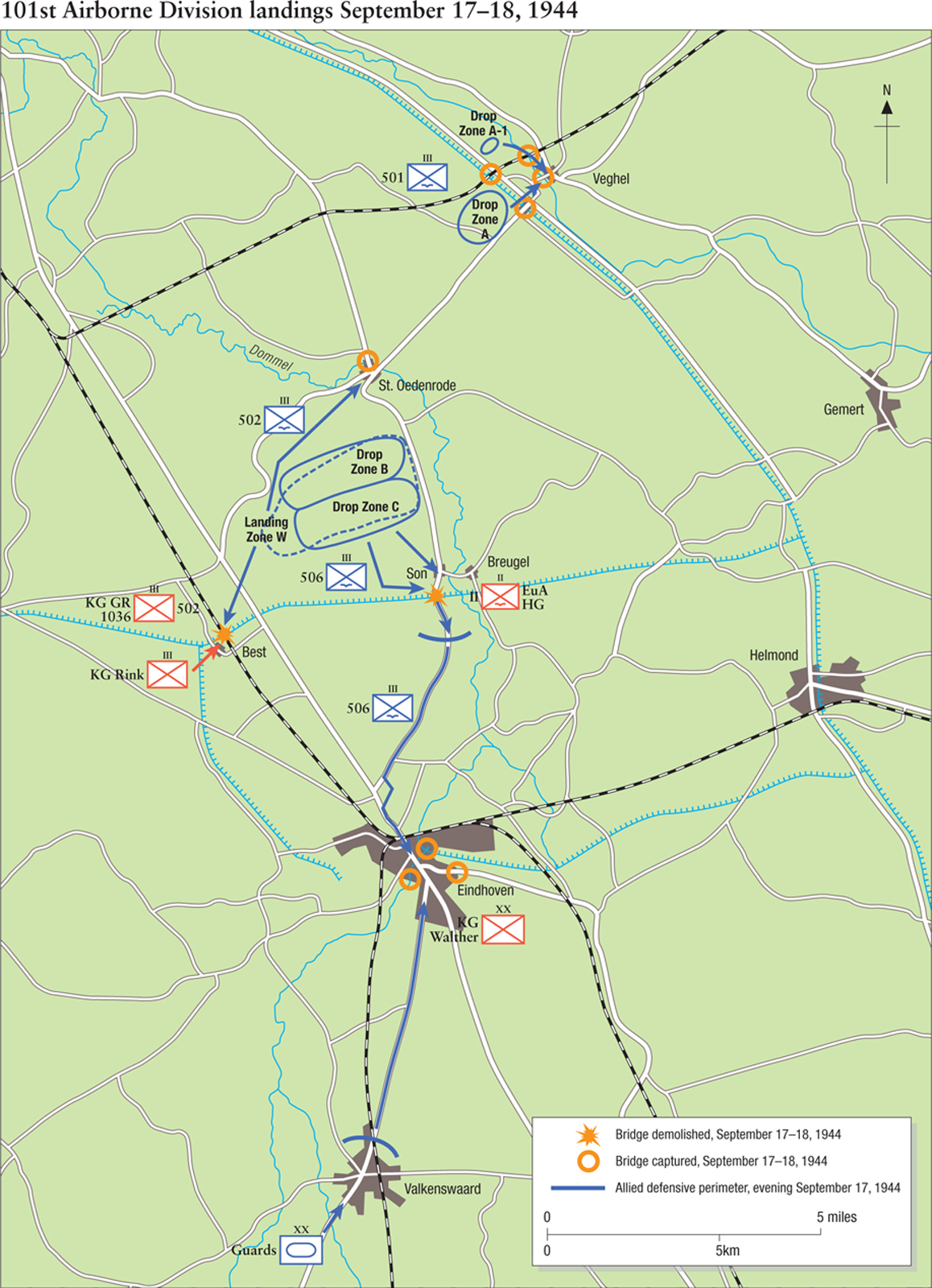

The initial 101st Airborne Division force was carried to the Netherlands in 436 C-47 transports and 70 gliders, and began around 1300hrs on September 17. In order to ensure accurate drops, four special Pathfinder detachments landed 15 minutes in advance of the main force. Due to the dispersion of the objectives, Maj. Gen. Taylor felt that it would be more prudent to land the division together in a central area, and then proceed to the objectives rather than to employ dispersed landing sites. Jump casualties were less than 2 percent of the 6,809-man force and most battalions were able to assemble within an hour of landing. In comparison to the Normandy night drops, it was a textbook example of navigation and planning.

The 502nd PIR landed on Drop Zone B without enemy opposition. The 1/502nd PIR set out for St. Oedenrode and seized the bridge over the Dommel River after a short skirmish. Co. H of 3/502nd PIR was assigned the highway bridge at Best and secured the bridge without initial resistance. However, in the early evening the bridge site was attacked by Kampfgruppe Rink, an improvised formation including the remnants of Maj. von Zedlitz’s GR 723, 719. Infanterie-Division, bits of the 245. Infanterie-Division and the Tilburg military police battalion. The remainder of 3/502nd PIR was ordered to reinforce Co. H and to take back the bridge the next morning. The divisional command echelon landed with the 502nd PIR and set up a command post in Son. The initial glider force followed an hour behind the parachute landings.

Dutch farmers Driek Eykemans and Toon Vervoort give a lift to glider infantry of the 327th GIR in the Son woods on September 18. The corporal talking to the farmers is Jaap Boethe, one of five Dutch commandos of No. 2 (Dutch) Troop of the 10 (Inter-Allied) Commando who were attached to the 101st Airborne Division. (NARA)

The 506th PIR landed at Drop Zone C without opposition and elements of the 1/506th PIR immediately set out for the three bridges over the Wilhelmina Canal near Son without formal assembly. As it transpired, German engineers had already blown two of the bridges up. The third bridge was held by II./Fallschirm-Panzer-Ersatz-und-Ausbildungs-Regiment “Hermann Göring,” which kept control of it long enough to finish its demolition before the arrival of the American paratroopers. The 506th PIR began crossing the canal by expedient means and created a bridgehead south of the canal, about 4 miles north of Eindhoven.

The 101st Airborne Division was reinforced on the afternoon of September 18 by their glider regiment, the 327th GIR. Here, a column from the 327th GIR including a jeep from the HQ & Service Company move down the Eindhoven–Nijmegen road at the eastern end of the landing zone and are greeted by local Dutch citizens. (NARA)

The 501st PIR landings on either side of Veghel were not entirely accurate, but the main objectives of the four bridges over the Aa River and the Willems Vaart Canal were quickly seized. Accompanying engineer troops assembled a second bridge over the Willems Vaart Canal. Resistance in the area was sporadic and light.

A Waco CG-4A, Chalk 52-A, disgorges its jeep in Landing Zone W on September 18 while curious Dutch civilians watch the proceedings. (NARA)

A patrol from the Headquarters Company, 506th PIR, receives the help of local Dutch teenagers during movements on September 18. The paratroopers found the local Dutch populace to be extremely helpful during Operation Market. (NARA)

On September 18, Operation Market was supported by the Eighth Air Force’s Mission 639 with heavy bombers dropping supplies from at low altitude. Of the 248 bombers participating, seven were lost over the targets to Flak, six damaged beyond repair, and 154 suffering damage. This B-24H of the 466th Bombardment Group, 96th Wing, 2nd Bomb Division is seen dropping supplies. (Patton Museum)

The paratroopers had landed in the rear area of the German defenses, where they were light or non-existent. This was not the case along the forward edge of the battle area, where the British Second Army began its advance on Eindhoven. Horrocks’ XXX Corps had spent the previous four days in penetrating the German defenses along the Albert Canal near Beeringen to reach to the Meuse–Escaut Canal closer to the Dutch border. The main opposition had been Von der Heydte’s Fallschimjäger-Regiment 6 and other elements of the improvised Division Walther. British artillery began a preliminary bombardment at 1400hrs and lead elements of the Irish Guards Group began the attack at 1435hrs.

The Eindhoven road was such an obvious objective that Division Walther had reinforced the defenses there with their usual hodgepodge of units. The eastern side of the road was manned by two understrength battalions of Kampfgruppe Heinke (III./SS-Pz.Gren.Rgt. 19 and II./Pz.Gren.Rgt. 21); the west side was covered by Von der Heydte’s FJR 6; blocking the road was the newly rebuilt FJR 18.

In the wake of the rolling artillery barrage, the Irish Guards’ Sherman tanks advanced quickly through the German infantry defenses. About ten minutes after the advance began, the lead tanks ran into Lt. Finke’s 14./FJR 18, an anti-tank platoon of about 30 troops equipped with Panzerfaust antitank rockets and supported by several war-booty Soviet 76mm divisional guns used in an anti-tank role. Nine Shermans were knocked out in quick succession. Typhoon fighter-bombers were called in to soften the opposition. The advance resumed at 1630hrs, and the town of Valkenwaard was reached around 1930hrs, a distance of about 7 miles from the start line. Rather than press on to Eindhoven 6 miles further, XXX Corps remained in the town for the night. The decision to halt the armored advance short of Eindhoven has remained controversial, especially since the Guards column contained the bridging equipment needed to rebuild an essential canal crossing at Son.

Columns from the Guards Armoured Division pour through Valkenswaard on September 18, 1944, while moving on towards Eindhoven. (NARA)

The 101st Airborne Division captured Eindhoven the following day. The 506th PIR set out for the city at first light. The 3/506th PIR skirmished with Division Walther near Woensel on the north side of the city so 2/506th PIR moved to the east. First contact with British reconnaissance patrols was made around 1215hrs, and by 1300hrs the 2/506th PIR began securing the town. The paratroopers made the link-up with the main body of the Irish Guards around 1800hrs on the south side of Eindhoven. The original expectations were that XXX Corps would have reached Veghel by this time. British engineers began bridging the Son Canal around 2100hrs and it was ready for vehicle traffic at 0615hrs on September 19, D+2. The timetable to reach Arnhem was already slipping badly.

On the morning of September 19, a Sherman V tank of the 2nd Grenadier Guards crosses the new bridge over the Wilhemina Canal at Son erected by the 14th Field Squadron RE to replace the bridge demolished by the Germans the day before. (NARA)

Around 1000hrs on September 19, the Grenadier Guards linked up with the 82nd Airborne Division at Grave to a warm welcome from the local Dutch citizens. (NARA)

The counterattack by the 59. Infanterie-Division near Best on September 19 was broken up and a large number of prisoners captured. Here, a patrol from the 502nd PIR escorts prisoners to the rear. (NARA)

In contrast to other sectors of the 101st Division, the 502nd PIR continued to experience a far heavier level of German resistance in their attempts to re-capture the bridge at Best. On September 18, the understrength 59. Infanterie-Division arrived by train in the Tilburg area. In the afternoon, two weak battalions from GR 1036 were sent to reinforce Kampfgruppe Rink near the Best Bridge. German troops demolished the bridge at 1100hrs on September 18. Unaware of this, the 101st Airborne Division headquarters continued to commit forces to this mission, including 2/502nd PIR. The fighting around Best was the most intense in the 101st Airborne Division sector.

With the bridge at Son open, XXX Corps began a rapid exploitation out of Eindhoven on September 19. Lead elements of the Guards Armoured Division reached St Oedenrode and Veghel by 0645hrs, heading for a link-up with the 82nd Airborne Division later in the morning.

