Khindaswinth was an elderly barbarian who, being a Christian, might have acted differently. Bishop Eugene, in a poem not intended for publication, makes him a monster. Fredegar, further away, gives a telling, if inexact, number of his victims and adds that the Goths would respond only to a firm yoke. To many Goths it seemed that he represented traditional claims to supremacy defended by force. The concession to primogeniture had proved unacceptable. He intended to assert himself in the face of the Roman church and was not the man to forgo the right to appoint his own metropolitan bishop. He was in no hurry to convene a council of Toledo. His gold trientes obey the usual standard of purity, which he could afford to maintain. He issued them from 21 mints, including all the provincial capitals, even Braga and Tuy, and six or seven small places in the north-west. He is usually called pius, but iustus at Tuy and victor only at Mérida, where it is possible that he met with armed resistance.¹¹⁹ His campaigns are unrecorded. Eugene II was a poet, not a historian, and it is here that the acts of the councils are deficient. When Eugene I died, Khindaswinth demanded the appointment of Eugene II, formerly a monk of the royal chapel, and then archpriest or precentor to Braulio of Saragossa (631-651), the pupil of St Isidore. Eugene did not wish to go, and Braulio told Khindaswinth that because of his own age and failing sight Eugene was indispensable to him. The king had his way, and a council of the church was held on October 18 646. Only 30 bishops and eleven others attended. Four of the metropolitans came, headed by Orontius of Mérida and Antony of Seville, both senior to Eugene; neither Braga nor Narbonne was present. The bishops did not guarantee the royal family, though they warned that no one should endanger the people of the Goths, the patria or the king, asking rhetorically who could be unaware of the crimes committed by tyrants and deserters who went over to the enemy, or of the disastrous arrogance that imposed ceaseless efforts on the army of the Goths, or of the madness of both laymen and, amazingly, clerics. In particular, the bishops nearer the royal city were to take turns in lending solace to the king. Hermits must spend a period in a community before being released with the consent of the abbot. The rapacity of bishops in Gallaecia was noted: they were not to exact more than two solidi a year from each basilica, or to make visitations with a company of more than fifty.

Eugene II served as metropolitan for a decade (646-657). His private denunciation of his tyrannical master suggests that little could be done to moderate the autocrat, whose legitimate son Recceswinth was brought up in the bosom of the church. Braulio, with Celsus, dux of Tarraconsenis, and Bishop Eutropius of an unstated see, sent the king a suggestio that he should associate the prince, who was young and active and strong enough to endure the rigours of war. It seems possible that the youth had been entrusted to them, Saragossa having been the place from which Khindaswinth made his thrust for power. In any case, Khindaswinth heeded and from January 20 649 shared the reign with his son. Its dual nature is marked by the issue of coin showing both. Recceswinth was born long before his father seized power. An inscription composed by Eugene shows that he was married to Recceberg, who died after seven years of marriage at the age of 22 and eight months. No legitimate child is recorded by her or any other wife. As Recceswinth lived until 672, he had a long widowhood.

Triens of Leovpgild and Triens of Égica.

The dual reign lasted nearly five years, until Khindaswinth’s death in November 653. The known coins of the dual reign are from only three mints, Toledo, Mérida and Seville, and are few in number.

Recceswinth convened a council, Toledo VIII, on December 16 653. It was attended by four metropolitans, Narbonne being absent, 52 bishops, eleven delegates, twelve abbots and eighteen illustres of the palace. The prelates rejoiced in the happy day, ardently desired, and thanked the king for his long and gracious speech, in which he tempered justice with mercy, citing St Isidore on commuting death penalties to reclusion in a monastery and enforcing the laws of Sisnand on Judaism. The lay signatories are ex viris illustribus, not the whole palatine order. The offices show that they were the ministers, military and civil. They heard the royal speech read by, or for, the ruler, which contained his proposals for legislation. They then left, and the doors were closed for the bishops to proceed with their deliberations, taking ecclesiastical matters first and then civil or lay business. All signed the final act: it is probable that the laymen did not do this, but their names were known to the notaries. When the sessions were over, the text of laws was submitted to the palace for promulgation. While bishops came from far and near, and were expected to attend, unless impeded by old age or ill-health, in which case they must send a delegate, the laymen are predominantly those with offices at court or those who happened to be in Toledo. In the list six are comes et dux. It is headed by Odoagrus or Odoacer, comes cubiculariorum et dux, a chamberlain with military standing. Three more have the title comes scanciarum et dux. There are only two non-Germanic names, one being Evantius, comes scanciarum, but not dux. In Spanish, escanciar remains as ‘to toast’, and the office may refer to a butler or dispenser, who organized the rewards of the palatine class and the economy of the household. The other non-Germanic name is Paul, comes notariorum, the royal secretary. There are two Requira and Reccila called comes patrimoniorum, perhaps a duplication, indicating administration of the royal income. Two are called comes spatariorum, commanders of the guard.¹²⁰

