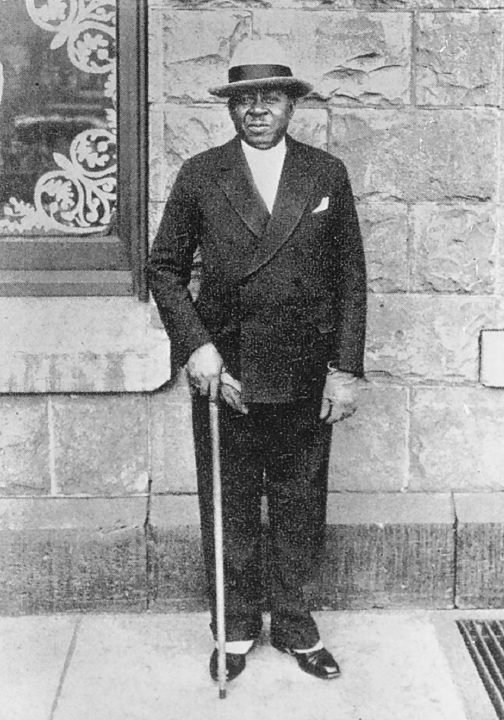

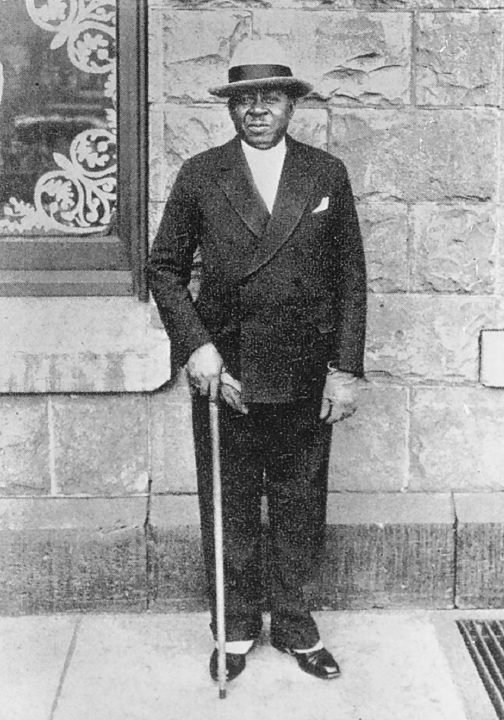

The first African American journalist to become a millionaire, Robert S. Abbott routinely wore double-breasted suits, spats, and gloves, while carrying a walking stick topped with a gold handle. (Courtesy Regnery Publishing Company)

Throughout the nineteenth century and well into the twentieth, the vast majority of black Americans remained second-class citizens. Ninety percent of them lived in the South, prohibited from voting or holding public office and denied political and economic control over their own lives. Most black men and women worked from dawn to dusk as field hands, paid whatever paltry sum their white employers chose to give them. Enduring a virtual feudal system in which even the most basic of human rights did not exist, women and girls were forced into sexual servitude by white overlords who kept black men demoralized and in a constant state of intimidation.

Not until the second decade of the twentieth century did the peonage system that defined the lives of disenfranchised blacks finally begin to fade from the American experience. During World War I, huge numbers of men, women, and children abandoned the oppressive social order in the South to create the first mass migration of African Americans and to take advantage of unprecedented opportunities in the manufacturing centers of the North. The wartime build-up opened new job possibilities to black workers because the global conflict raised the demand for industrial products while simultaneously stemming the flow of European immigrants who in earlier decades had been the major source of the urban workforce. The exodus from the South was so significant that it ultimately rivaled emancipation as a liberating experience, as Americans of African descent came to see the North as nothing less than the storied Promised Land.

The mass movement grew to staggering proportions between 1916 and 1919 as cities, towns, and backwater farming communities below the Mason-Dixon Line watched the throngs of defectors swell larger and larger. During a time when the entire black population of the United States totaled only ten million, the Great Migration saw the number of African Americans moving from the South to the North climb to 500,000.1

The historic demographic shift had major effects on the North as well, with the African American population of New York, Detroit, and Philadelphia mushrooming as never before. But the urban center that drew more southern blacks than any other was Chicago. Various factors contributed to the city’s preeminence as a racial magnet—industrial jobs abounded and the tracks of the Illinois Central Railroad stretched from Tennessee, Mississippi, and Louisiana straight to the terminal in downtown Chicago. But as historians have studied the Great Migration, they have repeatedly identified one more force as key to the city becoming the focal point of this unprecedented mass movement: the Chicago Defender.2

