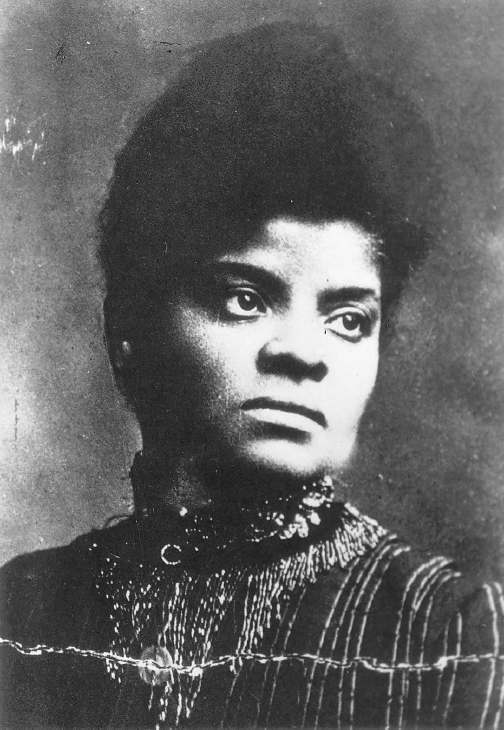

At the age of thirty, Ida Bell Wells—called the “Black Joan of Arc”—launched the anti-lynching press in America. (Reprinted from Alfreda M. Duster, Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells [Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970])

With the collapse of Reconstruction and the departure of federal troops from the former Confederacy, the defeated and demoralized South devised a new means, beginning in the 1870s, to maintain economic and political control over former slaves.

Lynching black men had the short-term purpose of terrifying and intimidating former slaves so they would remain docile and the long-term purpose of perpetuating the feudal system that reigned throughout the South. To rationalize the barbaric act, southern racists contrived the black man’s mythical lust for the white woman. During the final two decades of the nineteenth century, lynching claimed the lives of at least 3,000 African American men. Many of the victims were not only hanged but also riddled with bullets, mutilated, castrated, and burned.1

Most mainstream newspapers, especially in the South, fully supported—even applauded—lynching as a necessary means of controlling blacks, who were portrayed in news stories as uncivilized and dangerous. When eighty white men in DeSoto, Louisiana, hanged Reeves Smith in 1886 after he was accused of, though never tried for, entering the bedroom of a white woman, the New Orleans Daily Picayune characterized the mob as “composed of the best people in the parish.” The Picayune went on to “commend” the lynchers as civic-minded men who clearly had the well-being of their community in mind when they lynched Reeves. “As we have said before,” the city’s largest paper stated, “all such monsters should be disposed of in a summary manner.”2

The first full-scale crusade against lynching came in the form of a social movement launched by a fiercely militant African American woman journalist. In 1892, Ida B. Wells told the readers of the Memphis newspaper she edited, aptly titled the Free Speech, that they should abandon a community that killed innocent men. A few months later, the sharp-tongued Wells dared to challenge the myth that the lynch mobs were hiding behind, stating point blank that some white women willingly engaged in sexual relations with black men. “Nobody in this section of the country believes the old thread-bare lie that Negro men rape white women,” Wells wrote. “If southern white men are not careful, they will over-reach themselves, and public sentiment will have a reaction and a conclusion will be reached which will be very damaging to the moral reputation of their women.”3

With those provocative words, the thirty-year-old Wells launched the Anti-Lynching Movement in this country, unleashing such outrage among southern manhood that she was forced to abandon Memphis and live in exile in the North. Death threats kept Wells from returning to her home, but they did not silence her. Indeed, her banishment imbued Wells with a sense of prophetic mission that propelled her to create a dissident journalistic campaign to arouse the conscience of all of America—and England as well—to the brutalities previously only whispered about in the rural South.4

EARLY CHALLENGES

Born into slavery in 1862 in Holly Springs, Mississippi, Ida Bell Wells was the oldest of eight children in a family headed by Jim Wells, a carpenter, and Lizzie Wells, a cook. Ida’s life was turned upside down in 1878 when a yellow fever epidemic killed her parents and one of her brothers. Refusing to allow her siblings to be separated, the sixteen-year-old young woman assumed full responsibility for the family. Having already completed high school, she piled her hair on top of her head so she would look older and secured a teaching job in a rural school nearby.5

Wells began her life of activism during a train ride in 1884. After purchasing a first-class ticket, Wells sat in the ladies car among white women until a conductor told her that blacks were allowed only in the smoking car. When Wells refused to move and the conductor tried to force the petite woman from her seat, she bit his hand. Three men finally dragged Wells from the car, as white passengers stood on their seats and applauded. After the incident, Wells sued the Chesapeake & Ohio Railroad. The circuit court ruled in her favor and awarded her $500 in damages. Although the Tennessee Supreme Court later reversed the ruling, she nevertheless had established a reputation as an uncompromising woman who was willing to fight an unjust system, regardless of the odds against her.

