Who then were these Goths who were to sack Rome, put an end to its glory and form their own empire in the western prefecture? According to myth, they were a Germanic people sprung from Scandinavia who had crossed the Baltic and landed with the Gepids on the East German or Polish shore. They pushed their way south and east to the Carpathians and divided; one body, the Visigoths, entered Dacia, while others resorted to the steppes of the Ukraine and the Crimea, where they were known as Greutings or Ostrogoths.

They were certainly Germanic and neither nomads nor navigators, but peasant-farmers, and had absorbed other peoples on whom they imposed their command and language. The Dacio-Getae had some contact with a Romanized population, and their use of wagons implies a knowledge of woodcraft, and that of skins or pelts of hunting and sheep-raising. The archaeology of Romania made important finds between 1950 and 1970, and shows the complexity of races that had inhabited or passed through Transylvania.⁵ In 1830, the treasure of Pietroasa was uncovered in the midst of Gothic territory, and was thought significant enough to be exhibited in London. It comprised an array of vessels, fibulae and ear-rings of gold, often inlaid with coloured glass or stones, of a workmanship comparable to the treasure of Tartessos found at Carambolo near Seville in 1959. It was then attributed to the Visigothic king Athanaric, who died at Constantinople in 381, but later ascribed to the Ostrogoths of the fifth century. A bronze helmet found at Ciumesti is surmounted by a crow with bright red eyes, outspread wings and its head forward. It is no work of farm-hands, but of skilled craftsmen with an artistic feeling in getting the greatest effect from the black bird’s posture. It was made for a potentate to strike awe in the beholder. The Goths were not the first nor the most civilized inhabitants of Transylvania, but were aggressive and as much wedded to their own language and customs as the Romans to theirs.

How much the Goths of Spain knew of their own past remains unknown. Their deeds were retailed by word of mouth in epic poems. Their customs have survived, despite the Latinized laws of their court, in the oral tradition that distinguished Old Castile from the rest of the Spains in the Middle Ages, and their oral epics are reflected in the uneven metre of the Poema de mío Cid, which commemorates the career of Rodrigo Díaz de Bivar, who died in 1099, after carving out a domain for himself in Muslim Valencia.⁶

From early times the Greeks navigated the shore of the Black Sea and founded their cities of Tomi and Hystria near the mouths of the Danube. Herodotus, writing c.480-420 BC describes the uncouth practices of the Scythians and mentions the Getae as the most manly and orderly of the barbarians. Greek architects required the services of native labour, and introduced their crafts and arts, which were imitated by others who were not slaves to classical tradition but used their own eyes. Greek and other merchants traded in luxuries, in clothes and in food, often needed since the barbarians were improvident husbandmen. Among the Romans, Ovid was exiled to Tomi, where he wrote a flood of doleful poems: he claims that he was obliged to learn Sarmatian and Gothic, which may be doubted.⁷ He died, still yearning for the court of Augustus, in 18 AD.

After the formation and abandonment of Roman Dacia, the Goths come into clearer focus. The Scythians disappeared or were absorbed, but their name was bestowed on the Roman province that straddled the lower Danube: in later parlance a Scythian may mean a Roman, a Greek or a Gothic intruder. Constantine I subdued the nearer Goths, building a bridge, probably of wood, over the Danube. He engaged some Goths as federates, in which case their ruler received a subsidy in return for military service, the barbarians forming their own units and keeping their own customs. Those who enlisted in the Roman army renounced their own kings, took pay and arms and followed Roman orders. The Goths did not have coin of their own and were not merchants. The subsidies, whether in gold or in kind, passed back to Greek and other merchants. If payment was withheld, the barbarians might rebel or pass over to the Roman bank. They might also be disciplined by limiting trade to two specified crossing-places. Romans and merchants had the advantage of possessing barges or ships, employed for the movement of troops: most barbarians had only rafts or boats.

Goths continued in Roman service and formed part of Julian’s army in his last campaign of 363. They were sufficiently numerous to participate – on the losing side – in the struggle for the succession which followed.⁸ Some too were settled within the empire, where they took wives and it was supposed that they would ultimately become Romans. At the same period some Goths adopted Christianity in its form devised by Arius, who died in 331. This variant was professed by the Emperor Valens. Ulfila, the ‘bishop of the Goths’, is credited with the translation of the Testaments into the Gothic language which had no previous written form. Ulfila was of mixed race; his father was a man of some standing with adherents. He was consecrated by Eusebius of Nicomedia (328-337), later of Constantinople (337-341). Arianism had been condemned at Nicaea in 325, but was condoned at Sirmium in 357, where Bishop Ulfila was present, and also at Antioch and Alexandria, the greatest commercial cities of the Eastern empire.

Little is known of Ulfila’s missionaries. He himself perhaps never returned to Gothia. It was, or became, usual to employ priests of confidence in negotiations between Romans and barbarians. On April 12 372, Saba and some others won martyrdom by being drowned, on orders from above, in the River Musaeus or Buzãu. A letter describing his passion made him widely known.⁹ But the work of the missionaries had not then gone very far.¹⁰ A single reference makes Queen Gaatha, ‘wife of the king of the other Goths’, the person who collected the relics of the martyrs of 372. Ulfila came of a family of notables and may have approached the wife of a ruler.¹¹

