This section of maps is a key component of A History of the Dora Camp. It came together in parallel with the writing of the text and was worked out with the assistance of my son, Jean. It was then assembled by Anne Le Fur. The three of us had previously worked together on the Atlas des peuples d’Europe centrale (Atlas of the Peoples of Central Europe) along similar lines.

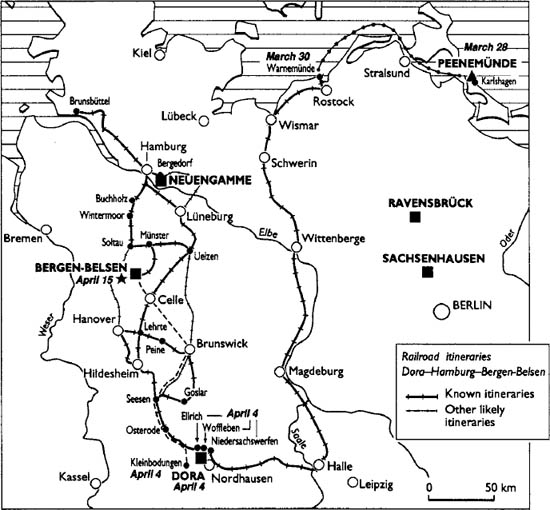

Because the maps and plans that comprise this section often correspond to a number of chapters, it seemed preferable to group them together at the end of the work following a logical order. The last maps thus correspond to the final phase of the evacuations. All these maps were designed to make up a homogeneous whole. The information was drawn to some extent from the important works already quoted in the text of the book, including Michael Neufeld’s, Manfred Bornemann’s, and Joachim Neander’s. Paul Le Goupil was of great assistance in reconstituting the itineraries of the evacuations described in chapter 20.