When the mainstream press failed to report the train ride incident to her liking, Wells entered the world of journalism, in 1885, and told the story herself. About the same time, Wells moved to the larger city of Memphis to a higher-paying teaching job. She then balanced full-time teaching with part-time newspaper writing, selling articles to numerous African American newspapers.

At the age of thirty, Ida Bell Wells—called the “Black Joan of Arc”—launched the anti-lynching press in America. (Reprinted from Alfreda M. Duster, Crusade for Justice: The Autobiography of Ida B. Wells [Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1970])

Wells received effusive praise from T. Thomas Fortune, editor of the New York Age and dean of black journalism. After meeting the diminutive Wells, Fortune told his readers she was “girlish looking in physique” and “as smart as a steel trap.” He also paid Wells a compliment that few American women—black or white—had ever heard before: “She handles a goose quill with a diamond point as handily as any of us men in newspaper work.” Wells was soon dubbed, partly because of her beauty, the “Princess of the Black Press.”6

RAISING A MILITANT VOICE

In 1889, Wells bought one-third interest in the Memphis Free Speech, a Baptist weekly. Her two male partners became business manager and sales manager, while Wells raised a militant editorial voice. Two years later, Wells criticized the city school system she worked for, saying the conditions in the black schools were disgraceful; after her article appeared, she was summarily fired from her teaching job.

Then Wells became a full-time editor with her livelihood depending on the circulation of the Free Speech. She traveled by herself through Mississippi, Tennessee, and Arkansas to secure new subscribers. A taste of Wells’s ingenuity came when she learned that white news dealers, realizing that many illiterate blacks were buying the Free Speech to pass it on to literate friends who would read it aloud to them, were selling copies of white newspapers to blacks who asked for Wells’s paper. So to prevent illiterate blacks from being duped, Wells began printing the Free Speech on pink paper. In less than a year, the circulation of her weekly jumped from 1,500 to 3,500 and became, for the first time, financially profitable.7

Although no copies of the Free Speech have survived, Wells’s articles reprinted in other newspapers paint a portrait of a hard-hitting journalist. In one editorial, she lambasted African Americans who took advantage of others of their race to gain favor with whites, condemning them as “good niggers.” In another, she responded to blacks being sent to prison for stealing five cents while whites thrived after absconding with thousands of dollars by saying of the black thief: “Let him steal big.”8

FOUNDING A MOVEMENT

By 1891, Wells had transformed the Free Speech into a ferociously anti-lynching newspaper. In a typical article, she praised African Americans in Georgetown, Kentucky, who had protested the lynching of a local man by burning down every white-owned building in town. Calling their action a “true spark of manhood,” Wells wrote: “So long as we permit ourselves to be trampled upon, so long we will have to endure it. Not until the Negro rises in his might and takes a hand in resenting such cold-blooded murders, if he has to burn up whole towns, will a halt be called in wholesale lynching.”9

The signal event in Wells’s personal experience with lynching exploded in the spring of 1892. Three of the editor’s friends—she was godmother for the daughter of one of them—had established a grocery store in an African American section of Memphis. When the men’s success jeopardized a white grocer’s economic security, he began harassing his black business rivals. Events escalated to the point that the white grocer and twelve supporters, all armed, entered the back door of the black store and threatened to kill the customers and storekeepers alike. When the African American men fired toward the intruders, a mob of white men killed the three black grocers.

