Greg Pronevitz

To understand the consortial landscape, the authors of this book conducted research in 2012 and looked at existing studies. They sent an online survey, Library Consortia in the 21st Century, to several e-mail lists used by library consortia personnel to gather data. The survey is referred to as “our 2012 survey” or “our survey” to differentiate it from a 2012 OCLC survey noted later in the chapter. The authors were particularly interested in the effect of the 2007–2009 Great Recession, the challenges presented during and after the subsequent slow recovery, and the variety of services provided by consortia. Responses from 77 library consortia were tabulated. The focus of this chapter is on the 66 responses received from consortia in the United States.

Membership in the 66 responding US consortia comprises more than 18,000 libraries. Sixty of those consortia reported budget figures; the aggregate of those exceeds $170 million per year.

In 2007, 240 library consortia were identified in the comprehensive survey Library Networks, Cooperatives and Consortia: A National Survey, by Denise M. Davis of the Office of Research and Statistics at the ALA. This study was supported with funding from the Institute for Museum and Library Services, enabling researchers to track down non-respondents and tabulate large data sets. The authors of this book found that 190 of the original 240 consortia still exist, though some as merged organizations. This analysis indicated that 50 consortia, or about 21 percent, are no longer operating.

Sixty-six US consortia responded to our 2012 survey, including 28 new consortia that were not included in the 190 mentioned above. Mergers and closings of consortia since 2008 were driven by two major factors that resulted in an overall reduction of 65 known consortia nationwide. The economic crisis brought on reductions in state funding of regional systems, leading to numerous mergers and closures in California, Illinois, Massachusetts, New Jersey, and Texas. The realignment of OCLC services and network support was the second major factor leading to seven service providers merging into others or closing.

Mergers accounted for the closings of five regional library systems in Massachusetts and the renaming of the sixth as a statewide organization, the Massachusetts Library System. Similarly, four regional library systems in New Jersey became LibraryLinkNJ. In Illinois, nine systems were merged into two, while in California fifteen consortia were merged into eight. In Texas only two of ten regional library systems are still in operation.

A number of former OCLC service provider networks are also no longer in operation. NEBASE in Nebraska merged with BCR, a mountain states service provider, BCR subsequently closed. NYLINK in New York also closed. NELINET in New England, Pennsylvania’s PALINET, and SOLINET in the southeast merged to form LYRASIS. Indiana’s INCOLSA and the Michigan Library Consortium merged to form the Midwest Collaborative for Library Services. MLNC in Missouri merged into Amigos Library Services in the Southwest. Amigos also took on work formally done by some of the closed Texas regional library systems. Two other OCLC-related groups that were included on the ALA list became part of OCLC itself. The new merged OCLC service networks continue to provide some OCLC services as well as other services to thousands of libraries. ILLINET (Illinois), Minitex (Minnesota and the Dakotas), OHIONET, FEDLINK (federal libraries), and WiLS (Wisconsin) also continued to provide some OCLC services.

There is variation in how members were counted. The largest consortia reporting is MINITEX with 4,250 participating libraries, and the smallest is the BC Electronic Library Network with two libraries. The average membership is 236, and the median membership is 53. The average staffing level is 9.6 full-time equivalents (FTEs) with a median staffing of about six. Staff with an MLS or equivalent average is 4.1 FTE; other professional staff averages 3.4 FTE. The average annual budget is $2.8 million with a median budget of $1.2 million. Responses were received from 31 states. The state with the highest participation rate was Massachusetts, with six consortia responding. Three states—California, New York, and Ohio—each had five consortia responding. The remaining responses included no more than three consortia per state.

To understand the effects of the economic downturn, our 2012 survey asked an open-ended question: “Has your consortium undergone any major changes since 2007 such as a merger, serious cutback, membership decline, or closure?” The most common major change reported was budget reductions. A total of 22, or 33 percent, of respondents noted budget reductions. On the other hand, two consortia noted budget increases.

Surprisingly, 16 respondents (24 percent) reported the major change was an increase in membership. Looking deeper into the explanations provided by some respondents, we found that these membership increases occurred because new libraries join consortia either to take advantage of online content discount programs or to join shared integrated library systems. Two consortia noted that they gained members when a nearby consortium closed or merged. It is also interesting to note that five consortia mentioned a membership loss, and one of those explained that the loss was made up by new members.

