THE DORA REVIER. All the concentration camps had some sort of hospital, which was called the Revier. Certain camp maps indicated Häftlingskrankenbau or HKB, which was the same thing. There was a wide variety of Revier, depending on location and time period. The quality of a Revier was dependent on the personality of the SS doctor who supervised it, and that of the Kapo under whose command it fell; it also depended on the genuine medical competency of the “doctor” and nurse prisoners who worked there. In any case, means and particularly medicines were generally lacking.

The setting-up of a Revier at Dora was part of the makeshift conditions of the early months. Initially there was only a tent close to the tunnel entrance, followed by a sort of shanty (Bude) in the tunnel; and finally, one of the first blocks to be built in the camp—on the north side of the valley, no doubt Block 16—was turned into a Revier at an unspecified date.

Normally there was a sort of infirmary for external care (Äussere Ambulanz) that treated—with a limited number of ointments—wounds of all types. There was also the Innere Ambulanz, where a decision was made either for a patient’s hospitalization, or a limited period of rest (Schonung), or simply a return trip right back to the Kommando. One way or another, only a fever of at least 39 degrees Celsius was considered as truly ill; for a long time an initial selection was made on this basis in a barracks at the very end of a hall in the tunnel—apparently Hall 36.

Information on Dora’s Revier personnel is often uncertain, but this is not particular to Dora. The SS doctor, the Lagerarzt, was at first a certain Heinrich Plaza, described by Jean Michel as “a tall guy, with the mug of a brute”; he was dangerous when drunk and insulted the prisoners.1 He came from Buchenwald where he was in charge of pathology and entirely incompetent. After Dora, he passed through Struthof before being appointed to Ohrdruf. He was replaced at the beginning of 1944 by Dr. Karl Kahr, who remained there until December and who will be mentioned in a later chapter.

It is difficult to know if the Kapo—in the initial months—was Ernst Schneider, a builder, or Karl Schweitzer, a stove fitter. They were both Reds and filled in as surgeons as the case required.2 The arrival of Fritz Pröll in April 1944 brought with it major improvements. Little by little and in an erratic manner the prisoners became part of the Revier personnel. The main figure was a Dutch doctor, Dr. Groeneveld, who arrived in Dora with the first convoy of August 28, 1943, remaining there until the evacuation in April 1945 with the last convoy. The first French “doctor” (in fact a dental surgeon) seems to have been Dr. Jacques Desprez, who arrived in September with the other “20,000”s. He cropped up again in Harzungen. Then came Dr. Maurice Lemière, who maintained his duties up until April 1945. Among the dentists were René Laval, Georges Croizat (dental technician, who passed through Peenemünde), and Jean Michel—recruited thanks to Jacques Desprez—who looked after the files as he had no medical training.3 It was during the first months of 1944 that the French team grew significantly, as will be seen, with the presence of Louis Girard, René Morel, and Marcel Petit among others. The Czechs, equally present, were principally represented by a dentist, Otto Cimek, and by a surgeon, Jan Cespiva.

GROENEVELD, THE DUTCH DOCTOR. Born in 1907, H. L. (known as Hessel) Groeneveld set up his medical practice in Nijmegen in 1935. He belonged to the Mennonite Church, an important church in the Netherlands, where it was created in the sixteenth century. Groeneveld joined the Resistance, was arrested, and escaped. He tried to reach the Pyrenees but was once again arrested during a roundup in the Paris métro in November 1942. Imprisoned for many months in Paris, he was then transferred to Compiègne in the spring of 1943 and deported in June to Buchenwald, where he was assigned the identity number 14340. Some Dutch friends managed to place him as a nurse in the Revier.

On August 28, 1943, he was in the first convoy of 107 prisoners sent from Buchenwald to Dora; in his memoirs, Groeneveld noted that only 7 of them were left in 1945. Initially he worked in the tunnel, then became a nurse again once the Revier was set up. He finally managed to have himself recognized as a doctor. After him, many prisoner-doctors arrived—French and Czech in particular. But Groeneveld’s authority remained. Those attesting to his competence and kindness are numerous, French prisoners like Sadron foremost among them.

Chapter 19 will deal with the role he played in the evacuation and how he got back home.

GETTING INTO THE REVIER, AND GETTING OUT. Quite naturally, prisoners who fell ill sought medical help and thus turned to the Revier. But it was difficult to get into the Revier, as many prisoners have explained. For a number of weeks it was necessary to first go through the tunnel infirmary. The following accounts were made by Fliecx, followed by Butet.

“I went to the [tunnel] infirmary. It was a horrible barrack built at that time in the large gallery that led to the Blocks. [. . .] We waited outside. It wasn’t very well lit and we were squeezed together in the shadows. Off and on, the door would open, throwing light upon the strange combination of the wounded, the sick, the dying and those who wangled their way in. On the other side of the barrack was the morgue, a pompous title for the canvas curtain that didn’t even hide the lifeless, dirty bodies that piled up behind it. Sometimes men that still had some life left in them—but not enough life to bother with—were brought in there.”4

“I was coughing constantly [. . .] I decided to go to the doctor’s office by reporting sick. The infirmary, the Revier, had just been set up in a barrack in the camp. For those of us from the Tunnel, it was simply out of the question to go there alone. You first had to check in at the Tunnel infirmary, a small barrack set up at the far end of the gallery. Lording over the operation was a Russian prisoner, with several assistants. His only equipment was a medical thermometer and a few papers. We started lining up in front of the door; no doubt to set the mood, several dead bodies were piled up at the side.

“When it was my turn, he handed me the thermometer, without a word. I took my temperature under the arm—it was almost 39 degrees Celsius. He wrote my number down on a piece of paper, stamped it and motioned for me to wait outside. [. . .] We were thirty or so to leave the Tunnel under the supervision of a Kapo, feet treading through mud, the French prisoners rubbing one another’s backs to get warm. The examination was quickly done by a prisoner doctor, he listened with his stethoscope, gave me two aspirin and the secretary wrote out four days of Schonung on my paper.