Wells denounced the crime, saying that Memphis was not a fit place for African Americans to live. “There is only one thing left that we can do; leave a town which will neither protect our lives and property, nor give us a fair trial in the courts, but takes us out and murders us in cold blood.”10

Heeding the editor’s call, some 2,000 Americans of African descent abandoned Memphis, severely damaging the local economy. The campaign was so successful, in fact, that the city’s leading white businessmen pleaded with Wells to stop writing her editorials. She refused.11

Indeed, Wells was only warming up. Adopting the techniques of modern-day investigative journalism, she began examining the circumstances surrounding individual lynchings. Although she often was the only black person at the scene after a hanging, her risky pursuit—she carried a loaded pistol in her purse—paid off when she made a shocking discovery: Every case she scrutinized involved a white woman who had willingly become sexually intimate with a black man. It was only later, when the white woman’s attraction for the black man became known and she grew desperate to protect her reputation, Wells discovered, that the woman had accused her African American lover of rape.

Wells then wrote the most incendiary editorial of her life, as she asserted that white women were often attracted to black men. “There are many white women in the South who would marry colored men if such an act would not place them beyond the pale of society,” she defiantly stated. “White men lynch the offending Afro-American, not because he is a despoiler of virtue, but because he succumbs to the smiles of white women.”12

The idea that white women of the Victorian Era might feel such a taboo sexual desire drove the white men of Memphis to hysteria. The city’s mainstream press demanded that the “scurrilous” writer of the editorial either be lynched or branded with a hot iron and castrated—the paper assumed the writer was a man. Wells was at a church convention in Philadelphia when a mob destroyed her press and newspaper office, threatening to kill her and cause mass bloodshed if she returned to Memphis.13

GOING INTO EXILE

Although Wells’s editorial drew hatred from white editors, T. Thomas Fortune admired her courage. He invited Wells to move to the North and write for his New York Age, giving her one-fourth interest in the nationally circulated African American paper, in exchange for her subscription list for the Free Speech.14

After joining the staff of the Age, Wells set out to awaken black readers throughout the United States to the reality of the lynchings that were taking place in the South. Wells turned the Age’s front page into the closest thing America had to an official record of the chilling acts of racial abuse, filling the paper with the details surrounding dozens of lynchings she had investigated first hand.

Her inaugural story in the Age, which covered the entire front page, described the events in Memphis and denounced the rape myth. Fortune touted the blockbuster as the “first inside story of Negro lynching” and sold 10,000 copies, far more than any other single publication in the seventy-five-year history of the African American press. “It created a veritable sensation,” Fortune later said of the article, “and was referred to and discussed in hundreds of newspapers and thousands of homes. It was a historic document, full of the pathos of awful truth.”15

The huge article told, for example, of a black man in Tuscumbia, Alabama, who was lynched even though the white woman he supposedly had raped had publicly stated that she and the man had been involved in a consensual sexual relationship of long duration. Wells also accused the white press in Indianola, Mississippi, of incorrectly stating that a black man had been lynched because he had raped the sheriff’s eight-year-old daughter when, in reality, the girl was in her twenties and had gone to the man’s room of her own free will.16

Knowing that northern readers unfamiliar with the abuses routinely taking place in the South would question the veracity of her reports, Wells not only named names but also blended concrete details and direct quotations into her stories to add to their credibility. Her item about the lynching of Ebenezer Fowler identified him as “the wealthiest colored man in Issaquena County, Miss.,” and reported that the “armed body of white men who filled his body with bullets” was composed entirely of local merchants whose incomes had declined because of Fowler’s superior business acumen.17

Wells made her account of another case come alive by directly quoting the woman involved. The African American man, William Offett, had been convicted of raping the wife of a white minister, even though the woman had testified that Offett came to her home at her request. Wells quoted Mrs. J. S. Underwood as saying: “I invited him to call on me. He called, bringing chestnuts and candy for the children. By this means we got them to leave us alone in the room. Then I sat on his lap. He made a proposal to me and I readily consented. He visited me several times after that. I had no desire to resist.”18

Like other dissident journalists before and after her, Wells was not satisfied merely to report the injustices but also wrote searing editorials against the South, saying: “Her white citizens are wedded to any method, however revolting, for the subjugation of the young manhood of the race. They have cheated him out of his ballot, deprived him of civil rights or redress in the civil courts, robbed him of the fruits of his labor, and are still murdering, burning and lynching him.” Accusing black men of raping white women was “merely an excuse to get rid of Negroes who were acquiring wealth and property,” Wells wrote, “and thus keep the race terrorized and ‘keep the nigger down.’” 19

As for how the violence could be ended, Wells’s first proposal was the same one that she had recommended, and that had succeeded, in Memphis: economic reprisals. Specifically, Wells urged her readers to boycott any white businessman who condoned lynching. “The white man’s dollar is his god,” she wrote bitterly. “The appeal to the white man’s pocket has ever been more effectual than all the appeals ever made to his conscience.”20