Carl Sandburg was among the many historians who credited the dissident newspaper with sparking the migration, writing, “The Defender, more than any other one agency, was the big cause of the ‘northern fever’ and the big exodus from the South.” A second scholar stated that “Chicago’s image as a northern mecca can be attributed mainly to the Chicago Defender,” and a third wrote, “The Defender became one of the most potent factors in a phenomenal Hegira that began to change the character and pattern of race relations in the United States.”3

Robert S. Abbott, the paper’s founder, also was lauded for his role in the mass movement. One scholar wrote that Abbott “set the migration in motion,” and another crowned Abbott, because he urged blacks to leave the South, “the greatest single force” in the history of black journalism. Though it would be an overstatement to credit Abbott with single-handedly causing the remarkable phenomenon, he clearly was a man of vision who used the means available to him as a newspaper editor to synchronize the northern migration with the flow of history. “We advocate migration,” Abbott said in one of the hundreds of editorials he wrote on the subject. “On account of the war demands, economic conditions in our industrial life afford us an opportunity to better our condition by leaving the South.”4

In the early 1900s, the Chicago Defender was the largest black newspaper in the country, boasting a circulation of 230,000. Of even more importance to the mass movement, the weekly was distributed nationally, with two-thirds of its copies sent outside of Chicago—most of them into the South.5

While these statistics are impressive in their own right, they do not take into account two modes of informal circulation. The Defender was routinely passed among relatives, friends, neighbors, and church members who could not afford the $1.50 a year subscription. As one man wrote, “Copies were passed around until worn out.” In addition, large numbers of illiterate southern blacks gathered in churches and barbershops to hear one person read the paper out loud. Such communal reading was so pervasive that scholars estimate that each copy of the Defender was read by five to seven people. Therefore, during the height of the migration, the number of African Americans reading the paper, or hearing it read aloud, soared well beyond the one million mark.6

In many towns across the South, the Defender’s arrival became a weekly event of major proportion. A Louisiana woman wrote that the paper was “a God sent blessing to the Race” and that she would “rather read it than to eat when Saturday comes,” and another reader marveled that “Negroes grab the Defender like a hungry mule grabs fodder.” In Mississippi, “a man was regarded as ‘intelligent’ if he read the Defender,” and even illiterate men bought the paper “because it was regarded as precious.” In short, the Chicago Defender achieved a mass appeal far beyond anything Black America had ever known. “With the exception of the Bible,” one scholar said, “no publication was more influential among the Negro masses.”7

And the primary message, delivered week after week, was simple and direct: Go North!

RISE OF THE “WORLD’S GREATEST WEEKLY”

Robert Sengstacke Abbott was born in 1868 to former slaves living in rural Georgia. A young man of remarkable will and fortitude, Abbott earned a bachelor’s degree from Hampton Institute in Virginia and a law degree from Kent College in Illinois. His dream of practicing law evaporated, however, when Chicago’s leading African American attorney told Abbott his skin was “a little too dark” to make a positive impression in the country’s white-dominated courtrooms. Abbott vowed that if he could not effect social change through law, he would do so through journalism.8

The Chicago Defender appeared in the spring of 1905. Abbott had no money to pay anyone to help him with the various duties involved in publishing a newspaper, so he became the sole writer, editor, printer, ad salesman, accountant, and newsboy. For the next four years, he struggled to keep the paper afloat, failing to increase his weekly circulation beyond a scant 300 copies.

On the brink of abandoning the newspaper business, Abbott changed his tactics. Instead of filling his pages with the tepid community news—religious items mixed with announcements of local births, weddings, and deaths—that was the staple of black journalism of the era, he began serving up spicier fare. Political cartoons lampooned racist government officials, and shrill editorials denounced black oppression. Most noteworthy of all were the front-page banner headlines, many of them printed in bright red ink and each one larger than the one before—“White Man Rapes Colored Girl,” “Aged Man Is Burned to Death by Whites.” Critics called Abbott’s approach to the news sensationalistic, but circulation and advertising revenue soared.9

The first African American journalist to become a millionaire, Robert S. Abbott routinely wore double-breasted suits, spats, and gloves, while carrying a walking stick topped with a gold handle. (Courtesy Regnery Publishing Company)

Reveling in his success, Abbott—never a modest man—set his sights on creating an African American paper that lived up to the boastful motto he placed at the top of page one: “The World’s Greatest Weekly.” To achieve this lofty ambition, Abbott focused on two goals. First, he had to circulate his paper in the South, the area of the country that was home to the vast majority of African Americans. Second, he had to prove to his readers that the Defender was willing to speak boldly on behalf of Black America.