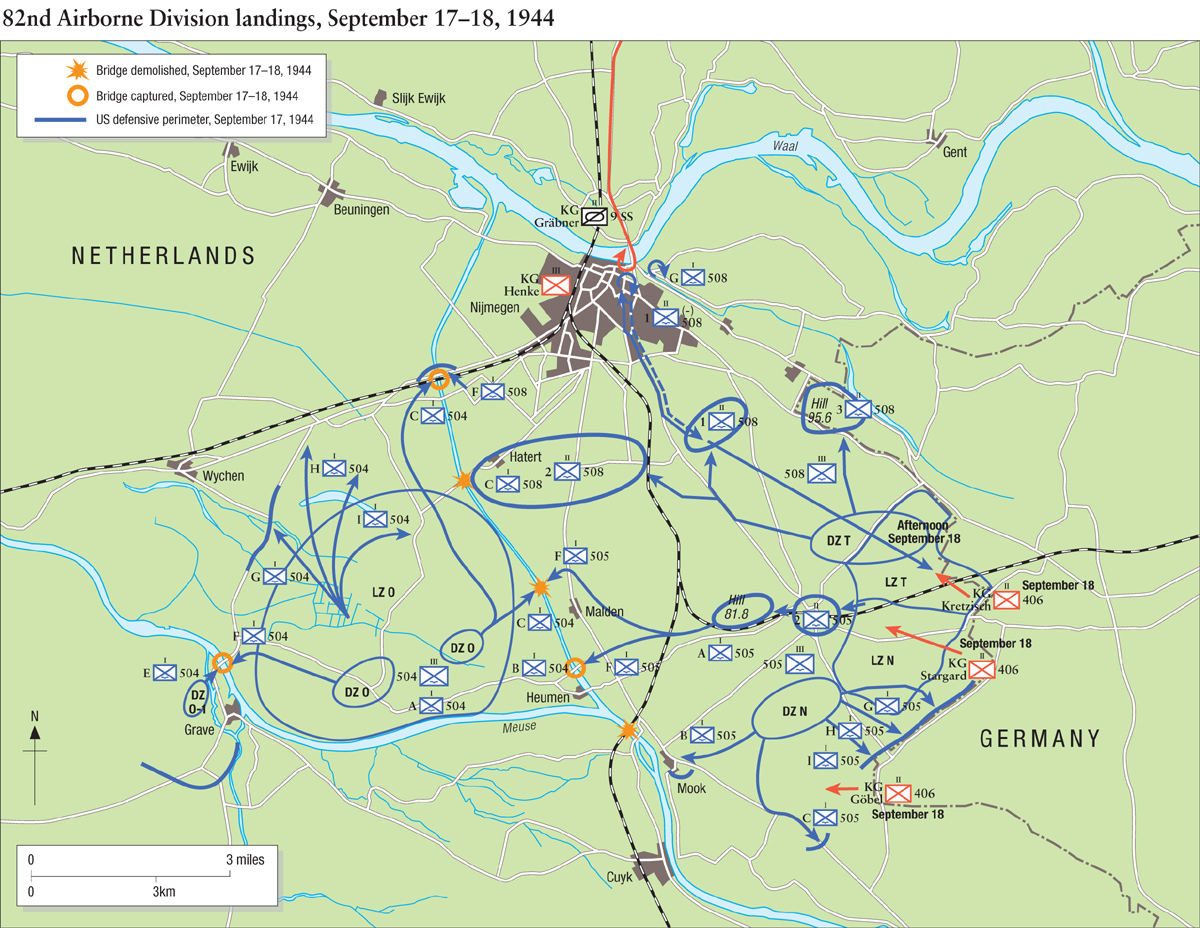

The 82nd Airborne Division was carried into action by 482 C-47 transports and 50 gliders, including 7,277 paratroopers and 209 glider infantry. The main mission was preceded by a pair of C-47s carrying Pathfinder teams which landed at Drop Zone O at 1247hrs. Ten paratrooper transports were lost during the mission; one glider transport was lost.

Most of the 504th PIR landed in Drop Zone O near Overasselt, and fanned out in multiple directions to seize crossings over the Maas–Waal Canal and to take the eastern side of the Grave Bridge (Bridge 11) from the Heuman side. Company E, 2/504th PIR, landed in Drop Zone O-1 immediately to the west of the Grave Bridge while the rest of 2/504th PIR landed in Drop Zone O and marched to the bridge. The bridge had been prepared for demolition on September 7, but on September 17 before the airborne landings, one of the main fuzes was found to be inoperative. The commander of the demolition detail and another soldier went to Nijmegen to get a replacement. During the American attack, only a single soldier from the demolition party was present at the bridge, and unable or unwilling to activate the demolition charges himself. Even though the bridge was protected on both sides by pre-war Dutch bunkers, the German troops guarding the bridge were quickly overcome.

A platoon leader of the 82nd Airborne Division gives final instructions to his squad leaders prior to boarding their aircraft at Cottesmore on the morning of September 17, 1944. (NARA)

A view inside “Chalk 1,” the C-47 Skytrain carrying Gavin and the headquarters staff of the 82nd Airborne Division. In the foreground to the left is Col. John Norton, the divisional G-3 (operations), and next to him, Capt. Hugo Olson, Gavin’s aide. (NARA)

The 504th PIR was also tasked with capturing the west side of four other bridges along the Maas–Waal Canal in conjunction with other units of the division from the eastern side. The southernmost bridge (Bridge 7) was captured, the ones north of Malden (Bridge 8) and Hatert (Bridge 9) were blown by the Germans and the damaged bridge at Honinghuyje (Bridge 10) was seized the following day.

A view out the port window of a C-47 on the way to the Netherlands on September 17 with Serial A-9 from the 36th Troop Carrier Squadron, 316th Troop Carrier Group, that was carrying Co. B, 504th PIR, heading for Drop Zone O. (NARA)

The 505th PIR landed further east around Groesbeek in two drop zones, established a defensive perimeter towards the Reichswald to the southeast and linked up with the 504th PIR along the Maas–Waal Canal. The rail bridge on the northwest side of Mook had already been demolished by the Germans.

The 508th PIR landed northeast of Groesbeek in Drop Zone T and its principal mission was to seize and control the Groesbeek Heights west of Berg-en-Dal, including Hill 95.6, which dominated the flat Dutch landscape in the area. Once the area was secure, Browning’s I Airborne Corps headquarters landed, consisting of 105 troops in 32 Horsa and six CG-4A gliders; 28 arrived safely.

A dramatic view taken by a Signal Corps motion picture cameraman during the drop by the 505th PIR over Drop Zone N south of Groesbeek. (NARA)

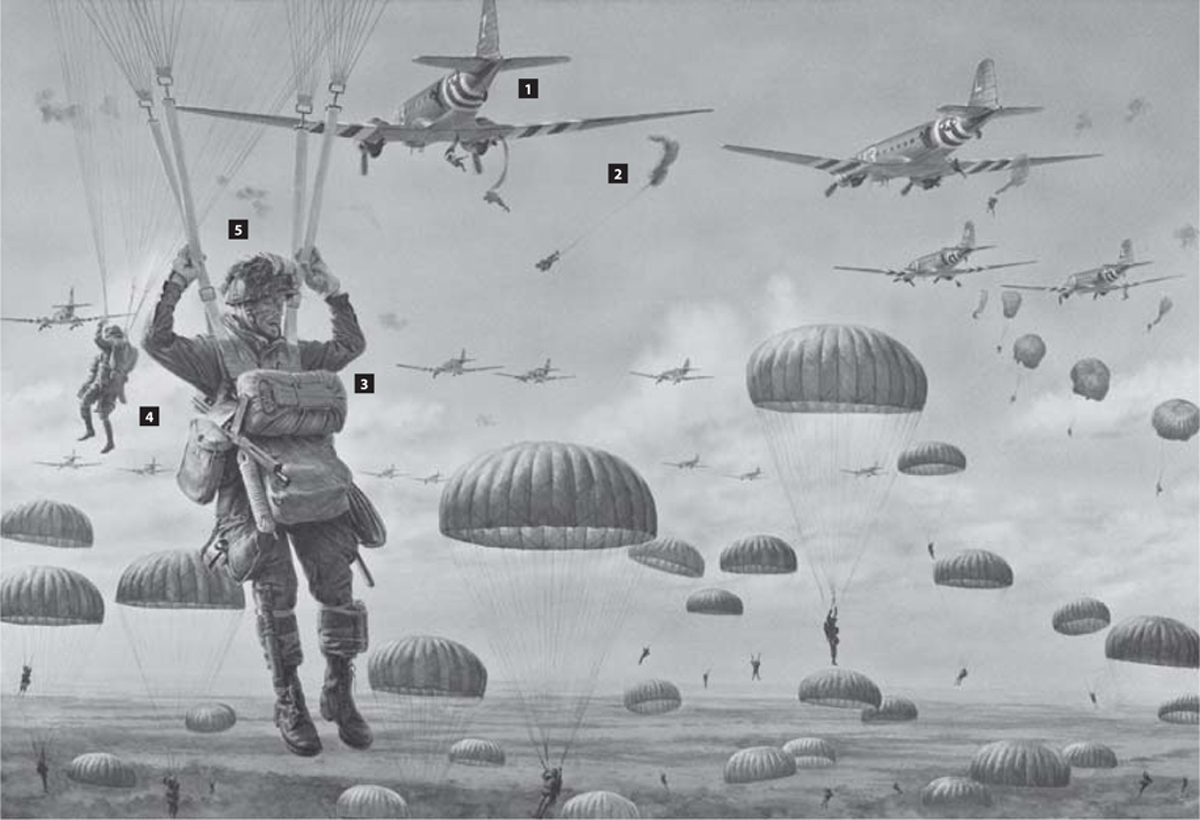

Serial 17, consisting of 45 C-47 Skytrains (1) of the 99th and 100th Troop Carrier Squadrons, 441st Troop Carrier Group, departed for the Netherlands from Army Air Force Station No. 490 (RAF Langar), arriving over Drop Zone T at 1328hrs. The first two “Chalks” consisted of pathfinders from the 325th GIR. The following aircraft consisted of troops from the 1/508th PIR and the regimental HQ of the 508th PIR. Of the 45 transport aircraft, three were lost to Flak. The rest of the 441st Troop Carrier Group consisting of the 301st and 302nd TCS made up serial A-19, which dropped the 2/508th and elements of the regimental HQ company starting around 1334 hours; this serial lost two aircraft to Flak. The various squadrons could be distinguished by the alpha/numeric code painted on the nose: 99th TCS (3J); 100th TCS (8C); 301st TCS (Z4) and 302nd TCS (2L).

The usual load for a combat jump was 15 men per aircraft, with the senior officer usually jumping first. As the static line opened up the T-5 parachute pack, the olive drab canopy began to deploy (2). The large surface of area of the deploying canopy tended to swing the paratrooper around again, and within seconds, the shroud lines cleared the pack and the canopy blossomed, giving the paratrooper a hard jolt. US paratroopers also carried a reserve chute on their chest (3). The standard weapon for paratroopers was the normal M1 “Garand” rifle, though of course other weapons were carried depending on the table of equipment such as the .45 cal. Thompson sub-machine gun (4). The paratroops carried a good deal of equipment into combat. Under the parachute harness was a yellow “Mae West” life vest, a musette bag was hung under the reserve chute, an ammunition bag and an assault gas mask in waterproof bag off the hips. Fighting knifes were often strapped to above the jump boots, and a .45 cal automatic in a holster on the hip with a folding knife in its scabbard in front of this. The paratrooper’s M1C helmet resembles the normal GI helmet, but has a modified liner and chin-strap to absorb the shock of parachute operations. A first aid packet is taped to the front of the helmet for ready access (5). Many paratroopers wore gloves to protect their hands during the jump.