Her second proposal was that oppressed African Americans demand that the nation’s newspapers write editorials condemning lynching as barbaric. “The strong arm of the law must be brought to bear upon lynchers in severe punishment, but this cannot and will not be done unless a healthy public sentiment demands and sustains such action,” she wrote. “The people must know before they can act, and there is no educator to compare with the press.”21

Wells’s third—and most controversial—proposal was one that militant leaders of her race would continue to make for generations to come: African Americans had to defend themselves against violence. “Of the many inhuman outrages of this present year, the only case where the proposed lynching did not occur was where the men armed themselves in Jacksonville, Fla., and prevented it. The only times an Afro-American who was assaulted got away has been when he had a gun and used it in self-defense.”22

Wells followed this observation with one of the most radical statements that any African American leader of the nineteenth century would ever make: “A Winchester rifle should have a place of honor in every black home.” She went on to justify her bold proposal by saying: “When the white man knows he runs a risk of biting the dust every time his Afro-American victim does, he will have greater respect for Afro-American life. The more the Afro-American yields and cringes and begs, the more he is insulted, outraged and lynched.”23

EXPANDING THE CRUSADE

Although Wells criticized White America, she soon came to realize that the success of her movement depended on her ability to win the hearts and minds of white northerners to the anti-lynching cause, as they dominated all of the nation’s political, social, and legal institutions. That the target audience for Wells’s writing crossed the color line became clear late in 1892 when she expanded her dissident press crusade beyond African American newspapers to create her first publication that was marketed to whites as well as blacks.

Using the high sales volume of her debut article in the New York Age as a selling point, Wells persuaded T. Thomas Fortune to finance the reprinting of the best of her anti-lynching writing in a pamphlet titled “Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.” Fortune knew that white readers, in particular, would be curious to get a look at the comely African American spitfire who was defying the nation’s pro-lynching establishment, so he hired an artist to fashion a flattering line drawing of his protégé that he placed on the cover of the pamphlet. Fortune then distributed copies of “Southern Horrors” to bookstores in both white and black shopping districts of numerous northern cities.

Wells did her part to promote sales by devoting several of the pamphlet’s twenty-five pages to the contentious topic—then as well as now—of interracial marriage. “The miscegenation laws of the South only operate against the legitimate union of the races,” she wrote, thereby challenging the long-standing legal ban against black/white couples. “Many white women in the South would marry colored men if such an act would not place them within the clutches of the law.”24

Adding to the prestige of “Southern Horrors” was a letter of support from Frederick Douglass, the most respected African American leader of the nineteenth century, that Wells reprinted in the pamphlet. In the letter, Douglass admitted that he had accepted the rape myth until Wells had challenged it. “Let me give you thanks for your faithful work on the lynch abomination,” Douglass wrote in the letter. “There has been no work equal to it in convincing power. I have spoken, but my word is feeble in comparison.” Douglass ended his letter with words of exuberant praise for the anti-lynching pioneer: “Brave woman! You have done your people and mine a service which can neither be weighed nor measured.”25

Similar words of support appeared in leading African American newspapers across the country. “Before the advent of Miss Wells and the consequent Anti-Lynching Movement,” the Indianapolis Freeman wrote, “the Negro’s case in equity had lingered comparatively unnoticed for years.” The Chicago Defender expressed the same sentiment, saying: “If we only had a few men with the backbone of Miss Wells, lynching would soon come to a halt.”26

African American women also supported their courageous sister. Some 250 upper-class black women organized a testimonial dinner for Wells at Lyric Hall in New York City. Later described as “the greatest demonstration ever attempted by race women for one of their own number,” the dinner was a spectacle without peer. Wells’s name was spelled out in electric lights across the dais, miniature versions of the Free Speech were used as programs, soul-stirring music was interspersed with uplifting speeches, and $500 was collected and donated to Wells’s crusade. The climax of the event came when Wells gave an emotional account of her experiences while investigating lynchings.27

LECTURING FOR THE CAUSE AT HOME AND ABROAD

Wells’s speech at that testimonial dinner launched her career as an orator. For the sympathy aroused by her heartfelt words and delivery were the catalyst for her, in 1893, to begin lecturing against lynching throughout the North.