The list is followed by a decree which notes that some kings had piled up their patrimony at the expense of the people at large. Many of the mediocres had been ruined with no advantage to the fisc but to the benefit of the palatine officials. All property justly acquired by Khindaswinth should pass to his son forever: the rest should be used for the good of the people, except what was justly owned by Khindaswinth before he came to the throne. Witnesses to the proper ownership of lands, vineyards and serfs should be appointed by the king.

All this is in relation to the code of the Visigoths, which was being drawn up by the palace jurists and was promulgated by Recceswinth, probably in 654. A further general council, Toledo IX, met in November 655, in the church of St Mary. It concerned itself with the behaviour of judges, who were to set an example by their conduct. It resolved points of procedure and required conversosto attend on feast-days with the bishop. Those present were only sixteen bishops, including Eugene II and Taio, who had succeeded Braulio, six abbots and four illustres of the palace, Paul, Eterius, comes cubiculariorm, Ella, comes et dux, and Recchila, comes patrimoniorum. They were the representatives of the group most concerned and readily available.

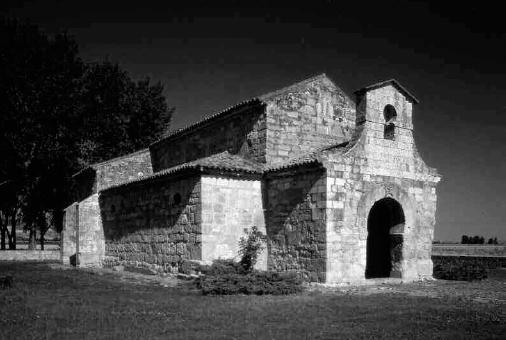

Yet another council, Toledo X, took place on December 1 656. It was to be the last of the reign, and was followed by a silence of twenty years, broken only by the second council of Mérida in 666. The surge of enthusiasm which had greeted Recceswinth at the beginning of his reign was now somewhat diminished. A letter by Taio, metropolitan of Saragossa since 651, shows that Recceswinth was opposed by one Froia, who had roused the wild Vascones of the Pyrenees and had inflicted much bloodshed on Christians. The rebel is not otherwise known, but might be connected with the Froga excommunicated by Bishop Aurasius of Toledo in c. 615. It does not appear that Recceswinth ever commanded his armies. All his coins are marked pius, not victor nor even iustus. In his later years, the command was held by his dux Wamba, who is first noted in 666 and was at his side when he died. Although he was remembered as a loyal son of the church, bonimotus, moved by the best intentions, he was also flagitiosus, which may mean sinful. Both his father and he left illegitimate issue. He certainly founded churches, such as the famous basilica of San Juan de Baños in the Gothic Tierra de Campos, now in Palencia, where a pious inscription was placed in his name in the thirteenth year since his association as king, 699 of the Hispanic era, 661 AD. It stands amid wheat fields in the midst of the group of villages known as the Cerrato. Its internal measurements are twenty metres by eleven, and of the central nave less than six, which may give some idea of the number it could hold.

San Juan de Baños, Palencia, church founded for King Recceswinth.

