GOD NEVER DID MAKE A MORE CALM, QUIET, AND INNOCENT RECREATION THAN ANGLING.

—Izaak Walton

To fish effectively, most anglers will find a dozen or so flies that work consistently, and keep gravitating back to them. A few professional fly fishermen use a single fly design. Western fly fisherman Rim Chung, for instance, likes his own emerger design, the RS2. Tenkara fisherman Dr. Hisao Ishigaki fishes a simple reverse hackle fly. The very best fly fishermen learn how to use a few flies well. Keeping your fly selection simple makes on-the-water decisions easier and is in keeping with the ease of tenkara fishing. It is tempting to start by buying a number of different flies when you are a beginner, but you will find yourself simplifying later. Why not start with just a few proven designs and learn their history, their uses, and how best to present them? Better yet, tie your own.

Tying your own flies is not difficult, and catching fish on flies you’ve made yourself adds a whole new level of enjoyment to the sport. After factoring in the time spent, you might not be saving much over discount house flies, but the ones you make for yourself are usually of better quality. You might even decide to tweak the standard designs to come up with your own unique “magic” fly. Fly tying can be a very enjoyable hobby unto itself.

You can start tying flies with very little investment. Given that specialty tenkara flies may not be readily available at your local tackle dealer, it makes sense to start tying your own. If you make a fly or two following the instructions below, you can get a feel for fly tying and may want to spend another thirty to forty dollars on a vise and thread bobbin, the only two pieces of equipment really needed to tie flies regularly. This experiment is just to give you insight into fly tying, which is often viewed as difficult and esoteric. (You may not want to fish this first effort. If you do become a fly tyer you will appreciate saving your first fly.)

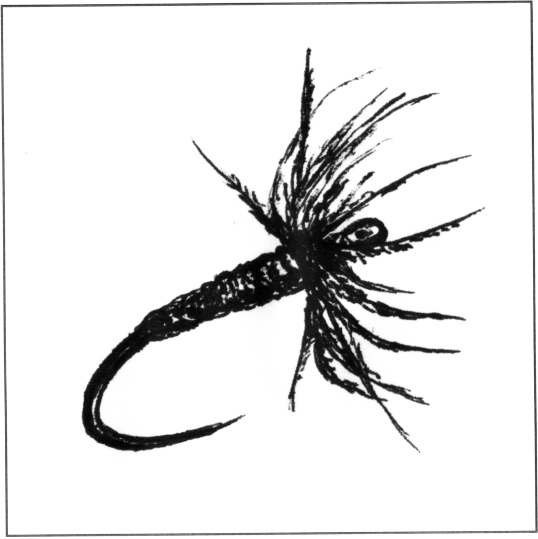

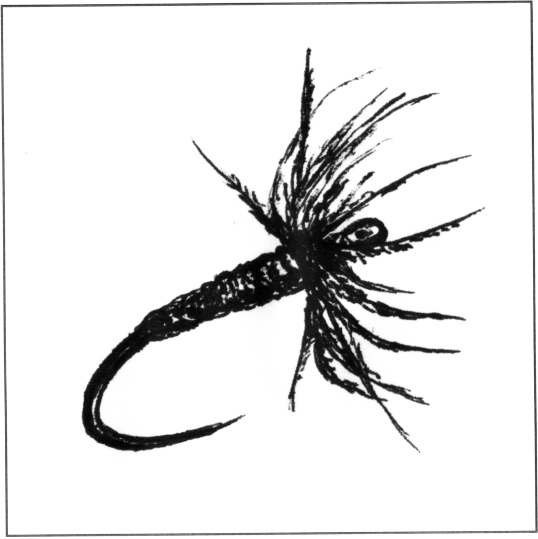

A traditional reverse hackle tenkara fly is one of the easier flies to tie, and since it can be fished as a dry fly or wet fly it is very versatile.

Clamp a bare hook (start with a #12 dry-fly hook) in your fly-tying vise. If you don’t have a vise, clamp the hook in your hemostat and attach it firmly to the edge of a table using a C-clamp.