Wells spoke to as many white audiences as she could and also made personal appeals to the editors of mainstream newspapers in the dozens of cities she visited. “A factual appeal to Christian conscience,” she said in a typical speech, “will ultimately stop these crimes.”28

After hearing one of her presentations, the editor of a British newspaper offered to sponsor Wells on a lecture tour in England. The politically savvy Wells eagerly accepted, knowing that Great Britain’s role as the world’s biggest importer of cotton gave English views considerable weight in the American South.

And, indeed, Wells’s overseas tour advanced her campaign enormously. By the time she returned to the United States, the British Anti-Lynching Committee had been formed to oppose lynching in the American South, with its membership including such notables as the Duke of Argyll (Queen Victoria’s son-in-law), the Archbishop of Canterbury, members of Parliament, and the editors of the Manchester Guardian.29

Wells’s rising influence because of her English speaking tour—some people were now calling her the “Black Joan of Arc”—had direct impact on the Anti-Lynching Movement. The effect was particularly dramatic in Memphis, which exported more cotton than any other city in the world. When Wells gave British business and political leaders first-hand accounts of lynchings that had taken place in Memphis, she did serious damage to the image of her former home town. So, as a direct result of her efforts, the city fathers were forced to take an official stand against lynching, and for the next twenty years there was not another incident of vigilante violence there.30

In addition, numerous articles about Wells, her lectures, and the Anti-Lynching Movement had now begun to appear in such mainstream publications as the Literary Digest, Atlanta Constitution, Washington (D.C.) City Post, and New York Sun. Although the articles were uniformly critical of Wells—the New York Times denounced her as a “slanderous and nasty-minded mulatress” and a fraud: “She knows nothing about the colored problem in the South. A reputable or respectable negro has never been lynched, and never will be”—they nevertheless increased her visibility and communicated her message to White America.31

And, on rare occasion, the mainstream press even began to publish words of support for the Anti-Lynching Movement that Wells had founded. After Wells supplied the Chicago Inter-Ocean with documentation showing that the white woman a black man named Ed Coy allegedly had raped had, in fact, seduced the man, the white paper published an article supporting Wells’s conclusion: “The woman was a willing partner in the victim’s guilt.” After that initial breakthrough, Wells persuaded the paper’s editor to publish other supportive articles. “The real need is for a public sentiment in favor of enforcing the law and giving every man, white and black, a fair hearing before the lawful tribunals,” the Inter-Ocean argued in the summer of 1893. “The Negro has as good a right to a fair trial as the white man.”32

Wells’s trip to England was such a triumph that she was invited back for another speaking tour in 1894. This time, she presented more than 100 lectures, was honored at a breakfast with members of Parliament, and wrote a weekly column titled “Ida B. Wells Abroad” for the Inter-Ocean—marking the first time the paper had ever published the work of an African American writer.33

Wells maintained the intensity of her crusade. She devoted an entire year to lecturing and organizing a network of local and statewide anti-lynching societies from New England to California, focusing in particular on white audiences. Her mantra during her presentations became: “It is the white people of this country who have to mold the public sentiment necessary to put a stop to lynching.”34

It was also in 1894 that Wells entered the rough-and-tumble of political lobbying. Within a month after returning from her second triumphant British speaking tour, she persuaded Congressman Henry Blair of New Hampshire to introduce federal legislation calling for an investigation of all acts of mob violence committed as punitive measures—“by whipping, lynching, or otherwise”—against alleged criminals. Blair presented his fellow members of Congress with petitions from citizens of twelve states—Wells had collected a good portion of the names during her lecture tour. Blair’s proposal eventually died in committee, but it marked the first time that the travesty of lynching had been debated in the U.S. Congress.35

Wells’s lobbying efforts were far more effective on the state level. Between 1893 and 1897, she helped persuade the legislatures in five southern states to enact their first anti-lynching laws. The measures established penalties against sheriffs who failed to protect accused persons from mob violence and against private citizens who broke into jails or otherwise obstructed the legal process.36

