In its essence, the Ottoman state was a dynastic one, administered by and for the Ottoman family, in cooperation and competition with other groups and institutions. In common with polities elsewhere in the world, the central dynastic Ottoman state employed a variety of strategies to assure its own perpetuation. It combined brutal coercion, the maintenance of justice, the co-option of potential dissidents, and constant negotiation with other sources of power. This chapter examines some of the obvious as well as the more subtle techniques of rule that it employed to domestically project its power over the centuries. Significantly, it explores the actual power of the central government in the provinces. It suggests that the older narratives stressing an extensive amount of administrative centralization are overstated.

At the heart of Ottoman success lay the ability of the royal family to hold onto the summit of power for over six centuries, through numerous permutations and fundamental transformations of the state structure. Therefore, we first turn to modes of dynastic succession and how the Ottoman dynasty created, maintained, and enhanced its own legitimacy.

Globally, royal families have used principles of both female and male or exclusively male succession. In common with early modern and modern monarchical France (where the Salic law prevailed), but unlike the modern Russian and British states, the Ottoman family used the principle of male succession, considering only males as potential heirs to the throne. Many dynasties employed a second principle of succession, primogeniture, by the eldest son of the ruler. The Ottoman dynasty departed sharply from the usual inheritance practices for almost all of its history. From the fourteenth through the late sixteenth centuries, the dynasty employed a brutal but effective method of hereditary succession – survival of the fittest, not eldest, son. From an early date, following central Asian tradition, reigning sultans sent their sons to the provinces in order to gain administrative experience. There, as governors, they were accompanied by their retinues and tutors. (Until 1537, various Ottoman princes also served as military commanders.) In this system, all sons possessed a theoretically equal claim to the throne. When the sultan died, a period between his death and the accession of the new monarch usually followed, when the sons jockeyed and maneuvered. Scrambling for power, the first son to reach the capital and win recognition by the court and the imperial troops became the new ruler. This was not a very pretty method; nonetheless it did promote the accession of experienced, well-connected, and capable individuals to the throne, persons who had been able to win support from the power brokers of the system.

This method of succession changed abruptly when Sultan Selim II (1566–1574) sent out only his eldest son (the future Murat III, 1574–1595) to a provincial administrative post, Manisa in western Anatolia. Murat III in turn sent out only his eldest son (the future Mehmet III, 1595–1603), again as governor of Manisa. Mehmet III in fact was the last sultan who actually administered as a governor (for another fifty years, eldest sons were named as governors of Manisa but never served). Thus, during those reigns, the Ottomans de facto conformed to the practice of primogeniture.

During part of the time that survival of the fittest operated as a principle of succession, so too did the bloody practice of fratricide. Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror (1451–1481) was the first to employ fratricide, ordering the execution of all his brothers. This requires some explanation since Ottoman society and Islamic societies in general vigorously condemned murder (as did contemporary Christian Europe). Yet in both Europe and the Middle East, an act that would have been immoral if committed by an individual person was permissible to rulers. Private persons couldn’t murder but rulers could. Here, clearly, is the face of raison d’état. Machiavelli would have recognized himself in the following regulation (kanun-name) that Sultan Mehmet issued to justify his fratricidal actions: “And to whomsoever of my sons the Sultanate shall pass, it is fitting that for the order of the world he shall kill his brothers. Most of the Ulema allow it. So let them act on this.”1 Thus, private individuals could not kill but the ruler could murder, even his own brothers, for the sake of order and stability in the realm. For more than a century, the practice of fratricide continued and, in 1595, after gaining the throne, Mehmet III ordered the execution of his nineteen brothers! The custom of fratricide really ended in 1648; thereafter, it happened only once again. In 1808, Sultan Mahmut II executed his brother, the only other surviving male, Mustafa IV, in order to preserve his own rule.

As the dynasty abandoned fratricide, it also shifted away from survival of the fittest to succession by the oldest male of the family. This practice (called ekberiyet) began in 1617 and prevailed to the end of the empire. Accordingly, on the death of the sultan, the oldest male – often an uncle or brother of the deceased sultan – assumed the throne. As succession of the eldest developed, the “gilded cage” (kafes) system began, in 1622. When the eldest male became sultan, the rest of the males were allowed to live, to assure continuity of the royal family. Accordingly, princes were kept alive, not actually in a cage but rather within the palace grounds, particularly the harem, where they were shielded from public view and under the eye and control of the reigning sultan. The royals, however, rarely received any administrative education or experience; typically but not always, time in the cage was not devoted to preparation for eventual rule. Moreover, only a reigning ruler was allowed to beget children. Sultan Mehmet III was the last ruler who, as prince, fathered children. Rule by the eldest male meant that a potential ruler might wait a long time in the cage before becoming sultan: thirty-nine years is the record. During the nineteenth century, those who ruled typically waited fifteen years and longer before ascending the throne.

