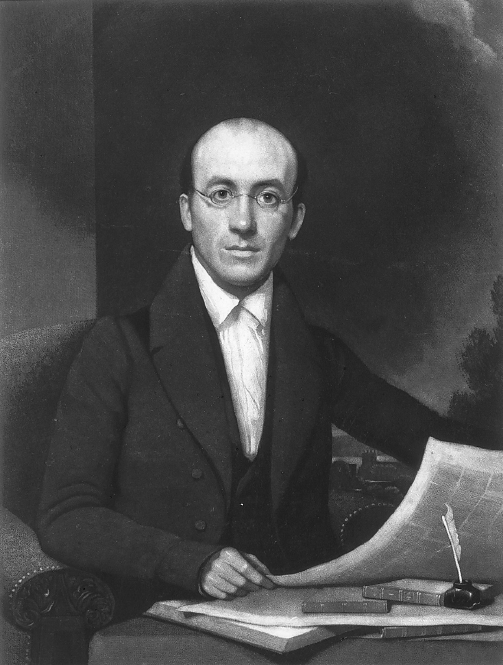

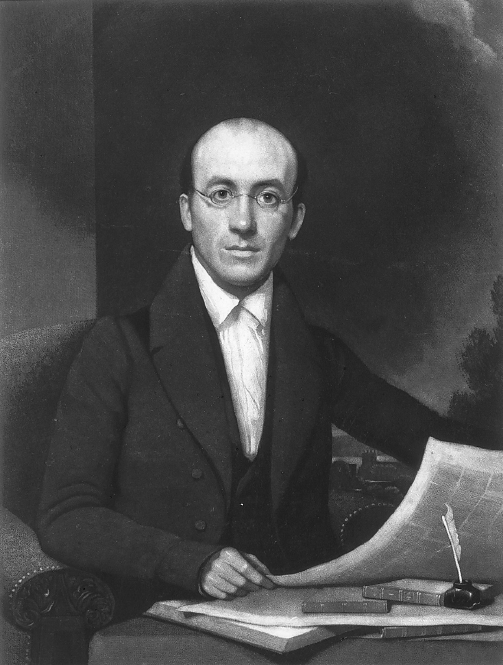

From his position as editor of The Liberator, William Lloyd Garrison emerged as the chief prophet of the Abolition Movement. (Courtesy of Boston Public Library)

In the early decades of the nineteenth century, economic factors related to the issue of slavery developed to create a geographic fault line that divided the United States into two distinct sections. The North began to industrialize, with the rapid growth of urban-based factories producing a broad range of consumer products; the South retained its largely agrarian economy that relied on the production of cotton and tobacco, both of which rested squarely on the back of slave labor.

To the religious zealots at the vanguard of the Abolition Movement, even more important than the economic dimension of slavery was the moral one. To these highly committed and often self-righteous men and women, slavery was abhorrent not merely because it exploited Africans who had been captured and brought to America but also because slaves could not benefit from the fruits of their own labor, were not guaranteed the right to participate in the domestic relations of marriage and parenthood, and were not allowed to control their conduct in sufficient degree to prepare the immortal soul for eternity. So in the eyes of the abolitionists, slaves were denied the opportunity to live their lives as the children of God. Slavery was a sin.

Southern apologists saw the institution of slavery from a strikingly different perspective. They argued that slave owners introduced Americans of African descent to Christianity and civilized behavior, while also guaranteeing this helpless and dependent people—the vast majority of whites believed that black people were so intellectually inferior that they were closer to animals than human beings—the food, clothing, shelter, and security during sickness and old age that northern factory workers were ruthlessly denied.

Abolitionists intent upon propagating their point of view chose the newspaper as their primary method of communication for two reasons. First, newspapers could bridge the geographic gaps that separated anti-slavery advocates from each other, helping to build and galvanize a unified social movement. By publicizing upcoming activities, reprinting speeches and minutes from meetings and conventions, and publishing news items about movement leaders, anti-slavery newspapers could help build a national abolitionist community and then keep the faithful united.

Second, abolitionists were committed to the power of moral suasion. They sincerely believed that all Americans were reasonable people who, when the sinful nature of slavery was explained to them, would immediately support the nation cleansing itself of the dastardly institution, regardless of the economic consequences. Newspapers offered a venue in which to articulate that information to the sons and daughters of democratic thinking.