Consortial staff reductions, organizational restructuring, service additions, and many service eliminations were noted by multiple respondents. Three consortia also noted recent mergers. As expected, closed consortia did not respond.

Thirty-three unique consortial respondents listed funding and related issues as both a current and a long-term challenge. Our survey included two questions about significant issues faced by library consortia. The first question was: “Please describe the most significant current challenges that your consortium is facing.” Twenty-five consortia listed the following issues as major challenges: funding/revenue generation, budgets, and sustainability.

The second question was: “Please describe any major long-term challenges that you believe will affect your members and/or your consortium.” The survey did not include check boxes about current and future challenges. Since more than half of the respondents answered this question, the authors concluded that they were correct in their hypothesis that the economic downturn was still strongly affecting library consortia. Seven consortia reported declining funding from membership as a challenge. On the other hand, six consortia reported increased funding or activities. Additional issues raised included insufficient staffing (listed by six consortia), physical delivery (listed by three), library staffing, small libraries, and school libraries.

Services

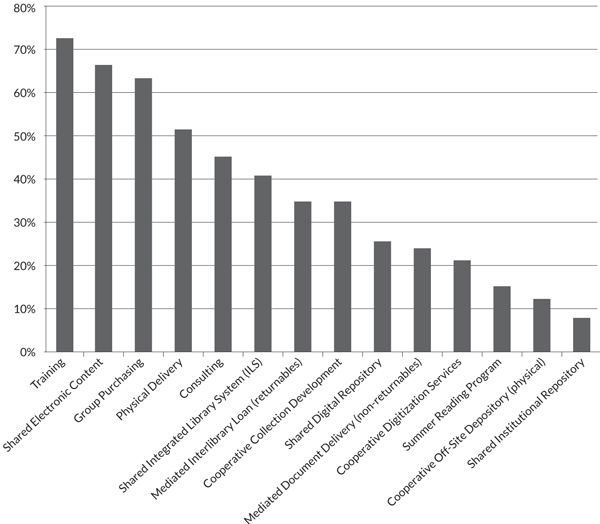

The most widely offered services provided by US library consortia, as listed by more than 50 percent of respondents were:

• training

• shared electronic content

• group purchasing

• physical delivery

The next most common services, offered by 24 to 50 percent of respondents, were:

• consulting

• shared integrated library system (ILS)

• mediated interlibrary loan for returnable items

• cooperative collection development among members

• shared digital repository

• mediated document delivery of nonreturnable items

The chart below illustrates the range of services and the respective percentages offered by US library consortia. Many of these services play a part in the discovery-to-delivery process that is covered in depth in chapters 5 and 6.

Figure 2.1. Services Provided by US Consortia as Percent of Total Respondents

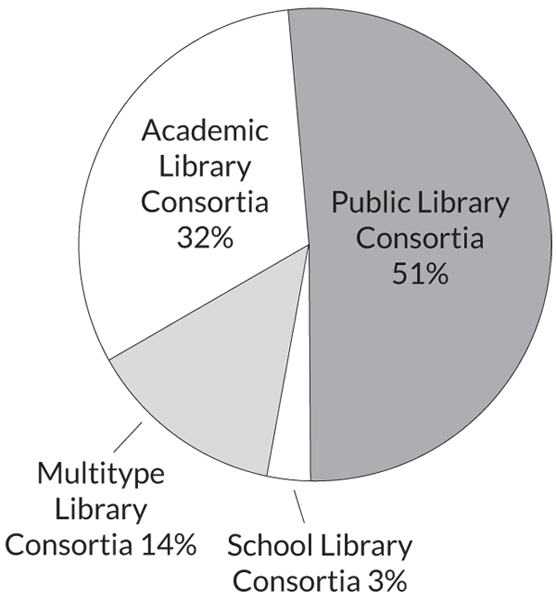

The aggregate library membership of the 66 responding US consortia is 18,142, with an average membership of 236. Median membership is 53 libraries, with 34 percent of respondents citing membership exceeding 100 libraries. Public library consortia comprised more than half, or 34, of responding consortia. Academic consortia were the second largest group of responders, with 21 returning surveys. Six of the academic consortia included either the state library or a handful of other members with academic libraries constituting the vast majority of members. Nine respondents were from multitype consortia, and two were statewide school library consortia.

