While the development and continuous improvement of the rifle is of great importance to the hunter, the development of modern sporting optics – the binocular, the spotting scope, and the riflescope – are of equal importance. Without the benefits offered by modern optics, the practice of hunting would still be quite primitive; it would be far more dangerous, more animals would be wounded, and game management would be nearly impossible without the aid of optics in population assessment surveys. Therefore it is of great importance that every hunter give careful thought and consideration to the proper selection and use of sporting optics. The subjects of this book also speak volumes of the need for quality optics. Success rates for selectively hunting, and the field judging of a mature animal rise exponentially when using quality optics.

The idea for the first telescope dates back to nearly 1600. Hans Lippershey, an eyeglass lens manufacturer in Holland, discovered that holding two lenses, one in front of the other away from the eye, produced a larger image of a distant object. From Lippershey’s discovery came what was to be the telescope, the basis of all sporting optics.

The development of the first binocular was nearly simultaneous to the development of the telescope. Lippershey applied for a patent for a “binocular instrument” in 1608. Being a designer of eyeglasses, he realized the benefits of using both eyes rather than only one to view a distant object through a magnifying lens system. However, as there was no way either to focus the image or align the two halves so that they produced a single image, the headaches caused to the first users must have been terrible. Also, the only way at that time to make the magnification level higher was to make the instrument larger, making the early binoculars too large and heavy for any practical use. The invention was put aside for almost 250 years until someone improved upon its design.

That someone was Ignatio Porro, who in 1854 invented a design for an optical system that used prisms to overcome the problem of making a higher magnification instrument small enough to be practical and allow it to be focused. The modern porro prism binocular (as Porro’s design became known) is very similar to Porro’s original idea, although refinement of materials, lens production, and manufacturing techniques have brought it to a level that would have amazed him.

Naturally, the development of the improvements in telescopes eventually led to the development of the riflescope. While it is true that simple riflescopes predate the Civil War, the earliest design of the modern riflescope was created in Europe shortly after 1900. Still crude by today’s standards, these scopes were difficult to make and very expensive. Consequently, most hunters could not afford them. Hence, these first examples of the modern scope had little influence on the practice of hunting; most hunters still continued to use conventional sights. However this would soon change.

By the early 1930s, less costly riflescopes became available in the U.S. These new scopes used adjustable mount systems and limited internal reticle adjustments. Yet there remained considerable widespread doubt that riflescopes were actually necessary for hunting. They were not waterproof, were prone to fogging, and the early internal adjustments were often unreliable. Overcoming these problems was key if a truly useful riflescope was ever to be produced.

Marcus Leupold, the son of Fred Leupold, the founder of Leupold & Stevens, and an avid hunter, was determined to create a riflescope that was waterproof and resistant to fogging. Immediately following World War II, Marcus began developing one of the first riflescopes deemed to be accurate, reliable, and waterproof. His pioneering attitude and far-sighted thinking removed all doubts about the usefulness of riflescopes. Leupold’s advances in riflescope design created a cultural change among sportsmen. Today, it is indeed rare to find someone who does not recognize the advantages of the telescopic sight over conventional iron sights.

The use of modern sports optics provides a number of benefits, for the user, for other hunters, for the animal, and for the practice of hunting itself. For the user, the binocular and spotting scope offer better discrimination of the size, sex, and condition of the animal, while the riflescope offers the benefit of a more accurate target picture and, thus better shot placement. Better selection and shot placement reduce the number of mistakenly shot, as well as of wounded, animals, which in turn benefits game management and the image of hunters. Limitations on eyesight are reduced or eliminated, as is eye strain as the eye no longer must change its focus repeatedly while viewing the target. A more accurate sight picture is a benefit to other hunters in the field as it reduces the possibility of mistaken identity and the sometimes tragic consequences of it.

Thus with all these advantages, it is easy to see how the riflescope has changed hunting as we know it today. However, it is surprising to discover just how little many hunters know about optics. Great care is often taken in the selection of a firearm, including customizations for individual fit and shooting style. Equal care is taken with ammunition selection, whether store bought or hand loaded. Yet many hunters do not make the same effort in the assessment and selection of their optics. Quite often, this is not from inattention; it simply comes from the belief that the subject of optics is too complex to learn. The following pages will prove that impression to be incorrect, and will allow a hunter to bring just as much insight and understanding to the selection of a riflescope as is brought to the selection of all other hunting equipment.

