MOST MEN FISH THEIR WHOLE LIVES WITHOUT KNOWING THAT IT IS NOT FISH THEY ARE AFTER.

—Henry David Thoreau

Tenkara means “from the heavens” in Japanese, and perhaps refers to the gentle, almost breeze-soft presentation of the fly. Dry-fly fishing is thus an ideal technique to showcase tenkara’s strengths and introduce the beginner to fly fishing in general.

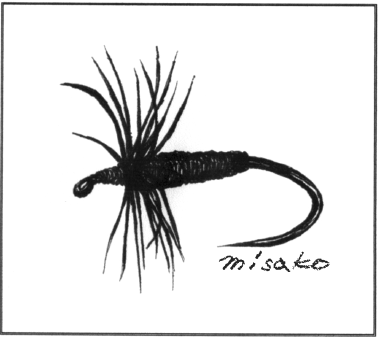

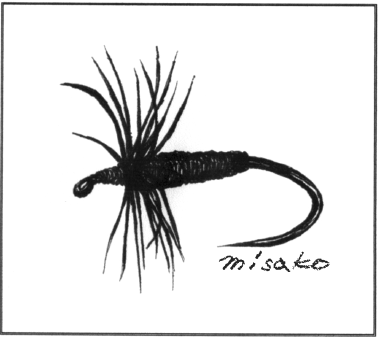

Dry flies, of course, are the delicate flies that are made to resemble insects floating on the surface of water. They are usually made with small bristly feathers wound tightly around a hook shaft. The feathers’ tips, called hackles, allow the fly to float softly while dimpling the surface. Fishing with dry flies is the most visual of approaches since all the action takes place on the water surface.

A very good first step to understanding dry-fly fishing would be to simply observe insects from a comfortable position on your favorite stream, especially in the cool of the day when they’re more active. A pair of compact binoculars will help. The flitting, diving, incautious aerobatics of flying insects indicates frenzied mating and egg laying. Check the bushes and grasses at the stream edge for insects maturing and drying their wings. Watch closely for any insects that land on the water; you may see exactly what is being eaten and how it is gobbled. Gather an impression of the color and size of these insects as they interact with the surface of the stream. Most of all sense their quiet; you must strive to be just as quiet.

The surface of the water is where birth as well as death takes place for most aquatic insects. The surface is a barrier for the immature insect forms, called nymphs, which live in the gravel and silt on the bottom, and nothing illustrates this better than the lifecycle of the mayfly. As the nymph prepares to become an adult flying form, it fills with a highly light-refractive bubble, and floats and swims toward the surface. It struggles to break through the surface tension and emerge from its shuck, and dries itself enough to become airborne, hopefully without attracting notice by predator fish. Dry flies that sit low in the water in the head-up position represent these emergers.

At the other end of this brief lifecycle, the adult female, after mating in-flight, returns to the surface to lay her eggs. The mating dance of the male typically consists of an up and down gyration from which this stage gets its name, spinner. So single-minded is this reproductive urge that the adult cannot eat, and has replaced its digestive organs with reproductive organs. Exhausted, the female collapses with outstretched wings and depleted body. She becomes an easy meal for the trout, though not nearly as nutritious as the juicy nymph.

Most of the dry flies you use can be easily tied at home, adding more fun to your sport. As you begin fishing tenkara, choose a standard dry fly such as a Parachute Adams. As a “general” fly, it can represent a variety of insect silhouettes. After observing the insect life near the surface of a stream, you might choose something more specific. Never forget what you are trying to imitate.

Start with a #14 hook. If you are used to lure fishing, you are going to be a little shy about using something so small, but the biggest payoff of fly fishing in general and tenkara in particular is the ability to present these small flies without a splashy disturbance, which can spook the fish.

You must plan your approach with care. First, decide where the fish are likely to be holding. Second, patiently and with stealth, place yourself in the best position for the cast. Lastly, while remaining focused, execute your cast and fly presentation.

Let’s look at each of these steps in more detail.

Spotting fish is easy if you can see their “rises,” the dimples or splashes as they feed. If they’re not feeding on the surface, they will be holding underwater. In this case, reading the currents will provide the main clues to finding them. Fish generally will be located where there is a good mix of food and cover. They need to obtain food with a minimum expenditure of energy, thus they will hold at the edges of stream flow where the water carries insects to their waiting mouths. A line of surface foam or bubbles often marks these feeding lanes. Fish will be near these edges, but prefer to hold in the slack water deflected around rocks, logs, and ledges, places where they don’t have to swim hard while they wait. Fish also need nearby cover to which they can retreat if threatened. When there is a combination of a ready supply of incoming food and good protection from current and predators, these spots are called “prime lies.”

Prime lies may be obvious, like the cushion of water in front of or behind a boulder or just out of the current behind a fallen log, but they may also be depressions on the stream bottom, which may give no visible clues on the surface. Polarized sunglasses can often reveal underwater hiding places. Analyzing the current deflections, projecting the slope of banks into the bottom topography, and reconnoitering the shadows of lurking fish from a high vantage point are all ways of stalking fish. In nature one should always think in terms of “edges.” However, sometimes the only way to test water is to fish it.

