CHAPTER 13

Great Hope of China

Marshall’s letter of resignation as chief of staff was submitted to the president two weeks before General MacArthur formally accepted the Japanese surrender aboard the battleship Missouri in Tokyo Bay. It would not be acted upon until Marshall’s successor, General Eisenhower, returned from Germany in November. During the fall Katherine sorted and packed their possessions, the accumulation of her own things plus forty years of George’s army uniforms, riding outfits, hunting and fishing equipment, boxes of papers and books, trophies, and hundreds of souvenirs, even a “canteen with water from Bataan still in it.” She and George spent evenings talking about the next phase of their lives. After moving their belongings to Dodona and preparing the place for the winter, they planned to drive to Pinehurst, where George would hunt quail. Then, a few months on the west coast of Florida, fishing in the Gulf and reading, before returning for spring gardening in Leesburg. Katherine wrote that “mentally and physically,” her husband “was a very weary man.”1

Marshall delivered his farewell remarks at a ceremony attended by the president in the center courtyard of the Pentagon on November 26, 1945. Premised on what he called “the genius of America” and “the strength of a free people,” Marshall marked a sharp departure from prewar isolationism and glimpsed a new world order. “I am certain,” he said, that the United States “desires to take the lead in the measures necessary to avoid another world catastrophe . . . And the world of suffering people looks to us for such leadership.” His closing lines charged the next generation of Americans with a duty and a responsibility. “It is to you men and women of this great citizen-army who carried this nation to victory, that we must look for leadership in the critical years ahead. You are young and vigorous and your services as informed citizens will be necessary to the peace and prosperity of the world.”2

The next day George and Katherine left Quarters One for the last time, leaving the chickens and the henhouse in their yard to Dwight and Mamie Eisenhower. With Marshall at the wheel of their prewar Plymouth they drove out Route 7 to Leesburg, “full of our own thoughts and plans,” wrote Katherine. From a gas station just outside the entrance to Dodona Katherine heard a jukebox blaring out a 1920s popular song that her children and their friends used to dance to at Fire Island. She “began to hum the refrain,” but stumbled over the words. “Sing hallelujah, hallelujah / And you’ll shoo the blues away . . .”3 When they entered the gate, Katherine recalled, “George looked at me and smiled.”4

After a few hours of emptying the car and unpacking with the help of George and her daughter, Molly Winn, who had been staying at Dodona, Katherine announced that she was going to take a nap before dinner. Halfway up the front stairs she heard the phone ring. Out of earshot, Marshall answered it in his downstairs office. The White House operator announced that the president wished to speak with him. Truman’s post-presidency memoir purports to report the entire conversation. “Without any preparation,” wrote Truman, “I told him: ‘General, I want you to go to China for me.’ Marshall said only, ‘Yes, Mr. President,’ and hung up abruptly.”5

Marshall must have been forewarned about the background of the president’s request and what it would mean for him. Otherwise, Truman’s recounting of the extremely brief conversation is unbelievable, coming as it did on the day after Marshall retired. Suspecting that Molly knew that Truman had called, Marshall told her that he would shortly be going to China and asked her to keep it to herself for the time being. He wanted to pick the time and place to tell his wife about his new assignment. Later, Katherine came down from her nap. By happenstance, the radio was turned on then or during dinner. Katherine heard the breaking news: “Mr. Hurley resigns. President Truman has appointed General of the Army George C. Marshall as his Special Ambassadorial Envoy to China. He will leave immediately.” Katherine was shocked, “rooted to the floor,” she wrote. Marshall put his arm around her. “That phone call,” he said, that came in as she was going upstairs, “was from the President. I could not bear to tell you until you had had your rest.”6 Two days later when Truman asked Marshall about Katherine’s reaction, he said, “There was the devil to pay.”7

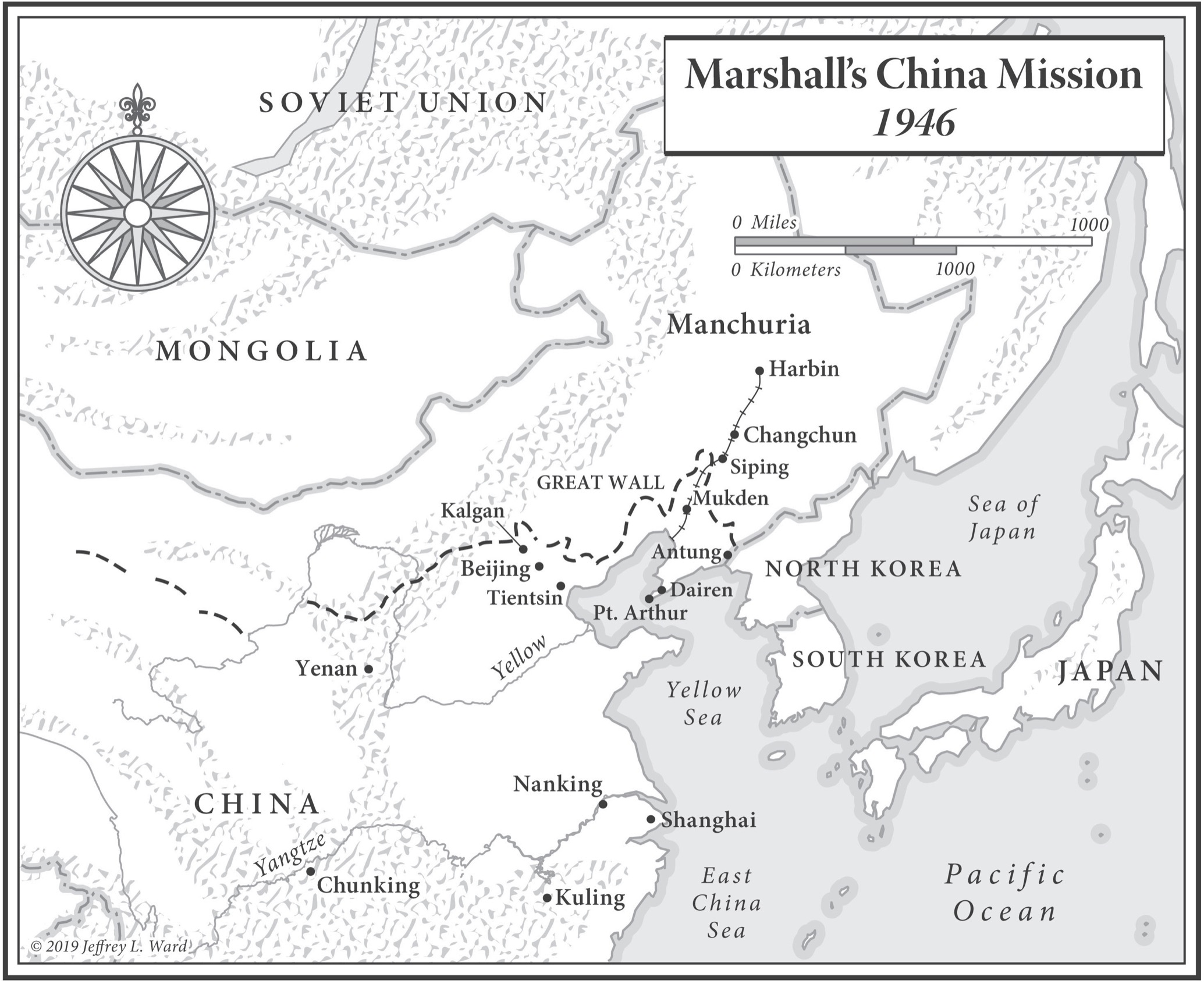

Marshall in fact did have an idea of why the president suddenly called him and asked him to go to China. As chief of staff he had received pessimistic reports throughout the fall from General Wedemeyer, commander of U.S. forces in the China theater, warning that civil war between the Nationalist army of Chiang Kai-shek and Mao Zedong’s Communist forces in pockets of north and central China had intensified and that the Soviet Union, with the Red Army still occupying parts of Manchuria, was providing arms and other assistance to the Communists. The United States faced the possibility of being drawn into the Chinese civil war and conceivably an armed confrontation with the Soviets, who were vying with the U.S. for postwar influence, if not dominance, in East Asia. Efforts by American diplomats to negotiate a cease-fire and unification of China by peaceful methods had failed. Consequently, Marshall knew that a military and diplomatic crisis in China was in the offing. However, unless he had been tipped off by Secretary of State James Byrnes, he was probably not aware of what had transpired in Washington behind closed doors in the thirty hours or so before Truman phoned him at Dodona.

