CHAPTER 15

Yankeedom Spreads West

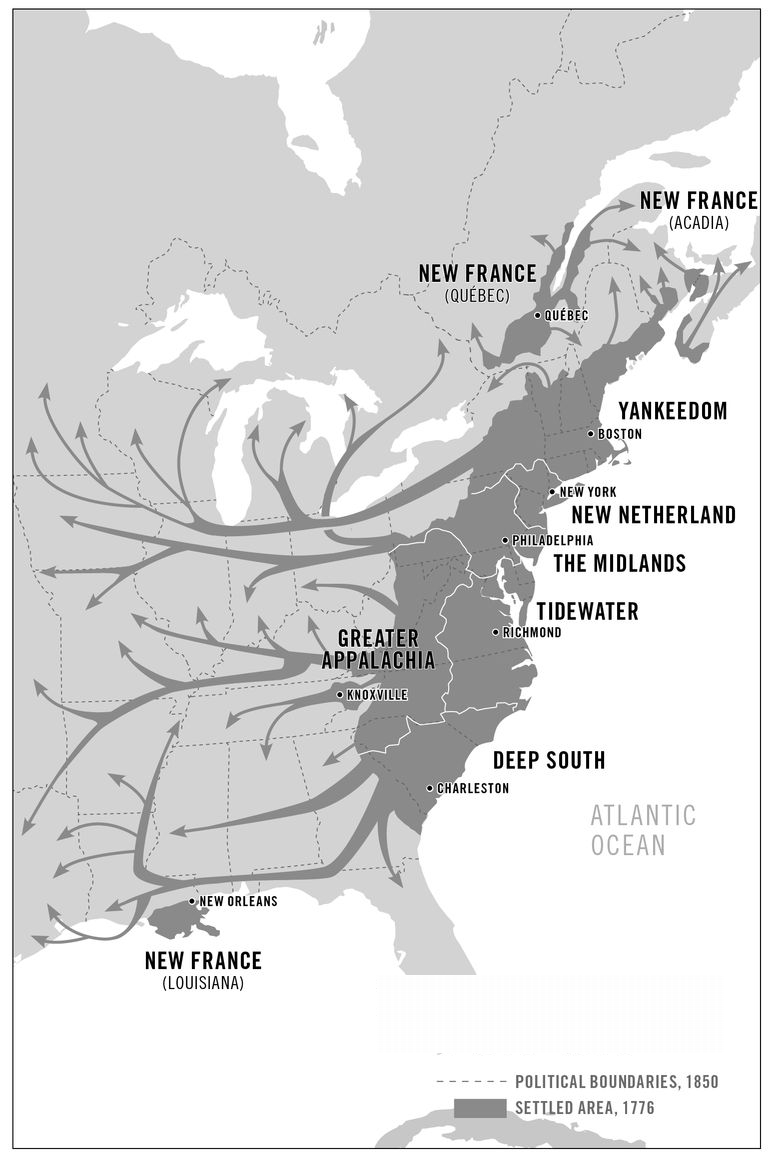

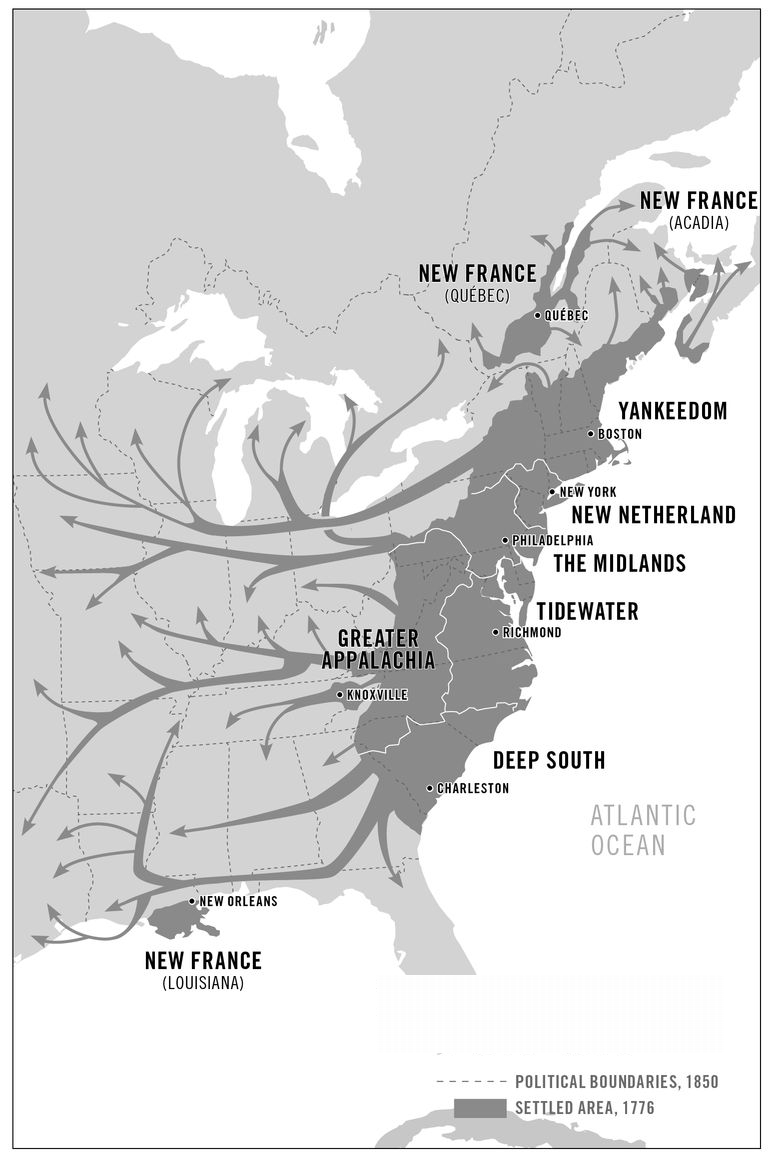

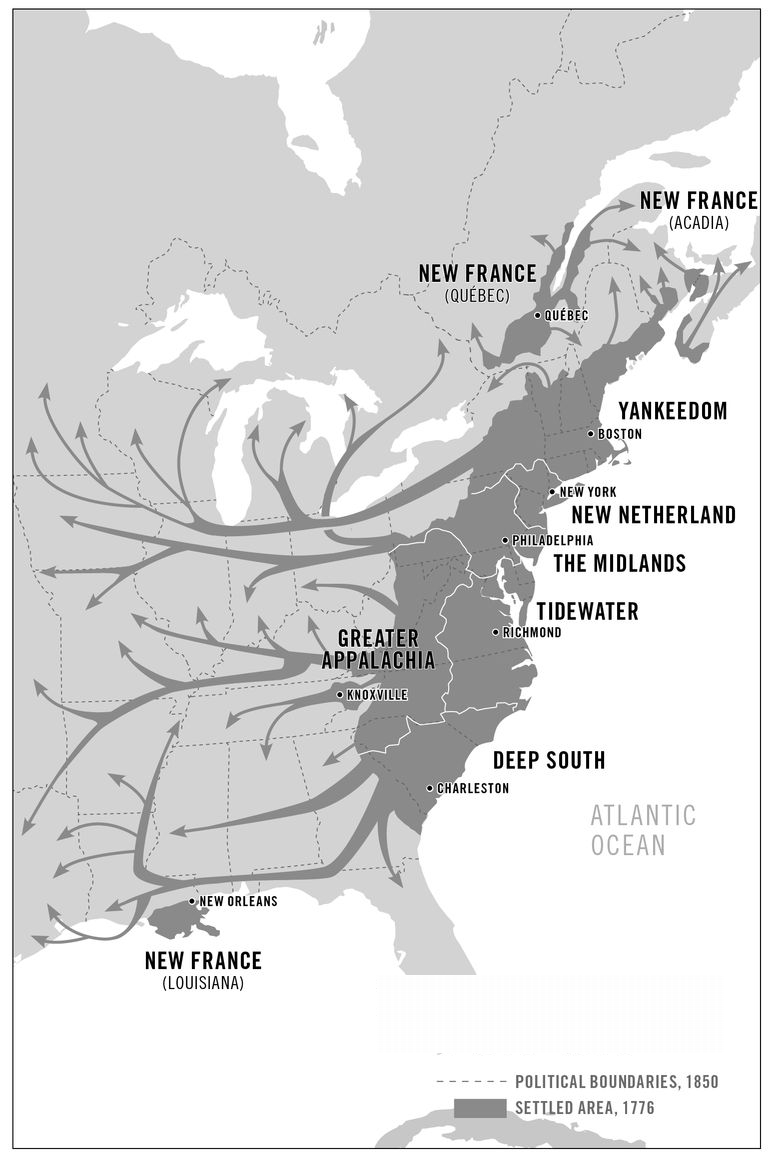

After the revolution, four of the American nations hurdled the Appa lachians and began spreading west across the Ohio and Mississippi valleys. There was very little mixing in their settlement streams, as politics, religion, ethnic prejudice, geography, and agricultural practices kept colonists almost entirely apart in four distinct tiers. Their respective cultural imprints can be seen to this day on maps created by linguists to trace American dialects, by anthropologists codifying material culture, and by political scientists tracking voting behaviors from the early nineteenth century straight through to the early twenty-first. With the exception of the New French enclave in southern Louisiana, the middle third of the continent was divided up among these four rival cultures.

New Englanders rushed due west to dominate upstate New York; the northern parts of Pennsylvania, Ohio, Illinois, and Iowa; and the future states of Michigan and Wisconsin. Midlanders poured over the mountains to spread through much of the American Heartland, characteristically mixing German, English, Scots-Irish, and other ethnicities in an ethnonational checkerboard. Appalachian people rafted down the Ohio River, dominating its southern shore, and conquered the uplands of Tennessee, northwestern Arkansas, southern Missouri, eastern Oklahoma, and, eventually, the Hill Country of Texas. Deep Southern slave lords set up new plantations in the lowlands of the future states of Florida, Alabama, and Mississippi; on the floodplains of the Big Muddy from northern