ONLY THOSE WITH PATIENCE TO DO SIMPLE THINGS PERFECTLY WILL ACQUIRE THE SKILL TO DO DIFFICULT THINGS EASILY.

—Johann Schiller

Aquatic and terrestrial insects are on the menu for any trout stream. Observing the chef’s special will go a long way toward enticing fish to your fly. Sampling the brush with your hat, and the water and bottom with a seine or fish-tank net, can bring you samples. I stretch a simple cheesecloth bag over my fishing net, and then stir up a little of the streambed and lift a few rocks upstream. If you haven’t tried sampling a stream bottom, I think you’ll be surprised. You don’t even have to know what the insects are, just the location, size, shape, and color.

Aquatic insects go through such a predictable lifecycle that hatches can often be predicted by date and even hour. Furthermore, each insect prefers a specific temperature, light, and humidity to trigger its hatches. In early spring, hatches (and hence fish feeding) don’t begin until the water warms up. Later in the season, as a general rule, the heat of midday shuts hatches down. A degree of air humidity allows insect wings to dry a bit slower and is preferred by the emerging adults or duns. Hatches therefore are often most prolific on cloudy days, and near dusk or dawn.

Depending on the water type, late summer fly choices are typically biased toward the terrestrials, including ants, beetles, and grasshoppers. This is especially true in streams with depths that vary with rain runoff and that border grassy fields and meadows or have a lot of overhanging brush.

Tailwaters often favor the tiny chironomids, or midges, which hatch in abundance from this water. The water temperature is stable and the water fertile. Yet studies have shown that it is the midge’s ability to survive the drying out periods and wide variations in water depth that most favors them in these waters.

The weed beds of lakes and streams may harbor freshwater shrimp and scuds, as do tailwaters with lots of aquatic vegetation. Likewise, feeder fish stay near cover and prefer shallows.

Some anglers make such a serious study of insects that they rival professional entomologists. “Matching the hatch” is a time-honored approach to dry and emerger fly fishing. A little knowledge of insect prevalence can’t help but improve your fishing, whether you are matching a quilled dun or just making whatever fly you have on hand skitter a bit in imitation. When sampling, choose the most active and most frequent insect specimens to imitate.

The following pages contain a very brief guide to identifying common aquatic insects to get you started:

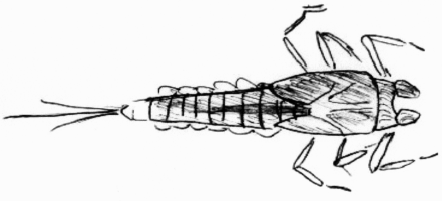

Mayfly nymphs usually have three tails (though some have two), but always have gills along the side of the abdomen. Mayfly nymphs range from 3 to 16 millimeters long and cannot tolerate pollution or high temperatures. They swim with a quick, porpoise-like motion. Colors include black, gray, and brown, with dark wing pads prominent over the thorax.

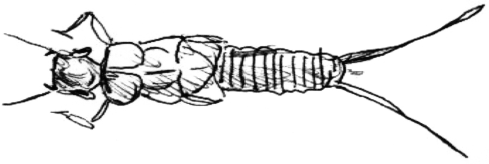

Stonefly nymphs are generally large nymphs growing up to 60 millimeters. They have two long tails that they retain as adults and two prominent antennae. Their gills are on the thorax below the legs like hairy armpits. These clumsy-looking nymphs climb on streamside rocks to mature. Their oxygen needs are great and they require fast water without pollution or silt, thus their presence indicates excellent water quality. Most are shiny brown or black but can be light tan.

Damselfly nymphs are easy to identify with their three large paddle-shaped gills at the tail end, which they often wiggle to help oxygenate. Their large compound eyes are prominently black against their brownish body. Their grasping jaws help these carnivores grasp their prey.

Dragonfly nymphs are jet powered, expelling water for squirt propulsion. Brown or olive, these large (20-50 millimeter) wide flat nymphs molt on streamside vegetation and boat docks. They have prominent compound eyes and are found in aquatic vegetation where there are slow currents.

Caddisfly larvae look like small caterpillars, varying from brown to chartreuse to cream, usually with a darker head and shoulder. Many make protective cases from tiny gravel and vegetation, and some make weblike nets to catch food. They are tolerant of warmer water.

Midge larvae, also called chironomids, are tiny, wormlike, thin, and segmented. The red ones are especially tolerant of lower oxygen levels because they have a compound like hemoglobin, so they can be found in silt. Their darker gut-line can usually be seen, especially in the light green and clear larvae. They are very active, wiggling the ends together, burrowing into river mud and the bottom of ponds.