To expand into the South, Abbott curried the favor of the thousands of black men who worked as sleeping-car porters. He began in 1910 by inaugurating a weekly column called “Railroad Rumblings,” filling it with bits of news and personal items about railroad workers. The editor also vigorously supported the efforts of railroad workers, playing a major role in securing a ten-percent wage hike for them. This strategy was prelude to the brilliant step Abbott took in 1916: He began giving bundles of the hot-off-the-press Defender to black porters just before they left Chicago, asking the men to deliver the papers to newsboys waiting for them in the hundreds of towns and cities the trains passed through as they headed south. It was a circulation-building concept inspired both in its simplicity and its success. During Abbott’s campaign for the mass movement to the North, his paper was distributed not only in large southern cities such as New Orleans—where readers could buy it on city buses or from any of three news dealers who sold 1,000 copies a week—but also in tiny communities from Yoakum, Texas, to Palataka, Florida.10

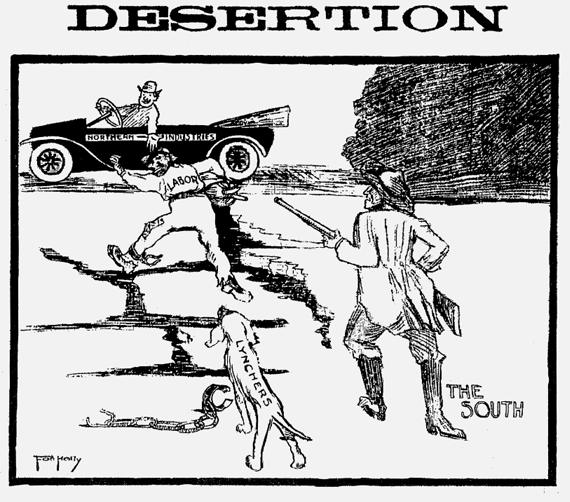

This 1916 Chicago Defender editorial cartoon depicted a terrorized black laborer escaping from the South by racing toward the industrializing North that welcomed him. (Courtesy Chicago Defender)

With regard to showing black readers that the Defender was agitating for them, Abbott refused to cower to White America. After a vigilante mob killed a black man in North Carolina, the editor called for retaliation: “An Eye for an Eye, a Tooth for a Tooth.” Other page-one headlines carried the same rebellious message—“Lynching Must Be Stopped by Shotgun,” “When the Mob Comes and You Must Die, Take at Least One with You,” and “Call the White Fiends to the Door and Shoot them Down.” The Defender’s strident editorial content convinced southern readers not only that the World’s Greatest Weekly truly was the “defender” of the race but that the North must be far freer than the South if an editor was allowed to print such statements—and live to read them.11

VILIFYING THE SOUTH

Although racism was rampant in the South in the early 1900s, most African Americans knew of the widespread abuse only through word of mouth or personal observation because white papers below the Mason-Dixon Line would not report it and southern black papers dared not report it.

Not so the Defender. The outspoken weekly—in a continuation of the model that Ida B. Wells-Barnett had pioneered in her anti-lynching publications of the late 1800s—was committed to documenting the acts of persecution wherever they occurred. So Abbott drafted the army of railroad porters who distributed the Defender to double as correspondents who ensured that an incident that took place anywhere in the South found its way into the paper and, consequently, was reported nationwide.

One front-page article listed dozens of southern towns where any black man who was on the street after 8:30 p.m. was automatically arrested—then beaten. Another item reported that white residents of Clarksville, Tennessee, were so angry when blacks built a church in a middle-class section of the city that they burned the building to the ground. Still another item told Black America that when a white patrolman in Memphis told an African American woman walking on the street to halt but she kept walking, the officer shot her and then left her to bleed to death rather than take her to a hospital, saying she would have gotten blood on the upholstery of his brand new police car.12

In none of these instances was there a single arrest.

Abbott also published uncompromising editorial cartoons. In one drawing, an African American man fleeing from a white man with a gun was running toward a waiting automobile labeled “Northern Industries.” In another, a black man was hanging from a tree while, in the background, a cluster of black men, women, and children marched northward; the cartoon was labeled “The Exodus.”13

Beside many of the drawings appeared fiery editorials spewing forth Abbott’s venom toward the South. One raged that sixteen black men had been lynched in Georgia during the previous month, “a record even for this state of backward civilization where violence triumphs over law.” Abbott ended the piece with a statement and a question: “We have this same hideous story every year. Are we ever going to do anything about it?” In another editorial, the dissident editor insisted, “Anywhere in God’s country is far better than the southland. Come join the ranks of the free. Cast the yoke from around your neck. See the light. When you have crossed the Ohio river, breathe the fresh air and say, ‘Why didn’t I come before?’” 14