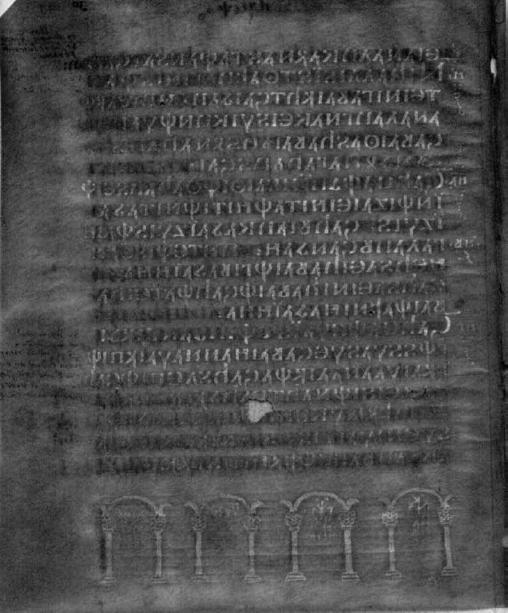

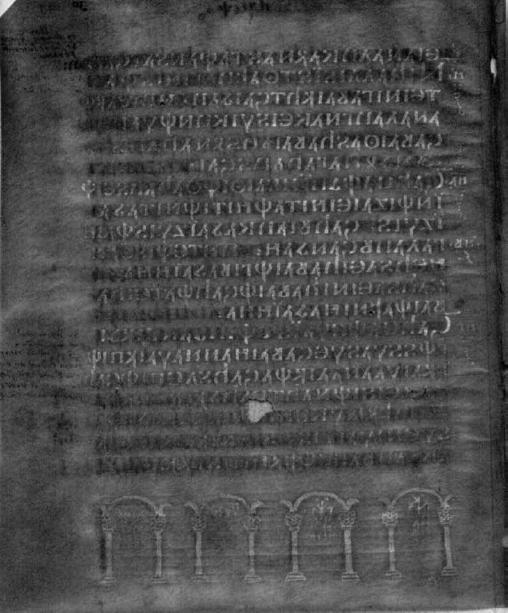

Page from Ulfila’s Gothic Bible, c. 380, copied c. 500.

Although a great Spanish medievalist, Claudio Sánchez Albornoz, thought that the Goths elected kings ‘democratically’, this has more to do with the ill-starred Spanish Republic of 1931 than with history. The Goths were governed by leaders known to the Romans as optimates or magnates, and to themselves as megisthanes, the Gothic oblique case of a corruption of Latin Magister (militum), a general.¹² These leaders met in time of war to choose a commander or king from among their number. There was no question of participation by their inferiors unless by shouting. If the king or commander failed, he was at once replaced and killed. It was no place for a woman or for a youth unable to enforce his decisions. Their religion had probably been of protective idols charged with guarding their villages and crops. The case of Saba implies that their own priests were appointed by the optimates, who perhaps saw Christian priests as a threat to their authority.

From about 370 the challenge to the Ostrogoths came from the Huns, mounted bands who descended on the villages, took what they wanted and burned them before riding off with their loot. This may not have been entirely new, but the Goths, who had absorbed other peasant peoples, could not dominate the bands of nomads. One of their kings, Hermanric, on being worsted, took his own life.¹³ The report soon spread. Many Ostrogoths fled to the Visigoths, communicating their alarm. Ammianus says that there came a rumour that a barbarous multitude of unknown people had driven them from their homes by sudden force and was roving in confusion about the Danube. At first, such reports were ignored since in those parts wars were often not heard of by those dwelling at some distance until they were over. But when the rumours were confirmed by delegates with prayers for the refugees to be received, the news caused more joy than fear: flatterers congratulated the emperor (Valens) on the windfall of recruits that would join his army and make it invincible: officials were sent with transport to ensure that no (future) destroyer of the Roman state or carrier of the fatal plague was left behind. Eunapius says more simply that the Huns overran the Scythians and Goths, who were in danger of being exterminated.¹⁴

The Romans show little of the curiosity about barbarians displayed by Herodotus. The Goths are sometimes called Getae, the form used by Ovid and also Claudian, whose long poem is headed De bello Gothico (403 AD). Procopius, writing in Greek in 550, when the Goths were already in Toledo, uses ‘Gotthike’, with tau and theta. He then appears to confuse the term Gothic with Germanic, saying that there were many Gothic nations but the most important were the Goths, Vandals, Visigoths and Gepids. In ancient times some were called Saramathae and Melanchaeni, ‘black cloaks’ – this may refer to fleeces or pelts. They were distinguishable only in name: all had pale bodies and light hair and were tall and handsome, and had the same religion, all were Arians and had one language called Gothic. They used to dwell on the Ister or Danube until Alaric separated them (Histories, III, ii, 57.)

In view of their long association with the Romans, it is surprising that no particularly Gothic words occur in Roman texts. The single exception is in an anonymous poem called De conviviis barbaris. It says:

Inter eils Gothicum scopia matzia ia drincan

non sudet (audet) quisquam dignos educere versos.

This means: In Gothic, ‘Here, innkeeper (?) meat and drink’ let nobody sweat to make a proper (Latin) verse of this.¹⁵

In the years 372 and 376, the rule of the Pannonian emperors, Valentinian and Valens, was already shaken by the sudden death of Valentinian I at Brigettio, now Szony in Hungary, on November 15 375. His brother Valens to whom he had given the Eastern Part had not proved a successful commander: Valentinian I made his capital at Treveris, Trier, in the Rhineland. Some of his commanders were Franks, who considered themselves truer Romans and resented his brutality. When they adopted Christianity it was not in the Arian form, which struck no roots in the Gauls. The two Pannonian emperors were at best indifferent. Valentinian had legalized his succession by marrying Justina, the widow of Maxentius, who had been considered emperor for three years before being branded a usurper and removed. She bore him his heir Gratian whom, in 367, he made Augustus in the presence of his army at Amiens without reference to the Roman senate. Gratian was then eight, and though educated in the Roman fashion by the poet Ausonius of Bordeaux did not please all the Gaulish commanders. Having calmed the Alamanni with a campaign beyond the Rhine, Valentinian prepared another expedition against the Quads, whose king, Gabinius, had been invited to a feast by the Roman commander and treacherously assassinated. Bands of Quads and others then crossed the frontier and roved in the Pannonias. Valentinian marched in haste from Trier and met their delegates at Szony. On hearing them explain that the raiders were adventurers for whom they should not be held responsible, the emperor burst into a fit of ire so violent that he suffered a fatal stroke in the midst of his harangue. The army at once acclaimed the emperor’s younger son Valentinian II, a boy of four in 375. The reason for this is uncertain. The elder son Gratian was the successor in the West, and the Gaulish commanders may have had no wish to consult Valens, who was far away and had not proved capable: Zosimus says that he could not cope with public affairs and the administration of justice was taken out of his hands.¹⁶ On his first campaign, the Goths took to the hills and there was no conflict, and on the next in 369, he had concluded a truce with King Athanaric.

The Western leaders neither wanted to risk a break with the dynasty nor to perpetuate uncontrolled Pannonians. Gratian was now a promising young leader: perhaps his main defect was that he continued to favour Pannonians and, even worse, the mounted guard of heathen Alans, strangers in the western world. Early in 378 Gratian led a large force from Trier against the Alamanni. His uncle Valens was faced with a major crisis. He had severely punished the Goths in Roman service who had opposed the Pannonian succession. On his first campaign, he had offered a reward for every Gothic head brought in, but had then granted land within the empire to the refugees who clamoured on the Gothic bank to be admitted. They may have included some Huns or Alans, but were mainly Greutings or Ostrogoths bringing their families and possessions. When they began to maraud, the Visigoth Fritigern refused to march against them, at least without payment in advance for the campaign.