Because slavery and its inevitable collision of economics and morality created the most contentious issue of the era, mainstream newspapers opted not to devote a great deal of space to the topic, certainly not as much space as abolition leaders wanted. So those resolute men and women created their own communication network. Dozens of abolitionist papers, most of them based and distributed in the North, were published between 1800 and 1865.

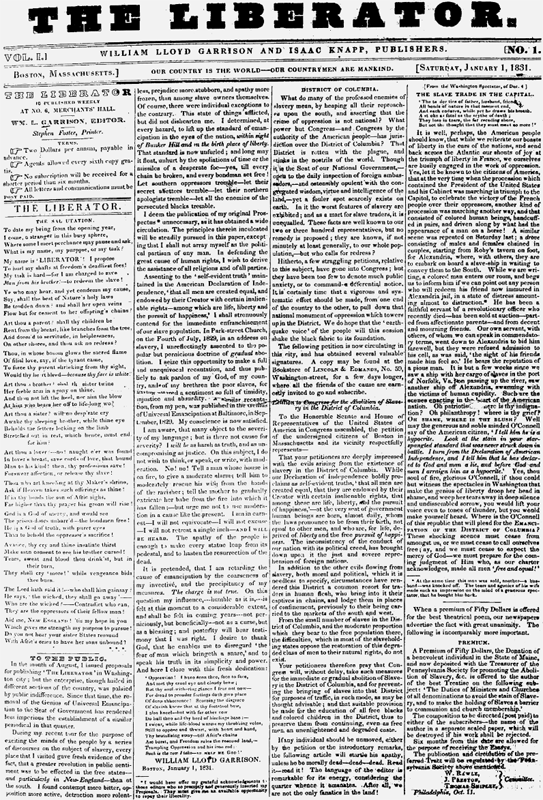

By far the best known and most influential of the anti-slavery newspapers was The Liberator. Founded in 1831 and published without interruption for thirty-five years—ceasing publication only after slavery was abolished in 1865—this cacophonous advocacy journal dominated the genre like no other. Thanks to William Lloyd Garrison, the paper’s bombastic editor and chief prophet of the abolition crusade in the United States, The Liberator became synonymous with the abolitionist press. In addition to filling the Boston weekly’s four pages with strident commentary, Garrison devised innovative techniques to ensure that his paper became the focal point of the entire Abolition Movement. Today The Liberator is remembered, and rightly so, as the epitome of dissident journalism in American history.

WILLIAM LLOYD GARRISON:

DIEHARD ABOLITIONIST EDITOR

Garrison was born into a working-class family in Newburyport, Massachusetts, in 1805. Poverty forced young William to leave school at the age of ten and become an apprentice printer whose classroom was the pressroom—his education was confined to reading the lead type in the printing press. While helping abolitionist Benjamin Lundy edit the Genius of Universal Emancipation during the 1820s, Garrison grew increasingly vehement in his attacks on American slave traders, raging against the barbarities they routinely performed—kidnap, rape, murder.

From his position as editor of The Liberator, William Lloyd Garrison emerged as the chief prophet of the Abolition Movement. (Courtesy of Boston Public Library)

In 1829, Garrison undertook a journalistic campaign against Francis Todd, who transported slaves to Louisiana sugar plantations aboard his ship, the Francis. Under the heading “Black List,” Garrison denounced Todd for mistreating his slaves. “Any man can gather up riches, if he does not care by what means they are obtained,” Garrison wrote. “The Francis carried off seventy-five slaves, chained in a narrow place between decks.” Todd sued Garrison for libel, charging that the slaves had not been chained but had been free to move below deck—in fact, had been allowed to conduct their own daily prayer meetings—and that Garrison had relied on hearsay for his article. The jury agreed with Todd. Garrison probably could have avoided a jail sentence if he had shown any sign of remorse, but he did not.1

After serving forty-nine days behind bars, Garrison moved to Boston, and on January 1, 1831, he founded what soon became the country’s most visible and volatile journalistic adversary of chattel slavery. The Liberator’s editor was a single-minded man of courage and conviction who was destined to preach the anti-slavery credo to an entire generation of Americans.