It is crucial to connect these changes in the succession practices – survival of the fittest, fratricide, and rule of the eldest – to our earlier discussions of where power actually rested at particular moments in Ottoman history. The radical step of fratricide emerged just when the sultans had shed their status as primus inter pares, having won their long power struggles against the Turcoman notables and border beys. The later sixteenth-century policy shift from sending all the sons to just the eldest one, in order to acquire administrative experience, occurred as power was passing out of the personal hands of the sultan to that of his court. The adoption of rule of the eldest and the cage system, in turn, coincided with the transition of power away from the palace to the vizier and pasha households. Thus, Ottoman principles of dynastic succession changed along with the locus of power from the aristocrats, to the sultan, to his household, and then to the households of viziers and pashas. Sultans were needed less and less as warriors or administrators but remained essential as symbols and legitimators of the ruling process itself. The royal women played an indispensable role in maintaining and building alliances throughout the Ottoman elite structures and often were key players in the wielding of political power. In a sense it was irrelevant that so many sultans were deposed – nearly one-half of the total – since their position but no longer their person functioned as the indispensable component in the working of the system. In other words, sultans were needed to reign: ruling became the prerogative of others.

As the actual or symbolic leaders of the Ottoman state, the sultans employed a host of large and small measures to maintain their hold over Ottoman society and the political structure. The many daily reminders of their presence which they carefully and continuously offered suggests that their power derived not merely from the troops and bureaucrats they commanded but also from a constant process of negotiation between the dynasty, its subjects, and other power holders, both in the center and the provinces.

The Ottoman rulers used a host of legitimizing instruments to enhance their position, ranging from public celebrations of stages in the lifecycle of the dynasty to good works. At the moment a new sultan ascended the throne, an acknowledgment ceremony was held inside the Topkapi palace complex, where most Ottoman sultans resided between the fifteenth and nineteenth centuries. The new ruler then proceeded to the Imperial Council (Divan), presented gifts to this inner circle and ordered the minting of new coins, a royal prerogative. Within two weeks, a vital ceremony – the girding of the sword of Osman, the dynastic founder – took place at the tomb complex at Eyüp, on the Golden Horn waterway in the capital city. With much pomp and circumstance, the sultan left the palace and boarded a boat for the short journey up the Golden Horn. The tomb complex commemorated a companion of the Prophet Muhammad named Eyüp Ansari, who had died before the walls during the first Muslim siege of Byzantine Constantinople, 674–678. In 1453, the troops of Sultan Mehmet the Conqueror miraculously found the body of Eyüp and, on the spot, the sultan erected a tomb, mosque, and attendant buildings. On these sacred grounds occurred the sword girding, the Ottoman coronation, that linked the present monarch both to his thirteenth-century ancestors and to the very person of the Prophet.

The circumcision of a sultan’s sons marked another milestone event in the lifecycle of the dynasty since it represented the successful coming of age of the next generation of royal males. Over the centuries, sultans celebrated these events with fireworks, parades, and sometimes very lavish displays. Frequently, to associate their own sons with those of the general populace, the dynasts, including Ahmet III in the early eighteenth century and Abdülhamit in the late nineteenth century, paid for the circumcision of the sons of the poor and other residents of the capital. In 1720, Sultan Ahmet III held a famous sixteen-day holiday for the circumcision of his sons, celebrated in Istanbul and in towns and cities across the empire. The Istanbul event included the circumcision of 5,000 poor boys as well as processions, illuminations, fireworks, equestrian games, hunting, dancing, music, poetry readings, and displays by jugglers and buffoons.

This same sultan, in 1704, held grand festivals to celebrate the birth of his first daughter, an event that recognized women’s leadership role in the politics of the royal family.2 In other ceremonies, the dynasty linked itself to the spiritual and intellectual elite of the state. For example, in the late seventeenth century, young Mustafa II’s formal education under the tutelage of the religious scholars (ulema) was celebrated in a ceremony that demonstrated his memorization of the first letters of the alphabet and sections of the Quran. On other occasions, sultans sponsored reading competitions among leading ulema, thus further associating themselves with the intellectual life of these scholars.

Other devices weekly and daily reminded subjects of their sovereign and of his claim on their allegiance. Every Friday, at the noon prayer, the name of the ruling sultan was read aloud in mosques across the empire – whether in Belgrade, Sofia, Basra, or Cairo. Thus, subjects everywhere acknowledged him as their sovereign in their prayers. In the capital city, Sultan Abdülhamit II (1876–1909) marched in a public procession from his Yildiz palace to the nearby Friday mosque for prayers, as his official collected petitions from subjects along the way. Subjects were reminded of their rulers in the marketplace and whenever they used money. Ottoman coins celebrated the rulers, noting their imperial signature, accession date and, often, the regnal year. During the nineteenth century, new devices appeared to remind subjects of their rulers’ presence. Postage stamps appeared, imprinted with the names and imperial signatures of the ruler and even, in the early twentieth century, a portrait of the imperial personage himself, Sultan Mehmet V Reşat (1909–1918). And, after the appearance of newspapers, large headlines and long stories proclaimed important events in the life of the dynasty, such as the anniversary of the particular sultan’s accession.

In earlier times, artists had celebrated a sultan’s prowess in paintings, depicting his victories in battle or otherwise courageously on the hunt or in an archery display. While these are familiar motifs well into the seventeenth century, the palace workshops producing them vanished, perhaps because the sultans were less heroic and more palace bound. The purpose and effect of such paintings, usually placed in manuscripts, is uncertain since, after all, they remained within palace walls, viewed by only the palace retinue.

