This one burial was really weird,” the voice at the other end of the phone was saying. “It looks like this guy was buried long enough to decompose, dug up, some of his parts were rearranged … and then he was buried again.” The voice belonged to Nick Bellantoni, Connecticut State Archaeologist. Nick said that he was aware of my research on the New England vampire tradition and thought that I might be able to shed some light on these peculiar findings in the town of Griswold, Connecticut. He told me that earlier in the year, 1990, three boys were having fun sliding down the slopes of a recently excavated section of a gravel pit about two miles from the village of Jewett City. As one of the boys descended, two human skulls seemed to fly out of the ground, accompanying the horrified youngster to the bottom of the pit. The boys reported their find to the local police, who, at first glance, wondered if there might be a serial killer in town. Closer scrutiny revealed that the remains were quite old, suggesting that the state archaeologist was a more suitable investigator than the medical examiner.

Nick Bellantoni’s on-site investigation indicated that the skulls came from a small, unmarked cemetery, which was being worn away by a privately operated sand-and-gravel mine. The partial remains of eight individuals had eroded out from the cliff. Nick told me that he and his crew had excavated the burials that were perched dangerously close the edge of the cliff and had begun research to determine who was interred in the cemetery. Since soil erosion was occurring at an alarming rate, and it was impossible to stabilize the bank, the landowner asked Nick to excavate the entire cemetery and reinter the remains in another location. Nick told me that they were seeking funding to proceed with the excavations. Forensic anthropologist Paul Sledzik, Curator of Anatomical Collections at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington, D.C. (and a Rhode Island native), also had been invited to assist in the investigation. My interest rose with each revelation. When Nick said that he would contact me when work resumed so that I could visit the site, I practically had one foot out of the door.

A check of the map revealed that Griswold’s primary village was Jewett City, the home of Horace Ray. After nearly a decade of frustration, I was again on the trail of the Ray family vampire. Montague Summers had written that Horace Ray died of consumption in 1846 or 1847, and that two of his three sons followed him to the grave, the last in 1852. According to Summers, when the third son showed the signs of consumption, the bodies of his two brothers were exhumed and “burned on the spot.” But Summers led me astray with his remark that the event, as reported in the Norwich Courier, took place on June 8, 1854. Believing that it would be a simple matter to find the newspaper article, in the summer of 1983, I drove to the Connecticut State Library and Archives in Hartford. I encountered a minor complication as I checked the newspaper index. There were two versions of the Norwich Courier, a weekly edition that appeared each Wednesday and a “daily” edition that was published on Tuesdays, Thursdays, and Saturdays. (I can’t explain it either; even if you combine the weekly and daily editions, you still end up with just four publications a week—not my idea of daily.) This should be easy, I thought, plunking down in front of the microfilm reader. Several hours and a major headache later, I was back where I started. Having checked every daily and weekly issue from June, 1854, through the end of 1855, I found nothing. No vampire. No exhumation. No burning corpses. No “horrible superstition.”

Hoping that a change of venue would lift my spirits, if not cure my microfilm headache, I strolled to the State Archives of History and Genealogy. During the Depression, in one of their WPA projects, the state of Connecticut had paid researchers to visit every cemetery in the state and record the headstone inscriptions. Flipping through the 3x5 cards was a welcome relief from the whirling vertigo of the microfilm reader. I did not find a Horace Ray who fit the time and place provided by Summers, but there was a card for an Elisha H. Ray, who died at the age of 26 in 1851 and was buried in old Jewett City cemetery. Could Elisha have been one of the two sons whose bodies were exhumed and burned?

I seemed to have hit a dead end. Then, after our phone conversation, Nick Bellantoni sent me a photocopy of the “missing” Norwich Courier article. Working back through recent sources, he had found that the article appeared in the May 24, 1854 edition of the Norwich Weekly Courier under the headline, “Strange Superstition.” The article states that the bodies were exhumed on May 8, not June 8—a small error that had created a lengthy stalemate.

A strange and almost incredible tale of superstition has been related to us of a scene recently enacted at Jewett City. It seems that about eight years ago, a citizen of Griswold, named HORACE RAY, died of consumption. Since that time, two of his children—both of them sons, we believe, and grown to man’s estate—have sickened and died of the same disease, the last one dying some two years since. Not long ago, the same fatal disease seized upon another son, whereupon it was determined to exhume the bodies of the two brothers already dead, and burn them. And for what reason do our readers imagine? Because the dead were supposed to feed upon the living, and that so long as the dead body in the grave remained in a state of decomposition, either wholly or in part, the surviving members of the family must continue to furnish the sustenance on which the dead body fed. Acting under the influence of this strange, and to us hitherto unheard of, superstition, the family and friends of the deceased, accompanied by various others, proceeded to the burial ground at Jewett City, on the 8th inst., dug up the bodies of the deceased brothers, and burned them on the spot. The scene, as described to us, must have been revolting in the extreme; and the idea that it could have grown out of a belief such as we have referred to, tasks human credulity. We seem to have been transported back to the darkest age of unreasoning ignorance and blind superstition, instead of living in the 19th century, and in a State calling itself enlightened and christian [sic].