The Baños of its name refer to the baptistry, important to the Goths. Recceswinth also presented the votive crown from the treasure of Guarrazar, with his name spelt in golden drops and decorated with large semi-precious stones. The wheat fields and the epic tradition preserve the Gothic atmosphere that pervades the area.¹²¹

Within the church, the enforcement of strict conformity raised difficulties for the legacy of St Martin. St Isidore had composed a history of the Sueves without adding to the work of Hydatius, and if he praised St Martin of Dume, his own object was the restoration of the provincial bounds as they had been in late Roman times. He had accepted the transfer of the metropolitan capitals to Saragossa and Toledo within their own provinces, but the church of St Martin still embraced the dioceses between the Tagus and the Douro which had belonged to Mérida and Lusitania. Roman Lusitania had ended at the banks of the Douro, and the northern frontier of the Sueves was on the Minho. The so-called ‘suevic’ coins were not produced in Braga, but in those towns and villages of Gallaecia which had adhered to the church of St Martin in the days of King Miro: they are not marked Suevic, but Moneta Latina.¹²²

St Martin’s church was imbued with the teaching of the Desert Fathers, and his monasticism and her mitages are more adapted to a poorer countryside and less hierarchical than the Roman church envisaged by Isidore. For whatever reason, the metropolitan of Braga did not appear at Toledo in 638 or 646, which denounced the bishops of Braga for rapacity not sanctioned by St Martin and also required hermits to submit to a period of monastic training. Dume itself was an abbey-church like that of the Britones, and formed an enclave in the church of Braga. Until 653, the councils of Toledo appear not to have admitted abbots, but then some appeared in their own right.

In 655 Potamius, metropolitan of Braga, confessed to carnal sin before a panel of bishops and was removed. In 656 Riccimer of Braga, having bequeathed his property to be distributed annually among the poor, the clergy complained that he had impoverished the church: his will was set aside. His successor was Fructuosus (656-665), son of a dux in the Bierzo and a devotee of St Eulalia of Mérida. He compensated the church.¹²³

In the same year Wamba, Recceswinth’s senior general, presented under royal orders the testament of St Martin as well as that of Riccimer for revision. No further step was taken until after Fructuosus’ death when the twelve bishops of Lusitania met under the leadership of their new metropolitan Proficius. The four dioceses, Lamego, Viseu, Conimbriga (moved to Aeminium, Coimbra) and Egitania, now Idanha, were transferred to Lusitania.¹²⁴

These changes following the adoption of the Code of the Visigoths intended to provide a single law for all Recceswinth’s subjects, and later to be his chief claim to be recognized as eminent among Christian rulers. There is little evidence whether his reign was more or less disturbed than others, but the adoption of the single code fell far short of producing the unified state desired by both church and king.

Recceswinth died on September 1 672 at the Villa Gothorum, now Toro on the Douro, the westernmost Gothic settlement before Semura, Zamora, which belonged to the church of St Martin. It was close to the frontier, and he was attended by his army, which at once proclaimed Wamba as king. Recceswinth left no legitimate male heir. His younger half-brother Theodefred was barred from the succession by his irregular birth. It was not until September 18 that Wamba was consecrated in Toledo by the metropolitan Quiricus, who had held office since the death of St Ildefonso in 667. There had been no council of Toledo since 656, and Wamba had not been elected or confirmed by the bishops. It could not be denied that Wamba was the senior dux at, or near, the scene of the last king’s death, as custom demanded. Nor was Wamba a member of the old palace nobility with roots in Gothic Gaul. His name or nickname was a Germanic word for belly, perhaps to be construed as ‘pot-belly’. It was borne by a deacon of Segorbe, Wamba diaconus et Petrus, who attended Toledo VI in 638. The new king came from or acquired the village of Bamba, near Mota del Marqués, Valladolid, on the Leonese edge of Castile.

In Toledo the rise of a powerful plebeian soldier caused some consternation. Quiricus lacked the firm grip held by some of his predecessors. There had been no general council of the church since 656, and when there was, in 675, the relaxation of ecclesiastical discipline was at once noted, and there was a long and detailed profession of faith. It condemned ‘inopportune cries’ and enacted that the metropolitan must instruct his bishops, that abuses by bishops be checked and that there be no diversity within a province and no discord between bishops. The national council must be in the metropolitan city. It was now the fourth year of Wamba’s reign. The council thank ed him f or restoring the church, wished him peace, and made no mention of a guarantee to his wife or family.

Votive crown of Recceswinth.