Figure 2.2. Consortia by Library Type

Figure 2.3. Aggregate Revenue Sources for All Reporting Consortia

Budgets and Revenues

Our 2012 survey included questions about annual budgets and sources of revenue. Of the 60 consortia that reported annual budgets, the highest was $23,700,000 and the lowest was $3,000. The average budget was $2.9 million, with the median budget about $1.2 million.

The survey asked consortia to provide information about their sources of revenue, and 54 respondents gave the following information to illustrate aggregate funding sources:

• membership dues revenue: 39 percent

• state funding: 30 percent

• fees for services: 19 percent

• other sources (often LSTA and other grants or cost sharing): 12 percent

Membership dues income is the most significant revenue source for 17, or 31 percent, of respondents. For 12 consortia, membership dues comprised more than 90 percent of their overall funding.

State funds are the most significant funding source for 11 consortia, or 20 percent, and comprise 30 percent of the aggregate funding. The economic crisis that began in 2007 led to state budget cuts, and 8 of the 11 consortia that rely heavily on state funding indicated that they had to cut staff and services because they lost some state funding.

Mergers and Consortial Collaboration

Consortia in five states merged or closed at least partially as a result of the 2008 economic crisis. As noted above, the simultaneous realignment of the relationships between OCLC and service networks, as well as the economic crisis, led to the closing or merger of nine OCLC service networks. Three OCLC networks expanded due to the mergers.

Consortia in other states are taking the following steps to work together to improve services and efficiencies.

• New York’s nine 3Rs regional library systems recently published a study on the potential for statewide collaboration, including steps planned for working together, in I2NY: Envisioning an Information Infrastructure for New York State, which can be found at www.ny3rs.org/wp-content/uploads/2012/11/Final-report-5_20_2013.pdf.

• Wisconsin’s 17 library systems completed a study of the role of library systems, how to increase their relevance through collaboration and service standards, and the impact of possible mergers, which was reported in Creating Effective Systems, found at www.srlaaw.org/2013Process/CreatingEffectiveSystems8-2-13.pdf.

Interstate physical delivery, which is only possible when consortia work together, has been in place for over a decade in Minnesota, Wisconsin, and the Dakotas and for five years within Colorado, Kansas, and Missouri consortia. Massachusetts also has a joint project, noted in our survey, in which three shared integrated library systems are working together on an Evergreen open-source ILS platform. In Florida multiconsortial collaboration includes a shared discovery platform and the development of webinars for statewide access.

Two collaborative projects of note that allow multiple consortia to leverage their strengths include Califa and its Enki e-book platform for hosting and delivering libraries’ digital content (see Case Study 2, The Enki Experiment) and the wide deals sponsored by LYRAIS and the Center for Research Libraries (CRL). The wide deals allow multiple consortia to benefit from the negotiations for expensive scholarly journals and other electronic content by major players in consortial agreements (see Case Study 5, Embracing Wide Deals).

In Massachusetts the merger of six regional library systems into a single statewide organization was necessary following drastic state budget cuts in 2010. Some benefits of consolidation emerged. The merged organization is better suited for making statewide decisions. This has led to increased buying power for electronic content through a single bid process in collaboration with the state agency. On the other hand, some libraries lost access to local content that was very important to them because they lost local regional system support. One of Massachusetts’ challenges is to develop a statewide model to assist libraries in securing licenses for local content.

An additional example of statewide collaboration in Massachusetts is a planned statewide e-book platform (see Case Study 3, Statewide E-book Project for Multitype Libraries in Massachusetts). This project grew out of a call to action following a statewide program on resource sharing hosted at the joint expense of the state library agency and the statewide consortium. Funding such an event and reacting quickly to the call for action would not have been as straightforward under a system with multiple regional systems that each had separate budgets and decision-making priorities. Massachusetts’ challenge now is to ensure that all libraries are able to benefit from this statewide program and that no one loses sight of the need to support traditional resource sharing as it embarks on this new venture.