Sometime before three p.m. on Monday, November 26, while Marshall was at the Pentagon for his retirement ceremony, the U.S. ambassador to China, Patrick J. Hurley, who was in Washington for consultations, informed Byrnes that he did not want to return to China and was thinking of resigning. The secretary urged him to stay on and told him the country needed him. Byrnes came away from the conversation thinking he had persuaded Hurley to return to China. He should have known better. Hurley, born in the Choctaw Nation in Oklahoma, was a real estate and oil and gas millionaire, a staunch Republican who had served as President Hoover’s secretary of war. He was appointed ambassador to China by Roosevelt in 1944, but he had proven to be increasingly erratic, reckless, and unreliable, famously having greeted Mao and others on more than one occasion with the Choctaw war cry “Yahoo!” He was prone to drunken rants, and quarreled with Wedemeyer so often that the general sent cables to Washington questioning Hurley’s sanity. Hurley’s colleagues at the embassy in Chungking urged the State Department to fire him for incompetence. Dean Acheson’s characterization of Hurley was apt: “Trouble moved with him like a cloud of flies around a steer.”8

Though there is no supporting record, Truman claimed in his memoir that he met with Hurley in the White House at 11:30 a.m. the next day about the “seriousness of the situation” in China and that Hurley assured him that he would “wind up a few personal matters and then return to China.”9 Later, during his weekly cabinet luncheon, an aide handed the president a scrap of yellow news copy that had been torn off the White House ticker tape machine. According to Secretary of Commerce Henry Wallace, Truman glanced at the news flash, held it up, and angrily said, “See what a son-of-a-bitch did to me?”10 Without informing the president, Hurley had released to the press a scathing letter of resignation, dated the day before, claiming that “career men” in the State Department continuously undermined his efforts to support the Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek by siding with “the Chinese Communist armed party” and “the imperialist bloc of nations” whose policy it was to keep China divided against herself. He warned that “[t]here is a third world war in the making.”11 Hurley’s allegations of unnamed Communist sympathizers in Truman’s State Department were explosive. He was among the first to plant the seeds of McCarthyism and Red-baiting that consumed U.S. politics in the 1950s.

“To me,” wrote Truman, the letter “was an utterly inexplicable about face, and what had caused it I cannot imagine . . .”12 Worried about the political damage that Hurley’s allegations would cause, Truman polled his cabinet. All concurred that Hurley would have to go. Clinton Anderson, secretary of agriculture, recommended that the president immediately appoint General Marshall as new special ambassador to China, a move that would steal the headlines from Hurley. Two or three hours later Truman called Marshall at Dodona. On the following day, Hurley gave a press conference at the National Press Club at which time he named names. By that time the news that Marshall was his successor was out.

It was understood that Marshall could not depart for China until he finished his testimony before the Joint Committee that was investigating the Pearl Harbor attack. While he was busy testifying he asked Secretary Byrnes to prepare specific written instructions to govern his mission. Byrnes had already articulated his overall view: Marshall should use U.S. economic and military aid as leverage to “force” Chiang to negotiate a cease-fire and form a coalition government with Mao’s Communists.13 Byrnes delegated the task of drafting detailed instructions to Undersecretary of State Acheson and John Carter Vincent, the State Department’s expert on China policy (one of Hurley’s “superiors” that he complained about in his letter of resignation). Marshall rejected their initial draft, saying it lacked clarity and would not be understood by the American public. He insisted on revising it with the help of a few trusted army officers. During periods when Marshall was not testifying, Acheson worked with Marshall for hours to talk through and hammer out language acceptable to the State Department and Marshall. Acheson had encountered Marshall’s way of thinking during the war, but he had never been exposed so intimately to what he called in his memoir “the art—of judgment in its highest form. Not merely military judgment, but judgment in great affairs of state, which requires both mastery of precise information and apprehension of imponderables.”14

On December 14, Marshall and acting Secretary of State Acheson (Byrnes was on his way to Moscow) met with Truman to finalize the documents that governed Marshall’s mission. They consisted of a statement of United States policy with respect to China, a memorandum for General Wedemeyer, and a press release. The policy document made it clear that the U.S. would not intervene militarily to influence “Chinese internal strife.”15 A cover letter, which Truman signed in their presence, summarized Marshall’s charge, as follows: broker a cease-fire; persuade Chiang to convene a national conference to bring about the unification of China under a coalition government that included the Chinese Communist Party; complete the evacuation of Japanese troops from China; and withdraw American armed forces (i.e., 50,000 U.S. Marines) from China.16 It was a challenging assignment, to say the least. As an incentive, Marshall was authorized under the policy document to offer U.S. economic and military assistance to the Nationalist government as “China moves toward peace and unity.”17 The power to grant or deny aid to the Nationalists was the only real leverage Marshall could use to influence the behavior of the two parties.

There were two provisos, not mentioned in the cover letter, that undermined Marshall’s status as an impartial mediator. The first was contained in “notes” of a conversation between Truman and Marshall in which it was understood that if the mission should fail, the Truman administration would “continue to back” Chiang’s government.18 The second, buried in the China policy document, stated that since Chiang’s Nationalist government was the only “legal government in China,” it was “the proper instrument”—that is, the only instrument—“to achieve the objective of a unified China.”19 The latter proviso meant that the Communists would be at best a minority voice in a unified China ruled by Chiang. The former, which Chiang became aware of via a leak in Washington, was akin to a guarantee.20 No matter how unreasonable or obstructionist in negotiations, Chiang could fall back on the support of the U.S. government.

The next day, Katherine and John Carter Vincent accompanied Marshall to National Airport. As Marshall’s plane taxied out onto the runway Vincent turned to his ten-year-old boy and said, “Son, there goes the bravest man in the world. He’s going to try and unify China.”21 Katherine had a different reaction. In a letter to Frank McCarthy, she wrote, “When I saw his plane take off without anyone to be close to him . . . I felt I could not stand it . . . I give a sickly smile when people say how the country loves and admires my husband . . . I know just how he felt too, but neither of us could speak of it because it was too close to our hearts . . . This sounds bitter. Well, I am bitter. The President should never have asked this of him and in such a way that he could not refuse . . . and now my daily prayer is that he can bring some sort of unity out of chaos somehow.”22

It took Marshall’s C-54 almost six days and five refueling stops to hop across the Pacific to Shanghai. On his last layover before reaching China’s east coast, Marshall spent an evening with MacArthur at the embassy in Tokyo. In Reminiscences, MacArthur wrote that the general, about to reach the age of sixty-five, “had aged immeasurably” since they were last together in Papua New Guinea at the end of 1943. “The war had apparently worn him down into a shadow of his former self.”23 As usual, MacArthur was given to dramatic overstatement.

During the flight Marshall’s aides, James Shepley, a correspondent for Henry Luce’s Time magazine, and Colonel Henry Byroade (nicknamed “Side Street”), a West Pointer who had spent forty months in China, provided him with a “preliminary estimate of the political situation in China.” It was hopeful. According to their report, Chou En-lai, the Communist’s chief negotiator, had just returned to Chungking, the temporary wartime capital of China, where Chiang and the Kuomintang (KMT)—literally translated as the National People’s Party—were headquartered. The KMT and its armed forces, led by Chiang, often called the Nationalists, controlled the rich and heavily populated provinces in the south. The other main political party, Mao Zedong’s Chinese Communist Party (CCP), was based more than 500 miles to the north in the old walled city of Yenan. As Marshall’s aides reported, the fact that Chou En-lai and his delegation were in Chungking was a positive sign because they had come to begin deliberations of the Political Consultative Council, an organization sanctioned by Chiang that would bring together the KMT, the CCP, and the other political factions in China. The council’s lofty goals were to stop the fratricidal warfare, end one-party rule by the KMT, decide on a framework for constitutional government, and convene a national assembly. Shepley and Byroade advised Marshall that the council was proceeding “in a more conciliatory manner” and “in a better atmosphere than has existed heretofore.” They suggested that this was due to Marshall’s appointment and “Truman’s public statement” announcing the Marshall mission.24

Marshall was skeptical. During the war he had been on the receiving end of a blizzard of caustic complaints about Chiang from General Stilwell, the chief of staff of Chiang’s nationalist armed forces. Typical was a memo that Vinegar Joe wrote to Marshall in 1944. “The only thing that keeps” China “split” is Chiang’s “fear of losing control. He hates the Reds and will not take any chance on giving them a toehold in government.”25 As for the attitude of Mao and the CCP concerning unification, Marshall was similarly pessimistic. Shortly before leaving for China he wrote a note to Admiral Leahy saying he expected “the Communist group [to] block all progress in negotiations as far as they can, as the delay is to their advantage.”26

Marshall’s doubts were reinforced by his experiences in China in the 1920s and his knowledge of events since the 1911 revolution inspired by Dr. Sun Yat-sen, namely Chiang’s Northern Expedition and purge of the Communists in 1926–28; the Long March to Yenan in the mid-1930s led by Mao Zedong; the cessation of hostilities between the Nationalists and the CCP when the Japanese invaded; and the resumption of fighting after it became clear that Japan would lose the war. As a young army officer in Tientsin, when Chiang was securing nominal allegiances with warlords in the north, Marshall had expressed prophetic views on the future of U.S. relations with China. “How [foreign] Powers should deal with China, is a question almost impossible to answer,” he wrote General Pershing.27 Staring out the window on the long flight across the Pacific in December 1945, Marshall, as one of the “Powers” he referred to so long ago, must have realized the enormity of the challenges that lay ahead.

