IN THE LAST CHAPTER I described findings from recent research and research in progress, and also drew upon my experience teaching professional lie catchers. This chapter is not based on scientific evidence. Instead I draw on my personal evaluations informed by thinking about the nature of lying and attempts to apply my research to understanding the larger context in which I live.

Oliver North’s Justification for Lying

At one point in his testimony Lieutenant Colonel North admitted that he had some years earlier lied to Congress about the diversion of Iranian funds to the pro-American Nicaraguan contras. “Lying does not come easy to me,” he said. “But we had to weigh in the balance the difference between lives and lies.” North was citing the classic justification for lying argued in philosophy for centuries. What should you say to a man brandishing a gun who asks, “Where is your brother? I am going to kill him.” This scenario provides no dilemma to most of us. We don’t reveal where our brother is. We lie, giving a false location. As Oliver North said, if life itself is at stake, then you have to lie. A more prosaic example is seen in the instructions parents give to their latch-key children about what to say if a stranger knocks at the door. They are told not to say that they are home alone, but to lie, claiming their parent is taking a nap.

In his book published four years after the congressional hearings, North described his feelings about Congress and the rightness of his cause. “To me, many Senators, Congressmen, and even their staff members were people of privilege who had shamelessly abandoned the Nicaraguan resistance and left the contras vulnerable to a powerful and well-armed enemy. And now they wanted to humiliate me for doing what they should have done! (page 50)... I never saw myself as being above the law, nor did I ever intend to do anything illegal. I have always believed, and still do, that the Boland amendments did not bar the National Security Council from supporting the contras. Even the most stringent of the amendments contained loopholes that we used to ensure that the Nicaraguan resistance would not be abandoned.”1 North acknowledged in his book that he misled members of Congress in 1986 when they tried to find out whether he was directly providing aid to the contras.

North’s lying to defend lives rationale is not justified because, first, it is not certain that his choice was a clear one. He claimed that the contras would die because of the Boland amendments, by which Congress had prohibited, at one point, further “lethal” aid to them. But there was no consensus among experts that withholding such aid would mean the death of the contras. It was a political judgment, one on which most Democrats and most Republicans strongly disagreed. This is not akin to the certainty that the avowed murderer who threatens to kill will do so.

A second objection to North’s claim he was lying to save lives is a problem with who was the target of his lies. He was not lying to the person proclaiming an intent to commit murder. If killing were to occur it would be the Nicaraguan army who would do it, not the members of Congress. While those who disagreed with the Boland amendments might claim that this would be the consequence, it was not the declared intent of those who voted for the Boland amendments, nor could it be said to be the deliberately sought, even if not declared, purpose of that legislation.

Wise and presumably equally moral people disagreed about what would be the consequences of withholding “lethal” aid, and whether the Boland amendments totally closed all loopholes. Zealously, North could not see, or if he saw he did not care, that there was no single truth here to which all rational men and women agreed. North’s hubris was to give his judgment more weight than that of the majority in Congress, and to believe that was a justification for misleading the Congress.

My third objection to North’s rationale that he lied to save lives is that his lie violated a contract he had made which prohibited him from lying to Congress. No one is obligated to answer truthfully an avowed murderer. A murderer’s declared actions violate the laws to which we and he subscribe. Our children have no obligation to be truthful to a stranger knocking at the door, although the matter would become murkier if that stranger claimed to be in distress. Everyone, however, is obligated to testify truthfully before a congressional committee and can be prosecuted for lying. North had additional reasons for being truthful, by virtue of his profession. Lieutenant Colonel North, as a military officer, had sworn to uphold the Constitution. By lying to Congress North violated the constitutionally provided division of responsibility between the two branches of government, specifically the control of the budget that the Constitution gives to Congress as check against the executive’s power to act.2 North was not without recourse if he felt he was being forced to carry out policies which he believed were immorally endangering others. He could have resigned and then publicly spoken out against the Boland amendments.

The argument continues today, as CIA officials who allegedly lied to Congress are now being prosecuted. One question recently discussed in the press is whether there are a special set of rules for CIA officials, who because of the secret nature of their work might not be obligated to be truthful to Congress. Since North was taking orders from CIA director Casey, his actions might be justified as following the norm for employees of that agency. David Whipple, who is the director of the association of former CIA officers, said, “To my mind, to disclose as little as necessary to Congress, if they can get away with it, is not a bad thing. I have trouble myself blaming any of those guys.”3 Ray Cline, also a retired CIA officer, said: “In the old tradition of the CIA we felt that the senior staff officers should be protected from exposure.”4 Stansfield Turner, who was President Jimmy Carter’s director of the CIA from 1977 to 1981, argues that the CIA should not ever be authorized by a president to lie to Congress, and it should be known to agency employees that they will not be protected if they do lie.5

The prosecution of North, Poindexter, and more recently CIA officials Alan Fiers and Clair George, for lying to Congress might convey that message. George is the highest official in the CIA to be prosecuted for lying to the Iran-Contra congressional committee in 1987. Since it is widely believed that CIA director Casey did not follow those rules, one can argue that it is wrong to punish people who were led to believe they were not only doing what the president wanted but would be protected if exposed.

