IN THE WOODS, TOO, A MAN CASTS OFF HIS YEARS, AS THE SNAKE HIS SLOUGH, AND AT WHAT PERIOD SOEVER OF LIFE IS ALWAYS A CHILD.

—Ralph Waldo Emerson

One of the strengths of tenkara lies in its cast. It’s so simple that in a short time you will be able to execute it without thinking, allowing you to concentrate on the approach and presentation.

A beginner can use a tenkara rod to place a fishable fly immediately without instruction. (In fact, no instruction is often a better approach if you are introducing a child; just let them fish without critique.) However, a bit of thought about casting and a little practice can make your tenkara experience more fruitful. This chapter will show you how easily you can accomplish this.

A western fly angler will want to compare and modify his or her cast for tenkara. You may never have held such a light and responsive rod before. If you are an experienced angler, expect to overpower a tenkara rod at first. The cast of the tenkara rod is different because of its slower action and its length. As a general rule, all your casting movements will be briefer and less vigorous than with a western fly rod. In contrast to western fly casting, very small wrist and forearm motion is often all that is needed. The abrupt stop or flick at the end of the cast, however, remains important, just as in western casting. Work with the rhythm inherent in the rod. Wait on it. You’ll be surprised at how smoothly and efficiently you can cast if you allow the rod to do the work.

Since the tenkara rod is so much lighter, the grip is chosen more for accuracy than strength. Placing the index finger along the backbone of the rod or slightly to the side will help develop accuracy and restrain the delicate tenkara cast. It is through the pointed fingertip that tenkara gets much of its precision and uniqueness. As in western fly fishing, you will want to involve your forearm in the motion; however a more relaxed and smaller motion is all that is needed. In fact, the motion of a tenkara cast is often mere inches. With such a lightweight rod, you will be able to cast for a longer time with less fatigue. You will find yourself being able to flick the fly with just a quick hand movement. “Choking up” on the grip or even onto the rod proper can aid accuracy as well as shorten the rod for tight casting. Keep your arm and grip relaxed. Any tension reduces accuracy.

Some tenkara anglers like a “v-grip,” which involves moving the index finger off to the side, forming a “v” between thumb and forefinger, with the forefinger pointing down the backbone of the rod. This adds power to the stroke. The placement of the grip can also vary with the direction of a given cast.

A balanced stance is helpful in a good cast, but most anglers will do this automatically. When extreme precision is important, tenkara masters often lead slightly with the right foot (for right-handers) helping to aim the rod, thus keeping the trajectory more on line with the arm and the path of the rod. This is called a “closed stance.” At its most accurate, the path intersects the fisherman’s eyes mid-forehead. With the non-casting arm counterbalancing, hand-on-hip, this tenkara position closely resembles the en garde stance of a fencer. When learning, an “open stance” (left foot leading) allows the student to watch his line more easily. Crouching and kneeling are likely positions when fishing too. On the water your stance is more likely determined by the stream. Keep your stance relaxed and yet athletically poised, the stance of a hunter.

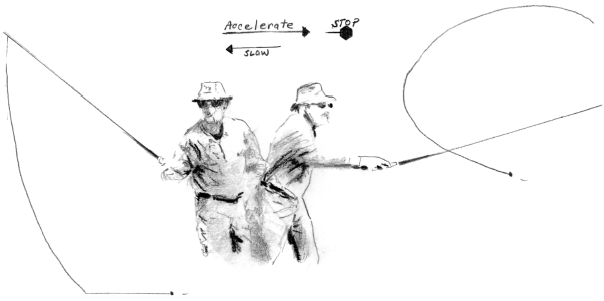

Remember that the cast primarily does one thing: The flex of the rod pulls the line behind you, then a reversal of this flex pulls it forward again toward the target. The best way to feel this is to simply try a back and forth sidearm motion. You can see how the line forms a loop and then straightens. To better visualize the cast, Misako suggests trying this sidearm casting with yarn attached rather than line. The important thing is to sense this very fundamental back and forth motion. Don’t go too fast . . . wait briefly on the backcast to straighten before accelerating forward. This pause is very important. Keep a relaxed grip and work with the rod. Watch as it bends with the load, then releases its energy as the line unrolls. Get a feel for the flow of this motion.

