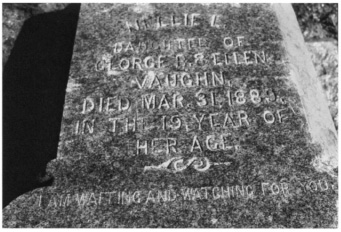

I Am Waiting and Watching For You

This inscription—provocative to some, conventional to others—appears at the bottom of a gravestone that was located in the cemetery behind the Plain Meeting House Baptist Church in West Greenwich, Rhode Island. Incised above the inscription, the following information seems mundane by anyone’s standards:

Nellie L.

Daughter of George B. & Ellen Vaughn

Died Mar. 31, 1889,

in the 19 year of her age

Why—and where—Nellie’s stone has gone makes sense if we follow Nellie’s odyssey—a strange journey that began long after her death. To answer the question of whether Nellie Vaughn was a vampire requires an entirely different approach from that employed when asking the same question about Mercy Brown. Yet, Nellie and Mercy are stubbornly, perhaps inextricably, intertwined.

Gravestone of Nellie Vaughn. The inscription “I am waiting and watching for you.” probably led to her legendary status as a vampire. Courtesy of Michael E. Bell.

The first published reference to Nellie Vaughn does not appear until 1977.

Another tale of vampirism involves Nellie L. Vaughn of Coventry [sic] who died in 1889 at 19. Her grave in Rhode Island Historical Cemetery No. 2 is the only sunken grave in the cemetery and continues to sink into the earth. “No vegetation or lichen will grow on the grave,” reports a local university professor despite numerous attempts by grave tenders and the curious. Along the bottom of the headstone are inscribed the words, “I am waiting and watching for you.”

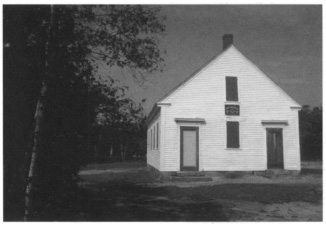

By the time this story was printed in the Westerly (Rhode Island) Sun, the tale of Nellie the vampire already had the characteristics of a well-established legend. The blossoming belief that Nellie was a vampire brought a plague of vandalism to the cemetery where Nellie was buried and to the adjacent Plain Meeting House Baptist Church in West Greenwich (not in the adjoining town of Coventry, as reported in the article).

Plain Meeting House, West Greenwich, Rhode Island. Nellie Vaughn, a legendary vampire, is interred in the cemetery behind the church. Courtesy of Michael E. Bell.

In 1982, the Providence Journal-Bulletin ran an article on the occasion of the church’s semiannual service (in itself, a fascinating custom) that contained what was becoming the accepted explanation for how, through a combination of misunderstanding, coincidence, and imagination, this legend began:

But the biggest irritant, members say, has been the constant vandalism to the church and its property, which they attribute not only to their church’s remote location but to a persistent rumor that there is a vampire buried in the church cemetery.

What was that about a vampire?

“As far as we can determine, it started 15 years ago when a teacher at Coventry High School told his students that there was a vampire buried in a cemetery off [state route] 102,” reports church historian Evelyn Smith. “The teacher never mentioned the name of the cemetery, but the students tried to find where the vampire was. They stopped here and came across a tombstone for Nellie Vaughn. She died in 1889, and her stone reads, ‘I am watching and waiting for you.’ [sic]

“The kids assumed that she must have been the vampire, and the story has just spread ever since. What we want to do now is set the record straight. There is an alleged vampire, but her name is Mercy Brown and she’s buried at Chestnut Hill Cemetery, not here. People have got the wrong cemetery and the wrong person.”

Mrs. Smith wants people to know that Nellie Vaughn was not a vampire. “There is a man in our congregation who is 100 years old who knew Nellie personally. He says there was no talk of her being a vampire while she was living or after her death.”

Nonetheless, the story about Nellie persists, she says. And hardly a day goes by without people showing up at the cemetery to look at the woman’s grave. Tombstones have been overturned. There even appears to have been an attempt to dig up the coffin.

Some town residents believe that legend trips by vandals explain why Nellie’s grave “continues to sink into the earth” and “no vegetation or lichen will grow on the grave.”

Gravestone of Nellie Vaughn. Part of Nellie Vaughn’s legend is that no grass will grow on her grave. Courtesy of Michael E. Bell.

Just over a year after this article appeared, I drove out to the West Greenwich Town Hall to see what I could find out about Nellie Vaughn. I arrived during a time of transition, as Mary Ann Brunette had just succeeded Cora Lamoureux as Town Clerk. Cora was a tough act to follow. She was, perhaps, the oldest town clerk in New England when she retired at age 87, with twenty-seven years in the post. And her uncle was Town Clerk for the thirty-four years before Cora’s tenure! Mary Ann was conversing about this and that with two middle-aged women and an older man—nothing that seemed like pressing town business. Good! I introduced myself and explained that I was interested in stories passed around town by word-of-mouth. It didn’t seem wise to jump right into the Nellie Vaughn issue. I was more than aware of the local resentment over Nellie’s—and the town’s—apparently unwarranted notoriety.