President Richard Nixon and the Watergate Scandal

Former president Nixon is probably the public official who has been most often condemned for lying. He was the first president to resign, but it was not simply because he had lied. Nor was he forced to resign because people working for the White House were caught at the Watergate office and apartment complex in June of 1972 attempting to break in to the Democratic party headquarters. It was the cover-up he directed and the lies he told to maintain it. Audiotapes of conversations in the White House, later made public, revealed Nixon to say at the time, “I don’t give a shit what happens, I want you to stonewall it, let them plead the Fifth Amendment, or anything else, if it’ll save it—save the plan.”

The cover-up did succeed for nearly a year until one of the men convicted for the Watergate break-in, James McCord, told the judge that the burglary was part of a larger conspiracy. Then it came out that Nixon had audio-taped all conversations in the Oval Office. Despite Nixon’s attempt to suppress the most damaging information on those tapes, there was enough evidence for the House Judiciary Committee to bring articles of impeachment. When the Supreme Court ordered Nixon to turn over the tapes to the grand jury, Nixon resigned on August 9, 1974.

The problem, as I see it, was not that Nixon lied, for I maintain that national leaders must sometimes do so; it was what Nixon lied about, his motivation for lying, and to whom he lied. There was no attempt to mislead another government—the target of Nixon’s lie was the American people. There was no possible claim to justification in terms of a need to achieve foreign policy objectives. Nixon concealed his knowledge of a crime, the attempt to steal documents from the Democratic party offices in the Watergate buildings. His motive was to stay in office, to not risk disapproval by the voters if they were to learn that Nixon had known that those who worked for him had broken the law in order to gain an advantage for him in the upcoming election. The first article of impeachment charged Nixon with obstructing justice, the second article charged him with abusing the powers of his office and failing to insure that the laws are faithfully executed, and the third article charged Nixon with deliberately disobeying subpoenas for the tape recordings and other documents from the Judiciary Committee. We should not simply condemn Nixon because he was a liar, although that was a frequent charge jubilantly made by Nixon-haters. National leaders could not do their job if they were prohibited from lying in every circumstance.

President Jimmy Carter’s Justified Lie

A good example of a circumstance in which lying by a public official was justifiable happened during former president Jimmy Carter’s term of office. In 1976, former governor of Georgia Jimmy Carter was elected president after defeating Gerald Ford who had become president when Nixon resigned. In the election campaign Carter promised to restore morality to the White House, after the trying and scandalous Watergate years. The hallmark of his campaign was looking into the television cameras and saying, rather simplistically, that he would never lie to the American people. Three years later, though, he lied many times to conceal his plans to rescue American hostages from Iran.

During the early years of Carter’s presidency, the Shah of Iran was overthrown by a fundamentalist Islamic revolution. The Shah had always received American support, so when he went into exile Carter allowed him to come to the United States for medical treatment. Infuriated, Iranian militants seized the U.S. Embassy in Teheran, taking sixty hostages. Diplomatic efforts to settle the hostage crisis went on for months with no results, while newscasters on television each night counted out the number of days, then months, that Americans were being held as prisoners.

Very soon after the hostages were seized, Carter secretly ordered the military to begin training for a rescue operation. That preparation was not simply concealed, but administration representatives repeatedly made false statements to downplay any suspicions about what they were up to. For many months the Pentagon, the state department, and the White House repeatedly claimed that a mission to free the hostages was logistically impossible. On January 8, 1980, President Carter lied at a press conference, saying that a military rescue “would almost certainly end in failure and almost certainly end in the death of the hostages.” As he was saying this the Delta military force was rehearsing the rescue operation hidden in the south-western desert of the United States.

Carter lied to the American people because he knew the Iranians were listening to what he said, and he wanted to lull the Iranian militants guarding the hostages into a false sense of security. Carter had his press secretary Jody Powell deny that the government was planning to rescue the hostages at the very moment when that rescue mission was in progress. Carter wrote in his memoirs, “Any suspicion by the militants of a rescue attempt would doom the effort to failure . . . Success depended upon total surprise.6” Remember that Hitler also lied to gain the advantage of surprise over an adversary. We condemn Hitler not because he lied but because of his goals and actions. Lying by a national leader to gain an advantage over an enemy is not in and of itself wrong.