“I don’t know if it was the aspirin or the prospect of not working for four days that gave me back some hope, but I returned to my Schlafstollen (dormitory) saying to myself that ‘they’ may get my fat, but surely not my skin and bones, and that I was going to fight ‘to the death’ to live.”5

Fliecx managed sometime later, in the first weeks of 1944, to get himself hospitalized in a Revier that was transformed inside: “The Revier is a barrack at the top of the camp. You miserably flounder about in a horrible quagmire to get there. Once there, you wait in front of the door no matter what the weather, those with forty-degree fevers mixed in with the others. Obviously, it’s always the strongest who push the others out of the way and slip in as soon as the door opens. The sick and disabled remain several hours shivering in the wind and snow. Some collapse, exhausted, to the ground. [. . .]

“Medical care? Oh excellent if you’re fortunate enough during the visit to be sent to the Revier, all the prisoners’ dream. It was my good fortune that the doctor—a German political prisoner—after giving a rough feel at the two pigeon eggs that were developing under my arm, sent me there. Before entering the room, there was a delightful moment: I was undressed and bathed in a real bathtub with hot water.

“In room eight, it was a French doctor who gave the orders; the nurse was Russian. Here in the Revier the change was one-hundred percent from the rest of the camp. Everything was clean, everyone had a wooden bed, a sheet, a pillow and a warm blanket. There were twenty of us. Lots of Italians. [. . .] We didn’t know what to do with all the food there. [. . .] In the mornings, I woke up naturally for the first time in ages. Everything was calm. [. . .] There we were well taken care of, pampered even, and the next day you’d be thrown back, with the same indifference, into the hellish life of the KL. . . .”6

Dutillieux had the same type of experience: “During the days that followed [the disinfecting campaign of February 1944], I no longer itched from lice, but I started to cough. The fever had hit me. [. . .] Roland told me the trick: ‘Just before roll call, smoke a cigarette dipped in machine oil. When the Kapo gets you to step out of the line up, you’ll be at forty. When you get to the Revier and the nurse takes your temperature, you’ll still be over thirty-eight.’ [. . .] Everything went as planned. [. . .] After having me swallow an aspirin and gargle with permanganate, they led me to my bed. It was the top bunk of a bed with only two levels. [. . .] With sheets! [. . .] My closest neighbors were three feet away on each side, I was out in the middle! Compared to the Block, this Revier was very comfortable, sumptuous. [. . .] I spent eight days there, with absolutely nothing at all to do, a total rest. [. . .] I was unable to swallow anything other than milk, my mouth was so full of canker sores. [. . .] For eight days I spat blood. [. . .] My pneumonia cured up without any medication—except for the aspirin and the mouth wash the day I entered the Revier. [. . .]

“The remedy for bringing down a fever and curing pneumonia or pleurisy was simple: dip a blanket in a bucket of cold water, wring it out well, fold it into fours the way you would a sheet, and wrap it around the sick person’s bare chest. [. . .] It was left there for about a quarter of an hour, the time it took the blanket to heat up a bit. After eight days of this treatment, the result was surefire: if the patient wasn’t already dead, he could go into convalescence. In any case, the fever would have fallen.”7

Rieg was saved by the same type of treatment: “From 7 February to 13 March, 1944: in the Revier with a bronchial pneumonia. It seems I moaned for eight days with a fever and nothing to eat. A Czech male nurse made me chipped-ice packs to put around the chest, the only remedy at his disposal.”8

Minor surgical operations were also carried out, such as the one meant to rid Fliecx of his abscesses: “That morning, they operated on my abscesses. Laid out on the operating table, I watched the doctor preparing his scalpel. It was dull and it tore at me; I heard the flesh rip under the blade; on reflex I sat bolt upright. The male nurse laid me back down with a violent slap in the face. I sweat off my last fat molecules. Next, my arm was wrapped in paper bandages which were to remain on for approximately twenty-four hours. It didn’t matter, I was very relieved. It was terrible how abscesses could wear you down.”9

Quite obviously, the prisoner personnel of the Revier—with the support of the SS doctor—did what it could with the scant means at its disposal to help the small number of sick who were authorized to receive medical care for a limited time. There were those who succumbed, and who justified the opinion—common in the camp—that the Revier was the antechamber to the crematorium. However, there were those whose state of health apparently improved, and who were allowed a rest, in the Schonung.

THE SCHONUNG. The Schonung was initially a short rest period of a few days, access to which depended on obtaining a paper stamped by a doctor from the Revier. The recipient was authorized to return to his block and do nothing, as Butet did for four days in his sleeping quarters in the tunnel. Possibly the SS considered one day that all these prisoners lazing about seemed disorderly, and so it was decided to regroup them into a special block of the camp.

As André Rogerie has noted: “Monday came and this time Buchet went up to the Revier with me. It was his turn to be examined; we both had pneumonia. This time, we preciously guarded the note which I was so lacking and we spent the day in Schonung. But, at that point a change occurred: those in Schonung didn’t go back to sleep in the Tunnel. They stayed where they were and went to roll call. Oh! These deadly evening roll calls, on your feet for hours, we standing in the snow and shaking with a severe fever. We no longer ate. We had to drink, drink. [. . .] During the day, we had to sit on stools without backrests. [. . .] In the evening, the stools were taken away and straw mattresses were laid on the floor. And, as if that weren’t enough, I contracted dysentery.

“The 27 January, I received my first care package. [. . .] The sugar brought my appetite back and I ate everything that day. [. . .] The day after, I found a little box of pills in my pocket, [. . .] in fact it was for dysentery—Stovarsol—that had been given to me in Compiègne. [. . .] Because the Schonung was full, the doctor decided to send me back to work.”10

Fliecx and Dutillieux went to the Schonung after going through the Revier.