Louisiana to the future city of Memphis; and, later, on the coastal plains of eastern Texas. Cut off from the west by their rivals, Tidewater and New Netherland remained trapped against the sea as the others raced across the continent, vying to define its future.

New England pushed west because of the shortcomings of its land. By the end of the eighteenth century, farmers were finding that the thin, rocky soils of much of Vermont, New Hampshire, and Maine were played out. In one of the continent’s most densely populated regions, the best farmland was already spoken for, and farmers’ younger children had to settle for ever-worsening prospects on the glacially scoured frontiers of eastern Maine. Even before the revolution, thousands had moved over the New York border and into northern Pennsylvania; afterward they flooded western New York in incredible numbers and drowned Dutch Albany and the upper Hudson Valley in a Yankee sea.

Their early efforts were supported by their political leaders, whose states laid claim to great swaths of New York, Pennsylvania, and what would become Ohio. Connecticut asserted its jurisdiction over the northern third of Pennsylvania, and its people even fought a now-forgotten war with Scots-Irish guerrillas for control of the area in the 1760s and 1770s. Connecticut settlers won the opening matches with the help of Scots-Irish mercenaries and a favorable ruling from King George I, and founded Wilkes-Barre and Westmoreland; after the revolution, the Continental Congress gave the region back to Pennsylvania, which tried to evict the Yankees by force. Connecticut and Vermont sent soldiers to help the settlers repel the attack, resulting in a final “Yankee-Pennamite War” in 1782. In the end Pennsylvania kept jurisdiction, but the settlers retained their land titles.

Similarly, Massachusetts laid claim to all of present-day New York west of Seneca Lake—six million acres in all—an area larger than Massachusetts itself. Based on contradictory royal grants, the claim was strong enough to compel New York to agree to a major compromise in 1786: the region would be part of the state of New York, but Massachusetts would own the property and could sell it at a profit. The result: settlement of much of the region was directed by Boston-based land speculators, and virtually all of its settlers came from New England. Traveling in the region in the early nineteenth century, Yale president (and Congregational minister) Timothy Dwight remarked on how much its towns looked like those in his native Connecticut and prophesied the Empire State would soon become “a colony from New England.” The towns of Yankee-settled areas such as Oneida and Onondaga counties in the west or Essex, Clinton, and Franklin in the north still look and vote much like their New England counterparts.

1

THE EASTERN NATIONS 1776–1850

The states had relinquished any jurisdictional claims to Ohio and the rest of the upper Midwest in 1786, when these former Indian lands became part of the federal government’s Northwest Territory. But Connecticut retained title to a three-million-acre strip of northern Ohio—its so-called Western Reserve—which was turned over to some of the same Boston speculators who had retailed out much of western New York. Another New England land company obtained a swath of the Muskingum Valley from the federal government. Both parcels were settled almost exclusively by Yankees.