The critical objective in the initial landings by the 82nd Airborne Division was the multi-span bridge over the Maas River near Grave. This bridge survived the war today and this view was taken from the western side near the “Special Drop Zone” where the Co. E, 2/504th PIR, landed. (Author)

IX Troop Carrier Command missions for Operation Market, September 17–23, 1944

| Sept. 17 | Sept. 18 | Sept. 19 | |

| Aircraft (parachute) | 910 | 126 | 60 |

| Aircraft (gliders) | 120 | 904 | 385 |

| Aircraft lost | 34 | 20 | 19 |

| Aircraft damaged | 279 | 241 | 185 |

| Gliders dispatched | 120 | 904 | 385 |

| Gliders landed | 110 | 853 | 225 |

| Paratroops carried | 14,009 | 2,119 | |

| Paratroops landed | 13,941 | 2,110 | |

| Glider infantry carried | 527 | 4,397 | 2,310 |

| Glider infantry landed | 506 | 4,255 | 1,363 |

| Troops landed total | 14,447 | 6,365 | 1,363 |

| Cargo carried (tons; para+glider) | 414+87 | 51+455 | 71+245 |

The airborne landings caught Model by complete surprise at his headquarters near the British landing zone in Oosterbeek. Once it had become clear that the British paratroopers had failed to secure the Arnhem Bridge, Model declared the Schwerpunkt (focal point) to be the southern sector from Nijmegen to Eindhoven. The 9. SS-Panzer-Division was tasked with pushing the British force away from the north end of the Arnhem Bridge; once this was accomplished the remaining British force around Oosterbeck would be eliminated by 9. SS-Panzer-Division supported by Tettau’s improvised division from the WBN. The 10. SS-Panzer-Division was instructed to ferry across the Waal, and take control of the key bridges at Nijmegen.

Although Student had been one of the pioneers of airborne operations, the Operation Market-Garden landings on Sunday afternoon came as a complete surprise to him. Student’s headquarters had been overwhelmed trying to deal with the threat of British ground operations from their bridgehead over the Meuse–Escaut Canal. About two hours after the landings, Student was delighted to receive a set of Allied operations orders that had been recovered from a glider that had landed near Vucht. These were quickly translated and a set immediately dispatched to Model’s temporary headquarters. This greatly aided in planning counterattacks.

Model instructed Student’s Fsch-AOK 1 to deal with the XXX Corps advance out of the Neerpelt bridgehead and the 101st Airborne landings. Kampfgruppe Chill was assigned to seal off the British penetration at Valkenswaard. Model ordered AOK 15 to route the 59. Infanterie-Division from the Tilburg area to act as the main counterattack force against the 101st Airborne Division. As mentioned previously, one of its regiments arrived on the afternoon of Monday, September 18, and took part in the violent struggle around the Best Bridge. Efforts by AOK 15 to interdict the Allied advance from the western side were constrained by Hitler’s admonition to hold the Scheldt Estuary at all costs.

Panzer-Brigade 107 was in transit to the Aachen area at the time, but was routed instead to Student’s sector. It did not reach the area in strength until Tuesday, September 19. Early on September 18, Model transferred the 86. AK (LXXXVI Korps) headquarters under Gen. der Inf. Hans von Obstfelder to Student’s command to direct Division Erdman and Division Nr. 176.

The 5. Fallschirmjager-Division was decimated in the fighting at St Malo in the summer and survivors, mainly from rear support elements, were consolidated into Kampfgruppe Hermann and thrown into combat against the 82nd Airborne Division around Mook on September 19. (NARA)

Since Student’s forces were so heavily concentrated along the forward-edge of battle on the Dutch border, Model instructed Wehrkreis VI to take over the battle against the 82nd Airborne Division around Groesbeek using Korps Feldt. Its Division z.b.V.406 was ordered to seize control of Groesbeek Heights.

The Luftwaffe instructed IX Fliegerkorps to provide air support to army units to defeat the Allied airborne landings. The first attack on the night of September 18 was directed against the British bridges over the Meuse–Escaut Canal at Neerpelt. Due to the chaotic conditions at the bases in neighboring Germany, only about a dozen Do-217 bombers of I./KG 2 departed from Münster-Handorf, of which several failed to find the target. The bombing results were negligible. Berlin insisted on a major assault against Eindhoven but fuel shortages limited the attack force to 78 bombers. The attacks began around 1930hrs on the night of September 19, killed about 190 civilians, but had little impact on the British advance.

One of the most controversial aspects of the 508th PIR’s missions was the issue of the Nijmegen bridges. Prior to the mission, Gavin had authorized the regiment’s commander, Col. Roy Lindquist, to commit a battalion to a rapid seizure of the highway bridge at Nijmegen via the open terrain along the Waal River once it was clear that the Groesbeek Heights were secure. In the afternoon, members of the Dutch resistance met elements of the 1/508th PIR who were moving to the west of Drop Zone T to establish their defensive perimeter. They informed the Americans that the city was very lightly held and that the bridge was theirs for the taking. Disregarding Gavin’s instructions to advance on the bridge via the open river edge, Lindquist instructed the battalion commander, Lt. Col. Shields Warren, to dispatch two companies to the headquarters of the Dutch resistance in Nijmegen through the congested town. This was in part due to the mistaken Dutch view that the demolition controls for the bridge were located in the city post office.

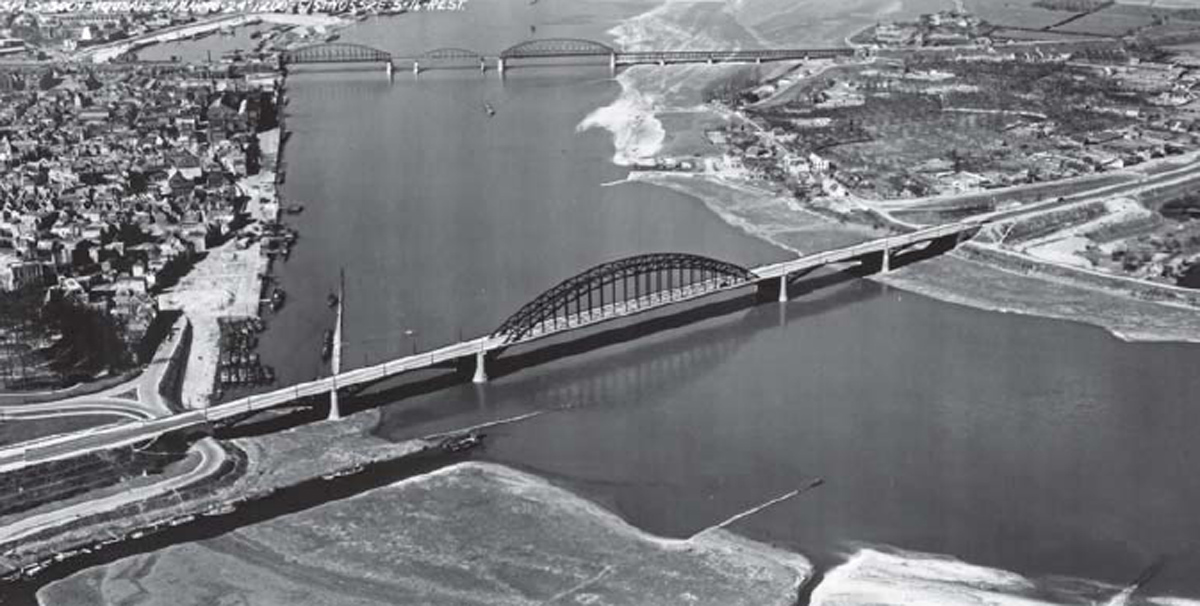

This post-war aerial photograph shows the city of Nijmegen from the south looking towards the suburb of Lent on the northern bank of the Waal River. The highway bridge can be seen in the upper right and the railroad bridge in the upper left. (MHI)

On September 17, the German defense of Nijmegen was chaotic, though much stronger than the Dutch resistance appreciated. On September 15, Student’s headquarters had dispatched the staff of its Erdkampfschule d.Lw. (Luftwaffe Ground Combat School) under Oberst Günther Hartung to take charge of the various training, reserve, and security units in the city. The core of the defense was Kampfgruppe Henke, led by Oberst Fritz Henke, commander of Fallschirmjager-Lehr-Regiment 1. This battlegroup of about 750 troops was based around elements of the Fsch.Pz.Ers.-u.Ausb.Rgt. HG including its Unteroffiziers-Lehr Kp 29 along with replacement troops from Ersatz-Bataillon 6 from Wehrkreis VI. The city had a variety of police and security units that were gradually incorporated into the defenses. In the days before the landing, they were reinforced with about 300 walking-wounded from the convalescent hospital in town. The 4./Flak-Abt. 572 stationed around the city had four 88mm Flak guns and eight 20mm automatic cannon. On September 17, Hauptsturmführer Viktor Gräbner led a motorized detachment from SS-Aufklarungs-Abt. 9 to the city to determine the state of its defenses. After finding the defenses in order, the detachment returned to Arnhem later in the day, only to be ambushed on the Arnhem Bridge by Maj. John Frost’s 2nd Parachute Battalion.

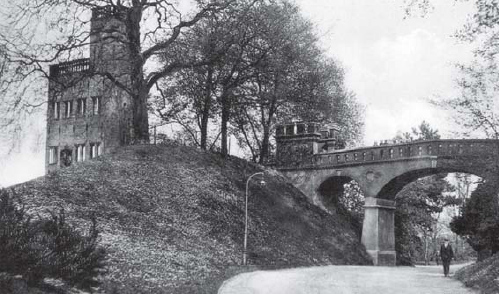

Lieutenant-Colonel Warren and the Co. A of 1/508th PIR did not set out for Nijmegen until 2100hrs while waiting for Co. B to arrive. By the time they arrived in the city, it was already dark and there was scattered skirmishing with German patrols. One patrol reached the Belvedere Tower at the southern end of the highway bridge. There were confused skirmishes with KG Henke in the dark. By dawn on September 18, the two paratrooper companies in Nijmegen requested the dispatch of the battalion’s remaining company to reinforce a planned attack on the bridge. In the meantime, Gavin had arrived at the 1/508th PIR headquarters to inquire about progress. When it was evident that the bridge was not yet in American hands, Gavin ordered Warren to withdraw his two companies back to the Groesbeek Heights due to the Korps Feldt attack on the perimeter that morning. The division’s frontage of over 25,000 yards was far in excess of what could be adequately defended and the battalion was badly needed on the Groesbeek Heights. Gavin was unwilling to leave an inadequate force at the bridge that would be hard pressed to defend itself, never mind secure both sides of the bridge. The two companies withdrew around 1100hrs.

In the meantime, Co. G, 3/508th PIR, had also sent out patrols towards the bridge along the river’s edge and around 0745hrs on the morning of September 18, the battalion commander instructed the company to capture the bridge. Company G reached to within small arms range of the bridge and began sniping at German positions, including the use of 60mm light mortars. The German defenses were too substantial to be overcome by a single company, and Co. G was forced back. It was eventually ordered to return to Berg-en-Dal in the afternoon, so ending the first half-hearted attempts to seize the bridge.

One of the mysteries of Market-Garden was why the Germans did not blow-up the bridges to prevent their capture by the Allies. The Nijmegen highway bridge had been configured for demolition almost from the time of its construction, with the Dutch army having an electrical detonation circuit built into the bridge, and connected to neighboring bunker on the north side of the bridge. During the German occupation after 1940, the preparation for bridge demolition was undertaken by the Sonderkommando der Pionertruppen (Special Engineer Command) based in Utrecht. The German system was designed to drop the bridge using about 1,000kg of high explosive located in a chamber inside the second stone pier from the north end. A supplementary Abdämmung (blocking) charge could be placed on the road surface to create a temporary breach in the bridge as an alternative to dropping the whole span or to supplement the main charge.