The situation was then only a little clearer than it seems now.¹⁷ The Visigoths who had served Rome were inclined to seek imperial protection, and the Ostrogoths, less familiar with Roman ways, were divided, some joining Alans and Huns – with their horses and wagons for carrying families. Others, led by King Athanaric, were disposed to resist, but, as his followers deserted or were depleted, he retired.

Valens was at Antioch, a rich trading-city often called upon to finance campaigns against the Persians, traditional rivals of the Greeks. He returned in haste to Constantinople and marched to Adrianople, an arms-factory and garrison-town, brushing aside Gothic blocks and rejecting a mission from Fritigern to negotiate. He might have received a second approach, but his troops were already engaged. He left his baggage at Adrianople and marched out on the morning of April 9 378, reaching the barbarian camp after mid-day. It was a ring of wagons, or laager. A sudden charge by Alan cavalry took his infantry by surprise. It did not recover, and he was killed, with 35 tribunes and other officers and a large part of his army. Mounted messengers carried the news to Gratian on the upper Danube. The young co-emperor might have urged caution, but he had only light troops, which might not have sufficed, even if his uncle had waited for him.

The victors were ‘all the Goths’, who included sundry others. Triumphant bands scattered over Thrace. They could not reach Constantinople, which was defended by African horse. It was decided to call on the younger Theodosius, lately a respected governor of Moesia and enjoying his otium in Spain, where he had married Aelia Flacilla, the heiress to a land-owning family in Gallaecia, who presented him with his first son, Arcadius, in the same year. He arrived at Sirmium in January 379, and Gratian provided him with two Frankish generals, Arbogastes and Bauto, and gave him on loan half of the border provinces of Pannonia and Illyricum. He arrived at the port of Thessalonica on June 17, and made it his headquarters from which he set about the task of restoring order. It was a formidable undertaking, and to replenish the Eastern army he enlisted large numbers of Visigoths with promises of reward and promotion. This was nothing new but its large scale; hitherto all who dwelled on Roman soil became Romans and had been required to abjure their kingship and customs: if they became Christians, so much the better.

Theodosius was recognized as emperor and made consul for 380. He entered Constantinople on November 28 380, where he resumed negotiations with the Goths. Armed barbarians continued undisciplined and demanded food in the markets without paying: it was necessary to call troops from Egypt to impose order. More barbarians continued to cross the Danube. There were fears that the ‘scythians’ would be overrun and exterminated. They were followed by King Athanaric, who opened negotiations but died outside Constantinople two weeks later. He was given an honourable funeral, and his opportune demise removed for the moment the difficulty of settling a barbarian king on imperial soil. Talks were resumed with Fritigern and others. The agreements were oral and fortified by oaths and pledges: details have not been preserved. If Theodosius was successful, it was at the cost of his tax-payers. Although he was emperor, he was not a member of the imperial family and junior to the youth Gratian, who had problems of a different sort in the Spains, where there was no Arianism, but a rift between Christian catholics, and a division between Christians and pagans.¹⁸

In about 370, Priscillian, a Gallaecian landowner, began to urge the upper class to study the religion it professed, performing ascetic retreats away from sinful cities. His teaching appealed to many in the poorer region of Gallaecia. In the Eastern Part, voluntary poverty, celibacy and monastic communion would not have been questioned: the Desert Fathers had hundreds of hermitages and monasteries, but in the Roman Spains his evangelism alarmed the metropolitan bishop of Lusitania and others, who denounced him for heresy and magic. In October 380, a dozen bishops met at Saragossa, famous for its many martyrs, and condemned him. He appealed to Rome, but Bishop Damasus would not override a metropolitan and a council and denied him a hearing. His friends obtained his election to the see of Avila, that high, cold and frugal town on the meseta, tierra de cantos y santos. He and his admirers in Aquitania appealed to the Emperor Gratian, a sufficiently orthodox young man. But while Gratian was absent on campaign with his guard of Alans, Trier was seized by a usurper, a Spaniard named Magnus Maximus governing the Britains, where he was proclaimed and crossed the Channel to seize Trier. Gratian returned to find the city barred to him. He retired to Lyon, the capital of the large region known as Lugdunensis, where he was assassinated in October 383.

Magnus Maximus had perhaps counted on the favour of Theodosius, his fellow-Spaniard and as orthodox as himself, but Theodosius was far away and busy with other matters, and did not interfere until the murder of Gratian. Thus it was Magnus Maximus who confirmed the death-sentence on Priscillian: he was executed with two clergy and three laymen.¹⁹ The co-emperoror usurper took courage from Theodosius’ detachment to attempt to negotiate with the dowager Empress Justina, who lived with her younger son and daughters at Milan. In 387 as the boy reached adolescence, Magnus Maximus lost patience, was made consul for 388 in Rome and prepared to enter Italy from the north. Justina fled to Thessalonica and besought Theodosius to defend her son. He placed his Frankish general Arbogastes in command and

Magnus Maximus was killed at Aquileia in July-August 388. Theodosius had been left a widower by the death of his Gallaecian wife; their second son named Honorius, was born in September 384. Justina took the opportunity to marry him to her daughter Galla. Zosimus says that Justina arrayed Galla to catch the emperor’s eye, which may well be so, but the match was to Theodosius’ advantage since it brought him into the reigning family and dynasty, whose only male member was the youth Valentinian II.

In the East, Theodosius was in charge, but his barbarian recruits were too numerous to be rewarded equally. His Eastern subjects distrusted Goths the more because of the burden imposed by paying them.²⁰ At Tomi on the Black Sea, the garrison despaired of resisting the swarm of ‘scythians’ until the governor showed by his valour that they could prevail: he was admonished for contravening the emperor’s intentions. The horde was commanded by the Goth Odotheus, not otherwise known. When Promotus, magister for Thrace, received a request or demand from a horde to cross, he arranged a trap so that when they tried to cross by night, the Roman ships were placed together and sank them and slaughtered many illegal immigrants. This was probably in October 386: Promotus was given a training command and put under the orders of Stilicho. The surviving intruders were placed in Thrace and pardoned. They then overran the province.