Garrison was irascible and sometimes irresponsible, a man imbued with righteous indignation. Most abolitionists acknowledged the South’s economic dependence on slavery and therefore were willing to compromise by supporting gradual emancipation over a period of several years—first in the border states, eventually in the Deep South. But Garrison would have none of it; he demanded nothing less than immediate and total freedom for all slaves. “I will be as harsh as truth and as uncompromising as justice,” he wrote in the militant manifesto that appeared in his inaugural issue. “On this subject, I do not wish to think, or speak, or write, with moderation. No! No! Urge me not to use moderation in a cause like the present. I am in earnest—I will not equivocate—I will not excuse—I will not retreat a single inch—AND I WILL BE HEARD.”2

One of the most controversial themes to erupt in the pages of The Liberator involved Garrison’s stand on violence. Although he preached Christianity and swore that he was committed to peaceful activism only, his critics charged that the editor encouraged slaves to revolt against their owners. Some of Garrison’s rhetoric did, indeed, seem to promote violence. Typical was the message communicated in a verse titled “The Insurrection”:

Woe if it come with storm, and blood, and fire,

When midnight darkness veils the earth and sky!

Woe to the innocent babe—the guilty sire—

Mother and daughter—friends of kindred tie!

Stranger and citizen alike shall die!3

Such statements understandably made Garrison unpopular among people who continued to support slavery, and in the 1830s and 1840s the vast majority of Americans remained securely in that camp. One of The Liberator’s early letters to the editor read, “Your paper cannot much longer be tolerated. Shame on the freemen of Boston for permitting such a vehicle of outrage and rebellion to spring into existence among them!” Other letters contained obscenities so foul that the mores of the time dictated that the caustic words be replaced with dashes. One screamed, “O! you pitiful scoundrel! you toad eater! you d—d son of a——! hell is gaping for you! the devil is feasting in anticipation! you are not worth——.”4

But when Garrison received such letters, he did not shudder in fear; he rejoiced. Opting for a route that would be followed by many of the dissident editors who would follow him, Garrison reprinted the charges. The angry letters became so voluminous, in fact, that The Liberator began carrying a weekly section set aside specifically for them.

Garrison published the letters because one of The Liberator’s hallmarks, as in the labor press, was providing an open forum in which readers—those who agreed with the editor as well as those who did not—could voice their opinions. Garrison, never a modest man, boasted that his paper “admitted its opponents to be freely and impartially heard through its columns—as freely as its friends. I have set an example of fairness and magnanimity, in this respect, such as has never been set before.”5

Proof of Garrison’s pledge to provide an open forum came in the form of the letters from the opposition that he published in The Liberator—most of them on the front page. In one, a slavery advocate argued that the Bible “beyond all question” endorsed slavery; in another, the author called abolitionists “instigators of treason.” Garrison was a favorite target of many of the writers. He was, at various times, labeled a “fanatical traitor” and “as mad as the winds”; on another occasion, a letter writer demanded that the radical editor be hanged.6

In addition to the emotional pain resulting from such ad hominem attacks, Garrison made other personal sacrifices. He often worked sixteen hours a day, six days a week in a small, dingy office—only tiny streams of light entering through ink-spattered windows. Besides writing his fiery editorials, he also set the type, operated the press, wrote the addresses of subscribers on the printed papers, and delivered the bundles to the post office. In his early days as an editor, the gaunt and bespectacled Garrison, who was twenty-five years old when he founded The Liberator, lived chiefly on water and stale bread from a nearby bakery.

Garrison’s paper was rag-tag in appearance. The layout was erratic, with readers complaining that articles were thrown in “higgledy-piggledy.” Issues were rarely complete; matters were often left at loose ends with the promise of “more next week”—but that promise went unfulfilled. The time lag between news stories on page one and editorials on page three often stretched to several weeks, and many important elections passed without Garrison ever finding the time to comment on them.7