By that time Wamba had successfully overcome a serious rebellion in the palatine order. The opposition first appeared in Gothic Gaul, once the home of the royal house of Leovigild, where Hilderic, comes of Nîmes, looked for support from his Gaulish or Frankish subjects and neighbours. Paul, vir illustris and comes, a Greek, was sent to negotiate, but on reaching Saragossa, defected with the connivance of its dux Ranosind, whose rank he assumed for himself. Tarraconensis and Septimania joined in the insurrection. Wamba himself marched by way of the Vascones, and Paul declared himself king. He could not expect to rule in Toledo since he lacked the requisite of a Gothic name and parentage, but sent Wamba an arrogant letter calling himself ruler of the east and Wamba of the south. This implied a division of the state which was inadmissible to the Goths and to most of the episcopate. Wamba pursued Paul and captured him in the amphitheatre at Nîmes. He was brought back to Toledo, condemned, tonsured and paraded round the streets seated backward on an ass. His Frankish adherents, probably not numerous, were granted a pardon. The war is the only one of the Gothic kingdom to have a detailed history, composed by the monk Julian, who presented a picture favourable to Wamba.

Once the dust had settled, Wamba authorized the council of November 1 675. It is numbered XI and was attended by only seventeen bishops, eight delegates, and the archdeacon of Toledo and the abbot of St Leocadia. Its purpose was clearly to go far beyond Cartaginensis. Perhaps because of the strong representation of the royal city, Mansi refers to it as provincial. It may have been followed by other provincial councils, but only that of Braga, III, of the same year, is recorded. This was attended by eight bishops: Ourense, Oporto, Tuy, the Britones, Lugo, Iria and Astorga, presided over by Leodigisus cognomen Iulianus of Braga. After the profession of faith, they adopted eight canons. They denounced superstitious practices: only bread, wine and water were admitted in church: the sacred vessels must not be employed for profane use: the bishop must wear his stole: no relics of martyrs were to be hung round the neck: clergy were not to live where there were women except their mothers: no office was to be sold. Thanks were given to Wamba and wishes for a long reign, but without mention of guarantees.

Lay life was regulated by the Visigothic code, which Wamba found already in place and was intended for all his subjects, though Gothic customary and oral practice was not formally abrogated or condemned. Its concepts elaborated by the palace jurists were entirely Roman, yet its most far-reaching consequence was the replacement of Roman legal administration by officials nominated by the crown or its delegates, but leaving the collection of tribute in the hands of numerarii, a duty Goths regarded as beneath their dignity. The code lists the judicial hierarchy which was to apply it. The king was commander of his armies, as well as the head of the judicial system: Recceswinth is remembered as a giver of laws and seems not to have commanded, though he may have been present when Wamba took the field. On their coins, kings were no longer victor: even the warrior-king Wamba was invariably pius. If kings were required to meet the test of having reached the undefined ‘perfect age’, this was because they must be capable of enforcing their decisions on their peers. In Aquitania, where the Gothic third became two-thirds, the Theodorics applied oral and customary law to their optimates, who alone might present the quarrels of their clients. For the Romans, the laws of Rome were administered by a system answerable to the pretorian prefect at Arles, with (for the senatorial class), appeal to the senate of Rome: church property enjoyed immunity. Under the ius of Euric, royal authority had extended to Aquitania I, and the king’s Roman jurists had produced a code to protect the interests of Romans in their quarrels with Goths. The system was altered by the adoption of a single religious confession. The seat of legal studies was Seville. As Hydatius shows, there had been constant friction between Sueves and Romans, who preserved their Roman rector or urban magistrate in Lugo and probably other places, but it fell to the bishop to defend the general interests of his flock. For Isidore in 619 the great object was the application of Roman law in its entirety, with due respect for Gothic strength and military practice. The Visigothic code promulgated by Recceswinth was drawn up by palace jurists, who combined the codes of Euric and Alaric and laws called simply antiquae of whatever date, making the large assumption that the church was sufficiently covered by the right of bishops to participate in the consecration of a pious king, who would know how to deal with the vestiges of Gothic tradition.

Under the king, the hierarchy was set down: first, the duces and comites and their vicarii, who might correspond to the optimates and viri illustres. Then came the thiufads, commanders of a thousand, clearly of military origin. In Roman times a comes had been the companion of the emperor entrusted with the execution of his policy in some particular mission: Procopius notes disapprovingly its abuse in the sixth century for the leader of any band or contingent. The dux, properly any constituted leader, had now become superior to the comes. In broad terms, the dux commanded the troops in a whole province, while a comes was governor of a city. Those of the palatine order, the illustres, included those in charge of various offices. There were also a small number of proceres, perhaps members of previous or current royal families. The laymen, who attended Toledo VIII in 653, numbered eighteen, as compared with over fifty bishops.