True to form, the New Englanders tended to move west as communities. Entire families would pack their possessions, rendezvous with their neighbors, and journey en masse to their new destination, often led by their minister. On arrival they planted a new town—not just a collection of individual farms—complete with a master plot plan with specific sites set aside for streets, the town green and commons, a Congregational or Presbyterian meeting house, and the all-important public school. They also brought the town meeting government model with them. In a culture that believed in communal freedom and local self-governance, a well-regulated town was the essential civic organism and the very definition of civilization.

Yankee settler groups often viewed their journey as an extension of New England’s religious mission, a parallel to those undertaken by their forefathers in the early 1600s. The first group to depart Ipswich, Massachusetts, for the Muskingum Valley in 1787 paraded before the town meeting house to receive a farewell message from their minister modeled on the one the Pilgrims heard before leaving Holland. On the last leg of their journey, they constructed a flotilla of boats to float down the Ohio and named the flagship the

Mayflower of the West. Similarly, before setting out to found Vermontville, Michigan, ten families in Addison County, Vermont, joined their Congregational minister in drawing up and signing a written constitution loosely modeled on the Mayflower Compact. “We believe that a pious and devoted emigration is to be one of the most efficient means in the hands of God, in removing the moral darkness which hangs over a great portion of the valley of the Mississippi,” the settlers declared before pledging to “rigidly observe the holy Sabbath” and to settle “in the same neighborhood with one another” to re-create “the same social and religious privileges we left behind.” In Granville, Massachusetts, settlers drew up a similar compact before undertaking the journey to create Granville, Ohio.

2These New England outposts quickly dotted the map of the Western Reserve, their names revealing the origins of their Connecticut founders: Bristol, Danbury, Fairfield, Greenwich, Guilford, Hartford, Litchfield, New Haven, New London, Norwalk, Saybrook, and many more. Not surprisingly, people quickly started calling the region New Connecticut.

The Yankees consciously sought to extend New England culture across the upper Midwest. The emigrants aboard the

Mayflower of the West were typical. On arrival in eastern Ohio, they founded the town of Marietta, and happily imposed taxes on themselves to fund the construction and operation of a school, church, and library. Nine years after their arrival, they founded the first of the Yankee Midwest’s many New England–style colleges. Marietta College was headed by New England–born Calvinist ministers and dedicated to “assiduously inculcating” the “essential doctrines and duties of the Christian religion.” Also, “No sectarian peculiarities of belief will be taught,” the founding trustees decreed. Similar colleges popped up wherever the Yankees spread, each a powerful outpost of cultural production: Oberlin and Case Western Reserve (in Ohio), Beloit and Olivet (in Michigan), Ripon and Madison (in Wisconsin), Carleton (Minnesota), Grinnell (Iowa), and Illinois College.

3In this way, the Yankees laid down the cultural infrastructure of a large part of Ohio, portions of Iowa and Illinois, and almost the entirety of Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota. They had near-total control over politics in the latter three states for much of the nineteenth century. Five of the first six governors of Michigan were Yankees, and four had been born in New England. In Wisconsin, nine of the first twelve governors were Yankees, and all the rest were either New Netherlanders or foreign-born. (By contrast, in Illinois—where Midlands and Appalachian cultures were in the majority—not one of the first six governors was of Yankee descent; all had been born south of the Mason-Dixon line.) A third of Minnesota’s first territorial legislature was New England–born, and a great many of the rest were from upstate New York and the Yankee Midwest. In all three upper Great Lakes states, Yankees dominated discussions in the constitutional conventions and transplanted their legal, political, and religious norms. Across the Yankee Midwest, later settlers—be they immigrants or transplants from the other American nations—confronted a dominant culture rooted in New England.

4Nineteenth-century visitors often remarked on the difference between the areas north and south of the old National Road, an early highway that bisected Ohio and which is now called U.S. 40. North of the road, houses were said to be substantial and well maintained, with well-fed livestock outside and literate, well-schooled inhabitants within. Village greens, white church steeples, town hall belfries, and green-shuttered houses were the norm. South of the road, farm buildings were unpainted, the people were poorer and less educated, and the better homes were built with brick in Greco-Roman style. “As you travel north across Ohio,” Ohio State University dean Harlan Hatcher wrote in 1945, “you feel that you have been transported from Virginia into Connecticut.” There were exceptions (Yankees skipped over the marshlands of Indiana and northeastern Ohio en route to Michigan and Illinois), and between Appalachian “Virginia” and Yankee “Connecticut” one passed through a Midland transition zone. But the general observation holds true: the place we call “the Midwest” is actually divided into east-west cultural bands running all the way out to the Mississippi River and beyond.