The primary target of Carter’s lies was the Iranians who had violated international law by taking hostage U.S. Embassy staff. There was no way to deceive them without deceiving the American people and Congress. The motive was to protect our own military force. And the lie was to be short-lived. Although some members of Congress raised the question of whether Carter had been entitled to act without notifying them in advance, as called for by the War Powers Resolution, Carter claimed that the rescue had been an act of mercy, not an act of war. Carter was condemned because the rescue mission failed, not because he had broken his promise not to lie.

Stansfield Turner, CIA director under Carter, writing about the Iran-Contra affair and the need for CIA officials to be honest with Congress, raised the question about what he would have done if Congress had asked him if the CIA was preparing a rescue operation: “I would have been hard-pressed as to how to respond. I hope I would have said something like, ‘I believe it is inadvisable to talk about any plans for solving the hostage problem, lest incorrect inferences be drawn and possibly leaked to the Iranians.’ I would then have consulted with the president about whether I should return and respond to the question forth-rightly.”7 Mr. Turner does not say what he would have done if President Carter had instructed him to return to Congress and deny that there were any plans to rescue the hostages.

Lyndon Johnson’s Lies about the Viet Nam War

More dangerous was former president Lyndon B. Johnson’s concealment from the public of adverse information about the progress of the war in Viet Nam. Johnson had succeeded to the presidency after the 1963 assassination of John F. Kennedy, but he ran for election in 1964. During the campaign Johnson’s Republican opponent Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater said he might be willing to use atomic weapons to win the war. Johnson took the opposite line. “We are not about to send American boys nine or ten thousand miles away from home to do what Asian boys ought to be doing for themselves.” Once elected, and convinced that the war could be won by sending troops, Johnson sent a half million American boys to Viet Nam over the next few years. America ended up dropping more bombs on Viet Nam than had been used throughout World War II.

Johnson thought he would be in a strong position to negotiate a proper end to the war only if the North Vietnamese believed that he had American public opinion behind him. And so Johnson selected what he revealed to the American people about the war’s progress. His military commanders learned that Johnson wanted the best possible picture of American success and North Vietnamese and Viet Cong failures, and after a time that was the only information he received from field commanders in Viet Nam. But the charade came down when in January 1968 a devastating North Vietnamese and Viet Cong offensive during the holiday season of Tet exposed to Americans and the world how far the U.S. was from winning that war. The Tet offensive occurred during the next presidential election campaign. Senator Robert Kennedy, who was running against Johnson for the Democratic nomination, said that the Tet offensive “shattered the mask of official illusion, with which we have concealed our true circumstances, even from ourselves.” A few months later Johnson announced his decision not to run for reelection.

In a democracy there is no easy way to mislead another nation without misleading your own people, and that makes deception a very dangerous policy when practiced for long. Johnson’s deceit about the progress of the war was not a matter of days, or weeks, or even months. By creating the illusion of imminent victory Johnson deprived the electorate of information they needed to make informed political choices. A democracy cannot survive if one political party can control the information the electorate has about a matter crucial to their vote.

As Senator Kennedy noted, I suspect that another cost of this deceit was that Johnson and at least some of his advisers almost came to believe in their own lies. It is not just government officials who are susceptible to this trap. I believe that the more often anyone tells a lie, the easier it becomes to do so. Each time a lie is repeated there is less consideration about whether it is right to engage in the deceit. After many repetitions, the liar may become so comfortable with the lie that he no longer takes note of the fact that he is lying. If prodded or challenged, however, the liar will remember that he is fabricating. Although Johnson wanted to believe in his false claims about the war’s progress, and may have at times thought they were true, I doubt that he ever succeeded in fully deceiving himself.

The Space Shuttle Challenger Disaster and Self-Deception

To say one has deceived oneself is quite a different matter. In self-deceit the person does not realize that he is lying to himself. And the person does not know his own motive for deceiving himself. Self-deception occurs, I believe, much more rarely than it is claimed by a culpable person to excuse, after the fact, his wrong actions. The actions which led up to the Challenger space shuttle disaster raise the issue of whether those who made the decision to launch the shuttle despite strong warnings about likely dangers might have been the victims of self-deceit. How else can we explain the decision by those who knew the risks to go ahead with the launch?