I asked about how the nearby Nooseneck Hill got its name. Surely there must be an interesting story behind such a name (pronounced “newsneck” by locals). I was offered two different explanations: it was an area where local Native Americans set nooses for capturing deer or, alternately, it was named after the bend in the river or, perhaps, the road. The storytelling session was now underway, and I was told several urban legends that were circulating at the time. Of course, they were told as true, having happened to some FOAF (friend of a friend) of the narrators. In “The Hatchet in the Handbag” (or “The Hairy-Armed Hitch-hiker”), a man is dressed as a woman and hiding, with his hatchet, in the backseat of a car. I was told this happened at the Warwick Mall. I heard two versions of “The Dead Cat in the Package.” In one, a woman hits a cat with her car, and, feeling sad, places it in a paper bag and slips the bag under her car while she goes into the mall. Another person sees her hide the bag and, thinking it must contain something valuable, takes it into Newport Creamery (a local restaurant chain), opens it, and faints. In the other version, the bag is placed on the passenger side of the car seat and is taken to a Chinese restaurant near the Warwick Mall. Finally, I was told about a woman shopping at Ann & Hope (a local discount department store—an institution, actually—that recently had to shut its doors forever) who lost track of her little girl. When she reported to the manager that she couldn’t find her daughter anywhere in the store, the doors were locked and a search undertaken. The girl was found in the men’s room with a man who was still holding the scissors that he had used to cut her hair very short. The woman who told this story, known as “The Attempted Abduction” to folklorists, said that she had heard it from a grandparent of the little girl.

Having established my genuine interest in legends, I broached the subject of Nellie Vaughn, and was grateful when the new Town Clerk checked the records instead of telling me to mind my own business. According to the death certificate and other records on file, Ellen (“Nellie”) Louise Vaughn died of pneumonia at the age of eighteen on March 31, 1889. None of the records mentions heart-burning or any other practices associated with the vampire tradition. According to those present, Cora Lamoureux believed that Nellie had first been buried on the family farm (still a common practice at the time) on Robin Hollow Road and then moved to her current resting place, one of the first public cemeteries in the area. The records showed that Nellie’s mother was given permission, on October 26, 1889, to remove the remains of her daughter to the “Plain or Washington Cemetery.” Another woman at the town hall suggested that Nellie’s story might have begun when her body was moved, an act which would have required exhumation. That intriguing possibility was enhanced when I came across a general superstition stating that “to exhume a body and rebury it in another grave makes the spirit restless forever.” A third woman seemed to bolster the latter’s opinion when she asserted that she had heard the story “for a long time,” which, she said, meant “longer than ten or twelve years,” the approximate time frame suggested by those who attribute the story to a Coventry teacher. She told me that her husband was the workman who had done the plastering for the crypt situated next to Nellie’s grave. He told her that Nellie’s stone was “too modern for 1889” and must have been a replacement. He said that the inscription was probably copied exactly from the old stone. I left the West Greenwich Town Hall still believing that, in all likelihood, Nellie’s reputation as a vampire was unwarranted. But I was open to contradictary evidence.

At the suggestion of the town-hall folks, I arranged an interview with Cora Lamoureux, esteemed for her encyclopedic knowledge of the town, and Blanche Albro, known in the community as the town historian and genealogy expert. If these two couldn’t set the record straight regarding Nellie Vaughn, I doubted that anyone could.

I pulled up to a small red cape on Weaver Hill Road, just south of the Coventry town line. In the front yard, white and purple crocus were winning their annual struggle against gravity, while the old farm buildings across the road appeared ready to give up after a century or so. Inside the parlor, Cora and Blanche talked a little while about their upbringing and their ties to the community. Cora joked that she was a newcomer to West Greenwich, having lived in the town for only about fifty years. She was born on a large farm in rural southwestern Cranston, but had long-standing family ties in West Greenwich. She and Blanche are related through several lines.

Cora said that Blanche “knows all about Nellie Vaughn. She’s the town historian. And my father would have been related to Nellie Vaughn if he had been alive at the time.”

Blanche seemed both plaintive and annoyed when she interjected, “We can’t understand why they keep bringing it up. We lived here all our lives and never … it was a schoolteacher in Coventry that started that rumor. And that’s the first time. And we tell and tell everybody it’s not true, but it doesn’t amount to anything.”

I tried to soften Blanche’s indignation by suggesting how, from a folklorist’s point of view, a rumor can become a legend and then continue of its own accord, whether or not it’s based on fact. “I think once a story starts, it’s very difficult to stop it.”

I brought out a map so that Blanche could show me where the Vaughn family had lived. She verified what I had learned earlier, that the family farm was located on Robin Hollow Road. I mentioned that there were other verified cases of the vampire practice in Rhode Island, including several in Exeter.

“Yeah,” Blanche responded, “but we never had one ’til this kooky teacher. And the only reason she started it, ’cause it says, ‘watching and waiting for you’ on her stone in the cemetery … She told the story in high school, Coventry High School, and my nephew was there. And from then on, all they’ve done is dig that grave up. If I ever told you the things that have been done in that cemetery … because these kooky people think they’re going to dig Nellie Vaughn up. They have tried it.”

Cora jumped in. “Blanche, do you think that the monument that’s up at Plain [Cemetery] is the one that used to be on the farm? Or is it a new one.”

Drawing out her first word and speaking deliberately, Blanche seemed unsure. “I … think … I don’t know. But I think, maybe, it was a newer one because, usually, back there, then, when she died, they were white marble. And this is like a gray granite, with a polished surface. I haven’t been up there in a couple of years.”

Cora added, “But that inscription … I’ve been to Plymouth—you know, the old cemetery there—many times. It’s on an awful lot of stones there. I mean, there’s nothing unusual about it.”

I began fishing for a possible alternate explanation for the story’s genesis, independent of the teacher from Coventry. “I talked to one woman at the Town Hall last Fall and she said maybe the story got started because they moved her grave.… Probably from the farm out to the church.”

Blanche responded, “You know when they moved her grave? Six months after she died. And I think they moved it because … Plain Meeting House Cemetery had been built, and was a big cemetery. And you can find in the records where loads of people took their dead out of these little individual farm cemeteries. They moved them there. When Ellen Vaughn asked, … she got permission to move that girl’s body.”

I asked how long ago the teacher had told the story. Blanche replied in her slow, deliberate fashion: “I would say between ten and fifteen years ago, because my …”

I interrupted to ask, “Do you remember her name?

