Black bites

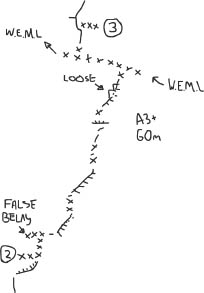

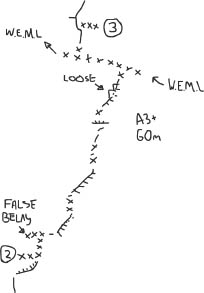

Pitch 3 Reticent Wall

THE STORM RAGED all night.

I was alive.

I knew I could just as easily have been dead, hanging frozen on the end of my haul line.

I lay in my warm sleeping bag on my portaledge, the flysheet clamped down tight around it, listening to the hail rattling on its taut skin, knowing I’d been lucky.

In the morning I emerged like a mariner from his crow’s nest. My home, now suspended from two bolts, was a shipwreck of storm-battered rigging, ropes, bags, hardware hanging from every portion of my camp, clipped on in haste last night. I found a food bag of bagels and cheese, climbed back into bed, and waited for the sun to take the post-storm chill out of the air.

From now on every night would be spent in this bed. My harness would stay on until I reached the top – slept in, climbed in, even worn on the toilet.

I ate a bagel and thought about how close I’d come to hypothermia the previous day. The reality was that I could have died.

I also thought about my past close calls – avalanches, falls, crevasses and falling rocks – and how each time, because the outcome was positive, the experience was simply shrugged off.

Perhaps what worried me was the fact that yesterday the outcome was black or white: either get back to the belay and live, or be stuck and die, first by losing all motor skills, then by swift hypothermia as my core temperature dropped until I lost consciousness. The significance of yesterday was not that it was any worse than other close calls, it was that it was experienced alone. I had been a victim of my own incompetence, but also my own saviour.

I had to start taking this more seriously, and that was best achieved by not wasting my mental energy or thoughts on useless doubts and fears. I had to keep a cool head and stay rational. I had perhaps two weeks of climbing left, and countless opportunities to make a mistake that could cost me my life. Next time I would probably not get a second chance.

The sun was getting close, so I sat up in my sleeping bag and started to warm-up my aching muscles. The tightness and stiffness in my back and biceps felt good, but it had been a long time since I’d felt so wasted. How would I feel a week down the line? Could my body and mind take it?

My fingertips were already looking pretty ragged, my fingernails scratched and sore around the edges. I wore fingerless leather gloves to protect my hands, but whatever you did your fingers always got hammered. I also had a few mosquito bites from my time in Camp 4, that had turned alarmingly black. I thought for a minute about blood poisoning, lying on my ledge slowly dying of septicaemia, waiting for a rescue that could take too long. I shook the vision from my head, knowing that fear of dying was almost worse than dying itself. If I got blood poisoning then I got blood poisoning. I’d worry about it if it happened.

I swung my legs over the edge of the ledge; the drop below was now over a thousand feet. I could see people moving around, carrying haul bags slowly up the trail to start other routes, oblivious to my presence.

I looked up and tried to spot the next belay. All I saw was seemingly blank rock, but I knew that somewhere up there I’d find bolts.

Bolts are 12-millimetre steel rods with a plate screwed into the end for a karabiner, and they provide islands of security in what can otherwise be a desert of fear and anxiety.

On any climb you have to trust that you, your partner, maybe even three or four of you, plus all your monstrous haul bags weighing hundreds of kilos, can hang solely from two steel rods no thicker or longer than your little finger. Such bolts gave the only security on a climb like this. They provided the comfort of knowing that although you could potentially fall and rip every piece of gear out, taking maybe a 400-foot whipper, at least the belay would hold.

The numbers of bolts drilled on a first ascent is often used as an indicator of how brave the first ascensionists were. Most climbers, running it out on terrible gear, and looking at a death fall, will eventually reach for the drill and place a bolt for protection mid-pitch, or place two bolts in order to make a belay and a shorter pitch. The Reticent has very few drilled holes, the belays are far apart, the team had pushed their skills and mental fortitude to the max. The result was pitches that went on seemingly forever, often longer than the length of a standard rope. The mental weight of the climbing built with every metre until the leader would be a gibbering wreck, praying to get to the bolts before his mind snapped.

The sun was only fifty feet away now, so I pulled on my shoes, being careful not to drop them. Next came my knee pads, then my helmet and leather gloves, the material stiff with cold until I flexed it back into life. I pulled myself up and stood on the unsteady portaledge, the thin fabric holding me above the void. I strapped on my chest harness, used to hold all my gear, and began clipping on nuts, pegs, cams, hooks, copperheads, each one making me feel heavier and heavier. Next came the ropes, tied to the belay I’d escaped from last night in the storm, stacking them ready for the next pitch. Lastly I set about dismantling my portaledge and stuffing my sleeping gear away in my haul bags, each piece fitting into its own stuff bag, each stuff bag stowed in its set place in the haul bag. Finally I was ready to move.

The sun was now two hundred feet further down the wall. It was already getting hot. I clipped in my jumars and started up, back to the next belay where I’d haul up my bags and begin the next pitch.

I still couldn’t see the belay bolts.

My brain throbbed, my head felt as if it was on the boil. I took the last sip of water from the bladder attached to my back. It was hot. Grainy granite dust and sweat covered my face, stinging my eyes and finding its way into my cut fingers each time I tried to wipe it away. I could taste the wall and my fear.