In his negotiations, Theodosius came to rely on Stilicho, the son of a Vandal and a Roman lady, endowed with persuasive manners, a knowledge of the Germanic tongue and barbarian brashness. In 387 he was entrusted with a mission to the Persian court. The old Sapor II was disinclined to risk further wars. On his death, his heir Sapor III sent an embassy to announce his reign. After an interval Stilicho was despatched to prolong the existing truce which he did by ceding the lion’s share of Armenia, leaving about a fifth to be governed by satraps appointed by the Romans.²¹ It does not now sound like successful diplomacy, but it brought some relief to his overburdened master. At about the same time, Theodosius gave him in marriage Serena, his adopted daughter and child of his Spanish brother Honorius. Their son Eucherius was born in 388.²²

The most famous of the Visigoths Alaric makes his appearance in these years. He did not aspire to be a Gothic king so much as general of the Roman army, recognized as the best of his time, and acted with all the independence that suited his ambition. His presence seems not to be noted before 386, when many of those who came with Odotheus were treated as defeated foes rather than federates. Opposition by the merchants to the burden of taxation was the probable cause of the Revolt of the Statues at Antioch in which the effigies of the emperors were torn down. In 388 Theodosius was again consul, and appointed Rufinus Master of the Offices and senior civilian prefect in the East. He was not on the best of terms with Promotus, the senior of the four or five magistri militum, who aspired to see the young Arcadius married to his daughter. Promotus died in battle in 391, and his command passed to Stilicho. Rufinus, made consul for 392, cherished similar ambitions, but became chief minister to Arcadius, who in the event married Aelia Eudoxia, daughter of the late Frankish general Bauto. The prominence of Gaulish Franks in Eastern affairs arose from Gratian’s sending of Arbogastes and Bauto to Theodosius and to his success in defending Valentinian II: Arbogastes had been left in the West to serve as tutor to the boy emperor and had brought the Gauls into line. On the death of the dowager Justina, Arbogastes arrogated to himself the command of all the Western armies. When Valentinian attempted to show his authority by dismissing him, he ignored the order and sought a more suitable master, Eugenius. In the struggle that followed, Valentinian was killed at Lyon in May 392. Arbogastes and Eugenius sent missions to Theodosius to explain the circumstances and seek recognition: they received no reply.

Theodosius then listened to the appeals of his wife Galla on behalf of her brother. He was now the sole heir to the Pannonian legacy, and when Galla had given birth to his youngest child named Galla Placidia, and died, he prepared to strike back. His elder son was already his successor in the East, and he made his younger son Honorius, Augustus in November 393 at the age of nine, and entrusted him to the care of Stilicho and Serena. Having disposed of the several commands, he left for Italy in the spring of 394. Before leaving, he summoned the Goths to Constantinople for a feast. One faction led by the Scythian Fravitta was in favour of accepting his terms, while others led by Eriulf disagreed. When Fravitta killed Eriulf with his own hand, the imperial guard intervened to prevent the quarrel from spreading. Zosimus’ account is only part of the truth, but Theodosius mobilized his supporters without Fravitta, who was probably thought necessary to hold the remaining Goths together. Stilicho was left in charge of the armies with instructions to bring Honorius to the West once Rome was secure. The usurpers were defeated on the River Frigidus, now Hubl or Wippach, on September 3-4 394, when Arbogastes killed himself and Eugenius was executed. Theodosius did not return to the East, but sent back his victorious Goths.

Alaric was not chosen to lead the contingent that participated in the Italian campaign. Their commander was Gainas under a Roman Timasius, with an Alan named Saul and some Huns from Thrace who served under their chief.²³ In 391 Alaric was in revolt, and was captured and pardoned by Stilicho under some unpreserved agreement which soon failed. Alaric found support from the Goths in Thrace and Macedonia. Some had been settled in Phrygia in Asia Minor and were depressed to the level of miners, peasants and tax-payers, and had some motive for discontent. When Alaric again rebelled, he could not reach Constantinople, but made for Athens and occupied the port of Piraeus by which the city was supplied. The Athenians received him with a small party, feasted him and gave him ‘presents’. Although the barbarians entered unwalled places for food and loot, at other cities they found it more expedient to demand what they wanted and leave them to recover. Alaric attempted to enter the Peloponnese, but withdrew to occupy places in Epirus on the Adriatic, where he was distant from Arcadius and Rufinus, but might either prevent a landing from Italy or pass there if the time were right. His purpose was to obtain pay for his men and recognition for himself. These he had once obtained from Stilicho with Theodosius’ consent: he had little to expect from Rufinus and Arcadius, who had Gainas on hand.

Theodosius died in January 395. His best-known action after his return to the West is his edict that Christianity should be the sole lawful religion of all his subjects. It was issued at the behest of Bishop Ambrose of Milan (340-397), himself a former prefect and civil administrator. Gratian had gone so far as to renounce the title of Pontifex Maximus, but his attempt to abolish the veneration of Victory by the senate soon failed. Many old families were imbued with classical mythology as the central part of their education and regarded Christianity as a religion for the poor and ignorant. Zosimus, himself not a Christian, says that Theodosius addressed the senators, exhorting them to abandon the old gods, using the argument that the state could no longer afford the traditional rituals because of the needs of the army.²⁴

Theodosius’ victory was evoked by the poet Claudian, an Egyptian master of Latin prosody and of classical mythology who recited his first long eulogy for the consuls of 394 and disappears suddenly in 404. His panegyrics are sickeningly fulsome, but so contemporary as to form useful documents. They were composed to be recited before a pagan-educated court. In the first poem, Theodosius appears as a retired Mars reclining under a tree and crowned with flowers. Stilicho is not named. When the emperor died, Claudian became the publicity manager for Serena and Stilicho. He hints at a secret interview in which Theodosius confided both Parts to Stilicho, though Ambrose says that no change was made in his dispositions. There is nothing to show that Rufinus was displaced, or that Arcadius’ seniority was either disputed or acknowledged. The Roman senate certainly regarded itself as senior to that of Byzantium, which rarely claimed parity with it.