This blocking charge was left in the bunker on the northern Lent side of the bridge until needed, under the control of the city’s Ortskommandant. It was supposed to be placed on the roadway by a Schutzgruppe civilian militia directed by a team from the Utrecht Pionertruppe. On August 25, 1944, Himmler instructed SS police chief Rauter that he would be held personally responsible for ensuring that the Waal and Rhine bridges be blown at the right moment. Rauter met with Gen. von Wülisch of the WBN staff and they agreed to have a team of engineers from the Waffen-SS command examine bridge preparations. As a result, by September 8, the bridge charges at Nijmegen were inspected and found to be in working order with both a primary and secondary fuze, but the supplementary road charge was left in the Lent bunker to permit use of the highway bridge by retreating German forces. On September 17 following the airborne landings, Oberst Fullriede of the Fsch.Pz.Ers.-u.Ausb.Rgt. HG drove to Nijmegen to check on the deployment of his units in the city. He was shocked at the apparent lack of provisions to demolish the bridge, and noted the wiring but the lack of charges for the supplementary road charge. Guards on the bridge indicated that the Pioner team from Utrecht had not arrived and they could not detonate the charges. Following the changes in tactical command on September 17–18, Model personally insisted on making the final decision to demolish the Waal Bridge. Several senior officers telephoned Model’s headquarters on September 18 and 19 urging a prompt demolition. Model refused permission to do so, insisting that the bridge was vital for future counterattack. In spite of this, Harmel ordered his divisional engineers to ensure that the bridge was ready for demolition and they moved the road charges from the bunker back to the road surface prior to the renewed combat on September 19–20.

The main force dispatched from Wehrkreis VI to counterattack the 82nd Airborne Division around the Groesbeek Heights was Division Nr. 406, a shadow division scraped together from an assortment of units. The initial attack on September 18 disrupted the landing zones, and here a young officer gives instructions for the attack on September 19. (NARA)

By Monday September 18, Korps Feldt had arrived on the scene and began its spoiling attack from the Reichswald towards Groesbeek Heights starting around dawn. The 82nd Airborne Division was very thinly spread since it still had to defend the glider landing zones until later waves of reinforcements arrived. Company I, 3/505th PIR held Landing Zone N while Co. D, 2/508th PIR defended Landing Zone T. Feldt later admitted that he “had no confidence in this attack since it was an almost impossible task for Division z.b.V.406 to attack elite troops with its motley crowd. But it was necessary to risk the attack in order to forestall and enemy advance to the east and to deceive him in regards to our strength.” Feldt had been promised that the 3. Fallschirmjager-Division and 5. Fallschirmjager-Division would be arriving later in the day to reinforce the attack.

Division z.b.V.406 at this stage had about 3,400 troops organized into four infantry battlegroups and supported by Hptm. Freiherr von Fürstenberg’s small mobile battlegroup with five armored cars and three Flak half-tracks with quad 20mm auto-cannons. The German force outnumbered the defenders about ten to one. Kampfgruppe Göbel, built around an engineer battalion and the two battalions of the Wehrkreis VI NCO school from Wahn, made the most progress. This battlegroup pushed into the Kiekberg woods southeast of Mook. The other battlegroups consisted mainly of district alarm units manned by old World War I veterans, as well as improvised battalions of Austrian Luftwaffe ground personnel. Kampfgruppe Kretzisch and KG Stargard attacked Landing Zone N. By late morning, Division z.b.V.406 had overrun most of Landing Zone N and Landing Zone T, and had captured the ammunition dump of the 508th PIR.

Gavin responded by personally leading a counterattack with Co. D, 307th Airborne Engineers. In the early afternoon, Warren’s 1/508th PIR had returned from their short-lived attempt to seize the Nijmegen Bridge. This battalion struck the northern side of the German force, at Landing Zone T around 1310hrs and “rolled them up like a piece of tape, capturing 149 prisoners, and killing approximately 50, and knocking out 16 dual 20mm (Flak) guns.” To the south, two platoons from Co. C, 1/505th PIR, swept across Landing Zone N shoulder-to-shoulder, firing from the hip. “It looked like a line of hunters in a rabbit drive and the Germans looked like rabbits running in no particular pattern.”

Adding to the momentum of the paratrooper’s counterattack was the delayed arrival of the next wave of glider reinforcements. The plan had been to bring in the division’s artillery at 1000hrs, but the arrival had been delayed until 1400hrs after fog had closed the runways in Britain that morning. The D+1 lift included 454 gliders with three field artillery battalions, an antitank gun battery, and a medical company totaling 1,899 troops, 206 jeeps, 123 trailers, and 60 guns. By this stage, German Flak units were better prepared and they damaged many gliders and transports during the approach flight. In total, 385 gliders landed within the divisional lines. Some overshot the landing zones for a variety of reasons and ended up in Germany or away from the intended landing zones. In total, the day’s drops brought in 1,341 troops, but only 40 percent of the division’s guns.

The droning sound of the approaching transports alarmed the German troops, already hard pressed by the American counterattack. The gliders began flying into the contested landing zones while the fighting was still going on. Division z.b.V. 406’s attack collapsed into a panic-stricken rout. Feldt later recalled that “It was with the greatest difficulty that Gen. Scherbenning and I managed to halt our troops in the jump-off positions. I barely managed to avoid being captured myself in the area of Papen Hill.”

Elements of the shattered 5. Fallschirmjäger-Division were hastily dispatched to the area south of Nijmegen, and consolidated into Kampfgruppe Hermann. Here, troops are issued Panzerfaust antitank rockets on September 19 prior to the beginning of attacks against the 82nd Airborne Division around Mook. (NARA)

Later in the afternoon, Feldt was informed that the promised Fallschirmjäger divisions had finally arrived at Emmerich. He was shocked to discover that the two airborne divisions were in fact little more than two battalion-sized battlegroups, KG Becker (3. Fallschirmjäger-Division) and KG Hermann (5. Fallschirmjäger-Division) These were hasty improvisations made up of divisional rear service troops who had survived the Normandy fighting. They had few heavy weapons and no vehicles. On his return to the corps HQ near Kranenburg, Feldt was met by Model and the commander of the newly arrived II Fallschirm-Korps headquarters, Eugen Meindl. Feldt expressed his displeasure at the arrival of so measly a force after having been promised two divisions, and indicated he planned to consolidate both units into Kampfgruppe Becker and use them the following morning. Model insisted that they be sent straight into battle, but Meindl agreed that the troops were not ready after their road march and Model relented.

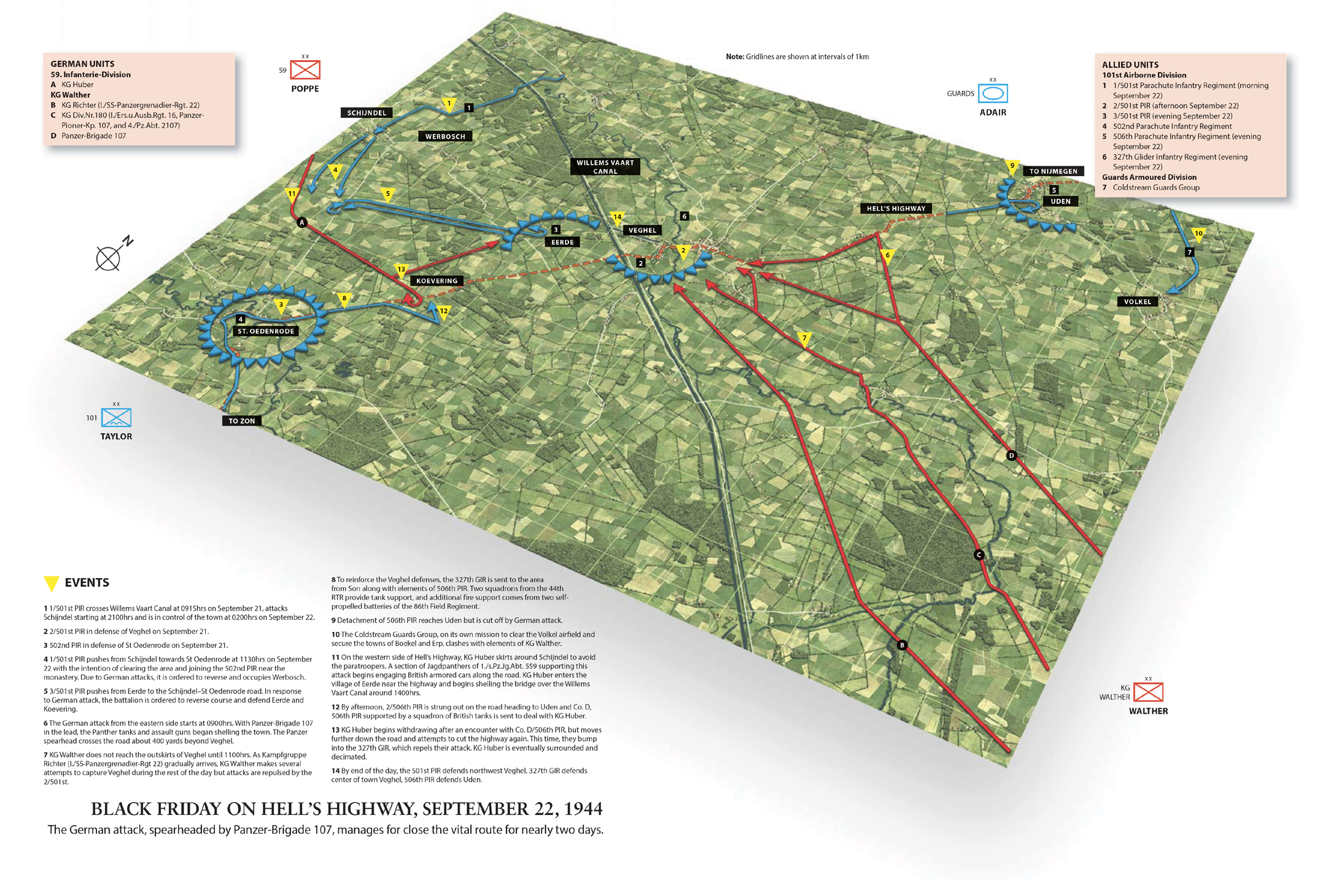

Student’s headquarters made continual efforts to interdict the highway from Eindhoven to Nijmegen in the several days after the airborne landings. The road was eventually dubbed “Hell’s Highway” for the continual fighting along the route over the course of the following week, although the British Second Army officially called it the “Cab Route.”

British lorries advance up Hell’s Highway near Eindhoven as troop transports pass overhead. (NARA)

The 59. Infanterie-Division finally arrived from AOK 15 and was sent to attack the perimeter of the 101st Airborne Division north of Eindhoven on September 19. Of its six infantry battalions, two were judged of average strength and the rest were weak or exhausted. The 59. Infanterie-Division was reinforced by assorted HG Fallschimjäger replacement units from Division Walther, about six battalions in strength, consolidated into Kampfgruppe Ewald.

The division was instructed to conduct a broad attack against the American perimeter from Son northward to St. Oedenrode and Veghel. In most cases, these made little or no inroads. On September 19, the heaviest fighting continued around Best. The 1/502nd PIR received a tank squadron from the 15/19th Hussars and at 1415hrs, launched another attack to capture the Best Bridge. The support of the British tanks proved instrumental in finally overcoming the German defenses, and by 1800hrs, the bridge site had been captured, though the bridge had been previously demolished. A total of 1,056 prisoners were captured and there were a further 300 dead from the battle. A total of 15 88mm guns were found in the defense perimeter.