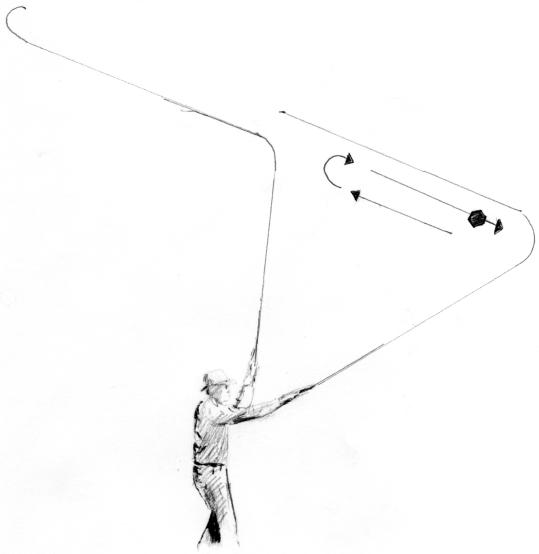

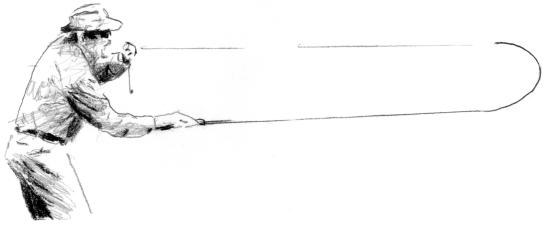

When casting with a tenkara rod, I think it is useful to try to think of moving the tip back and forth around a thinly stretched oval. Go under the oval on the backcast, and over the oval on the forward cast. At the end of the oval, as your rod tip moves toward the target, stop the rod by a brief flick of your pointing index finger. I like to tell students the index finger movement is like scolding the fish. You will see that the line is cast in the direction the tip was moving when you stopped it. This brusque stop of the wrist and arm is what sends the line toward the target. Fly anglers don’t cast by pointing the tip directly at the target (like spin anglers) because the tip bends so much. Instead stop the rod while still pointing slightly sideways. I like to compare it to flicking paint on a wall out of a loaded paintbrush. The stop does not have to be hard, but you will find that a full stop with a light squeeze of the grip is best for extended and accurate casts, especially when casting longer lines.

Because the fly is going to end up in the water (we hope), the backcast should be inclined upward by varying degrees. The angle of the backcast is generally higher than with a western rod due to the short line. This is very helpful in avoiding snagging brush. If you do find your fly catching in the flora, angle the backcast up even more.

Gently lift the line from the water and fling it backwards and slightly upwards. After a brief pause in which the line straightens, start the line forward toward your target, stopping your hand once it has the proper momentum, flinging it home. Err on the side of gentleness. Can you feel the smooth application of the rod’s bending? Can you see how it does most of the work for you?

Even young anglers can figure a tenkara sidearm cast out within a couple of tries. With practice, the sensation of loading the rod with the weight of the line will soon become second nature, as long as you do not try to force your cast.

Sidearm casting is one of the most useful casts. With its low profile, fish do not easily see it. It fits nicely with an upstream casting plan as you walk along the stream bank, placing most of the cast over the water instead of in the trees. For this reason, if you’re a right-handed caster, choose the left bank as you make your way upstream.

I use a sidearm cast frequently to dry a fly that has become soaked, making several vigorous false (back and forth) casts. False casts with tenkara rods are much less likely to whip-crack than with stiffer western rods, so don’t be afraid to give it a bit of snap to dry the fly out. False casting over a fish is a sure way to spook it, however. Dry your fly in a different direction.

While the sidearm cast is the one that the tenkara angler will use most often, there are a couple more casts you will find useful.

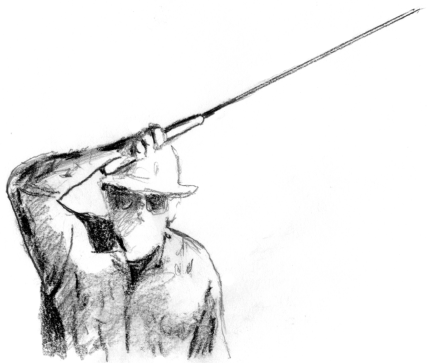

Tenkara fishermen in the mountains of Japan traditionally have relied mostly on the overhead cast. This cast is flicked above your shoulder and head and then forward on the same line to the target. It is useful for placing your backcast high above streamside trees. It can also be very accurate.