Finances were another problem. The Liberator carried only a few small advertisements—for books, medicines, boarding houses—and therefore received scant revenue from the monetary mainstay of most publications. Nor did The Liberator attract substantial revenue from circulation; the initial print run was only 400, and the number of persons paying the two dollars for an annual subscription never exceeded 2,500. Garrison paid his printing and mailing costs primarily from the fees that he charged for giving lectures. He was much in demand as a speaker, averaging one public address a week through the three and a half decades he published The Liberator, partly because slavery supporters enjoyed publicly humiliating him. For the passionate words that he spoke, most of them having previously appeared in his newspaper, were almost always accompanied by jeering and heckling from pro-slavery demonstrators. “They came equipped with rotten eggs and brickbats, firecrackers and other missiles,” he wrote matter-of-factly after being pelted with eggs during a speech in Pennsylvania. “One of the eggs bespattered my head and back somewhat freely.”8

Garrison endured the attacks because he was convinced that he had been placed on this Earth to free the slaves and that The Liberator was the tool best suited to awakening apathetic Americans to their sins. “The people, at large, are astonishingly ignorant of the horrors of slavery,” he wrote. “Let information be circulated among them, and they cannot long act and reason as they now do.”9

To save his newspaper from financial ruin, in 1832 Garrison founded the New England Anti-Slavery Society and, a year later, the American Anti-Slavery Society. He hoped that contributions from the two groups would give The Liberator fiscal stability. Garrison’s revenue-raising strategy only partially succeeded, though, because many diehard abolitionists questioned whether publishing a radical newspaper of such small circulation was judicious use of the movement’s limited resources.10

And yet, despite the small number of subscribers and lukewarm support of many movement leaders, there is no question that The Liberator influenced the nation’s attitude toward slavery. “I have seen my principles embraced, cordially and unalterably, by thousands of the best men in the nation,” the immodest Garrison wrote in 1834. “What else but the Liberator primarily (and of course instrumentally) has effected this change? Greater success no man could obtain.”11

The most salient indication of the influence that the paper was having on the American conscience came not from Garrison’s boasting but from the numerous governmental bodies that took extreme measures in hopes of preventing The Liberator’s publication and distribution. The Georgia legislature offered a bounty of $5,000 to anyone who kidnapped and brought Garrison before the legislators to answer for his misdeeds, and a group of slave owners in Mississippi later upped that ante to $20,000. Elected officials in South Carolina offered a reward to any person who apprehended Liberator distributors, and the city of Georgetown in the District of Columbia was among several jurisdictions that made it illegal for free blacks to read the paper. On the federal level, Postmaster General Amos Kendall openly condoned southern vigilante groups that rifled mail sacks to destroy copies of The Liberator.12

Today The Liberator, published each week for thirty-five years, is remembered as the archetype of dissident journalism in America.

Boston took its own action. On several occasions, pro-slavery townspeople showed their hatred of Garrison by erecting a gallows in front of his office. Then, in the fall of 1835, a mob of some 100 men assembled outside a hall where the editor was speaking and threatened to tar and feather him. Fearing for his safety, Garrison slipped out a back window and sought refuge in a carpenter shop where he hid behind a pile of lumber. The crowd tracked him down, looped a rope around his neck, and dragged him through the streets of Boston as onlookers screamed, “Lynch him!” Several men then stripped Garrison naked, carried him to the second floor of a building and, with the rope still coiled around his neck, threatened to hang him by hurling him out an open window. Just as the mob was poised to end Garrison’s irritating behavior once and for all, a delegation of moderate abolitionists came to his rescue.13

Such acts of intimidation did not cause Garrison’s radicalism to abate—but to escalate. At the same time that the nation’s more even-tempered statesmen struggled to forge a road of compromise that would keep the North and the South united as a single nation, Garrison used The Liberator to demand an opposite route. Fully fifteen years before the Civil War finally ripped the country apart, the dissident paper insisted that readers could no longer pledge their allegiance to a slaveholding government and that all non-slaveholders must secede from the union. “The existing national compact should be instantly dissolved,” Garrison wrote in 1844. “Secession from the government is a religious and political duty. The motto inscribed on the banner of Freedom should be, NO UNION WITH SLAVEHOLDERS.”14

As the years passed and the nation’s leading politicians continued to strive to preserve the fragile peace, Garrison became increasingly outspoken in his support of violence. In 1859 after radical abolitionist John Brown led his band of rebels in an attack on the U.S. military arsenal at Harper’s Ferry, virtually every newspaper in the country—including most abolitionist papers—condemned Brown’s action, which had led to the deaths of ten men. Garrison, to the contrary, praised Brown as a man of courage for killing other white men in the cause of ending slavery. After Brown was captured and hanged, Garrison wrote: “I cannot but wish success to all slave insurrections.”15

Although The Liberator certainly was not the sole catalyst for the armed conflict between the North and the South, the strident statements that the newspaper disseminated clearly hastened the division among the American people on the slavery issue. By identifying abolition as a struggle between an open society with a free intellectual market and a closed society that feared change and new ideas, The Liberator exposed the American people to the disconnect between the bedrock democratic ideals that the United States had been founded on and the unjust treatment it continued to mete out to Americans of African descent.

