A disembodied voice found its way through a wall of vegetation framed by laurel and swamp maples. “I can’t see anything!” Standing on the edge of Mooresfield Road, I shouted, “Come on out!” Brian Hokeness, my intern in the Summer of 1994, emerged from the thick underbrush. He was dripping with sweat and had scratches on his bare arms. Honeysuckle was grabbing at his ankles. “Watch out,” I cautioned, as I guided him toward the cleared shoulder of the road, away from the poison ivy poking through the narrow dirt-and-gravel apron that separated asphalt from wilderness.

If I believed in omens, I would conclude that we weren’t supposed to find the remains of Ruth Ellen Rose, or even South Kingstown Historical Cemetery #11, and let it go at that. But, having no history of supernatural experiences, and being some-what stubborn, I said, “I’ll try again in the Fall, when some of the brush has died and the visibility’s better. Clippers would be a big help.” It was hard to believe it had been twelve years since I discovered that the Rose family had a vampire problem, and I still hadn’t found the grave. I’d learned patience. So many trails I’ve followed have led to dense wilderness or, worse, dead ends.

I’m not the only one this has happened to. In February, 1975, Raymond McNally was in Rhode Island to address a University of Rhode Island honors colloquium on aging, dying and death. Three years before, McNally and Radu Florescu had coauthored In Search of Dracula, a description of their search for the historical Dracula, Vlad Tepes, after whom they claimed Bram Stoker modelled his fictional vampire. This connection is not universally accepted. In Dracula: Sense & Nonsense, Elizabeth Miller writes: “Count Dracula and Vlad the Impaler. Never has so much been written by so many about so little.” Then, in 1974, McNally wrote A Clutch of Vampires, a cursory treatment of a variety of vampire cases, including Mercy Brown, drawn from the Providence Journal account of 1892, and William Rose. While in South County, McNally and Providence Journal-Bulletin staff writer Fritz Koch went in search of the Rose family vampire, presumably interred about seven miles south of Mercy’s gravesite. Koch described their quest in the newspaper.

And in Peace Dale, William Rose disinterred the body of his daughter in 1874, cut out the heart and burned it to prevent further attacks from her grave on the living family members.…

A hired hand at a handsome old estate on Rose Hill Road said he knew where the Rose family burial ground was and, sure, he’d be glad to take us there himself. After he joined the expedition, he was politely informed that our “interest in local history” had to do with vampires. But, proving a bit of an occultist himself, he said he, too, had heard of the incident. He guided the party up Rose Hill Road several hundred yards to a cemetery, set off in the woods and surrounded by a chest-high stone wall. The sound of a gate latch snapping shut startled, but did not deter, the searchers.

“I’ve got it,” McNally cried suddenly, rushing forward to a large gray stone marked “William Rose” and pointing to engravings that indicated the man would have been just about the right age in 1874 to dig up his daughter’s grave.

A thorough search of the graveyard, however, failed to turn up the resting place of the daughter. The group beat a hasty retreat, delivering the professor to the University just in time to deliver his 4 p.m. lecture.

More than a month before we were thrashing about in the swamp maples, I had asked Brian to write to McNally in the hope that he could fill in some of the information hinted at in the Journal-Bulletin article. McNally included the following in his reply:

I know that William Rose dug up the body of his daughter in 1874 and burned the heart of the corpse, because he thought she was a vampire. I visited the Rose family graveyard; there I was told that rumor had it that William Rose was involved in Druid rituals. I was even shown what was purported to be an altar on which he performed sacrifices.

The mention of Druid rituals and altars triggered my memory—but it didn’t connect with William Rose. It was, rather, Joseph P. Hazard’s “Druidsdream” (built about 1850) and “Witches Altar” (built in the late 1800s). Obviously, this was a matter that begged for further investigation.

Brian and I began our ill-fated attempt to locate the grave of William Rose’s daughter in the cemetery book at the South Kingstown Town Hall. We noted the four cemeteries that seemed promising and set out with list and map, full of hope. We found no Roses, but I did spot the gravestone of William E. Peckham (1860–1884). After photographing the headstone, I told Brian that I had heard from students at the University of Rhode Island (located in the village of Kingston about two miles east of the cemetery), who said that Will Peckham’s ghost was seen wandering about the campus. Much of the land on which the university campus is built was part of the Oliver Watson Farm, not the Peckham Farm as the campus newspaper erroneously claimed. But Jeremiah G. Peckham (1826–1908, buried in the Peckham Lot; William’s father?), a banker and farmer, was one of the trio of South Kingstown figures who established, in 1888, what became the University of Rhode Island in 1892. According to the legend, William Peckham killed his wife, Nancy, because he thought that she was being unfaithful. He was found guilty and sentenced to be hanged on July 11, 1884, the date on his tombstone. About a year after his execution, evidence came to light that he was innocent.