The Visigothic code relegated the Roman judge or magistrate, the rector, to the lowest place. The professional judicial hierarchy was replaced by an order which was in origin military since even the comes now executed both functions. The code itself said nothing about one important subject, military service. Wamba filled the gap in November 673, only weeks after the suppression of Paul’s rebellion. His ‘military law’ was prefaced by a reference to the decline in patriotic spirit. It required all those in authority, lay or ecclesiastic, to provide contingents forthwith on hearing of hostile action within a distance of a hundred miles. The penalty for failure to appear was confiscation of property, reduction to servitude or death by royal order: clergy might not be exiled. It is scarcely surprising that the repeal of the law should become a matter of moment with the bishops. They were opposed to the death-penalty and required the king to give an assurance that it should not be applied before allowing clergy to participate in any judicial capacity in which it might be invoked. The gravest penalties for the clergy were reclusion in a monastery or expulsion from the church and disgrace in a public ceremony; lesser faults seem to have been dealt with by an episcopal court in camera.

The military law affords a further glimpse of the Latinized Gothic hierarchy. After the thiufad or millenarius, it adds gardingus and any person holding a position in the place concerned or the vicinity. Gardingus appears for the first time, denoting as a separate class members of the royal guard. It was used as a proper name by the bishop of Tuy, who attended Toledo IV in 589. It now gave access to the palace nobility. A lady of noble extraction Benedicta is described as ex gardingo regis sponsa.¹²⁵ The guards raised by, or for, Wamba were thus brought on to the payroll of the fisc. There are no means of calculating the cost of the palace nobility and the professional military class to the payer of taxes. It was accompanied by the cost of new fortifications to Toledo. Wamba’s buildings are recorded in an inscription preserved in the later Continuatio: unfortunately it does not say where the inscription was placed. Most of the existing walls of the royal city were rebuilt or added in the Middle Ages. The growth of military expenditure required higher taxation and a closer scrutiny of existing sources. Wamba’s gold trientes came from only five mints, corresponding to the provincial capitals, Toledo, Tarragona, Seville, Cordova Patricia and Mérida. None is known from either Narbonne or Braga. There is a slight decline in average fineness, due chiefly to variation between specimens from the same mint. Miles knew only 131 coins of Wamba’s reign of eight years, as compared with 247 of Recceswinth’s reign of nineteen, or 660 of Swinthila’s of ten years. No less significant is the fact that of the 131, 41 are from Toledo and 46 from Mérida, the two greatest military cities, and only seven from Tarraconensis, which shared the fate of Gothic Gaul: Gallaecia is also lost sight of.

The restriction of mints to the provincial and metropolitan capitals is reflected in the reform of the diocesan boundaries. Wamba is credited with a more precise definition of each episcopal area in the Divisio Wambae, which shows the four points where each diocese touched its neighbours or the sea. It is preserved in many manuscripts, none of them earlier than the twelfth century, and has been given an apocryphal prologue. Many of the points named are not now identifiable, being remote and isolated settlements at a distance from the bishop’s see, but those that abut on the sea appear correct. The diverse changes arise from local interpretations or amendments which cloak an authentic original intended to be permanent.¹²⁶ The Divisio varies in its versions. The number of sees under Seville was nine, but one version adds Tangier, harking back to a remote past. Gothic Gaul has six to nine, Toledo seven to twenty, Mérida seven to fourteen, and Braga eight to fourteen. At the councils of Toledo attendance was compulsory, but apologies for absence from the aged or infirm were accepted. The largest number to attend a council was 69 (III, 589), when some sees had two bishops and not all were represented. Among the charges later levelled against Wamba was the accusation that he had created dioceses where formerly there were none. Only one case is presented to substantiate the accusation: Steven, metropolitan of Mérida, had been obliged to consecrate a bishop at Aquas. There are more than one Aquas, but the one intended was Aquas Flavias or Chaves in Portugal, to which Bishop Hydatius had withdrawn when the Sueves occupied Braga. It was not a see before nor later, but was believed to guard the relics of Pimenius, the Desert Father whose apophthegms are most often quoted by St Martin. It is likely that those who advised Wamba considered Chaves an authentic see.¹²⁷