Before you make your first cast, pick the spots from which you can reach your target with a cast. There is generally a best placement if you think it out. It is generally easier to approach from downstream, as fish by their nature will face into the current. There are times though when approaching from upstream makes sense, for instance when overhanging brush make an upstream cast unlikely. Try to select a spot that is at least partially camouflaged and in shadow. Can you utilize boulders and brush to break up your silhouette? Keep your profile as low to the water as you can, kneeling if necessary. Keep the sun at your back if possible, effectively blinding the fish. Be careful your shadow does not fall over the fish though. Approach with slow patient steps like the stalking heron; sudden moves are the sign of an unfocused angler.

It is wise to plan not just the first cast but how you will move upstream through each section of stream or beat, casting to each likely spot. Can you deliver the cast from the bank or must you risk disturbing the water with a gentle wade? Plan to reduce wading if possible; fish can sense vibration in the water. If you must wade, do so slowly. Any wavelets you can see on the surface can be felt below. Plan your route so that you cast to each likely spot at least three times without spoiling the next. Minimize movement and cast to several lies from the same spot.

Plan how you will deliver the cast. Is there enough room? What kind of cast will be best? Plan to cast above the fish or a suspected lie so as to present a settled fly. How far above depends on the speed of the current, the depth, and visibility in the water. Where is a fish likely to bolt when hooked? Where is the best place to attempt to land him?

After arriving at your casting spot, again visualize the entire path of your cast from beginning to landing. Nothing is worse than focusing so intently on the target that you aren’t aware of the tree branch behind you. Plan your backcast too.

Choose your target, ahead of and to the side of your suspected fish. Focus on the one piece of water, no bigger than a floating paper plate, where you want the fly to land. Consider starting your cast with a smooth exhalation, just like a marksman pulling the trigger. The first cast to a spot is always the most likely to stimulate a bite; make it a good one. It is much better to hoard your casts, fishing few but more precise casts, than to cast repeatedly. Be ready; fish most often take a fly soon after it lands.

Nearby current that is faster than the water in which the fly is drifting can ruin your presentation. Try not to let the current grab your line and tug the slower-moving fly. A dragging fly with a wake does not resemble an insect. A high reach and a light touch that leaves neither too much line on the water nor takes up all the slack will help avoid drag. Tenkara rods, with their long reach, enable you to keep everything but the tippet off the water. More than the western “high sticking,” tenkara actually allows much longer line lift. (For instance, assuming a conservative right angle between rod and line, a thirteen-foot tenkara rod could keep eighteen feet of line off the water compared to twelve for a nine-foot rod. The contrast is made even greater when considering line weight sag and the strain of holding an extended western rod and reel for long hours.)

Try to keep any line on the surface in water moving the same speed as the fly. This means casting upstream or slightly across stream and keeping your tip elevated as you follow the fly. As the fly drifts downstream, adjust the amount of slack by raising and lowering the rod tip.

If your focus is good, you will constantly observe the water around the fly as you keep it in your field of vision. You may see the flashing silver of an interested fish nearby, or the white of his mouth with a take. Sometimes a fish shows interest by breaking the surface behind your cast, as if to ask, “What was that?” Show him again.

As a fish takes your fly, you will often be surprised at the vigor with which it breaks your reverie, launching from below and splashing explosively. At other times, it may be a sipping take, mere lips breaking the surface then running deep with its meal. Either way, you must be ready to lift your rod like a flag with a crisp snap of the wrist, capturing your quarry and rewarding your stream craft, stealth, and focus.

The dry-fly cast encompasses the essentials of tenkara fly fishing, though I must confess that tenkara wet fly or subsurface fishing is, in fact, more traditional and perhaps more productive. (We will explore subsurface fishing soon.) In fact, certain dry flies can be fished wet as they become soaked, with great effectiveness.

Remember to execute mindfully. Athletes may recognize this as “being in the zone.” Your prize will not only be plenty of exciting fishing but the disciplining of the mind as well. The distractions of the world and the ego will often evaporate, leaving room for clarity and confidence and, most of all, great fun.

In Japan there is a much-prized aesthetic called wabi sabi. Wabi implies, first and foremost, a simplicity through which a person obtains a degree of harmony, balance, and understanding of their place in the world. Its meaning is rooted in a sense of spareness, almost poverty, in which one finds contentment in the most basic of possessions, an acceptance of imperfection. Through this simplicity one is able to experience a sense of peace and, most of all, authenticity. Sabi is the character of natural materials that show signs of the aging process and the mark of time. It reminds us of the impermanence of all things. When tenkara is approached with simplicity, mindfulness, patience, and an appreciation for the natural environment and our place within it, it is certainly wabi sabi.

When, after a patient stalk, your dry fly softly lands within inches of the placement you visualized, drifting without drag across the cool shadow of a prime lie, then you have already landed the prey you seek.