One of the recent articles that Nick had found appeared in the Norwich Bulletin on Halloween of 1976. The author’s research indicated that the father probably was Henry B. Ray, not Horace Ray. The first member of the family to die was Lemuel Billings Ray, the second eldest son. According to his tombstone, he died in March, 1845 at the age of twenty-four. Four years later, the father expired. In 1851, the twenty-six-year-old son, Elisha H., died. Two sons remained: James Leonard, who lived until 1894, and Henry Nelson who, according to town hall records, was born in 1819. The author was unable to locate either a death record or tombstone for Henry Nelson, concluding that “the plight of the young man in whose behalf the family must have undergone such horrors” was unknown.

The other recent source provided by Nick also asserted that there was no documentation of Henry Nelson’s death. “Unfortunately,” David E. Philips wrote in Legendary Connecticut,

there is neither a gravestone nor any document to confirm the date of Henry Nelson Ray’s death. But since there is a date of death (either on a marker in the Jewett City Cemetery or in the Griswold town records) recorded for all other members of the family, it is entirely probable that Henry Nelson survived his “fatal” illness of 1854. The young man who caused his family’s vampire panic may well have lived to a ripe old age. If so, the surviving Rays were undoubtedly convinced that their anti-vampire “medicine” had saved his life.

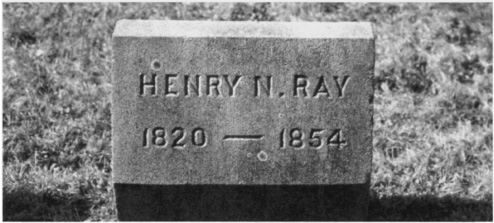

Gravestone of Henry N. Ray, Jewett City Cemetery, Griswold, Connecticut. The bodies of two of Henry’s brothers were exhumed on May 8, 1854, and burned in the hope of saving Henry’s life. Courtesy of Michael E. Bell.

As I write these words, I am looking at the two photographs of Henry N. Ray’s headstone that I took ten years apart. Philips probably did not find Henry N.’s gravestone for the same reason that I couldn’t find the rest of the Rays. We both expected the family stones to be close together, in the typical New England pattern. He found the father, the mother and, except for Henry Nelson, the children. I found Henry Nelson, and was baffled by the absence of the others. It was actually very easy for me to locate Henry Nelson’s gravestone, since it was in a newer section of the cemetery, just inside the main gate. The small, plain granite gravestone, with a low profile, appears too modern to have been made in the mid—nineteenth century. The inscription reads simply, “Henry N. Ray / 1820-1854”. It took several visits to the cemetery and a phone call to Mary Deveau of the Griswold Historical Society before I finally found the headstones of the rest of the family. They are grouped together in the oldest part of the cemetery, which is tucked away out of sight. Mary said that many of the Ray family graves, including Henry Nelson’s, were moved in the early 1900s, which explains the newer-looking stone. Town records indicate that Henry N. was born in 1819, while the gravestone lists 1820. Such discrepancies, especially when stones are replaced long after death, are not uncommon. If Henry N., who died in 1854, was indeed the consumptive son, the ritual apparently did not work for him. When Mary showed me documentation that Henry N.’s young wife and children also died of consumption, that conclusion seemed sadly accurate.

A few weeks after our initial conversation, Nick Bellantoni gave me an update on the cemetery investigation at Griswold. In 1690, a couple from Boston, Nathaniel and Margaret Walton, established a farm in the northwest corner of Griswold (which was part of the town of Preston until 1815). The eldest of their five sons, John, became a Congregational minister, known in the region as “John the Scholar.” Their second son, Nathaniel, and his wife, Jemima, remained on the family farm. In 1757, Nathaniel purchased a plot of land from a neighbor for use as a family burial ground. The cemetery was active until the early 1800s, when the members of the Walton family began a westward trek in search of better farm land. The cemetery continued to be used by another, unidentified family until about 1830, after which it was abandoned. The uninscribed fieldstone markers eventually were reclaimed by the land, and the Walton Family Cemetery faded from memory until its dramatic rediscovery in November, 1990.