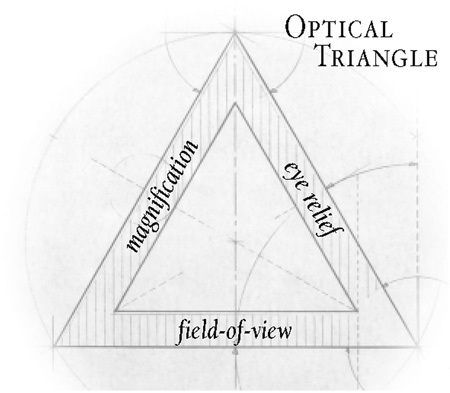

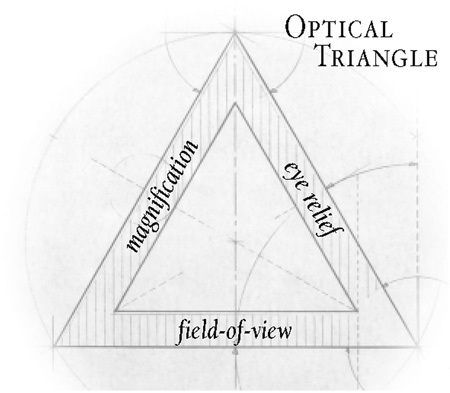

All optical devices rely on their optical system. Optical system design is limited by the laws of physics. To make a superior optical instrument, optical engineers must take advantage of every possible advance in materials and combine them together in such a way that they push the limits of these laws. To do this, they must create an optical system that balances three crucial features – magnification, field of view, and eye relief – within the Optical Triangle

In the Optical Triangle, each side represents the limits of one of the three features common to all optical systems – magnification, field of view, and eye relief. Magnification is, of course, how much the optic magnifies the object. Field of view is simply how much area is shown to the user in the image, typically measured by how many feet are visible from one edge of the image to the other at a distance of 100 yards. Eye relief is the distance measuring how far away from the eyepiece the user’s eye can be and still achieve a full sight picture. While these three features may not seem linked together, in truth, they are inseparable.

The space inside the triangle represents all the possible combinations of these three features. Every optical system design can be placed somewhere in this triangle by virtue of its amounts of magnification, field of view, and eye relief. If you begin in the center of the triangle and move closer to one side, you will see that you are moving away from another. As each side represents one feature, this means that as one feature increases, one feature decreases. Moving from one position to another within the triangle demonstrates how the elements of a scope’s design are a delicate balance between features.

The optical engineer must make the determination as to just where to strike a balance that will offer the best possible combination of features without making the optic difficult to use. For instance, if eye relief is sacrificed to get a better field of view, someone wearing eyeglasses may not be able to use the device. Trade-offs include safety considerations as well, especially in the case of eye relief in riflescopes.

Of the three critical factors in optical design described by the Optical Triangle, field of view is perhaps the most important to the hunter. A wide field of view allows an animal to be brought into view quickly. In the case of binoculars and spotting scopes, large areas can be scanned quickly to discover possible harvestable game. In riflescopes, field of view is a key factor in determining how quickly a the point of aim can be aligned on the target. A narrow field of view in a riflescope can place the hunter at a severe, or in the case of such dangerous game as bear or African buffalo, dangerous, disadvantage.

As the Optical Triangle clearly shows, changes in magnification level affect field of view. It is a general principle that the higher the magnification, the narrower the field of view. For example, assume that the field of view at 6x is 36 feet at 100 yards. If the animal viewed is 6 feet long, then at 6x you would divide the size of the object by the field of view (6÷36=.16 or about 1/6th), so the animal would fill 1/6th of the field of view at 100 yards. At 10x, for example, assume the field of view is 20 feet at 100 yards. For the same animal viewed at 10x, using the same equation (6÷20=.3 or about 1/3rd), would fill 1/3rd of the field of view. Clearly, if getting the animal into view quickly is important, a magnification level that causes the animal to fill less of the field of view will allow for easier and more rapid viewing.