Collect a feather for your hackle. Hen hackle is fine but any small and thin feather collected in the yard will work. The barbs should be about one and a half times the width of the hook gape, the distance between shaft and barb. Pull off any fluff at the base of the feather and use your finger to fan the barbs slightly.

Tie ordinary sewing thread to the hook by wrapping the shaft of the hook with thread in one direction, then over-wrapping it back in the other direction. Hold the spool in the palm of your hand and direct the turns with your index finger and thumb. Trim off the tag. Cover the hook with thread to the point on the shaft where you want to place the hackle, usually one-third of the distance back from the eye. Avoid catching the barb by wrapping at a slight angle.

Now tie in the feather by holding the tip of the feather against the hook shaft, concave side up, and wrapping it with three or four tight turns of thread. Trim off the tip excess with scissors, and wrap thread over the trimmed tip to hide it. The thread on the eye side of the feather will represent the head, so feel free to add a little extra thread to shape. When done, wind the thread behind the feather attachment point toward the hook bend.

Now, holding the feather firmly and with constant tension (but not pulling too hard), wrap it four or five times around the hook shaft. The wraps should be very close together. This next is the hardest part and takes a little hand changing to keep it tight. While holding the turns firmly, tie the feather off behind (on the hook-bend side) by again over-wrapping the feather shaft with thread. Wrap it three times, then trim the excess feather. Keep it tight. A few extra turns over the excess hackle is done to hide the end.

Now pull the hackle, bending it with your thumb and three fingers, winding the thread tight against the wound feather hackle, overwrapping it a bit so that the hackle tips point toward the hook eye. This leans the hackle forward in its distinctive reverse hackle position; the amount of lean is up to you. (See Misako’s drawing at the beginning of the chapter.)

Finally, finish by wrapping thread around the hook shaft all the way to the bend of the hook. Then tie off your thread with several overhand knots. Cross the thread on itself with a twist of the fingers, placing the knot at the end of your thread wrap at the beginning of the hook bend, and pull it tight. Trim the thread closely. You can make it more secure with a dab of nail polish or waterproof Super Glue.

Interested in making your own flies regularly? A good bobbin (I recommend one with a ceramic tube that won’t fray thread) is only ten to twenty dollars. A very usable vise can be had for not much more. The vise should hold a hook firmly and either have a heavy base or clamp to a table, nothing more. The ability to rotate is strictly optional.

Start by purchasing enough materials to make a couple of proven flies. Practice these before experimenting with your own designs. Buy hackle of good quality for dry flies; the so-called generic hackle is pre-sized and makes selection easy. There are many good books on fly tying and thousands of patterns are available online, many with easy to follow videos. It takes tying a dozen flies to learn a single pattern and to get a well-proportioned fly. Joining a “fly tie” session at a local fishing club is a way to get valuable critique and advance more quickly, as well as make friends. Fly tying can become an obsession unto itself, so be careful.

If you would rather purchase some of the traditional kebari flies, there are a few U.S. suppliers on the Web.

On most waters, the fly is less important than the presentation. However, you will be surprised by how often fish will have nothing to do with one fly but will be hungry for another. You will develop preferences as to how you like to fish, which will influence what flies you carry. Of course, the type of water you are fishing will influence your choices too.

Choosing a fly is part deduction and part guess. Early in the season I prefer larger and darker flies. “Dark flies on dark days” is a time-honored aphorism. There is a general progression, following the colors of spring, from gray-blue flies, to browns and olives, and finally chartreuse and yellows. Misako likes a bit of white at the eye end of her soft hackles. I often favor a small tag of green or red/orange on streamers and larger nymphs. Brighter and larger flies should be more effective in stained water while more natural-colored flies are used in clear water.

When you fish unfamiliar water, asking advice at a fly shop and then buying a half dozen of their recommended flies is always a good idea. Local knowledge should never be ignored.