If you are trained in the “clock face” approach to western fishing, the overhead cast occupies only the wedge from ten o’clock to noon, maybe less. The backcast is composed of a fairly steep and quick pull upward, using the forearm more than the wrist. This resembles the backcast of the western steeple cast. The forward motion is much abbreviated and pulls the line over the top of a very thin oval. Try to keep the line moving along the same trajectory. The loop that is formed as the line goes back and forward is tighter when the cast is on line. A tighter loop is a more accurate loop, and if a loop is narrow it is less likely to catch on things.

However, it is also useful to sometimes break this rule and change the direction of your cast. Although not as efficient, such a cast can help place a fly when there is no clearance immediately behind the target. Also you may want to quickly place your fly off line if you suddenly spot a fish rising.

If the rod is directed with a sharp stop, the loop will be tight and less affected by wind. A more arched cast results in a larger loop and a slightly softer cast. The angle varies a bit depending on how far or near from you that you want the fly to land. A more open loop is useful for softer presentations and a brace of more than one fly, just as in western fly casting. Tight loops can throw longer lines and heavier flies.

If the stop is too vigorous, however, you may find the rod tip bouncing back so abruptly that the line piles and shortens the cast. You want this stop to be firm but not jerky. Remember, aim your index finger and squeeze the grip gently; a little bit of abruptness goes a long way. With a short tenkara line, you can tuck a fly into the water nicely with little effort. Use your index finger like an orchestra conductor; there is a delightful rhythm to the tenkara cast.

Tenkara fishing in Japan traditionally uses a wet fly in the fast, broken waters of mountain streams. In this case a fairly hard landing is useful for attracting fish and breaking the surface tension, allowing the fly to sink more easily. In quiet or still water, and especially with dry flies, a softer landing is better. Aiming your fly at a spot a foot above the surface will give you a softer presentation.

The backhand cast is simply a way to cast on the opposite side of your body. The backhand cast in tenkara fishing is slightly different from its western cousin. It does not need as long a stroke. On the backcast, the hand is raised toward the opposite shoulder such that the forearm and forehead almost touch, thus casting on the other side of your body. The forward stroke attempts to present a straight line from the backward stroke, using, as always, a flicking index finger.

A backhand cast is very useful when wind is coming from the casting side and you want your fly and its sharp hook to stay safely downwind. It is also necessary when wading upstream on the “wrong side” from your dominant hand. A backhand cast is useful in presenting a fly to some more difficult lies and is a sign of a practiced fisherman. Of course, as an alternative, you may want to learn to cast with both hands, which is surprisingly easy with a tenkara rod.

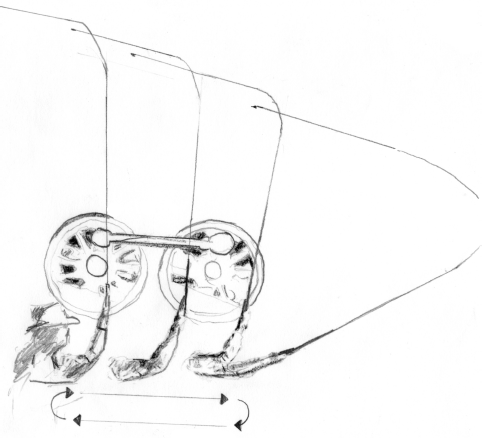

When an angler has little room behind him for a backcast, a roll cast is often the way to go. Since tenkara lines are relatively short compared to western rods, this cast is almost always executed with a sidearm motion. As the fly is fished back or lifted slowly toward the angler, and while the line still has some contact with the water, simply load the rod with a slight up-and-back pull, using the water to anchor the end of the line and fly, then accelerate toward the target, ending in an abrupt stop, flicking the fly toward its target. The water contact helps to load the rod and should be roughly on the same line as the target.