Nick also sent me a reference to yet another vampire incident in Connecticut. This one was reported in 1888 by J. R. Cole, in his History of Tolland County, Connecticut:

In the old West Stafford grave yard the tragedy of exhuming a dead body and burning the heart and lungs was once enacted—a weird night scene. Of a family consisting of six sisters, five had died in rapid succession of galloping consumption. The old superstition in such cases is that the vital organs of the dead still retain a certain flicker of vitality and by some strange process absorb the vital forces of the living, and they quote in evidence apocryphal instances wherein exhumation has revealed a heart and lungs still fresh and living, encased in rottening and slimy integuments, and in which, after burning these portions of the defunct, a living relative, else doomed and hastening to the grave, has suddenly and miraculously recovered. The ceremony of cremation of the vitals of the dead must be conducted at night by a single individual and at the open grave in order that the results may be decisive. In 1872, the Boston Health Board Reports describe a case in which such a midnight cremation was actually performed during that year.

The report doesn’t actually describe what took place in the cemetery that night. Were all five sisters disinterred and their corpses examined to find the one with “fresh and living” heart and lungs? Or did they burn the organs of all five? The stipulation that the ceremony had to be carried out by a single individual, at night, was striking, unlike any other case I had encountered. The term “vampire” is never mentioned.

I checked every gravestone in the old cemetery in West Stafford several years later and found no evidence of five sisters dying in rapid succession. There are four possible explanations: their stones are among those that are illegible or missing; they were buried in unmarked graves; one (or more) of the sisters was married and interred under a different surname; or, they were buried in another cemetery, such as the Universalist cemetery just down the road, dating from about 1799.

I had made several half-hearted attempts to find the Boston Health Board Reports that, in 1872, according to Cole, described “a midnight cremation”—in Boston, I assumed. Then, in the Summer of 2000, with the assistance of the Internet to narrow down potential sources, I launched an all-out effort. My personal odyssey of July 24, 2000, exemplifies both the frustrations as well as the small, unforeseen triumphs of following the vampire trail. I left on the 8:13 A.M. train from Providence, almost trembling at the prospect of finding a vampire exhumation in Boston. None had yet been documented in a city. My destination was the Massachusetts State Library, to examine an 1872 publication entitled, Third Annual Report of the Board of Health, Massachusetts. Scanning the table of contents, I found nothing that would seem to point to consumption and curative measures, nor any red-flag terms such as “superstition.” I plowed through the 300-odd pages, knowing it was probably a futile exercise.

With mounting desperation, I turned to “consumption” in the card catalogue. There was a small sign on both large banks of the card catalogue informing patrons that works prior to 1975 were in the catalogue. All later issues were to be found in the electronic database. I was thinking that the card catalogue would soon join vampire exhumations and consumption as antiquated curiosities when I was shaken from my state of suspended animation. There was a cross reference on the consumption card. Since the researcher was directed to “see Tuberculosis,” I concluded that this entry dated from the late nineteenth century. (I wondered, were there ever cards under a subject head of “Consumption”?) I found two intriguing entries, both authored by a Dr. Henry I. Bowditch. One title suggested that Dr. Bowditch adhered to a theory that consumption was the result of geography and topography.

It was lunch time, and since I had no faith that Bowditch would mention, much less discuss, folk cures for consumption, I took the T to South Station, intending to head back to Providence. I was annoyed to see that I had missed a train by fifteen minutes and would have to wait more than three hours for the next one. I debated whether to browse Borders Bookstore and Tower Records or try my luck with Bowditch. Bowditch won by circumstance. Walking in the direction I supposed Tower Records to be, I emerged onto the Commons and found myself just across the street from the State House. I took this as an omen and went, with confidence, back into the State Library.

The librarian told me that the two Bowditch works were in Special Collections. (“Special Collections”—I’m apprehensive, if not downright queasy, at the thought. Will I measure up? Are my hands and fingernails clean? Are my needs sufficiently pressing?) I recovered from this moment of self-doubt in time to hear the librarian giving me directions from the third floor to the basement home of Special Collections. Apparently, I missed an important instruction and took the wrong elevator, for I emerged into a basement cul-de-sac housing some state agency not remotely connected to libraries or books. I was informed by two passersby that, yes, they had heard of Special Collections, but that, no, I couldn’t get there from here (not without going back up to the first floor, then crossing over from the east wing to the west and, from there, going back down to the basement). I managed to accomplish this task with only one more stop for directions.

When I finally arrived at Special Collections, the door was locked. A small computer-generated sign read, “Will be right back. Please wait.” OK, why not? I sat in a chair placed conveniently next to the door, under a bulletin board with all sorts of “inspiring” notices. The chair looked worn and the seat cushion was stained. I sagely concluded that Special Collections was understaffed and not generously funded. The librarian really did come right back though, and she proved helpful and sympathetic (I didn’t much mind having to put “anything you don’t need”—that is, everything but a pencil and notebook—into an ancient wardrobe).