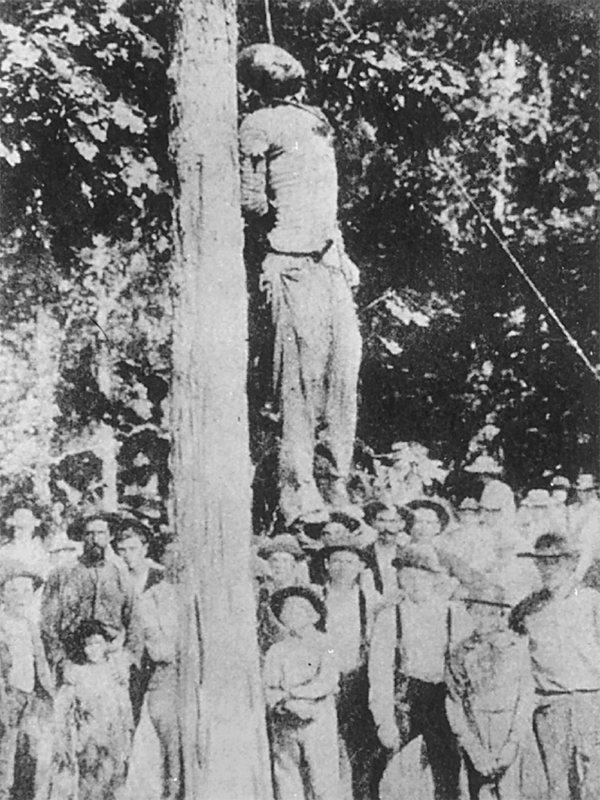

Early in 1895, Wells began distributing another pamphlet, this one providing the nation’s first comprehensive history of lynching, “A Red Record: Tabulated Statistics and Alleged Causes of Lynching in the United States.” The most memorable single element of the 100-page work was one of the most haunting images ever printed in an American publication. The photo, taken at an Alabama lynching in 1891, showed a black victim hanging lifeless from a tree—his neck broken to the point that it was almost at a right angle to his head. Surrounding the dead man was a crowd of white men and boys posing proudly for the traveling photographer who had captured the moment, eager to show their unflagging support for law and order as practiced in the American South.37

The pamphlet listed the names, dates, locations, and charges for all of the lynchings that had taken place during the previous year, while also noting the progress of the Anti-Lynching Movement. “There is now an awakened conscience throughout the land,” Wells could justly write, “and Lynch Law can not flourish in the future as it has in the past.” To support her rose-colored assessment, Wells cited Ohio Governor William McKinley calling out the militia in October 1894 to protect a black prisoner from a lynch mob—the man was later found innocent of the charges and released.38

Meanwhile, statistics documented both Wells’s optimism about the decline of lynching and her success as a dissident journalist. For in 1893, the number of lynchings nationwide had decreased for the first time—dropping from 235 to 200.39

The most memorable element in Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s 1895 pamphlet, “A Red Record,” was the haunting image of an 1891 lynching in Alabama. (Reprinted from “A Red Record”)

By the time Wells wrote “A Red Record” in 1895, she no longer needed T. Thomas Fortune’s support as she was an internationally known activist and publishing entrepreneur in her own right. She paid to have the pamphlet printed and distributed to white as well as black bookstores throughout the North and, to the extent possible, the South.

Marketing the hefty booklet also launched the Central Anti-Lynching League, a national information clearing house for Wells’s written work. “Anti-lynching societies and individuals can order copies from the league,” she wrote at the end of the pamphlet. “The writer hereof assures prompt distribution according to order, and public acknowledgment of all orders through the public press.”40

ENTERING A NEW PHASE OF LIFE

By this point, Chicago had become Wells’s home base. She first went to the city in 1893, between her trips abroad, to take her anti-lynching crusade to the throngs of visitors who attended the historic World’s Columbian Exposition.

She collaborated with Frederick Douglass and Ferdinand L. Barnett, editor of the Chicago Conservator, to write and publish an eighty-page pamphlet titled “The Reason Why the Colored American Is Not in the World’s Columbian Exposition.” Her section reproduced some of her anti-lynching writing, and she distributed 20,000 copies of the pamphlet at the fair, while also drawing a sizable crowd to the public lecture she gave at the Haitian Pavilion.41

Soon after arriving in Chicago, Wells began writing anti-lynching articles for the Conservator. Barnett, like Wells, had been born a slave. He went on to earn a law degree from Northwestern University and in 1878 founded the paper as the first African American publishing voice in the city. Tall, handsome, and with courtly manners that made him acceptable to prominent whites, Barnett was a strong advocate for racial equality.

As Wells and Barnett, whose wife had recently died, worked together on various projects, they came to recognize the compatibility of their shared commitments to activism and journalism. They married in July 1895, with the bride reaffirming her life-long independence by adopting a hyphenated last name in one of the earliest instances of that feminist practice.

