17

Make ’Em Laugh, Make Her Laugh

You can’t laugh and be afraid at the same time.

—STEPHEN COLBERT

I am incapable of telling a joke. In fact, I know only one:

Old Mr. Cohen comes in the door and says, “Honey, I’m home.”

Old Mrs. Cohen says, “Herbie, come upstairs and fuck me.”

He says, “I can’t do both.”

Because of my straight face, which I inherited from my dad, people can’t tell if I’m kidding or not. I think he learned it from his Hungarian father, who reportedly never laughed, or joked, or indeed spoke to my father much at all. Harvey Fierstein once said to me, “You don’t even know if you’re kidding or not.” He had a point.

For me, being funny was a deliberate decision.

I had a Spanish teacher in high school who was tough and sarcastic, and one day I’d had it. She said something snarky, and I said, “Oh, teacher made a funny!” I had no idea that I was going to say that and I don’t think it was vintage Noël Coward material, but it got a laugh in the class. And the teacher’s face told everything—she had been disarmed. I saw her immediately recalibrate our relationship. Humor is a negotiating tool with bullies. This is a bit too simple, but light is shed in the laugh, whether it be George Bernard Shaw or Beppy struggling for just a little respect in a Spanish class at Lincoln High School in San Francisco.

One night in November 2016, my wife and I attended a Broadway performance of Oh, Hello. The previous Tuesday, our house had been decimated by the presidential election news and now a very gloomy twosome was sitting in traffic on the way to Manhattan’s Lyceum Theatre, listening to back-to-back depressing NPR news hours—transition teams in the Oval Office, rallies across the United States.

My wife, Kasia, said as we took our seats in the packed theater, “I’ve never needed to laugh as much as tonight.” And we were rewarded. The two stars, Nick Kroll and John Mulaney, hit the stage running and broke every comic boundary in the book. They were fearless, irreverent, and heroic, and the laughs were earned. But that night there was a difference—there was a heart and a warmth and a need underneath the laughs. There was hunger for the sanity and health that is implicit in comedy.

It made me think of a night in 1963—November 23, to be exact. It was a Saturday, the day after John F. Kennedy was assassinated. I told Mom and Dad I was going to the movies. They were still staring at the television set like the rest of the nation when I headed out to a movie house on Nineteenth Avenue, which was showing the Steve McQueen movie The Great Escape. I thought I would be sitting alone in a darkened theater, but it was packed, every seat taken. As the movie started, Mr. McQueen made a simple sarcastic retort to one of his fellow prisoners (it takes place in a German prison camp during World War II) and it got what we call a “house laugh”—it was earned but it was also needed.

It was the same at Oh, Hello. I heard Kasia tell one of the actors as she hugged him in congratulations, “Oh, we so needed to laugh tonight.”

Laughter is Darwinian, it is for survival, it is for health. There was a shaft of light in the Lyceum Theatre that night. Walking to our car on the chilly Manhattan streets after the show, we stopped at a halal stand to buy a lamb and chicken shawarma on pita with a fantastic yogurt sauce—twelve dollars, best meal in town. We were renewed with a sense of courage.

Humor has been an actual lifesaver for me. Growing up, I got pretty good at timing when my mother was about to go off and “zing” me with some less than complimentary comment. A favorite refrain of hers was “Look how you look.”

Then one day, it hit me: If I could make my Spanish teacher laugh, maybe I could make Mom laugh and distract her from the onslaught, or at least buy me some time to figure out how the fuck to proceed. Yes, my humor is totally fear-based. When my antennae pick up danger and the Klaxons are going off, I get funnier.

The night they pulled me out of my acting class to come quick, my mother was failing rapidly, we drove up to the valet stand at Century City Medical Center and I asked the parking attendant, “If my mother dies, do I get free parking?” My assistant almost fell out of the car with embarrassment. Fear-based.

To my mind, Donald O’Connor’s performance of “Make ’Em Laugh” in Singin’ in the Rain is hands down the great song and dance number in the history of film. He dances around making an artful fool of himself, mugging and goofing and throwing himself through a wall with great precision, all in the service of laughter. Back in the audiovisual room at San Francisco State, watching him do that number over and over again, I would lip-sync along with the lyrics. It was my dirty little secret in the hip avant-garde theater department where we talked only of Ionesco, Artaud, and Camus. But the truth for me was the line “My dad said, ‘Be an actor, my son, but be a comical one.’ ” Mr. O’Connor also breaks every rule in the comedy book.