“Done with the hospital! I was sent to the Schonung. It was no longer in small barracks, but now in a Block of the new camp. We slept on straw right on the floorboards. [. . .] We stayed sitting on stools all day long, so much so that our backsides hurt; but, all the same, we were happy not to be working. [. . .] The guard was a Czech, Victor, who yelled stupidly morning and night. [. . .] I stayed in the Schonung for a while. Then, I went back down into the Tunnel.”11

“Leaving the Revier meant therefore either the crematorium or the Schonung, the rest or convalescence building. [. . .] To the left of the entrance was a large room without any furniture. Hundreds of ‘convalescents’ were packed in. At night, all the bodies laid out covered the entire floor. [. . .] In the morning, the corpses were taken out and thrown into a heap in front of the building, where a special Kommando, the Totenträger, came to pick them up. [. . .] As for the large room to the right of the entrance, I never went in. I only know that it is much worse than the room in which I find myself resting. It was reserved exclusively for those with diarrhea. [. . .]

“Several times a week, a camp doctor, a prisoner, came to the Schonung building and pointed out, after a quick examination, those who were well enough to return to work. I was lucky enough to be seen by a French doctor. [. . .] The doc asked me if I wanted an extra eight days in Schonung. [. . .] But, eight days in that hell was enough for me. [. . .] So, I went back to the Tunnel.”12

Fliecx’s last visit to the Schonung was to the dysenteric room: “I was transported on a stretcher from the Tunnel to the camp. [. . .] When I got up there, I was hoping they’d send me to the hospital. But no, they judged me still to be in too good shape; you had to be in the throes of death to get in now. I was again sent off to the Schonung, to the room reserved for those with dysentery. [. . .] They had me take my clothes off, and sent me into the ‘Scheisserei’ room. The first thing that hit me was a foul stench, then I moved a few steps forward. On all sides, lying on disgusting straw mattresses, were skeletons, their dirty gray skin hanging from them.

“The next day, I was really not well. [. . .] Then I too collapsed into the torpor that seemed to wipe out all the sick there. [. . .] How many days did I remain like that in the Schonung? I couldn’t tell anymore—between three and eight days, I suppose. [. . .] I received another package. Maybe that was what saved me, because I was at the end of my tether. I managed to eat a pot of quince jam, one of honey, and drink a bottle of syrup.”13

THE “TRANSPORTS.” At the beginning of 1944 a significant number of prisoners—in the Revier, Schonung, tunnel, and in the camp—were unable to work. Many of the prisoners had already died; but others still, sometimes referred to as Muselmänner, were perhaps going to take awhile to die. Space was lacking, sleeping quarters in the tunnels were full, and the camp was still very rudimentary. And new prisoners were expected to arrive from Buchenwald at the moment when the factory in the tunnel would finally be able to produce the V2s. Those of no use in Dora had to be gotten rid of.

Therefore it was decided in January 1944 to organize a “transport” to the Maïdanek camp, close to Lublin, within the Polish General Government. The affair was planned with the greatest secrecy, and the destination remained unknown. Officially, it was to be to a rest camp. Later it was referred to, no doubt sarcastically, as a Himmelkommando, a heaven Kommando.

There were apparently no survivors from that transport, for which the date varies from one source to another, the most likely being January 6. According to Jean Michel, it was Dr. Jacques Desprez who knew of the destination.14 Michel also quotes the account given by Pierre Rozan, who met a completely drunk SS man who had taken part in the transport. He complained of the work he was made to do: “I was disgusted: forced to do a job that made me sick to my stomach. Might as well have me work in the latrines, wallow in the shit. I had to deal with the sick who could no longer get out of the railway cars. They didn’t want to stand up. I had to crush their larynxes by stomping on them with my boots to finish them off.”15

It was necessary for this transport, as for so many others, to have everyone accounted for after a roll call in order to proclaim, “Die Rechnung stimmt!” The transport comprised one thousand sick men. Michel told how Raymond de Miri-bel avoided the departure in the nick of time by speaking in his approximate German to an SS officer, who he knew bore the same name.16

There is more known about the second transport, also made up of one thousand men, leaving Dora on February 6 and arriving in Maïdanek on February 9. André Rogerie provided a highly detailed account of the journey and period spent at the Maïdanek camp from February 9 to April 15. When he left the camp to go to Auschwitz, he observed: “Of the 250 Frenchmen who left Dora with me, there were only eight left and it wasn’t over yet.” According to his testimony, the Polish, in general, fared much better.17

The third transport left Dora on March 26 and arrived at Bergen-Belsen on March 27. Fliecx’s is the most detailed account of the trip and the first weeks at Bergen-Belsen. Like a few other French, he remained on at Bergen-Belsen and survived. He ended up being the orderly of the Lagerältester. He relates: “In the office I consulted the camp registers. Often I took the first one, the transport from Dora. All you could see were gallows crosses in red pencil! Pages practically covered in them. On 27 March 1945, the anniversary of our arrival in Belsen, I counted the survivors: fifty-two out of a thousand! And of the 600 French, only seventeen remained. Three percent. The last handful, the toughest.”18

To explain these deaths, over a year, it must of course be taken into account—but to what degree?—the circumstances particular to Bergen-Belsen. It must also be taken into account the (rare) cases of those who, considered cured, were sent back in August 1944 to Buchenwald and from there to Dora. This was the case of Didier Bourget and Roger Tricoire. It was also the case of the Slovenian Matija Zadravec. The first convoy took those involved by surprise. Afterward, some of the sick became suspicious. Rieg had only barely recovered than he got out of the Revier.19 Dutillieux didn’t linger in the Schonung. Others let themselves be dragged along through lassitude. As Rogerie has revealed: “I coughed off and on along with violent coughing fits. But, tonight there was some excitement in the Tunnel. A ‘transport’ was being prepared. Everyone unable to work had to leave the premises that night: the Revier, the Schonung, the sick, everyone had to take the train the very next day—Sunday—to an unknown destination—to a better camp, so it seemed. In fact, it was an extermination transport, but I wasn’t aware of that yet and it was—my God—with great satisfaction that I saw my name noted down so I could also take part in this expedition.”20 Bronchart pointed out that he wasn’t able to convince Étienne Bordeaux Montrieux not to go.21

Fliecx, like so many others, was in no position to react: “And then one day we were given striped outfits and we all left the Schonung. [. . .] We were around a thousand [in a barrack]. [. . .] Then, they led us out. In a blurry dream, I went down the camp pathway. What a strange marching parade we must have made! The camp head and the whole gang of Greens surrounding him hung to the sides: ‘Nach Sanatorium!’ . . . they screamed as we passed by. [. . .] Below, on the tracks, the cars were open. I was heaved in. Instinctively, I dragged myself into a corner and waited, passively, for what would happen next.”22

A strange thing happened to Simonin: “One night, I was taken out of the Block by a green Kapo (Kurt), then led to an administrative building where a Schreiber asked me if I had been sick. When I said I had not been, he opened a door to the outside for me and ordered me to quickly return to the Block. I later learned that it was in order to fill up a transport to Lublin.”23 Another victim would have to be found.