The haunting and subsequent legend apparently began after a seance was held in the cemetery by members of the Chi Phi fraternity. According to the campus newspaper, the fraternity brothers, unaware of any details of Will Peckham’s life, went to the cemetery in 1962:

It was a warm summer night, but the wind was still blowing strongly. They had brought a candle with them and were using it during the seance and the calling up of the spirit. It was lit on the tombstone of Peckham, but despite the strength of the wind, the flame did not flicker at all.

During the seance one of the participants in a voice not his own, called out the name ‘Nancy’, and began crying violently. Later, when questioned, the individual didn’t remember anything about the incident except arriving at the Peckham family [burial] plot earlier in the evening.

In the ensuing weeks there were several incidents involving loud noises, moving furniture and disappearing items reappearing in unusual places.

In 1965, two additional seances were held in the fraternity house for the purpose of banishing Peckham’s ghost:

“… all power in the house was cut off, the candle went out and the room became extremely cold. The same individual became possessed and this time cried out in a voice not his own, ‘no, no, no, . . not any more!’ ”

I told Brian that there were some problems with this story, the major one being that Will Peckham could not have been executed in 1884. The last person executed in Rhode Island was John Gordon, fifteen years before William Peckham was born! (Some years later I searched the Rhode Island Historical Cemeteries Database and found no Nancy Peckham that would fit the time frame.)

The stories of Will Peckham and John Gordon show some interesting similarities, including the hanging of an innocent man and subsequent seance by college students, that suggest they may have mingled in the legend conduit. Amasa Sprague, a businessman and manufacturer from a politically powerful family, left his stately Cranston home one day in December, 1843, to travel to Johnston. The following morning, his bludgeoned body was found beside the road, almost within sight of his mansion. Gordon, an Irish immigrant and employee at the mansion, had been seen arguing with Sprague the day he was killed. Gordon was tried, found guilty of murder on the basis of circumstantial evidence, and hanged in 1845. Evidence later came to light that proved his innocence. Public indignation following John Gordon’s execution led to legislation abolishing capital punishment in Rhode Island. The actual killer was never found.

For many years, Sprague Mansion, now the home of the Cranston Historical Society, has been reputed to be haunted. Visitors report seeing an astral presence. The apparition is most often observed descending the main staircase or is felt as a passing breath of icy air in the wine cellar. Likely candidates are plentiful. Until several years ago, many believed that the ghost was that of John Gordon. Besides Gordon and Amasa Sprague, himself, other suggestions have included Lucy Chase Sprague, who lost a fortune, her reputation, and her beauty; William Sprague, who died after a bone lodged in his throat during a family breakfast; or the son of Governor William Sprague, 2nd, who committed suicide in 1890. But a seance held by students from Brown University, in Providence, to determine the ghost’s identity, revealed the agitated spirit of a subsequent owner’s butler, who had expected—but not received—an inheritance. The seance was hastily concluded when the Ouija began to move violently, spelling, “My land! My land! My land!” Finding William Peckham’s gravestone—instructive and interesting, as it was—did not move us closer to resolving our immediate problem. Oddly enough, although I did not know it at the time, the Sprague family does enter into the vampire picture in a most unexpected place. But that’s a connection I would not discover for several years.

Brian and I crossed the dirt road to the “Old Fernwood Cemetery,” where we found some Rose family graves, but none that matched our needs. Finally, in the “Rose Lot,” we located and photographed the graves of William G. Rose and his second wife, Mary G. Rose. The grave of his daughter, Ruth Ellen, was not there. In October, 1982, I had interviewed Jeanne Bradley, a local historian from North Kingstown. She knew the Rose family story and told me that “the vampire’s grave” was in the cemetery across from Rose Hill on Moorsefield Road. Reviewing the audiotape from that interview, I concluded that she was referring to the cemetery Brian and I had been seeking, the “Rose-Watson Lot.” The test of that hypothesis was thwarted, at least temporarily, by the thick growth that Brian and I had been trying to penetrate.

Perhaps I should have counted myself fortunate to have gotten as far as I had with the Rose event, given the paltry and often inaccurate record. Working back from Montague Summers’ report yielded the following description, in 1879, in Moncure Daniel Conway’s Demonology and Devil-Lore: “In 1874, according to the Providence Journal, in the village of Peacedale [sic], Rhode Island, U.S., Mr. William Rose dug up the body of his own daughter, and burned her heart, under the belief that she was wasting away the lives of other members of his family.” Conway’s misspelling of Peace Dale as Peacedale was picked up by subsequent authors and, after more than a hundred years and half a dozen citations in the vampire literature, Peace Dale had become Placedale. The printed versions of this case are as vague as the few I have collected from current oral tradition. A newspaper article from 1977 hinted at a family story of the incident:

William C. [sic] Rose of Peace Dale feared an attack by vampires in 1874 because of his daughter’s recent death. The then 53-year-old man exhumed his daughter’s body in Rose Hill Cemetery just outside of Kingston on Route 138 and “burned her heart” to avoid even the possibility of vampirism, according to a living descendent of Rose.