“No.”

“Because I would like to contact her and find out why she told the story.”

“I don’t know. From what my nephew said, it was just because the stone said ‘watching and waiting for you.’ ” Blanche became emphatic. “We had never, never, in this town, we had never heard there was a vampire in this town. And I don’t believe …”

Cora interjected, “It’s all a new thing.”

“It’s all a new thing,” Blanche echoed. “We have asked people not to publish the story because the minute it comes out in the paper they go up there by the hundreds.”

“It’s been in the newspaper,” I observed.

“It has been, loads of time[s],” Blanche said. “And they just vandalize the cemetery. They drive right over the graves, and all such things.… I’m sure it’s fiction, because I have read all of the West Greenwich Town Council meetings, from the time the town started. And if you know about old town-council meetings, they tell everything that went on. Somebody wanted a divorce, the town talked it over. I have never found anything about this Nellie Vaughn and vampires.”

“It would probably turn up in print somewhere,” I said, indirectly reinforcing Blanche’s conclusion. “Nellie Vaughn died of pneumonia, anyway, and not consumption, which usually … was the disease that was related most to that practice.” I thought for a moment, and added, “Actually, the people involved didn’t call it vampirism, anyway. It was a way to prevent consumption. It was a medical practice.”

Cora said, “We were talking about it today, my niece and I, what they used to do if you were sick. They’d bleed you. No wonder you died, after they took half your blood out of you!”

Blanche said that she had no idea who the schoolteacher was, and reiterated her belief that the whole story is fiction.

“Besides,” I said, “there were no other members of her family who …”

Blanche interrupted, “She had half brothers and sisters, but they’re all dead.”

“I know. But were they getting sick at the same time she died?” I wanted to know.

Blanche answered, “No. The father died four years later.” Then she consulted some notes she had with her and said, “I can tell you. Her father died in 1902, so he didn’t catch nothing from her, did he? She had one sister that had died twenty years before, half-sister, eleven years old. Another sister, half-sister, she was the only child by his second wife—George Vaughn’s second wife. I don’t know when she died. Cora would. Another half-sister was Georgiana Vaughn … and she died in 1933. So, she didn’t get nothing from her.”

We discussed these family connections and agreed that the usual vampire circumstances did not exist.

Blanche continued her genealogical report. “And her mother died … her mother was Ellen Knight Vaughn. She was the second wife. She died in 1926. So, usually, like you say,” she turned to me, “when they say a vampire, two or three sisters had died at the same time, and they say, ‘Oh, the vampire … come out … and sucked their blood’ and all this foolishness. Well, her brothers and sisters didn’t.”

Cora brought up the Brown case in Exeter, and Blanche broke in. “But, this one, we never heard about it. And it irritates you to think some foolish remark would’ve started what they have done to that cemetery. That’s what irks me, is when I go up there, and.… At one time—I’ll give you a laugh—they’d go up there at night, and there’s dope and beer and all this, and they’d have their party. I used to keep check on ’em because my husband has got family that’s buried up there. They would take all the bouquets off of the other graves and put them on Nellie Vaughn’s. Then they had a spell that they left money on Nellie Vaughn’s grave. It would only be change.”

Cora asked, apparently astonished, “Did they really?”

Blanche’s voice raised an octave when she responded, “Yes they did. And I could tell you the fella that went everyday and picked up the change and put it in his pocket. And he’d say, ‘If they’re … damn fool enough to leave that change,’ he said, ‘I’ll be dumb enough to pick it up.’ He said, ‘Let ’em think Nellie Vaughn’s come out and gone somewhere.’ ”

Which may be exactly what they want to believe, I thought. The man who picks up the change may be reinforcing, inadvertently, Nellie’s legend by providing legend trippers additional evidence that she leaves her grave at night and roams the countryside.

Cora began to laugh as Blanche continued. “And he’d go two or three days later and pick up all the change. Now, you know, that gets disgusting after a while.”

Cora, still laughing, said “Isn’t that crazy! I never heard that.”

Blanche continued, “I knew a lot of the people that live in that vicinity, that they were like us. We’d hear about ’em being up there and tipping over stones. So the next day, my husband would say—his grandfather and grandmother were buried up there—he’d say, ‘We’ll go up and see if they’ve knocked over my grandfather’s and grandmother’s grave, because we’ll have to have it put back up again.’ Well, we’d get up there and we’d meet some of these other people that were doing the same thing that we were doing—to see if their family’s stones were …” She paused, then exclaimed loudly, “They’re still doing it! Last Halloween we had to drive them out of there. They’re worse at Halloween.”

Cora elaborated, “And Blanche, all of our police department, with three or four cops, have to spend the whole night there because so many people get up there. The street will get so crowded that you’d have to walk a mile or two to get there, right? Because they’re parked all along the road.”

“Where do they come from?” I wondered.

Blanche answered, “They come from Coventry, they come from North Kingstown, all the high schools! All high school kids.”

Blanche summarized, “Well, I hope it does you some good, but like I say, I don’t think she was a vampire. I know she was never called a vampire. My husband has died and his people all lived and grew up around that cemetery, and they had never heard it.”

“That’s convincing,” I said.

“Yeah, it stops you,” Blanche responded. “You know, when they started telling it and they went up there and, of course, you know how they keep adding to it. And it’s just not true.”

Thinking out loud, I said, “Yeah, that’s the process of legend formation.”

Blanche persisted. “To me, it’s not true. I don’t see how it can be true. Everything I’ve looked for and found—I can’t find nothing.”

Blanche said West Greenwich had an appreciably larger population at one time. Later, when I checked the record, I was surprised to see that the town’s population peaked at 2,054 in 1790.