“Everybody scurries around here not doing much of anything, but with the impression of great accomplishment, and all scared to death over the impending arrival of the great man himself.” John Melby, a young American foreign service officer, scribbled this note of anticipation in his diary the day before five-star General Marshall landed in Shanghai.28 Like many of his colleagues at the embassy, Melby believed expectations were unrealistically high. When Marshall stepped off his plane at Shanghai’s Ganzhou Airport on December 20, he and his small staff were greeted by General Wedemeyer, commander of American forces in China, and two lines of uniformed Chinese and American honor guards. After reviewing the soldiers, Wedemeyer and Marshall climbed into the backseat of a black Buick sedan and sped downtown to the famous Cathay Hotel on the Bund, the eleven-story art deco masterpiece built by Sir Ellice Victor Sassoon, who led the real estate boom that transformed Shanghai into the Paris of the Far East.

By 1945, the Cathay had lost a bit of its luster, having been tarnished by bombing attacks and years of Japanese occupation. After settling into rooms in the tower section, Marshall summoned Wedemeyer and Walter S. Robertson, the American embassy’s chargé d’affaires, to explain his mission and to be briefed on the military and political situation. Years later, Wedemeyer and Robertson separately recalled their meeting with Marshall that began in his rooms and continued through dinner downstairs. While each remembered telling Marshall that it was “not possible” for him to achieve the main goals of his mission—a coalition between the Nationalists and the Chinese Communists and an end to the civil war—their recollections of Marshall’s reaction to their negative assessments were starkly different. Robertson, a Richmond investment banker turned diplomat, recalled that Marshall “listened very carefully to what we had to say,” and “asked questions,” but he did not reveal how “he evaluated” their disheartening views.29 By contrast, Wedemeyer wrote in his 1958 book, Wedemeyer Reports!, that “Marshall reacted angrily and said: ‘I am going to accomplish my mission and you are going to help me.’” To Wedemeyer, it appeared that Marshall did not want to hear the truth. Wedemeyer further wrote that during dinner Marshall “continued to show his displeasure.” He attributed Marshall’s foul mood and resistance to expert advice to his belief that fatigue and the “heavy toll of the war” must have worn down Marshall’s “physical condition and his nerves.”30

It is possible, of course, that Wedemeyer’s memory was accurate and Robertson’s was not. However, it is more likely that Wedemeyer mischaracterized Marshall’s reaction and mental state in order to align them with one of the main themes of his book—the failure of Marshall to “understand the nature and aims of Communism in general and of the Chinese Communists in particular.” By the end of the 1950s when he wrote his book, Wedemeyer was a card-carrying member of the “China Lobby,” part of the crowd that blamed Acheson, Truman, Marshall, and the so-called communist sympathizers in the State Department for “losing China.”31 Marshall told his interviewer in 1956 that Wedemeyer “had developed an obsession” and was not acting rationally on the subject of Communism. “Got into politics,” he said with evident derision. Coming from Marshall, it was the ultimate sin that an army officer could commit.32

The next day Marshall, Wedemeyer, and Robertson flew to Nanking to meet with Chiang, often referred to as the Generalissimo, and Madame Chiang Kai-shek. It was a short trip, about 168 miles by air. Nanking sits on the floodplain of the Yangtze River, surrounded by an ancient wall bearing the “chop” of the Ming dynasty. Large sections of the wall were in disrepair in late 1945 due to Japanese bombs and artillery shells. In 1937, Nanking was Chiang’s capital city, with a population of 1.5 million. It was then and there that the infamous “rape of Nanking” took place. Over a two-month period, some fifty thousand Japanese soldiers bayoneted, hacked, burned, disemboweled, raped, machine-gunned, buried alive, and otherwise murdered tens of thousands of residents, some say as many as 300,000. By the end of 1945, the population was half of what it had been. However, visitors were “impressed by the amount of building” going on in the city as residents who had fled the Japanese began returning.33 People in the surrounding area and an increasing number of tourists once again flocked to Nanking’s most prominent building, the mausoleum of Sun Yat-sen, which remained intact outside the city wall on the slopes of Purple Mountain. The Lincolnesque memorial to the founder of modern China looked almost the same as it did in 1929 when it opened.

Marshall and his party were met at the airport in Nanking by the Generalissimo and Madame Chiang. Marshall had not seen the couple since the Cairo conference in late 1943. At age fifty-nine Chiang’s mustache and eyebrows had begun to turn gray. Otherwise, he did not seem to have aged. There were few lines on his ascetic face. His dark eyes were alert and piercing. His clean-shaven skull gleamed. As always, he was slim, modestly attired in an army uniform bereft of ribbons and medals. In important ways Chiang and Marshall shared similar attributes. Both were introspective, reserved, and personally incorruptible. They valued duty, honor, and love of country. As young army officers they practiced self-control and discipline. (One of Chiang’s teachers at the Dragon River Academy recalled Chiang’s morning ritual. Upon rising in the morning he would stand outside his bedroom for thirty minutes, “lips tightly pressed,” and concentrate “on his goals for the day and in life.”34) They each rose to the top by cultivating career-altering mentors—Chiang to Sun Yat-sen and Marshall to Pershing—yet they were not afraid to passionately disagree with them. The Generalissimo and the American General were charismatic leaders of men.

Soong Mayling, known to Marshall as Madame Chiang Kai-shek, was unique, one of the most influential women of the twentieth century. Unlike Marshall and her husband, Madame Chiang was outgoing and garrulous, born to extraordinary wealth. Eleven years younger than Chiang, she was attractive and sexy, almost always wearing makeup and a traditional qi pao dress that was slit to the knee and sometimes above. Soong Mayling was a Christian, a devout Methodist, who had been educated in America, first at Wesleyan College in Macon, Georgia, then at Wellesley in Massachusetts so she could be close to her brother, T. V. Soong, who was at Harvard. She spoke perfect English with a Georgia accent. Mayling and Kai-shek were known throughout the world as symbols of Chinese bravery and dignity. She spent the last fourteen months of the war living on the Long Island estate of H. H. Kung, supposedly a direct descendant of Confucius, who was married to her sister Ai-ling (her other sister, Ching-ling, was the widow of Sun Yat-sen). During that time Madame and the ten lobbying firms on retainer by the Nationalist government worked to create and build a pro-Chiang, anti-Communist movement in the United States—part of the China Lobby.

Marshall’s trust in and regard for Chiang when he landed in Nanking to begin his mission to China are difficult to assess. He swore to his interviewer that he always was “fond” of Chiang and that his views toward him were not influenced by Stilwell. Marshall said he believed Chiang was not “personally corrupt,” but “there were many corrupt people around him” and his advisers “constantly sold [him] down the river.” Yet in the same interview, he claimed that Chiang “betrayed me down the river several times during the war.” It was “Madame,” he made clear, who during the war “was always for me against the generalissimo.”35 This comment surely referred, at least in part, to the fact that Madame, as well as her two sisters, supported Marshall in 1944 by pressing Chiang to retain Stilwell as his chief of staff. It is safe to say that by the end of 1945, Marshall had no objection to spending a good deal of time with Chiang, but he was not sure the Generalissimo could be trusted, especially when Madame was absent.