Library consortia must focus on the needs of their own local audience. This is a financial imperative because membership dues, state funds, and fees for service sustain these organizations. There are situations, however, when working on a larger scale can benefit members and consortial organizations. Determining the right size is not always based on rational or logical bases. Geography often guides such decision-making. However, when it comes to joining forces with other consortia, logical measures are employable.

Economy of scale or coherence of scale is worthy of consideration when planning consortial services and projects. The Council on Library and Information Resources and Vanderbilt University partnered to form the Committee on Coherence of Scale in 2012. The Committee is considering correlation among several consortial projects, including the Digital Public Library of American (DPLA), for business plans, costs, sustainability, and other aspects related to scale.

I have taken the liberty of extrapolating on membership numbers and financial influence in our survey results in order to speculate on the potential benefits of expanded collaboration among consortia. If the estimated 150 or so consortia that did not respond to our survey were of median size and had a median budget of about $1.2 million, the total aggregate number of libraries involved would exceed 26,000 and the aggregate budget would exceed $349 million. That’s a lot of buying power and influence. Granted there is some overlap in membership because some libraries belong to more than one consortium.

Two large consortia, OCLC and LYRASIS, act in some sense as megaconsortia or consortia of consortia. The DPLA has the potential to join them. Might these organizations play an increasingly valuable role in bringing consortia together for more efficiency and enhanced buying power? OCLC has been supporting consortia for years; first, with its primary service of providing access to MARC records, later with an interlibrary loan system, and more recently with discovery and integrated library system services. Consortia have taken advantage of these opportunities with varying levels of participation.

OCLC is a cooperative of librarians, institutions, and organizations worldwide. In 1967 a small group of library leaders believed that if they worked together, they could find solutions to the most pressing issues facing libraries. These leaders began with the idea of combining computer technology with library cooperation to reduce costs and improve services through shared online cataloging. Today as technology has made the world smaller and the reach of libraries greater, OCLC has grown into a worldwide organization in which 23,000 libraries, archives, and museums in 170 countries participate. And the OCLC cooperative is helping libraries define their place in the digital world with new web-scale services that amplify and extend library cooperation even further.

OCLC works through a global network with nearly 600 consortia and groups to connect libraries to manage and share the world’s knowledge and to form a community dedicated to the values of librarianship, cooperation, resource sharing, and universal access. OCLC’s work with groups varies broadly. It provides group purchasing options for OCLC services such as WorldShare cataloging and interlibrary loan services, virtual reference with QuestionPoint, and resource sharing with VDX. OCLC also provides WebJunction professional development training and training opportunities to member libraries through its Training Partnerships with library consortia.

LYRASIS is a geographically broad consortium. It has the reach, administrative infrastructure, and mission flexibility to work with and across many consortia. LYRASIS acts as the licensing agent for several consortia and works with cooperatives and state library agencies on their licensing agendas and other projects. LYRASIS also works with consortia to coordinate interest and develop interconsortial licenses that benefit multiple organizations with administrative services and group discounts. LYRASIS is active in the open-access community and is working with other organizations to support the movement. For example, LYRASIS is the US agent for SCOAP3 a global project to move high-energy physics journals to an open-access model.

The International Coalition of Library Consortia (ICOLC) has been hosted and supported by LYRASIS for some time. ICOLC facilitates information sharing and networking opportunities at little to no cost to participating consortia. There is no fee for membership or online participation in ICOLC. ICOLC has strong international participation and hosts two annual meetings: one in the United States and one abroad. As an adjunct to ICOLC, LYRAIS also hosts what has become an annual consortial summit meeting. This event includes presentations by participating consortia and conversations about topics of mutual interest.

The Digital Public Library of America (DPLA) launched in April 2013 after a long consensus-building process to create what promises to be America’s premier digital library. DPLA was created with substantial grant funding and with wide participation by the library community. It has also provided grant funding to a number of hub institutions and consortia to facilitate the expansion of access to available digital content. DPLA is examining how to remain sustainable and continue to fulfill its mission.

Conclusion

Larger, more efficient consortia are moving forward with important efforts to empower and assist member libraries. The five-state wave of consortia consolidation after the 2008 recession was preceded by a three-state wave in Colorado, Connecticut, and Ohio in 2003–2005, during which 20 regional library systems merged into six. In the past decade 79 library consortia have ceased operations. The latest wave of consolidation could continue to grow as resources are spread thin in a slow-growing economy and as potential efficiencies are realized.