Another story is told by Joseph Jazbinsek, whose young brother François died in the second convoy to Maïdanek. Himself laid up sick in the Revier, he was forcibly marched to the tunnel by his Kapo Willy, who came to get him with two other prisoners. The next day Willy took him back to the Revier, which had meanwhile been largely emptied of its occupants, who had left in the transport for Bergen-Belsen. It was in this way that he survived.

THE TUNNEL’S VICTIMS. Not all the deaths in Dora occurred in the Revier or the Schonung. There were all those who, in the tunnel, died suddenly because they simply could not hold out any longer.

I shall quote just one example: “Among our fellow prisoners arrested the same time we were, was Marius Reimann, from Albert in the Somme, and his son Claude. Upon arrival in Buchenwald, Marius was given the number 39568, Claude number 39569, and myself number 39570. We arrived at Dora together on 11 February 1944. One morning, Claude found his father dead beside him. That day, Marius was one of the ‘deaths in the Tunnel.’ He appears on the list dated 28 February 1944.” Rogerie quotes another: “Then Buchet got up a last time and all of a sudden collapsed to the ground. He was dead. His body was immediately thrown onto the heap of the day’s dead. There were easily fifteen there, piled up any old way.”24

Corpses were placed in heaps, particularly in front of each of the dormitories, as noted by Butet and Mialet.

“I was picked out by the Kapo of the Schlafstollen who hit me, but especially conscripted me to take out the night’s dead. And indeed, when the ‘reveille sounded,’ ten to fifteen prisoners, or more, did not get up and remained huddled on their straw mattresses. They died in their sleep. [. . .] They had to be taken out and carried to the Tunnel entrance. [. . .] I didn’t much appreciate this duty, and the next day I went back to loading rocks into the carriages.”25

“Only seven corpses [at the door of the block], stiffs we called them. The bodies are bare-footed, with shaved heads. We see the enormous nails, the filthy toes, and the emaciated faces. All the dead looked alike in their ugliness and extreme thinness.”26

These deaths posed an administrative problem, as pointed out both by the Czech Litomisky, at the block level in the tunnel, and the Dutchman Van Dijk, at the level of a large Kommando.

As Litomisky explains, “Every morning and every evening, the Block personnel brought the dead bodies to the entrance, where the Schreiber established a list of the dead prisoners’ identity numbers and passed them along to the Arbeitsstatistik. The bodies were then put in a special enclosure in the Tunnel, where they were stored for several days. In the end, wagons were brought around to pick them up and take them out of the Tunnel. Meanwhile, it often happened that prisoners would get into the enclosure to exchange their clothes for whatever they found that was better on the dead bodies. But these clothes bore the identity numbers of the dead. After a while, the SS no longer knew who was dead and who was alive. They relied on the Arbeitsstatistik, whose information was also perfectly inaccurate. For this reason, it was one day decided that the identity number would be written on the foreheads of the cadavers with a special marker.

“One evening, an incredibly filthy and dusty Italian crept into the Block, looking for some food. After a while, the Block personnel noticed he had his matriculation number written on his forehead. He was one of the morning’s ‘dead.’ We were all dumbfounded. The Italian, meanwhile, as filthy and dusty as ever, couldn’t understand why we were all laughing so much at the very sight of him. He kept repeating, ‘Pane, pane!’ He was actually very fortunate to have landed in Block 4. Most of the Blockältester would have clubbed the poor Italian to death, in order to bring him into line with the registers.”27

Van Dijk’s recount is no less evocative of the problems confronted: “As [my Kommando’s] messenger, one of the most disagreeable duties fell to me: I became an accountant of the dead. After the roll call, I went with Wladi and two on duty helpers—a Ukrainian by the name of Joseph and a Tartar with an unpronounceable name—to the Blocks in search of those who did not show up for the roll call. It wasn’t difficult to find them. Most often, they were found dead or dying in the ‘clutches’ (the name given to the dormitories), or outside on the excrement-spattered ground. I would write down ‘verstorben’ behind the corresponding number on the list and I copied it onto the forehead or the chest of the dead man with the help of an aniline pencil which I wet with my saliva.

“It happened that we would arrive too late, and we’d find the dead, or even the dying, already unclothed. It was therefore impossible to identify the body. I had my own method: I just used one of the numbers remaining on my list and that we couldn’t find. For the prisoner who, through exhaustion, was no longer able to get up, I wrote that number on his arm. That way he’d be identifiable once dead. I then wrote down the corresponding number under the list ‘krank.’ Most often, the sick man was already dead by the next roll call but he was still listed as part of the Kommando for his food ration. It happened that there remained still other missing numbers. So, we went in search of them in other Kommandos to complete my lists.

“While Wladi and I continued our search in the ‘clutches,’ the two helpers dealt with the dead that we had found. That is to say that they took off the still usable clothes, and sometimes extracted the crowns in gold or silver from the mouths of the corpses. After this preparation, they put a sliding knot round the two legs, or the neck, and dragged the corpse behind them all the way to the heap in the main tunnel.”28

Bronchart, Fliecx, and Auchabie each in their own way recall the next step in the operation.