The graves of Rose and his wife Mary A. [sic] stand out prominently in the graveyard just inside the iron gates but the daughter’s grave cannot be found. A search through birth, marriage and death certificates in South Kingstown Town hall showed no record of the family.

Evidence from genealogy and gravestones was corroborated by information in the newspaper article. It seemed likely that the girl’s father was William G. Rose, who was born in 1821 in Exeter, died on January 19, 1911, and was buried in the family plot of Rose Hill Cemetery. Rose seems never to have lived in Peace Dale, the nearest village of any size. The daughter whose body was exhumed probably was Ruth Ellen Rose, born in 1859 to William and his first wife (who died in 1863).The gravestones of both Rose and his second wife, Mary G. Tillinghast, are in a South Kingstown cemetery. But the grave of Ruth Ellen, who died on May 12, 1874 (according to her obituary in the Narragansett Times) has never been found.

My primary purpose in searching through genealogical and town records was to verify that these events actually happened. I did not expect to find a “smoking gun,” such as permission granted to exhume bodies or perform autopsies, in official records. Yet, if I could discover that the families described were real people, I would have a foothold in history. The more evidence, the firmer that foothold. So, I sought out family trees, obituaries, cemetery and burial records, organizational membership lists, and other social registers. If I had to take a leap of faith, I wanted the chasm of uncertainty to be as narrow as possible. Occasionally, the tedium paid off. I was enthralled by the rare and unanticipated connections that transformed a list of names and places into a scene so palpable that I could envision people talking among themselves.

I finally located the source of the vampire incident dating from the time of the American Revolution cited by James Earl Clauson in his 1937 article. The following story appeared, in 1888, in Sidney S. Rider’s “The Belief in Vampires in Rhode Island”:

At the breaking out of the Revolution there dwelt in one of the remoter Rhode Island towns a young man whom we will call Stukeley. He married an excellent woman and settled down in life as a farmer. Industrious, prudent, thrifty, he accumulated a handsome property for a man in his station in life, and comparable to his surroundings. In his family he had likewise prospered, for Mrs. Stukeley meantime had not been idle, having presented her worthy spouse with fourteen children. Numerous and happy were the Stukeley family, and proud was the sire as he rode about the town on his excellent horse, and attired in his homespun jacket of butternut brown, a species of garment which he much affected. So much, indeed, did he affect it that a sobriquet was given him by the townspeople. It grew out of the brown color of his coats. Snuffy Stuke they called him, and by that name he lived, and by it died.

For many years all things worked well with Snuffy Stuke. His sons and daughters developed finely until some of them had reached the age of man or womanhood. The eldest was a comely daughter, Sarah. One night Snuffy Stuke dreamed a dream, which, when he remembered in the morning, gave him no end of worriment. He dreamed that he possessed a fine orchard, as in truth he did, and that exactly half the trees in it died. The occult meaning hidden in this revelation was beyond the comprehension of Snuffy Stuke, and that was what gave worry to him. Events, however, developed rapidly, and Snuffy Stuke was not kept long in suspense as to the meaning of his singular dream. Sarah, the eldest child, sickened, and her malady, developing into a quick consumption, hurried her into her grave. Sarah was laid away in the family burying ground, and quiet came again to the Stukeley family. But quiet came not to Stukeley. His apprehensions were not buried in the grave of Sarah.

His unquiet quiet was but of short duration, for soon a second daughter was taken ill precisely as Sarah had been, and as quickly was hurried to the grave. But in the second case there was one symptom or complaint of a startling character, and which was not present in the first case. This was the continual complaint that Sarah came every night and sat upon some portion of the body, causing great pain and misery. So it went on. One after another sickened and died until six were dead, and the seventh, a son, was taken ill. The mother also now complained of these nightly visits of Sarah. These same characteristics were present in every case after the first one.

Consternation confronted the stricken household. Evidently something must be done, and that, too, right quickly, to save the remnant of this family. A consultation was called with the most learned people, and it was resolved to exhume the bodies of the six dead children. Their hearts were then to be cut from their bodies and burned upon a rock in front of the house. The neighbors were called in to assist in the lugubrious enterprise. There were the Wilcoxes, the Reynoldses, the Whitfords, the Mooneys, the Gardners, and others. With pick and spade the graves were soon opened, and the six bodies were found to be far advanced in the stages of decomposition. These were the last of the children who had died. But the first, the body of Sarah, was found to be in a very remarkable condition. The eyes were opened and fixed. The hair and nails had grown, and the heart and the arteries were filled with fresh red blood. It was clear at once to these astonished people that the cause of their trouble lay there before them. All the conditions of the vampire were present in the corpse of Sarah, the first that had died, and against whom all the others had so bitterly complained. So her heart was removed and carried to the designated rock and there solemnly burned. This being done, the mutilated bodies were returned to their respective graves and covered. Peace then came to this afflicted family, but not, however, until a seventh victim had been demanded. Thus was the dream of Stukeley fulfilled. No longer did the nightly visits of Sarah afflict his wife, who soon regained her health. The seventh victim was a son, a promising young farmer, who had married and lived upon a farm adjoining. He was too far gone when the burning of Sarah’s heart took place to recover.