By the mid-1840s, Garrison had not only a journalistic venue in which to preach his gospel of abolition, but also a domestic one. He married Helen Eliza Benson, who then joined her husband in inviting prospective abolitionists into the Garrison home—she filled their stomachs with beef and biscuits; he filled their heads with items he read aloud from The Liberator. The combination of generous hospitality and unrelenting rhetoric proved so successful in adding converts to the cause, in fact, that wealthy abolition leaders began stocking Helen Garrison’s pantry. “I see you have a houseful of people,” one supporter scribbled on a note attached to a barrel of flour. “Your husband’s position brings him many guests and expenses.” She accepted the contributions gladly, as the constant stream of visitors to feed and the growing Garrison family to care for—she had seven children—on her husband’s paltry income was taxing. The Garrisons drifted from one house to another until 1855 when a supporter gave them a house to provide a permanent address for what some observers dubbed the “Garrison Anti-Slavery Hotel.”16

MISSION ACCOMPLISHED

Garrison welcomed the Civil War as a necessary step toward freeing the slaves; soon after the fighting began, he headlined one front-page story “Hurrah for the War!” Although the dissident journalist never went to the battlefront, he wrote articles about the war as if he had. Describing the Confederate soldiers as “debased and dastardly minions of the Slave Power,” he crafted exaggerated passages about how Union soldiers were being savagely abused. “We hear of the wounded on the battlefield thrust through and through with bowie-knives and bayonets, and otherwise mangled—in some instances their bodies quartered, and in others their heads cut off, and made foot-balls of by their fiendish enemies.”17

More than 600,000 Americans died in the Civil War, the most wrenching and costly event—in the human terms of the number of lives lost and the number of families destroyed—in the history of the nation. And then finally, after four years of battle, General Robert E. Lee surrendered at Appomattox in the spring of 1865 to bring an end to the fighting, and ratification of the Thirteenth Amendment to the Constitution later that year abolished slavery in America.

With Garrison’s life-long goal achieved, the sixty-year-old editor ceased publishing The Liberator, with the final issue dated December 29, 1865.

The praise for the paper’s role in transforming public sentiment on the most controversial issue of the era began immediately. The Nation magazine wrote that The Liberator “has dropped its water upon the nation’s marble heart. Its effect on the moral sentiment of the country was exceedingly great. It went straight to the conscience, and it did more than any one thing beside to create that power of moral conviction which was so indomitable.” Of Garrison’s commitment to the Abolition Movement, The Nation said, “It is, perhaps, the most remarkable instance on record of single-hearted devotion to a cause.” The New York Tribune, one of the progressive newspapers that had joined the abolition cause twenty years after The Liberator had led the way, also praised Garrison’s journalistic triumph. “We lead such aimless and unlovely lives, so void of earnestness and daily beauty,” the paper said. “But now and then comes a man like Mr. Garrison to show us our mistake; to prove what virtue there is in fidelity to a single labor; to accomplish some great work vital to the progress of man.”18

Officials at the highest level of government joined in lionizing Garrison. Secretary of War Edwin Stanton invited him to Washington for a private interview. U.S. Senators Charles Sumner and Henry Wilson ushered Garrison to a place of honor on the floor of the Senate. President Abraham Lincoln wrote a letter of appreciation to Garrison, signaling his respect for the editor by signing the message, “Your friend and servant.” And in the ultimate statement of honor, President Lincoln twice invited Garrison to the White House for sessions in which the two men talked privately.19

In recognition of Garrison’s contribution to abolishing slavery, he was invited to Charleston for a great jubilee. The climax of the day came when a throng of liberated slaves hoisted Garrison triumphantly onto their shoulders and carried him to a platform, surrounded by thousands of African American women and men who understood what he had done for them. Black orator and activist Frederick Douglass spoke for the multitude, calling Garrison “the man to whom more than any other in this Republic we are indebted for the triumph we are celebrating today.”20

STRATEGY OF AGITATION

One of the most intriguing questions related to The Liberator is how a publication of decidedly limited circulation—and with most of the 2,500 subscribers being free northern blacks of scant political or economic power—became such an influential force on one of the most important social movements in American history.