I first checked Bowditch’s “pamphlet” on the geographic correlations of consumption. The frontispiece was headed, “Boston Board of Health, 1872,” which sent my pulse racing. It was back down to 60 bpm by the time I finished skimming Bowditch’s transcribed speech to the Boston Board of Health. His bottom-line argument was that living in damp, perhaps especially cold and damp, places was the major cause of consumption. I perused pages of testimony and statistical correlations mustered to demonstrate Bowditch’s “law.” There were many case histories, mostly sad, of entire families being decimated, with a few bright spots (such as the family member who was spared because he spent most of his time at sea, away from the boggy farm). Among all of the anecdotal evidence, I found not one reference to exhumations, vital organ burning or any of the other morsels I sought. Certainly, no “midnight cremation.” I was doubting my premonition that missing the train and bumping into the library was a sign that I would find the missing puzzle piece.

But I still had to review the pamphlet, Consumption in New England. A few sentences into the manuscript, I had the eerie feeling that I had been there before. Comparing the two manuscripts side-by-side revealed that Bowditch’s address to the health board had been transcribed and published under two different titles (I stifled the thought that Dr. Bowditch had padded his resume). Just to be sure, I flipped through the pages again. My eye somehow caught the word, “disinterred,” and I paused to read a passage I had missed the first time. A Dr. J. L. Allen, of Saco, Maine, had been one of Bowditch’s correspondents who had provided data regarding their cases of consumption and how they correlated to geography. Bowditch wrote that Dr. Allen, “a practitioner of long standing,” had noticed two ridges of land that were identical in every respect save for the amount of moisture in the soil.

Almost every family has been decimated on the wet part, while almost all upon the dry portion have escaped…. One ridge is quite dry, the other is literally filled with springs. Nowhere can a spade be driven a few feet into the ground, without meeting water. In fact, in former times, the superstitious frequently had their friends, who had died of consumption, disinterred, and Dr. Allen invariably found the coffins filled with water, however shallow may have been the graves.

While this brief passage does not refer to any specific instance that might be investigated, and does not provide specifics regarding what procedures were followed after disinterment, it does suggest that vampires were being sought in Maine in the early nineteenth century. And, perhaps equally intriguing, it seems to imply that a medical doctor, Dr. Allen himself, was routinely present at the exhumations. I didn’t find the Board of Health Report I was looking for, but the trip to Boston was amply rewarded. Dr. Rational has no explanation for omens (or hunches, if you prefer), yet he cannot disregard them.

I continued to search for the 1872 Boston Board of Health Report and was successful at the Archives of the City of Boston, which contained the Annual Reports of the Boston Board of Health, spanning the years from 1872 to 1880, as well as the document that established the Board of Health in 1872. Alas, I found nothing remotely related to the vampire practice. But the latter document did promulgate regulations on the interment of the dead. The following passages suggest why the Board of Health might have been aware of, and perhaps reported on, a vampire incident: “No person shall remove any dead body, or the remains of any such body, from any of the graves or tombs in this city, or shall disturb any dead body in any tomb or grave without the license of the Board of Health or the City Council.… No grave or tomb shall be opened from the first day of June to the first day of October, except for the purpose of interring the dead, without the special permission of the Board of Health.” The reference to obtaining the permission of the City Council led me to go through their minutes, too. Again, nothing. The trail towards Boston’s “midnight cremation” still beckoned.

As I drove to Griswold, Connecticut (about ten miles west of the Rhode Island state line, bordering West Greenwich and Exeter), I mulled over the evidence provided by Nick Bellantoni. When I arrived at the site, Nick and two assistants were in the final stages of the excavation. Several skeletons lay exposed in their opened graves. A young woman with a clipboard was sitting cross-legged on the ground next to Burial 20, sketching the locations of the bones of a nearly complete skeleton of a man in his early thirties. Almost all of the twenty-seven whole or partial skeletons had already been placed in acid-free tissue and bubble wrap and transported to the Archaeological Laboratory at the University of Connecticut for storage, awaiting their reinterment in the nearby historic Hopewell Cemetery.

One exception was Burial 4, the “weird” one that Nick had mentioned on the phone, which had been sent to the Museum of Health and Science for analysis by Paul Sledzik. The complete skeleton of this man, the best preserved of the cemetery, had been buried in a crypt with stone slabs lining the sides and top of the coffin. On the lid of the hexagonal, wooden coffin, an arrangement of brass tacks spelled out “JB-55,” presumably the initials and age at death of this individual. When the grave was opened, JB’s skull and thighbones were found in a “skull and crossbones” pattern on top of his ribs and vertebrae, which were also rearranged.