“For some reason,” she said, “in the late seventeen hundreds and early eighteen hundreds, whole families moved right out, and went to, like, New York, New Hampshire, and Vermont. Because, for one thing, they were giving them property, especially Vermont and New Hampshire. Well, now, of course, genealogy is a big thing. So, people in Vermont or, I’ll say, New York, they can trace back four or five generations. They find out that their great, great, great grandfather come from West Greenwich. So, they’ll write. Well, I find what I can in West Greenwich. A lot of times they’ll send me a whole big pamphlet. With what I add, and what they’ve got, it will bring ’em right down. Well, I think that some day—not now, ’cause I use ’em—I will put them in the West Greenwich library. In years to come, if somebody else is looking up that same family, they will have that all together, you know.” When I asked, Blanche told me that the West Greenwich town council records go back to 1741, when West Greenwich was divided from East Greenwich.

I thought about how the narrators I had interviewed laid the foundation for their stories with family connections and sprinkled their discussions with genealogy. Who is related to whom, and through what line, has an obvious import to these people, rooted, as they are, in their communities. And, following their lead in this matter, I was finding that genealogy pointed toward how the vampire practice had spread in the region.

The topic shifted to records and accessibility to information. Cora and Blanche agreed that, prior to about 1850, there were no medical records, and that, even after that, death records were just entered in the town hall. Blanche said that she believes that, in many instances, people “just didn’t bother” to keep records.

To illustrate her point, she discussed her experiences with death entries in the town records. “When I was going through the town council records … in the early 1800s, somebody would die—and evidently they died suddenly—I’ll just say drunk, and they were found in a field or something. So, the town council would appoint a committee of three men—and I knew by the names they weren’t doctors, they were just men, probably the neighbors—to investigate that person’s death. That’s all you’d see! There wouldn’t be anything in the next meeting. The man was dead, that was all. They never mentioned it again.”

Cora concurred, “There was no report, or anything.”

Blanche continued, “So, then I’d go get the book—because we have the death records after 1850. By then, you were supposed to record the deaths. They had passed a law in Rhode Island. Before that, you did it if you wanted to.… I’d go look in the death records—nothing!”

Cora asked, “Didn’t they bury them, sometimes, right off on their own farm, anyway? Nobody knew about it. And not always in one place on that farm.”

Blanche came right back with an illustrative story. “My father told, when he was a young boy, maybe ten years old … I could tell the names, but I forgot.” She lowered her voice to almost a whisper and repeated, “I could tell the names.” Her tone of voice led me to conclude that perhaps she hadn’t quite forgotten.

She continued. “There was this young man and another one, and they were drunk.… And they could come from Nooseneck into this section with, I call ’em woods paths—they were just paths, like in back of my father’s house there was a wood path that would take you right over into the village.… And these two people lived on Fish Hill, which would have been over there [pointing]. They’d come through my father’s property. Then there’s another wood path that goes over onto Fish Hill. And he’d say they were always drunk, anyway. So, this day, one of ’em come runnin’! And he said, ‘So-and-so is dead. He’s in a puddle. He’s dead.’ My father said he didn’t believe him. And his father said to him, ‘You run out there and pull him out of the puddle.’ And my father said when he went out there, he was dead! He fell facedown in the puddle, and the other one was so drunk, you know, he didn’t know enough to help him out.”

Cora interjected, “And he was too drunk to get out himself!”

Blanche agreed. “Yeah. And he was too drunk. And he died. And he’s buried down Maple Road. ’Cause one time, my father took me down there and he said, ‘This is where so-and-so’s buried.… That’s the one that fell in the puddle,’ he said, ‘and I was about thirteen,… and when I went out and pulled him out of the puddle,’ he said, ‘so-and-so was right! . . He was dead.’… And I don’t think that death was ever recorded.”

Cora again concurred. “Oh, no, sometimes they didn’t record them right away. They didn’t have to. And they’d come in and record five or six at a time, sometimes. I suppose they did that in all the old towns.”

Blanche picked up the thread. “The family would come in and write down the whole list, and then sometimes on the bottom of the page, it says, ‘recorded such a year’ and sometimes it don’t say nothin’. But if you look at it close, you can tell it’s all the same handwriting and same pen and everything.”

Their discussion of the casual approach taken to record keeping, at least prior to the latter part of the nineteenth century, reinforced my hunch that it would be very difficult to find the smoking gun—a recording in the town council or other official records of permission to exhume a body.

The interview with Cora and Blanche left me feeling like an unwelcome guest in town. They were pleasant and friendly, yet I sensed that they really would prefer that I—and everyone else who was interested in Nellie Vaughn—would just disappear, forever. While both were steeped in local history, neither put much stock in local legends. I was unable to win over Cora and Blanche, even though I tried several times to communicate that my concerns as a folklorist were not predicated on Nellie being a vampire, and that the legend process, the actual focus of my interest, would continue whether or not Nellie was, in truth, a vampire.

Two weeks before Halloween in 1995, I received a phone call from Evelyn Arnold, formerly Evelyn Smith, the church historian mentioned in the Providence Journal-Bulletin article of 1982 who deplored the vandalism to the Plain Meeting House Church and cemetery by Nellie Vaughn legend trippers. Still the caretaker of the church and cemetery, she was irate over a recently published article in a local periodical that recounted the story of Nellie Vaughn as a vampire. The author had credited me with providing him information for his article, which I did in the form of newspaper articles and other references he could pursue. In effect, Evelyn asked why I would tell people that Nellie was a vampire. The continued publicity, she said, leads to ongoing vandalism at the church and cemetery. She gave some examples, including the preceding Friday (which happened to be October 13th!) when thirty cars, including the entire high school soccer team from a nearby town, converged on the cemetery.