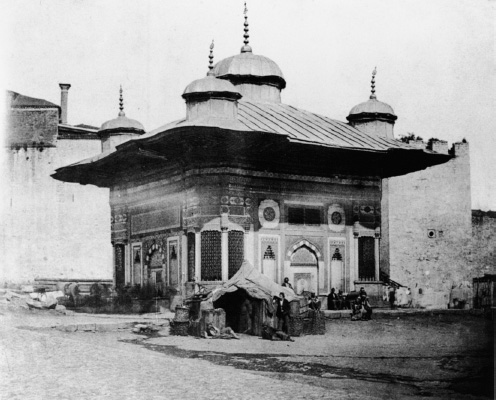

Plate 1 Fountain of Sultan Ahmet III (1703–1730), Istanbul

Personal collection of author.

The dynasty, using its personal funds, constructed hundreds upon hundreds of buildings for public use, all of them serving to remind subjects of its beneficence. Recall here that rich and powerful persons, not the state, provided for the institutions of health, education, and welfare until the later nineteenth century, when the transforming Ottoman state assumed this responsibility. Sultans and members of the royal family over the centuries routinely financed the building and maintenance of mosques, soup kitchens, and fountains – often in the capital but also everywhere in the empire. They financed these not from state monies but their own private purses (until the nineteenth century, however, the treasury of the sultan and of the state were really not distinguishable). They did so as pious acts and also to reaffirm their right to rule and thus retain the approval, gratitude, and finally obedience of the subject populations. Sultan Ahmet III, in 1728, financed the building of a grand fountain, outside of the first gate of the imperial Topkapi palace (plate 1). In the distant small town of Acre in northern Palestine, Sultan Abdülhamit II constructed a clocktower for the local population and placed his name on it as a reminder of his generosity. Also, during his reign, this sultan engaged in philanthropy to an unprecedented extent, widely distributing small-scale charitable contributions as a means of reinforcing the loyalties of his (presumably) grateful subjects. Sultans also financed the extraordinary imperial mosques that still dominate the skyline of Istanbul and other former Ottoman cities, for example, the sixteenth-seventeenth century Istanbul mosques of Süleyman the Magnificent and of Ahmet I and of Selim II in Edirne – taking care to name these after themselves. Thus, the dynasty inextricably was linked to the greatest places of worship in the Ottoman Muslim world. In the nineteenth century, Sultan Mahmut II continued this tradition, naming his newly built (1826) mosque “Victory” (Nusretiye) to commemorate his recent annihilation of the Janissary corps (plate 2). Royal energies and monies went in many other directions as well, for example, to build and support hundreds of bridges, fountains, and inns for travelers across the empire.

The sultans, who professed and maintained Sunni Islam, also took care to address the needs of their Shii Muslim subjects, competing with the Safevids to decorate the Karbala and Nejef shrines (that commemorated crucial events in Shii Islamic history) during the later sixteenth century, and continuing such support later on. In addition, the dynasty energetically asserted its physical presence in the Holy Cities of Mecca and Medina, reminding all of the connection between the dynasty and the Holy Places. There, prominent inscriptions proclaimed Ottoman largesse in repairing structures already nearly a millennium old, giving the dynasty a prominent place in the life of these Holy Places that it jealously guarded. In the late nineteenth century, for example, Sultan Abdülhamit II prevented other Muslim rulers from decorating the Holy Places, just as his predecessors had competed with the Moghul emperors in the sixteenth century. Similarly, the Ottomans sought to monopolize the provisioning of the local population in Mecca. The sultans also took considerable pains to assure the safety of the pilgrims traveling to Mecca and Medina to fulfill the sacred duties. As Ottoman military power continued to weaken, the regime emphasized its identity as a Muslim state in an unprecedented manner. As seen (chapter 5), the title and role of caliph began to emerge as an instrument of international politics in the later eighteenth century. During the first half of the eighteenth century, the sultans began taking particularly careful measures to protect and fortify the pilgrimage route from Damascus to the Holy Cities, building forts and bolstering garrisons. Wahhabi revolutionaries from Arabia, deliberately seeking to undermine Ottoman legitimacy, disrupted the pilgrimage during the eighteenth century and, in 1803, captured Mecca itself. Sultan Mahmut II then asked Muhammad Ali Pasha in Egypt to send his own troops, who temporarily broke Wahhabi power. Abdülhamit II, to enhance his caliphal title, facilitate pilgrims’ travel, and bind the Syrian–Arabian provinces to Istanbul, built the Hijaz Railroad at the end of the nineteenth century. During World War I, British efforts to capture Mecca and Medina and disrupt the railroad aimed to undermine Ottoman prestige in the larger Islamic world, as had the Wahhabi attacks more than a century before (see chapter 5).

Plate 2 Interior view of Nusretiye (Victory) Mosque of Sultan Mahmut II (1808–1839)

Personal collection of author.