The date of Alaric’s second revolt appears to be 395, after the return of Gainas and the death of Theodosius. It suited Rufinus to have him at a distance, though he was not prepared to trust Gainas, whose ample reward was payable in the East for successes won in the West. He arranged the marriage of Arcadius to Eudoxia in April 395, she then being an orphan. It was clear that Rufinus did not intend to submit to Stilicho’s claim to oversee both Parts. In November 395, Rufinus was assassinated by Gainas, not without the complicity of Stilicho. However, Arcadius then appointed his chamberlain Eusebius to be his chief minister. In his two long ‘books’ against Rufinus, Claudian begins by asserting that Ru?nus’ end disproves the idea that wickedness can prevail and shows that a golden age is about to open under two emperors with a single force at their disposal. The soul of great-hearted Stilicho alone took arms against the monster of corruption. Rufinus had stirred up the Getae and the hideous Huns: he started wars which Stilicho won. Stilicho claims both hemispheres and would brook no equal, etc, etc. But if Stilicho hoped that the death of Rufinus would settle things, he soon found that Eusebius was no improvement, and had the advantage of being appointed by the emperor Arcadius, who was now married. Stilicho could not intervene against the East without the support of Arcadius, since war between the two brothers was unthinkable to the senators. Olympiodorus says that Stilicho recommended that Alaric be made a Roman general to occupy Illyricum, still divided, with Jovinus as pretorian prefect there. He adds that Alaric quitted Dalmatia and Pannonia and led his men to Epirus, where he waited a long time and returned to Italy having achieved nothing.²⁵ The fragments of Olympiodorus do not always concur with the later testimony of Zosimus: both wrote in the East. Despite his absurd rhetoric, Claudian is unlikely to have distorted facts for recital before Honorius and Stilicho and an increasingly sceptical court. In denouncing Rufinus he makes the minister admit in terror to Arcadius that Stilicho governed both Parts. In the first book against Eutropius he leans heavily on the fac t that the chamberlain was a eunuch and indulges in more or less obscene innuendoes on the monster’s sexlessness, urging his patron to struggle with the horrible creature.²⁶

The second book against Eutropius declares that Mars summoned Stilicho to war, in which the hero was brilliant and victorious, but he was also forbearing. A diversion was caused in Africa. If Stilicho could not now openly defy Arcadius, there was still the fact that the East occupied Pannonia and part of Illyricum lent to the East by Gratian, and that Africa, on which Rome depended for food, belonged to the East.²⁷ The comes of Africa was Gildo, and Stilicho set himself the task of removing him without disturbing the senate by recourse to war. He undermined Gildo by inciting his brother to rebel. This succeeded in July 398, when the brother was invited to Rome and quietly disappeared. Eutropius could not count on Alaric and did not come out in support of Gildo. The result satisfied the senate, and Claudian left his poem De Bello Gildonico unfinished.

Claudian sang the third and fourth consulships of Honorius in 396 and 398, and also the marriage of Honorius to Maria, the elder daughter of Stilicho and Serena, at Milan in February 398. The attempts to endow Stilicho with a military career are related to the fact that he came of an obscure Vandal father and needed to be justified to senatorial snobbery. The success over Gildo enabled him to seal his relationship with the imperial family and was certainly approved by Serena, mother-in-law of her son by adoption: her own son Eucherius thus entered the line of succession. In his Epithalamium for the wedding, Claudian makes the boy-bridegroom of fourteen the impassioned wooer and prays that her little sister, Thermantia, may make as good a match (she did when Maria died) and the boy Eucherius surpass even his father Stilicho. Eucherius was then ten but by 400 Claudian implies that, riding with the down of early manhood on his cheek, he will marry Galla Placidia: Thermantia smiles as he lifts the veil from the modest maiden’s face. The poems on Honorius’consulates are little more than notes for Stilicho’s heroic biography, making Hebrus run with streams of Gothic blood while Honorius is the young lion learning from him.

In 399 Arcadius made his chamberlain consul and Stilicho refused to recognize the apotheosis of the monster. He now relied on Gainas, who was so well rewarded that Tribigild rebelled, backed by the poor Goths settled in Phrygia. Gainas was made magister to put down the rebels and demanded the sole command, with the cession of notables as hostages to secure himself. They were at last granted, but only after Eutropius had been killed in the autumn of 399, in time for Honorius to make Stilicho consul for 400. Arcadius then awarded the Eastern consulship to Fravitta, who had been a barbarian but was now thoroughly Romanized with a Greek wife. The demand of Gainas for hostages was met but they were killed in July. Fravitta did not escape accusations of treachery for allowing Gainas to escape alive. I t was finally a Hun who killed Gainas and brought his head to Arcadius, who in April 401 appointed Cesarius as his minister and awarded the military command to Fravitta. Here Olympiodorus breaks off and Zosimus is silent, leaving Alaric awaiting orders from Stilicho.

Claudian wrote three panegyrics on Stilicho’s consulate in 400. He then composed his Gothic War and his last panegyric on Honorius’ sixth consulate in 404, Arcadius and Cesarius followed a policy of collaboration with the West until Cesarius was removed in 402 or 403, when Fravitta was executed, a victim of the rising tide of opposition to all barbarians in the East and the demand for their exclusion from the imperial family and the high command. In these years Alaric could not look to the East for recognition: he had once been pardoned by Stilicho, from whom alone he might expect to be paid. From Emona, later Laibach and now Ljubljana, in the disputed part of Illyricum, he might receive recruits from the north or from the east. In 401 he was still unrewarded and entered Italy by way of Aquileia. He did battle with the Romans at Pollentia and Verona. Claudian probably composed his penultimate poem on the Gothic war in 403. It ends with Stilicho’s victory at Pollentia in July 402 (?) and does not mention the second clash at Verona. However, he refers to Alaric’s invasion through Raetia, the Italian Alps, and Stilicho’s journey in the depths of winter by a lake (Garda?) and the snow-clad Alps. Amidst unimaginable privations, he heartened the fields of Vindelicia and Noricum and called in the legions from Britain and Italy and many Germans. Alaric, concealing his fear, addresses the long-haired, skin-clad elders, who warn him not to press his luck. He replies that the Goths have overrun many lands, now hold Illyricum and have only Rome left to take. He reaches Pollentia, not far from Aquileia, where Stilicho harangues his forces. He gives battle. When the Alan leader dies a glorious death in a wild charge, Stilicho throws in the Roman legions and faces Alaric with total ruin. The glory of Pollentia shall live forever. The graveyard of the Goths, it would teach presumptuous peoples never to scorn Rome. There is no description of any victory in the frozen north after the hazardous winter journey. Alaric was able to use the route opened by the Roman usurpers Magnus Maximus and Arbogastes, and the engagement took place on Italian soil.