I assured Evelyn that I did not tell people that Nellie was a vampire, that I always made a point of stressing the likelihood that it is a case of mistaken identity. I told her that, even though I share with the public the materials I have collected as a public-sector scholar, I have no control over how people, including the press, interpret the materials I supply. I avowed that, as an academically trained folklorist, I attempt to sort out history from legend, fact from fiction. Unfortunately, I said, many others do not take this approach. I also told her that, when I speak to the press or the public directly, I make a plea that people respect both the families and sites that have been incorporated into local legends.

Since I had not seen the article she was referring to, I asked her to send me a copy. A few days later I received both the article and her letter of response to the newspaper. Following are excerpts from the article, which appeared in the North Kingstown Villager:

Many in [North Kingstown] know the story of Mercy Brown, the vampire of Exeter, who was exhumed and whose heart was burned to ash on a stone near her grave. She was blamed for the failing health of her brother Edwin, and for the deaths of her sister and mother. The ritual, supposed to rid the corpse of the vampire spirit, failed to save Edwin Brown. Many now believe that the family died of consumption, the 19th century name for tuberculosis.

But the stories of Rhode Island vampires do not end with Mercy Brown. Just a few miles to the north, in the town of West Greenwich, lies the body of Nelly [sic] Vaughn, who died in 1889 at the age of nineteen. Etched in her headstone is the inscription, “I am waiting and watching for you.”

Nelly Vaughn was thought to be a vampire at the time of her death. To this day it is claimed that nothing will grow near her grave, in spite of many attempts to plant there. Now for the frightening part: At least 12 people have reported seeing, hearing or feeling the presence of Nelly Vaughn while visiting her gravesite. Her ghost has often been heard to say, “I am perfectly pleasant,” but it has also been known to scratch the face of those who may not agree. One [woman] mistook the spectre for an insane person before the spirit vanished.

… These stories are purported to be true, but like many such stories, they can be explained away by facts or are examples of superstitions and folklore carried from generation to generation. Some curious individuals who have wished to test the validity of these stories and/or just to frighten themselves have been the cause of the desecration of several historic cemeteries. Please remember that while the folklore is a matter of public record, the people which the lore surrounds are very precious and private.

Special thanks to Michael Bell, Rhode Island State Folklorist, for his help in unearthing these haunting tales.

I was not pleased to see my name attached to the article, particularly because the author wrote that Nellie “was thought to be a vampire at the time of her death.” I remembered telling him that the opposite was probably true. At least he passed along, indirectly, my appeal for would-be legend trippers to show proper respect for the places they visit.

The text of Mrs. Arnold’s undated letter to the editor follows:

I am writing to dispute Chris Carroll’s story, Local Haunts in the October 1995 issue. The story of Nellie Vaughn is not true. In the early 1970’s a high school teacher told his students about a 19 year old girl [whose] body was exhumed. Her family thought she was a vampire … The teacher was talking about Mercy Brown. When the students found Nellie Vaughn, they were sure that they had found the grave. The students were wrong, but the rumor continues.

Before the mistake in identity, grass always grew on the grave. When grass is constantly being trampled, and dug it will not grow. Nellie’s stone has been broken into chunks, and stolen. Now that no one can find the grave, the grass grows. No grass has ever been planted there. I have gone to this cemetery all my life, and have witnessed this myself.

A man who died at the age of 101, in the 1980’s, knew Nellie when he was a child, before or after her death. This man told me himself. Much vandalism has been caused because of this mistake.

Evelyn Arnold told me that Chris Carroll got most of the information for his story from the 1994 book, The New England Ghost Files, by Charles Turek Robinson, which includes eye-witness accounts by people who have reported supernatural occurrences while visiting Nellie’s gravesite. Robinson’s entry for Nellie Vaughn recounts the belief that no grass will grow on her grave, then launches into personal experience stories. Several people, including two “former town officials,” have reported seeing a young woman dressed in Victorian attire in the cemetery, especially around Nellie’s tombstone. When approached, the specter disappears. But, according to Robinson, “the most common manifestations have been auditory. A number of people claim to have heard the disembodied voice of a young woman speaking out in the vicinity of the grave. In all instances, the faint voice was heard to be repeating the curious phrase, ‘I am perfectly pleasant.’ ”

The bulk of Robinson’s narrative recounts the experiences of Marlene, a woman from Coventry who visited the site several times in 1993. On her first visit, Marlene was attempting to obtain a rubbing of Nellie’s gravestone, but her paper kept showing moisture stains even though the stone was completely dry. Adding to the mystery, her charcoal stick disappeared. She gave up on making a rubbing of the stone and took some photographs of Nellie’s stone and several others in the cemetery. When she got the photos back from the developer, all of the gravestones were normal except Nellie’s. In every photo of her stone, the letters appeared backwards. Marlene returned to the cemetery with a friend a few weeks later. In front of Nellie’s grave, her friend could feel, but not see, someone poking her arm. But it was Marlene’s husband, during a subsequent visit, who first heard the female voice in front of Nellie’s tombstone say, “I am perfectly pleasant.” He also felt something “invisibly scratch him across the left side of his face.” And, according to his wife, “he had several red marks to prove it.” He never returned to the cemetery.

Marlene went back alone several days later, where she encountered an attractive young woman. As they walked among the gravestones, chatting, the woman said that she was a member of some historical society. They stopped at Nellie’s stone and Marlene asked the woman what she thought about the vampire legend. The woman said that she thought the legend was silly because Nellie had not been a vampire. At that point, the woman’s behavior changed, and she began to repeat, “Nelly [sic] is not a vampire.” Marlene, alarmed, returned to her car. As she glanced back at the cemetery, she was “astonished to see that the strange young woman was no longer there.” On reflection, Marlene came up with the following theory to explain Nellie’s haunting of the cemetery:

… Nelly is trying to vindicate herself. From the time of her death—perhaps because of the strange inscription on her tombstone—local folklore has mistakenly designated her a vampire. Marlene thinks that the young woman cannot rest with such a black slur on her name. For this reason, her apparition often appears troubled, and the ghost is sometimes heard to be saying “I am perfectly pleasant.” [sic] as if to counter the notion that she is somehow evil.