The lead elements of Panzer-Brigade 107 arrived in this sector in the afternoon and at 1700hrs launched a tank attack from Helmond against the Son Bridge site along with an HG Fallschirm battalion. The attack was supposed to be supported by the 59. Infanterie-Division, but this unit contributed little to the ensuing fighting. That afternoon, a major glider reinforcement occurred which included the divisional 57mm anti-tank guns. A few of these were rushed to Son and helped repulse the German tank attack by knocking out two tanks. After the Guards Armoured Division passed along the highway to Nijmegen, some British tank squadrons were detached to support the 101st Airborne Division defenses. While these reinforcements were welcome, Taylor’s paratroopers still were stretched in a perilously thin line. His tactics were to use aggressive raiding by paratrooper battalions against German troop concentrations to pre-empt German attacks.

On September 20, Panzer-Brigade 107 attempted to interdict Hell’s Highway with tank fire and artillery rather than a direct assault In mid-morning, they hit two British ammunition lorries on the road south of Son, causing the spectacular fire seen here from the vantage point of some paratroopers of the 101st Airborne Division. (NARA)

Around 0630hrs on September 20, Panzer-Brigade 107 attacked the Son Bridge area again, which was being held by the newly arrived 327th GIR and divisional engineers. In the meantime, a tank squadron of the 15/19th Hussars with 2/506th PIR riding aboard made a tank raid against the rear of the German force, leading to a sharp skirmish around Nunen. The fighting in the Son sector continued through the day. Aggressive assaults by combined teams of British tanks and US paratroopers continued the following day with 2/506th PIR again joining in attacks with tanks from the 15/19th Hussars and 44th RTR. The strong Allied defenses around Son prompted Student’s headquarters to order Panzer-Brigade 107 to break off its attack in this sector on September 21, and move up to the Veghel area for a major new counterattack.

The German garrison in Nijmegen continued to increase after September 17 since the Waal River bridges were the most obvious route to relieve the beleaguered British 1st Airborne Division at Arnhem. On Monday, September 18, Bittrich instructed Harmel that his Kampfgruppe Frundsberg would be responsible for blocking the Waal River crossings at Nijmegen while 9. SS-Panzer-Division crushed British resistance in Arnhem.

Harmel dispatched SS-Pioneer-Battalion 10 to Pannerdern on the Waal and Neder Rijn (Lower Rhine) east of Nijmegen to establish ferry crossings, since access to Nijmegen via the Arnhem area was impossible. Sturmbannführer Leo Reinhold from II./SS-Panzer-Regiment 10 was assigned to command the Nijmegen defense, and he established a command post on the north bank of the river in Lent with a small battlegroup formed from tank crews lacking vehicles.

The defenses of the two bridges was shaped by the topographic features. The south side of the highway bridge was located on the site of the old medieval walls that had been demolished at the end of the 19th century and rebuilt into the Hunnerpark. The streets from the neighboring residential blocks fed towards the bridge through the Keizer Lodewijk Plein, a large traffic circle on the southwest corner of the park. Combined with the open spaces of the park, this created an open field of fire on the bridge approaches. There were fortified remnants of the wall still in place, a fortified chapel from the Charlemagne era, tower ruins located on the wooded Valkhof mound overlooking the west side of the park, and the medieval Belvedere Tower overlooking the bridge. The area surrounding the railway bridge on the west side of the city was dominated by the railroad marshalling yard and the high embankment leading to the bridge. As in the case of Hunnerpark, this layout provided the defenders with a clear field-of-fire against the bridge approaches.

The remnants of the old medieval walls provided the German defenders with defensive opportunities near the highway bridge. This is the Belvedere tower in Hunnerpark. This was the furthest point reached by the US patrols on September 18, and was used by Kampfgruppe Euling as an observation post during the battles on September 19–20.

The first major reinforcement to arrive in the city was another Frundsberg battlegroup under Hauptsturmführer Karl Euling from I./SS-Panzergrenadier-Regt. 22 which took up positions in front of the main highway bridge. Euling set up his headquarters in a house next to the Valkhof mound with an observation post in the Belvedere Tower. The Valkhof ruins were occupied by KG Baumgärtel, the engineer team from SS-Pio.Bn. 10 that was assigned to plant demolition charges on both Nijmegen bridges. Several 20mm auto-cannons and 88mm Flak guns from 4./Flak-Abt. 572 were moved to provide supporting fire on both sides of the bridge. Antitank defenses in Hunnerpark consisted mainly of four 50mm PaK 38 anti-tank guns, and there was at least one 75mm PaK 40 anti-tank gun on the north side of the bridge along with additional 20mm anti-aircraft guns. Four StuG III assault guns from SS-Panzer-Regt.10 were present in the area during the fighting on September 19, but appear to have moved over the north side of the bridge before the final battle. Divisional artillery was positioned on the north side of the Waal, including SS-Pz.Art.Rgt. 10 and various infantry guns; forward observers from 21. Batterie, V./SS-Art.Ausb.u.Ers.Rgt. in Nijmegen were able to direct the artillery fire with considerable precision. By September 19, there were more than 3,000 German troops in the Nijmegen area, divided between the railroad bridge, the highway bridge, and the north side of the river.

This 88mm Flak 37 was positioned near the Keizer Lodewijk Plein traffic circle, which covered access to the Nijmegen highway bridge. It is being inspected on September 21 by two lieutenants of the 505th PIR and a trooper from the Grenadier Guards. (NARA)

This Luftwaffe PzKpfw II Ausf. B was part of the original force from KG Henke of the Fsch. Pz.Ers.-u.Ausb.Rgt. HG sent to defend Nijmegen on September 17. It was knocked out on the night of September 19. (NARA)

Gavin had planned to use the 325th GIR for the Nijmegen mission, but its expected arrival on Tuesday, September 19, had been postponed again by weather. The Guards Armoured Division finally arrived in the 82nd Airborne Division sector around 1000hrs on September 19 (D+2), ready to press on to Nijmegen. A hasty battle plan was created, based in part on the mistaken view from the Dutch resistance that the “town was not strongly held and … a display of force in the shape of Tanks would probably cause the enemy to withdraw.” A battle group set out at 1100hrs consisting of the tanks of the 2nd Grenadier Guards, a British infantry company from the 1st Grenadier Guards, and Lt. Col. Ben Vandervoort’s 2/505th PIR. The plan was to proceed into Nijmegen and then break into three task forces. The main force, Column A, headed for the highway bridge, Column B aimed at the railroad bridge, and the Column C went to the main post office which the Dutch resistance mistakenly had identified as the location for the bridge demolition controls.

The Allied task force reached the outskirts of Nijmegen in the late afternoon of September 19. Column A was led by Guards Captain John Nivelle and included five Sherman tanks of the 2nd Grenadier Guards, a mounted infantry platoon from the 1st Grenadier Guards and Co. D, 2/505th PIR. The size of the German defense force around the railroad bridge was 750 to 1,000 men, about two to three times the size of the attacking force. A tank was located in the railroad marshalling yard that dominated the bridge approach, and there were several 20mm automatic cannon and at least one antitank gun. The first attack towards the railroad bridge was quickly stopped in a hail of fire. Neville sent the infantry and paratroopers over the massive railroad embankment while the tanks tried to access the approach through a tunnel. The two lead tanks were quickly knocked out, and the infantry was forced to withdraw to a small church in the area.

An aerial view of the Nijmegen highway bridge looking westward with the railroad bridge behind. Hunnerpark on the western embankment of the bridge was the center of much of the fighting on September 19–20. (MHI)

On the afternoon of September 19, one of the columns of the Grenadier Guards attempted to reach the Nijmegen highway bridge through the residential neighborhood on the southeast approaches. This Universal Carrier waits on Dr Claes Nooduynstraat while a Sherman V engages the German positions in the Keizer Lodewijk Plein traffic circle a few blocks to the west. (MHI)

Column A was led by Lt. Col. Edward Goulburn and included about 30 Sherman tanks of the 2nd Grenadier Guards, a mounted infantry company from the 1 Grenadier Guards and the rest of Lt. Col. Vandervoort’s 2/505th PIR. This headed towards the Keizer Lodewijk Plein traffic circle. Kampfgruppe Euling had set up its forward defenses in the large traffic circle. Antitank guns in Hunnerpark had clear fields of fire against the British Shermans and knocked several out in quick succession. Instead of facing a token defense, Goulburn realized he was facing a solid and determined opponent. One paratroop platoon commander recalled that “The troops within this enemy position, consisting of SS and parachutists, fought with a fanaticism never before witnessed by our veterans of Sicily, Italy, and Normandy.” The attack halted at dark around 1900hrs with plans to make a more determined attack once reinforcement arrived. Column C quickly discovered that the demolition controls were not in the post office, and this force joined Column B near the highway bridge.

A troop of Sherman tanks led by Lt. John Moller of the Grenadier Guards attempted to push out of the side streets near the Nijmegen highway bridge approach but were hit by a volley of German anti tank fire from the traffic circle. Moller’s Sherman V, seen here, was in the lead of the column and was knocked out at the corner of Dr Claes Nooduynstraat and Graadt van Roggenstraat. (MHI)

That evening, at a meeting of the senior Allied commanders, Gavin suggested that rather than try to grind through the German defenses on the south side of the bridges, it would be better to conduct a simultaneous attack on both sides of the bridges by sending a force of paratroopers over the Waal River. The 82nd Airborne Division had no assault boats, so the mission was dependent upon finding boats in the British columns south of Nijmegen and getting them to the bridgehead as quickly as possible. Gavin hoped the attack could occur that night under the cover of darkness, but the boats could not be moved forward in time.