The last panegyric, for the sixth consulate of Honorius, was recited in Rome in the presence of the plump young emperor, who did not leave the shelter of the marshes of Ravenna between December 402 and February 404. After a suitable invocation on the restoration of Rome’s grandeur, Claudian mentions that he had already sung Stilicho’s war against the Goths. Alaric’s hopes had been dashed and destroyed by the bloody victory of Pollentia, but his life had been spared for political reasons.²⁸ Though humbled, he had come back and was defeated at Verona between the Raetian Alps and the River Po, which added not a little to the Roman success.²⁹

Stilicho was incapable of pursuing Alaric and as in the past bought him off with promises he could not keep. The need for this explains the exaggerated account of Stilicho’s military ability and of Rome’s wonder at his superhuman efforts on her behalf. The bubble was soon to burst, for in 404 it was learnt that another Gothic leader, the Ostrogothic king Radagaesus, was assembling a vast horde of various races for an invasion of Italy. It took place in the spring of 405, when Stilicho gathered some thirty units from all quarters. Lacking the Roman discipline of Alaric, Radagaesus was unable to prevent his men from reaching the cities of the north and breaking up in quest of food and loot. His own band was defeated at Fiesole near Florence, where he was captured and executed in August 405. Alaric had remained at Emona or at Viranum, now Klagenfurt in Austria. He abided by the agreement made with Stilicho, but was well situated both to obtain new recruits and to enrol those of Radagaesus, some of whom were enlisted by Stilicho’s generals: the Goths were ready to command and to be followed by any who would take orders from them.³⁰ If Stilicho had awarded Alaric the title of magister, he was unable to pay him.

Any hope of reuniting the two Parts was abandoned, at least while Arcadius lived. His position had been strengthened since April 10 401, when Eudoxia presented him with an heir, the future Theodosius II.³¹ He was placed under the tutorship of Anthemius, a respected orthodox Christian who opposed the entry of barbar ians into the Eastern establishment without embarking on hazardous attempts to overtake the past.

Stilicho, if he heartened Vindelicia, the territory of the Vandals, had singularly little impact on his father’s people, peasants, left with the West when Gratian divided the Pannonias. They had kings of their own and were infantry, but were at least familiar with the mounted Alans, who served the Pannonian emperors. Their neighbours were now the Quads, a branch of the Sueves which had migrated under their own king towards western Pannonia, now Hungary, where they had brought the reign of Valentinian I to an apoplectic end. From this point, the Vandals begin their thrust westward, precipitated by the strain of the meagre resources of the region and lack of cultivation resulting from the invasion of Radagaesus.

The poet Claudian ceases to be heard.³² His classical mythology faded as the Eastern court sought a reconciliation on more Christian terms, and his rhetoric, however brilliant, was mere posturing. Serena herself, perhaps as much as anyone, was inclined towards her imperial family and its future.

The fact that Stilicho had withdrawn the Roman legions from the western Rhineland was no secret. In the poem on the Gothic war, Claudian says that the legions facing the fair-haired Sygambri and those who tamed the Chatti and wild Cherusci had left the Rhine safe, defended only by the terror of Rome’s name: would posterity believe such a thing? Germania, once the home of peoples so fierce that previous emperors could hardly hold them down, now so placidly responded to Stilicho’s rein that she neither attempted to invade places exposed by the withdrawal of the garrisons nor crossed the stream, fearing to approach the unguarded bank.³³ The legions had gone, leaving the Franks to defend the territory unaided. With the approach of winter the Vandals moved westward, guided by Alans who knew the way through the territories of the Alamanni to the middle Rhine, where corn from the Britains was stored in fortified granaries near the frontier. There was heavy fighting and both Vandals and Alans lost leaders, some Alans deserting, before they crossed into the Gauls taking some Sueves with them. This is placed conventionally on the last day of 406, the River Rhine being frozen. They could not all have crossed in a day. There were bridges at Mainz and Cologne as well as barges and ships. They entered and sacked Trier and other places in Belgica, reaching Taraonna, Thérouanne, near St Omer, barely forty miles from Boulogne. The news alarmed the Britains, where the cities were informed that they must look to their own defence. The capital city was London, once the seat of the elder Theodosius, and the corn from the well-tilled fields on the east side was exported to the mouth of the Rhine, held by well-disposed Salian Franks. There were usurpers, Marcus and Gratian, the second a civilian. They soon failed, but after four months the ‘Celtic legions’ produced a leader named Constantine (III) Orosius says that he was ex infima militia, which Seeck renders ‘ein gemeine Soldat’, and Bury ‘a private’. He was no Napoleon risen from the ranks, but a mature officer with a son named Constans who had been a monk and a younger son, Julian. He had no difficulty in mustering an army, probably of at least four legions including some Franks serving in the Britains, or in organizing the crossing to Boulogne and in seizing Trier early in 407, when the two Vandal kings and the surviving Alans made for the south-west, having learned of the riches of Aquitania, even if they had not read the poems of Ausonius.

Constantine III probably had no cavalry, and, having staunched the open wound of Trier, proceeded down the Rhone to Arles, to which Honorius’ civil and military authorities had fled. There he was welcomed by Apollinaris, the leading Gallo-Roman landowner and senator, whom he made his pretorian prefect. Arles was destined to play some part in the history of the Goths. In Roman eyes Provence, the first extension beyond Italy, was scarcely part of the Gauls. The Rhone was the main artery for the transport of men and goods to the great province of Lugdunum, Caesar’s Celtic Gaul, which took up all central France, and was divided into four Lugdunenses. Arles, favoured by Constantine I, was an important city at the gateway to the more Romanized Gallia togata, where Roman dress prevailed. To its west was Aquitania, divided into Aquitania I, with its capital at Bourges, and II, with its capital at Toulouse and its main trading centre and university at Bordeaux, near the mouth of the Garonne. The north was Belgica, or Germania, long-haired or crinita, also sub-divided. The Alans with their horses, moved faster and further than the Vandals, though their wagons carrying their dependants lagged behind.