More than willing to place blame, Abbott waged rhetorical warfare against southern racists, filling his columns with invective far too dangerous for any black editor to express openly in the South. He routinely called white people “crackers” and referred to white politicians as “pigeon-livered.” In one angry editorial, Abbott labeled white leaders “wage thieves,” “ignorant asses,” and “murderers”; in another, he called southern whites “no-accounts,” “persecutors,” “ravishers of Negro women,” and “killers of Negro men.”15

But more compelling even than the editorial cartoons or the angry oratory were the gruesome details contained in the news stories. For when reporting violence in the South, the Defender spared nothing, adopting a far more sensationalistic tone in its coverage than had Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s publications before it. Indeed, some scholars have suggested that Abbott may even have embellished the stories for maximum effect. Regardless of how much of the final product was reality and how much was the creation of an editor committed to moving his readers to action, the articles were shocking.16

■ A story from Temple, Texas, described how a black man named Will Stanley, while waiting to be tried on a murder charge, “was taken from jail at midnight and burned on the public square in the presence of hundreds of men, women, boys and girls, who cheered as the victim went up in smoke.”17

■ Another estimated that between 15,000 and 20,000 whites in Waco, Texas, watched as eighteen-year-old Jesse Washington, another black man awaiting trial, was tied to a tree and set on fire, “with the horror of flames rising around the flesh of the squirming boy and as tears rolled out of his eyes.” But the crowd was still not satisfied. “After the fire subsided, the mob hacked with pen-knifes the fingers, the toes and pieces of flesh from the body, carrying them as souvenirs to their automobiles.”18

■ From Dyersburg, Tennessee, came the story of the final hours of Lation Scott, a prisoner who was bound to an iron post while men heated pokers and irons until they were “white with heat” and thereby prepared for their dastardly task—boring out the prisoner’s eyes. When this occurred, “Scott moaned,” the Defender reported, before continuing in riveting detail. “The pokers were worked like an auger, that is, they were twisted round and round. The smell of burning flesh permeated the atmosphere, a pungent, sickening odor telling those who failed to get good vantage points what their eyes could not see: Irons were searing the flesh.” Scott was still alive when the townspeople, including women and children, piled wood and rubbish around him and continued to feed the fire until he became “a heap of charred ashes and bones.”19

GLORIFYING THE NORTH

Abbott’s depiction of the appalling realities of life in the South stood in glaring contrast to his exaltations about the benefits of moving to the North. Week after week, the Defender used advertisements, editorials, and news and feature stories to tell readers of the Black American Dream awaiting them at the northern end of the railroad tracks. Abbott even negotiated with the Illinois Central Railroad for reduced fares for groups of ten or more migrants traveling together and printed, free of charge, the train schedule—one way from south to north.

If any single word captured the reason, according to Robert S. Abbott, that African Americans should relocate to the Promised Land, that word was spelled J-O-B-S. The Defender published thousands of employment ads such as: “Wanted—Men for laborers and semi-skilled occupations. Address or apply to the employment department, Westinghouse Electric Co.” Many of the ads specifically mentioned that “Negroes” were urged to apply, and the jobs themselves targeted that same audience, asking for “warehouse workers,” “cement mixers,” and “laborers for steel mill” who did not have to have specific skills, only a willingness to work. The wages in the ads appealed to blacks as well; southern farm workers typically were paid seventy-five cents a day, while northern factory wages started at $4 a day and climbed as high as $10.20

Abbott reinforced the job opportunities through a stream of statements on his editorial page that insisted the integrated employment that blacks had dreamed of for so long had finally arrived—in the North. “The bars are being let down in the industrial world as never before,” he asserted. “We have talked and argued and sat up late at night planning what we would do if we only had an opportunity. Now that it is here, how many are going to grasp it?” The powerful editor often challenged his readers, insisting that it was not only in their best interest individually to take advantage of the new opportunities provided by the wartime build-up but also their duty to the race. “We must fill the new positions offered us; by so doing we will secure a stable position in the world’s work,” Abbott thundered. “Our chance is right now.”21

In addition to glorifying Chicago as offering unlimited jobs, Abbott beat his northern migration drum by portraying his adopted city as a wonderland of leisure-time activities. For a southern black field worker who spent from dawn to dusk looking at the back end of a mule, opening the Defender was comparable to discovering a whole new world.