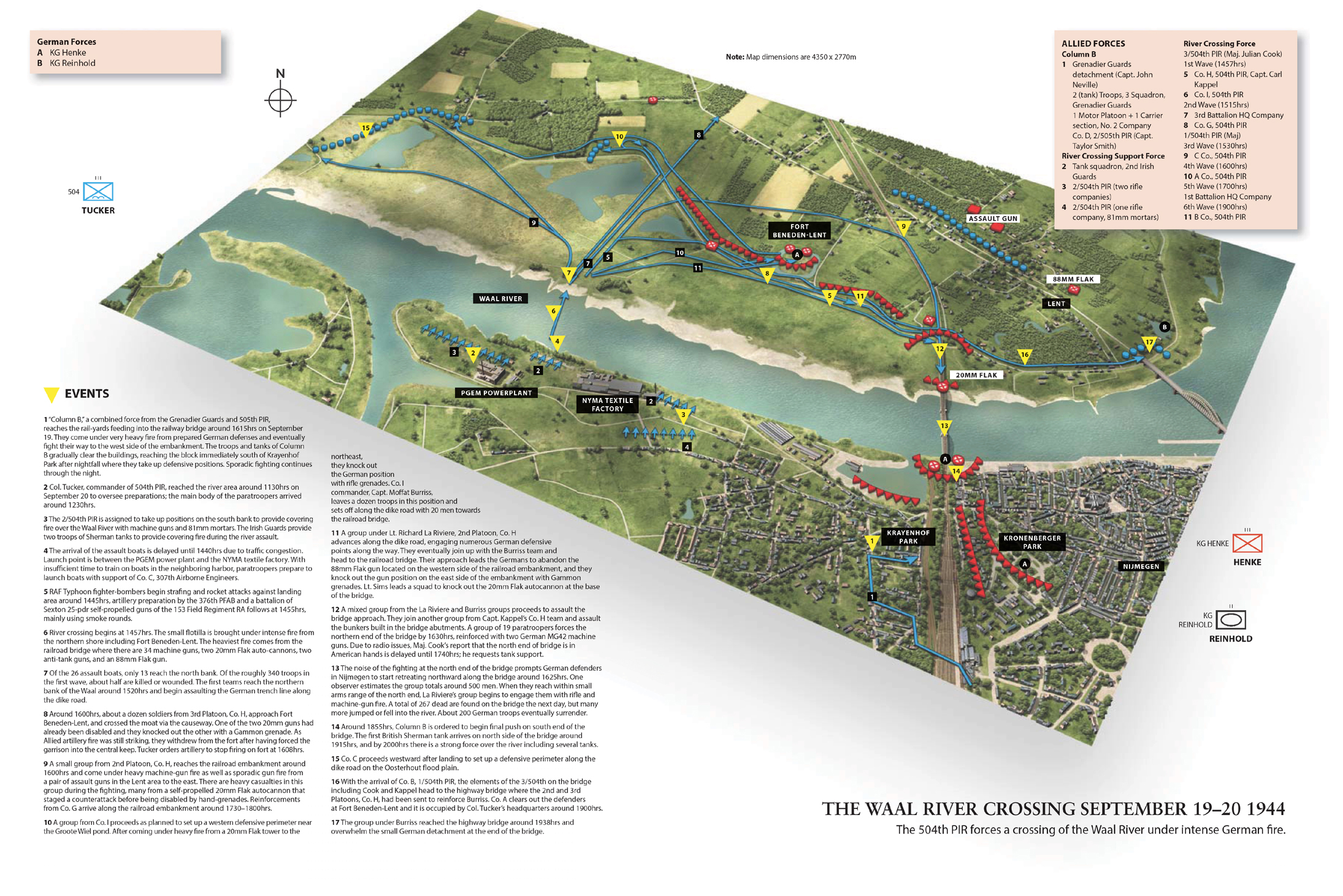

The site of the crossing was from the city powerplant west of the railroad bridge. Although German defenses in this sector were less formidable than the areas closer to the bridges, the opposite shore was covered by Fort Beneden-Lent, a 19th-century fort with a battery of 20mm Flak automatic cannon on its earthen walls. The unit assigned this daunting task was Col. Reuben Tucker’s 504th PIR, starting with two companies from Maj. Julian Cook’s 3/504th PIR and then with following waves from the other companies as boats returned. The boats were operated by troops of Co. C, 307th Engineers. The attack time was set for 1500hrs on September 20. To assist the landing, supporting artillery was organized from the 376th PFAB and a battalion of Sexton 25-pdr self-propelled guns; the 2nd Irish Guards provided two troops of Sherman tanks to conduct direct fire against targets on the north side of the river.

As the paratroopers prepared the boats behind the dike, Typhoons began a preliminary airstrike against the far bank, followed by the artillery preparation and smoke. Company H and Co. I, 3/504th PIR, ran forward and placed the boats in the water. The slow passage over the Waal took some 15 to 25 minutes, during which the fragile craft were pummeled by machine-gun, mortar, and Flak guns from Fort Beneden-Lent and the railroad bridge. Half of the troops in the first wave were killed or wounded. Once the boats landed, engineers in the boats paddled back to the other side to pick up subsequent waves of troops. In total, there were six waves sent over the river from 1457 to 1900hrs. No precise casualty figures were ever tallied for the crossing but the 3/504th PIR and 307th Engineers that day lost 36 killed, one missing, and 104 wounded. Companies H and I were down to about 90 men out of an original strength of about 240 men by the end of the day.

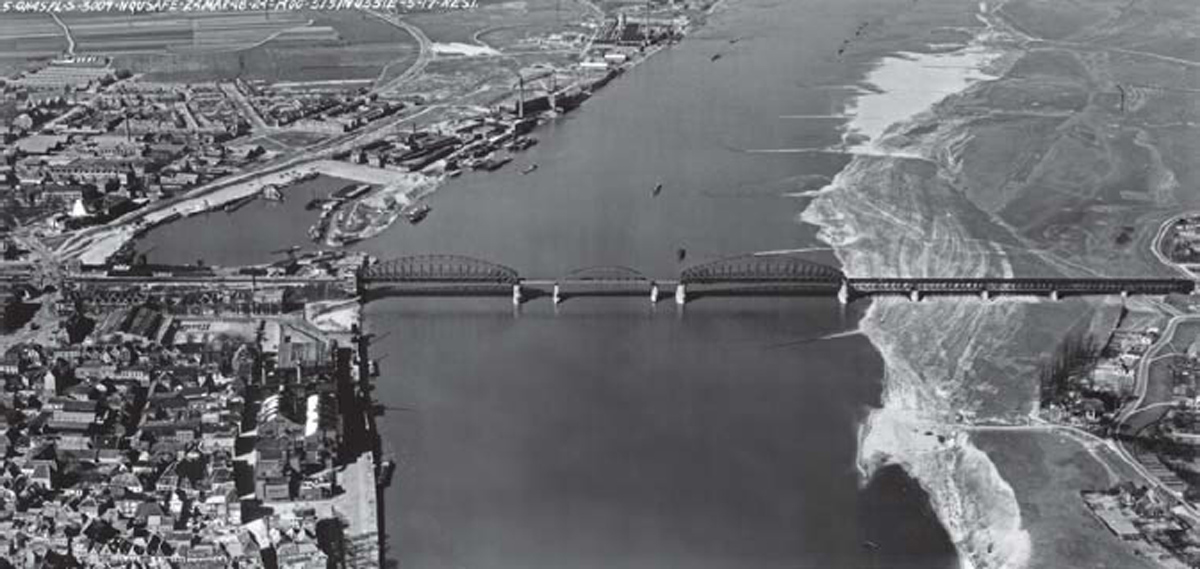

The Nijmegen railroad bridge photographed in 1946 after the damaged span was repaired. This view is looking westward and the power station used as the launch point for the river crossing by the 3/504th PIR can be seen immediately above the bridge. (MHI)

The 3/504th PIR used the British Assault Boat Mk. III for the Waal river crossing. This full-scale diorama at the Liberation Museum in Groesbeek shows a rare surviving example the Assault Boat Mk. III. (Author)

On reaching the far bank, the paratroopers fanned out towards three principal objectives – a blocking position west of the landing site, Fort Beneden-Lent in the center, and the approaches to the railroad bridge to the east. After overrunning German trenches along the dike road, a small detachment fought their way into Fort Beneden-Lent, silenced the 20mm Flak guns, and forced the surviving garrison into the keep in the center of the fort to be dealt with by subsequent waves. The largest groups of surviving paratroopers headed for the railroad bridge. The initial attacks through underpasses at the base of the bridge embankment were quickly stopped by German machine-gun defenses. However, Lt. La Riviere and five soldiers managed to reach the junction of the bridge and embankment, killing 14 German troops and capturing 20 more. The 88mm gun, anti tank gun, and bunker on the northern end of the bridge were overrun and the German defenses on the north side of the railroad bridge collapsed.

By 1630hrs, the north side of the railroad bridge was controlled by a small detachment of paratroopers. The German defenders realized that their means of escape from Nijmegen had been cut off, and Nivelle’s Column B began attacking the south side of the railroad bridge. An enormous mass of about 500 German troops began fleeing over the bridge in hopes of escaping the trap. The paratroopers set up a pair of captured MG42 machine guns on the bridge along with some BAR automatic rifles and began firing on the escaping German troops. After the initial carnage, the German attacks subsided, Capt. Kappel sent a German prisoner over the bridge to encourage the remainder to surrender. He was shot down by other German troops. As a result, the paratroopers resumed firing across the bridge. Many Germans tried to escape the slaughter by jumping off the bridge or swimming across the Waal. When the gunfire ended, the paratroopers counted 267 dead on the bridge as well as large numbers of wounded. A further 250–300 Germans were killed on the northern bank during the fighting. The British detachment counted 417 dead when they mopped up from the south side of the railroad bridge. The 504th PIR collected about 200 prisoners around both bridges that night.

An overview of Fort Beneden-Lent, on the opposite bank of the Waal River from the launch point of the 3/504th PIR assault Built in 1862, it is often called Hof van Holland in many wartime accounts due to its location. (MHI)

The assault over the Waal River on the afternoon of 20 September was delayed due to the late arrival of the assault boats caused by the traffic congestion on Hell’s Highway. The type used in the crossing was the British Assault Boat Mk. III (1), a collapsible design made from a plywood bottom and folding canvas sides. The boat was 16’ 8” long and 5’ 5” wide and weighed 350 pounds. After delivery to the launch site, the sides were erected and locked into place using folding struts hinged to the floor. The usual complement was eleven troops and two crew and standard equipment was eight paddles and a steering oar. Many of the assault boats that arrived on September 20 lacked paddles and so the paratroopers used their rifle stocks. The usual crew for the crossing consisted of three engineers from Co. C, 307th Engineers, and ten paratroopers from Company H, Company I, or the battalion headquarters company. There had been plans to train the boat crews in an inlet near the PGEM Gelderland power station, but due to the late arrival of the boats at 1440hrs, only 20 minutes before the planned start of the operation, this scheme was abandoned. This proved to be unfortunate as many of the boat crews were completely inexperienced in handling such ungainly craft in the water, and during the first few minutes of the crossing, the crews floundered around until they became accustomed to paddling and steering the boats.

Major Julian Cook had been told to expect 33 boats but only 26 arrived, reducing the side of the initial assault force. Around 1450hrs, the crews of the first wave lifted the boats on their shoulders, and carried them between the PGEM power station and the NYMA textile plant, over a dike, and into the Waal River where they were launched.

At first, there was no German reaction from the north shore, but after the boats were about a hundred yards from shore, “all hell broke loose”. The boats were targeted by the 20mm cannon on the neighboring fort, small arms fire and mortars (2). The preliminary artillery bombardment had engulfed the north shore in smoke, but the coverage was spotty and soon dissipated. The launch site was close enough to the railroad bridge that German troops on the bridge began to engage the boats as well (3). The weapons on the railroad bridge included an 88mm Flak gun, several 20mm Flak autocannons and numerous machine guns. The 20mm Flak auto-cannons had particularly gruesome effects on the unprotected paratroopers in the boat.

The river at this point was about 1,200ft wide with a strong current of about 8 miles per hour. It took the boats 15 to 25 minutes to cross the river by which time about half the troops in the first wave were killed or wounded. For example in boat No. 3 containing the Co. H commander, Capt. Carl Kappel, three were killed, five were wounded, and only three remained unscathed. Of the original 26 boats, only 11 reached the north bank and only eight returned to the south bank. By the time they reached the northern bank of the Waal River, the assault force was down to only about 120 men.

A view of the Nijmegen highway bridge on September 21 with columns of vehicles from the XXX Corps heading towards Arnhem. The commander of the 10. SS-Panzer-Division, Heinz Harmel was in the pre-war Dutch army bunker on the north bank of the Waal in the Lent suburb, identified here by the arrow. (NARA)

While the railroad bridge battle was raging, a group of about 20 paratroopers from the 504th PIR headed for the north side of the main highway bridge. After skirmishing in the suburbs near the bridge, they reached the bridge around 1915hrs and found it weakly defended. The south bank of the Waal was hardly visible due to the extensive smoke from burning buildings around Hunnerpark and the dim light at dusk.