Now, as these recent accounts of encounters with Nellie enter oral tradition, particularly the “I am pleasant” incident, a new legend appears to be forming. In this updated version, Nellie is longer a vampire; she is a ghost attempting to clear her name. Currently, then, there are three distinct Nellie Vaughn legends:

Legend 1. Nellie is a vampire;

Legend 2. Nellie is not now, nor has she ever has been, a vampire;

Legend 3. Nellie is a ghost on a mission to let people know she was never a vampire.

Legend 3 relies on legends 1 and 2; it is, in fact, a combining of them that acknowledges the existence of the “Nellie is a vampire” legend but accepts the truth of the “Nellie was never a vampire legend” to explain why Nellie’s ghost haunts the Plain Meeting House cemetery.

All of the elements necessary for the marriage of a legend with the legend tripping custom exist in the first legend:

• The story is set in a specified locale that is relatively isolated yet readily accessible by automobile;

• the core of the legend involves some sort of supernatural crisis;

• the supernatural crisis has never been resolved; therefore,

• there is a threatening presence at the legend’s locale; so,

• something spooky, mysterious, and even dangerous, might occur there.

A legend trip transforms a mere story into an event. Visitors to a legend’s site become more than a passive audience as they literally step into the tale and become actively engaged in its incidents. They are, themselves, shapers of the tale. Any experiences that seem out of place or inexplicable, such as strange noises or creepy feelings, are likely to become incorporated into the legend, as these weird events are reported to friends and classmates. Legend tripping provides not only a setting for storytelling, but also the experiences that feed back into the legend and continually re-create it.

It is, no doubt, this process that accounts for the elements that have been incorporated into the legend of Nellie as a vampire. And, not surprisingly, most of them have a documented existence in folklore. After all, our underlying well-spring of folklore informs us about the nature of the supernatural world, guiding our interpretations. What is the meaning of no grass growing on Nellie’s grave? There might be an explanation that does not have to resort to the supernatural. Some spoilsport, like Dr. Killjoy Rational III, might attribute the lack of vegetation to the tramping feet of legend trippers. A more satisfying solution—one that sustains, rather than undercuts, the legend—is found in numerous folk narratives: Grass does not grow on a murderer’s grave. A vampire, of course, is a special genre of murderer.

Nellie’s sinking grave also has rational explanations—legend trippers walking on, and even attempting to excavate, her grave, for instance—that can be ignored in favor of more ominous, but reinforcing, folk connections. A widespread American superstition states: “If one’s grave sinks very much, another member of the family will die soon.” In this form, the belief makes no explicit connection between the corpse in the grave and any subsequent deaths; the sinking grave is merely a sign, not a cause, of an impending death. But, in some European examples, the causative link is clearly stated. An early nineteenth-century Serbian Schoolbook warns, “If the grave is sunk in, if the cross has taken a crooked position, and [if there are] other indications of this sort, [they] suggest that the deceased has transformed himself into a vampire.”

Leaving money on Nellie’s grave also relates at least indirectly to a variety of folk customs. The practice of supplying the dead with money (or some other form of exchange) to assist them in their journey to the otherworld is so ancient and widespread that it hardly needs discussion. Whether seen as a form of bribery or simply as a way to move the dead out of this world and into another, the outcome is the same: the dead will not return to bother the living. Ancient Greeks paid the ferryman to deliver them to the otherworld. African-American voodoo practitioners leave money on a grave to “pay the spirit” for taking his graveyard dirt for ritual use. In Romania, the corpse is given a coin, candle, or towel to prevent it from becoming a vampire. The following account, recorded in Illinois in the 1930s, shows that this ancient custom was carried into twentieth-century America: “Another thing my mother did if anyone died, she always put some money under their pillow so they could have money to travel on. She did this to my brother forty years ago, put two silver dollars under the pillow in his coffin so he would have money on his way.”

The folk motifs that have been incorporated into the legend of Nellie the vampire—no grass growing, the sinking grave, and the disappearing money—provide legend trippers with the tangible evidence they need for believing that the door to the supernatural realm remains open. That some Dr. Rational might interpret these phenomena without resorting to the supernatural does not lessen their impact for those disposed to believe. After all, one can point to alternative explanations that are widespread and long-established in folklore. Could so many people in so many places be wrong for so long?

For a very long time I never considered the second legend of Nellie a legend at all; it was, simply, THE TRUTH. I changed my mind after some reflection stimulated by a recent experience.

In November of 2000, I gave a talk at a meeting of the Western Rhode Island Civic and Historical Association. It took some patience and ingenuity to set up my slide projector and tape recorder in the cellar of the organization’s seventeenth-century house in Coventry, since the electrical outlets were added long after the house was built but well before the advent of grounded plugs. As my wife searched for a three-pronged adapter and I struggled to remove a hot lightbulb from an overhead fixture so that I could replace it with a primitive screw-in outlet, I made small talk with arriving members. Actually, what most people think of as small talk often is, for me, fieldwork, part of a process for learning, firsthand, about local folklore. I was not surprised when told that the house was haunted. Any house that is more than three-hundred years old has to be haunted, if it has any character at all.