On the evening of December 21, Marshall arrived at a small two-story brick house in the compound of the Nationalist army headquarters to meet with the Generalissimo and Madame Chiang, his first as a diplomat. Chiang was probably nervous, mindful of Stilwell’s contempt for him and aware of Marshall’s close relationship with Stilwell. Chiang need not have worried. The name “Stilwell” was never uttered or even implied. Marshall was remarkably humble and deferential. He stressed throughout the two-and-a-quarter-hour session that he was there to listen and that he had much to learn. As to substance, he said U.S. assistance for the “rehabilitation of China” would be dependent on concessions made by each party that would lead to a peaceful settlement. However, he tilted toward Chiang and the Nationalists by saying that the solution lay with the Communists, who needed to “relinquish autonomy” over their army in order to earn “sympathy in the United States.” This was what Chiang and Madame wanted to hear. Chiang’s response to Marshall’s remarks focused more on the importance of eliminating the Communist army as an autonomous force than on the details of forming a coalition government. In addition, while warning Marshall that the Communists would try to “play [him] for time” so they could strengthen their military position, a stratagem that Marshall was keenly aware of, Chiang hinted that he had a similar aim. Through Mayling as translator, Chiang told Marshall that he planned to move additional troops into “North China,” so as to compel Mao’s CCP to “resort to political means” to reach a settlement. In other words, he too intended to use Marshall’s mediation process to strengthen his position on the battlefield, thereby increasing his ability to wield the upper hand in negotiations leading to a so-called coalition government. When Chiang tried to persuade Marshall that the Soviets, despite appearances and a treaty with the Nationalists, were actively frustrating his generals’ efforts to move their forces into North China, Marshall demurred, saying he wasn’t ready to impugn Soviet actions and motives. He ended the meeting by assuring Chiang that, on the basis of his previous “personal dealings” with Stalin, he could get the straight story from the Soviet leader himself.36

For Kai-shek and Mayling it was an auspicious beginning, an evening that ended with dinner and a toast to Marshall’s forthcoming birthday.

The next morning, Marshall, the Generalissimo, and Madame Chiang flew together to Chungking, the wartime capital located in southwest China, to meet with Chou En-lai and other top CCP officials who were there to help set up the Political Consultative Council (PCC) with the KMT. When they touched down at about noon they could see that large delegations of CCP and KMT party members were waiting to greet them. John Melby, the advance man from the U.S. embassy who was on the tarmac, wrote that because of harassment by the Nationalist police, “the mood” among the Communists “was anything but joyous.” As Marshall and Chiang emerged from the plane into the windy and raw cold, they were each “grim and unsmiling,” wrote Melby, and Marshall looked “tired.”37 Marshall spoke briefly to Chou En-lai, but was unable to understand the interpreter because his ears were blocked due to the landing. He departed without delivering remarks to the crowd, leaving it to Shepley to handle press questions. Chiang stayed behind to chat with members of the KMT and to stiffly acknowledge the presence of Chou and his CCP comrades.

To mark Marshall’s arrival in Chungking for the American press, Madame Chiang offered a positive, though not particularly optimistic, comment. “I wish him every success. He is an able and forthright man.”38

Chungking was a city in transition. Its heroic legend, earned through years of relentless bombing of its defenseless residents, was fading. Thousands of government workers were scheduled to move to Nanking in the spring, leaving in their wake the stench of corruption, profiteering, the ravages of inflation, and hundreds of alcohol-fueled lend-lease buses. Yet Chungking was blessed by natural beauty. Situated on a promontory above the junction of two major rivers, the city is encircled by soaring mountains. During the war the population had doubled, growing to more than a million. The mayor and planning commission were anticipating substantial growth, with plans on the drawing boards in early 1946 for two major bridges, tunnels, funicular railways, roads, factories, and office buildings to replace the jerry-built government shacks.39

From the airport Marshall was driven to his temporary headquarters, a cramped two-story building, sarcastically called “Happiness Gardens,” where he and his staff were to reside and conduct business. The living room on the first floor had been converted into a conference room. A desk for Marshall was placed in the hall and his bedroom was in one of two small rooms at the rear. The second floor was set aside for the staff. Marshall settled in and prepared for his meeting the next afternoon with Chou En-lai and two of his CCP colleagues.

Marshall had been briefed. He knew that Chou was the official “face” of Mao’s Communist Party in Chungking, having lived in the capital city off and on during much of the war. And he was relieved to know that Chou spoke excellent English (Marshall’s ability to understand the conversational Chinese that he learned when he was stationed at Tientsin had long since atrophied due to lack of practice). Chou had been born into an upper-class family of scholars in 1898. He was worldly, sophisticated, and socially adept. He attended elite schools in China, studied Marxism, and traveled throughout Europe in the early 1920s, spending the most time in Paris, where he joined the Communist Party. In Chungking during much of the war, Chou cultivated American diplomats and journalists, persuading many of them that the Chinese Communists were enlightened reformers and that right-wing elements of the KMT party were corrupt and treacherous. What Marshall was not told was that Chou was ruthless, with a hidden history of murder and revenge. In the late 1920s and early 1930s, Chou controlled Teke, the CCP’s intelligence agency and its “Red Squad” that tortured and assassinated KMT intelligence agents and those in the CCP suspected of disloyalty. Theodore White, prominent correspondent for Time who lived in Chungking from 1941 to 1945, was one of the journalists originally seduced by Chou. Much later he wrote that Chou was a man “as brilliant and ruthless as any the Communist movement has thrown up in this century.”40

In his first meeting with Marshall, Chou proved for the most part to be a deft negotiator. At the outset, Marshall stressed the “urgency of an early agreement” for a unified government and the need to end the “existence of two armies in China.” Relaxed and engaging, Chou responded with an offer that seemed on its face to be more than reasonable. He said he was prepared to “guarantee” that his side would “cease firing.” If the Nationalists reciprocated, “the war can be stopped.” The optics of Chou’s opening move were good. However, Marshall knew that it was in the interests of the Communists to stop the fighting because they were losing on the battlefield and needed a substantial pause to recruit fresh troops and replenish supplies. Chou might be playing him and the Nationalists for time. As for the integration of the two armies into one, Chou said that effort would, of course, have to await the formation of a “coalition government.” Once formed, the new government would unify not only “the political administration of China, but also its troops”—that is, its two armies. To sweeten his proposals Chou agreed that Chiang should remain as sovereign and the KMT “would be in first place” in the new government.

Chou’s proposals must have struck Marshall as reasonable starting points. While they could be nothing more than stalling tactics, Chou had adroitly shifted the burden to Chiang. With Marshall pressing for an early settlement, Chiang would have to respond with something other than a flat refusal to negotiate. Marshall was encouraged, but he voiced no opinion.

Chou should have stopped when he was ahead. Instead, in a transparent attempt to ingratiate himself with Marshall, he closed the meeting by claiming that the CCP desired an “American style” democracy. He suggested that the new China would emulate the spirit of “independence” of George Washington, a government by and for the people preached by Lincoln, and the “four freedoms” proclaimed by FDR. Chou misread his man. After listening to this paean, Marshall must have questioned Chou’s sincerity or his judgment, or both. Nevertheless, he was gracious. Marshall proposed a modest toast: “To a generous understanding.”41

Chiang and his advisers wrestled for a week on how to respond to Chou’s proposals. Their initial draft, presented to Marshall on the night of December 30, was anything but generous. “For the first time,” wrote Marshall, he weighed in with his own opinion. The next afternoon, Marshall’s sixty-fifth birthday, Chiang’s foreign minister, Dr. Wang Shih-chieh, drove out to Chiang’s cottage in the country where Marshall was staying. As a result of Marshall’s suggestions the night before, the Nationalist government decided to respond to Chou by proposing: (a) an immediate cease-fire; (b) appointment of a “Committee of Three,” consisting of Marshall, Chou, and Chiang’s designee, to oversee enforcement of the cease-fire and disarmament of Japanese troops; and (c) a commission to visit disputed areas in the north in order to “determine facts and make recommendations.”42 Marshall was pleased with their proposals. He started planning for the establishment of an executive agency to administer the proposed truce.

As Marshall knew, the cessation of hostilities was the easy part. Both sides could agree to an armistice, at least for a limited time, while unification was pursued. The hard part was to negotiate an agreement to deal with troop movements after the fighting stopped. Parties needed to be prevented from using the truce to gain an advantage, which they could exploit when the cease-fire ended either by its terms or by breach. To solve this problem, the Nationalists and Communists agreed that in most provinces of China their combat units would remain in the positions they were in as of the effective date of the cease-fire. However, the three northeastern provinces of China, a region known as Manchuria, were a major stumbling block. In late 1945, long after the Japanese surrender, many of the main cities and towns of Manchuria were still occupied by the Red Army. The Nationalists, as the recognized and legitimate government of all of China, were entitled to establish sovereignty in Manchuria by moving their troops and administrators into the cities and towns in the region. Moreover, by the terms of a Sino-Soviet treaty, the Soviets agreed that as they withdrew their forces from Manchuria they would help the Nationalist government move in. The problem was that the CCP was strongest in rural areas of Manchuria. CCP troops and organizers had already infiltrated parts of the region and had taken possession of arms surrendered by the Japanese. Chou could have refused to allow the Nationalists to move, thus jeopardizing the overall cease-fire agreement. Surprisingly, he gave in. In the case of Manchuria, the CCP agreed to create an exception to the general rule of nonmovement that prevailed throughout the rest of China. Pursuant to the “Manchuria exception,” the Nationalists would be permitted to move their forces into and within the region to establish sovereignty and prevent a vacuum as the Soviets withdrew. CCP troops already situated in the three provinces comprising Manchuria would not move. They would stay where they were, mainly in the rural areas. For the Communists it was a remarkable compromise.