I’d been climbing for four hours; the wall was the blankest section of rock I’d ever climbed, smooth and almost faultless. The only way to progress was to follow a braille of tiny geological flaws: a scab of iron, a crystal standing proud, a fingernail edge, revealing themselves one at a time, more often than not at the very limit of my reach. This route must have been climbed by fucking giants!

I hung from a single hook, a few millimetres of hardened steel clawed over a tiny crystal that stood proud of the wall. The last piece of protection was several metres below; my rope snaked in the wind down to its winking karabiner. If I messed up here I’d be in for the biggest fall of my life. I’d be falling into space. I wouldn’t hit a thing. The thought brought little comfort.

The hook was called a pointed Leeper, designed by a climber called Ed Leeper back in the sixties and still one of the best hooks around. I looked at it, and thought it amazing that all my weight could be held by such a small piece of folded steel. I knew Leeper had been a rocket scientist once, with climbing hardware as a sideline. This hook had been made by hand in his forge in Colorado. It was a work of minimalist art. On the scariest placements I would often repeat the words ‘Leeper was a rocket scientist, Leeper was a rocket scientist’, a mantra that for some reason seemed to help.

I’d hung from the hook for fifteen minutes, trying to find the next tiny hold, repeatedly stepping up high in my aiders, each time fearful I’d pull the Leeper hook off. The blanker the rock, the higher I had to step; the higher I stepped the more unbalanced and insecure I felt; the higher I went the bigger the chance I’d fall. I felt on the edge of control, tasting, hearing, feeling the drop below. Being so close to disaster was like falling itself, that stomach-lurching drop on a roller-coaster. I could feel the taunting pull of gravity.

I tried again, moving up the steps of the aider, one at a time, until the hook was at my knees. My sweaty hand fingered around for anything. My stomach muscles tensed as I held on to the hook with my other hand, every ounce of physical control used to avoid a slip.

There must be something.

My fingertip brushed an edge no bigger than the thickness of a tooth.

Too small. There must be something else.

Trying to stay calm and breathe evenly I felt around further, my body stretching out, looking for anything, a matchstick edge or matchstick flake.

Nothing.

I pulled up my other aider and clipped on a pointed Black Diamond hook, its tip filed sharp for the tiniest of edges. I clipped in a daisy chain and aider, stretched up and carefully placed it on the minuscule edge, trying to set it in the optimum position, difficult when I could only work blind by touch. The hook was placed and, careful not to disturb it, I crept back down on the aiders below and psyched myself up for the test.

You must calm down, be methodical, test the hook.

On hard aid, where falling has to be avoided, the only way to proceed with any degree of safety is to test everything. This is a rule I live by. No matter how poor, no matter how fragile, everything must be tested. By testing everything with your body weight, giving it a little bounce, then a few harder shocks, you know that the piece can hold you – it’s a psychological aid more than a physical one.

I eased my weight onto the Black Diamond hook in increments. Small jolts, slowly. My left hand held onto the Leeper hook below, my foot lifted off the aider by only a centimetre, ready in case the hook above popped.

I watched it flex, wobble, but hold. It defied all reason to hang on the edge. I rested back on the Leeper.

It must be the one.

I didn’t want it to be the one. I thought about the other climbers who had passed this way, tried to imagine what they had felt and thought.

Were they as scared as me?

I looked down at the rope, flapping in updraught, the fear of the fall rising in my throat like sick.

It must be the one. You must test it one more time, then get on it.

I began testing again, counting out the number of jolts.

One.

Two.

Three.

My body shock loaded the hook with increasing force.

Four.

Five.

Six.

Seven.

I pulled hard. I wanted it to fail. I wanted an excuse not to trust it.

Eight.

Nine.

Ten.

The hook held.

Eleven …

PIIIIIIINNNNNNNGGGGGGG!

The hook sprang from the edge and smashed into my helmet, sending me back into the Leeper hook below. Instinctively I caught myself with my hand, slowing my impact onto the hook, my foot falling back onto the aider, with a jerk.

I was off!

I let out an involuntary yelp, but my mind was screaming.

The whooshing fall didn’t come. I was hanging from the Leeper hook.

Calm down, you haven’t fallen.

I clipped back into the hook and tried to pull myself together.

I thought about a friend who’d made lots of hard and scary rock climbs, and whose advice on how to overcome fear had been, ‘Just imagine you’re someone else.’ This was the perfect time to find out if it helped. It didn’t.

I pulled myself up and searched once more for a better edge or flake, stretching up as far as I dared. All I could find was the same tiny edge. My head hurt. I wanted it to be over.

Keep focused. Don’t get sloppy. If you fall you’ll only have to climb all the way back up and do all this again.

I blindly placed the Black Diamond hook once more, and began a second bout of testing. It held. I tested it again, counting the jolts out. Ten. Twenty. Thirty. Again and again, until I had no excuse.

There was no way back, I had to commit to the hook.

Go on.

Holding my breath I transferred across. It felt as if my heart was shaking.

Go on. Go on. Go on.

I accidentally caught the Leeper hook with my foot and saw it tumble off its perch.

I was now totally committed.

No going back.

I hung, unable to move, waiting tense, for the whooshing fall, feeling that any movement would disturb the fine balance of hook and steel. My whole weight and future were focused on one square millimetre. I couldn’t imagine how it could be so strong, or the structure of granite be so resistant to my enormous and concentrated weight.

I hung there for ten minutes without moving, every second giving me hope.

You can’t get any heavier than this.

With bomb-defusing slowness I began to move up the aider, feeling the nylon stretch and shift, my eye never leaving the hook’s point, the fulcrum of all my hopes and fears.