And yet, no reigning Ottoman sultan ever made the pilgrimage and visited the Holy Cities. Indeed, fewer than half a dozen members of the dynasty ever performed the pilgrimage.3 Four were royal women, several of them wives of sultans. While in Cairo in 1517, Sultan Selim I received the keys to the Holy Cities from the Sharif of Mecca but, although quite nearby, did not visit the sacred places. In the early seventeenth century, Sultan Osman II announced his intent to make the pilgrimage but soon thereafter was killed. Shortly after his deposition in 1922, Sultan Mehmet VI Vahideddin visited Mecca, perhaps the only male Ottoman ever to have done so, but withdrew before performing the pilgrimage rites. How are we to understand this dynastic neglect of such a fundamental duty, one incumbent on all Muslims with suitable health and finances? In the time of Sultan Osman II, the ulema issued a formal religious opinion, saying that sultans needed to stay at home to dispense justice rather than leave the capital to go on pilgrimage.4 At the time, the ulema opposed his rule and feared that Osman might have a secret agenda in planning a pilgrimage. So, this opinion in favor of a sultan not making the pilgrimage may have been quite idiosyncratic. In the end, the absence of the dynasty from the pilgrimage seems remarkable.

The Topkapi palace – residence of sultans from the fifteenth until the mid-nineteenth century – loomed as a closed place of power and mystery, projecting the awesome majesty that the dynasty sought to convey. It was a forbidden city, not dissimilar from that in Beijing but on a smaller scale. It was built as a series of concentric circles, one inside the other, with increasingly restricted access as persons passed through gates from the outer to the inner circles. The general public entered through the main gate of the palace into the first courtyard but no further. Those on official business passed into the second court to present matters before the imperial council (Divan), but no further. The third court was reserved for officials only while other sections were exclusively for the sultan, the royal family, and the necessary personal servants and retainers. As the state structures changed, so did the palaces. The Tanzimat sultan Abdülmecit abandoned Topkapi in 1856 for his extravagantly open Dolmabahçe Palace on the Bosphorus shores. The Yildiz palace of Sultan Abdülhamit II, further up the Bosphorus, in turn reflects that monarch’s more private and reclusive nature.

Resting within the Topkapi palace (to this day) are sacred relics, the possession of which was intended to bring dignity and honor to their Ottoman guardians. Brought from Cairo in 1517 by Sultan Selim I, these included the mantle of the Prophet, hairs from his beard, his footprint, and other sacred objects, such as his bow. Also present are the swords of the first four caliphs of Islam. Significantly, the relics are situated inside the palace, a seat of political power. Here we have no less than the equivalent of a European monarch proudly owning a piece of the body of John the Baptist, or of the True Cross which the Byzantine emperor allegedly had found and brought to Constantinople.

The devşirme method of recruiting administrators and soldiers – the “child levy” – was long gone by 1700 but deserves discussion here for the light it sheds on the stereotyping that remains all too prevalent in popular perceptions of the Ottoman past. The stereotype overemphasizes the importance of the devşirme and asserts that Christian converts to Islam were responsible for Ottoman greatness. As most overgeneralizations, this stereotyping emerges out of some realities. During the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, devşirme conscripts indeed were an important source of state servants and many became grand viziers and other high administrators. Gradually, however, the devşirme was abandoned. Sultan Osman II tried to abolish it in 1622, indicating that it was becoming obsolete and dysfunctional. His successor, Sultan Murat IV, suspended the levy and it essentially had disappeared from Ottoman life by the mid-seventeenth century. The stereotyping comes from the coincidence of this diminishing use of the levy with another fact, namely, that the empire was declining in military power during these same years.

In fact, there are several false assumptions present here: the first surrounds the role of changes in domestic political structures in the observable weakening of the Ottoman Empire after c. 1600. For many years, observers falsely concluded that the evolution of the domestic institutions, the shift in power away from the sultan, caused the weakening of the empire in the international struggle for power. Historians, however, now have concluded that domestic political structures in the Ottoman Empire were undergoing change between the sixteenth and the eighteenth centuries, a process that is better described as the evolution of Ottoman institutions into new forms. In their new forms, the institutions certainly differed from those of the past: sultans now merely reigned while viziers and pashas actually ran the state. But these differences in domestic institutions constituted a transformation, not a weakening, between the sixteenth and eighteenth centuries. The charges of weakness and decline stem from the international front where the Ottomans indeed were losing wars and territories. Internationally, the Ottoman system of 1750 was certainly less powerful than it had been in 1600; the relative international position of the empire had fallen quite sharply. Here is the real story of decline. Falling further and further behind Europe, the Ottomans shared a fate with the entire world but for Japan (and its rise of world power after 1853). The west (and some east and central) European states had become immeasurably stronger; the Ottoman Empire, which c. 1500 had been among the most powerful, fell to second-rank status during the eighteenth century. The transfer of power out of the sultan’s hands occurred at the same time as but did not cause this international decline.

The second false assumption revolves around the now abandoned notion that the source of Ottoman state strength had been the (converted) Christians running it. When the devşirme faded, the argument went, so did the power of the state because Muslims and no longer the ex-Christians now were in charge. In this argument, the conclusion is drawn, quite mistakenly, that the one caused the other – Ottoman greatness derived from the devşirme and its abandonment triggered the decline of the Ottoman Empire. In this blatant example of cultural and religious prejudice, Christians are seen as innately superior to Muslims who falsely are seen as incapable of managing a state.