The answer involves Garrison’s masterful skill as a provocateur. He designed a calculated and remarkably modern strategy of agitation to ensure that the sentiments he expressed in his newspaper did not lie sedately on the page to be ignored and forgotten. Instead, he saw to it that his printed words commanded massive public attention and successfully provoked discussion as well as action. Since Garrison’s death in 1879, some historians have glorified him as the moral conscience of the nation while others have vilified him as a nettlesome egotist, but admirers as well as detractors have paid tribute to the editor as a dissident journalist without peer. Gilbert H. Barnes, one of the harshest of Garrison’s scholarly critics, wrote, “As a journalist he was brilliant and provocative.”21

The most sustained technique Garrison employed to boost The Liberator’s rapid ascent into the national spotlight began in January 1831. He exchanged copies of that premier issue with newspapers being published by some 100 other editors—most of them, like most Americans at the time, adamant defenders of slavery. The editors who received Garrison’s Liberator were so offended by his words that they quoted him at length, accompanied by their own statements of outrage, to inform their readers of the extreme nature of the abolitionist credo.22

When Garrison received his copy of a paper in which an editor had berated him, he celebrated. For Garrison then reprinted the editorial attack, along with his own vehement rebuttal. So by the end of this carefully orchestrated editorial chain reaction, Garrison had not only provided his own subscribers with a double dose of lively reading, but he also had introduced readers of a pro-slavery paper to The Liberator and the anti-slavery ideology it promulgated.

For instance, after the editor of the Middletown Gazette received and read Garrison’s inaugural editorial salvos against slavery, the Connecticut editor first repeated, word for word, Garrison’s passionate insistence that he would be as harsh as truth and as uncompromising as justice in his battle to ensure that all slaves were freed. The Gazette editor then added contemptuously: “Mr. Garrison can do no good, either to the cause of humanity or to the slaves, by his violent and intemperate attacks on the slaveholders. That mawkish sentimentality which weeps over imaginary suffering, is proper to be indulged by boarding school misses and antiquated spinsters; but men, grown up men, ought to be ashamed of it.” In the next issue of The Liberator, Garrison reprinted his original words plus the Gazette’s harsh ones, and then he used typography to ridicule the pro-slavery newspaper’s suggestion that slavery did not cause pain, repeating the phrase in disbelief: “IMAGINARY suffering!!” Garrison then denounced the Gazette for having betrayed the progressive nature of the region of the country that it and The Liberator shared, “Such sentiments, if emanating from the south, would excite no surprise; but being those of New-England men, they fill us with disgust.”23

Consequently, within a matter of weeks after Garrison had founded his dissident newspaper, he was engaged in high-pitched verbal combat with dozens of editors in far-flung sections of the country. These battles continued throughout the long life of The Liberator as Garrison argued with pro-slavery editors in states as far south as Georgia and Mississippi and as far west as Ohio and Michigan—all the while building his paper’s reputation across that same vast geographic spread.24

A second technique Garrison used to bring attention to his newspaper, as well as himself and his cause, involved broadening his crusade to end slavery into a crusade to protect the civil liberties of the American citizenry writ large.

