CHAPTER 2

Founding New France

In the fall of 1604—sixteen years before the Mayflower’s voyage—a group of Frenchmen were about to become the first Europeans to confront a New England winter.

By the standards of the day, theirs was an elaborate undertaking. Seventy-nine men had crossed the Atlantic in two ships filled with the prefabricated parts needed to assemble a chapel, forge, mill, barracks, and two coastal survey vessels. They carefully reconnoitered the coasts of what would one day become Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and eastern Maine, looking for an ideal location for France’s first American outpost. They chose to build their fortified settlement on a small island on what is now the easternmost fringe of Maine, in the middle of a river they named the St. Croix. The site appeared to perfectly suit their needs: the island was easy to defend from European rivals, and the mainland shore had ample wood, water, and farmable plots. Most important, there were plenty of Indians in the area, as the river was a major highway for their commerce. Good relations with the Indians, their leaders had decided, would be key to the French project in North America.

1The expedition was led by an unlikely pair. Pierre Dugua, the sieur de Mons, was a French noble who had been raised in a walled château and had served as a personal advisor to King Henri IV. His thirty-four-year-old deputy, Samuel de Champlain, was supposedly the common-born son of a small-town merchant but was somehow able to gain personal and immediate access to the king anytime he wished and, inexplicably, had been receiving a royal pension and special favors from him. (Many scholars now believe he was one of Henri IV’s many illegitimate sons.) In France, Champlain and de Mons had been neighbors, raised a few miles apart in Saintonge, a coastal province in western France distinguished by its unusually mixed population and tolerance of cultural diversity. Both men had served on the battlefields of France’s religious wars, experienced firsthand the atrocities that can result from bigotry, and wished to avoid seeing them again. Their mutual visions of a tolerant, utopian society in the wilds of North America would profoundly shape not only the culture, politics, and legal norms of New France but also those of twenty-first-century Canada as well.

2The sieur de Mons envisioned a feudal society like that of rural France, only perfected. It would be based on the same medieval hierarchy with counts, viscounts, and barons ruling over commoners and their servants. Democracy and equality did not enter into the picture. There would be no representative assemblies, no town governments, no freedom of speech or the press; ordinary people would do as they were told by their superiors and their king—as they always had, as they had always been meant to. But there were differences from France as well. While Catholicism would be its official religion, New France would be open to French Protestants, who could freely practice their faith. Commoners would be allowed to hunt and fish—rights unheard of in France, where game belonged exclusively to the nobility. They would be able to lease farmland and, potentially, rise to a higher station in life. It would be a conservative and decidedly monarchical society, but one more tolerant and with greater opportunities for advancement than France itself. It was a plan that would meet unexpected resistance from rank-and-file colonists.

Champlain’s vision for New France was more radical and enduring than de Mons’s. While he shared de Mons’s commitment to creating a monarchical, feudal society in North America, he believed it should coexist in a friendly, respectful alliance with the Native American nations in whose territories it would be embedded. Instead of conquering and enslaving the Indians (as the Spanish had), or driving them away (as the English would), the New French would embrace them. They would intentionally settle near the Indians, learn their customs, and establish alliances and trade based on honesty, fair dealing, and mutual respect. Champlain hoped to bring Christianity and other aspects of French civilization to the Native populations, but he wished to accomplish this by persuasion and example. He regarded the Indians as every bit as intelligent and human as his own countrymen, and thought cross-cultural marriage between the two peoples was not only tolerable but desirable. It was an extraordinary idea, and one that would succeed beyond anyone’s expectations. Historian David Hackett Fischer has fittingly dubbed it “Champlain’s Dream.”

3The two Frenchmen’s ideal society got off to a poor start, largely because they had underestimated the severity of the New England winter. The first snows came to St. Croix Island in early October. When the river froze in December, the powerful tides from the Bay of Fundy smashed and shattered the ice, turning the waterway into an impassable field of jagged ice floes. Trapped on their tiny island, the settlers quickly ran short of firewood, meat, fish, and drinking water. The depth of the cold was something none of them was prepared for. “During this winter all our liquors froze, except the Spanish wine,” Champlain recalled. “Cider was dispensed by the pound . . . [and] we were obliged to use very bad water and drink melted snow.” Subsisting entirely on salted meats, the settlers soon began dying from scurvy, their tissues decomposing for lack of vitamin C. They all might have perished had the colonists not already established a friendly rapport with the Passamaquoddy tribe, who delivered an emergency supply of fresh meat during a break in the ice. Even so, nearly half the colonists died that winter, filling the colony’s cemetery with diseaseravaged bodies. (In the nineteenth century, when the cemetery area began to erode into the river, locals would begin referring to the site as Bone Island.)