One of the two (gulp) times I guest-starred on The Love Boat—$5,000 and all the ignominy you can handle—I walked into a room on the set and there was an older woman who looked familiar. I wasn’t sure if it was who I thought it was. I decided to ask the assistant director.

“Excuse me,” I said, tapping him on the shoulder.

“Yes, Mr. Tabor?” (A common occurrence in those days.)

“Who is that woman sitting over there?”

He looked down at his clipboard. “Gish…Lillian.”

D. W. Griffith invented the close-up for her and her sister “Gish, Dorothy” in Orphans of the Storm. I thought, It’s bad enough I’m here. Why in God’s name is she here?

She was sitting ramrod straight and looking at the lights being set and focused for her scene. If anyone knew light, it would be Lillian Gish. I asked her manager if I could talk to her.

“Oh thank you, would you? No one here knows who she is.”

I sat in the director’s chair next to hers, and I told her, “Thank you,” and that we all stand on her shoulders. She smiled while continuing to stare straight ahead. Beppy Tabor knows how to pay a compliment.

On another part of the set, I saw my hero, Donald O’Connor, sitting next to a seal. Sylvia the Seal, or, to make that morning all of a piece—“Seal, Sylvia.” She got billing ahead of me in the credits for the show, and she stank to high heaven. I thanked Mr. O’Connor for “Make ’Em Laugh” and confessed my San Francisco State vigils and how important that song was to me. “That song is why I’m standing here today.” He said nothing. Also mute was Sylvia.

I’ve always thought comedy was serious business. If you go backstage at a comedy, you are likely to encounter silence. If you ask me, Aristophanes should have taken higher billing in the Greek theater than Aeschylus—very few of us fuck our mothers (Oedipus), while governments have young and old marching to war at a moment’s notice (Lysistrata).

Anton Chekhov called his plays comedies because he was focused on man’s folly. “To Moscow, to Moscow” in his Three Sisters was a symbol of our fallibility, the human ability to reach for the stars and end up staying home to watch the Food Channel. Jill Soloway’s Transparent is a comedy in the same vein, because the Pfeffermans are simply and wonderfully human and ridiculous in their respective quests for freedom and authenticity.

I used to go with Jeff Altman to the Laugh Factory in Los Angeles to watch him do stand-up. I wanted to make a documentary that showed the journey from writing a joke to trying it out to standing it up. We waited at the bar while one comic after another tried out their material. The waiting performers were not happy or smiley. They looked as if this were an operating theater and complicated surgery was being done.

The most formative lesson I learned about humor was given to me by Barney Tambor, which is ironic considering my dad never went toward humor. He seldom smiled. As a Hungarian Jew, it just wasn’t part of his deal. I noticed this trait when I visited Hungary. These are not a tap-dancing people. They still have bullet holes in the walls from World War II, which ended more than seventy years ago. But those holes say, “You see what can happen?”

So when the doctor came to his hospital room at the John Muir Medical Center in Walnut Creek, California, and told him it was time to go home, there was nothing more they could do for him, my dad looked at me and shrugged. “Nu?” (So?) I helped him dress and get packed up, including the marijuana to help with the side effects of the chemo. I rolled him in his wheelchair past the nurses’ station. (His favorite nurse raised her hand and said, “Bye, Barney.” A lesson in economy that broke one’s heart to pieces.)