The competition by consortia for state funds is an ongoing challenge. At the national level, LSTA funding from the Institute for Museum and Library Services has been threatened for several years and additional threats are looming.

Two essential priorities for a consortium are local needs and efficiency. Paths to efficiency might include the interconnection of ILSs and web-based access to e-content and resource-sharing services, which would enhance discovery-to-delivery services. The library of the twenty-first century is likely to play a continuously growing role as a community center, be it on an academic campus or in a municipality. The role of consortia in empowering and capacity-building for libraries is strengthened by the growing ability to communicate, meet, and participate in virtual training and consulting services. The need to be located close to members has become less important. That is not to say that the value of a nearby connection to personnel is diminished. Rather, it has simply become unaffordable when other services have a higher priority and technology facilitates virtual people-to-people connections.

Partnerships, multiconsortial efficiency, and outsourcing have great potential to enable consortia to meet member needs more effectively. On the upside, merging consortia has already brought much greater efficiency of scale in some states. On the downside, budget cuts have led to reduction in some services as priorities are reset.

The major challenges facing consortia fall into the following areas:

• sustainability of operations due to decreased public funding or member dues revenue

• effective communications and marketing with a member base that is short-staffed and overly busy

• successful negotiations with vendors that continue to increase pricing or are unable to offer advantageous discounts because of their own business and financial pressures and/or consolidation in the marketplace

• support of large-scale library resource-sharing as libraries transition from traditional physical library materials to e-content

• licensing popular e-book content that will satisfy members’ patrons

Opportunities include sharing and partnering on services, such as:

• discounts (wider pools to reduce management/administrative efforts)

• generic resources (including access to shared library policies and job descriptions)

• interstate physical delivery (as interstate discovery improves, use of these traditional materials will decline more slowly)

• licenses (wider pools to reduce management/administrative efforts)

• licenses on emerging content and developing partnerships with vendors

• non-copyright content (including open access and MOOCs)

• shared repositories (physical and electronic)

• technology platforms and development (including open-source)

• virtual training and consulting

Professional activities and networking opportunities for consortial staff and managements are available with the following:

• American Library Association’s Association of Specialized and Collaborative Library Agencies (ASCLA)

• International Coalition of Library Consortia (ICOLC)

• LYRASIS

Consortia collaborate on many fronts, and some work in the areas mentioned above is in progress. The Enki e-book platform, described in case studies in this book, is in an early stage of collaboration between several consortia that are attempting to resolve the dilemma of hosting owned e-book content when a commercial host is unsatisfactory or unavailable. Anne Okerson’s case study on the wide deal shows a multiconsortial benefit when consortia band together to seek advantageous pricing. Kathy Drozd, at Minitex, describes a successful interstate delivery system with cost-effective, efficient services in four states. Jay Schafer’s case study on a shared print project includes multiple consortia taking shared responsibility for housing hard copy of vital scholarly content and freeing up valuable space in libraries in several states for other important purposes.

Several areas deserve further exploration. A chart that outlines the e-content and print spending of every consortium would be enlightening. What is the aggregate spending of more than 200 library consortia’s members on library supplies? What if there were only a few online marketplaces for our members to choose from? Aggregating our purchasing power could provide a great deal of clout. One challenge is to maintain competition among vendors.

How will the megaconsortia look in the future? They are already addressing some of our needs. Where could we gain the most from a joint investment? Perhaps the answer is in the vision of Library Renewal with a shared e-book platform and marketplace where librarians strive to develop mutually beneficial relationships with publishers and serve them up for consortia and their members to shop. The technology standards could be developed efficiently, the aggregate use of materials could be measured, and fair pricing models could prevail. Such a project would provide a tremendous benefit to consortia that serve public libraries where ownership of e-books is not assured by existing aggregators.

The next two chapters look at how consortia manage the services offered. Given the financial difficulties found in our study and the key value consortia services offer participating libraries, these chapters help map out a path for sustaining library consortia. While our research suggests times are better for library consortia going into 2015, there is still a great need for library consortia to engage in best practices and excellent customer service.