The details of the truce were falling into place. The plan was to announce its signing on January 10 so that it would coincide with the long-anticipated opening of the PCC, the body of thirty-eight delegates representing all of China’s political parties who were poised to begin hashing out the terms of unification. However, on January 9, the cease-fire negotiations conducted by the Committee of Three—Chou, General Chang Chung (representing Chiang), and Marshall as the mediator—ground to a halt. They had reached an impasse over the issue of Nationalist troop movements into two towns situated athwart rail junctions north and northeast of Beijing in what were then Jehol and Chahar Provinces. The towns, which offered a route into Manchuria from Yenan, were held by the CCP. “It would be a tragedy,” pronounced Marshall, “to have this conference fail at the last moment.”43 For Marshall and the prospect of a unified China, it was a critical moment. Unless the cease-fire agreement was signed, the PCC would almost certainly collapse. With neither side giving ground, the meeting adjourned.

Late that evening, the night before the PCC was to meet for the first time, Marshall went alone to Chiang’s residence. Arguing that Chiang had little to lose and everything to gain by postponing negotiations over the issue of troop movements into the two towns until a later date, Marshall prevailed upon him to concede. Marshall “suggested and [the] Generalissimo agreed” to announce the cease-fire agreement at the opening of the PCC meeting the next morning.44

The cease-fire announcement electrified the PCC delegates. Chiang’s opening address to their convention added to the momentum and raised expectations. To the dismay of the conservative wing of the KMT, Chiang advocated that the new unified China should adopt Western democratic principles, including freedom of speech and assembly, popular elections, equal status for all political parties, and release of political prisoners. Most Communists were euphoric. Their party newspaper, the Liberation Daily, proclaimed that the “rejoicing with which the Chinese people” received the cease-fire announcement “marks the beginning of peaceful development, peaceful reform, and peaceful reconstruction unique in the modern history of China.”45

To supervise the terms of the truce, Marshall directed that an Executive Headquarters be set up at Peking Union Medical College. Walter Robertson was appointed high commissioner and Colonel Byroade his chief of staff. Two other commissioners were appointed, one Nationalist and the other Communist. A cohort of 125 U.S. officers and 350 men, equipped with jeeps, trucks, planes, and radios, was assigned to conduct inspections and write up reports. As Byroade and the others began arriving at the college, the CCP was already accusing the KMT of cease-fire violations, and vice versa. “It appears that both sides are greatly exaggerating their claims,” wrote Byroade to Marshall. “Our teams will strive to obtain factual evidence to disprove claims if they are false.”46 Within days the truce machinery was in high gear. “The fighting did stop,” recalled Byroade. “A lot of sieges were lifted. It looked like progress was being made, and then both sides, but particularly the Communist side, started violating the agreement.” Byroade believed there would never be peace until the CCP army was integrated into Chiang’s Nationalist army.47

Marshall regarded the truce violations as inconsequential. On February 4 he reported to Truman that the PCC was “doing their job well,” and likened their deliberations to an American-style “Constitutional Convention.” With evident pride he told the president that even though he had no official role, he provided the PCC with the details of a draft “interim constitution” and that the PCC incorporated his draft into its plan for a “democratic coalition government.”48 Chiang did not share Marshall’s optimism. Privately, he confided to his diary that Marshall was naïve, that he was being taken in by the Communists and did not understand their deceptive nature.49

Even if Chiang was right, Marshall had reason to continue to pursue his mission with optimism. Thus far, he had already brokered a cease-fire. Unofficially, he had helped the PCC set the stage for a national assembly and a coalition government. Wedemeyer, Byroade, Melby, and many others had doubted these goals could be achieved. The third piece of his mission—integration and reorganization of the two armies—would be the most difficult. It was also the most important. Without true integration of the two armies, the political and economic basis for a coalition government could not be sustained.

By early February Marshall and his staff had drafted a plan for a “complete reorganization of Chinese military forces” and received authority from the Nationalists to discuss it with Chou En-lai.50 Explaining his plan to Chou, Marshall made it abundantly clear that commanders in the reorganized army must have no position in the civil government, a change fundamentally at odds with Chinese custom and practice. A few days later Chou reported that he and General Chang (on behalf of the Nationalists) had agreed that eventually the two armies would be reorganized and integrated into a total of sixty divisions—fifty KMT and ten CCP. Under the plan, a total of some 250 KMT and CCP divisions would have to be demobilized. That evening Marshall reported to Truman that “prospects are favorable for a solution to this most difficult of all problems.”51

After a series of marathon sessions, Marshall, Chou, and Chang concluded and signed an agreement to reorganize and integrate the CCP forces into the Nationalist army over an eighteen-month period. For the first time the two armies were to be combined under the control of a single government, not a political party. KMT troops would outnumber those of the CCP five to one. Even more notably, the Communists agreed to reduce their forces in Manchuria to a fraction of what they had been when Marshall first introduced his integration proposal. The meetings were surprisingly devoid of rancor. With humor and affection, Chou and Chiang began referring to Marshall as “the Professor.” Since Marshall as special U.S. envoy was not a party to the agreement, he expressed reluctance to be a signator. Both sides pressed him to sign as “Advisor.” Marshall gave in, saying, “If we are going to be hung, I will hang with you.”52

To the waiting press correspondents, General Chang and Chou En-lai proclaimed an end to eighteen years of hostilities and a new era of peaceful reconstruction of China. They heaped praise on Marshall, the “midwife” of unification. Marshall concluded the proceedings with a speech consisting of two sentences, the first aspirational, the second a warning. “This agreement . . . represents the great hope of China. I can only trust that its pages will not be soiled by a small group of irreconcilables who for a selfish purpose would defeat the Chinese people in their overwhelming desire for peace and prosperity.”53 To Marshall, the “irreconcilables” referred to the right wing of the KMT, members of a clique headed by the influential brothers Chen Li-fu and Chen Kuo-fu, who were implacably opposed to unification with the Communists.

While Marshall anticipated a threat from the right, he was not yet aware of an even larger threat from the left. Twelve days earlier, Mao had advised his politburo in Yenan that “the United States and Chiang Kai-shek intend to eliminate us by way of nationwide military unification . . . In principle, we have to advocate national military unification; but, how we shall go about it should be decided according to the circumstances of the time.”54 To put it another way, Mao was reserving judgment on whether the CCP would actually comply with the letter of the military integration agreement. As far as he was concerned, it was a scrap of paper that could be ignored at any time.

A few days after the military integration agreement was signed, the Committee of Three—Marshall, Chou En-lai, and General Chang Chi-Chung (who replaced General Chang Chun)—departed on a 3,500-mile tour of more than a dozen cities and towns, mainly in “troubled areas” in northern China, to explain the terms of the cease-fire and integration agreements to the principal army commanders on both sides and at the same time demonstrate by their presence the “appearance of cooperation” that the three of them represented.55 Marshall was treated as a conquering hero, signs in towns and cities calling him “Most Fairly Friend of China” and “First Lord of the Warlords.” At some point during the journey Chou left his personal notebook on Marshall’s C-54. Instead of having it examined or photocopied, Marshall turned it over to Chou unread and intact, thus earning a measure of trust that Chou could hardly forget. The notebook contained information identifying CCP’s secret agents, one of whom was a mole embedded in the KMT.56

The stop to visit with Chairman Mao at CCP headquarters in Yenan was the highlight of the trip. Yenan lies on the arid Loess Plateau in northwest China almost 500 miles south of the Great Wall, its highly friable and fertile “loess” soil deposited on the plateau by windstorms over the centuries. Mao and his CCP followers lived and worked there in hundreds of tiered one- or two-room caves carved into the sides of steep hills and valleys.