“From the Blocks [. . .] the dead were brought to hall 36, which we called the boulevard of the flat-out. So were the latrines. There, two Kommandos dealt with the evacuation. For the dead, it was two bodies to a wheelbarrow. By pulling them, dragging them by the feet, they were piled in a heap at the Tunnel exit. [. . .] The latrines were evacuated by hand. We didn’t pass through this hall lightheartedly. Often we were forced to by the SS.”29

“The dead were more and more numerous. Every morning they were piled up at the exit to the Blocks. From there, they were transported to hall 36, where the undertakers loaded them onto iron wheelbarrows, two by two, dragging their feet on the ground, their heads banging against each other on the wheel. The undertakers received quite a few perks, so they could allow themselves the sport of racing the wheelbarrows to see who would arrive first to the Tunnel door, with hearty laughs when the wheelbarrow bumped into something and tipped over. These macabre chariot races had long since ceased to upset anyone.”30

“The dead from underground were transported to gallery 36, where a carriage transported them out of doors. In gallery 36, it was not unusual to see a prisoner, no doubt having fainted, make every last effort to get out from under the heap of corpses. It was said, on the other hand, that the Russians hid themselves there to avoid work. [. . .] To survive, underground, when a corpse was found, his identity number was unsewn, and then resewn on top of our own with a very thin electrical wire, which allowed us to get his soup and his ration of bread for as long as his corpse remained undiscovered.”31

INCINERATION AT BUCHENWALD. There are few testimonies on the transport of the corpses to Buchenwald. It was Fliecx who described what happened: “From the window of the Schonung, the small carriages could be seen coming from down below, at the Tunnel exit, loaded with the dead. [. . .] Not far from us, the convoy stopped and the corpses were transported into a small shed close to the Revier. There they were kept up to three days until the truck came to take them to Buchenwald. There were about a hundred each time. . . .” (These were not only the dead from the tunnel, but those from the Revier and the Schonung.)32

He adds: “One time the driver of the truck had quite an experience. In a sharp curve in Nordhausen, one of the slatted sides broke off and all the bodies were thrown onto the road. Public commotion. Immediately a Kommando of prisoners was sent to fix up the incident.”33

Until the end of March 1944 it was at the Buchenwald crematorium that the bodies regularly arriving from Dora were incinerated, which gave it its terrible reputation. As will be shown in chapter 10, a “countryside crematorium” was then set up in the camp. Dora’s ultimate crematorium, which has been conserved, was much later.

THE DEATH TOLL. Survivor accounts, whether published or not, often include number estimates of losses suffered up to 1945, at least as regards the French. This is true of Bronchart’s book.34 Such information is generally not acceptable. It is based, for example, on the census of the French carried out at Bergen-Belsen in April 1945 before the repatriation, whereas the evacuations had in fact led many French off in other directions. Because of various circumstances, the author did not actually get back from Mecklenburg until the end of May, without any particular difficulty; he was therefore absent at Bergen-Belsen. Rigorous work—starting with the convoys from Compiègne—such as that carried out by Paul Le Goupil, will ultimately provide a clearer picture.

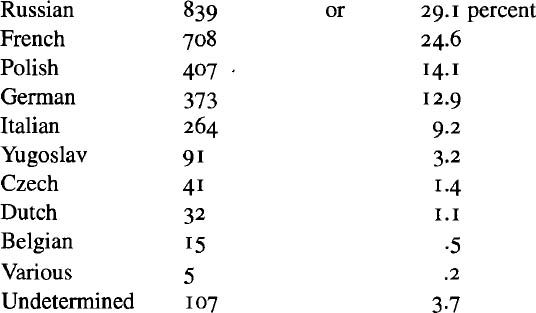

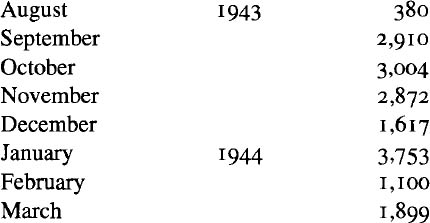

Concerning the first months of Dora there exists no uncertainty. The number of prisoners incinerated month by month at Buchenwald is known. A total of 2,882 dead can be broken down as follows:

A breakdown on the basis of nationality is also available:

This breakdown corresponds overall to arrivals in Dora. The “Russians” were above all Ukrainians, evacuated from camps in the Ukraine once the German troops had retreated in the second half of 1943. The convoys of French that left Compiègne in the second half of 1943 were directed toward Buchenwald. The Italian capitulation in September 1943 was followed by Italian soldiers being sent to Germany as prisoners of war after they stopped fighting on the German side; some of them were sent to Dora. The Yugoslavs who had been political prisoners in Italy were sent to German camps. The Poles and the Czechs came to Dora via other camps, especially Auschwitz it would seem. The high number of German deaths is surprising, as they essentially occupied the positions of Kapo, Blockältester, Lagerschutz, and so on.

It is known month by month the number of prisoners from Dora incinerated at Buchenwald. It is also known that one thousand prisoners were shipped off from Dora in transports for each of the months of January, February, and March 1944. On the other hand, the total figures are available of all those present in Dora at the beginning of each month from October 1943 to April 1944. It is possible to derive, from this information, the number of prisoners who arrived in Dora between the end of August 1943 and the beginning of April 1944.

There were some 17,535 prisoners. As the number of prisoners at the beginning of April was 11,653, the number of prisoners dead was 5,882: 2,882 incinerated and 3,000 taken away in transports. In total the number of dead represents a third of all those who arrived at the camp in a period of seven months. It is true that at the beginning of April there were still some survivors of the three transports to Maïdanek and to Bergen-Belsen. But the majority of them would more or less not have long to live.

The total number of prisoners at the beginning of each month grew as follows:

1 September 1943 |

380 |

1 October 1943 |

3,290 |

1 November 1943 |

6,276 |

1 December 1943 |

8,976 |

1 January 1944 |

9,923 |

1 February 1944 |

11,957 |

1 March 1944 |

11,521 |

1 April 1944 |

11,653 |

Arrivals, for each month, were as follows:

In spite of their large numbers, the prisoners who arrived during the first quarter merely allowed the level to remain at between 11,000 and 12,000 prisoners.