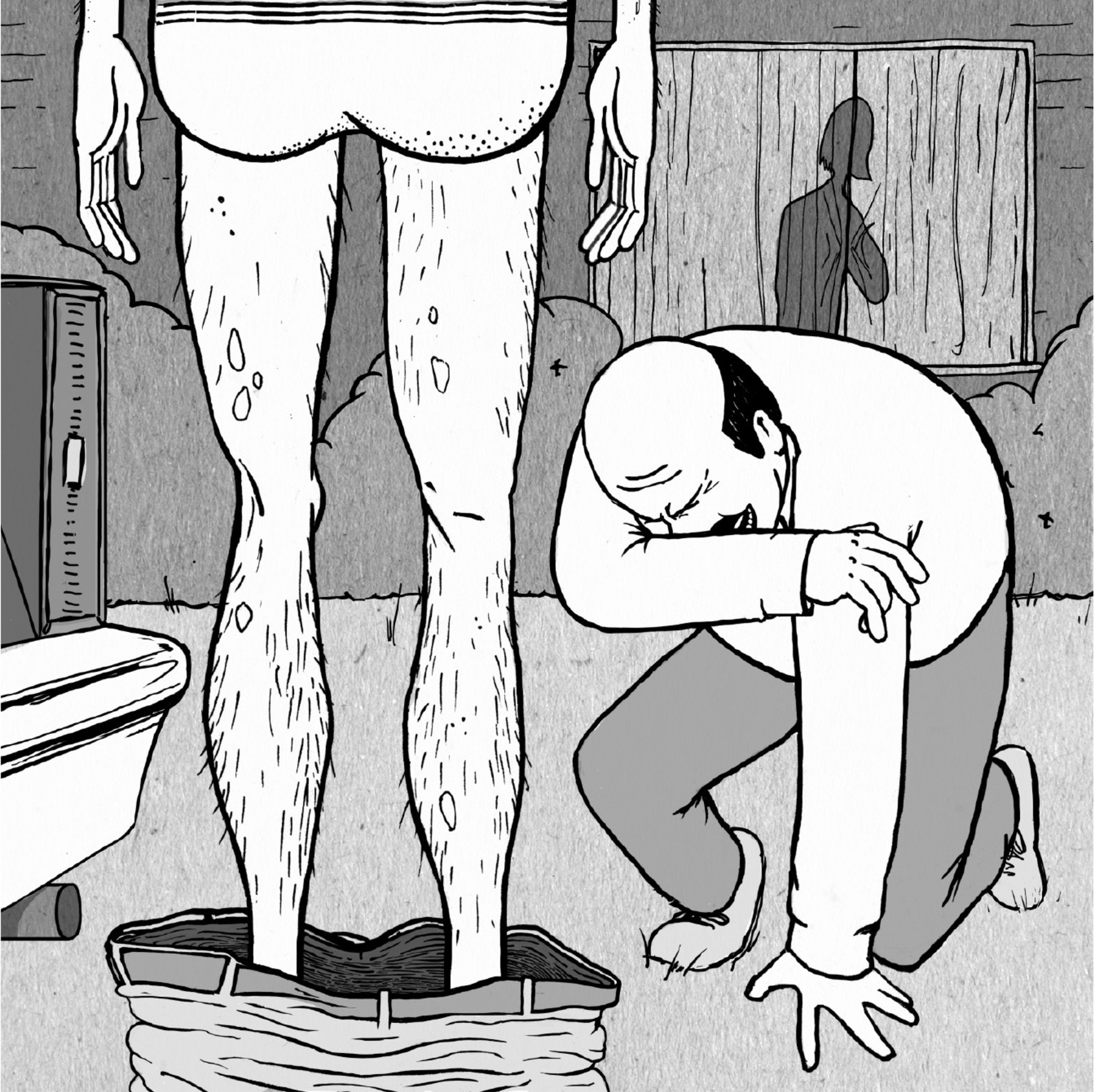

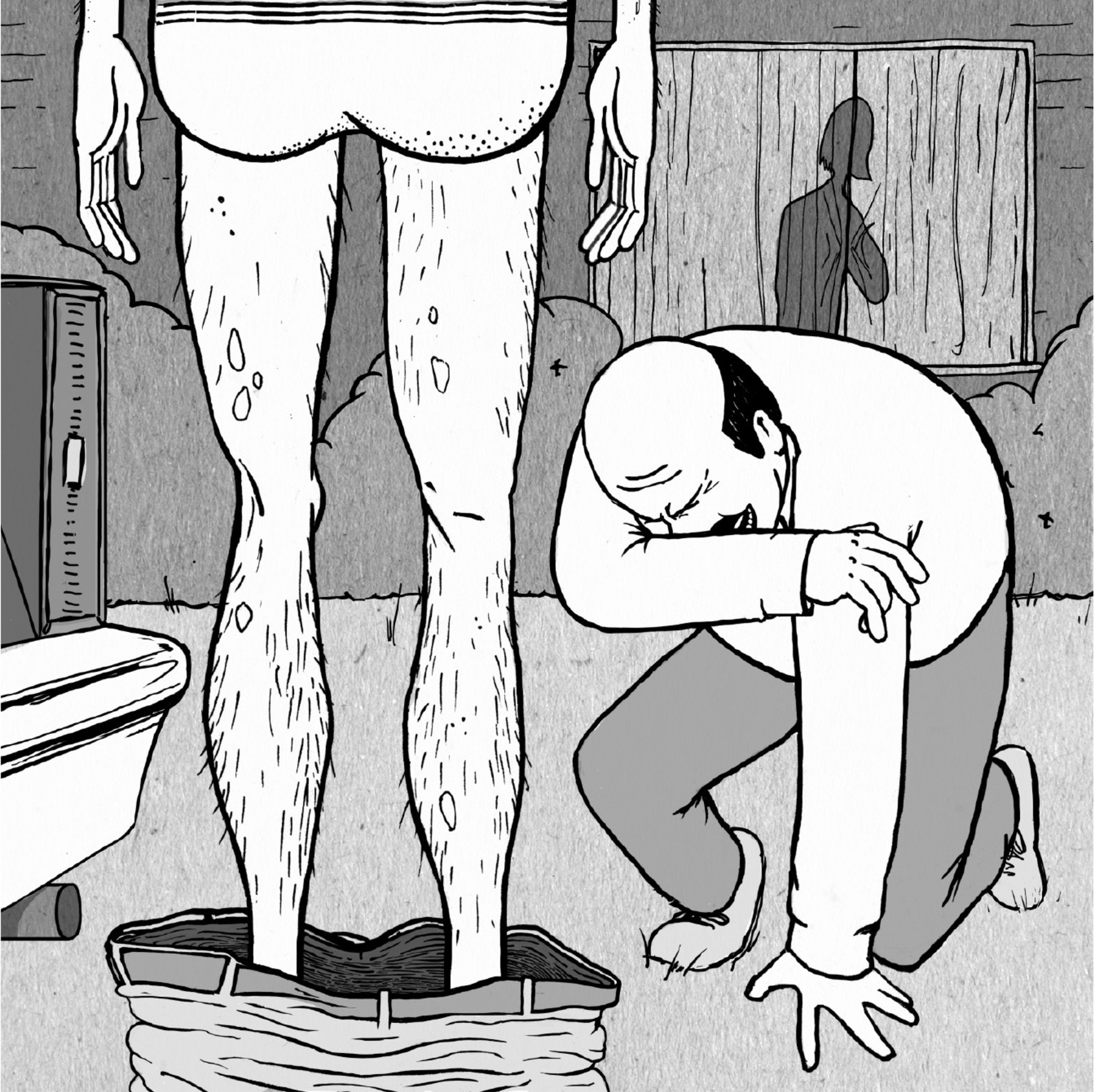

As we pulled into the driveway of their house, I saw my mother peering through the front curtains. She’d hardly ever visited him during his many stays in the hospital after his diagnosis, her fear of death was so great then. I parked and got out of the car. I walked around to the passenger side to help my father. He had lost so much weight in the hospital, as he stood up his pants fell to his ankles. I saw the drapes close.

And my father and I started to laugh…and laugh and laugh, harder and harder, banging on the roof of the car with our hands. Tears were streaming down our cheeks, tears of grief and hilarity all at once. Our inability to deal with the horrendous loss that was bearing down on us played out in belly laughs that could be heard up and down the street.

Not many days later, after the doctor’s final visit to my father’s bedside at home and that final shot of morphine, he was gone. At the funeral, a Reform rabbi in a rainbow yarmulke (thank God my dad was dead, because that would have killed him) who had never met my father starting singing a song on his guitar like one of the Kingston Trio; it went, “Barney, oh Barney,” and my mother and I started to laugh. From behind, our shoulders heaving up and down, I’m sure people thought we were crying. It got so bad, I had to walk out of the synagogue and collapse outside in the Walnut Creek sun.

If there is a God, She lives within the sound of laughter. I search for humor like one of those old men with a metal detector on the beach looking for pennies. Laughter is the reason I’m living.