When the Committee of Three landed, thousands of Chinese citizens stormed the rocky airstrip in hopes of catching a glimpse of the world-renowned General Marshall. Round-faced Mao, dressed in blue peasant clothes with a China Red Army cap over his shaggy black hair, greeted Marshall and the others. In contrast to what he had told his politburo, the fifty-three-year-old Chairman “assured” Marshall during their first meeting that “the Chinese Communist Party would abide wholeheartedly by the terms” of the army integration and cease-fire agreements and the resolutions of the PCC. Though Marshall later told Truman he spoke frankly to Mao, in fact he was too diplomatic. During their talks Marshall began by telling Mao that he was “embarrassed” by a CCP press statement “to the effect that Manchuria was not within the scope” of the cease-fire agreement. As Mao knew, the Nationalists’ right to establish sovereignty in Manchuria was clearly covered by that agreement. The CCP statement was a deliberate fabrication. Instead of putting Mao on the spot by insisting that he come up with an explanation or denial, Marshall said that he did not wish him to respond.57 In retrospect, it was probably a mistake to allow Mao to save face. This was the time for Marshall to make clear that he would hold the Chairman responsible for mischaracterizing or otherwise trying to undermine the agreements. Marshall ended the day being entertained by folk dancers and skits in an “icy auditorium” and watching a film with Mao while lying beneath thick rugs to ward off the cold.58

Marshall wasn’t sure what to make of Chairman Mao. As he confessed later, Mao “remained a mystery.”59 Nevertheless, in his overly optimistic trip report to Truman, Marshall claimed that all “difficulties” were “straightened out” and that Mao as well as his field commanders pledged complete “cooperation.” His reception “everywhere was enthusiastic and in cities tumultuous.”60 This was an opportune time, Marshall wrote, to return to Washington. It was necessary to persuade Congress and various federal agencies to extend financial and other assistance to the KMT and the CCP, provided substantial progress was made toward the formation of a coalition government and an integrated army. Truman responded, ordering him home for consultation. He added that Winston Churchill was in the U.S. and “desires to see you.”61 Accompanied by Truman, the former wartime prime minister had just delivered his “iron curtain” speech at Westminister College in Fulton, Missouri, the same day Marshall met face-to-face with Chairman Mao in Yenan. Most of Churchill’s speech focused on the “front of the iron curtain which lies across Europe.” But, in an often overlooked line, Churchill warned that “[t]he outlook is also anxious in the Far East and especially in Manchuria.”62 No wonder he wanted to speak with Marshall.

The outlook in Manchuria was beyond anxious. It was dire. While Marshall was flying to Washington, the first large-scale cease-fire violation took place in and around Mukden, the old Manchu capital and the largest city in Manchuria. Marshall had firsthand knowledge of the terrain in and around Mukden, having inspected it on horseback in 1914.63 After looting Mukden of everything of conceivable value right down to the light switches, the Red Army, without any notice to the Nationalists, finally withdrew. Fifty thousand CCP troops led by General Lin Bao began to move in right behind them, planning to occupy and govern the city. However, the Nationalist New First Army, under General Sun Liren, a VMI graduate, raced up the rail line from the port of Ching Wang Tao to block their entry. In fierce street fighting Sun and his forces drove the Communists ten miles out of the city. The Nationalists entered Mukden on March 13. Under the “Manchuria exception” explicitly set forth in the cease-fire agreement, they were entitled to establish sovereignty. But CCP troops remained in the area and could counterattack at any time. Due to a marked shift in Soviet policy away from a peace settlement in China and in favor of supporting the CCP, Mao had no intention of honoring the Manchuria exception. Soviet policy had changed because Stalin felt threatened by Marshall’s initial success, worried not only about too much American influence near his border in Manchuria but also the political survival of the CCP. As a consequence, Mao and his party leaders decided in late March to “use maximum strength to control” key cities in Manchuria.64

When Marshall landed in Washington he knew that fighting could break out again in Manchuria. At his first press conference his optimism was muted. “I am not quite as certain,” he said, whether the Chinese political leaders understand the “vital importance” to peace in the Pacific of “their efforts toward unity and economic stability.”65 Concerned that the cease-fire agreement could disintegrate, Marshall radioed General Alvan Gillem, who was substituting for him in China while he was away. Marshall urged Gillem to travel to Mukden as quickly as possible to stop the fighting and the struggle for favorable position. “Further delay may be fatal,” he said.66

Relying on Gillem to hold things together until he returned, Marshall characterized the next four weeks as “the busiest, most closely engaged period of [his] experience, not even excepting wartime.”67 With his insider’s knowledge of the people and agencies that run Washington and the assistance of Dean Acheson, Marshall managed to cobble together an impressive aid package under the assumption that a coalition government would be formed. Among other items, he secured a commitment from the Export-Import Bank to extend a credit for $500 million (roughly $6 billion in today’s dollars), a new lend-lease program to be funded by Congress, $30 million in cotton credits, and the transfer of surplus coastal vessels and other such properties to China. “All in all,” he wrote Wedemeyer, “I think I have sold China.”68

Marshall thought he would have to “sell” Katherine on returning with him to China. In a letter to Frank McCarthy he confided that he “hope[d] to bring Mrs. M. back with me for the remaining months of my stay—until about August or September.”69 Research reveals, however, that Madame Chiang, probably at Marshall’s suggestion, began a campaign in February to convince Katherine to join her husband in China. Katherine recalled that Mayling sent her two letters claiming that she, Madame Chiang, “made” George “promise he’d bring me back with him.”70 A surviving letter that Katherine sent to McCarthy on February 19, 1946, confirms her memory. In that missive she wrote that “a letter from Mm Chiang came this A.M. asking me to come over. She says George needs me in the wonderful work he is doing for her country.”71 Whether it was Mayling’s or George’s idea, by the time Marshall landed in Washington Katherine was sold on going to China. She spent at least a week out at Leesburg, packing and getting “all those injections” from doctors to ward off diseases she might be exposed to in the Far East.

One weekend afternoon while George was relaxing at Dodona, Katherine handed him a typed manuscript and asked him to read it while she took a walk. She had just finished the last chapter of a memoir about their life together that she had been secretly writing for months. Katherine walked for what seemed to her like hours. When she returned George was still reading. Eventually, he laid it down and said, “Well, I think it’s time for us to go to bed.” So they went upstairs. “He didn’t say a word—not a word,” she recalled. In the breakfast room the next morning, she asked him what he thought of the manuscript and whether it should be sent to the publisher. He replied, “If you feel that way about me, yes, but on condition that you don’t sell it on my name.”72 With a few revisions by Marshall, the memoir, titled Together: Annals of an Army Wife, was published later that year by Katherine’s brother, Tristram Tupper. It became a Book of the Month Club selection and a best seller.

Since the cease-fire, particularly in Manchuria, was crumbling, Marshall was pressured to return to China sooner than planned. On April 2, Madame Chiang wrote, “I hate to say ‘I told you so’ but even the short time you have been absent proves what I have repeatedly said to you—that China needs you.”73 Apparently, Madame had begged Marshall not to leave China in the first place. A few days later, a radio message to Marshall from Walter Robertson was more emphatic. “[T]he situation is so serious and is deteriorating so rapidly that your immediate return to China is necessary.”74

Despite the urgency, George and Katherine did not leave Washington until April 12, and their flight back to China was leisurely. They arrived in Chungking on April 18, almost six weeks after Marshall had left. While they were in the air, Soviet general Fedor Karlov notified detachments of the Communists’ Eighth Route Army that he and his Red Army troops intended to withdraw from Changchun, a city of 750,000 that had been the capital of Manchukuo, the Japanese puppet state that included all of Manchuria and Inner Mongolia. Changchun was almost 300 miles north of Mukden on the main railway that ran up through the middle of Manchuria to Harbin, the northernmost big city. At the time, the Nationalists had 4,000 poorly equipped regular army troops in Changchun, plus a few thousand local conscripts and Japanese soldiers. As General Karlov boarded his special train for Harbin and the remainder of his Soviet forces were still departing the city, 20,000 CCP troops, armed with Japanese weapons, captured the surrounding airfields and attacked the Nationalist forces. American correspondents who were there reported that gunfire was constant for three days and nights. The fighting in the streets was savage and casualties were heavy. On the fourth day, what was left of the Nationalist garrison set up a defensive perimeter with sandbags and barbed wire around the five-story Central Bank Building and put up “an Alamo-type defense.” Outgunned and outnumbered, they were forced to surrender or be wiped out. It ended when Japanese (and possibly Soviet) artillery and tanks manned by the Communists turned the bank building into what Henry Lieberman of The New York Times called an “inferno” and the Nationalist commander fell wounded after rushing into the plaza from the burning bank.75

The capture of Changchun, coming as it did on the day Marshall returned to Chungking, was by far the most significant military success by the CCP against Chiang’s Nationalists. The State Department’s white paper on the fall of China, published in 1949, called it a “flagrant violation of the cease-fire agreement which was to have serious consequences.” For two reasons, it may have doomed Marshall’s mission. First, the Changchun conquest instilled confidence in Mao and his generals in Manchuria that they could eventually defeat the Nationalists on the battlefield, thus making them “less amenable to compromise.” And second, “it greatly strengthened the hand of the ultra-reactionary groups” in the KMT government, providing them with solid reasons for claiming that the CCP “never intended to carry out” the agreements leading to unification.76