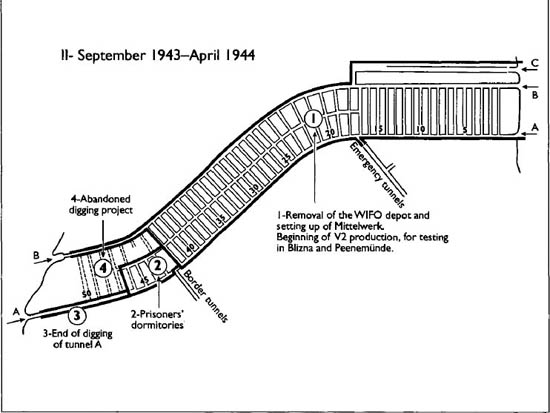

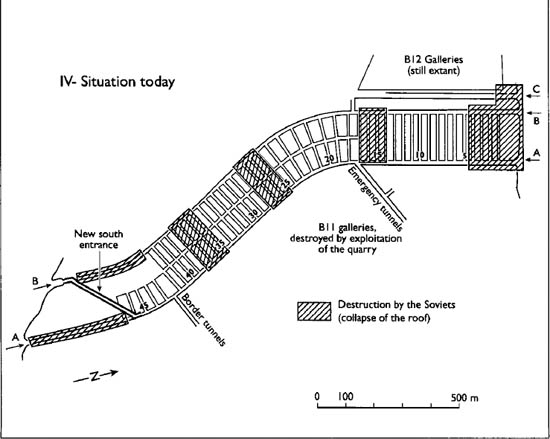

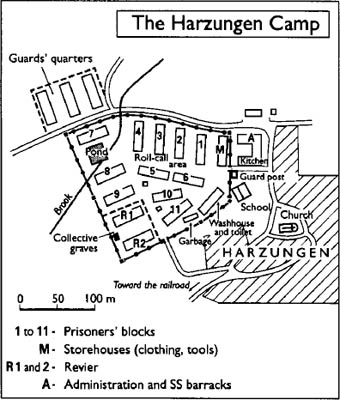

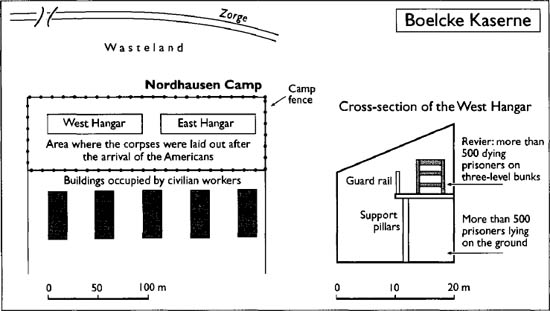

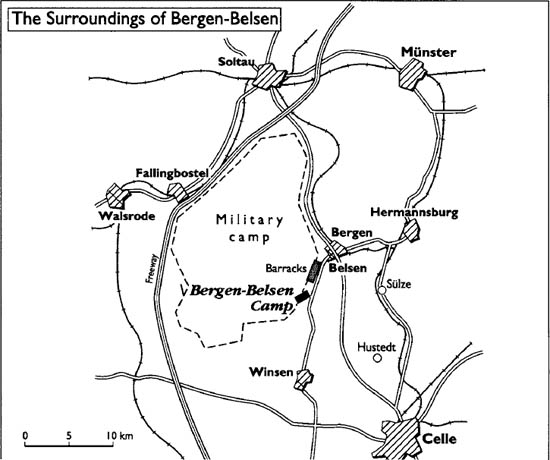

The maps’ origins vary. The Dora map is based upon a document from the time; every attempt has been made to render it as intelligible as possible. The Harzungen map was reconstituted by the Belgian prisoners’ association on the basis of a recently discovered aerial photograph; the preceding map, based upon memories, was in fact not very different. That of Ellrich is far more uncertain. Clément-Robert Nicola drew up the plan of the Boelcke Kaserne, and André Lobstein drew up the plan of the two blocks of the Dora Revier. The plan showing the block of the Dora camp corresponds to the barracks at the camp entrance. The blocks at the back of the camp had a more rudimentary plan, but there were always two Flügel, or wings. The plan of the Peenemünde base is reliable; that of the Bergen-Belsen camp is far less reliable.

Among the underground work sites of the Sonderstab Kammler the layout of B 3 is best known, on the basis of Bornemann’s reproductions. The plan shown corresponds to the projected layout and not to the situation at the time of the Allies’ arrival. The same goes for the plan of the Wizernes bunker. The interest of these two plans is to show the extent of the work sites undertaken from 1943 on—which led to so many victims.

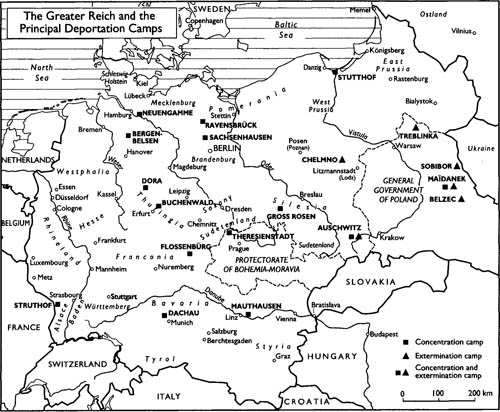

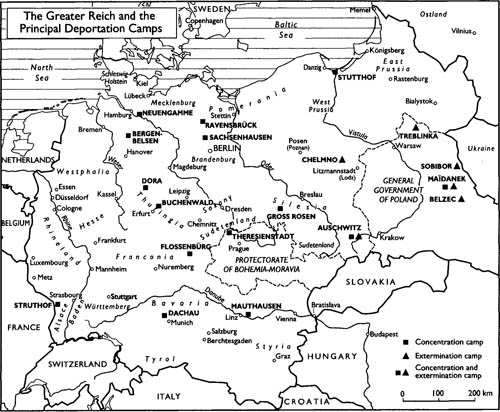

The limits of the Greater Reich were unilaterally established by the German government, in the west as well as in the east. They did not result from any treaty.

