cape Horn, then a yacht. The last I heard, he was still active down at the tip of South America, a well-known skipper sailing out in the harsh South Atlantic and the fjord-lands of Patagonia and Tierra Del Fuego.

What would I do if I gave up climbing after this?

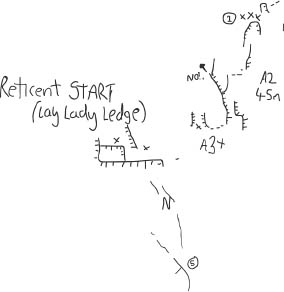

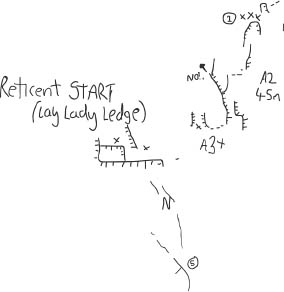

I hauled up my bags, and then, pulling out my hand-drawn topo, I tried to work out how to do the first pitch. The first pitch of the Reticent.

I’d been told that the Reticent was so hard that even the easiest pitches were harder than the hardest climbs I’d done. Looking up the blank sweep of granite I could understand why. It looked impossible. There simply didn’t seem to be anything there at all, no cracks or edges to use to ascend, let alone places to protect myself. Worse still, the pitch stepped off the ledge, so within a move you were suddenly faced with having a huge drop, six pitches of vertical rock, beneath your feet.

Impossible.

I looked harder.

There was no way.

I sat down on the ledge, feeling despondent. I’d been an idiot. What had I been thinking? All I could do was go down.

Down.

My mood lifted. I suddenly felt relieved. The doubt was over. I could only go down.

At least you know now that it’s too hard for you.

At least not many people know what you wanted to do.

I felt foolish, it should have been obvious that this would happen. I was so out of my league. I should have listened to my instinct lower down.

At least I could still retreat from this point.

I looked down at the valley, people setting up picnic blankets in the meadow, ready for some climber-watching.

I could be down in a few hours.

Maybe I could just go home.

A mouse scuttled across the ledge at my feet, and stopped for a second, perched on the lip of the ledge before darting up a crack and up the wall.

Even a mouse can scale a big wall.

I wondered how much bigger a big wall was to you if you were a mouse.

Maybe you can do it?

I thought about Royal Robbins and his ground-breaking first solo ascent of El Cap in 1968. He’d started the climb knowing that only a handful of teams had ever scaled El Cap, teams comprising the cream of North American climbing. Robbins had made many of these early ascents, but now he stood alone, with 3,000 feet of climbing above him – the route, the Muir Wall, hadn’t even had a second ascent. It was a giant step into the unknown, both in terms of climbing, and in self-belief, but perhaps Robbins knew there was no one else in the world who had the experience or skills to pull it off. In terms of world climbing this would be equivalent to landing on the moon.

Several days later Robbins was not sure if this was an attempt too far. His confidence and belief were leaving him bit by bit, metre by metre, peg by peg. The work involved, leading, cleaning, hauling, combined with the difficult climbing – not to mention the loneliness and self-doubt caused by having no one to share the experience – had convinced him that it was beyond him.

‘I dug into the rucksack of my soul and found it was just an empty husk.’

Robbins decided he would abseil off the following morning.

Yet when morning came he decided to place one more peg. Just one. In it went. Perfect. He clipped his aiders into it and stepped up. It didn’t seem right to place just a single peg, and so he placed another, then another, never thinking any further than the next.

Ten days after leaving the ground Robbins reached the summit, his hardest climb over, a turning point in his life.

All soloists think about Robbins and his ascent of the Muir, his antiquated gear, no portaledge, only pegs, no chance of a rescue. What he wanted was more than just a first, or to break a record, or to be famous. He wanted something deeper and more meaningful than that. The closer he came to failure, the closer he came to finding what all soloists are looking for: to break themselves apart on the wheel of a climb, to know what they have chosen to do is beyond them, to discover they are empty and wanting, yet somehow to find the strength to push on regardless. To dare and try their best. To overcome every instinct and rational thought. To push on. To travel alone to the height of themselves. To believe such a thing is possible.

I thought about Robbins’s peg.

I stood up and ran my fingers up the wall, looking for something, anything, a reason to carry on, an excuse to go down. The Russians had passed this way: there must be something.

With the tip of one finger I found an edge no bigger than half a fingernail. I had my first move.

I sat back down and looked up the wall.

Just do one move, that’s all.

I racked up all my skyhooks, hanging them from my harness like the tools of a torturer, spiked curved hardened steel, clipping a small one to my aiders, its point no bigger than the tip of a Biro.

I went back to the hold, and placed the skyhook. I gently tested it, half expecting it to spring out and bash me in the face. It flexed. It held. I slowly stepped up.

I clipped my harness into the hook, which was now at waist level, and sat there a few minutes, trying not to think about the drop below, even though a fall now would only be short.

I moved up the aider until the hook was above my knee and, balancing, felt for a second hook and my next move. My fingers touched an edge only the thickness of a matchstick.

I placed the second hook, smaller than the first, and, clipping in my other aider, slowly stepped up after again gently testing it. The ledge was only six feet below, but my heart was beating. It was high enough to bust an ankle, with the drop below the ledge adding to the feeling of exposure.

I tried not to think about the fact that I was actually climbing the Reticent Wall. Somewhere above were two bolts, but between us lay 200 feet of the most difficult climbing, and beyond them two thousand more feet. As in a game of chess I couldn’t allow myself to focus on winning, or even on a few moves ahead, but only on the next move and no further.

I stepped up and felt for the next placement.