4The French learned from their tragic mistake. In the spring de Mons moved the colony to a spacious harbor on the opposite side of the Bay of Fundy in what is now Annapolis Royal, Nova Scotia. Their new settlement, Port Royal, would become the model for the future settlements in New France. It resembled a village in northwestern France, from where almost all the settlers had come. Peasants cleared large fields and planted wheat and fruit orchards. Skilled laborers constructed a water-powered grain mill and a comfortable lodge for the gentlemen, who staged plays, wrote poetry, and journeyed into the fields only for picnics. Although their community was tiny—fewer than 100 men all told, once reinforcements had arrived from France—the gentlemen took little notice of their underlings; in their voluminous written accounts of their experiences, they almost never mention any of them by name. In winter they formed a dining club called the Order of Good Cheer and competed with one another to produce the finest gastronomy from local game and seafood.

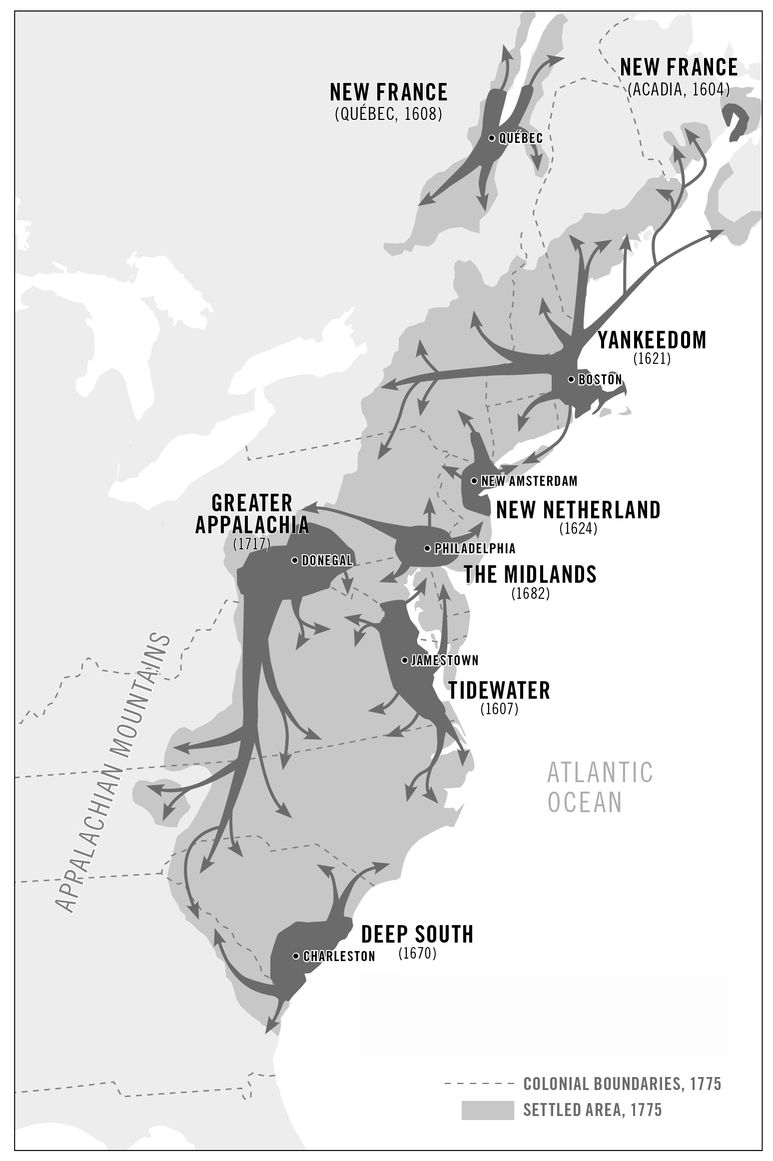

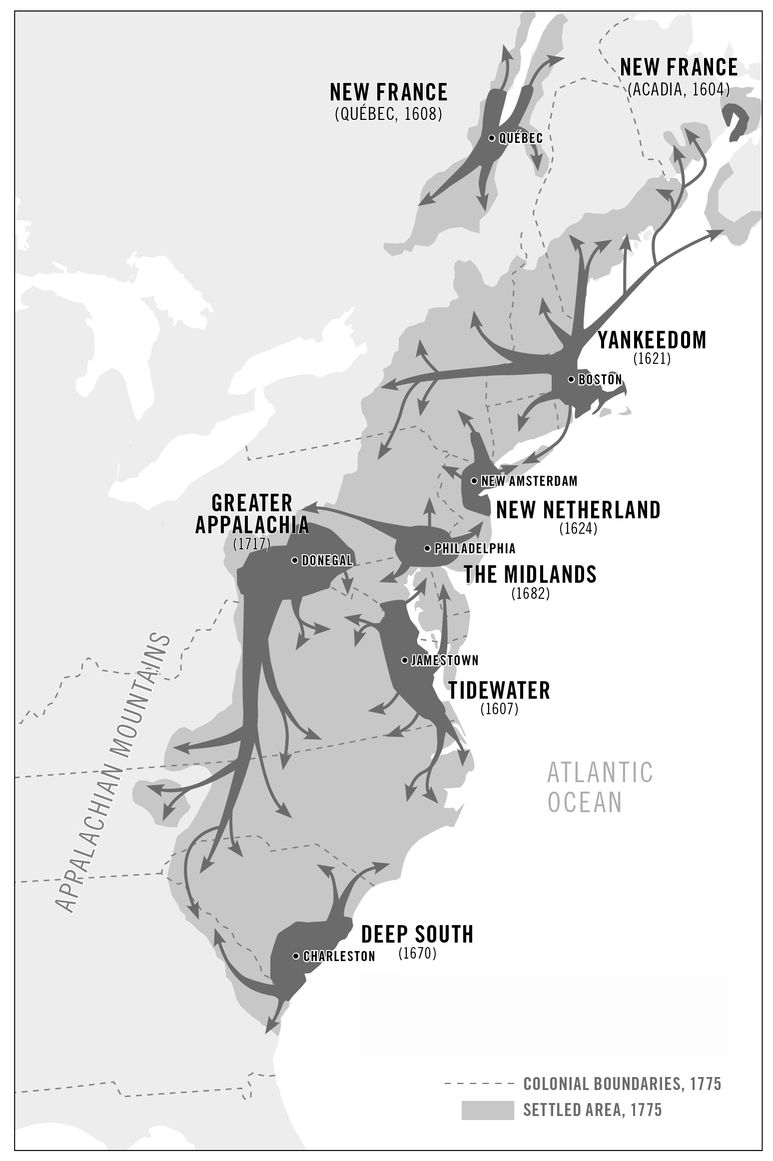

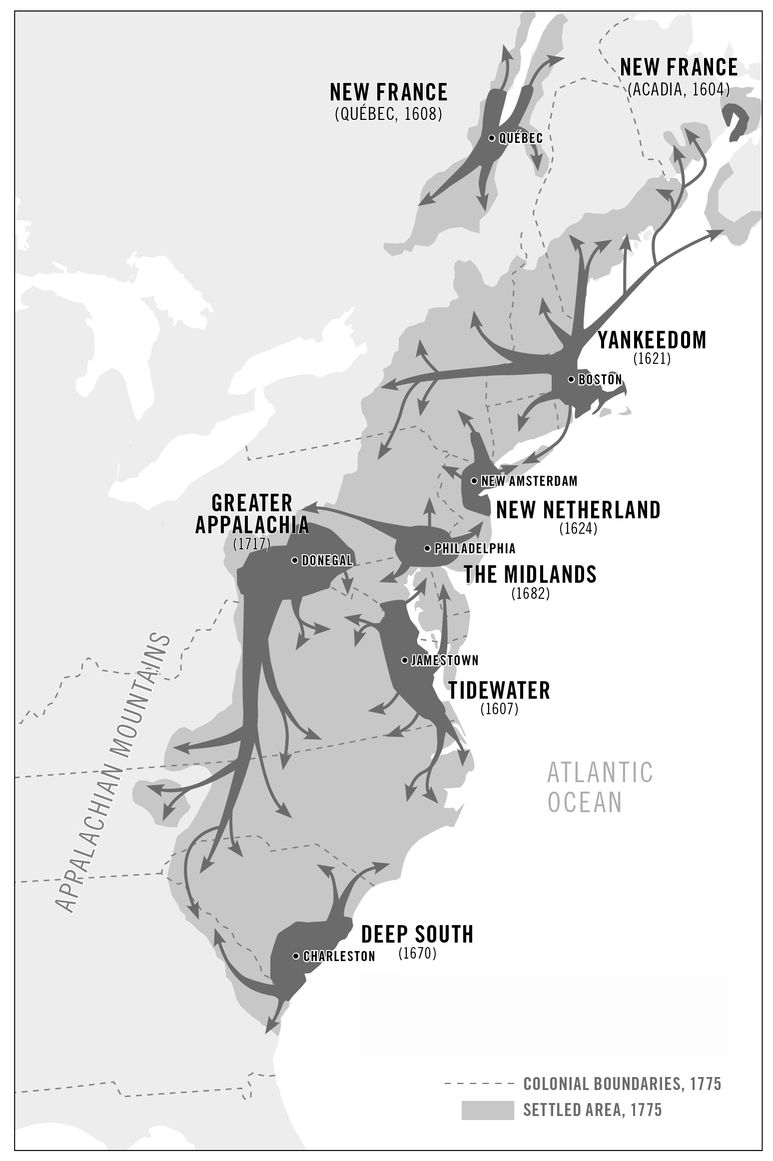

THE EASTERN NATIONS 1604–1775