Excavated grave of JB, Walton Family Cemetery, Griswold, Connecticut. Long after decomposition, JB’s body was exhumed and some of his bones were rearranged, perhaps as an attempt to keep him from leaving his grave. Courtesy of Connecticut State Museum of Natural History.

Two adjacent burials appeared to be related to JB One, a 45-to 55-year-old woman, had “IB-45” spelled out in tacks on her coffin lid and the other, a child, aged 13 to 14, had “NB-13” on his/her coffin. The layout of the cemetery indicated that people had been buried in clusters as opposed to the typical well-ordered rows. The seven closely spaced graves in the northern cluster were of small children, suggesting a disease epidemic within the family or community. In fact, about half of those buried in the cemetery never reached their teens. Death records from the nearby town of Norwich show that there was a measles epidemic in 1759 and a smallpox epidemic in 1790, either of which could be represented in this cemetery. An 1801 account in a history of Griswold states that, twenty-five years earlier, “consumptions … proved to be mortal to a number” of people.

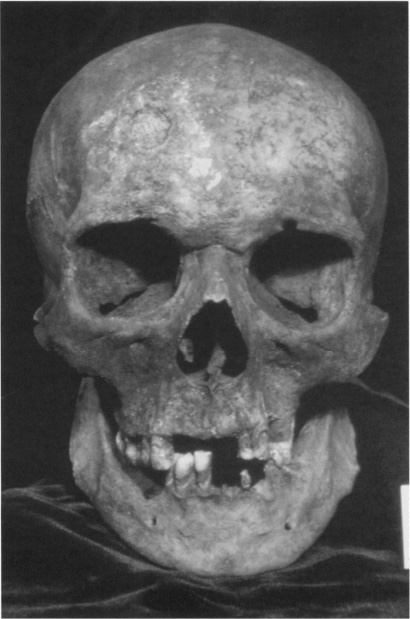

Skull of JB. He is probably the only suspected American vampire whose remains have been studied by scientists. Courtesy of the National Museum of Health and Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology, Washington, D.C.

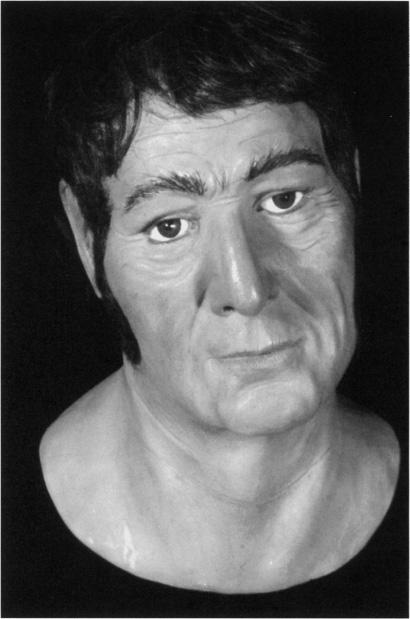

In light of the biomedical evidence uncovered, JB must have been an imposing figure. Rugged and tall, at six feet, he probably walked with a limp, due to severe osteoarthristis of the left knee, and hunched over, from a healed fracture of his right collarbone that was never set. Surely he was in pain, not only from the arthritis, but also because of chronic dental disease. Examination of JB’s remains also revealed lesions of the second, third, and fourth ribs, indicating chronic respiratory disease, most likely pulmonary tuberculosis, but possibly some other disease, such as typhoid, syphilis, or pleuritis. In any event, J.B.’s condition probably would have been interpreted as consumption, as Nick and Paul subsequently observed:

Regardless of the specific infectious etiology of pulmonary disease in this individual, symptoms of a chronic pulmonary infection severe enough to produce rib lesions would have probably included coughing, expectoration of mucous [sic], and aches and pains of the chest. Such symptoms, if not actually caused by pulmonary tuberculosis, would likely have been interpreted as consumption by 19th century rural New Englanders.

No other cases of tuberculosis could be discerned in the excavated skeletons. Paul and Nick concluded that “the physical arrangement of the skeletal remains in the grave indicate that no soft tissues were present at the time of rearrangement, which may have been 5 to 10 years after death. No other burial had been so desecrated at the cemetery.”

JB’s decapitation and the rearrangement of his leg bones led me back to the story of the “Welsh wizard” that appeared in Witchcraft in Old and New England (quoted in Chapter 3). After his death, the wizard kept coming back to terrorize his neighbors until, finally, “a brave English knight” had his body dug up and beheaded. Was this a common approach to keeping a corpse from returning to bother the living? Did it have a precedent in the ancestral regions of New England, in northern Europe, especially Great Britain? It became clear as I researched these questions that what had been done to JB’s corpse was far from a unique occurence.