“The dust heat s[t]ench are beyond description,” wrote Katherine.77 Her mood during her first week living in Chungking matched the grave situation that confronted her husband. As it turned out, the Nationalists had also violated the truce agreement, which provided the Communists with a handful of convenient excuses to justify their bold attack on the city of Changchun. Though each side, therefore, shared blame, Marshall’s initial approach as a mediator was to fault the Generalissimo’s “advisors” for gifting the Communists with credible accusations that the Nationalists were the first of the two sides to breach the cease-fire.78 His objective was to move the Nationalists toward restoring the truce. Chiang resisted, vowing to continue fighting until his KMT troops recaptured Changchun and controlled the rest of Manchuria. With Chairman Mao’s blessing, Chou, on behalf of the CCP, was willing to enter into another cease-fire pact, provided the Communists occupied Changchun while the agreement was being negotiated. Marshall met day and night separately with each side. By April 29, Chiang offered the Communists what Marshall characterized as a “great concession.” If the CCP agreed to evacuate Changchun, Chiang was willing to establish a cease-fire line north of the city, suggesting that the Communists might be left with de facto control of all of northern Manchuria. Casting blame on the Communists for their attack on Changchun, Marshall talked tough to Chou. He implored him to accept Chiang’s proposal, saying he “had exhausted his means.” If the CCP would not go along with Chiang’s offer, Marshall implied that his mediation efforts were over. “Moved by Marshall’s efforts,” Chou said he would wire Yenan “in hope for an early reply.”79

Chou may have been moved, but his boss, Mao, would not budge. His generals believed they were in a strong strategic position in Manchuria. The Soviets had just turned Harbin over to the CCP. The Red Army formally withdrew from Manchuria and pulled back into the Soviet Union. The Communists were not about to give up Changchun without a fight, or so they said at that time. Marshall was discouraged. On May 6, he wrote Truman that he was at an “impasse” and that “[t]he outlook is not promising.” In Marshall’s view, there was so much distrust and fear that each side preferred to take its chances on using force rather than pursuing a genuine coalition government through peaceful negotiations. Nevertheless, he told the president that he would keep trying “to resolve the difficulties . . . in a manner that will keep the skirts of the U.S. Government clear and leave charges of errors of judgement to my account.”80

At the beginning of May, Chiang moved his government down the Yangtze to the old capital in Nanking. Katherine was “glad to have seen Chungking but once is enough.” The Marshalls were billeted in a fine house and grounds on Ning Hai Road that had formerly belonged to the German ambassador. The place was large enough to accommodate offices, the mission staff, and a large conference/recreation room, where movies were shown in the evenings. Katherine and George lived in a wing on the second floor with two bedrooms and a porch overlooking the garden and lawn. Katherine wrote that their quarters “had an electric fan which is a godsend here for the heavy dark curtains must stay drawn all day—to keep out heat & dust.”81 John Hart Caughey, who lived in another upstairs room, wrote his wife that although servants wait on Mrs. Marshall “hand and foot,” she is “none too happy” because she doesn’t have much to do and says she “feels like a kept woman. The general makes a big point of it because he thinks it is so funny.”82

On May 9, a beautiful spring day, Dwight Eisenhower, who succeeded Marshall as chief of staff, arrived at the Marshalls’ new home. He was on a lengthy inspection tour of army installations in the Far East. Ostensibly, he stopped in Nanking to assess the readiness of troops still stationed in the area. His real mission, however, was to deliver a top secret message to Marshall from the president. After lunch with Madame and the Generalissimo, the two old friends retired to the privacy of Marshall’s office. Eisenhower explained that Secretary of State Byrnes would be resigning due to “stomach trouble.”83 (In fact, Truman had long been disenchanted with Byrnes because he was too cozy with the Soviets and failed to show proper deference to the presidency.) The president wanted to know if Marshall would take the job. Years later, Eisenhower recalled Marshall’s response: “Great goodness, Eisenhower, I would take any job in the world to get out of this place. I’d even enlist in the Army.”84 Marshall’s serious answer was a conditional yes. He would accept the position if offered, but he could not leave China until September, by which time he hoped that the parties would agree to a new truce and a path toward unification. Upon his return to the U.S., Eisenhower explained Marshall’s position to the president. In a letter to Marshall dated May 28, Eisenhower wrote that Truman “expressed great satisfaction, saying ‘This gives me a wonderful ace in the hole because I have been terribly worried.’”85

Since informing the president that his efforts to restore the cease-fire were at an “impasse,” Marshall spent the rest of the month talking with each side separately. However, both were beginning to privately question his judgment and impartiality. The Nationalists held Marshall responsible for persuading them to trust the CCP, which in their view led to the loss of Changchun. Chou and the CCP were critical of Marshall for previously allowing U.S. naval vessels and American flag shipping to transport Nationalist troops and supplies to ports in North China.

Meanwhile, developments in the field trumped negotiation. On May 19, American-trained Nationalist divisions, under the command of General Du Yuming, having moved north from Mukden along the railroad route, inflicted what some said was a decisive defeat on General Lin Bao’s Communist armies in the Second Battle of Siping. The battle lasted for more than a month. Lin’s troops suffered heavy casualties and desertions while trying to defend the small railway city. However, his main force, though battered and weakened, managed to withdraw from Siping and limp to the north. For the Communists, the defeat at Siping was a turning point because it forced them to temporarily abandon conventional tactics and return to a strategy of guerrilla and smaller-scale mobile warfare while they recruited, trained, and strengthened their armies. With Mao’s approval, Lin elected not to try to defend Changchun and he continued his withdrawal north through Changchun all the way to the Sungari River, only sixty miles south of Harbin. Du’s Nationalist troops, wearing American-style uniforms and carrying U.S.-made rifles, marched unopposed through the gates of Changchun on May 24.

Well aware that the Nationalists had recaptured Changchun, Marshall wired Chiang that his advances into Manchuria were making Marshall’s efforts to broker a cease-fire “increasingly difficult” and compromising his “integrity.”86 By that time Chiang was already weighing the pros and cons of a cease-fire. The closer his troops got to the border of the Soviet Union, the greater his concern that the Soviets would intervene on the side of the CCP. Marshall was also worried about how the Soviets would react. In light of the difficulties the Truman administration was having with Stalin in Europe he could not afford to get mixed up in a confrontation with Soviet forces in Asia.

Chiang met with Marshall on the morning of June 4. Curiously, there are no minutes or other contemporaneous records of this critical “three hour conference” that Marshall referred to in his letter to Truman.87 Precisely what was said, or what threats were made or not made during this long meeting, will never be known. What is known for sure is that by the end, Chiang agreed to a cease-fire in Manchuria, a decision that he told Marshall was “his final effort at doing business with the Communists” and later called “a most grievous mistake.”88 Looking back through fogged glasses, Chiang claimed years later that he frittered away the best chance the Nationalists would ever have to defeat the Communists on the battlefield.89

At noon on June 6, the Generalissimo and the CCP issued orders to their respective generals for a fifteen-day truce (later extended to the end of June) to end the fighting in Manchuria, during which the parties were to reach agreements on the details for a permanent cease-fire and implementation of the previous agreement of February 25 for the reorganization and integration of the two armies. With a show of optimism, Marshall wrote Colonel Marshall Carter, who was the liaison between the Pentagon and the State Department, that he was faced with “a hell of a problem but we will lick it yet, pessimists to the contrary notwithstanding.”90 The shaky cease-fire held, aided by the fact that Colonel Byroade dispatched eight truce teams to Manchuria and North China, but as June drew to a close Nationalist generals were preparing to attack CCP forces for violating the truce. On the 30th, with the extended cease-fire in Manchuria about to expire, Marshall met with the Generalissimo. According to John Robinson Beal, an American adviser to the KMT, Marshall argued that if Chiang’s military leaders were to break the truce and attack, they would be “decreeing war against the will of the people,” similar to what happened in Japan. “[A]nd look at Japan today,” Marshall reportedly said to Chiang. Since the Generalissimo regarded himself as the George Washington of China, the savior of his people, he “quoted the Bible” and “almost wept” in response. Marshall told Beal that his argument had a “tremendous effect” on Chiang, and it did.91 By the end of the five-hour session, the Generalissimo made up his mind. He did not want to end the truce with an attack on Lin Bao’s main forces in Manchuria. He ordered that no “aggressive offensive action” should be taken by Nationalist generals and their forces.92