The decline of the devşirme and the transformation of the Ottoman state – which both occurred between c. 1450 and 1650 – more productively can be considered as a function of the dynamics of the Ottoman political system in two distinct but related ways. First of all, the early Ottoman state exhibited an extreme social mobility, with few barriers to the recruitment and promotion of males. Growing rapidly, the state military and administrative apparatus desperately needed staffing and offered essentially all comers the opportunity for wealth and power. As a part of that fluid process, the devşirme brought in recruits fully dependent (theoretically) on the ruler, at least during the first few generations. Over time, the growing ranks of state servants were drawn from a number of sources. Some derived from the first generation of devşirme recruits; others came from the descendants of recruits from earlier generations who had aged in Ottoman service, fathered families, and arranged for the entry of their sons into the military or bureaucracy; and, third, there were many soldiers and bureaucrats who had entered via other channels, for example, the households of Istanbul-based viziers and pashas. Over time, the latter two groups numerically increased in importance; that is, as the political system matured, it furnished its own replacements from within, rendering the devşirme unnecessary.

Second, consider the gradual abandonment of the devşirme as a part of the process in which power shifted away from the person of the sultan, to his palace, and then to the vizier and pasha households of Istanbul, respectively during the periods c. 1453–1550, 1550–1650, and after 1650. Since only sultans had access to the recruits of the devşirme system, its decline derived from the sultans’ loss in power within the system. This shift away from the devşirme and from the education of recruits in the sultanic palace already was visible in the mid-sixteenth century, at the height of the sultan’s personal power. At that time, some state servants already were training palace pages in their own households; these later entered the imperial household and subsequently became high-ranking provincial administrators (sancakbeyi or beylerbeyi). In the seventeenth century, young men more usually entered palace service via patrons who were ranking persons in the civil or military service. Thus, the devşirme and palace system declined and households of viziers, pashas, and high level ulema arose with organizational structures closely resembling the sultan’s household. These latter, however, could not recruit devşirme – a sultanic prerogative – and instead recruited young slaves or the sons of clients, or allies, or others wanting to enter. Such vizier, pasha, and high ulema households slowly gained prominence, providing persons with varied experiences in the many military, fiscal, and governing responsibilities needed for administrative assignments. Offering recruits with more flexible and varied backgrounds than the devşirme, they successfully competed with the palace. By the end of the seventeenth century, vizier–pasha household graduates held nearly one-half of all the key posts in the central and the provincial administration.

To shore up their own power throughout the eighteenth, nineteenth, and twentieth centuries, the sultans routinely married their royal daughters, sisters, and nieces to important officials in state service. In this way, they maintained alliances and reduced the possibility of rival families emerging. Sometimes the daughters were adults and on other occasions infants or young children. Often, when the husbands died, the royal women quickly remarried, allying with another ranking official, thus continuing to help the dynasty. Marriage alliances continued as standard dynastic practice until the end of the empire. For example, in 1914, a niece of the reigning sultan married the powerful Young Turk leader Enver Pasha.5

The present section offers two different geographic examples of the relationship between the capital and the provinces during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries: the first from Damascus, 1708–1758, and the second from Nablus, in northern Palestine, c. 1798–1840. While both examples are drawn from the Arab provinces, they are intended to be illustrative of the empire as a whole, suggesting the complex processes of constant negotiation between imperial and local officials.

By way of background to the Damascus example, first recall the general flow of events during the eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries. In the international arena, until c. 1750, the central state enjoyed some successes on the battlefield, winning back the Morea, defeating Peter the Great and then the Venetians, and regaining the fortress center of Belgrade. Thereafter, disasters ensued, notably the Ottoman–Russian War of 1768–1774 and the defeats at the hands of Russia and Muhammad Ali Pasha during the 1820s and 1830s. In the domestic political area, Istanbul early in the eighteenth century enacted some vigorous programs to gain better control of the provinces, only to yield more power to the local notables after c. 1750. In this latter period, Istanbul gave its provincial governors more discretion, increasingly relying on notables as intermediaries with the populace. Throughout the eighteenth century, however, shared financial benefits bound together the interests of the central and provincial authorities. And then, near the turn of the nineteenth century, important changes in the visible instruments of control began to occur. Sultan Selim III and, more successfully, Mahmut II, began to amass power at the center and build a more centralized political system that sought greater control over day-to-day life in the provinces.

Also, we need to touch upon the territorial divisions of the empire. In the early centuries, Ottoman lands had been divided rather simply into two great administrative chunks – the beylerbeyliks of Anatolia (the Asian areas) and that of Rumeli (the Balkans), each under the eye of a beylerbeyi, with subdivisions of districts (sancaks). By the sixteenth century, the administrative system that, speaking very generally, prevailed until the end, was in place. Provinces constituted the major administrative divisions, each with its own districts (sancaks) and sub-districts (kazas). In each unit were a variety of officials, each reporting upwards through the chain of command, finally to the provincial governors at the top of the pyramid. Generally, this administrative pattern prevailed until the end of the empire although, while the names remained the same, the size of each administrative unit decreased over time (map 6).

Damascus was a key Ottoman place and for this reason it became a center of Istanbul’s attention during the first half of the eighteenth century. The story begins in 1701, following massive Ottoman defeats on the European frontier and a disaster in which 30,000 pilgrims on the Damascus–Mecca pilgrimage route died in bedouin attacks. Thus, the Treaty of Karlowitz and the destruction of the pilgrimage caravan made the need for change shockingly clear, both locally and in the center.