Archaeological evidence indicates that this practice goes back at least to the Iron Age, more than three thousand years ago. A number of Celtic sites show similar ways to deal with apparently dangerous corpses, including “tying the body, prone burial, displacing parts of the skeleton, partial cremation.” At one burial site, nearly half of the eighty skeletons were missing the skull, and there were “others in which the skull was present but separated from the trunk.” Many of these graves had been reopened after burial. British archaeologists who discovered late Roman-British and pagan Anglo-Saxon cemeteries, dating from the third to the seventh centuries, containing corpses that had been decapitated, concluded that such burials were not uncommon. Their excavations disclosed that the detached head was normally positioned towards the lower end of the corpse, most often between or next to the lower legs or feet. But skulls have been found on or beside the pelvis, on the chest, by the arms, and near the neck. In one of the burials, the head had been removed and placed between the thighs, and the lower legs had been cut off and buried beside the upper arms. In most of these cases, there is no evidence showing whether decapitation was the cause of death or occurred after death. The same archaeologists also found the earliest recorded case of tuberculosis in Britain—an adult woman with a possible case of spinal tuberculosis (or Pott’s disease). Several of her vertebrae were affected and the condition was diagnosed as “long-standing and … almost certainly due to healed tuberculosis.” No decapitations were found at this cemetery.

The archaeological record does not provide explicit answers regarding why such measures were undertaken. For that, we must turn to written history. A medieval historian wrote about a raging pestilence that was attributed to the ghost of a man killed shortly before the onslaught of the misfortune. “To remedy the evil they dug up his body, cut off the head and ran a sharp stake through the breast of the corpse. The remedy proved effectual, for the plague ceased.” Employing more than one method, in this case decapitation and staking, is not unusual. Murderers whose spirits were feared and those thought to be vampires might receive the same treatment. In 1591, a German shoemaker of Breslau, a suicide, was suspected of being a vampire. His body was exhumed, “then its head was cut off, it hands and feet dismembered, after which the back was cut open and the heart taken out.” A German source of 1835 noted the following:

In East Prussia when a person is believed to be suffering from the attacks of a vampire and suspicion falls on the ghost of somebody who died lately, the only remedy is thought to be for the family of the deceased to go to his grave, dig up his body, behead it and place the head between the legs of the corpse. If blood flows from the severed head the man was certainly a vampire, and the family must drink of the flowing blood, thus recovering the blood which had been sucked from their living bodies by the vampire. Thus the vampire is paid out in kind.

The telltale presence of flowing blood fits snugly with the New England tradition of seeking “fresh” blood in the suspected vampire’s heart. And here we have an explicit explanation for drinking the vampire’s blood. Ingesting the ashes of the burned heart seems but one step removed.

The simplest rationale for the practice of decapitation is that

“the soul was believed to reside in the head, so that the removal of the latter ensured the complete and final separation of the soul from the body. The placing of the head by the legs may have been intended as a reminder to the soul that it was now time to set off on its journey, for which it could no longer use its bodily legs—as was often emphasized by placing boots elsewhere in the grave.”

The same scholar speculated that decapitation might “liberate the spirit and remove any fear of haunting.”

In much closer proximity to JB and Connecticut is “a strange Russian story,” collected in upstate New York in the early 1940s, that related the “digging up the corpse of a very active ghost, cutting the head off the corpse and putting it between his legs and then reburying him” to keep him from returning from the grave. Given the firmly established precedents in northern Europe—and at least one bit of evidence suggesting it was known, if only through narrative, in New England—it does not seem extraordinary that the practice would make an appearance in Connecticut.

After my visit to the site, Nick Bellantoni, Paul Sledzik, and I conferred. Combining our experiences in archaeology, physical anthropology, history, and folklore, the best conclusion we could reach was that JB had been exhumed to counteract the spread of tuberculosis. Here, in short, was the first truly tangible, physical evidence for the vampire tradition in America. If we could see into the grave of one of these vampires, what would we expect to find? Probably a skeleton that would have

1) been disrupted after death;

2) shown evidence of tuberculosis; and

3) been found in a cemetery from the same time and place as other New England vampire accounts.

JB fit these three criteria, and no other interpretation of his unusual remains even approached the coherence of the following scenario: An adult male, JB, died of pulmonary tuberculosis or a similar infection interpreted as tuberculosis by his family. Several years after the burial, one or more of his family members contracted the disease, including, possibly, his 45-year-old wife, IB, and his 13-year-old son or daughter, NB. As a last resort—to spare the lives of the family and stop consumption from spreading into the community—JB’s body was exhumed so that his heart could be burned. When his body was unearthed, however, JB was found to be in an advanced stage of decomposition. Perhaps his ribs and vertebrae were in disarray as a result of the desperate search for the remains of his heart. Finding no heart, JB’s skull and thighbones were arranged in a “skull and crossbones” pattern.