While early settlers in Jamestown refused to sample unfamiliar foods and resorted to eating neighbors who’d starved to death, the gentlemen at Port Royal were feasting on “ducks, bustards, grey and white geese, partridges, larks . . . moose, caribou, beaver, otter, bear, rabbits, wildcats (or leopards), raccoons and other animals such as the savages caught.” Commoners weren’t invited to these feasts, and made do with wine and “the ordinary rations brought from France.”

5By contrast, the gentlemen treated the Indians as equals, inviting them to their feasts and plays. “They sat at table, eating and drinking like ourselves,” Champlain wrote of their chiefs. “And we were glad to see them while, on the contrary, their absence saddened us, as happened three or four times when they all went away to the places wherein they knew that there was hunting.” The French, in turn, were invited to Mi’kmaq festivals, which featured speeches, smoking, and dance, social customs Champlain and his colleagues were quick to adopt. At first they were helped by the presence of the interpreter de Mons had seen fit to bring to the New World, an educated African servant or slave named Mathieu deCosta, who’d been to Mi’kmaq territory before and knew their language. But the French gentlemen also studied the Mi’kmaq language on their own and sent three teenagers from their own families to live with the Indians so they could learn their customs, technology, and speech. The young gentlemen learned to make birch-bark canoes, track moose on snowshoes, and move silently through the forests. All would become leading figures in New France’s future province of Acadia, which theoretically spanned most of what are now the Canadian Maritimes. Two would serve as its governor.

6This pattern of cultural openness was repeated in Québec (which Champlain founded in 1608) and would be practiced across New France so long as it remained part of the French kingdom. Champlain visited various tribes in their local villages, sat in their councils, and even risked his life joining them in battle against the powerful Iroquois. He sent several young men to live with the Huron, Nipissing, Montagnais, and Algonquin to learn their customs. Similarly, as soon as new Jesuit missionaries arrived in New France, their superiors sent them to live among the natives and learn their languages so as to better persuade them to become Christians. The Montagnais reciprocated in 1628, entrusting three teenage girls to live in the future Québec City so that they could be “instructed and treated like those of [the French] nation” and perhaps married into it as well. Champlain championed the notion of racial intermarriage, telling the Montagnais chiefs: “Our young men will marry your daughters, and henceforth we shall be one people.” Following his example, French settlers in Québec tolerated unusual Indian habits, such as entering homes and buildings “without saying a word, or without any greeting.”