Istanbul then moved to revitalize the administration of Damascus in a number of ways. First, it entrusted the governor of Damascus with a number of powers that it previously had spread around among the various provincial administrators – granting him the right to collect taxes, maintain security, prevent revolts, and maintain urban life. The governor was to restore harmony to the Ottoman system, better protecting the subject populations so that they, in turn, could better finance the state and its military. In common with contemporary states everywhere, the Ottoman state’s basic task was to assure a prosperous population in order to support the army which in turn defended the population.7 Second, the capital dispatched a new governor in 1708, who originated in Damascus and possessed strong local connections, a member of the al-Azm family (which to the present has retained an influential voice in Damascene and Syrian politics). At the time of his appointment, he was recognized both as a part of the imperial elite in Istanbul and also of the local elite in Damascus. His connections to Istanbul were crucial and the capital considered the al-Azm appointee as its instrument. The al-Azms for their part pursued their own local interests but also functioned as part of an Ottoman circle, needing the patronage and protection of Istanbul to maintain their hold as governors. These Damascus events reflected part of a larger pattern in which the central state no longer generated its own elites to rule over the provinces but co-operated with local elites, sending them back to their home area to rule, on behalf of the central state. Thus, the al-Azm appointment marked the continuing evolution of Ottoman administration and the growing importance of local connections over palace training.

Map 6 Ottoman provinces, c. 1900

Adapted from Halil İnalcık with Donald Quataert, eds., An economic and social history of the Ottoman Empire, 1300–1914 (Cambridge, 1994), xxxix.

This appointment represents other administrative changes as well, to turn to our third point. After 1708, the governor of Damascus no longer needed to serve in imperial wars and bring troops under his command to the frontiers. This redefinition of responsibility reflected the new eighteenth-century realities of an empire no longer expanding territorially and seizing new revenues. Rather, it acknowledged the new need to consolidate and more effectively exploit existing resources. Without military service, the governor thus lost an important path of promotion. Now marked as an administrator rather than warrior, the governor possessed more direct control and authority over a larger part of the province than ever before. Primarily sworn to keep law and order at the local level, and explicitly ordered not to go away on campaign, the governor became a localized figure in a novel and profound way. As a corollary, the rotation of governors in the empire overall decreased sharply in the early eighteenth century, an indication of the emphasis being placed on their successful discharge of local duties.

Four, with his knowledge of local conditions, the new governor, as part of Istanbul’s effort to prevent the growth of autonomous structures in the provinces, sought to create more effective checks and balances among local notables, Janissary garrisons, bedouins, and tribes. He achieved this in a number of ways, including manipulation of the local judiciary. Ottoman law recognized four schools of Islamic law but the state officially had adopted the Hanafi rite. In Damascus, ulema of the Hanafi school increasingly obtained favor at the expense of the Damascus religious establishment, which followed the locally more prevalent Shafii school. Indeed, while the Damascus ulema until c. 1650 derived from the Shafii, Hanafi, and Hanbali schools of law, almost all were Hanafi by 1785. In this way, the state aimed to create a more homogeneous legal administration, more in line with principles being followed in Istanbul.

Fifth, the new governor acted to create greater safety for the haj pilgrims, a task given a much higher priority than in the past. And so he posted more garrisons, provided stronger escorts, and built more forts along the route to the Holy Cities. After 1708 and until 1918, the Damascus governor served officially as commander of the pilgrimage, part of the greater imperial commitment to solving problems within the region as well as to raising the profile of the state in matters of religion.

These programs of closer central control in Damascus province more or less worked until 1757, when bedouins plundered the returning pilgrimage and 20,000 pilgrims died of heat, thirst, and the attacks. This ended, until the nineteenth-century reforms, centralization efforts in the area of Damascus. Thereafter, local notables rose to greater prominence in the area. Famed among them, Zahir ul Umar launched and Jezzar Pasha further expanded a mini-state in the area from north Palestine to Damascus. (Jezzar Pasha’s beautiful mosque can still be seen in Acre, as can the nearby aqueducts that he built to boost Palestinian cotton production for sale to Europe.) Similarly, powerful provincial notables emerged almost everywhere during the later eighteenth century. For example, the Karaosmanoğlu ruled west Anatolia for most of the eighteenth century while, near modern-day Albania, Tepedelenli Ali Pasha controlled the lives of 1.5 million Ottoman subjects.8

Unlike Damascus, Nablus was not an important center but rather a hill town of modest regional significance. The Nablus story has two parts: the first centering on the period c. 1800 and the second dating from the 1840s. In its first part, we learn much about the nature of provincial life in many regions during the later eighteenth century when notable autonomy reached new levels and the writ of the central state sometimes was scarcely felt. And second, the case of Nablus reflects the intrusion of the nineteenth-century reforms beginning in c. 1840 into provincial life. Thus, it reveals the nature of political power during the early nineteenth century, the manner in which the state then operated. At Nablus (and across the empire), the central state fused with the local notables in a new way, making their power a part of its own authority. Here and elsewhere, Istanbul legitimated local elites by making them part of the new, centrally created institutions at the local level, and vice versa. The central government was being legitimated on the local scene (as the Damascus example also illustrates) because of the co-operation of the local elites who joined in centrally organized institutions, giving these credibility in the eyes of the local population. Here, then, is the mutually beneficial arrangement between capital and province that lay at the heart of Ottoman rule.