The film “Trooper of Company K” was “easily the greatest production ever attempted by our people,” the Defender gushed. Complete with an “all colored cast” of 350 and featuring heartthrob Noble Johnson as a military hero, the paper continued, “It depicts in gripping scenes the unflinching bravery of the troopers under fire and how they, greatly outnumbered, sacrificed their blood and life for their country. Interposed in the picture are scenes of romantic love, comedy and human interest. Don’t fail to attend the Washington Theater during the run of this wonderful picture.” Although the paper’s praise of “Trooper” was unrestrained, the film was only one of forty available to African American Chicagoans the first week of October 1916—forty more than were available to blacks living anywhere in the South.22

The Defender’s hefty entertainment section reported that amusement options extended well beyond the silver screen. “Remarkable dramatic actress” Dorothy Donnelly played the lead in the stage play “Madame X” at States Theater, William and Salem Tutt starred in a musical extravaganza at The Grand, the Drake-Walker Players drew packed houses nightly for their musicale at The Monogram, Joe Sheftel and his Black Dots regaled audiences with “real harmony, real dancing, and a riot of fun” at The Orpheum, and Clabrun Jones and his Yama Yama Players, complete with their own orchestra and chorus of fifteen voices, presented a musical review at the New Monogram.23

In the opinion of the Defender’s music critic, though, the best show to hit Black Chicago—“Entertainment Extraordinary!”—was Clarence Jones performing “first class vaudeville” at the “everything up to the minute” Owl Theater—“with 1,200 roomy seats, $10,000 Kimball pipe organ, 8 piece orchestra, and perfect ventilation.”24

The Defender also promoted the cornucopia of activities that African Americans could enjoy during the day. The paper bragged about the city’s well-equipped playgrounds and the open access, regardless of race, to the beaches along Lake Michigan. Sports fans were told of the triumphs of black Chicago’s own boxing champion, Jack Johnson, and were reminded that games between African American baseball teams took place nearly every day and that the Chicago-based American Giants were the greatest black sluggers in the country.25

By 1918, a Mississippi man spoke for thousands of his race when he wrote that, after reading the Defender, he was quite sure that Chicago was nothing short of “heaven itself.”26

CREATING “MIGRATION FEVER”

Abbott did not stop with vilifying the South and glorifying the North but also took it upon himself to engineer what became known as “migration fever.”

The crusading editor believed that southern blacks were more likely to leave their homes if they saw themselves not as isolated migrants but as members of a mass movement. So he methodically communicated to his readers that a widespread exodus was, in fact, taking place. As one scholar put it, Abbott constructed “an atmosphere of hysteria. The more people who left, inspired by Defender propaganda, the more who wanted to go, so the migration fed on itself until in some places it turned into a wild stampede”—all choreographed by the dissident editor.27

Abbott launched his campaign in the fall of 1916 by spreading a photograph across his front page and labeling it, in inch-high capital letters: “THE EXODUS.” The huge image showed the railroad yard in Savannah, Georgia, literally covered with hundreds upon hundreds of African Americans—so many people that the train tracks were barely visible—waiting to board the next north-bound train. The caption told readers: “Men, tired of being kicked and cursed, are leaving by the thousands as the above picture shows.”28

In the months that followed, Abbott raised momentum for migration to a fever pitch by blanketing his pages with dozens of headlines—“Leaving for the North,” “Farewell, Dixie Land,” “300 Leave for North”—and by filling rivers of type with news items crafted to inspire still more departures. From Meridian, Mississippi: “Members of the Race have left for Chicago. They are going where better wages and schooling conditions exist.” From Selma, Alabama: “Over 200 left here on the railroad for the north.” From Talladega, Alabama: “The great exodus has struck Talladega County.” From Summit, Mississippi: “Twenty-four carloads passed through here last week.” From Waycross, Georgia: “There are so many leaving here that Waycross will be desolate soon.” From Aberdeen, Mississippi: “The migration to the north seems to be an epidemic that breaks out every Saturday when the latest Chicago Defender arrives.”29

Abbott eagerly highlighted his paper’s role in propelling African Americans into the Promised Land. “The Defender propaganda to leave the south where they find conditions intolerable is receiving a hearty response,” read one item, while others highlighted the observations of the hundreds of men and women who contributed news items to the proactive paper. One correspondent wrote of seeing 2,000 black men and women gathered at the Memphis train station. “Number 4, due to leave for Chicago at 8:00 o’clock, was held up twenty minutes so that those people who hadn’t purchased tickets might be taken aboard,” the man wrote. “It was necessary to add two additional eighty-foot steel coaches to the Chicago train in order to accommodate the Race people, and at the lowest estimation there were more than 1,200 taken on board.”30

After the migration impulse took hold, one of the ways Abbott kept reader enthusiasm at a high level was by juxtaposing images of the South and the North. A typical pictorial item consisted of two photos, one on top of the other. The lower image, which filled only two columns, was of the Freetown School in Abbeville, Louisiana, a one-room shack that barely managed to remain standing and was labeled “Jim Crow school”; above it appeared a five-column image of Chicago’s integrated Robert Lindblom High School with a row of stately pillars standing tall in front of the modern building. The caption: “One of the many reasons why members of the Race are leaving the south. They are seeking better education for their children, as well as getting away from slavery, Jim Crow laws and concubinage.”31