The space shuttle launch on January 28, 1986, was seen by millions on television. This launch had been highly publicized because the crew included a schoolteacher, Christa McAuliffe. The television audience included many schoolchildren including Ms. McAuliffe’s own class. She was to have given a lesson from outer space. But just seventy-three seconds after launch, the shuttle exploded killing all seven on board.

The night before the launch a group of engineers at Morton Thiokol, the firm that had built the booster rockets, officially recommended that the launch be delayed because the cold weather forecast for overnight might severely reduce the elasticity of the rubber O-ring seals. If that were to happen, leaking fuel might cause the booster rockets to explode. The engineers at Thiokol called the National Aeronautic and Space Administration (NASA), unanimously urging postponement of the launch scheduled for the following morning.

There had already been three postponements in the launch date, violating NASA’s promise that the space shuttle would have routine, predictable launch schedules. Lawrence Mulloy, NASA’s rocket project manager, argued with the Thiokol engineers, saying there was not enough evidence that cold weather would harm the O-rings. Mulloy talked that night to Thiokol manager Bob Lund, who later testified before the presidential commission appointed to investigate the Challenger disaster. Lund testified that Mulloy told him that night to put on his “management hat” instead of his “engineering hat.” Apparently doing so, Lund changed his opposition to the launch, overruling his own engineers. Mulloy also contacted Joe Kilminister, one of the vice presidents at Thiokol, asking him to sign a launch go-ahead. He did so at 11:45 PM, faxing a launch recommendation to NASA. Allan McDonald, who was director of Thiokol’s rocket project, refused to sign the official approval for the launch. Two months later McDonald was to quit his job at Thiokol.

Later the presidential commission discovered that four of NASA’s key senior executives responsible for authorizing each launch never were told of the disagreement between Thiokol engineers and the NASA rocket management team on the night the decision to launch was made. Robert Sieck, shuttle manager at the Kennedy Space Center; Gene Thomas, the launch director for Challenger at Kennedy; Arnold Aldrich, manager of space transportation systems at the Johnson Space Center in Houston; and Shuttle director Moore all were to later testify that they were not informed that the Thiokol engineers opposed a decision to launch.

Crew of the spaceship Challenger

How could Mulloy have sent the shuttle up knowing that it might explode? One explanation is that under pressure he became the victim of self-deceit, actually becoming convinced that the engineers were exaggerating what was really a negligible risk. If Mulloy was truly the victim of self-deceit can we fairly hold him responsible for his wrong decision? Suppose someone else had lied to Mulloy and told him there was no risk. We certainly would not blame him for then making a wrong decision. Is it any different if he has deceived himself? I think probably not, if Mulloy truly has deceived himself. The issue is, was it self-deception or bad judgment, well rationalized?

To find out let me contrast what we know about Mulloy with one of the clear-cut examples of self-deceit discussed by experts who study self-deception.8 A terminal cancer patient who believes he is going to recover, even though there are many signs of a rapidly progressing, incurable malignant tumor, maintains a false belief. Mulloy also maintained a false belief, believing the shuttle could be safely launched. (The alternative that Mulloy knew for certain that it would blow up I think should be ruled out.) The cancer patient believes he will be cured, despite the contrary strong evidence. The cancer patient knows he is getting weaker, the pain is increasing, but he insists these are only temporary setbacks. Mulloy also maintained his false belief despite the contrary evidence. He knew the engineers thought the cold weather would damage the O-ring seals, and if fuel leaked the rockets might explode, but he dismissed their claims as exaggerations.

What I have described so far does not tell us whether either the cancer patient or Mulloy is a deliberate liar or the victim of self-deceit. The crucial requirement for self-deceit is that the victim is unaware of his motive for maintaining his false belief.* The cancer patient does not consciously know his deceit is motivated by his inability to confront his fear of his own imminent death. This element—not being conscious of the motivation for the self-deceit—is missing for Mulloy. When Mulloy told Lund to put on his management hat, he showed that he was aware of what he needed to do to maintain the belief that the launch should proceed.

Richard Feynman, the Nobel laureate physicist who was appointed to the presidential commission which investigated the Challenger disaster, wrote as follows about the management mentality that influenced Mulloy. “[W]hen the moon project was over, NASA . . . [had] to convince Congress that there exists a project that only NASA can do. In order to do so, it is necessary—at least it was apparently necessary in this case—to exaggerate: to exaggerate how economical the shuttle would be, to exaggerate how often it could fly, to exaggerate how safe it would be, to exaggerate the big scientific facts that would be discovered.”9 Newsweek magazine said, “In a sense the agency seemed a victim of its own flackery, behaving as if space-flight were really as routine as a bus trip.”