Constantine III recalled the first Christian emperor with his British mother: his sons’ names were also chosen to reflect the association with the imperial house. The rapid success of the British Christian divided opinion in Ravenna: the officials and generals from Trier and Arles fled to Ticinum, Pavia, on the Po, in something of a panic. He was assuredly a usurper, but no one else could now control the vast western prefecture. Since the Spains were administered by a vicarius of the Gaulish pretorian prefect, Constantine and Apollinaris found no difficulty in obtaining recognition, at least in Tarraconensis: the Theodosian family, Honorius’ cousins, were great landowners in Gallaecia and Lusitania.³⁴

The only opposition came from a band of Goths led by Sarus, an enemy of Alaric, who crossed the Alps and killed by treachery Constantine’s commanders at Vienne. They were at once replaced by Gerontius, a Briton, and Edobich, a Frank, who obliged Sarus and his band of 300 men to return across the Alps, losing his baggage on the way to bagaudae, rebellious peasants. The defeat was not vital, but made Stilicho’s position in the face of Alaric even weaker, since he was cut off from obtaining recruits from either the north or the east.

The emperor Honorius, on whom the fortunes of Serena and Stilicho depended, was left a widower on the death of their daughter, Maria, and in 408 was married to her sister Thermantia, a child. No heir could be born for some years, so that the prospects of their son Eucherius improved, giving cause for gossip that they intended to make him emperor.

However, the prospect altered on May 1 408, when Arcadius died and was succeeded by Theodosius II, aged seven, and placed in the charge of Eudoxia and the patrician Anthemius. Serena and Stilicho thought of intervening, but could do so only with the presence of Honorius. Anthemius sent Olympius, a Scythian Greek, to represent him at the court of Ravenna. For this purpose, it was thought expedient to have Honorius harangue the troops quartered at Pavia. The discredited officials from Gaul were there, together with the defeated Sarus. Stilicho remained at Bologna. Suddenly there was a revolt among the troops, who ran amok and killed the leading fugitives from the Gauls and many others. It was at first rumoured that Honorius was a captive, and Stilicho prepared to rescue him, but when it was learned that the emperor was alive and in the hands of generals who had shammed sickness in hospital, Stilicho sought refuge in a church in Ravenna. He was extracted under promise of his life and promptly executed by Heraclian on August 23-24 408. Heraclian was rewarded by being made comes of Africa, and Honorius’s chamberlains set out to seek Eucherius, who had escaped to Rome: Serena was strangled under suspicion that she would favour Alaric.

Although Olympius emerged from Ravenna with the guard of Huns, he was unable to cut the Gothic line of communication between Alaric and the Ostrogothic king Ataulf. He reported a victory which was soon seen to be Claudianesque. As winter approached, Honorius was declared consul for the eighth time and Theodosius II for the third, for 409. Zosimus gives this as the time when Constantine III sent a mission of priests or eunuchs to Ravenna to ask for recognition as co-emperor. This was granted. A unique inscription in Greek from Trier commemorates the daughter of a comes Addau who died during the dual hypatia of Honorius and Constantine in July 409. Nothing more is known of her father, a Greek. Trier had only lately been sacked by the western barbarians, but the church in its aristocratic suburb was available, at least for funerals.

Alaric had pushed his way to Rome and camped outside the city. His demands were for recognition, arrears of pay and victuals. The number and dates of his missions to Ravenna and of those of the beleaguered city are not clear. He was able to obtain recruits from Ataulf in the north, and his numbers were swollen by deserters and runaway slaves, whom he readily received. If they were recaptured, their lives were forfeit. They also required supplies. Alaric responded by occupying the port and so threatening Rome’s food, a device he had employed at Athens. His camp outside Rome was occupied in September or October, when the onset of winter most threatened the city’s reserves.

At Ravenna, Olympius was Master of the Offices and busied himself by dismissing those appointed by Stilicho. Jovius, the former prefect of Illyricum, was made chief minister in the belief that he would best know how to handle Alaric. He was given the title of patrician, to match the rank of Anthemius in the East. Olympius’ sally with the Huns destroyed his chances as a military commander, and he withdrew or fled to Illyricum.

There seemed ample reason to recognize Constantine III as co-emperor. It gave him the right to recruit troops, to collect taxes and to issue coin, which he did at Trier and Lyon, the latter with his claim to be restitutor of the empire. It became a centre for his army, doubtless to the relief of Apollinaris and the people of Arles, where he had the seat of his government. To the Spains he sent his son Constans as his Caesar to appoint officials in Tarraconensis, facilitated by Apollinaris and the close r elations between the landowners of southern Gaul and those beyond the Pyrenees.³⁵ Beyond the newer province and the untamed Vascones, Constans found that the family of Theodosius had mobilized their guards and peasants and formed a private army to resist him. Constantine sent his general Gerontius with British or Frankish troops to oppose them. He had already disposed men to block the Alpine passes after the attempted invasion by Sarus. It appears that the British had little difficulty in coping with the improvised army and arrested and killed two of the Theodosians with their wives. Two others escaped to Italy and Constantinople to tell their story. It is not clear when the western barbarians crossed the Pyrenees into the Spains, apparently taking the westernmost route through the land of the Vascones. They are said to have spent two years on the rampage in the Gauls, having overrun Aquitania II, this would give a date in 409. The Aquitanians and Apollinaris were certainly glad to be rid of them. Constantine was still at the height of his power in Arles when he despatched a second mission to Ravenna. His representative was now his north Gaulish minister Jovinus, who optimistically offered to bring all the resources of the western prefecture, the Britains, Gauls and Spains, over to Honorius. Jovinus returned to make good his offer. He had befriended Allobich, the commander. If the Theodosians had already been executed, Jovinus took care to know nothing about it. Constantine himself then prepared a mission which he himself would lead.³⁶ He was clearly not prepared for a campaign, but relied on the understanding reached with Allobich, whose plans were opposed by the chamberlain Eusebius. They fell out and Allobich killed Eusebius. In revenge, Allobich himself was assassinated while leading a procession in front of the emperor, who according to Sozomen dismounted and gave thanks for his delivery from a traitor. The news reached Constantine III as he and his party reached Liburnum in Liguria, before crossing the Po. He at once turned back to Arles.³⁷

The retreat was close to a defeat. In September 409, the appointment of Claudius Posthumus Dardanus as pretorian prefect for the Gauls was made at Ravenna. Dardanus had a long career as governor of Vienne and quaestor and was both a ruthless enemy of usurpers and a zealous Christian. He founded his Theopolis or city of God at Sisteron in the French Alps, and corresponded with St Augustine, who addressed him as beloved and with Jerome on a point of theology, who was equally cordial. This had the effect of destroying the government of Constantine III. Apollinaris was prepared to accept the co-emperorship with Honorius, but not to oppose a ruling of the legitimate emperor. Jovinus, the northern Gaulish minister, was for resisting. Possibly Apollinaris was disappointed with the military performance of Constantine when he resigned. The general Gerontius seems to have agreed. He had been sent to the Spains to support the former monk Constans, now declared Augustus, a promotion Honorius would not have accepted. He returned to Gaul to Vienne, once governed by Dardanus, where he had a house. There he proclaimed his domesticus, probably his son Maximus, as emperor in defiance of Constantine. He attempted to take Arles but failed.³⁸