The towns of West Greenwich and Coventry were well-represented, so I raised the topic of Nellie Vaughn. Naturally, the origin of the legend was discussed. A woman from Coventry said that she did, indeed, know the identity of the teacher who started the whole thing. When I pressed for specifics, such as an actual name, I was told that, well, she would have to track it down—but she promised to get back to me with all of the information I requested. As weeks became months, I contemplated the elusive quarry. Then it struck me, not slowly, in logical increments, but in a single, unified flash. The TFC (teacher from Coventry) is a FOAF (friend of a friend). How many times had I heard the explanatory story? Countless. From how many people? Ditto. Had anyone ever given me a name? Never. Moreover, the teacher has been both a “he” and a “she.”

By calling the story a legend, I’m neither asserting nor assuming that it’s untrue—just merely acknowledging what I finally recognized: it has all of the defining characteristics of a legend. The story is set in the real world of historical time, with authentic places and credible characters. Although it is told as true, and the realistic setting with ordinary people in everyday situations provides an air of veracity, its truth is open to question. It is essentially a conversational story, loose and shifting in narrative form, revolving around the stable idea of mistaken identity. The actual words change, but the core of the story is always remembered and repeated: Nellie Vaughn is not a vampire. The story circulates primarily by word of mouth, communicated face-to-face, from one person to the next, although occasionally it is printed in a local newspaper. No one knows who first told the story. It has become a community’s story, providing the insider’s view of the issue, balancing (some hope, canceling) the outsider’s story that continues to attract legend-trippers.

The story, though unverified, appeals to my rational instincts. Sometime in the late 1960s or early 1970s, a teacher at Coventry High School told his or her students about a vampire, probably Mercy Brown. Did she forget Mercy’s name? Or did he omit Mercy’s name purposefully because he didn’t want his students to visit and vandalize the cemetery? Perhaps the teacher said that the vampire was a young woman who died sometime around 1890, and was buried in a cemetery behind a Baptist church south of Coventry, located off Victory Highway. Of course, one dark Friday or Saturday night, some of the students, armed with their limited knowledge, set out on Victory Highway in search of the vampire’s grave.

Victory Highway (Route 102) is the main artery connecting Rhode Island’s western towns that border Connecticut. This two-lane blacktop, which begins in the small mill village of Slatersville, near the Massachusetts border, meanders south through the towns of Burrillville, Glocester, Scituate, Foster, and Coventry. In West Greenwich, it arcs gently toward the southeast until it junctions with Ten Rod Road in Exeter. At that point, it makes a beeline due east to its terminus in North Kingstown at Wickford Cove on Narragansett Bay. Victory Highway’s fifty miles traverse the most isolated, desolate areas of the state. Two vampires, Mercy Brown and Nellie Vaughn, are buried within sight of the highway in Exeter. Sarah Tillinghast is likely interred in an unmarked grave in her family’s small cemetery about two hundred meters north of Victory Highway, just east of its junction with Ten Rod Road. But, until I discovered the family name and located the cemetery in 1984, no one would have known who Sarah was or where she was buried. Not three miles down the highway toward Wickford is the Exeter Grange and Chestnut Hill Baptist Church, behind which is the grave of Mercy Brown, Rhode Island’s most notorious vampire.

As the legend goes, the students came upon the Plain Meeting House Baptist Church and cemetery in West Greenwich, the town located between Coventry and Exeter. They never made it as far as the Chestnut Hill Baptist Church. As they pulled up to the diminutive Plain Meeting House, with its windows ominously shuttered, they could see, dimly lit by the headlights, the beckoning stone pillars of the cemetery’s entrance. It didn’t take long for the flashlight beam to hit upon the gravestone that was just to the right of the dirt road, only a few meters in from the entrance. The students let out a spontaneous gasp/scream when the light fixed on the inscription at the bottom of the gravestone. As they read aloud, “I Am Waiting and Watching For You,” poor Nellie’s fate was sealed through mistaken identity.

West Greenwich, Rhode Island. The entrance to the cemetery where Nellie Vaughn is buried. Courtesy of Michael E. Bell.

One glitch in this reasonable scenario is that the Plain Meeting House is not at all visible from Victory Highway. One must travel west on Plain Meeting House Road for about four miles, with many curves and sharp turns. Maybe some of the students already knew about the church and cemetery and decided it was a likely place to search? Another question: What does the inscription on Nellie’s gravestone mean? If you’re thinking about some undead creature entombed under the stone, surely it has a threatening aura. But, take a step back, adopt the persona of Dr. Killjoy Rational, and ask some follow-up questions: Who would have chosen that inscription? Traditionally, it would have been Nellie’s parents. Why would they have chosen this seemingly ambiguous statement? Viewed in the context of conventional tombstone inscriptions, it is neither threatening nor ambiguous. This phrase is found on the stones of family members who died while in the flower of youth. In heaven before fulfilling their earthly promise, they await a reunion with loved ones left behind. But, even if Nellie’s body had been exhumed as part of a healing ritual, why would it be necessary to post a public warning? Dr. Rational answers: procedure finished, vampire laid to rest, end of threat, mission accomplished.

The stable core of this legend—that Nellie’s vampire reputation is the result of mistaking her for Mercy Brown—has been borne out over the years as people continue to confuse the two. Take, for example, the Providence Journal article by reporter Kevin Sullivan, “A Journey through Old Rhode Island: Quietly But in Vain, The Rural Areas Try to Fend off Modernity,” which appeared in May 1990:

… just before dark, we arrive at West Greenwich Center, which is the center of absolutely nothing in West Greenwich. There’s an old boarded-up church and a graveyard, and when we arrive, a pickup truck.

In the graveyard, three high school aged boys are looking at gravestones. They say they are looking for the grave of Mercy Brown, the vampire.

… Her gravesite has become a Halloween favorite among vandals and spook-seekers. But these lads, all high school sophomores, are not interested in vandalism or history, or even vampires and the occult.

Explains Erik Johnson: “We want to bring girls down here and freak them out.”

Mercy Brown is buried in Exeter, at least 10 miles away.