Sarah returns from the grave at night to bother her living family members? Now there’s a motif I did not expect to find applied to a New England case by a nineteenth-century historian.

What do I make of Sarah’s night visits? Sarah, more monster than scapegoat, was a snug fit with the vampire of Gothic literature, but a figure ill-suited to what I knew of Mercy Brown. Mercy’s was the most recent death in her family, yet she was singled out as responsible for … what? Her brother’s illness? Then, what about Mercy’s mother and sister? They preceded her in death. Was Mercy the culprit? How was that possible? The way out of this dilemma-was to acknowledge the differences between Mercy Brown and Count Dracula as played by Bela Lugosi. A wide expanse separates the vampires of folklore from those of literature and mass media. In New England tradition, the unnamed evil resided in the perhaps locating itself within the corpse of a deceased family member. The term “vampire” was used by outsiders, never by those in the community. Once that term was applied, the familiar vampire caricature, well-formed even before Stoker’s Dracula, crept out of its coffin and into the story.

Rider followed established precedent by introducing his tale with an image drawn from Europe and well-known to the reading public. “Vampires,” he wrote, are a “comparatively modern delusion” that originated in the “lower Danubian provinces.” These “unseen beings, which, though dead, nevertheless possess some attributes of a living existence … wander at night sucking the blood of living human victims.” A vampire “developed from a human being who had died. During the day this unquiet spirit would lie quietly in the grave in which it was buried, but at night it would assume the form of some animal or insect, and wander forth, seeking and sucking the warm blood of its sleeping victim.” Rider commented that this “superstition … seems to have been prevalent at one time here in Rhode Island. In fact, it may even at this day be held in her remote regions.” He found it “strange, even incredible” that “anybody should believe in such absurd superstitions. It is true, nevertheless. There were, and there are now, those who do believe them, and the purpose of this paper is to narrate a case which took place here in Rhode Island at no very remote period. It was of a genuine vampire.”

The dream in Riders story is another one of those folk motifs that can be found in Stith Thompson’s Motif-Index. In folk narratives of all sorts, the prophetic, allegorical dream plays a significant role in foreshadowing the future and perplexing protagonists. Its roots are ancient. Pharoah’s dream, described in the Old Testament (Genesis 41), parallels that of Snuffy, and was equally puzzling until interpreted by Joseph. Armed with foreknowledge, Pharoah was able to store enough food during seven years of plenty to stave off starvation during the seven years of famine that followed. In folklore, death and misfortune are the usual conditions heralded by dreams. An English superstition specifies that “to dream that a tree is uprooted in your garden is regarded as a death warning to the owner.”

How did I interpret Snuffy’s prophetic dream? Combined with Sarah’s actual return from the dead, it suggested that someone (Rider’s source? Rider himself?) had “improved” the narrative (assuming for the moment that it was, indeed, based on an actual event).The existence of such folk motifs in a narrative did not mean that it is a complete fabrication, of course. People do have dreams that seem to predict the future. Stepdaughters sometimes are exploited by wicked stepmothers and abused by jealous stepsisters. Young boys, sent out by their single mothers to do a man’s work, have been swindled by unscrupulous traders. Though fictional, folktales (and written literature, as well) include real social relationships and cultural contexts. While the line between fantasy and reality may not be hard and fast, it does exist. When pumpkins transform into carriages and beanstalks ascend into a land of giants, that line is breached. Revenants and prophetic dreams are not so unequivocal. This shadowy region between the possible and impossible, the known and unknown, the natural and super-natural is precisely the domain of legend. Was the story circulating orally for some time, long enough to attract traditional motifs, before Rider encountered it? Everett Peck’s tale, told to me in 1981, seemed to be headed in the same direction, with Mercy turning over in the grave and an eerie blue light appearing above her tombstone. If Rider himself embellished the narrative, he may have been employing a literary convention, not imitating folk tradition. In both oral and written literature, a dream can perform a dual function. Near the beginning, it is a symbolic foreshadowing of events; at the end, it is a device of closure. The uncertainty introduced by Snuffy’s dream is resolved when he finally understands its terrible meaning: half of his orchard, half of his children, perish. Sarah’s return from the grave also may be a literary device rather than a reporting of fact. In the Gothic literature of Rider’s day (or today, for that matter), how else would a vampire behave?