The first part of our Nablus story begins at the moment when Napoleon Bonaparte, after invading Egypt, marched northward into Syria and attacked Acre in 1799. To defend his provinces, Sultan Selim III sent repeated decrees ordering local military forces to gather and attack the invader. In this atmosphere, a local official in Jenin, near Nablus, wrote a poem exhorting his fellow leaders in the region to resist Bonaparte. Enumerating each one of the ruling urban and rural households and families, he praised them for their courage and military strength. However, not once in this poem of twenty-four stanzas did he mention the sultan or Ottoman rule, “much less the need to protect the empire or the glory and honor of serving the sultan.”10 Instead, he referred to local elites, and to the threat to Islam and to women. As for the flood of imperial decrees into the area calling for action, he mentioned them only in passing, by saying that they came “from afar.” How remote seem the awesome towers and walls of Topkapi.

How much control did the state have in this region? Seemingly little. It had such trouble collecting taxes in the Palestine area that it used the tour system. This method had been initiated by the al-Azm appointee to the Damascus governorship in 1708. Thus, a few weeks before the Ramadan month of fasting, the governor annually led a contingent of troops to specified locations in the Nablus area, physically and personally appearing to remind the inhabitants of their fiscal obligations to the state. Even so, the taxes were rarely paid fully or in time.

Within Palestine at large, autonomy varied considerably. When Istanbul called for soldiers to fight Napoleon, the leader of districts near Jerusalem appeared before its court and promised that he would provide a certain number of troops or pay a fine. But in more distant Nablus, leaders dragged their feet. See the frustration of the faraway Sultan Selim III:

Previously we sent a … [decree]… asking for 2,000 men from the districts of Nablus and Jenin to join our victorious soldiers…ina Holy War. Then you signed a petition excusing yourselves, saying that it was impossible to send 2,000 men due to planting and plowing. You begged that we forgive you 1,000 men…and in our mercy we forgave you 1,000 men. But until now, not one of the remaining 1,000 has come forward… [Therefore] we will accept instead the sum of 110,000 piasters…If you show any hesitation…you will be severely punished.11

In the end, the central state received neither the troops nor the money. But, it is important to note, Nablus leaders were not challenging Ottoman rule and, indeed, they fought against the French. But they were not going to surrender their autonomy and sought to guard their own economic, social, and cultural identity and cohesion against interference from the capital. Clearly, as this example shows, Istanbul in 1800 was no powerful force in the everyday affairs of Nablus.

To better understand the impact of central policies on Nablus life beginning around 1840, the second part of the story, we need first to consider the host of measures promulgated to extend state control into the countryside across the empire. These included steps to increase its military presence, keep the population disarmed, revive conscription, and maintain the head tax. In the Anatolian (and some other) areas of the empire during the mid-1840s, survey teams enumerated the size and wealth of every household, including a staggering variety of livestock – sheep, goats, horses, cattle, as well as the income from agriculture, manufacturing and other activities. More broadly, the state launched efforts to count the population in the late 1840s (and, in 1858, codified the existing land legislation). By the end of Sultan Mahmut II’s reign in 1839, local notables generally no longer acted independently of the center. Indeed, Istanbul often appointed formerly autonomous dynasts to other corners of the empire, for example, sending the powerful Karaosmanoğlu of west Anatolia to be governors of Jerusalem and Drama. Thanks to such changes, the central state became a more important element in local politics almost everywhere in the empire.

But the social, economic, and political influence of most notables remained substantial if not intact (also see chapter 4). The same local families who had dominated regional politics and economics in the eighteenth century continued in power, remaining until the early twentieth century and sometimes later. Former notables and their descendants continued to serve as regional officials, frequently on the new local councils created by the state. Later on, when other administrative changes made these posts unpaid, the continued domination by local elites was guaranteed since none but the wealthy could afford to serve. Also, recall that tax farming prevailed until the end of the empire, thus continuing local notables’ sway in maintaining a crucial role in the local economy. They dominated the agrarian sector in other ways, for example, maintaining a choke hold on credit, both informal and formal, including the state-financed Agricultural Bank. Local and central elites thus both competed and co-operated in the extraction of taxes. In the later nineteenth century, cultivators’ taxes supported local elites as they previously had and, to a greater extent than in the past, the central state elites as well. Thus, the negotiated compromise between central and provincial elites likely increased the overall tax burden of the average cultivator.

In 1840, Istanbul inaugurated a series of changes in the formal provincial administrative organization in order to win over the local notables and rule the provinces with and through them. Imperial legislation established a council for each province (vilayet) and district (sancak). Each respectively consisted of thirteen members, seven representing the central government and six elected by and from among local notables. The sub-district (kaza) council would have five members, chosen from the local notables, including non-Muslims. Electors at the lowest, nahiye, level, were to be chosen by lot. Over each of the four levels, Istanbul appointed supervisory officials. In these provisions, Istanbul offered official recognition of local notables’ participation in the new central administrative structures while seeking to gain more control over them. Thus, the 1840 changes did not break with the past but rather tried to redefine the terms of notables’ involvement in governing.