It was not difficult to explain the presence of the vampire tradition in Eastern Connecticut. Not only does it border on Rhode Island’s South County—a hotbed of vampire activity, as we have seen—it also shares a common ethnic heritage, dialect, and other customs. Indeed, the town of Griswold was “partly settled” by emigrants from South County in the early 1800s. A town historian described these Rhode Islanders as “profane and uneducated,” writing that “their clownish manners and their lack of schools were all objects of ridicule and contempt. They were accounted ignorant and vicious.”

The discovery of the Walton family cemetery, and the moderate amount of media attention given its excavation, has led to the creation of at least three works of fiction: a novel, a short story, and a poem. If you knew about JB, the opening paragraph of the young adult novel, The Apprenticeship of Lucas Whitaker, might send shivers down your spine:

The Connecticut countryside, 1849

The grave was dug. Carefully, Lucas Whitaker hammered small metal tacks into the top of the coffin lid to form his mother’s initials: HW, for Hannah Whitaker. Then he stood up to straighten his tired back. All that was left was to lower the pine box into the cold, hard ground and cover it with dirt.

It is more than coincidence that this passage recalls the Walton family cemetery in Griswold. The author, Cynthia DeFelice, had read several newspaper articles that summarized the discovery of JB and the interpretations offered by Nick, Paul, and me. In her foreword, she acknowledges the factual basis for her fictional narrative, which, for the most part, treats the vampire superstition with sympathetic understanding.

Fleeing the farm that embraces the remains of his entire family, dead of consumption, the young Lucas wanders aimlessly through the Connecticut countryside until he answers a “help wanted” sign in the fictional town of Southwick. As an apprentice to Doc Beecher, Lucas is introduced into both the wonders and limitations of medicine in the middle of the nineteenth century. When Doc admits that he is helpless in the face of consumption, Lucas asks why he doesn’t use the “cure” that he, Lucas, had learned of too late to save his own family.

“I didn’t really understand the cure, how it worked. But now I do, thanks to you.”

Doc appeared startled. “How’s that Lucas?”

Lucas was surprised by Doc’s question. “Well, you said—you said—lots of things. You said doctors don’t always know what to do.”

Doc smiled bleakly. “True enough.”

“And you said that old witch woman—”

“Moll Garfield?”

“Yes. You said she knows a lot even though people call her a witch, and if she used hair from a dog that bit you it might cure the bite. And you told me how you can protect yourself from getting smallpox real bad by making sure you get just a little bit of it. So, when I thought about the cure, the one Mr. Stukeley did…”

“Yes?”

“Well, it seemed the same.”

Lucas explains how breathing the smoke of the burning heart and making medicine from the ashes seemed just like an inoculation. And that removing the heart was sort of like bleeding people to get the bad blood out or cutting off a person’s festered leg because it was making the rest of him sick. And then, as if to explain his own involvement with the “cure,” Lucas continued. “Remember you said that sometimes you think the good of what you do isn’t in what you do so much as in the—the kindness you show in doing it?”

As Lucas works through his own understanding of the relative merits of medical science versus folk practices, the reader is given a reasonably accurate depiction of life, disease, and death in rural nineteenth-century New England. There are some familiar names, including a Sarah Stukeley, and even an Everett Peck! And, not surprisingly, Lucas’s neighbors had learned the “cure” from their Rhode Island relatives. One of DeFelice’s sources probably was an article that appeared in the Washington Post around Halloween of 1993, in which my explanation for the “cure” is quoted:

“It is sort of homeopathic magic, like taking the hair of the dog that bit you,” said Bell. “It’s what an inoculation is, and in that sense is not that far removed from current scientific thinking.”

Paul Sledzik coauthored, with mystery writer Jan Burke, a short story that centers around a vamp ire scare in a fictional Rhode Island village. In “The Haunting of Carrick Hollow,” the narrator, Dr. John Arden, returns home after medical school to set up his new practice. He has occasion to recall tragic events that had occurred five years previously, in 1892, when he left school to attend to his family’s consumption crisis. His younger brother, Nathan, was ill, and his father, Amos, an apple farmer, seemed haggard.

“Half my orchard has been felled,” he remarked, and I knew he was not talking of the trees, but of the toll consumption had taken on his family. “First Rebecca, then Robert and Daniel. Last month, your mother—dearest Sarah!…”

“Noah and I are healthy,” I replied, trying to keep his spirits up. “And Julia is with her husband in Peacedale. She’s well.”

Two days before he died, Daniel told John that he had dreamt that Rebecca and Robert came into his room and sat on his bed. Now, Nathan was worried that his own dead mother would come for him, because he had heard the tales of Mr. Winston, who had been telling everyone in the village that consumption was caused by vampires.