Freaked out is precisely what several adult legend-trippers were on Halloween of 1993, as they poked around the Plain Meeting House cemetery. Two days later, the following account appeared in the Providence Journal:

Two couples out for pre-Halloween fun in a historical cemetery Friday night made a macabre discovery that has police baffled—a newly opened grave, with a body in an opened casket beside it.

State police say they don’t know who dug up the casket or what the motive was. They said nothing was missing from the casket.

… Theresa Safford, one of the four who found the casket, said the group had intended to visit a staged haunted house attraction in Coventry but arrived just after it closed.

Then they decided to visit the historical cemetery to look for the grave of someone, who, according to local legend, was a vampire.

As they were walking through the cemetery, under Friday night’s full moon, they stumbled upon the opened grave.

It shouldn’t take a police detective to figure out why the casket was dug up. Someone must have been looking for Nellie’s grave, which is unmarked. In the words of one of the legend trippers, “I was ready to pass out and die. It was a new grave. I started to hyperventilate.” Just the sort of thrill that legend trippers crave. I have no doubt that they have recounted their experiences to everyone they know, and that the sprouting variants of Nellie’s legend will bolster her supernatural status and add to the mystery of the Plain Meeting House Cemetery.

After reading about this incident, I contacted the State Police, requesting more information. I was told that someone would get back to me. (Perhaps that someone who never returned my call was engaged in conferring with the people who know the TFC—“teacher from Coventry.”) I asked an acquaintance who is a member of the West Greenwich fire and rescue department if he knew anything about the exhumation. He told me that the corpse had been buried only a few days before, and that the deceased had been an older man; my friend referred to him as a “town character.” He said that, given the coffins weight, it must have been dug up by several rather strong individuals.

Almost exactly two years after this illicit exhumation, I finally did receive some information from the State Police—but it was entirely accidental. I was in the Tillinghast family cemetery with a production crew from the Sightings television series for an on-location interview. Midnight was approaching, bright lights were illuminating the old gravestones, and a gasoline-driven generator used to power the lights, cameras, and—I hesitate to admit—fog machine, was humming, a bit too loudly for nearby neighbors. When a car with two state troopers pulled up, the producer suggested that I fill them in on what we were doing. I stifled the urge to ask, “Why me?” and approached the officers. After they were satisfied that we weren’t ghouls, cultists, or even just legend trippers, they relaxed. One of the troopers explained that they were being extra vigilant because someone had actually dug up a body a couple of Halloweens before in West Greenwich.

“Yes,” I said. “I read about it in the newspaper, and called the State Police and asked for more information. But no one would tell me anything.”

Somewhat apologetically, he said that they don’t like to publicize that kind of activity because of the “copycat” phenomenon. He told me that he was one of the officers called to the scene. The corpse was that of a local character, he said, and when they found him, he had a can of beer in one hand and a pack of cigarettes in the other. Then he added, “It was really weird. He had all this long hair and a beard. He looked like a werewolf.”

Under my breath, I muttered, “Oh, jeez.” I should have known that it was only a matter of time before a werewolf joined our local vampire.

American legend trippers looking for vampires are not limited to American cemeteries. Some U.S. soldiers in Kitzingen, Germany, became attracted to a cemetery because one of the gravestones is decorated with bats and skulls, the functional equivalent of the “I Am Waiting and Watching For You” inscription on Nellie’s grave. And, like the legend trippers at Nellie’s gravesite, the soldiers of the 3rd Infantry Division would not be deterred from their midnight vigil, even when confronted with rational thought. Despite the fact that Transylvania was seven hundred miles away, the American soldiers continued to gather at the site, waiting for Count Dracula to rise from the grave in search of his victims. One of the nontripping soldiers commented, “I don’t know if they really think they’ll see him, but when somebody is convinced, perhaps they can make it happen.” Like the local folks in West Greenwich, the mayor of Kitzingen realized his impotency in the face of belief: “You can’t stop these young fellows from believing what they want,” he said. Garlic may stop a vampire dead in its tracks, but nothing seems to ward off spellbound legend trippers.

Unrelenting vandalism is often the price paid by a cemetery that attains to legendary status. Gravestones are defaced, broken, and even stolen. While Everett Peck remained steadfast in his vigilant protection of Mercy Brown’s gravestone in the Chestnut Hill cemetery around Halloween, he was caught off guard in mid August in 1996. As the newspaper reported, “In 1892, they took her heart. In 1996, they’ve taken her gravestone.” It wasn’t the first time. For many years, the stone was unattached to its base, the separation a result of earlier vandalism. In this recent theft, the town offered a $50 reward for information leading to the recovery of the stone. Less than a week later, the gravestone was reported recovered (with no other details released to the public). Everett said, “There’s no damage to it. The recovery made my night. I slept for the first time in a long time.” Now, Mercy’s stone has a thick iron collar connecting it to its base.

Over the years, Nellie Vaughn’s gravestone has been knocked over, broken in two, then chipped away, piece-by-piece. Some have even attempted to excavate her grave. As a last-resort attempt to stem the vandalism, community members moved what remained of her gravestone to a safe, but publicly unrevealed, location. Naturally, the “disappearance” of Nellie’s gravestone has served only to heighten the mystery and reinforce her supernatural status.

Perhaps it’s time we—all of us, scholars, commentators, and legend trippers, alike—let Nellie Vaughn rest in peace. But I can’t leave this case without offering a tantalizing scrap of genealogy. While it does nothing to resolve Nellie’s status as a vampire, it does suggest that her community had access to firsthand knowledge of the tradition. From 1840 to 1878, the pastor of the Plain Meeting House Church was Reverend John Tillinghast, a second cousin of Stukeley Tillinghast, the father of Sarah, the vampire. The Tillinghast family is woven into the tapestry of New England vampire practice.