In Nablus, the 1840 imperial edict concerning the councils touched off a prolonged round of intense negotiations over issues of central control and local autonomy, part of a long-standing tug of war between the center and the local elites. In this case, members of the local ruling group, who were the Nablus advisory council, negotiated with the central state as they had in the past. But there was a difference: the central state had become more aggressive and intrusive than before. The Jerusalem governor wrote to Nablus and asked the existing local council to nominate persons who would serve in the next council, asserting these must be drawn from both the Muslim and non-Muslim communities. The Nablus Muslim notables, who were running local affairs, asserted that the present membership of the council was the natural leadership of the area and so should continue without change. Moreover, they explicitly rejected the right of the state to help name the council and its leaders. Discussions dragged on for several months and ended in a negotiated compromise; the Nablus notables kept most of their autonomy but agreed to the inclusion of some new members. In this case of Nablus, council members did not seek to challenge the legitimacy of the new councils since it was a vehicle by which they, a (new) class of merchants and manufacturers in the town, had been given a formal voice in the political process. Thus, the centralizing state was able to insinuate itself more than before into local structures while local elites successfully warded off most of the effects of the centralization program.

These tense, sometimes combative, yet symbiotic and mutually beneficial relationships between the Istanbul regime and the local elites defined the new age of growing centralization. The trends displayed at Nablus in 1840 accelerated throughout the remainder of the Ottoman epoch, everywhere in the empire. Thus state control and interference in everyday life increased over the course of the century; the central bureaucracy grew by leaps and bounds and, in the age of Sultan Abdülhamit II truly was present in most corners of the empire. And yet, as a final example of Ottoman rule in Transjordan again reminds us, local groups successfully resisted these imperial encroachments. There, as a 1910 revolt clearly demonstrated, the writ of Istanbul remained limited. On the one hand, villagers and bedouin finally were compelled to pay taxes, at a level basically satisfactory to the capital. But, on the other hand, they successfully continued to refuse any form of registration and outright rejected military conscription as well as state efforts to take away their personal firearms.

Entries marked with a * designate recommended readings for new students of the subject.

*Abou-El-Haj, Rifaat. The 1703 rebellion and the structure of Ottoman politics (Istanbul, 1984).

*Alderson, A. D. The structure of the Ottoman dynasty (London, 1956).

Artan, Tülay. “Architecture as a theatre of life: profile of the eighteenth-century Bosphorus.” Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1989.

*Atıl, Esen. Levni and the surname. The story of an eighteenth century Ottoman festival (Istanbul, 1999).

Barbir, Karl K. Ottoman rule in Damascus, 1708–1758 (Princeton, 1980).

Barkey, Karen. Bandits and bureaucrats: The Ottoman route to centralization (Ithaca, 1994).

Bonner, Michael, Mine Ener, and Amy Singer, eds. Poverty and charity in Middle Eastern contexts (Albany, 2003).

*Doumani, Beshara. Rediscovering Palestine: Merchants and peasants in Jabal Nablus, 1700–1900 (Berkeley, 1995).

*Faroqhi, Suraiya. Pilgrims and sultans: The hajj under the Ottomans (London, 1994).

*Fattah, Hala. The politics of regional trade in Iraq, Arabia and the Gulf, 1745–1900 (Albany, 1997).

*Gavin, Carney E. S. et al. “Imperial self-portrait: the Ottoman Empire as revealed in the Sultan Abdul Hamid II’s photographic albums.” Published as a special issue of the Journal of Turkish Studies, 12 (1988).

*Hourani, Albert. “Ottoman reform and the politics of the notables,” in W. Polk and R. Chambers, eds., The beginnings of modernization in the Middle East: the nineteenth century (Chicago, 1968), 41–68.

*Khoury, Dina. State and provincial society in the Ottoman Empire: Mosul 1540–1834 (Cambridge, 1997).

*Özbek, Nadir. “Philanthropic activity, Ottoman patriotism and the Hamidian regime, 1876-1909.” International Journal of Middle East Studies, 37, 1 (2005), 59–81

*Peirce, Leslie. The Imperial harem: Women and sovereignty in the Ottoman Empire (Oxford, 1993).

Penzer, N. M. The harem (London, 1965 reprint of 1936 edition).

Rogan, Eugene L. Frontiers of the state in the late Ottoman Empire. Transjordan, 1850–1921 (Cambridge, 1999).

Zarinebaf-Shahr, Fariba. “Women, law, and imperial justice in Ottoman Istanbul in the late seventeenth century,” in Amira El Azhary Sonbol, ed., Women, the family and divorce laws in Islamic history (Syracuse, 1996), 81–95.

1A. D. Alderson, The structure of the Ottoman dynasty (London, 1956), 25.

2Tülay Artan, “Architecture as a theatre of life: profile of the eighteenth-century Bosphorus,” Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1989, 74.

3Alderson, Structure, 125.

4My thanks to Hakan Karateke for his observations on this point.

5Artan, “Architecture,” 75ff.

6Karl K. Barbir, Ottoman rule in Damascus, 1708–1758 (Princeton, 1980).

7Ibid., 19–20.

8Also see above, pp. 46–50.

9Beshara Doumani, Rediscovering Palestine: Merchants and peasants in Jabal Nablus, 1700–1900 (Berkeley, 1995).

10Ibid., 17.

11Ibid., 18.