Garrison began this expansion in 1837 after hearing that the editor of an abolitionist newspaper in Alton, Illinois, had been killed by a pro-slavery mob. The Rev. Elijah P. Lovejoy was from a prominent New England family and had earned his divinity degree from the prestigious Princeton Theological Seminary; the tragedy of his death at age thirty-five and leaving a wife and young child was compounded by the failure of law enforcement officials to arrest anyone for the murder. The astute Garrison immediately recognized that Rev. Lovejoy’s death and the circumstances surrounding it, if packaged properly, could propel the Abolition Movement in an exciting new direction.25

So in an emotional editorial outlined in a heavy black border, Garrison shrewdly exploited the murder of “a representative of Justice, Liberty and Christianity” to condemn the United States as a nation “diseased beyond recovery.” Garrison maintained the passionate tone of his editorial by swearing that Rev. Lovejoy’s death would serve his crusade against slavery as well as his defense of a free press. “In destroying his press, the enemies of freedom have compelled a thousand to speak out in its stead,” Garrison raged. “In attempting to gag his lips, they have unloosed the tongues of tens of thousands of indignant souls. They have stirred up a national commotion which causes the foundations of the republic to tremble. O most insane and wicked of mankind!”26

Through the highly charged campaign that Garrison launched with that editorial and maintained with numerous others—his sensational headlines included “Horrid Outrage!” and “Lovejoy Murdered!!!”—during the months that followed, he succeeded in transforming the relatively narrow issue of attempting to win freedom for a disenfranchised racial minority into the much broader crusade of defending the civil liberties of all Americans—white as well as black, free as well as oppressed.27

Garrison’s editorials sent shockwaves through the nation, igniting a tide of indignation, resentment, and anger that spread like wildfire. Within a matter of weeks, hosts of people across the country had adopted The Liberator’s interpretation of Rev. Lovejoy’s death. Hundreds of ministers who eulogized the martyred clergyman from their pulpits mentioned Garrison’s paper, and thousands of the men and women who organized public protests supporting free expression and civil liberties also suddenly were talking about the brave journalistic defender of the principles on which America had been founded. As the throngs of patriots previously indifferent to the issue of slavery realized for the first time that their own rights might be imperiled, local anti-slavery societies burst into existence and new members flocked into the national network that was suddenly infused with new life and energy. And the unparalleled surge all could be traced back to Garrison’s finely crafted editorials in support of a free press.28

A third creative technique Garrison originated to keep his dissident publication securely positioned in the nation’s consciousness involved his staging of what today would be labeled “media events”—activities designed to capture the imagination of the American public.

The most shocking of the public exhibitions that Garrison orchestrated came on the Fourth of July in 1854 during what he had billed in advance as a “religious rite.” Henry David Thoreau first addressed those gathered in the picnic grove in Framingham, Massachusetts, but on this day Garrison would upstage even one of America’s most celebrated literary and intellectual giants. The dissident editor first read several passages from the Bible. Then he spoke to the crowd in the slow and steady tones that a minister might use to prepare his congregation for the taking of the sacrament. Telling his listeners that he would now perform an act that would be the testimony of his soul, he lit a candle on the table before him, and, picking up a copy of the Fugitive Slave Law, touched a corner of it to the flame and held it aloft, intoning the words, “And let the people say, Amen.” The crowd dutifully echoed his “Amen.” Finally, Garrison proceeded to undertake the single most sensational gesture of his life. Grasping a copy of the Constitution and lifting it high above his head so everyone in the crowd could see it, he cursed the document as “the source and parent of all the other atrocities, a covenant with death and an agreement with hell.” Garrison then—during this patriotic observance—set fire to the document that, more than any other, symbolized the democratic form of government. As the Constitution burst into flames, the radical editor defiantly declared, “So perish all compromises with tyranny! And let all the people say, Amen!” A few hisses and protests from members of the crowd were eclipsed by a tremendous shout: “Amen!”29

Garrison’s multi-pronged strategy to ensure that The Liberator attracted massive public attention—his exchanges with pro-slavery editors, his expansion of the cause of abolition to a campaign to preserve all civil liberties, and his staging of attention-grabbing media events—was a spectacular success. The various techniques garnered exactly what the provocateur had hoped: spirited discussions of both his paper and the Abolition Movement in kitchens and public meeting places in large cities and small town across the country.

The discussions extended into newsrooms—and onto newspaper front pages from coast to coast. Garrison firmly believed that the American people, North and South, would embrace the anti-slavery cause if they were fully informed about the evils of the “peculiar institution,” and, thanks to the dissident editor’s strategy, the mainstream press accommodated with extensive news coverage of The Liberator and the abolition ideology.