LESSONS TO BE DRAWN FROM THE “GREFFIER LIST.” An attempt can be made to describe with greater precision what actually happened by using the data provided in a precious document with regard to the French alone, and which is known by the name of the “Greffier List,” from the name of the man who brought it back to France in 1945.35

It is made up—in alphabetical order—of the names and surnames of the French prisoners who died at Dora, including identity numbers, dates of birth, and dates of death. This document, like all documents of this type, is not perfect because it contains numerous errors, particularly regarding names. But various cross-checking has shown that, essentially, it is a reliable source. For the period up to the end of March 1944, the number of identified dead was 685, corresponding roughly to the number of French indicated above in the breakdown by nationality, which was 708.

On the basis of the alphabetical Greffier List, it was possible to draw up two other lists, one with a classification of identity numbers and the other with a classification of time of death, providing information of particular interest.36

Starting from the chronological list of deaths, it is indeed possible to establish a ten-day chart that indicates the great number of deaths between the beginning of December 1943 and the end of March 1944. The highest number of deaths were initially registered in the last ten days of December and the first ten days of January, and then during the three ten-day periods of March, following the great disinfecting campaign. The death rate fell abruptly in April. It is difficult to draw a conclusion because of the three transports in January, February, and March: many of the sick evacuated in March, for example, would without a doubt have been dead by April had they remained in Dora. Whatever the case may be, the slaughter, with regard to Dora, then drew to a close. The fact that it then started up again, in Ellrich and the Boelcke Kaserne, is another aspect of a complex historical whole.

A STEEP DEATH RATE. Using the Greffier List, it is possible to plunge still further into what can be known about the first months of Dora by cross-referencing the information on the times of death with that of the dates of arrival inferred from the identity numbers. It can be assumed then that the prisoners who had similar identity numbers—the “21,000”s for example—all arrived at Dora at the same time, that is, after being released from quarantine at Buchenwald. However, it is known that some of the French remained in Buchenwald for a more or less long while before being sent to Dora. But examination of the survivor list shows that the number of such cases was limited during the time frame under consideration.

Statistics have been established on the dates of death for the French who had identity numbers up to “32,000,” in other words, those who arrived at Dora before the beginning of December 1943. It has been observed that 554 of them were dead before April 1, 1944, and 141 in the course of the entire time period that followed until the evacuation in April 1945. Only a few weeks were required each time after the arrival of a transport for massive numbers of deaths to be registered. Several accounts bear witness to this situation.

Mialet noted the first death among the French prisoners as André Commandeur (21684), on October 27, 1943, age nineteen. In fact, it was Maurice Cauchois (22815), on October 23, age thirty-eight. “It was the first death. We prayed for him. A Protestant minister who was part of the Kommando, led prayers for believers, and offered thoughts upon which to meditate for free-thinkers. Everyone discovered their true selves. The cropped heads bowed. The little French guy went up to paradise, escorted by the ardent pleas of these men who, all now, continued to waste away and of whom a good many, as Christmas approached would, like him, be dead.

“A little Russian guy watched the scene. At the end of the prolonged silence, he touched my arm and asked: ‘Was ist das?’ I explained as best I could. The little deportee had a smile of understanding and perhaps of pity; with his left hand, he made the sign of the cross. The deaths that followed Commandeur’s were not favored with these pious words to accompany them. They were just too numerous.”37

Bernard d’Astorg spoke of his father, Colonel d’Astorg, deported from Compiègne in one of the January convoys: “I was in the Tunnel with the AEG Kommando. At the end of March, I met a Frenchman whose name I’ve forgotten who informed me with urgency that my father was in the Revier, very sick. I was completely surprised and I somehow managed to get permission to go up immediately to the Revier. I remember that the sun was blazing and that crossing the roll call area to reach the Revier was for me a dream-like moment.

“When I arrived at the Revier, I was shown where to find my father. And indeed, there I found him lying on a straw mattress which he was sharing with another dying man. He was practically naked, had dysentery and pneumonia (or pleurisy), was very thin and already difficult to recognize. But, his morale was incredible. He told me how happy he was to see me in a somewhat healthy state, and told me to hold out because, he added, the landing wasn’t far off, ‘a few months.’ The Stubendienst put an end after a few minutes to this reunion and I went back to the Tunnel.

“I started out once again a few days later on this expedition to the Revier. I learned that my father had left on a transport to a rest camp. I later learned it was on the 29 March transport to Bergen-Belsen. He died on 4 April 1944. The landing occurred two months and two days later.”38

André Rogerie (31278) arrived at Dora on November 21, 1943, and gave the names of those closest to him: Paul Corbin de Mangou (31276) died on January 2, 1944, Marius Buchet (31283) died on January 25, Jean Bourgogne (31300) died on February 4. Rogerie himself left on February 5 with Maurice Estiot (31298) for Maïdanek, where Estiot in turn died. He remained the only one left from the initial group.39

Pierre Auchabie (30750) also arrived on November 21, 1943, at the same time as twenty-one other deportees from the Corrèze, Dordogne, and Haute-Vienne. He drew up a death toll: died on November 26, Henri Julien (30438); on December 11, André Lizeaux (30775); on December 12, André Eymard (31069); on December 15, Sylvain Combes (30471) and François Paucard (30690); on December 22, Émile Dupuy (30751); on January 18, Valentin Lemoine (30493); on February 4, Jean Blanchou (30665); on February 6, Pierre Maisonnial (30659); on February 22, Jean Lanemajou (30816); on March 8, Antoine Maisonnial (30603); and on March 26, Fernand Ratineaud (30704). Those leaving on a transport and not returning: Fernand Astor, Jean de La Guéronnière, Abel Lalba, Albert Lizeaux, Pierre Lizeaux, Antonin Mazeau, André Paucard, and Antoine Pouget, all from the “30,000”s. Alfred Maloubier (30673) died on February 6, 1945, at Ellrich.40 Pierre Auchabie was the only one to make it home, via Ellrich and the Boelcke Kaserne!

Rogerie and Auchabie, like many others, fell upon bad Kommandos. This was not the case for everyone; if so the only survivors would have been saved by a miracle, as they were. To some extent this was what some people upon their return thought had happened. Rassinier wrote in 1948 still, regarding convoys “20,000” and “21,000,” that only a dozen remained on June 1, 1944 out of the fifteen hundred who arrived in October.41 Which was, very fortunately, highly exaggerated.