The tip follows a slight oval or roll, important in order to keep the line from tangling. Remember to aim nearly parallel with the water, not in a karate-chop down motion. With the roll cast you must wait for the line as it unrolls toward the target. Since there is only moderate loading, you will sacrifice distance, unless the casting stop is particularly strong and abrupt.

By the way, a quick and forceful roll cast, sent past a snag, can sometimes loosen a snagged hook in the water. Make your forward roll past the snag, as vigorous as you can manage; this maneuver is not as effective as with a western rod.

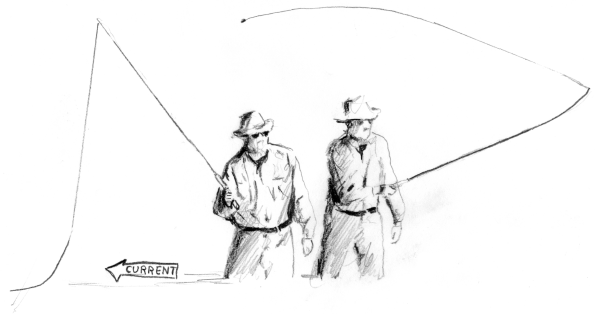

At the beginning of a lob cast, the current of the water is allowed to pull the fly downstream until there is some tension or drag on the line. The rod then tugs the fly against the current, flipping the fly in the upstream direction. Because of its low profile, this cast is especially effective in the wind. It’s a cast that always takes less effort than you’d first expect, and is done with a very relaxed motion. It is my favorite tenkara cast because I enjoy the way the entire line extends upstream with so little effort. With practice you can cast in either direction.

With heavier flies this cast becomes even more of a lob, as the added weight loads the rod. If you’re using droppers or indicators this is the ideal cast to prevent tangles, and is perfect for short-line nymph fishing and Euro nymphing. (More about this later.) Of course, it takes a little more muscle to cast heavier flies.

Sometimes called a slingshot cast, and known in Japan as yabiki, the bow and arrow cast is very useful when the brush is particularly tight. I often use it as the first cast of the day. It’s a quick way to just get the fly on the water. The line is gathered in a couple loose loops in the non-casting hand (about eight inches is a good size for the loops) pinching the line between thumb and finger. (For shorter lines, just pinch the tippet above the hook without loops.) The rod tip is pulled back, forcing a strong bend on top of the rod, with the rod tip and tensioned line above the rod shaft. A smooth release will result in a surprisingly effective fly placement. If the hook is hanging below your pinch by no more than eight inches, you won’t risk getting snagged. If you are familiar with this cast using western rods, you will be surprised by how much more efficient tenkara rods are.

For an underhand cast, the oval of the cast’s path is in the opposite direction from a more conventional cast. You simply load the rod into the backcast over the top of the oval and let the fly go on the bottom of the oval, like an underhand softball pitch. A variation is the tension-swing cast. Misako, inspired by Bob Clouser’s oval casts (in which he maintains rod loading over an oval path), uses this variation for very accurate placement under brush. The tip of the rod, held to the side (anywhere from forty-five degrees to a few feet above the water), is simply pulled backwards in a straight line from the target, allowing the fly line to follow under the rod tip. Stop the rod tip with a brief pause while the line extends behind you.

The rod tip then moves on a straight path forward toward the target, pulling the line and fly underhand. The line never goes over the top of the rod. The fly is dropped to the target at the apogee of the forward swing. The line stays below the rod throughout the cast, closer to the water. A little touch is needed to swing the fly in low, and a feel for this cast requires a little practice. With the innovative tension-swing cast, the path of the fly is very narrow, often just a few inches below the rod, and can be used to avoid obstacles that would obstruct other casts.

Acknowledging that the traditional tenkara cast has been fine-tuned over several centuries, it may be wise to emphasize the appearance of a tenkara master casting on the stream. With intense focus and awareness of streamside camouflage, the master places a precise overhead cast into the seam of current or eddy. His backcast is high, thrown over his shoulder and head. His forward cast is accomplished with a brief and precise thrust toward the target. He lands the fly with a bit of firmness that sinks the fly through the surface tension, allowing the fly to sink to the desired depth. By pulsing the tip of his tenkara rod, and as his intuition dictates, he adds lifelike animation to the reverse hackle fly. The drift spent, he tugs the fly against the water tension, sending it over his shoulder for his next cast. Throughout he remains balanced and ready to set the hook.