Wamba’s defence programme was set off by the rebellion of Paul, not by any external threat, except in the sense that he was threatened with secession, which might bring Frankish intervention. It did not do so, and Wamba prudently spared the few Franks involved. The language in which the military law is couched and the fortification of Toledo seem to imply that the court apprehended internal disorders more than foreign invasion. Wamba himself appears to have shown no special concern for the question of Judaism or for the church’s desire for conversion. The Greeks in their present weakened condition were in no state to intervene, however much they might regard the Goths with suspicion.

A medieval source, the Chronicle of Alfonso III, composed before 900, says that in the time of Wamba a fleet of 270 Saracen ships attacked the Spanish coast and was defeated: all were burnt or sunk. It is echoed by Lucas of Tuy (1239-49) but otherwise unrecorded. The number of ships can be disregarded, but the chronicle of Alfonso III has information now lost and should not be dismissed too summarily. The Muslims had occupied Alexandria since their sudden conquest of Egypt in 640. The caliphate was established at Damascus in Syria, and their rulers combined boldness with caution. They had the advantage of Greek converts, whom they knew as Romans or Rum. Their land armies were fired with zeal and the promise of a just distribution of booty, but they had strict injunctions not to take risks at sea. The sea-trade of Antioch was in decline, but Alexandria was not only an international community but the leading commercial centre of the Mediterranean. Its name commemorates the Greek conqueror whose travels took him as far as India. Leontius, in his Greek vita of John of Alexandria (early 7th century), notes that its merchants reached the Britains, where they exchanged wheat for Cornish tin. The city also had a famous library and was a centre of learning, preserving the Athenian tradition of contending philosophies. It produced heresies, not least among them that of Arius. Not far away in the waste beyond Thebes, the Desert Fathers had a cluster of monasteries. It submitted to the Muslims, though their military government was at Cairo, ‘the conquering’ or Misr, Egypt. They explored by inland routes the adjacent provinces of Tripolitania and Libya, the true Africa, their Ifriqiyya. Their forces were not large and were not invariably victorious. Their historians, writing much later, are neither annalists nor gatherers of documents, but rely heavily on hadiths, traditions or oral accounts by participants, transmitted by those of acknowledged honesty. The Arabs had an oral tradition of poetry and story-telling, and were not now much interested in their own history before the teaching of Muhammad or in that of the peoples they conquered. Nor did the Byzantines speak of their own losses. West of Alexandria, the only great trading city was the ancient port of Carthage. The city itself remained Greek until the end of the seventh century, whether ruled from Constantinople or not. In Africa proper, the towns and villages and Berber tribesteads were Christian.

The Arab historian ibn al-Athir (1160-1223) places the first conquest of Tripoli in November 642.¹²⁸ An earlier writer, ibn al-Hakam (802-891), says that the Emperor Heraclian appointed one Gregory to govern Africa from Carthage. He rebelled, minted his own coin and ruled the whole area from Tripoli to Tangier before being killed in battle with the Arabs, who took booty and a payment of tribute to stay away.¹²⁹ Ibn Khurradadbah (c. 844) calls Gregory patrician and says that his stronghold was Sbaitla, Suffetula, the city of Byzacena far to the south of Carthage: it fell in 657. It was only in 670 that Qairàwan was founded as a forward camp on the border of Tunisia. Under the Emperor Constantine IV (668-683) the Byzantine eparchy extended through coastal Mauritania to Ceuta, but the authority of the Greeks did not extend much beyond the ports and coastal towns. Many Berber communities, here Moors, enjoyed independence. The Muslim advances were by land, leaving the Greeks in an increasingly tenuous control of the seaboard. In what form and when these events came to the notice of Wamba is unknown. He was less preoccupied than the church or the merchants may have been. He did not press the anti-Jewish legislation, and his defence programme was as much directed towards internal rebellion as against foreign invasion. Bishop Quiricus, who had consecrated him, died in January 680. He was followed not by a Goth nor by a Roman but by the monk who had composed the history of his war, Julian of Toledo, born a Christian, but of converso parents. His reputation for learning was almost as great as that of St Isidore, though it inclined towards theology rather than classical antiquity.