After the marriage, Ida B. Wells-Barnett became owner and editor of the Chicago Conservator while her husband focused on his new position as the first African American assistant state’s attorney in the city’s history. Barnett had two sons from his first marriage, and, within a year after their wedding, Wells-Barnett embraced motherhood with the same enthusiasm that characterized other aspects of her life. She gave birth to four children—including a daughter named Ida B. Wells Jr.—in eight years.42

Partly out of concern for her two stepsons who already had lost one mother and partly because of how the death of her own parents had disrupted her and her siblings’ youth, Wells-Barnett announced in 1897 that she was relinquishing her position as editor of the Conservator and retiring from public life to devote all her time and energy to her family.

Her “retirement” lasted five months.

Wells-Barnett resumed her activism in response to the brutal lynching of a Lake City, South Carolina, man in 1898. She was outraged by the incident in which the man was hanged and he and his infant son were burned “to a crisp,” according to the Charleston News and Courier, because “the good people of Lake City” were angry that federal officials had appointed the man to the prestigious position of town postmaster. After investigating the events, Wells-Barnett led a citizen delegation to the White House to ask President William McKinley to punish the offenders and, because the victim was a federal employee, to enact a national anti-lynching law. “Nowhere in the civilized world save the United States,” she protested, “do men go out in bands to hunt down, shoot, hang or burn to death a single individual.” McKinley assured Wells-Barnett that he was in “hearty accord” with her concerns and that the appropriate departments would look into the matter, although ultimately nothing came of those promises.43

That lack of action reinforced Wells-Barnett’s adamant belief that White America had to be convinced of the barbarism of lynching. So she renewed her commitment to publishing her dissident words in pamphlets that were aimed at both black and white readers.

In 1900, she published “Mob Rule in New Orleans,” a fifty-page booklet that focused on a series of race riots that erupted in Louisiana. Her detailed account of the tragedy included harsh critiques of the city’s two mainstream dailies, the Picayune and the Times-Democrat. Both papers, Wells-Barnett wrote, routinely used the terms “ruffians,” “fiends,” and “monsters” as synonyms for African American men and consistently encouraged mob violence through statements such as one in the Times-Democrat: “The only way that you can teach these Niggers a lesson and put them in their place is to go out and lynch a few of them as an object lesson. String up a few of them, and the others will trouble you no more.”44

The most far-reaching effort Wells-Barnett was involved in during this period was helping to found the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. She was one of sixty persons, including only one other African American woman, who organized the 1909 gathering where the NAACP was formed.

Wells-Barnett stunned the crowd that had assembled for the historic meeting, as she told her fellow activists: “Agitation, though helpful, will not alone stop the crime of lynching.” Despite her years of activism, she continued, it had become clear to her that the “only certain remedy” was to persuade the country’s political community to designate lynching a federal crime. Wells-Barnett’s speech helped set the course for the NAACP, as the founders accepted her proposal not to be aggressive in their opposition to whites but to include them in the organization’s leadership positions.45

Her position vis-à-vis strategy carried considerable weight because of the success of the Anti-Lynching Movement; by 1909, the number of lynchings reported nationwide had dropped to eighty-seven.46

Throughout the early decades of the twentieth century, Wells-Barnett remained actively involved in dissident journalism through articles she wrote for the Chicago Tribune and several national magazines. Although the articles were aimed at white readers as well as black, the irrepressible activist pulled no punches. In a 1913 piece in Survey magazine, Wells-Barnett protested: “The nation cannot profess Christianity, which makes the golden rule its foundation stone, and continue to deny equal opportunity for life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness to the black race. When our Christian and moral influences not only concede these principles theoretically but work for them practically, lynching will become a thing of the past.”47

Wells-Barnett’s strong words were still very much needed, as many mainstream publications continued to denigrate Americans of African descent. “The Negroes, as a rule, are very ignorant, are very lazy, are very brutal, are very criminal,” the Atlantic Monthly wrote in 1909. “They are creatures of brutal, untamed instincts, and uncontrollable feral passions, which give frequent expression of themselves in crimes of horrible ferocity. They are, in brief, an uncivilized and semi-savage people.”48