It is altogether undeniable that in a few months tens of thousands of men, perhaps not deliberately but in any case knowingly, were killed at Dora. The impression is given that these deaths just simply didn’t matter. It was the price to pay. It is, under these circumstances, at once necessary and difficult to determine where responsibilities lay.

INDIVIDUAL CRIMES OR COLLECTIVE RESPONSIBILITY? When one looks closely at what happened at Dora during the first few months, it is striking to note the low number of individual acts directly causing a man’s death. There were certainly executions by hanging, but in small number, not more, so to speak, than in the everyday life of a normal concentration camp. Of the some seven hundred French dead, not one had been executed.

Some prisoners were savagely beaten after trying to escape from the outside work sites and died some days later. Such was the case of Paul Belin, who died on November 19, 1943,42 and André Legrand, who died on December 29.43 But if a trial for the murders of this period had taken place, it would have no doubt been very difficult to find and expose the guilty parties.

If so many prisoners died, it is due to a certain number of converging factors: the fact that they were forced to work beyond their limits; the fact that they were forced to live in inhumane conditions; the fact that they were not given medical attention. All of which has to do with collective responsibility. First it is necessary, for clarity’s sake, to examine the information known about the various groups having participated in the surveillance of the average prisoner and about their behavior.

THE GERMAN CIVILIANS. The prisoners’ work in the tunnel and on the outdoor work sites was supervised by German civilians, generally described as Meister. Relations with the engineers at this period were exceptional. Most of the people involved in setting the factory up were no doubt transferred from Peenemünde. The others for the most part came from the WIFO or subcontracted companies.

In the German organization of trades, the Meister (“master”) was a tradesman with a recognized qualification and in a position to employ apprentices. In Dora the term was debased: it applied—for any task—to the civilian who gave orders to members of a Kommando, passed along by the Kapos and Vorarbeiter.

The names of the Kommandos most of the time were not very revealing. There was certainly no hesitation about the name of the AEG Kommando, whose activity was well defined. The name WIFO, curiously enough, does not come up often; there existed, however, a Kommando of masons, the WIFO Maurer, about which Jean Mialet has retained an atrocious memory.44 The large Kommandos bore Sawatzki’s name: there existed at least three, Sawatzki I, II, and III, which were involved in the development of the tunnel45 without a noticeable direct link to the Oberingenieur concerned. It is possible that these designations were relevant only to the Arbeitsstatistik files.

The Meister left the disciplining to the Kapos and SS. They were moreover prohibited from personally punishing the prisoners. Some, like the characters involved in removing the gasoline tanks, were frankly hostile.46 The majority were indifferent. Some were discreetly benevolent, and Max Dutillieux felt it important to give a moving homage to “his old Meister [who] took a real risk” for him.47

PRISONERS WEARING ARMBANDS. It would be interesting to know how Buchenwald’s Arbeitsstatistik—under the control of the Reds—established the first lists of “transports” of German prisoners (Greens or Reds) to Dora. We are reduced to conjecture. Concerning the Greens, there is every reason to think that it was a very good occasion to get rid of both unsavory individuals and potential competitors for the good positions at Buchenwald. It was of course a very nasty trick to play on the French and Soviet deportees who had been sent to Dora to have them accompanied by German (or even Polish) criminals, who were destined to keep an eye on them as Kapos and Vorarbeiter.

A certain number of Greens, reduced to very subordinate positions at Buchenwald or even sent to the quarry, thus had the chance to vent their frustration—and did not deprive themselves. Their deep-seated xenophobia could then be played out on the Russians, the French, and the Italians without any holding back. Many of the Greens who wore armbands were somber brutes, shamelessly striking average prisoners in the Kommandos working on excavation, in the “stones,” machine transport, or frame building. Through their physical abuse, but no doubt just as much from their demented overseeing of the work, they were responsible for working many prisoners to death.

Dutillieux mentioned the Kapo Rudi Schmidt, who “was a piece of garbage,” and his acolyte, the Vorarbeiter nicknamed Jumbo. He clarified: “Seventeen Frenchmen were under the orders of Rudi at the end of October 1943. There were only three left alive by the end of winter.”48 Slightly later the situation altered: “Changing Kommandos, I changed Kapo; I left Rudi Schmidt for Willy Schmidt. I left a scum for a crook. Willy was bigger than Rudi, stronger, more intelligent and no doubt for that reason better considered by the organization.”49 It might have been that a certain selection was made in favor of certain Kommandos. Bronchart was able to have a cordial relationship with the Kapo of the AEG Kommando, who had been condemned only for counterfeiting.50

Concerning the Reds, it is immediately striking to note how few of them were sent to Dora. Quite plainly, the prisoner leaders at Buchenwald didn’t wish to risk the lives of their comrades in this altogether uncertain venture. Doubtless the commander of Buchenwald must have insisted on the appointment of two of their own for the positions of Lagerältester I and II of Dora. It ended up being a Bavarian mechanic, Georg Thomas, and a miner from Upper Silesia, Ludwig Sczymczak, both German communists, who were chosen. They arrived, so it would appear, already on August 28, 1943, along with the Kapo Lagerschutz Otto Runke.

Based on information quoted by Bornemann, next came Karl Schweitzer as Kapo of the Revier, Albert Kuntz as Lagertechniker and August Kroneberg as Kapo of the Zimmerei (carpenters), then Ludwig Leineweber (in October) as Kapo of the Arbeitsstatistik.51 A later chapter will focus on the role they would come to play.