Another way the dissident editor kept migration mania at a white-hot level was by tying specific acts of racial violence to the escalating pace of the movement. After Eli Persons was burned to death in Tennessee in 1917, Abbott showcased the incident on page one under the exaggerated headline: “Millions Prepare to Leave the South Following Brutal Burning of Human.” Abbott further emphasized his message in the news article that followed, calling Persons’s murder the “last straw” and informing his readers that “thousands are leaving Memphis” in the wake of the heartless crime. Abbott used the same technique after an angry Abbeville, South Carolina, mob killed Anthony Crawford. The headline read “Lynching of Crawford Causes Thousands to Leave the South,” and the story raged, “Respectable people are leaving daily. The cry now is—Go North! where there is some humanity.”32

In other pleas that were part of Abbott’s relentless advocacy of what he called the “Flight out of Egypt,” he appealed to the manhood of his readers. “Every black man, for the sake of his wife and daughters especially, should leave the south where his worth is not appreciated enough to give him the standing of a man.” Other times, the journalistic provocateur urged his readers to see their decision to leave the South as part of history-in-the-making. With this theme, Abbott argued that migration to northern cities would reduce racial prejudice. “Only by a commingling with other races will the black man take his place in the limelight beside his white brother. Contact means everything.”33

Abbott, like other dissident journalists before him, extended his effort to effect social change far beyond publishing. To persuade white employers to hire blacks, the editor gave hundreds of speeches to church and civic organizations in Chicago and other northern cities. Abbott knew these audiences would pay close attention to his appearance and how he comported himself, as he was one of the few middle-class African Americans the white businessmen would come into contact with. So partly to impress those men and partly because he was fastidious by nature, Abbott took great care to dress in expensive suits and hats—finishing off his outfit with gloves, spats, a diamond stick pin, and a gold-headed walking stick.34

By 1919, historian Carl Sandburg was praising Abbott’s leading role in creating the fever for northern migration. Calling the Defender the “single promotional agency” responsible for the historic mass movement, Sandburg wrote in the Chicago Daily News, “There has been built here a propaganda machine that carries on an agitation that every week reaches hundreds of thousands of people of the colored race in the southern states.”35

Historians were not the only ones who connected Abbott with the Great Migration. For in the minds of hundreds of thousands of black Americans, the editor was the messiah who was miraculously raising the quality of their lives. Many of the envelopes being sent from the South did not even mention the Chicago Defender but were addressed simply: “Robert S. Abbott, Chicago, Illinois.” W. A. McCloud of Wadley, Georgia, began his letter by describing Abbott as “a great and grand man and a lover of his race,” while another writer told Abbott, “I feel I know you personally.” Thousands of readers sought Abbott’s counsel—“your paper is all we have to go by,” read one, “so we are depending on you for advise [sic].” Others went well beyond asking for mere words of wisdom. Throngs of African Americans with little knowledge about the world beyond the rural South assumed the “Help Wanted” notices in Abbott’s paper meant that the editor himself was looking for workers; he was besieged with a flood of letters asking him for a job—“I garntee [sic] you good and reglar [sic] service,” a Florida man promised. Hundreds of letters came with requests for Abbott’s recommendation as to where the readers could find suitable housing once they moved to Chicago; some even asked if Abbott himself had a spare room in his own house.36

REAPING THE PERSONAL REWARDS

At the same time that the mass exodus filled the editor’s mailbox and changed America’s demographic landscape, it also transformed the fortunes of Robert S. Abbott. The ambitious editor became one of Black America’s first millionaires, filling his pages with advertisements not only for jobs but also for a wide range of products that appealed to Chicago’s swelling ranks of African American consumers—stylish hats and hair-straightening products for women, suits and sporting goods for men.

As Abbott became one of the nation’s richest and most powerful men of African descent, he made a public spectacle of his wealth and status. He not only dressed ostentatiously but also lived in a massive red brick mansion filled with Hepplewhite antiques and an ebony-finished living room set imported from China. Abbott also took grand tours of Europe and hired a chauffeur to drive him around Chicago in a Rolls Royce limousine. Some people criticized the editor for flaunting his wealth; others praised him for providing a symbol of what a visionary and hard-working black man could achieve in modern-day America—if he lived in the North.