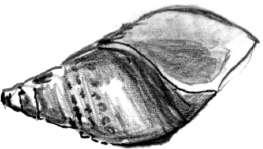

Snails of course are not insects at all but are gastropods. They are present in quiet water, especially on lakeside vegetation where they are common meals. Snails whose “door” opens to the left (with cone point up) have lungs, which tolerate oxygen-poor and organically thick water. Those that open to the right (illustrated) have gills, which require cleaner and better-oxygenated water. Left=lung=lousy.

Scuds, commonly called freshwater shrimp, are another invertebrate that swims rapidly on their side. They are mostly clear but pick up the color of their scavenged food: tan, pink, and green. They live in the aquatic vegetation of calm water.

Water striders have tiny grooves in the legs that allow them to easily walk on water. They cannot detect movement above or directly below them so they are easily observed and are easy prey for fish. They can detect surface vibration easily, however, and locate food this way.

The dobsonfly nymph, or hellgrammite, is large and easily identified by its pinchers and armored appearance. Living between rocks, it preys on other insect larvae. Both the larvae and adult are nocturnal but are attracted by lights, with the adult often growing to five inches in length.

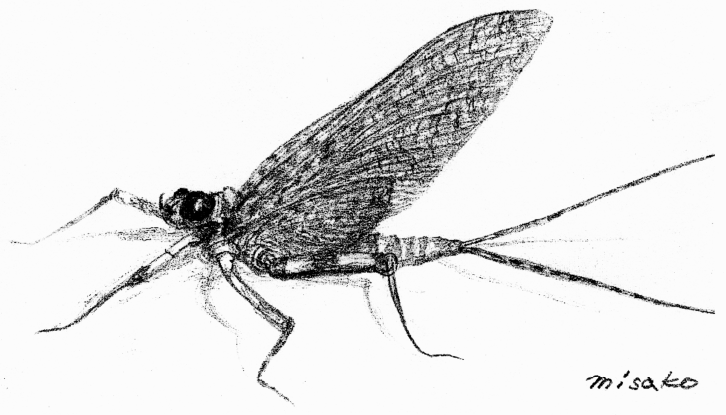

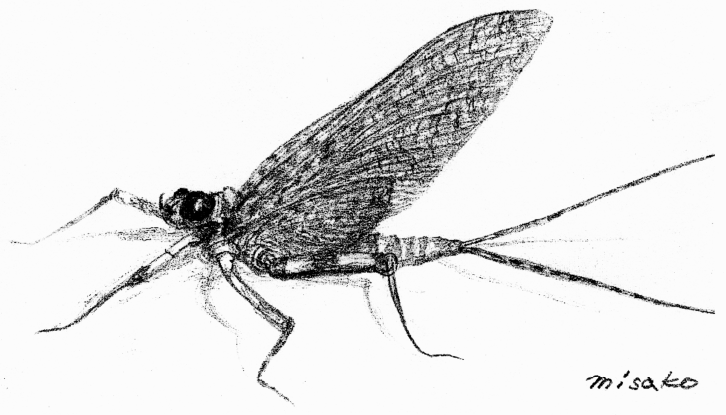

Mayfly adults have two stages: duns, when wings are a dull opaque and have a mottled appearance, and spinners, when the wings are translucent and lighter colored. Hatches enable large masses of mayflies to mate quickly, as the adults live only a day or two and do not feed at all.

Caddisfly adults look like moths in their fluttering flight. They are attracted to light, so they can be seen around dock lights and streamside cabin windows. Adults live for weeks and can mate several times. Females deposit eggs on the water surface and streamside vegetation, though some submerge, “gluing” their eggs to the bottom gravel and staying below up to thirty minutes.

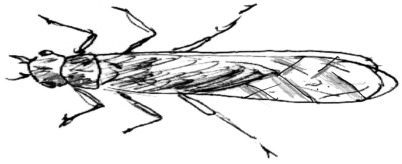

Alderfly adults look very similar in size and wing position to the caddisfly, but can be distinguished by its shorter antennae and darker coloration. It lives on stream side brush, and is a much poorer flyer. Its nymph has a single “tail.”

Stonefly adults are clumsy fliers looking a little like dragonflies in flight. Their wings fold flat against their back and the veins give the appearance of a hair braid at rest. You see stoneflies in the book and movie A River Runs Through It.

Aquatic moths are important evening and night foods fluttering actively along stream banks. Their cream to tan colored delta wings leave dusty scales if captured.

Midge adults are small, prolific insects that can be found year-round. They comprise a surprisingly large percentage of fish diets. They often are seen in mating clusters on the water surface, and can be present in large numbers. They can often be seen covering streamside vehicles (they have a predisposition toward white and yellow paint).