The following comments by Rider raised other questions:

The conditions here narrated are precisely similar to those alleged to have taken place in the Danubian provinces and the remedy applied the same. But in those countries certain religious rites were observed, and occasionally, instead of burning a part or the whole of a body, a nail was driven through the centre of the forehead. At the period when this event took place, religious rites were things but little known to the actors in the scene, and fire in their hands was quite as effective an agent as an iron nail. Those from whom these facts were obtained little suspected the foreign character of the origin of the extraordinary circumstances which they described; but extraordinary as they are, there are nevertheless those still living who religiously believe in them.

What does Rider mean by “religious rites were things but little known to the actors in the scene”? Is he characterizing Snuffy and his community as unbelievers? Ungodly? Something worse?

In Rider’s published account, every kind of clue that might lead to further documentation or corroboration of his story, such as time, place, and person, is vague to the point of being useless: “At the breaking out of the Revolution there dwelt in one of the remoter Rhode Island towns a young man whom we will call Stukeley.” Besides the daughter’s name, Sarah, we have only the surnames of neighbors who assisted: Wilcox, Reynolds, Whitford, Mooney, and Gardner. Rider is equally vague concerning his sources: “those from whom these facts were obtained.” That’s it. End of trail?

I believed so, until January 5, 1983, when I came across a promising lead as I was checking the card catalogue for other publications by Rider at Brown University’s Rockefeller Library. Brown’s archives of special collections, the John Hay Library, contained something called “The Rider Collection.” I hurried across the street to the John Hay without even bothering to put on my jacket. The Rider Collection did, indeed, include a great deal of material compiled by Sidney S. Rider, some of it indexed and some not. I requested the material labelled “Exeter Notes” and was ushered into the hushed, high-ceilinged reading room. This “room” was actually the center portion of space that was divided into thirds by dark wood bookcases ascending perhaps a third of the way to the forty-foot ceiling. On three sides of the huge neoclassical space were generous windows. At each of the long wooden tables, one had a choice of chair styles: comfortable, stuffed or, for those who needed the feel of a hard surface to stay attentive, unadorned wood. I selected wood. The librarian brought Box 300, which I eagerly opened. My heart sank when I saw a thin brown notebook. How much information could there be in a notebook measuring five-by-three inches? Two short lines seemed positively bountiful: “Story of Stukeley Tillinghast & his digging up of his six dead children—Snuffy Stuke. “A surname was all I needed for a genealogical search that yielded a Stukeley Tillinghast, father of fourteen children, residing in the town of Exeter. On the basis of newspaper clippings pasted into the notebook, I concluded that Rider probably made this entry about 1888, not long before publishing the story in his Book Notes.

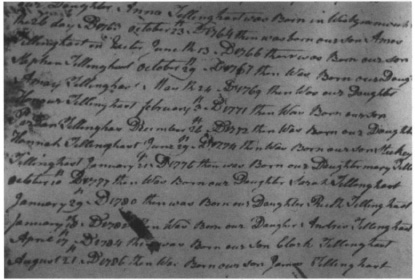

As I anticipated, I found no mention of an exhumation in the Exeter Town Records. But I did locate three sources, including the Town Records, that, with minor discrepancies, substantiated the existence of the family described by Rider. Stukeley (with various spellings) Tillinghast of Exeter, son of Pardon Tillinghast of West Greenwich, was born in Warwick on November 24, 1741, and died in West Greenwich in 1826. He was married to Honor (or Honour) Hopkins, the daughter of Samuel Hopkins of West Greenwich, on November 22, 1762; she was born in West Greenwich on January 6, 1745, and died in West Greenwich on December 3, 1831. Stukeley and Honor produced fourteen children (see APPENDIX B: CHILDREN OF STUKELEY AND HONOR TILLINGHAST for names and dates).

Records of Births, Tillinghast Family 1763–1786, Town Records, Exeter, Rhode Island. Several members of the Tillinghast family died in rapid succession. About 1799, Sarah Tillinghast’s body was exhumed and her heart was removed and burned to prevent further deaths in the family. Courtesy of Michael E. Bell.

The nickname “Snuffy” rings true to an established South County tradition, and probably was not an intrusion into the story or an invention by Rider. The names Pardon and Stukeley (of Saxon derivation, meaning “stiff clay”) were so common among the Tillinghasts that unique sobriquets had to be applied to distinguish one from the other. Snuffy’s great-grandfather, one of the many Pardons, acquired his nickname after building a wharf that became an integral part of the “notorious triangle”—the thriving, and to many, unconscionable, trade in slaves, molasses, and rum that linked Africa, the West Indies, and Rhode Island. An historian wrote that Pardon Tillinghast’s “lucrative business in rum and molasses gave him not only a fair estate, but a sobriquet which proved as lasting, and to his death he was known as ‘Molasses Pardon.’ ” The Hazard family took this practice to perhaps an extreme degree. There were thirty-two “Tom Hazards” living at one time. These included not only Shepherd Tom (author of The Jonny-Cake Papers), but also College Tom, Barley Tom, Little-Neck Tom, Fiddle-Head Tom, Pistol Tom, Nailer Tom, and Tailor Tom.