Critics and admirers alike whispered about the details of Abbott’s personal life. His 1918 marriage to Helen Morrison shocked Black America—Abbott was fifty and dark skinned, his wife was twenty and so fair that many people thought she was white. Hoping that his beautiful young bride would produce an heir, Abbott lavished Helen with furs, diamonds, and the latest Paris fashions. But after fifteen years of marriage and no children, Abbott divorced his first wife and quickly married his second. Edna Brown Denison was twenty-five years younger than Abbott and also had light skin—Abbott’s biographer described her as being “as completely white as any Caucasian.” Unlike Helen, however, Edna was a widow with a ready-made family of four children that Abbott treated as his own. At least one detail about Abbott’s personal life cast the dissident editor into the category of “quirky”; he was so formal in his comportment that he never allowed either of his wives to address him, even in the privacy of their own bedroom, as anything but “Mr. Abbott.”37

RESISTING THE BACKLASH

While the migration of half a million African Americans was cause for celebration among Abbott and his followers, it created a crisis for another segment of the population: southern white employers who relied on cheap black labor. Amid predictions of crops rotting in the fields without black workers to harvest them, Alabama’s Montgomery Advertiser spoke for much of the South when it angrily protested: “Our very solvency is being sucked out from underneath us.”38

Unwilling to allow the advancement of African Americans to disrupt their lives and livelihoods, white southerners fought back. The state of Georgia began requiring anyone who recruited southern laborers to purchase a license for the hefty sum of $25,000, and Alabama officials passed a law against “enticing Negroes” to leave the state. Illegal means were used as well, with north-bound trains being sidetracked and African Americans who talked of moving to the North being threatened, beaten, and snatched from railroad stations and arrested as vagrants.39

The Defender did not allow the backlash to go unnoticed. A banner headline on page one announced: “Emigration Worries South; Arrests Made to Keep Labor from Going North.” The Georgia-based story said, “The whites here are up in arms against the members of the Race leaving the south.” The article went on to report that the “bully police” in Savannah were refusing to allow African Americans to enter the local railroad station. “They used their clubs to beat some people bodily,” while arresting others merely for carrying suitcases in the vicinity of the station.40

Much of the white response was aimed at the Defender. In Tennessee, a law made it illegal to read “any black newspaper from Chicago,” and, in Arkansas, the governor charged that the Defender “fomented racial unrest,” prompting a judge to issue an injunction restraining circulation of the paper. Two black men in Georgia were jailed for thirty days merely for having articles from the Defender in their pockets, and at least a dozen African American men were run out of their respective hometowns for trying to sell copies of the paper. When a Texas woman was accused of sending Abbott an article about a lynching, whites burned several black homes and publicly flogged the principal of the town’s black school. In the most serious of the violent incidents, two African American men who sold subscriptions to the Defender in Alabama were attacked and killed by a white mob.41

Abbott received threatening letters such as one from an Arkansas racist who wrote: “You are agitating a proposition through your paper which is causing some of your Burr heads to be killed. You could be of assistance to your people if you would advise them to be real niggers instead of fools.” Southern politicians joined the chorus of criticism. Senator John Sharp Williams of Mississippi called the Defender “a tissue of lies, all intended to create race disturbance and trouble,” Congressman M. D. Upshaw of Georgia denounced the paper as “inflammatory in stirring up race prejudice” and “publishing wild and exaggerated statements about white crimes,” and Senator Edward Gay of Louisiana charged that Abbott was the sole cause of the “unrest at present evident among the negroes of the South.”42

The U.S. government also grew increasingly concerned about Abbott’s paper. Officials in the nation’s capital established a special surveillance operation that combined the forces of the military, postal service, and Justice Department. Because their mutual goal was to maintain national security during World War I and the Defender was a self-declared voice of dissent, the paper was declared “subversive” and emerged as a primary target for federal investigation.43

The efforts to inhibit distribution of the Defender coupled with criticism of it by white southerners, however, also served to assure African Americans of the paper’s courage. When southern leaders forced distribution underground, blacks responded by going to great lengths to obtain the paper. Storekeepers passed copies to customers by hiding them in other merchandise or passing them along surreptitiously. “We have to slip the paper into the hands of our friends,” one distributor wrote. “Every school teacher is closely watched, also the preacher.” Sleeping-car porters played their part, too. When white officials no longer allowed bundles of the Defender to be delivered to railroad stations downtown, the porters began tossing the bundles to agents waiting beside the tracks in rural areas just outside of town.44

Unflinching, the dissident editor fought back from the pages of his paper. With even more ferocity than before, Abbott stridently urged African Americans to come North. “If there ever was a time to strike for freedom in its broadest sense, that time is right now,” he wrote. “If we fail to reap the benefits of this golden opportunity, we have but ourselves to blame.” In another challenge to readers who questioned if they should defy the white southern power structure, Abbott insisted: “Your neck has been in the yoke. Will you continue to keep it there? The Defender says come North.”45