Two days after the capture of the railroad bridge on the Waal, paratroops of the 504th PIR were relieved and sent back to recuperate. Here they are seen on walking back from the highway bridge along the Oranjesingel, with the large traffic circle off to the far left. The second trooper in the photo is believed to be Sgt. Ross Carter of Co. C, 1/504th, author of one of the earliest paratrooper memoirs from Market-Garden “Those Devils in Baggy Pants”. (NARA)

Goulburn’s Column A on the south side of the highway bridge had few details about the plan to send paratroopers across the river. As a result, they made their own plans to take the highway bridge on September 20 regardless of the river-crossing operation. Instead of attacking straight up the exposed fields south of Hunnerpark, Goulburn broke up his Guards force into three teams each based around an infantry company supported by a tank troop. Starting on Wednesday morning, September 20, they began to methodically clean out German defenses to the west of Hunnerpark to gain control of start points for a planned afternoon attack against the bridge itself. In the meantime, Vandervoort’s 2/505th PIR paratroopers cleared the area around the traffic circle and established firing positions in the buildings overlooking Hunnerpark from the south.

The final Allied attack started at 1445hrs, about the same time as the river-crossing operation to the west. The initial attack into Hunnerpark by the 2/505th PIR took heavy casualties, but eventually the paratroopers were able to overrun the trenches in the traffic circle and Hunnerpark with the vital support of the Grenadier Guards tanks. King’s Company, 1st Grenadier Guards, infiltrated through the barbed wire at the base of the Valkhof mound and was soon locked in hand-to-hand combat with the engineers of SS-Pio. Bn. 10 in the fortified ruins. No. 4 Company of the 1st Grenadier Guards assaulted the Haus Robert Janssen, the Kampfgruppe headquarters. The British infantry set fire to the house with phosphorus grenades, killing or capturing 90 troops. In the smoke and confusion, Hauptsturmführer Euling and about 60 men remained hidden in the basement and managed to exit the building and escape around 2230hrs. By nightfall, organized German defenses had collapsed, though many isolated groups continued to fight well into the night.

Around 1800hrs, 2nd Grenadier Guards tried to send some tanks over the bridge in response to a radio call from Maj. Cook near the railroad bridge requesting tank support. This was misunderstood to mean the highway bridge, but in the event, the attempt was quickly halted by antitank fire from the north bank. Around 1820hrs, about an hour before sunset, a troop of four Sherman tanks under Sgt. Peter Robinson made another attempt. The tanks ran a gantlet of fire from artillery on the north bank, German troops near the bridge armed with Panzerfausts, and a pair of antitank guns on the north end of the bridge. Two of the tanks were damaged in the charge and one was stopped on the bridge.

Allied officers on the south bank watched in grim fascination as Robinson’s tanks raced across the bridge, anticipating that at any moment, the Germans would detonate the bridge. It was not from lack of trying. Sitting in a bunker on the north side of the bridge was the commander of the 10. SS-Panzer-Division, Heinz Harmel. Model had expressly forbidden the detonation of the bridge without his explicit orders. Harmel decided to do so anyway, assuming he would face an unpleasant court-martial in Berlin if he failed to try. On seeing the Sherman tanks on the bridge, he ordered the engineers in the bunker to detonate the charges. Nothing happened.

Why the demolition charges failed to detonate remains a mystery. Jan van Hoof, a young member of the Dutch resistance group GDN (Geheim Dienst Nederland: Dutch Secret Service), claimed to have cut the wires leading to the charges on September 18. This has remained a popular legend, supported by a local commission after the war. But this explanation has been viewed with skepticism by surviving German officers and many historians. It is more likely that the detonation cabling leading from the bunker to the bridge was severed by the numerous artillery and mortar rounds that struck the bridge over the two days of fighting. It is also possible that German troops sheltering in the chambers below the bridge disconnected the cabling to avoid being blown up.

The first tank across the bridge was Sgt. Pacey’s Sherman, followed by Sgt. Robinson’s Sherman Firefly, which crushed one of the German anti-tank guns under its track. The bridge was enveloped in smoke from burning houses in nearby Nijmegen, and the scene at the end of the bridge was chaotic, with German troops firing on the Shermans from the girders above. A fifth Sherman, that of the squadron second-in-command Capt. Peter (Lord) Carrington, arrived and “some strange troops appeared and started to attack the tanks with gelignite.” Fortunately, the Gammon grenades failed to damage the British tanks. The “strange troops” were paratroopers from the 504th PIR who in the confusion, smoke, and darkness thought the tanks were German. This linkage between the British tanks and the American paratroopers occurred around 1940 hours. The next vehicle to reach the end of the bridge was a Humber light reconnaissance car of Lt. A. G. C. Jones of the 14th Field Squadron RE, who began gathering volunteers to hunt out and disarm any remaining explosive charges. Fighting continued in the chambers under the bridge after nightfall, and eventually a further 80 German troops were captured in the clean-up operation below the bridge.

Mopping up in Nijmegen continued well into night. About 60 German prisoners were captured in the Hunnerpark area; German casualties in this sector were over 400. Precise Allied casualties in the fighting for the southern approaches of the highway bridge are lacking but totaled about 200 American paratroopers and 100 British infantry and tank crewmen.

Although the senior Allied commanders were focused on the attempts to seize the Nijmegen bridges, intense fighting nearly overwhelmed the 82nd Airborne Division’s eastern perimeter again on Wednesday, September 20. Due to the delayed arrival of the 325th GIR, Gavin’s command was trying to defend a perimeter nearly 14 miles in length with an understrength division of 8,580 troops instead of 13,035.

Since the airborne landings on Sunday, Korps Feldt had continued to receive reinforcements. On Tuesday morning, September 19, two more improvised replacement divisions began arriving, Division Nr. 180 and Division Nr. 190 from Wehrkreis X. The only forces ready in the Groesbeek area on September 20 were the battered Division z.b.V.406, and the two improvised Fallschirm battlegroups that had arrived as reinforcements on September 18. The dawn attack was intended as a simultaneous action from three battlegroups against three sides of the 82nd Airborne Division perimeter. In the north, KG Becker was assigned to attack the northern portion of the Groesbeek sector, supported by the light armored vehicles of KG Furstenberg. In the center, KG Greschick, consisting of about three battalions of infantry, was assigned to attack the Groesbeek sector from two directions. In the south, KG Hermann was assigned the mission of pushing into Mook and destroying the main canal bridge near Heuman. Although of poor quality, the German battlegroups substantially outnumbered the small paratrooper detachments they were facing.

Kampfgruppe Becker launched their attack against positions of the 508th PIR in Wyler and Beek on the northeast side of the Groesbeek Heights to recapture the international highway there. Both towns had been seized by the paratroopers the evening before. Kampfgruppe Becker first attacked Co. B, 1/508th PIR in Wyler around 0845hrs. The company held out until 1500hrs. Low on ammunition, they withdrew to a small village on the hills above Wyler. After another attack later in the afternoon, Co. B requested permission to withdraw back into the main regimental defenses, and the remnants of the company arrived at the main defense line early the next morning.

In the meantime, the main body of KG Becker pushed on to Beek, held by Co. I, 3/508th PIR, and Co. D, 307th Airborne Engineers. After the town was hit by German artillery, KG Furstenberg brought up half-track-mounted 20mm Flak cannons and began raking the town with fire. The paratroopers had no weapons to counter this, and withdrew to Berg-en-Dal about 1,000 yards in the forested hills above Beek. They knocked out one of the halftracks on the winding road up the slope, blocking further half-track attacks. Gavin appeared on the scene and was told by the commander of the 3/508th that the company would have a hard time defending their new positions. German capture of this site would allow access to the east side of Nijmegen, which was in the midst of the fighting for the highway bridge. Gavin felt that his troops had an advantage over the German in night attack, and so waiting for nightfall around 1840hrs, he ordered Co. H, 3/508th, to take the town that night. The company made repeated attacks into the town that night and through the following day, with KG Becker finally withdrawing on the afternoon of September 21.

Due to constant German attacks along the Groesbeek Heights, XXX Corps provided the 82nd Airborne Division with a number of tank units for support. Here, two paratroopers of the 508th PIR, 82nd Airborne Division talk to the crew of a British Stuart light tank of the Nottinghampshire Yeomanry (Sherwood Rangers), 8th Armoured Brigade, in Beek on September 24. This unit had been assigned to the 82nd Airborne Division starting on September 21. (MHI)

Other detachments of KG Becker also attacked the defenses of Cos. A and G, 508th PIR, who were dug in on Duivelsberg (Devil’s Hill) between Beek and Wyler. The initial German attack reached to within grenade range, but was repulsed. The fighting for this hill continued for four days until September 23, with KG Becker finally giving up.

Kampfgruppe Greschick attacked the 3/505th PIR on the Groesbeek Heights near De Horst. The attack was beaten up by artillery fire from the nearby 456th PFAB and finally stopped when the battalion reserve was thrown into the line. This proved to be the least effective of the three main German attacks.

The most dangerous attack was in the south by KG Hermann that was intended to sweep through Mook and then capture and destroy the main bridge over the Wilhelmina Canal at Heuman that was supporting the XXX Corps drive into Nijmegen. Fighting had been going on since the previous evening for the control of Riethorst on the approaches to Mook, defended at the time by two platoons from the 1/505th PIR. The fighting for Riethorst continued through the afternoon of September 20 when German paratroopers finally reached the top of the hill at the center of the American defenses. The American paratroopers called in artillery fire on their own positions that blasted the Germans off the hill. While the fighting was going on at Riethorst, the main attack on Mook began on the morning of September 20 with a heavy, three-hour artillery preparation. The town was defended by two platoons of the 1/505th PIR and KG Hermann captured it around 1500hrs after about an hour of fighting. The 1/505th PIR commander, Maj. William Ekman, requested tank support from the Coldstream Guards, and a task force consisting of a tank squadron from the 1st Coldstream Guards and Co. B, 505th PIR counterattacked into Mook and retook it after dark following several hours of fighting.

The failed counteroffensive of September 20 was the swansong of Korps Feldt in this battle. This headquarters was only an improvisation, and with the arrival of the Gen. Eugen Meindl’s II Fallschirm-Korps headquarters, Feldt’s headquarters withdrew to its original defense role on the German frontier.

By the morning of September 21, the Guards Armoured Division had only a weak contingent on the north side of the Waal consisting of Robinson’s Sherman troop, reinforced by elements of the Irish Guards Group. Armored car patrols from the Household Cavalry were already over the river and reported that the Germans were establishing defenses on either side of Elst, the main town on the road from Nijmegen to Arnhem. News from the British airborne force in Arnhem to the Allied commanders was obscure due to a debilitating series of radio failures. A sapper from the 1st Airborne Division managed to infiltrate out on the night of September 20 and reach the Nijmegen bridgehead on Thursday, September 21, with news that two of the brigades were fighting hard in the Oosterbeek suburbs but that Maj. John Frost’s 2nd Parachute Battalion near the bridge was being hard-pressed by German counterattacks. Radio contact was finally established through an artillery unit that morning. It was not known at the time by Allied commanders, but by noon that day, Frost’s battalion had finally been overwhelmed and Arnhem Bridge was firmly under German control.