The difference in field of view between magnification levels is why so many hunters choose variable magnification level riflescopes scopes such as 3.5-10x40mm or 4.5-14x40mm models that allow for lower magnification – wider field of view settings when needed. It is also why open plains hunters opt for higher magnification binoculars than those hunting in the forest. The key is to know the expectations of the terrain and conditions when choosing the right optics for the hunt.

That’s why it’s important to know when to use which optical tool in the field. Each has its own strengths and weaknesses. Binoculars with their 8x, 10x, and occasionally 12x magnification settings can be very useful in surveying areas or in assessing not-to-distant animals as possible targets. Spotting scopes are most often higher in magnification and as such are the best choice for long distance viewing. However, an important item to remember is that increased magnification magnifies not only the item you wish to view, it also magnifies everything else, such as moisture in the air, heat waves, smoke, etc. That’s why most hunters seldom use more magnification than 40 to 45x spotting scopes; higher magnification than this is rarely usable in the field because of atmospheric condition.

Then of course, there are riflescopes. Riflescopes are intended for aligning the point of aim on the target. It is never a good idea to scan the terrain with one as this could result in the rifle being pointed at another person. Variable magnification scopes are very useful for general purpose scopes as they allow for the scope to be set at a low magnification setting for target acquisition then adjusted up for fine shot placement. In the case of dangerous game where the action is fast and the distances close, fixed low magnification scopes with their extraordinarily large field of view are preferred.

One of the great ironies of modern binoculars, spotting scopes, and riflescopes is that despite all the new technological developments in materials, designs, and manufacturing techniques, a tiny amount of water, even water vapor, inside an instrument can render all these developments meaningless. Many people simply take it for granted that all scopes are waterproof these days. They’re not. Yet a scope or binocular fogging is one of the worst equipment malfunctions that can happen on a hunting trip; it is literally a “hunt stopper.” Marcus Leupold learned this firsthand – which is why his company, Leupold & Stevens, invented the first waterproof riflescope.

Some hunters think that they do not need to be concerned about waterproof products. They use their optics in places that they are not likely to fall into a river or get terribly wet. Even so, they should still be concerned as being waterproof can give a scope or binoculars other benefits as well, such as fog resistance.

Not all waterproof sports optics are resistant to fogging. To make them both waterproof and resistant to fogging, they must not only be capable of keeping water out, they must be filled with and retain nitrogen inside as well. If air is left inside the water vapor in that trapped air can condense into fog when the temperature changes. That’s why truly waterproof instruments are filled with nitrogen, which cannot form water molecules. However, this leaves the manufacturer with an additional challenge, not only keeping out the water and the air, but also keeping in the nitrogen.

For the best results, precision manufacturing and assembly is a necessity. All sports optics have some external joints, such as adjustment dials and eyepiece shells. The key is to keep the tolerances tight. A precisely designed, manufactured, and assembled joint fits closely and is easier to seal effectively. The final question that should always be asked is “Is the manufacturer willing to guarantee the product to be waterproof?”

Clearly, the development of modern sports optics has revolutionized the way hunting is practiced. The benefits of more successful harvests as well as increased safety and reduced animal wounding themselves justify their use. The decision then is to determine which one to use. Magnification is useful to determine animal selection, as well as discrimination of detail and precision shot placement, however it can be a hindrance if speed in sight alignment is hindered by the constriction of field of view that accompanies higher magnification levels.

The waterproof properties of a scope can indicate other crucial factors in the scope, such as its resistance to fogging and the retention of anti-fogging gasses such as nitrogen. Strong waterproof guarantees and testing also denote scopes with tight fitted joints that can only be the result of careful attention in manufacturing and assembly, which in turn often denote durability and hence reliability.

Careful consideration of these things when selecting sports optics will be of great benefit, as they can greatly increase the chances that the scope selected will give decades of good service and aid in successful harvests. Neglect of these factors can result in ill-chosen products that may likely fail in the field, resulting in missed or wounded animals, and lost opportunities. As such, good optics are worth ten times their price while poor ones are frightfully expensive and are never a bargain even if obtained for free. ■