The founder of the Anti-Lynching Movement remained committed to changing White America’s perception of her people by uncovering and reporting the truth about the lynchings that continued to plague the country. Although she regretted having to spend time apart from her children, Wells-Barnett could not turn down the standing offer from the nation’s leading newspapers and magazines that were eager to publish her compelling investigative articles. So whether the incident had taken place relatively near Chicago, such as in East St. Louis, Illinois, in 1918, or hundreds of miles away, such as in Elaine, Arkansas, in 1922, Wells-Barnett packed her bag—and her pistol—and traveled to the scene to probe the details that had led to the wrongful killing. The journey to Arkansas marked Wells-Barnett’s return to the South for the first time since she had been banished from that section of the country thirty years earlier.49

Although Wells-Barnett went to many cities during the first two decades of the twentieth century, her most frequent destination was Washington, D.C., where she became a familiar presence in the halls of Congress. Some sixteen anti-lynching bills were introduced in committees of the Senate or the House of Representatives during those years, each one seeking to establish lynching as a federal crime. And by 1918, some of the proposals were considered with sufficient seriousness that they became the subjects of public hearings—with Wells-Barnett the most inveterate of the witnesses at the sessions.50

A major breakthrough finally came in 1922 when a federal anti-lynching bill moved out of committee and onto the House floor. Missouri Congressman Leonidas Dyer introduced the legislation, and hard lobbying by Wells-Barnett and other leaders of the NAACP succeeded in getting the bill passed in the lower house. Despite visits to the offices of dozens of senators, Wells-Barnett—by then sixty years old—had to stand by helpless and watch as a powerful southern filibuster blocked a vote in the Senate. After that disappointing defeat, the NAACP shifted its focus to campaigning for anti-lynching legislation on the state level.51

In sync with this strategy, Wells-Barnett decided, after four decades of relentless lobbying of lawmakers, to seek elected office herself. So in 1930, she campaigned for a seat in the Illinois State Senate, running as an independent. She held dozens of rallies, published hundreds of articles and editorials in the city’s newspapers, and blanketed the city with thousands of flyers, but the outspoken woman received a mere eight percent of the vote.52

Within a year of her first bid for elected office, Ida B. Wells-Barnett contracted a kidney disease. After a brief illness, she died in 1931, at the age of sixty-nine.53

A LIMITED LEGACY

W.E.B. DuBois’s eulogy read: “Ida Wells-Barnett was the pioneer of the anti-lynching crusade in the United States. She began the awakening of the conscience of the nation.” DuBois, the leading African American intellectual of the early twentieth century, was wise to choose the verb began. For in 1892 when the “Princess of the Black Press,” then barely thirty years old, launched her social movement against the barbaric act of lynching, it was, in fact, only the beginning of a long and arduous journey.54

The white overlords who ruled the American South had no intention of abandoning the highly effective technique they had devised, as Wells put it, to “keep the nigger down.” And yet, a single voice of dissidence did begin the slow process of wearing away the bigotry that was underpinning the heinous practice of lynching. After less than a year of challenging conventional thinking regarding black men raping white women, the dissident journalist could rightly claim progress; never again would the South commit as many lynchings as it had in the year that Wells launched her crusade in 1892.55

Other milestones of progress could be attributed to this agent of change as well. The anti-lynching legislation enacted by the various states beginning in 1893 provided several punitive measures. With hidebound law enforcement officials and vigilante citizens being punished for the first time, “Judge Lynch” clearly was on the run.

Journalists and historians alike placed the credit for that progress at the feet of the “Black Joan of Arc.” T. Thomas Fortune, Wells-Barnett’s long-time admirer, wrote, “No history of the Afro-American will be complete in which this woman’s work has not a place.” Others soon added to the chorus of praise. An early scholar of women journalists gushed, “No writer, the male fraternity not excepted, has struck harder blows at the wrongs against the race,” and the first historian of the lynching phenomenon cited Wells-Barnett’s hundreds of newspaper articles and numerous pamphlets—some of them distributed to as many as 20,000 readers—as the single most important catalyst for state legislatures enacting anti-lynching laws.56

And yet it would be an overstatement to assert that either Wells-Barnett or the Anti-Lynching Movement that she founded was successful in eradicating the crime of hanging innocent African American men. No federal law was passed, and southern racists continued their reign of terror via the rope well into the twentieth century. Indeed, it would not be until the year 1953 that, for the first time, not a single lynching occurred anywhere in the United States.57

Despite Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s courage and fortitude, then, her anti-lynching press must be consigned to the category of the dissident press that helped initiate a conversation about a problem but ultimately failed to solve it.