5Foreign immigrants to the Midwest often chose where to settle based on their degree of affinity or hostility to the dominant culture, and vice versa. The first major wave was German, and, not surprisingly, many of them joined their countrymen in the Midlands. Those who did not faced a choice between the Yankees and the Appalachian folk; few opted to settle in areas controlled by the latter.

Swedes and other Scandinavians, for their part, were comfortable with the Yankees, with whom they shared a commitment to frugality, sobriety, and civic responsibility; a hostility to slavery; and an acceptance of a staterun church. “The Scandinavians are the ‘New Englanders’ of the Old World,” a Congregational missionary in the Midwest informed his colleagues. “We can as confidently rely upon them to help American Christians rightly [make] . . . ‘America for Christ’ as we can rely upon the good

old stock of Massachusetts.”

6Other groups who fundamentally disagreed with New England values avoided the region on account of the Yankees’ reputation for minding other people’s business and pressuring newcomers to conform to their cultural norms. Catholics—whether Irish, south German, or Italian—did not appreciate the Yankee educational system, correctly recognizing that the schools were designed to assimilate their children into Yankee culture. In areas where Catholic immigrants cohabitated with Yankees, the newcomers created their own parallel system of parochial schools precisely to protect their children from the Yankee mold. Yankees often reacted with hostility, denouncing Catholic immigrants as unwitting tools of a Vaticandirected conspiracy to bring down the republic. Whenever possible, Catholic immigrants chose to live in the more tolerant, multicultural Midlands or in individualistic Appalachia, where moral crusaders were looked upon as self-righteous and irritating. Even German Protestants found themselves at odds with their Yankee neighbors, who would try to pressure them into giving up their brewing traditions and beer gardens in favor of a solemn, austere observance of the Sabbath. Multiculturalism wouldn’t become a Yankee hallmark until much later, after Puritan values ceased to be seen as essential to promoting the common good.

7Political scientists investigating voting patterns have probed electoral records dating back to the early nineteenth century, matching pollingplace returns with demographic information about each precinct. The results have been startling. Previous assumptions about class or occupation being the key factors influencing voter choices have turned out to be completely wrong, with the nineteenth-century Midwest providing some of the most intriguing evidence that ethnographic origins trumped all other considerations from 1850 onward. Poor white German Catholic miners in northern Wisconsin tended to vote entirely differently from poor white English Methodist miners in the same area. English Congregationalists tended to vote alike regardless of whether they lived in cities or on farms. Scandinavian immigrants voted with native-born Yankees in opposition to candidates and policies preferred by immigrant Irish Catholics or native-born Southern Baptists of Appalachian origin.

8As the nation careened toward civil war in the 1850s, areas first settled by Yankees gravitated to the new Republican Party. Counties dominated by immigrants from New England or Scandinavia were the strongest Republican supporters, generally backed by German Protestants. This made Michigan, Wisconsin, and Minnesota reliably Republican straight through the mid-twentieth century; the other states split along national lines. Later, when the Republicans became champions in the fight against civil rights, Yankee-dominated states and counties in the Midwest flipped en masse to the Democrats, just as their colleagues in New England did. The outlines of the Western Reserve are still visible on a county-by-county map of the 2000, 2004, or 2008 presidential elections.

While much of the upper Midwest is indeed part of Greater Yankeedom, its greatest city is not. Chicago, founded by Yankees around Fort Dearborn in the 1830s, quickly took on the role of a border city, a grand trading entrepôt and transportation hub on the boundary of the Yankee and Midland Wests. New Englanders were influential early on, establishing institutions such as the Field Museum (named for Marshall Field of Conway, Massachusetts), the Newberry Library (for Walter Newberry of Connecticut), the

Chicago Democrat and

Inter Ocean newspapers, and the Chicago Theological Institute. But New Englanders were soon overwhelmed by new arrivals from Europe, the Midlands, Appalachia, and beyond. Purists fled north to found the very Yankee suburb of Evanston. Other Yankees looked disapprovingly upon the brash, unruly, multi-ethnic metropolis. By the 1870 census, New England natives comprised just one-thirtieth of the city’s population.