With Alaric camped outside the city, the state of Rome was almost as chaotic. For a time in 409 the patrician Jovius had been disposed to remove Honorius, though not to disqualify him by maiming, for which the cutting off of a hand or even a finger would suffice. Alaric retorted by proclaiming Attalus Priscus, prefect of Rome’s food supplies and one of the negotiators who at once made him magister and Ataulf, now his brother-in-law, domesticus and commander of his guard. Alaric’s claim for arrears of pay amounted to four or five thousand pounds weight of gold, with hostages as a guarantee, young notables including Jovius’ son. Honorius was willing to permit senators to tax themselves for the payment, but not to permit distinguished Romans to become hostages to buy off barbarians. The negotiations took place at Ariminum, Rimini, some way to the south of Ravenna, and the Romans included Innocent I, bishop of Rome. Jovius waited in Alaric’s tent while Honorius was consulted and messengers came back with the reply. At length, Alaric offered to depose Attalus by removing his insignia and returning them to Honorius. When this was rejected, Jovius protected himself from charges of treason by having Honorius and his ministers take solemn oaths never to deal with Alaric or his kin. Faced with this refusal, Alaric ordered his men to sack the city, the only reward he could offer. It took place in August 410.³⁹

For a short time, late in 409, Honorius’ plight seemed desperate, and he was reported about to flee to the East. But the port of Ravenna remained open. Alaric was himself blockaded. The Goths had no navy and no skill in navigation. At the height of his shadow of power, Attalus had addressed the senators in Rome in a speech full of bravado, promising to restore Rome’s greatness and to recover Africa for her. It was what the senators wanted to hear, and he was held in respect there if nowhere else. Alaric offered to send five hundred men under a Gothic leader to take Africa for him, but Attalus knew that a violent attack by barbarians would be fatal to himself: a Roman province must not be recovered by Goths. Attalus insisted in sending a weak force under a Roman, hoping to persuade or bribe Heraclian, the executioner of Stilicho. There was a long and anxious interval, during which Alaric attempted to reduce other Roman cities, without any success: no other place of any consequence fell to him. Late in 409 Honorius’ fortunes improved, when the East not only sent ships to strengthen the blockade of the ports, but reinforced the guard of Huns and provided gold. Heraclian was stiffened, and if Attalus expected to bribe him he was outbidden. The news came that Attalus’ expedition had failed. The sack of Rome was Alaric’s last card. It satisfied his men for the moment, but left him without resources. He headed towards the south, hoping to capture a port and reach one of the islands. He died shortly after and was buried in the river at Cosenza. His grand design had failed. He was still unpaid, unrecognized and without land of his own. He had destroyed the ancient glory of the city, kept his army intact and still had some Roman adherents, including Attalus and his son, whose return would have been fatal to them.

Alaric’s successor was his brother-in-law Ataulf. In Ravenna, it was seen that the Goths could not succeed, even if they could not be vanquished until an effective Roman commander was found. Ravenna itself was secured, and was shielded by Alaric’s enemy Sarus, who governed Picenum on the Adriatic with his small but seasoned band. The Roman whom Dardanus desired to find was Constantius, a soldier of no special distinction, but of strong ambitions and much shr ewdness. He was sent to deal with the remaining usurpers and given part of the reinforced Hunnic guard. He marched on Arles, where Constantine’s government dissolved, being followed by Jovinus and the north Gaulish troops, who were ready to proclaim him. Constantine had little alternative but to enter the church and seek sanctuary as a priest, opening the gates of Arles to Constantius. It was not a very glorious victory, but it must have seemed so to Honorius and it opened the course of honours to Constantius. Constantine III and his younger son were sent in chains to Ravenna, but were butchered on entering Italy, lest they appeal to Honorius, who had once recognized him as co-emperor and had escaped a similar fate by a hair’s breadth. The heads were exhibited at Ravenna in September 411.⁴⁰

Dardanus would have liked to finish the usurpers by dealing with Jovinus who had proclaimed himself with his brother Sebastian as his domesticus, but a new and more urgent crisis arose. Heraclian, who had been made comes of Africa and thought himself, with the backing of the East, more entitled to glory than the upstart Constantius, assembled a large fleet with his son-in-law Sabinus, and invaded Italy, where he was soon defeated. Sabinus fled to the East and Heraclian was assassinated at Carthage. Constantius, who had organized the resistance, was awarded all his possessions and made consul for 414.⁴¹

Ataulf and the Gothic army had had to find a new policy in 410. It was to turn again to Ravenna. He had one valuable card which Alaric, who had attempted to depose Honorius, could not play. He had captured Theodosius I’s youngest child Galla Placidia, who was brought up at Rome. She was now a young woman of about twenty, with a retinue of her own, which with those of Attalus, formed a party, not at the moment large, but since Eucherius with whom Claudian had matched her was dead, and Honorius had no issue, might well in time prove valuable. The Gothic bishop and historian Jordanes, writing in c. 550, says that Ataulf married Galla Placidia at Forum Livii, now Forli on the Emilian Way, which crosses Italy. No other writer says this, and Jordanes’work is a compound of recorded history and Gothic legend. Even if it were so, Honorius and his Christian chamberlains would not have accepted a wedding by the Arian rite. Nevertheless, the place is where Ataulf probably was.

There is no doubt that the glory of Rome had been smirched and that much of the population suffered dreadful privations. The news seemed so portentous that it amazed later generations and continues to amaze historians. The lack of bread affected all classes, especially those who could not afford cake. The belief that the population was reduced to cannibalism became a commonplace, picked up by Hydatius, who, unlike Orosius and Salvian, thought the barbarians in Spain had also reduced the Hispano-Romans to a similar state. It may arise from the anecdote that at the circus someone cried ‘Why don’t they apply the price control to human flesh?’, or the equivalent, a sample of Roman sardonic wit: it seems not to have stopped the horses, which were also edible, from running. It is a fair speculation that the Goths were induced to leave Italy for Gaul by a promise, to be broken later.