Mulloy was just one of many in NASA who maintained those exaggerations. He must have feared congressional reaction if the shuttle had to be delayed a fourth time. Bad publicity which contradicted NASA’s exaggerated claims about the shuttle might affect future appropriations. The damaging publicity from another postponed launch date might have seemed a certainty. The risk due to the weather was only a possibility, not a certainty. Even the engineers who opposed the launch were not absolutely certain there would be an explosion. Some of them reported afterwards thinking only seconds before the explosion that it might not happen.

We should condemn Mulloy for his bad judgment, his decision to give management’s concerns more weight than the engineers’ worries. Hank Shuey, a rocket-safety expert who reviewed the evidence at NASA’s request, said, “It’s not a design defect. There was an error in judgment.” We should not explain or excuse wrong judgments by the cover of self-deception. We should also condemn Mulloy for not informing his superiors, who had the ultimate authority for the launch decision, about what he was doing and why he was doing it. Feynman offers a convincing explanation of why Mulloy took the responsibility on himself. “[T]he guys who are trying to get Congress to okay their projects don’t want to hear such talk [about problems, risks, etc.]. It’s better if they don’t hear, so they can be more ‘honest’—they don’t want to be in the position of lying to Congress! So pretty soon the attitudes begin to change: information from the bottom which is disagreeable—‘We’re having a problem with the seals; we should fix it before we fly again’—is suppressed by big cheeses and middle managers who say, ‘If you tell me about the seals problems, we’ll have to ground the shuttle and fix it.’ Or, ‘No, no, keep on flying, because otherwise, it’ll look bad,’ or ‘Don’t tell me; I don’t want to hear about it.’ Maybe they don’t say explicitly ‘Don’t tell me,’ but they discourage communication which amounts to the same thing.”10

Mulloy’s decision not to inform his superiors about the sharp disagreement about the shuttle launch could be considered a lie of omission. Remember my definition of lying (in chapter 2, page 26) is that one person deliberately, by choice, misleads another person without any notification that deception will occur. It does not matter whether the lie is accomplished by saying something false or by omitting crucial information. Those are just differences in technique, for the effect is the same.

Notification is a crucial issue. Actors are not liars but impersonators are, for the actor’s audience is notified that a role is to be played. Slightly more ambiguous is a poker game, where the rules authorize certain types of deceit such as bluffing, and real estate sales where no one should expect sellers to reveal truthfully at the outset their real selling price. If Feynman is correct, if the NASA higher-ups had discouraged communication, essentially saying, “Don’t tell me,” then this might constitute notification. Mulloy and presumably others at NASA knew that bad news or difficult decisions were not to be passed to the top. If that was so then Mulloy should not be considered a liar for not informing his superiors, for they had authorized the deceit, and knew they would not be told. In my judgment the superiors who were not told share some of the responsibility for the disaster with Mulloy who did not tell them. The superiors have the ultimate responsibility not only for a launch decision but for creating the atmosphere in which Mulloy operated. They contributed to the circumstances which led to his bad judgment, and for his decision not to bring them in on the decision.

Feynman notes the similarities between the situation at NASA and how mid-level officials in the Iran-Contra affair, such as Poindexter, felt about telling President Reagan what they were doing. Creating an atmosphere in which subordinates believe that those with ultimate authority should not be told of matters for which they would be blamed, providing plausible deniability to a president, destroys governance. Former president Harry Truman rightly said, “The buck stops here.” The president or chief executive officer must monitor, evaluate, decide, and be responsible for decisions. To suggest otherwise may be advantageous in the short run, but it endangers any hierarchal organization, encouraging loose cannons and an environment of sanctioned deceit.

Judge Clarence Thomas and Professor Anita Hill

The widely conflicting testimony by Supreme Court nominee Judge Clarence Thomas and law professor Anita Hill in the fall of 1991 offers a number of sobering lessons about lying. The dramatic televised confrontation began just days before the Senate was expected to confirm Thomas’s nomination to the Supreme Court. Professor Hill testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee that between 1981 and 1983, when she was an assistant to Clarence Thomas, first in the Office of Civil Rights in the Department of Education, and then when Thomas became head of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission, she had been the victim of sexual harassment. “He spoke about acts that he had seen in pornographic films involving such matters as women having sex with animals and films showing group sex or rape scenes. . . . He talked about pornographic materials depicting individuals with large penises or large breasts involved in various sex acts. On several occasions Thomas told me graphically of his own sexual prowess.... He said that if I ever told anyone of his behavior, that it would ruin his career.” She spoke with absolute calm, she was consistent and to many observers very convincing.