Despite the many agreements between Rider’s narrative and other sources, there are discrepancies. First, the event seems to have occurred in the year 1799, some twenty-three years after “the breaking out of the Revolution.” Also, half of Snuffy’s fourteen children did not die in close proximity, though four of his five youngest children, beginning with Sarah (b. 1777), did die of consumption in 1799. Sarah was not the first child born, as Rider wrote, but the tenth. Rider also wrote that the last to die was a son, “a promising young farmer, who had married and lived upon a farm adjoining.” None of Stukeley’s six sons seems to match Rider’s description. Four of them lived beyond their seventies and another died at age forty-seven, thirty-three years after Sarah’s death. Evidence regarding James, the youngest child, is conflicting. One genealogy lists James as dying of consumption in 1799. If this is true, he was only thirteen—young, even at that time, to be married and living on his own. But in June of 1995, a Tillinghast descendent living in Connecticut wrote to me that he had discovered a will of the same James Tillinghast. The will was dated 14 August 1810, which suggests that James lived well beyond Sarah’s exhumation. Actually, it is a daughter who most closely matches Rider’s description. Hannah Tillinghast married Joseph Hoxsie in 1797 and died three years later. Since Joseph Hoxsie resided in a village located less than a mile south of Pine Hill, it is very likely that the Hoxies lived in close proximity to the Tillinghasts.

More than a year after I found a surname for Snuffy, after examining several hundred gravestones in four Tillinghast lots in West Greenwich and Exeter, I finally located a Tillinghast family cemetery that contained at least some of Snuffy’s family. On a cool, sunny day in April, 1984, I found the small, neglected family plot on a rock-strewn hillside. Stukeley’s wife, Honor (d. 1831), was apparently the first to be buried in this plot. The most recent burial seems to have been Frank Tillinghast (1852–1919). Honor’s stone reads: “She was the mother of 14 children and all lived to grow up.” Either James or Andris was the youngest to die. In an era before the invention of “teenagers,” one who had attained the age of thirteen no doubt would have been considered grown-up. Other marked and legible gravestones included that of Stutley (Stukeley, Jr.) (d. 1848) and Clark (d. 1832), and several of Stukeley and Honor’s grandchildren and in-laws, including, perhaps, the Whitfords mentioned by Rider. Two adjacent stones are inscribed simply B.W. and A.W., which might be Benjamin Whitford and Snuffy’s daughter, Amay Tillinghast Whitford, who married Benjamin in 1794. There were five uninscribed, upright field stones in a row, perhaps marking other graves. One of Rider’s statements made me wonder if the Tillinghast house was located next to the cemetery: “Their hearts were then to be cut from their bodies and burned upon a rock in front of the house.” When I found the cemetery, there was no evidence of a nearby house (which, of course could have been destroyed long ago).

Rider’s statement that “religious rites were things but little known to the actors in the scene” seems at least untrue, if not disingenuous, in light of the Tillinghast family genealogy. It may be difficult to find a consistently more religious family, at least if measured by those who became members of the clergy—a trend that continues into the present. Stukeley Tillinghast married Honor Hopkins, daughter of Samuel Hopkins and Honor (nee Brown) Hopkins. Sarah’s maternal grandfather, pastor of the First Congregational Church in Newport from 1770 to 1803, has been called “one of the leading antislavery reformers in revolutionary America and later a heroic figure to many antislavery reformers in the nineteenth century.” Samuel Hopkins was born in Waterbury, Connecticut, in 1721, graduated from Yale, and studied, in Northampton, Massachusetts, under the evangelical theologian Jonathan Edwards, whose hellfire sermons exhorted sinners to repent and convert. Prior to settling in Newport, Hopkins served a parish in Great Barrington, the backcountry of western Massachusetts. Hopkins’ opposition to slavery was inflamed by his firsthand exposure to the slave trade in Newport, after which he worked closely in the antislavery movement with the Quaker Moses Brown of Providence, who often was opposed by his brother, John, a slave trader. Theologically, Hopkins advocated “disinterested benevolence,” described as “a Christ-like, sacrificial love of God and mankind a life of self-denial, avoiding not only the selfish pursuit of worldly things but also the selfish pursuit of his own salvation.”

I recently corresponded with a descendent of Stukeley, Rev. Harold “Bud” Tillinghast. He sent me an article he had written for the newsletter of the family’s American branch, Pardon’s Progeny, which included the observation that their “first ancestor in America was named Pardon and he had been associated with the Baptist Church in Providence, Rhode Island.” Researching the family history in England, Bud found that “the Rev. John Tillinghast, graduate of Caius (pronounced “keys”) College, Cambridge 1585, and Rector of the Parish of Streat, Sussex, in Queen Elizabeth’s time was related to Pardon.” And later, “So I found nearly 20 recordings of baptisms of Tillinghast (a half-dozen marriages and about a dozen burials), some later than John’s term as rector but recorded by another Rev. John Tillinghast who proved to be his son.” The Tillinghast family appears to have had more than a casual awareness of religious rites.