From Karlshagen to Ellrich

From Dora-Mittelbau to Bergen-Belsen

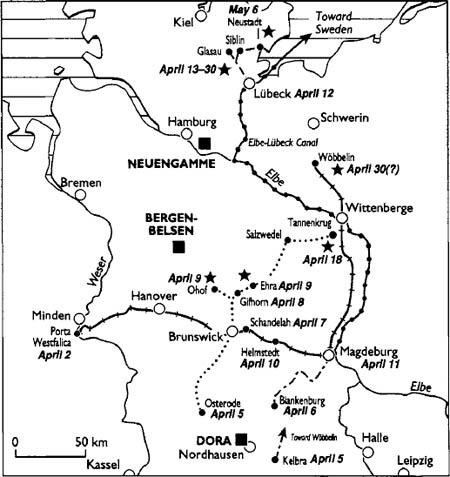

From Blankenburg, Osterode, and Porta Westfalica toward the north

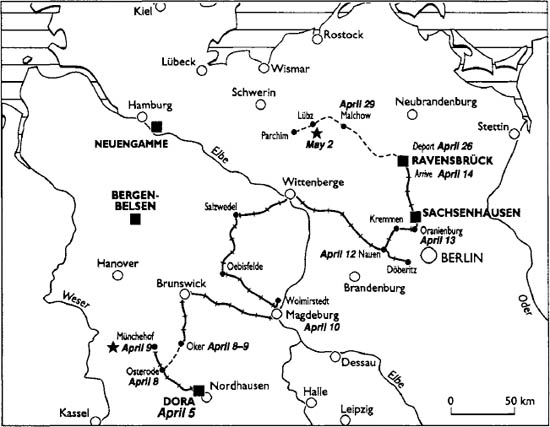

The last convoy from Dora to Ravensbrück and Parchim, arrival April 14

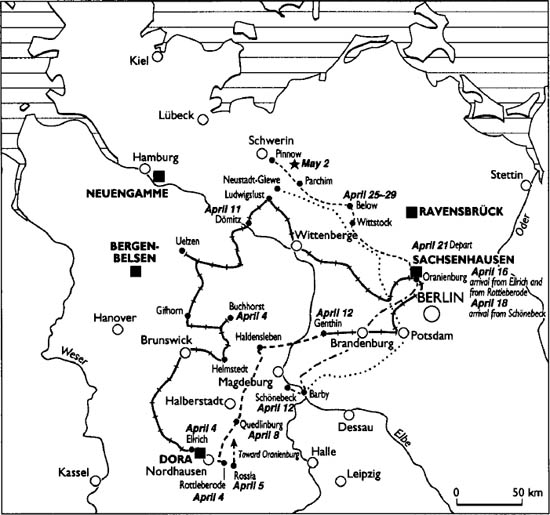

From Ellrich, Rottleberode, and Schönebeck to Sachsenhausen, and the evacuation of Sachsenhausen toward Schwerin

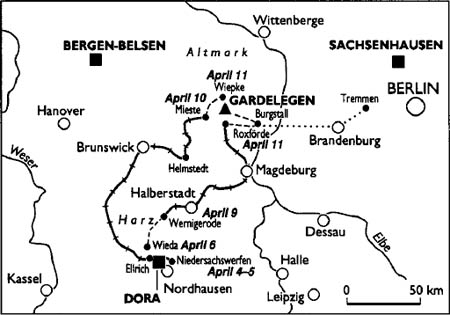

The Gardelegen tragedy

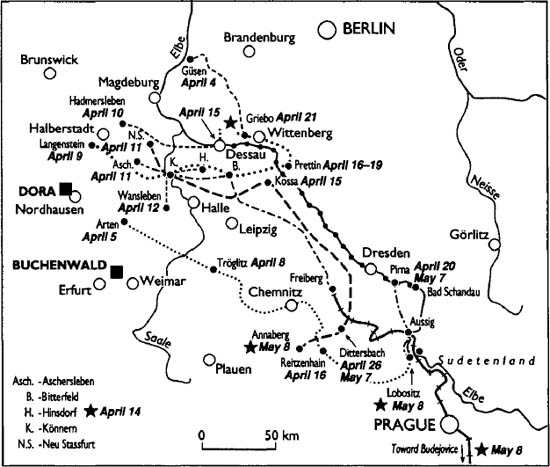

The itineraries from Arten, Langenstein, Neu Stassfurt, and neighboring Kommandos

Certain evacuations have been studied in depth by the various associations established by prisoners from the Kommandos concerned. This is the case for the “death marches” of the Langenstein and Neu Strassfurt Kommandos, dependent on Buchenwald, whose itinerary is known on a day-to-day basis. Only the principal stages are indicated. The crucial importance of the crossing of the Saale over the Könnern Bridge is noteworthy. The evacuation columns from Aschersleben and Wansleben crossed the river at that same point. The same map shows the itinerary of the evacuation of the Artern Kommando, dependent on Mittelbau.

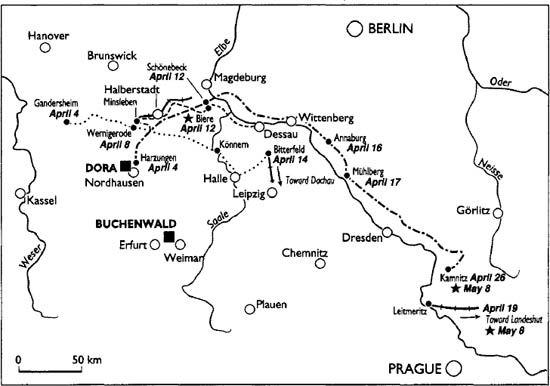

From the Mittelraum to the Sudetenland by various means

Among the most notable evacuations starting from Mittelraum, that of Gandersheim must be borne in mind: it began with a march all the way to Bitterfeld and was followed by an interminable trip by rail all the way to Dachau. The columns that left Harzungen on foot suffered various fates, as indicated on the map.

Between Mittelraum and the Sudetenland any number of other crisscrossing itineraries of evacuation could have been shown—ultimately rendering the map illegible.