When John seemed incredulous that anyone would believe such things, his father answered, “In the absence of any cure, do you blame them for grasping at any explanation offered to them? Grief and fear will lead men to strange ways, Johnny, and Winston can persuade like the devil himself!”

The Winston character, who plays the role of belief specialist, is not at all likable. Wealthy and conniving, he attempts to force others to go along with his demand to exhume the dead. In his speech before a town meeting, Winston says,

“I have great sympathy for my neighbor, Amos Arden. The death of his wife and three children is a terrible loss for him. But in consumption, the living are food for the dead, and we must think of the living! The graves must be opened, and the bodies examined! If none of their hearts is found to hold blood, we may all be at peace, knowing that none are vampires. But if there is a vampire coming to us from the Arden graves, the ritual must be performed! This is our only recourse.” The room fell silent. No one rose to speak, but many heads nodded in agreement.

Arden bows to the pressure, but asserts that no one but him will touch his wife. He explains to his son, “I don’t do this because I believe it will cure consumption. But it is a cure for mistrust. A bitter remedy, but a necessary one.” Adding to the anguish, the elderly town doctor pronounces Nathan’s condition “hopeless.”

The description of the exhumed corpses is gruesomely accurate, as would be expected with Paul, a forensic anthropologist, as coauthor. The sons and daughter were mummified, with “dry skin stretched tight over their bony frames.” But the mother, who had been buried only three cold months, appeared “remarkably like the day we buried her.… Her nails and hair appeared longer, and in places, her skin had turned reddish.” Of course, “fresh” blood was found in her heart, and it was dropped into the nearby fire. Returning home, John and his father find the dead Nathan cradled in the arms of his brother, Noah.

At medical school, John Arden learns that the condition of his mother’s corpse was not unusual. And he learns about tuberculosis, too. Returning to his hometown, he visits the older town doctor, who gives him some advice: “Remember, John, that folks here are quite independent, even when it comes to medicine. They take care of their own problems, using the same remedies their grandparents used. It’s hard to fight their traditions.” Arden takes a special interest in treating tuberculosis and finally is able to convince his fellow citizens that medical science, not superstition, ultimately holds the best course of treatment. Angry that they had been persuaded by Winston to desecrate the bodies of their loved ones, the villagers give Winston a fitting reward.

Paul Sledzik’s knowledge of New England’s vampire tradition is apparent throughout the story, as we encounter a blending of now-familiar motifs from the cases of Mercy Brown and Sarah Tillinghast. Amos complained that half of his orchard, that is, half of his children, had died, just as in Snuffy Stukeley’s dream. Night visits by the deceased augured impending death. Buried only from January to March, 1892, the body of Sarah was exhumed and found to be in an apparently remarkable state. And the venerable doctor’s grasp of the townspeople echoes Everett Peck’s characterization of his own forebears: they were independent people who took care of their own problems. A significant difference between the tradition and the story probably is explainable in terms of the narrative’s need for an antagonist: Winston is consummately evil, whereas his counter-part in actual communities was more than likely genuinely attempting to help his neighbors. And, of course, the actual folks did not use (perhaps did not even know) the term “vampire.”

Inspired by an article in the New York Times that summarized both the discovery of JB’s remains and the Ray family incident, Michael J. Bielawa, a poet and librarian in Connecticut, composed “The Griswold Vampire.”

A good February fog

is a wonderful thing to be with

in the Connecticut woods.

Until you hear the stories told, down at the one pump station.

Always a warning as much as an invitation,

The old men will grin and spit…

“At night, Don’t be found on the cemetery road.”

The route inevitably changes.

And the wind will whisper something very old,

‘Why can’t they pass, and leave it alone

that crumbling gate

where trees lean away from the sleepless stones.’

But no. The living will always arrive, never on time,

looking for the Griswold vampire.

Beyond the wall,

Amidst the frozen wind-piled leaves

A member of the historical society

rubbed his muddied knee

rising from realigning a stone …

“Never strangers true vampires be,” he said,

“the loved ones they knew

upon whom they’d have to feed.

Demon lust for their family still living,

old Yankees did believe.”

The car moves on.

These visitors will forget, and the New England stories soon wither forgotten;

But as the strangers wave good-by

to the ancient guide who stands at the gate

waiting…

The driver laughs with his friends

and unnoticed,

the rear view mirror cradles no reflection.

The finding of JB’s grave still seemed incredible to me. Nick Bellantoni said that, as far as he could determine, the Walton cemetery was the first Colonial farm family cemetery ever excavated. What are the odds that it would hold a vampire?

A reconstruction of JB’s head made from his skull by forensic artist Sharon Long. Courtesy of the National Museum of Health and Medicine, Armed Forces Institute of Pathology Washington, D. C.