9

However assiduously New Englanders had set out to transform the frontier, they themselves were also transformed by it. Yankee culture may have maintained its underlying zeal to improve the world, setting it on the path toward the secular Puritanism of the present day, but it was stripped of its commitment to religious orthodoxy.

On the frontier, many Yankees would remain true to the Congregational faith or its near-cousin Presbyterianism, but others experienced a religious conversion. An essentially theocratic society, New England produced an unusual number of intense religious personalities—people, in the words of the late historian Frederick Merk, “eager to get into direct touch with God, to see God in person, to hear His voice from on high.” In the tightly controlled Yankee homeland, mystics and self-declared prophets generally were kept in check, but out on the frontier, the enforcement of orthodoxy was laxer. The result was an explosion of new religions, starting in western New York, where religious fervor was so incendiary that people started calling it the “Burnt-over District.”

10Many religions came into being, but nearly all of them sought to restore the primitive simplicity of the early Christian faith before it accreted elaborate institutions, a written canon, and a bevy of clerical authorities. If Lutherans, Calvinists, or Methodists had sought to bring people closer to God by eliminating the upper levels of ecclesiastical hierarchy (archbishops, cardinals, and the Vatican), these new evangelicals took things several steps further, removing the middle ranks almost entirely. People were to contact God directly and personally, and would become born again when they did so. They were to seek their own path to the divine, guided by one or more trailblazers who allegedly enjoyed unusually good communication with their maker. Like the prophets, these charismatic leaders believed they had been personally contacted by God and shown the true path to salvation.

On the Yankee frontier, God apparently handed out conflicting instructions. William Miller, a farmer born in Massachusetts and raised on the Vermont frontier, announced that Christ was to return, cleanse, and purify the Earth in 1843. When this failed to occur, he recalculated the date to October 22, 1844, setting his tens of thousands of followers up for an event known as the Great Disappointment. The movement’s adherents still await the second coming, worshipping on Saturdays and emphasizing a diet featuring cold grains and cereals. (They’re now known as the Seventh-Day Adventists and number over a million members.) John Humphrey Noyes, a Yale-educated Vermonter, decided the second coming had already occurred and, having declared himself “perfect and free of sin,” led his followers to create a utopian society in upstate New York; intended as a model for Christ’s millennial kingdom, Noyes’s Oneida Community featured communal manufacturing, property ownership, and sexual relations, with older men and postmenopausal women encouraged to deflower the virgins. Vermont farmer Joseph Smith and his son were among hundreds of “divining men” who claimed special abilities to find buried treasures and dispel the charms protecting them, services they were paid in advance to perform. After being arrested for defrauding his clients, Joseph Smith Jr. found a set of golden plates in a hillside in Manchester, New York (others were not allowed to see them), which revealed to him (in a language only he could read) that Jesus would return to Independence, Missouri. Tens of thousands were drawn to his polygamous millennial kingdom in Nauvoo, Illinois, which tried to secede from the state to become a separate U.S. territory. After Smith’s assassination, his followers moved to Utah and, as the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, now number over 5 million. These and kindred utopian movements on the Yankee frontier had a dramatic effect on future developments on the continent.

11Across Yankeedom the official Congregational and Presbyterian churches were also losing adherents to rival denominations, shattering religious homogeneity. Some New England congregations embraced Unitarianism (the belief in a unitary God as opposed to a holy trinity), and some of those moved on to Unitarian Universalism, which holds that each individual is free to search for his own answers to the great religious and existential questions. Far more Yankees shifted to Methodism, an eighteenth-century splinter from the Anglican Church with an emphasis on effecting social change, or, following in the footsteps of Rhode Island’s founders, became Baptists, who believed in salvation through faith alone. This amounted to a major shift in Yankee religious heritage, and was deplored by Congregational authorities. Lyman Beecher, perhaps the most influential mid-nineteenth-century Yankee theologian, decried Baptists and Methodists as “worse than nothing” and Unitarians as “enemies of the truth.”

12While religious orthodoxy in New England was undermined during the nineteenth century, the deep-seated Yankee belief that it was possible to make earthly society resemble God’s kingdom above remained intact. Lyman Beecher and other members of the orthodox elite would fight a ferocious rearguard action against the insurgents, but the effort was ultimately futile. The Yankee moral project was by no means over, however. Its greatest battles lay just ahead and would be waged against its rival nations to the south.