Thomas and Sczymczak were, after the war, considered heroes for two reasons: they refused to serve as hangmen in February 1944, and they were killed in April 1945 with other communist leaders after weeks of imprisonment. Hermann Langbein noted that Thomas’s and later Sczymczak’s refusal had numerous witnesses. He added, without being more exact, that after a period in the bunker “they took up their camp functions again.” They appeared, in any case, to have been replaced as LÄ by a Green.52

The two Czechs who provided testimonies, Litomisky53 and Benès, were not in favor of Thomas, who apparently didn’t like the Czechs, perhaps because he was Bavarian. It appears that he had something against the “Czech Legion.”54 This was no doubt an allusion to the Czech Legion, made up of prisoners of war—from the Austrian army—who had fought in 1918 against the Bolsheviks while retreating eastward through Siberia. Benés, who was mixed up at that time in various intrigues between Kapos and other Prominente, Greens or Reds, provides a confused account, which brings out the great mediocrity of all these people.55 To want to pass onto some Häftlingsführung or other, as Rassinier did,56 the fundamental responsibility for the tragedy of the first months at Dora is to forget rather hastily the role of the SS and especially of those in charge of the manufacturing operation of the V2s—to which the camp was intrinsically linked.

THE ROLE OF THE SS. In all the prisoners’ accounts of the first months, the SS were in the background in the tunnel or with the outside Kommandos. In the tunnel they hunted down all those they considered layabouts from every nook—of which, at the time, there was no lack, in particular young Ukrainians. It was a reign of terror. The minimum punishment, for a long time codified in the regulations by Eicke, was “fünf und zwanzig,” twenty-five whacks on the backside. Outside the tunnel, the SS and their dogs were responsible for preventing escapes. As has been shown, the crackdown on those attempts could go almost to the extent of murder.

The SS’s direct responsibility was greater still, especially in the first weeks. First, they considered Dora to be a camp like the others, like all those they had seen up until then. It was thus out of the question to give up the outside roll call, even for those living completely inside the tunnel. As told by Bronchart:

“Every Sunday, for the Kommandos which were not at work, a roll call took place regardless of the weather. We exited the Tunnel and were made to stand to the left of the entrance, in the area where the sugar beet crops were. To get there in rows of five, we went arm in arm, so that the column wouldn’t break up, because sometimes the sick could no longer keep up. Watched over by the SS, with their dogs which intervened every time too large a gap swelled between two rows, we climbed the hill to reach the gathering site, the mud as thick as ever, sticking to and leaking into our miserable canvas boots. This march was real agony, and entailed fights amongst the prisoners for positioning; so much the worse for those who found themselves at the edges where the beatings rained down. . . .”57

Nor is there any question of considering that the prisoners were not, first and foremost, at the service of the SS. Maronneau explained: “Half of the convoy was led toward the Tunnel and put to work straight away in a drilling gallery. After a short night, we were taken outside to transport various parts meant for the construction of the future SS camp barracks. This system lasted around three weeks. Following the visit of high-ranking Nazi officials, it was decided to make two teams, one working outside constructing the camp, the other continuing the drilling and setting up of the Tunnel.”58

It seems, indeed, that the Buchenwald commander’s visit of inspection was needed to get things adjusted. According to Kammler’s instructions, absolute priority was given to the setting up of the tunnel factory and its access points.59 Everything concerning the camp was deferred. The outdoor roll calls disappeared. Sunday became an ordinary day. A general roll call took place later, in February, in the snow.

THE FACTORY CAMP. From November 1943 on, and for a period of several months, only the factory mattered: it had to get finished and get going. The camp was only a vast formless annex of which the essential element was the kitchen. It supplied the soup that the inhabitants of the tunnel came to eat at the door before withdrawing to the sleeping quarters and the work halls, with their dirt and their lice. When lice were discovered, a disinfection block was added to the kitchen. Because all available space was required for the factory, there was no possibility of building a crematorium for the corpses the factory “produced” with efficiency greater than that with which it produced the V2s. The months from November to March were the deadliest in Dora’s history.

All those in charge on the German side were involved in a frenetic race against time because they were all committed to Hitler and to supplying Germany with this famous rocket capable of changing the course of the war. Whether they really believed it or feigned—consciously or not—belief in it is of little consequence. The degree of collective illusion is surprising today, but that is a judgment after the fact. Many prisoners at that time were seriously worried when they discovered what they commonly referred to as the “torpedoes.”

The Germans in charge were the artillerymen as well as all the scholars and engineers working with them, since 1932, to perfect this new weapon—to which they had already devoted so much effort and money—perhaps to the detriment of other research. It was also the Armaments Ministry technocrats, who had not flinched in their support for the project since 1942 but were worried about the delays that were accumulating. It was, of course, the SS that sought obstinately to take control of the operation.

When examining the structure of competencies at the end of 1943, Albert Speer, then at the height of his influence, appears—as concerns the rockets—to have been in control of the situation. It was he who came to see the tunnel factory in December 1943 and who passed on to Kammler a message of satisfaction for the work accomplished. Perhaps this satisfaction was moreover excessive, because the reconversion of a fuel depot into a virtual aircraft-engineering factory was not such a feat in a country with Germany’s industrial tradition. But this country no longer had, at the end of 1943, the purely German labor force and the material means necessary to carry out such an undertaking in a normal time frame.

In the spring of 1943, before even the bombing of Peenemünde, resorting to the concentration camp labor force appeared to be the only way to confront the difficulties that had arisen. From that moment on everyone was aware of what was at stake and necessarily in agreement: Dornberger, Rudolph and von Braun, Speer, Degenkolb and Sawatzki, and Kammler. In the end, Neu had no choice but to follow.

The hell of Dora was a result of this mixture of personalities, all perfectly indifferent to the fate of these subhumans who were the prisoners. The author has found no criteria for placing individual responsibility on one person or another, or exonerating one or the other. It was the entire operation, as it had been conceived, that was nothing if not criminal.

To go further in placing liability, it would be necessary to have all the messages, instructions, minutes of meetings, and reports exchanged in all directions between those concerned. It would be necessary to have the dossier on the high-tension underground line running from Nordhausen to Kohnstein, or on the placing of the rails in tunnel B. It would be necessary to follow the process that culminated in the organization of the first transport to Maïdanek or to the general disinfecting campaign. There is nothing of this kind. There are not even any bits and pieces of dossiers. And it is better thus, as it avoids uncertain conclusions.

There were simply on one side thousands of victims, and on the other a group of leaders. That group of leaders was accountable, collectively, for the thousands of victims.