From June through October, there was almost no fighting in Manchuria, yet in the south limited offensives and counteroffensives were launched by both sides. While Chiang seemed confident that his troops were pushing back the People’s Liberation Army—the new name for Mao’s armed forces—Marshall was worried that the sporadic fighting would lead to all-out civil war. He tried to find a solution, but his meetings with Chiang and Chou were, in his words, “unproductive.”93 In mid-July the Generalissimo and Madame, with Katherine as their guest, left for Kuling, their summer residence high in the mountains 250 miles southwest of Nanking. “Marshall was plainly annoyed,” wrote Beal in his diary. Chiang’s “departure stopped the negotiations cold,” and Marshall interpreted it as an effort “to force the Communists into coming to terms.”94

Shortly before Chiang and his entourage departed for Kuling, Dr. John Leighton Stuart, the newly confirmed U.S. ambassador to China, arrived on the scene to assist Marshall, who realized he was in desperate need of political expertise. Except for Stuart’s age—he was seventy—he appeared to be the ideal choice. Stuart was born in China, son of missionaries, but educated in America, where he was ordained as a Presbyterian minister. He spent most of his adult life in China, serving for years as president of the prestigious church-affiliated Yenching University near Beijing. Stuart knew almost all of the Chinese political leaders. As one of the most highly respected foreigners living in China, he was liked and trusted by the liberal, conservative, and moderate wings of the CCP, the KMT, and other political parties. Marshall believed Stuart could help him “raise the present negotiations from the level of military disputes to the higher political level for securing a genuine start towards a democratic government.”95

Though Chiang had decided to spend the summer up at Kuling, Marshall could not afford to allow his mission of unification to stall. Thus, he had little choice but to journey by plane, boat, and jeep to the base of Lushan Mountain, where he would be carried by “coolies” in a sedan chair over six miles of trails to the top of the mountain. Each weekend from July 18 until the last week of September, the general, frequently accompanied by Stuart, would make the trip, patiently meeting for hours with Chiang and his aides in an effort to continue negotiations toward peace and a coalition government. It was not all business. During his visits to China’s summer capital, where the air was fresh and cool, he would spend private time with Katherine in her European-style stone cottage that overlooked a swimming pool and the mountains beyond.

Despite their efforts, Marshall and Stuart made little if any progress during the exhausting summer of 1946. The Nationalists, whose armies seemed to be winning battles for towns in the south, insisted on extracting political concessions from the CCP before they would agree to another truce. The Communists, who were rebuilding in the north, demanded a cease-fire before they would enter into serious political negotiations with the KMT. “For the moment,” wrote Marshall to Truman, “Dr. Stuart and I are stymied.”96

By the time the Generalissimo was carried down from the mountain in late September Stuart and Marshall were not only “stymied.” In Marshall’s words, Chiang had made “stooges” of them.97 That remark was triggered right after the KMT Central News Agency announced on September 30 that Nationalist forces had begun a three-pronged offensive to capture Kalgan, the largest and most important city in the hands of the Communists south of the Great Wall. Marshall was thoroughly fed up, convinced that Chiang was using negotiations as cover while his Nationalist forces moved on Kalgan, blocking the Communists’ gateway to Manchuria. The next day Marshall threatened Chiang with an ultimatum, telling him that he was going to recommend to Truman that his mission be terminated.98 Though Marshall was probably bluffing, Chiang could not risk losing face (and vital support) by having the U.S. president shut down Marshall’s mission. He hurriedly summoned Stuart and told him that he was amenable to halting his advance on Kalgan and agreed to a short truce.

The details of Chiang’s standstill and ten-day cease-fire offer were sent to Chou, who was in Shanghai. It was proposed that during the truce a group under Stuart would establish a formula to determine the number of CCP delegates allowed to participate in the National Assembly for formation of a coalition government and that Marshall’s Committee of Three would implement the February agreement to reorganize and integrate the two armies. For a few hours Marshall and Stuart allowed themselves to dream that a deal might still be possible.

In Shanghai, Chou greeted the proposal with suspicion. He believed the latest cease-fire proposal was just another scam by Chiang to obtain a breathing spell while falsely professing a desire for peace. He rejected Chiang’s offer. The odds were against him, but Marshall was not ready to let hope die. Since Chou was unwilling to sit down with him in Nanking, Marshall cooked up a ruse with General Gillem, who was posted in Shanghai, to confront him there. Marshall phoned Gillem. “I’ve got to see Chou En-lai once more . . . gonna make one final move here [to] see if he won’t assist me in breaking this thing up.” Early on the morning of October 9, Marshall secretly flew to Shanghai and concealed himself behind a screen in the living room of Gillem’s house. Chou entered the house with Gillem, under the impression that he and Gillem were going to have a quiet lunch. When Marshall appeared from behind the screen, Chou was caught off guard and “damn near died,” recalled Gillem.99 Having ambushed Chou, Marshall immediately went to work, gambling that a face-to-face appeal, heightened by the element of surprise, might persuade Chou to agree to a truce and take steps leading to a coalition government.

As soon as Marshall gave Chou a chance to speak, he could tell that his gambit had failed. Chou did not mince words. He was outraged over the attack on Kalgan, claiming the Generalissimo was “driving headlong into a nation-wide split.” Chou said he would consider a truce only if it was permanent and only if the Nationalists moved their troops back to the positions they held in China proper and Manchuria when the earlier cease-fire agreements were signed. He impugned Marshall’s integrity, suggesting that Marshall and Stuart were helping Chiang “find time for moving troops and munitions” into place for a renewed attack on the Communists defending Kalgan.

This was too much for Marshall. He had spent weeks trying to persuade Chiang to stop the fighting and start the peace process. Barely concealing his anger, he responded to Chou with what must have been a chilling tone. “I told you some time ago that if the Communist Party felt that they could not trust my impartiality, they merely had to say so and I would withdraw. You have now said so.” He paused for effect. “I am leaving immediately for Nanking.”100

Despite the implication of his words, Marshall was still unwilling to let hope die. Rather than withdraw, he agreed to a plan hatched by Ambassador Stuart and two left-leaning political parties that succeeded in persuading Chou to return to Nanking without losing face.101 However, while Marshall planned to salvage negotiations leading to an end to the fighting, Chiang had different ideas. On the day after Marshall and Chou clashed at Gillem’s house, the Generalissimo addressed the nation. It was Chinese National Day, the anniversary of Sun Yat-sen’s 1911 revolution. Chiang announced that a national assembly would convene in a month to fashion a constitution and he would continue to seek a settlement through mediation with the CCP. His message of conciliation was drowned out by news that Kalgan fell that day to the Nationalists. The Communists lost roughly 100,000 men. Those who survived retreated into the northern provinces. CCP forces in Yenan were cut off from Manchuria. Fifteen days later, Chiang ordered his troops to attack the city of Antung on the Chinese side of the Yalu River border with Korea. It was obvious that Chiang’s strategy was to use force rather than compromise to compel Chou to return to the bargaining table.

After capturing Antung, the first major city in Manchuria to fall to the Nationalists since the June cease-fire agreement, Chiang announced that it was time for another truce. In his diary John Melby wrote that Marshall told him, “I can’t go through it again. I am just too old and too tired for that.”102 Marshall may have said what he felt at the moment, but the stakes were too high to throw in the towel. Once again he spent hours meeting with Chiang, trying to shape cease-fire terms that might be acceptable to the CCP. Asked by Marshall to discuss terms in a meeting of the Committee of Three, Chou replied, “I will make another try.”103 Notwithstanding Marshall’s efforts, it soon became apparent that there would be no agreement. Chou made a seemingly reasonable request. He asked that Chiang postpone the convening of the National Assembly until decisions were made via negotiation as to how many Communists would be allowed to become voting members of the assembly and thus have a voice in formulating the new constitution. Chiang agreed to a three-day postponement, but the delay yielded nothing. The National Assembly convened on November 15 even though not a single Communist had been selected as a delegate. The plan for a cease-fire collapsed.

The next day, Chou told Marshall that Chiang and the KMT had “sealed the door of negotiations.” Accordingly, he was going to return to Yenan to confer with Mao and “analyze the overall situation.” Chou assured Marshall that he still had “high respect for [him] personally,” but “the Chinese problem was too complicated and the changes are tremendous.” Before they departed, Marshall asked Chou to determine whether the authorities in Yenan wanted him to continue in his “present position” and to provide him with an honest answer without regard to whether he might lose face.104 Knowing the Chinese Communists, he doubted he would get a straight answer. As they said their goodbyes Marshall wasn’t sure he would ever see Chou again.