On the late morning of September 21, the remainder of the Irish Guards Group began moving over the Nijmegen highway bridge in anticipation of the afternoon attack into the Betuwe towards Elst. This column from B Squadron, 2nd Irish Guards, is led by a Sherman Vc Firefly named “Buncrana,” its front covered in shrimp netting for camouflage. (NARA)

Horrocks did not press the lead elements of the Guards Armoured Division to renew the attack in the morning, much to the chagrin of Gavin and Tucker, who felt that a greater sense of urgency was needed. The German commander of the Nijmegen defense, Heinz Harmel, later argued that there were no German tank forces between Nijmegen and Arnhem and that an opportunity was lost. This was not Horrocks’ perspective. In his view, the countryside north of Lent, called the “Betuwe” (Island) by the Dutch, was poorly suited to tank operations. The terrain was mainly polder, low-lying farmland that had been drained but was still too soft for cross-country tank movement. Tank traffic would inevitably be obliged to use the main roads, which were elevated above the polder and very vulnerable to interdiction by German guns. One British tanker later called it “suicide skyline.” Horrocks felt that terrain was better suited to infantry and he had already ordered the 43rd (Wessex) Division forward for the main effort. The 130rd Infantry Brigade of the 43rd Division began taking over defense of the Nijmegen bridgehead from the Guards Armoured Division shortly after noon. While Horrocks was probably not aware of it, Dutch army staff college exercises before the war included a test exercise to reach Arnhem from the Nijmegen area. Candidates proposing to use the Nijmegen–Arnhem road were failed; the correct response was to advance on Arnhem from the west, as the 43rd Division eventually did.

The Grenadier Guards Group that had spearheaded the capture of Nijmegen had become burned out in the fight for the city, and the division’s Irish Guards Group took over the role of divisional spearhead to push up the highway to Arnhem that afternoon. The push out of Nijmegen began at 1330hrs but about 2 miles from the start point it ran into an improvised German antitank screen consisting of a few StuG IIIs. The first three tanks of No. 1 Squadron were knocked out in quick succession, bringing the column to a halt short of Bemmel station. An effort to push out of the Nijmegen via the railroad bridge by the Welsh Guards Group was even more short-lived.

It was equally chaotic on the German side. A planned Frundsberg counterattack from the Pannerdern ferry-crossing site became bogged down. The reduction of the Frost’s battalion at the Arnhem Bridge freed up German troops to send down the Arnhem–Nijmegen road. By late afternoon, elements of KG Knaust including a few tanks had reinforced the defenses around Elst, further blocking the road. As Horrocks correctly had assessed, this was a task for infantry, and the 43rd Division began their assault across the Betuwe on Friday, September 22.

Even after the Allies had taken the Nijmegen Bridge, Model was convinced that their hold of the narrow corridor from Eindhoven to Nijmegen was tenuous and vulnerable to entrapment. The two British corps on either side of Horrocks’ XXX Corps had made insignificant progress in covering its flanks and the scale of German attacks on Hell’s Highway began to increase. On Thursday, September 21, Model ordered Reinhard’s 88. AK on the west side, and Obstfelder’s newly arrived 86. AK on the east, to sever the highway at Veghel. The principal forces in this attack were KG Huber from 59. Infanterie-Division on the western side and KG Walther with Panzer-Brigade 107 from the east. Model also ordered Meindl’s newly installed II Fsch.Korps to stage a simultaneous attack on the Nijmegen area around the Groesbeek Heights, but the diversion of fresh units such as Division Nr. 190 delayed a large-scale attack.

On September 22, Panzer-Brigade 107 struck Hell’s Highway between Veghel and Uden, shooting up a convoy from the 123rd Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment. Two of their wrecked lorries and two of their Bofors guns can be seen here. (NARA)

The defenses of the 101st Airborne Division were strung out along the highway from Son to Grave. Taylor tried to keep the Germans at bay by aggressive thrusts against any signs of German action. On the night of September 21, the 501st PIR pushed out the defense perimeter west of Veghel by seizing Schijndel, with plans to continue southward and meet up with the 502nd PIR north of St Oedenrode. This effort progressed well enough until the afternoon of September 22, at which point the German attacks east of Veghel forced the abandonment of this attack and the contraction of the 501st PIR back to the Veghel area to defend the key road-junction.

The German attack started at 0900hrs, with Panzer-Brigade 107 in the lead. Its Panther tanks crossed the highway between Veghel and Uden and began shelling British convoys and the town itself. After destroying several lorries, the tank column turned southward and headed into Veghel along the road. On the outskirts of town, the lead Panther was hit at close range by a 57mm anti-tank gun. Without infantry support, Panzer-Brigade 107 showed little enthusiasm for a close-quarter skirmish inside the town. In the meantime, KG Walther began its attack on Veghel from the south. This consisted of two columns. On the northeast side of the Veghel–Erp road was KG Richter led by SS-Hauptsturmführer Friederich Richter, based on SS-Panzergrenadier-Regiment 21. On the southwest side of the road was a battlegroup from the newly arrived Division. Nr. 180 based on I./Ers.u.Ausb.Rgt. 16, reinforced with elements of Panzer-Brigade 107.

The 101st Airborne Division’s artillery commander, Brig. Gen. Anthony McAuliffe, was visiting the Veghel area at the time of the German attacks and was appointed by Taylor to take over the coordination of the defense effort. He is seen here with Col. Robert Sink (center) of the 506th PIR and Col. Joseph Harper (right) of the 327th GIR. (MHI)

The first elements of Panzer-Brigade 107 had reached the Netherlands by train on the evening of September 18 near Venlo, and were immediately sent into action against the Allied bridgehead over the Son Canal. After several costly days of fighting, the brigade was ordered north to Gemert on September 21 where it was attached to Kampfgruppe Walther for the next day’s attack on Veghel. The brigade commander, Maj. Berndt-Joachim Freiherr von Maltzahn, tried to keep the brigade intact, but instead elements were broken off to reinforce weaker elements of KG Walther. So for example, the brigade’s engineer troops, Panzer-Pionier-Kompanie 2107 and the Jagdpanzer IVs of the 4./Pz.Abt. 2107 were detached to the battle-group of Div. Nr. 180 attacking Veghel from the south.

The attack on September 22 started at 0900hrs, with Panzer-Brigade 107 in the lead. At first, the brigade encountered little opposition since the countryside away from the highway was essentially a no-man’s-land. Panzer-Abteilung 2107 eventually moved to the right flank of the KG Walther, and attacked towards the road between Uden and Veghel around 1100hrs. The Panther tanks (1) encountered a column of British lorries from the 123rd LAA Regt., towing 40mm anti-aircraft guns towards Nijmegen. Several of Bedford trucks were hit and burned (2). Having overwhelmed the British column, the Panther tanks followed the road southward towards Veghel. By this time, Allied forces had reinforced the town including 57mm anti-tank guns from Battery B, 81st AAA Bn., anti tank guns and bazookas from the 327th GIR and Sherman tanks of the 44 RTR. The lead Panther tank was hit by a 57mm gun and then pummeled in rapid succession by other anti-tank guns and Sherman tank fire. The Panzer-Abteilung 2107 spearhead had second thoughts about pushing directly in to the town in view of the strong defense and its own lack of immediate infantry support. Additional attacks were launched during the course of the day, with little effect.

The fighting around Veghel continued through Saturday, September 23. During the fighting that day with Sherman tanks of the 44th RTR, the Panzer-Abteilung 2107 commander, Maj. Hans-Albrecht von Plüskow was killed as was the Panzergrenadier-Abt. 2017 commander, Hauptmann Kurt Wild. Kumpfgruppe Walther was forced to retreat back towards Gemert later in the day. On September 25, Panzer-Brigade 107 was ordered to establish a defensive line Venray–Overloon–Oploo. By the end of the month, the brigade had lost 19 of its original 36 Panther tanks and about 300 troops.

The concentration of Luftwaffe Fallschirmjäger training camps near Utrecht led to the conversion of many school units into improvised battlegroups. Here a US Army Signal Corps team brings back three German prisoners wearing Luftwaffe camouflage smocks during the fighting around Veghel on September 22. (NARA)

The attacks were repulsed by the 2/501st PIR, which received a steady stream of reinforcements during the course of the day both from other elements of the 101st Airborne Division as well as British units transiting through the town towards Nijmegen. The 327th GIR was sent to the area from Son along with elements of 501st and 506th PIR. Two squadrons from the 44th RTR provided tank support. The Coldstream Guards Group, on its own mission to clear the Volkel airfield and secure the towns of Boekel and Erp, skirmished with elements of KG Walther to the northeast. Kampfgruppe Walther committed other units to the brawl including Festung-Batalion 1409 and elements of GR 959.

To the east of Veghel, KG Huber skirted around Schijndel, aiming for the highway by way of Eerde. A section of four Jagdpanthers of the 1./s.Pz.Jg. Abt. 559 supporting this attack came in range of the highway and began firing on British armored cars traveling along the road. Kampfgruppe Huber entered the village of Eerde near the highway and began firing on the bridge over the Willems Vaart Canal around 1400hrs. Company D, 506th PIR, supported by a squadron of British tanks, was sent instead to deal with KG Huber. The Allied attack forced KG Huber to back away from the road, but they moved further down the highway in another attempt to cut it. This time, they bumped into the 327th GIR, which repelled their attack. As the weather cleared, the RAF sent in Typhoon fighters to rocket any visible German vehicles. Kampfgruppe Huber was eventually surrounded and decimated. Even though the attack on September 22 failed to capture or destroy the key bridges, it interrupted vital road traffic for almost 25 hours at a critical time when XXX Corps was attempting to push out of Nijmegen to relieve the 1st Airborne Division at Arnhem.

The attacks by Panzer-Brigade 107 on September 23 were especially costly. The Panther command tank of the leader of Pz.Abt. 2107, Maj. Hans-Albrecht von Plüskow, was knocked out by flanking fire from a 44th RTR Sherman during the fighting near the Erp road. (NARA)

Troop leader Wally Arsenault of C Squadron, 44th RTR, spotted Pluskow’s Panther near the Veghel–Erp road and his Sherman II crew fired four rounds at it, knocking it out. In the meantime, another Panther had spotted Arsenault’s tank and fired a single shot that penetrated the front of the hull. The crew managed to escape before an ammunition fire destroyed the tank. (NARA)

Model was unhappy with the lack of progress of the Black Friday attack and ordered the attack resumed the following day. Since KG Huber from the 59. Infanterie-Division had been smashed, KG Chill was brought up to take its place. This division bore little resemblance to the unit that had fought on the Albert Canal at the beginning of the month, aside from its administrative core. On September 24, it consisted of two regiments, FJ-Rgt. 6 with 2,660 troops, and KG Dreyer consisting of FJ-Battalion Jungwirth, Battalion Finsel (I./FJ.Rgt. 2) and Battalion Ohler with a combined strength of 1,585 troops. Fallschirmjäger-Battalion Jungwirth was a new addition to the battlegroup and was made up of the remnants of two battalions from the Herman Göring training regiment. Fire support came from Art.Regt. 185 with 13 105mm field guns, two 150mm howitzers, as well as 19 20mm and 15 88mm Flak guns used as field artillery.

Kampfgruppe Walther continued its attack of the Veghel but was hit by a joint US–British counterstroke along the Veghel–Uden highway. The 506th PIR pushed up the road from Veghel while the 32nd Guards Brigade moved down from Grave through Uden, meeting the paratroopers by late afternoon. Although KG Walther managed to get tanks to within 500 yards of the bridges, the late afternoon Allied attacks threatened to surround the unit. The losses suffered by KG Walther in the two days of fighting compelled their withdrawal towards Gemert. The commanders of both the Panzer battalion and Panzergrenadier battalion of Panzer-Brigade 107 were killed that day. To the west, KG Chill’s attack fizzled out because Von der Heydte’s depleted regiment was exhausted after enduring two night marches to reach the launch point at Schijndel.

On September 24, Kampfgruppe Chill, supported by three Jagdpanthers of 1./s. Pz.Jg.Abt. 559, cut Hell’s Highway near Koevering, shooting up a British column consisting mainly of lorries from the 536th RASC Company, 64th (Medium) Regiment RA, 52nd (Lowland) Division. This shows the scene the next day after the lorries were pushed off the road. (NARA)