Rider wrote that “another similar case in Wakefield, Rhode Island” came to his attention after he had completed his narrative, and that “still another now is in contemplation in a family of respectable surroundings, several of the members of which have recently died.” True to form, he left me to guess the identity of these unnamed families.

The procedures used by desperate families to stop consumption were not disembodied ideas floating in the air, just waiting for the right moment to materialize. This knowledge was transmitted via the folklore process, an ancient, intimate way of communicating that has remained vigorous over the centuries, even in the face of technologies such as print, the telephone, and the Internet. As we interact with close acquaintances during the normal course of daily life, we make observations, give opinions, discuss our lives, share our burdens, seek—and give—advice, and convey other expressions that we deem important enough to pass along. This organic process is educational, informative, entertaining, affirmative. Just think about how much of this information exchange is in the form of personal narrative! In his article on vampirism in New England, Stetson makes it plain that eyewitness accounts were the primary means of spreading the awareness of the practice and validating its effectiveness. The observation in the Providence Journal that “the people of South County say they got it from their ancestors” hints at a long-standing oral tradition for the vampire practice. Social networks of relatives, friends, and neighbors must have been the medium through which these alternative approaches to disease control were transmitted. In his scrutiny of folklore processes, Lauri Honko has found that decisions regarding supernatural occurrences, including even their perception as such, often are communal activities: “A person who has experienced a supernatural event by no means always makes the interpretation himself; the social that surrounds him also participate in the interpretation. In their midst may be spirit belief specialists, influential authorities, whose opinion, by virtue of their social prestige, becomes decisive.”

Was William G. Rose one of these “influential authorities” who urged George Brown to exhume the bodies of his family in 1892? Rose was elected Worthy Master of the Exeter Grange in 1890, and he also was a member of the Exeter Town Council during that period. Brown was a respected farmer in this town of fewer than one thousand residents and, according to his obituary, a member of the Exeter Grange. I can visualize the scene following a meeting of the Grange or town council: Rose takes Brown aside and, after exchanging the usual pleasantries and small talk, conveys his sympathy over the recent deaths and illness in Brown’s family. Rose tells Brown that he, himself, had the same problem some years -earlier. As Rose reveals the procedures he followed to save his family after the medical establishment conceded defeat, he becomes, as it were, a “spirit belief specialist.” Because of his standing in the community, and his own experiences in the matter, he is an authority whose opinion is decisive. We know from accounts in contemporary newspapers that Brown, reluctant to interpret his misfortune as a supernatural event, was “besieged on all sides by a number of people, who expressed implicit faith in the old theory.” In the family story related by Everett Peck, the decision to exhume the bodies came from “twelve men … of the family” who “got together and … took a vote, what to do.” This is a crucial moment, when the supernatural nature of the problem is acknowledged, at least tacitly, and the exhumations can proceed. We don’t know if personal-experience narratives or family stories were brought to bear on this decision, but the circumstantial evidence in their favor is compelling.

We can add the Tillinghast family to the Exeter social network that was in place for interpreting vampire incidents. William Rose’s second wife was Mary G. Tillinghast, a great-granddaughter of Stukeley Tillinghast, Sarah’s father. Could Mary, who was about twenty-six when her grandfather Amos died, have listened to his stories of how, when he was a young man in his thirties, the bodies of his younger brothers and sisters had to be exhumed to stop a deadly epidemic? Could she have played the role of belief specialist in 1874 by providing her husband, William, with a family story that offered a solution to their own consumption epidemic? I know from my own experiences that children crave such family stories, and they are not soon forgotten.

The stories told by my own grandmother, Nana, fit squarely into this genre. Rather than the impersonal narration of timeless folktales, she told me—or, more accurately, acted out—only personal experience stories. And, my God, what experiences she’d had! Younger than my grandfather by some fifteen years, she was singing and dancing on the stage or traveling with the carnival while Grandpa, a career Marine, was in some foreign port of call. When the Second World War broke out, she was one of the first women to join the WACs.

Her performances were dramatic. Sitting in a chair, Nana would begin calmly with the necessary background of who, when, and where. Soon she would rise, possessed by her narrative, and pace around the room, throwing her arms about as she advanced the plot through a combination of description and dialogue. Her voice, low and throaty, would purr when she talked about a person whom she loved deeply, such as her father, George Peirce, killed by lightning in 1923 at Coal Hill, Arkansas. She would sigh, and actually cry. Often, she would look directly at me, take my arm in her hand and say my name, pulling me deeper into her story, making me feel that this performance was for me, and me alone. When I heard, “And, Mike, honey …” I felt the thrill of some impending twist. She had a good ear and well-developed visual sense. The real characters in Nana’s stories interacted in real spaces, all painted in rich detail. Her tales included incidents that didn’t seem to have rational explanations. Although Nana wasn’t religious in any conventional sense (I don’t remember her going to church), she was profoundly spiritual. She described portents, premonitions, signs, and omens—spirits returned from the dead.