7 Other Frenchmen went further, moving into the forest to live with the Indians, a move encouraged by the critical shortage of women in Québec for much of the seventeenth century. All adopted Indian technologies—canoes, snowshoes, corn production—which were more suited to life in New France than heavy boats, horses, and wheat.

In Acadia sixty French peasant families lived happily at the head of the Bay of Fundy for generations, intermarrying with local Mi’kmaqs to such a degree that a Jesuit missionary would predict the two groups would become “so mixed . . . that it will be impossible to tell them apart.” Like other Indian tribes with whom the Jesuits worked, the Mi’kmaqs adopted Christianity but continued to practice their own religion, not believing the two to be mutually exclusive. Jesuit priests were seen as having one form of medicine, traditional shamans another. This hybrid belief system was not that dissimilar to the earthy Catholicism practiced by the Acadian peasants, infused with pre-Christian traditions that survive to this day among their Cajun descendants in Louisiana. In Acadia, where official authority and oversight was weak, French and Mi’kmaq cultures blended into one another.

While the French had hoped to peaceably assimilate the Indians into their culture, religion, and feudal way of life, ultimately they themselves became acculturated into the lifestyle, technology, and values of the Mi’kmaqs, Passamaquoddies, and Montagnais. Indeed, New France became as much an aboriginal society as a French one and would eventually help pass this quality on to Canada itself.

The Indians’ influence would also be the undoing of the French effort to transplant feudalism to North America. Starting in 1663, Louis XIV’s minions tried to bend New France’s increasingly aboriginal society to his will. The Sun King wanted a society in which most of the land was divided among nobles with ordinary people bound to it, toiling in the fields and obeying their superiors’ commands. A government bureaucracy would attempt to control every aspect of their lives, including how they addressed one another, what clothing and weapons a given class of people could wear, whom they could marry, what they could read, and which types of economic activities they could undertake. There were rules forbidding bachelors from hunting, fishing, or even entering the forests (to prevent them from “going native”) and penalizing fathers whose daughters remained unmarried at age sixteen or sons at twenty (to spur the colony’s growth). In the St. Lawrence Valley almost all arable land not reserved for the Church was divided among well-born gentlemen to enable them to become landed aristocrats, or

seigniors. Protestants were no longer welcome because, as Bishop François Xavier de Laval put it, “to multiply the number of Protestants in Canada would be to give occasion for the outbreak of revolutions.”

8Louis XIV also sent thousands of settlers to New France at the crown’s expense, including 774

filles de roi, impoverished young women who agreed to wed colonists in Quebec in exchange for a small dowry.

9 Officials at Versailles hired recruiters to round up indentured servants, who would be sold at bargain rates into three years of bondage to aspiring seigniors. Most of those sent to Canada in the seventeenth century came from Normandy (20 percent), the adjacent Channel provinces (6 percent), or the environs of Paris (13 percent), although a full 30 percent came from Saintonge and three adjacent provinces on the central Bay of Biscay. The legacy of these regional origins can still be seen in the Norman-style fieldstone houses around Québec City and heard in the Québécois dialect, which preserves archaic features from the early modern speech of northwestern France. (In Acadia, where the Biscay coast provided the majority of settlers, people have a different dialect that reflects this heritage.) Very few settlers came from eastern or southern France, which were remote from the ports that served North America. During the peak of immigration in the 1660s, most colonists came alone, two-thirds were male, and most were either very young or very old and had little experience with agriculture. The situation became so serious that in 1667 Jean Talon, Québec’s senior economic official, begged Versailles not to send children, those over forty, or any “idiot, cripples, chronically ill person or wayward sons under arrest” because “they are a burden to the land.”