Abbott also countered the backlash with a flow of articles about how blacks who already had joined the Great Migration were prospering in their new environs. One item assured readers that “every one is getting work in the north”; another told of fifteen black families who were thriving in their industrial jobs that paid “sixty to seventy dollars per month, against fifteen and twenty” they had been paid while working longer hours in the South.46

Abbott also continued to report the exodus. A story headlined “Determined To Go North” stated that in Jackson, Mississippi, “Although the white police and sheriff and others are using every effort to intimidate the citizens from going North, this has not deterred our people from leaving. Many have walked miles to take the train for the North. There is a determination to leave and there is no hand save death to keep them from it.”47

A MIXED LEGACY

Robert S. Abbott and the Chicago Defender successfully overcame the antimigration backlash, and the number of southern blacks moving north eventually reached the half million mark.

In 1919, however, Abbott brought his historic campaign to an abrupt halt. He made the decision because of several factors. First, as the influx of African Americans swelled the population of Chicago and other northern cities, those urban metropolises began to strain at the seams. The rapid increase in population created many problems related to crime, health, housing, and education. The large number of blacks suddenly entering American industry during the war also led to difficulty, as organized labor did not fully embrace non-white workers.

The biggest problem of all came, ironically, with the American victory in World War I. That success meant that millions of white soldiers returned home to Chicago and other northern cities to find that the jobs and neighborhoods they had left behind had been appropriated by hundreds of thousands of African Americans. The ebullient young white men were anxious to reaffirm the old caste system; the newly empowered blacks were in no mood to be pushed around. Tension exploded in July 1919 with a four-day race riot in Chicago—the single event that forever changed the tenor of the Defender. The paper’s headlines told the story: “Riot Sweeps Chicago,” “Gun Battles and Fighting in Streets Keep the City in an Uproar,” “Scores are Killed.” When the smoke cleared, fifteen whites and twenty-three blacks lay dead, with 500 others wounded. Although Chicago was hit the hardest, other northern cities felt the crisis as well, with the “Red Summer” witnessing some twenty race riots nationwide.48

So Abbott could no longer, in good conscience, portray his adopted city as the Promised Land. Like the rest of his race, the editor came to see that many of the same problems that existed in the South would persist in the North. Chicago and other industrial cities became yet another location where the Black American Dream was ultimately deferred.

By the fall of 1919, Abbott had lowered the decibel level of his dissidence. From the time of the race riots until his death in 1940, the visionary editor continued to provide a voice for Black America, but that voice no longer defied White America as it had during the height of the Great Migration. Indeed, the paper has continued—becoming a daily in 1956—to be one of the most widely respected black newspapers in the country today.

The historic journalistic crusade the Defender undertook should, by no means, be viewed as a failure. For the mass exodus that the dissident newspaper spearheaded from 1916 to 1919 was a glorious triumph that permanently altered the face of the United States. During a time when the vast majority of Americans of African descent were suffering lives defined by subjugation and terror, the Defender offered its readers a concrete alternative. The nationally circulated black paper inspired hundreds of thousands of men and women to take advantage of a unique opportunity, thereby helping to propel the first major migration in African American history.

And a magnificent migration it was. The flight out of the South did not merely mark a demographic shift. It also signaled the death knell for the feudal existence that most African Americans had been forced to endure, thereby giving them a glimpse, for the first time, of a modern and civilized way of life that was defined by personal as well as racial freedom.

For three remarkable years, the “World’s Greatest Weekly” committed its ample resources to advancing the unprecedented exodus. The courageous newspaper provided, as no other publication in the country, dramatic evidence of the inhumane treatment meted out to southern blacks. The Defender published hard-driving headlines, news stories, editorials, and editorial cartoons, as well as advertisements and feature stories that showcased the employment and leisure-time activities awaiting African Americans who relocated to Chicago. And, finally, the paper harnessed the power of the press to create a migration fever that spread to virtually every city, town, and farming community in the South. The African American men and women who heeded Abbott’s call created new black urban centers in the North that have remained firmly in place, while continuing to grow both in size and impact, since that time.

Robert S. Abbott’s successful effort to transform the lives of half a million people—not to mention the lives of their children and their children’s children—was so remarkable that his leadership of the mass movement has assumed legendary status. Scholars who have studied the 3,000 African American newspapers that have been published during the last 200 years have repeatedly singled out the Chicago Defender’s role in the Great Migration as the most extraordinary achievement in the entire history of this most prolific of advocacy presses.49