Tenkara allows for endless variations to the cast, of course. Over time, you will find yourself developing your own casts, unique to your height, strength, fly and rig weight, and home stream characteristics. Though knowing these seven casts might improve your ability to cast in many different situations, the idea is still to simply get a fly to the fish. They don’t really care how it gets there. Because all the tenkara variations are so simple, you are allowed to keep your mind on accurate placement, which is, in fact, more important. Intuition will take over if you allow it.

If you are used to casting with a western rod, the adjustments to tenkara really are minor. The casts are basically the same. You will find though that after fishing with a tenkara rod a while, your western fly casting will improve too. Because the tenkara rod must load the rod with the stroke itself, hauling a line is not a method used to overcome casting faults. The next time you cast your western rod, you will notice you are loading it more efficiently. Tenkara makes a great training aid and is a fantastic way to introduce someone to the essentials of fly fishing.

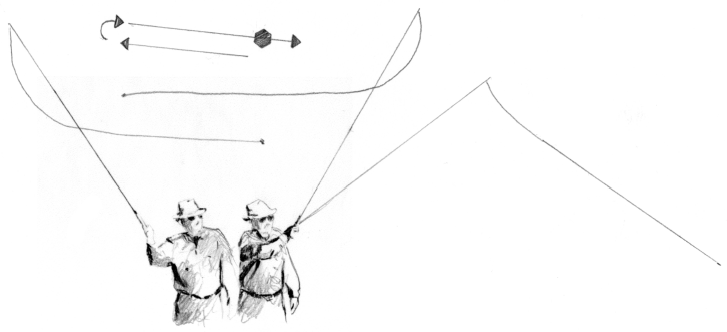

As your casting gets better, and particularly on larger waters, you may want to extend the length of the line you are using for greater reach. Maintaining line tension throughout the entire cast becomes a very important concept when casting a longer line. Italian fly-fishing master Roberto Pragliola describes the efficiency and accuracy of the tight-looped cast, which he calls T.L.T. casting (Tecnica Lancio Totale, or Total Casting Technique). At the end of your backcast, your casting arm drifts up a bit. This inscribes the first half of the oval. As the forward cast progresses, the arm extends forward and rotates down a bit before coming to a stop, allowing one to cast the line to full extension. Think of the pattern inscribed made by a drive-rod on a locomotive wheel.

Keeping a bit of tension throughout the cast may bring to mind the Belgium cast, which is essentially a constant-tension cast that starts as a sidearm cast and ends as an overhead cast. The tenkara cast has many of the attributes of this cast, albeit with a smaller oval. Sometimes the oval is so narrow it is hardly recognizable. Other times it is wider and more obvious. For greatest efficiency, the legs of the oval should remain parallel. With increased tension and using a longer fluorocarbon level line, Dr. Ishigaki will cast up to twice the length of the rod, extending the reach of the tenkara rod over thirty feet. Thinking in terms of this oval in your casting is sure to improve your distance and line extension. However, short-range accuracy remains the strength of tenkara.

As you explore the tenkara cast or as you transition from western fly casting to tenkara, keep in mind the basics:

Don’t overpower your casts: Tenkara is a restrained, even gentle cast.

Tighter loops mean more control: Tighter loops are formed when the arm movement is brief and brisk, and the backcast and forward cast are on the same line. “Flick that paintbrush.”

The fly goes where the tip points: At first, aim the whole length of the rod rather than focusing on the tip; as you become more experienced you will develop “tip awareness.”

Lift up your backcasts: By aiming backcasts with at least some elevation, the angler keeps his line from dropping on the water or catching on the grass behind. An elevated backcast also allows for a slight, downward angle on the forward cast. The closer you are to your target, the higher you should elevate your backcast.

Stay balanced and relaxed: By remaining lithe in your motions, neither too rigid nor too loose, you will tire less readily and be more accurate in your cast. A stable stance helps. Tension blocks the flow of energy from your feet, through your arms, and all the way to the tip of the rod.

Practice accuracy: Aim at a distinct target with every cast. Practice precision. To fish most effectively, accuracy is essential, and is the primary skill that characterizes the accomplished angler.