Immediately after her testimony Judge Thomas totally denied all her charges: “I have not said or done the things Anita Hill has alleged.” After Hill’s testimony Thomas said, “I would like to start by saying unequivocally, uncategorically, that I deny each and every single allegation against me today.” Self-righteously angry at the committee for injuring his reputation, Thomas claimed he was the victim of a racially motivated attack. He continued: “I cannot shake off these accusations because they play to the worst stereotypes we have about black men in this country.” Complaining about the ordeal the Senate had put him through, Thomas said, “I would have preferred an assassin’s bullet to this kind of living hell.” The hearing, he said, was “a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks.”

Time magazine’s banner headline that week read: “As the nation looks on, two credible articulate witnesses present irreconcilable views of what happened nearly a decade ago.” Columnist Nancy Gibbs wrote in Time: “Even after listening to all the anguished testimony, who could ever feel confident that they knew what really happened? Which one was a liar of epic proportion?”

My focus is more narrowly on only the behavior shown by Hill and Thomas as each testified, not Thomas’s testimony before the committee prior to the Anita Hill matter, nor either one’s past history or the testimony of other witnesses about each of them. Considering just their demeanor, I found no new or special information. I could only note what was obvious to the press, that each spoke and behaved quite convincingly. But there are some lessons to be learned from this confrontation about lying and demeanor.

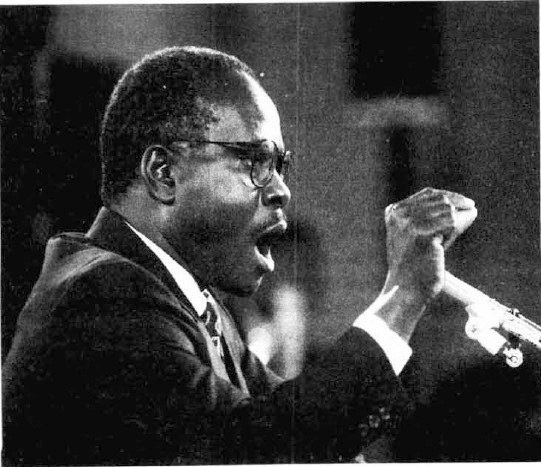

Clarence Thomas

It would not have been easy for either of them to lie deliberately in front of the entire nation. The stakes for both were enormously high. Think what the outcome would have been if either of them had acted in such a way that they were judged, rightly or wrongly, as lying by the media and the American people. That didn’t happen; both looked like they meant it.

Suppose Hill was being truthful and Thomas had decided to lie deliberately. If he had consulted the second chapter in Telling Lies he would have found my advice that the best way to cover the fear of being caught is with a veneer of another emotion. Using the example from John Updike’s book Marry Me, I described on page 33 how the unfaithful wife Ruth could fool her suspicious husband by going on the attack, letting herself become angry and making him defensive for disbelieving her. That is exactly what Clarence Thomas did. His anger was intense, his target was not Anita Hill, but the Senate. He had the additional benefit of enlisting the sympathy of everyone who feels angry at politicians, and of appearing as a David fighting the mighty Goliath.

Just as Thomas would have lost sympathy if he had attacked Hill, the Senators would have lost sympathy if they had then attacked Thomas, a black man who says he is being lynched for being uppity. If he was going to lie it would also make sense for him not to watch Anita Hill’s testimony, so the Senators could not as easily ask him about it.

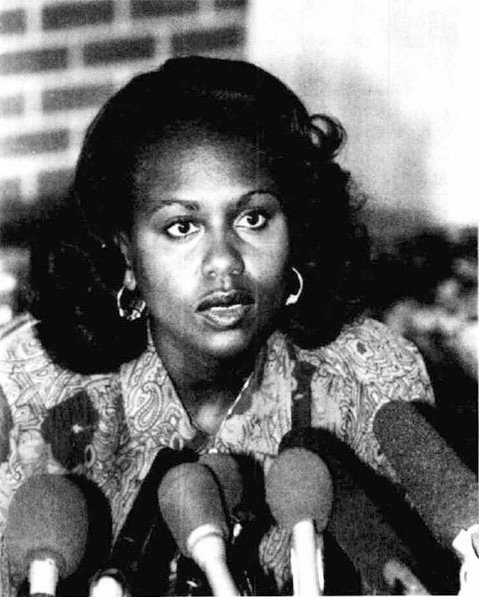

Anita Hill

While this line of reasoning should please those who opposed Thomas before the hearing, it does not prove he was lying. He might well have attacked the Senate committee if he had been telling the truth. If Hill was the liar, Thomas would have every right to be furious at the Senate for listening to her stories, brought up at the very last moment, in public, just when it appeared his political opponents had lost their attempt to block his nomination. If Hill was the liar, Thomas might have been so upset and so angry that he could not have stood watching her testimony on television.