Although the coverage was largely negative, it succeeded in shining the public spotlight onto the Abolition Movement as never before. Typical was a story spread over three columns on page one of the pro-slavery New York Herald, one of the country’s largest and most influential papers. The article, which reported on an anti-slavery meeting where Garrison had spoken, contained denigrating references to the editor’s “bald head, miserable forehead, and comical spectacles” and was even more disparaging to the African Americans who attended the meeting, describing them as “thick-lipped, pig-faced, woolly-headed, baboon-looking negroes.” The article lambasted the meeting as well, saying, “It was one of the most amusing, lamentable, laughable, ridiculous, disgusting and jumbled up affairs that we have had for some time.”30

In addition to these outrageous insults, however, the article also contained highlights from Garrison’s speech—including arguments that were central to the Abolition Movement. Right there on the front page of one of the premier newspapers in the country were words that the abolitionists gladly would have paid a princely sum—if they could have afforded it—to have published so prominently. “If the cause of abolition fails, the world will fall to ruin,” Garrison was quoted as saying. “Our fathers spared nothing to free the country from British yoke, and the freedom of the black slaves is as holy a cause as that of the Revolution!” Another quotation could have come straight from an anti-slavery recruiting brochure: “The abolition army is increasing all over the world; our banner streams on every hill; we are marshalling on every plain by thousands and tens of thousands.” The story—it measured thirty column inches—also reproduced the dramatic jeremiad with which Garrison had ended his rousing speech: “Everyone who is not an abolitionist—no matter how many prayers he says daily; no matter how many church ceremonies he goes through, he is a liar and a hypocrite. He is an enemy to all mankind, and a disgrace to the nation!”31

The Herald was among a legion of mainstream papers—including the most important shapers of public opinion in the country—that provided extensive coverage of Garrison, his dissident newspaper, and the Abolition Movement. Within a matter of months after Garrison had begun publishing, the National Intelligencer in Washington, D.C., reported that The Liberator was being distributed “in great numbers”—a flattering statement, though incorrect—and that the atrocities that slaves had to endure “have already caused the plains of the South to be manured with human flesh and blood.” Other major dailies followed suit. After a crowd of slavery supporters disrupted an anti-slavery meeting, the Philadelphia Ledger adopted Garrison’s concept of civil liberties and editorialized: “It was not an offense against the abolitionists that the mob committed when they broke up Garrison’s meeting, but an offense against the Constitution, against the Union, against the people, against popular rights, and the great cause of human freedom.” The Boston Courier continued to disagree with Garrison on the slavery issue, and yet it praised him as a man of principle and tenacity: “We never read a speech or an article of Mr. Garrison’s without a consciousness of the power which his deep and fervid convictions give him.” By 1854, the New York Times was even printing verbatim transcripts of Garrison’s speeches; so the publication that was well on its way to becoming the nation’s newspaper of record was allowing Garrison to state, boldly and without denunciation: “I am an abolitionist. Hence, I cannot but regard oppression in every form—and most of all, that which turns a man into a thing—with indignation and abhorrence.” Garrison’s speech was spread over five full columns of the Times, building to the crescendo: “Living or dying, defeated or victorious, be it ours to exclaim, ‘No compromise with Slavery! Liberty for all, and forever!’” 32

AROUSING THE NATIONAL CONSCIOUSNESS

The Liberator did not single-handedly bring slavery to an end, but there is no question that the constant and often compelling drumbeat coming from the pages of a widely known and widely talked about abolitionist newspaper week after week, month after month, year after year for three and a half decades helped turn the American consciousness against the sins of slavery. As The Nation asserted in its celebration of The Liberator’s achievements: “Its effect on the moral sentiment of the country was exceedingly great. It went straight to the conscience … to create that power of moral conviction which was so indomitable.” The Nation’s comments about William Lloyd Garrison’s accomplishments are worth repeating as well: “It is, perhaps, the most remarkable instance on record of single-hearted devotion to a cause.”33

Between 1831 and 1865, this radical Boston newspaper led the abolitionist press, as well as the Abolition Movement, in successfully articulating the moral indictment of slavery that precipitated the Civil War and that ultimately forced the institution of slavery into a dark corner of American history. In so doing, The Liberator also set a singular standard that would be difficult for the publications that followed it to match. Along with that challenge, however, The Liberator also gave future generations of dissident journals an example of an editorial commitment combined with a strategy for gaining public notice that together had defined a stunning success.