Above all others, one of her stories has occupied a seminal position, spanning four generations in our family. I think one reason that Everett Peck’s story of Mercy Brown struck me so solidly was that it somehow connected with Nana’s story of her father, George Peirce, which I needed to hear again and again. After beginning my folklore studies, I recorded the story several times from both Nana and my father. In 1975, three years before she died at the age of 82, Nana gave me her last performance of “The Spirit on the Staircase.” Sitting in her small apartment in Louisville, she set the scene for me, my wife, and our very young daughter.

In the Summer of 1924, Florence (Nana) arrived at the combination home and antique store of her mother, Minnie, in North Little Rock, Arkansas, after having been away traveling with the carnival. Her ten-year-old son, Lester, my father, was being cared for by Minnie. Nana had been summoned by Minnie, who feared that her new husband, Richard, was “out of his mind” and would kill her and Lester.

“Hell, I took the next train.… Well, I got there and I went upstairs and cleaned up. Now, they slept downstairs, like in an old-fashioned drugstore. You walked in through old double doors, right in off of the pavement onto a little porch. Right down the middle was all that furniture, antique furniture. On one side was glass and clocks—Oh, God, she had the glass!—and all the antiques on shelves. When you got to the back there was a kind of hallway and a stairway that went upstairs. Across from the stairs was the bedroom downstairs and across from that was the kitchen and the dining room.”

“So, I said, ‘I’m going upstairs to take a nap. If you need me, call me, even if I’m asleep.’ ”

“Well, I was awakened out of a sound sleep. Mom and Les were crying and Mom was screaming and hollering, ‘Don’t, please don’t, don’t.’ ”

Here’s where Nana, still a handsome woman and amazingly agile, got up and began to enact the various roles, gesturing as she flitted around the room.

“He didn’t know I was in the place, and I got right up and went down. The table’s there and he was over that way and they were on the other side of the table hugging each other and he had a chair and was going to come around with it and hit them with the chair.”

“I said, ‘PUT IT DOWN! I mean put it down!’ He knew He put it down.”

“I said, ‘Come on out of there Mom, Les.’ ”

“They walked out into the hall and Mom says, ‘Don’t worry’ to Les. Richard set the chair down and stayed back in there where we couldn’t see him. He didn’t say a word. He just stood there.”

“So, Mom walks out, and I took Les and we walked over to right where the glass started on the shelves.”

Nana was in full-acting mode now.

“And here’s what Mom did. She walked over there. She faced the shelves some way or other and she put her hands up and touched one of the shelves, like to lean. I didn’t know what she was doing, what she went over there for, whether she was going to look for something or what, the way she was doing with her hands.”

“She says, ‘Dear God, please send the spirit of George Peirce back to help us.’ ”

“Lester, he’ll tell you himself, he heard it, Mom heard it and I heard it, and Richard heard it. We heard my father coming down them stairs. It’s daylight now. It is daylight, late in the afternoon in the summertime, still light. And he walked, and walked down the stairs, and he walked toward the dining room. About then that guy, Richard, come rushing out. The footsteps stopped. Nothing else happened. And that bird, he ran all the way to that corner. He got a wheelbarrow, brought it back in, grabbed all his clothes and everything, put them in the wheelbarrow, and piled all his hats on top of his head. We looked out and saw him with that wheelbarrow, and those hats on his head, going down the road, and we haven’t seen him from that day to this.”

I’ve told this family story many times. Everett often repeats his family story of Mercy Brown. Of the several themes common to family stories, supernatural occurrences are the most compelling. They challenge natural boundaries, stretch the limits of our understanding, force us to reexamine our view of the world. Supernatural stories are remarkable no matter how many times we hear them. If Mary Tillinghast Rose had not heard, and repeated, the story of Sarah Tillinghast, it would have been an extraordinary exception to our understanding of how the folklore process works.

Separated by nearly one-hundred years, these three vampire incidents involved families—the Tillinghasts, Roses, and Browns—who were linked through descent, marriage, and other personal ties. In small, close-knit communities, such as Exeter, social networks begin with kinship. Genealogy reveals more than simply who begot whom; it also charts the channels for the transmission of folk knowledge. George Stetson, James Earl Clauson, and Sidney Rider turned to European examples and literary images to make sense of events that left them bewildered. In my search for answers, I looked closer to home. What is vital in a community is recorded in the mundane features that exist at eye level. Building a narrative out of gravestones, town records, family trees, and family stories is a make-do process. Like constructing a wall from the rubble pile, you may have to “use a spell to make them balance.” If you do it well, they may sing.