Could Anita Hill have been lying? I think it is unlikely, since if she was, she should have been afraid of being disbelieved, and there was no sign of apprehension. She testified coolly and calmly, with reserve, and little sign of any emotion. But the absence of a behavioral clue to deceit does not mean the person is being truthful. Anita Hill had time to prepare and rehearse her story. It is possible she could do so convincingly, it is just not likely.

Although it is more likely that Thomas is the liar than Anita Hill, there is a third possibility which strikes me as most likely. Neither one told the truth and yet neither one may have been lying. Suppose something did happen, but not as much as Professor Hill said, but more than Judge Thomas admitted. If her exaggeration and his denial were repeated again and again, there would be little chance by the time we saw them testify that either one would any longer remember that what each was saying was not entirely true.

Thomas might have forgotten what he did, or even if he remembers it he remembers a well-sanitized version. His anger about her accusations would then be totally justified. He is not lying, as he sees and remembers it, he is telling the truth. And if there was some reason for Hill to resent Thomas, for some slight or affront, real or imagined, or some other reason, she might over time have come to embroider, elaborate, and exaggerate what actually did happen. She too would be telling the truth as she remembers and believes it to be. This is similar to self-deception, the key difference being that in this case the false belief develops slowly over time, through repetitions which each time slowly are elaborated. Some who write about self-deceit might not think this is a difference which matters much.

There is no way to tell from their demeanor which of these accounts is true—is he the liar, is she the liar, or are they both not telling the entire truth? Yet when people hold strong opinions—about sexual harassment, who should be on the Supreme Court, about Senators, about men, and so forth—it is hard to tolerate not knowing what conclusion to draw. Faced with that ambiguity most people resolve it by becoming quite convinced they can tell from demeanor which one is telling the truth. It is usually the person with whom they were most sympathetic to begin with.

It is not that behavioral clues to deceit are useless, but we should know when they will and won’t be useful, and how to accept when we cannot tell whether someone is truthful or lying. There is a statute of limitations on charges of sexual harassment—ninety days. One of the very good reasons for having that limitation is that the issues are fresher, and behavioral clues to deceit perhaps more detectable. If we had been able to see each of them testify within a few weeks of the alleged harassment, there would have been a much better chance to tell from their behavior which was telling the truth, and perhaps what was charged and denied might have been different.

A Country of Lies

A few years ago I thought America had become a country of lies: from L.B.J.’s lies about the Viet Nam war, the Nixon Watergate scandal, Reagan and Iran-Contra, and the continuing mystery about Senator Edward Kennedy’s role in the death of a woman friend at Chapaquiddick to Senator Biden’s plagiarism and former Senator Gary Hart’s lie during the 1984 presidential campaign about his extramarital affair. It is not just politics; lies in business have come to the fore, in Wall Street and savings and loans scandals, and lies in sports, such as baseball Hall of Fame Pete Rose’s to conceal his gambling and Olympic athlete Ben Johnson’s to conceal his use of drugs. Then I spent five weeks lecturing in Russia in May 1990.

Having been in Russia before, as a Fulbright professor in 1979, I was astonished by how much more frank people now were. They were no longer afraid to talk to an American, or to criticize their own government. “You have come to the right country,” I was often told. “This is a country of lies! Seventy years of lies!” Again and again I was told by Russians how they had always known how much their government had lied to them. Yet in my five weeks there I saw how stunned they were to learn about new lies they had not earlier suspected. A poignant example was the revelation of the truth about the suffering of the people of Leningrad during World War II.

Very soon after Nazi Germany’s invasion of Russia in 1941, the Nazi troops surrounded Leningrad (now St. Petersburg). Their siege lasted 900 days. One and a half million people reportedly died in Leningrad, many of starvation. Nearly every adult I met told me about family members they had lost during the siege. But while I was there the government announced that the figures for the number of civilians who died in the siege had been inflated. On the day in May when the whole country celebrated the victory over the Nazis, the Soviet government announced that casualties in the war had been so high because there were not enough officers to command the Soviet troops. Soviet leader Stalin, the government said, had murdered many of his own officers in a purge before the war began.