Hiring a guide is almost always worth the investment. Tell the guide up front that you want to learn, not just fish, and she will help you tap into her own intimate experience with the local waters. Make clear to her that you are fishing with a tenkara rod, and what that means as far as reach. It may be the first time they have heard of tenkara.

What are my favorite flies? I have always been a sucker for buying and tying flies the “experts” think are the best, and so my preferences change like the weather. If you ask me the same question in a year, the answer is liable to be different. Fly preference seems to be based more on experience than science. For example, I asked four experienced tenkara anglers their favorite dry fly for mountain streams, and got four different answers. My West Coast consultant favors the Al Troth Elkhair Caddis. My Arkansas connection, the Fran Better’s Usual. New York waters favored the Hans Weilenmann CDC and Elk, and in the Blue Ridge, Lee’s Royal Wulff was praised. All are high-floating, easily seen flies, which may be their most important attribute. All work, and I believe these anglers would do nearly as well with any of the other choices.

Furthermore, most of my fly choices reflect my Blue Ridge and Appalachian home waters. When I fish out west my fly choices change. Your home waters may require something completely different in turn.

So when considering which flies to put in your arsenal, first think of how you will use them and what they will represent. Then simplify your selection as much as you can. Don’t carry so many flies that you will get confused on the stream and spend more time changing flies than fishing.

When I am fishing late winter/early season water, I favor nymphs and streamers. I like a weighted Gold-ribbed Hare’s Ear, the Zebra Midge Nymph, and Woolly Buggers in black and purple. I will often fish a Bugger followed by a nymph, a great searching strategy on medium-sized waters. Because colder water makes fish sluggish, you must fish the bottom slowly and expect subtle bites. Generally, an indicator is needed to do this well.

As the days warm up I start to experiment more with dry flies and emergers. When water temperatures warm to 50 degrees you’ll see me trying a Parachute Adams, Royal Wulff, and Elkhair Caddis. A Partridge and Orange wet or sakasa kebari (brown on black or grizzly on red work best for me) are fun wet fly additions and imitate emergers on the Jackson River. If I fail to see rises, it’s back to nymphing, now with faster sinking bead-heads. The Red Squirrel and Olive Bead-head are my favorites, though I add a thread “vein” on the dorsum for luck when I tie them. A tiny Zebra Midge under a dry fly indicator is my standard tailwater combination in spring, except in faster water where I might use two nymphs.

May is the best month for fishing in the Blue Ridge. Often I begin fishing the lighter colors, like the Yellow Comparadun or the X-caddis in tan and amber. These flies tend to be smaller though, as I work the Smith River hatches. My favorite streams are the small mountain streams like Whitetop Laurel and Big Wilson, where I favor Royal Wulffs and Gulpers.

Summer will see me fishing a Hi-viz Ant pattern, a Black Closed Cell Foam Beetle, and a Madam X Hopper. An Orange Stimulator shows up later in August while a Griffith Gnat and red or black midge patterns are still working on tailwaters such as the South Holston.

Late summer and early fall I generally target smallmouth bass with surface poppers, Woolly Buggers, and hellgrammite imitations. I like the relaxed float of the Gala to Glen Wilton section of the James River, though I’ll admit the largest smallmouth are in the New River, especially near the armory and the Eggleston to Pembroke section.

Sunfishing with a Bully’s Bluegill Spider is a great fly for fishing brush piles, especially around the head of Philpott Lake and while floating Fairy Stone in my canoe. Pond fishing with a popper makes for guaranteed action, especially important when I take my seven-year-old nephew.

Remember that patterns are not as important as presentation. When fishing a pattern, give it a fair trial in a few different spots before changing. Last-minute refusals should be answered with a smaller version.

I must conclude with a reminder. Since tenkara is so new in the United States and Europe, the many adaptations of tenkara are still being explored. Dr. Ishigaki, the most recognized master of tenkara, fishes one pattern in several sizes and colors. Maybe we should take a page from his book. Indeed, a tenkara traditionalist may be dismayed at my mentioning so many western flies. In any case, find out what works best for you on your waters, and let me know. However, in the spirit of tenkara, do try to keep it simple.