10Regardless of their origins, most colonists found working the seigniors’ land to be burdensome. Few accepted their assigned role as docile peasants once their indentures were concluded. Two-thirds of male servants returned to France, despite official discouragement, because of rough conditions, conflict with the Iroquois, and the shortage of French brides. Those who stayed in New France often fled the fields to take up lives in the wilderness, where they traded for furs with the Indians or simply “went native.” Many negotiated marriages with the daughters of Native leaders to cement alliances. As John Ralston Saul, one of Canada’s most prominent public intellectuals, has characterized it, these Frenchmen were “marrying up.” By the end of the seventeenth century, roughly one-third of indentured servants had taken to the forests and increasing numbers of well-bred men were following them. “They . . . spend their lives in the woods, where there are no priests to restrain them, nor fathers, nor governors to control them,” Governor Jacques-René de Brisay de Denonville explained to his superior in 1685. “I do not know, Monseigneur, how to describe to you the attraction that all the young men feel for the life of the savage, which is to do nothing, to be utterly free of constraint, to follow all the customs of the savages, and to place oneself beyond the possibility of correction.”

11In contemporary terms, these woodsmen—or

coureurs de bois—were first-generation immigrants to aboriginal societies whose cultures and values they partially assimilated. Their numerous children were as much Mi’kmaq, Montagnais, or Huron as they were French; indeed, they formed a new ethnoracial group, the

métis, who, unlike New Spain’s mestizos, tended to be just as comfortable living in an aboriginal setting as in the European settlements. The coureurs de bois were proud of their independence and of the relative freedom of their seminomadic, hunter-gatherer lifestyle. “We were Caesars, [there] being nobody to contradict us,” explained one of the most famous, Pierre-Esprit Radisson, in 1664. Among these new Caesars was Jean Vincent d’Abbadie de Saint-Castin, a French baron who had served at Fort Pentagoet (now Castine, Maine), the Acadian administrative capital. Dutch pirates destroyed the fort in 1674, but Saint-Castin didn’t bother to rebuild it when he returned to the site three years later. Instead he set up a trading post in the middle of a Penobscot Indian village, married the daughter of Penobscot chief Madockawando, and raised a métis family in the Penobscot manner. His sons, Joseph and Bernard, would both lead Penobscots in raids against the English in the bloody imperial wars for control of the continent, becoming among the most feared men in New England.

12With much of their labor force deserting to Indian ways, the seigniors found themselves sinking into poverty. At least one was forced to work his own grain mill after his miller was drafted. Another donated his land to a nunnery, having become too old to work his own fields. Even leading families like the Saint-Ours and Verchères were forced to beg Louis XIV for pensions, salary-paying appointments, and fur trading licenses. “It is necessary to help them by giving them a means of . . . livelihood,” Governor Denonville wrote the crown, “for, in truth, without it there is a great fear that the children of our nobility . . . will become bandits because of having nothing by which to live.”

13At the same time, commoners displayed an unusual degree of independence and contempt for hierarchy. On the island of Montréal, settlers hunted and fished on the seigniors’ reserves, damaged their fences, and threatened their overseers. The obstinacy of the Acadian farmers infuriated an eighteenth-century colonial official. “I really think the Acadians are mad. Do they imagine we wish to make

seigniors of them?” he asked. “They seem offended by the fact that we wish to treat them like our peasants.” Throughout New France, rough equality and self-reliance prevailed over Old World feudal patterns. The French had intended to assimilate the Indians, but inadvertently created a métis society, as much Native American in its core values and cultural priorities as it was French.

14By the middle of the eighteenth century, New France had also become almost entirely dependent on Native Americans to protect their shared society from invaders. Even a century and a half after the foundation of Port Royal, there were only 62,000 French people living in Québec and Acadia, and only a few thousand in the vast Louisiana Territory, which encompassed much of the continental interior. To the south, however, France’s longtime enemies were gaining strength at an astonishing rate, for in the Chesapeake Tidewater and New England, two aggressive, vibrant, and avowedly Protestant societies had taken root, cultures with very different attitudes about race, religion, and the place of “savages.” Together they numbered over 750,000, and another 300,000 inhabited the other English-controlled colonies of the Atlantic seaboard.

15The leaders of Québec and Acadia could only hope that New England and Tidewater would remain what they had been from the outset: avowed enemies of one another with little in common beyond having come from the same European island.