It is not just the revelation of past unsuspected lies, but new lies continue. Just a year after Mikhail Gorbachev came to power there was a disastrous nuclear accident at Chernobyl. A radiation cloud spread over parts of Western as well as Eastern Europe, but the Soviet government at first revealed nothing. Scientists in Scandinavia recorded high levels of radiation in the atmosphere. Three days later Soviet officials admitted a large accident had occurred and said that thirty-two people had died. Only after several weeks had elapsed did Gorbachev speak publicly, and he spent most of his time criticizing the Western reaction. The government has never admitted that people in the area were not evacuated early enough and many suffered from radiation sickness. Russian scientists now estimate that as many as 10,000 may die from the Chernobyl accident.

I learned about this from a Ukrainian physician who shared my compartment on the overnight train to Kiev. Communist party officials had evacuated their families, he said, while everyone else was told it was safe to stay. This physician was now treating young girls with ovarian cancer, a disease normally not seen in such young people. On the ward for children suffering from radiation sickness, their bodies glowed at night. I was not able to be certain, because of our language difficulty, whether he was speaking literally or metaphorically. “Gorbachev lies to us like the rest of them,” he said. “He knows what has happened and he knows that we know he is lying.”

I met a psychologist who had been assigned to interview those living in the vicinity of Chernobyl, to evaluate how they were dealing with the stress three years later. He thought their plight would be partially alleviated if they did not feel so abandoned by their government. His official recommendation was for Gorbachev to speak to the nation and say, “We made a terrible mistake, underestimating the severity of the radiation. We should have evacuated many more of you and much more quickly, but we had no place to put you. And once we learned about our mistake we should have told you the truth and we didn’t. Now we want you to know the truth and to know that the nation suffers for you. We will give you the medical care you need and our hopes for your future.” His recommendation went unanswered.

Anger about the lies about Chernobyl is not over. Early in December of 1991, more than five years after the accident, the Ukrainian parliament demanded that Mikhail Gorbachev and seventeen other Soviet and Ukrainian officials be prosecuted. The chairman of the Ukrainian legislative commission which investigated the incident, Volodymyr Yavorivsky, said, “All the leadership, from Gorbachev down to the decipherers of coded telegrams, were aware of the level of active radioactive contamination.” The Ukrainian leaders said that President Gorbachev “had personally covered up the extent of radiation leakage.”

For decades Soviets learned that to achieve anything they had to bend and evade the rules. It became a country in which lying and cheating were normal, where everyone knew the system was corrupt and the rules unfair, and survival required beating the system. Social institutions cannot work when everyone believes every rule is to be broken or dodged. I am not convinced that any change in government will quickly change such attitudes. No one now believes what anyone in the current government says about anything. Few I met believed Gorbachev, and that was a year before the 1991 failed coup. A nation cannot survive if no one believes what any leader says. This may be what makes a population willing, eager perhaps, to give their allegiance to any strong leader whose claims are bold enough, and actions strong enough, to win back trust.

Americans joke about lying politicians—“How can you tell when a politician is lying? When he moves his lips!” My visit to Russia convinced me that, by contrast, we still expect our leaders to be truthful even though we suspect they will not be. Laws work when most people believe they are fair, when it is a minority not the majority who feel it is right to violate any law. In a democracy, government only works if most people believe that most of the time they are told the truth, and that there is some claim to fairness and justice.

No important relationship survives if trust is totally lost. If you discover your friend has betrayed you, lied to you repeatedly for his own advantage, that friendship cannot continue. Neither can a marriage be more than a shambles if one spouse learns that the other, not once but many times, has again and again been a deceiver. I doubt any form of government can long survive except by using force to oppress its own people, if the people believe its leaders always lie.

I don’t think we have come to that. Lying by public officials is still newsworthy, condemned not admired. Lies and corruption are part of our history. They are nothing new, but they are still regarded as the aberration not the norm. We still believe we can throw the rascals out.

While Watergate and the Iran-Contra affair can be viewed as proof that the American system has failed, we can also see them as proof of just the opposite. Nixon had to resign. When Supreme Court Chief Justice Warren Burger administered the oath of office to Gerald Ford to replace Nixon, he said to one of the Senators present, “It [the system] worked, thank God it worked.”11 North, Poindexter, and now others are prosecuted for lying to the Congress. During the Iran-Contra Congressional hearings, Congressman Lee Hamilton chastised Oliver North with a quotation from Thomas Jefferson: “The whole art of government consists in the art of being honest.”

* It might seem that self-deceit is just another term for Freud’s concept of repression. There are at least two differences. In repression the information concealed from the self arises from a deep-seated need within the structure of the personality, which is not typically the casein self-deception. And some maintain that confronting the self-deceiver with the truth can break the deceit, while in repression such a confrontation will not cause the truth to be acknowledged. See discussion of these issues in Lockard and Paulhus, Self-Deception.