This photo from the falsified passport issued to “Bertha Watson” allowed Margaret Sanger to travel under an alias during her year of exile in Europe. (Courtesy Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College)

In the early years of the twentieth century, most abortions were not only illegal but also extremely dangerous, as they often were performed by unlicensed “doctors” under unsafe and unsanitary conditions. But giving birth to numerous children was also a concern because of the physical toll that multiple pregnancies took on the mother and the fact that many parents—especially immigrants who worked in low-paying jobs—could not afford to feed and clothe a large number of children. And yet, despite the dual problems with abortions and unrestricted childbirth, for a woman to prevent herself from becoming pregnant was considered a violation of the laws of both God and nature. Printed information about sex education was branded filthy and obscene, and anyone who dared to send such material through the U.S. mail faced a $5,000 fine and five years in prison.1

It was in this repressive climate that a petite and delicately feminine mother with three small children and all the comforts of the upper class—her husband was an architect, and they lived in an affluent suburban community—founded a dissident magazine dedicated to enlightening its readers about a term that the editor herself coined when she used it in her first issue: birth control.2

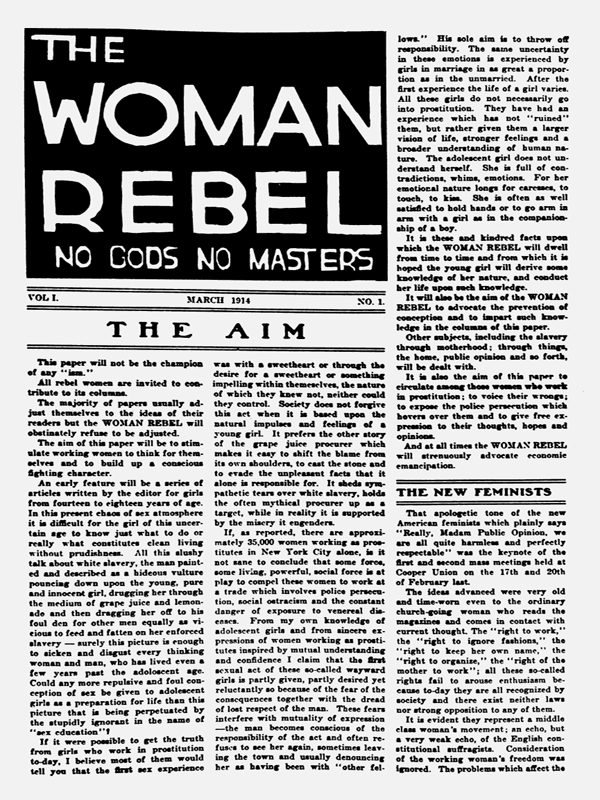

In 1914 when Margaret Sanger began publishing Woman Rebel, she was arrested and denounced as a menace to society. Although law enforcement officials suppressed the magazine and she was compelled to flee from the United States and live apart from her family, Sanger was not deterred from her mission. When she returned from exile, she founded a second magazine, Birth Control Review, to resume her campaign of social insurgency. Indeed, despite opposition from pulpits, courtrooms, newsrooms, and a whole phalanx of fears, myths, pruderies, and dragons of morality that purported to speak for civilized America, Sanger succeeded in publishing her birth control magazines for a quarter of a century while simultaneously founding and leading the Birth Control Movement.

In the inaugural issue of Woman Rebel, Sanger wrote that she was creating the radical monthly because she believed that women were enslaved by motherhood, by childbearing, “by middle-class morality, by customs, laws and superstitions.” To liberate women from that slavery, Sanger wrote, “It will be the aim of the Woman Rebel to advocate the prevention of conception.”3

But Sanger did not stop there.

She demanded that women be allowed to control both their bodies and their minds. “I believe that deep down in woman’s nature lies slumbering the spirit of revolt,” she wrote. “Woman’s freedom depends upon awakening that spirit of revolt within her against these things which enslave her.” In a dramatic front-page manifesto that ran just below her magazine’s bare-knuckled editorial motto “No Gods No Masters,” Sanger boldly stated, “The aim of this journal will be to stimulate working women to think for themselves and to build up a conscious fighting character.” Sanger challenged women “to look the whole world in the face with a go-to-hell look in the eyes” and “to speak and act in defiance of convention.”4

With those mutinous words, Margaret Sanger—a woman who was so meek in appearance that observers said she seemed “about as dangerous as a little brown wren”—set out on the odyssey that transformed her into an icon among feminists and humanitarians alike. Throughout her journey, the core of Sanger’s message would remain the same: Women need information about birth control.5

To a degree reminiscent of the abolitionist press being synonymous with William Lloyd Garrison and the anti-lynching press being synonymous with Ida B. Wells-Barnett, the story of the birth control press is the story of Margaret Sanger.

EMERGENCE OF A WOMAN REBEL

Margaret Higgins was born in 1879 into a devout Catholic family headed by Michael Higgins, a stonecutter who operated his own business, and Anne Higgins, a homemaker who cared for the family’s Corning, New York, home.6

Although Margaret initially studied at a private boarding school, her mother’s chronic tuberculosis grew so severe that the girl was brought home to care for her younger siblings. Margaret’s earliest childhood memory was of a mother wasting away because constant pregnancies—she gave birth to eleven children and lost seven more to miscarriages—prevented her from gaining the physical strength necessary to resist the disease that afflicted her. “My mother died in her forties,” Margaret later said with a sense of bitterness, “but my father enjoyed life till he was in his eighties.”7

At age nineteen, Margaret enrolled in nursing school. Her soft brown eyes and abundance of charm and wit, however, attracted so many young men that she struggled to remain focused on her studies. Six months after meeting William Sanger, the most persistent of her suitors, she dropped out of school and married him. For the next eight years, the Sangers lived in a spacious home in fashionable Hastings-on-Hudson just up the river from New York City. William worked the long hours that were expected of a young architect in the prestigious firm of McKim, Mead & White; Margaret assumed the role of supportive wife and mother, producing and caring for two sons and a daughter.

By 1910, the four walls of the Sanger home had become too confining for Margaret, so she began working for the Visiting Nurses Association. The job took her into the immigrant tenements on New York’s Lower East Side, revealing a pathos of poverty and human deprivation previously unknown to her.

This photo from the falsified passport issued to “Bertha Watson” allowed Margaret Sanger to travel under an alias during her year of exile in Europe. (Courtesy Sophia Smith Collection, Smith College)

Working-class women, Sanger quickly learned, often had no idea how to avoid becoming pregnant, even though upper-class women such as herself were fully aware of several options. Pharmacies sold rubber condoms that could be placed over a man’s penis and rubber shields that could be placed in a woman’s vagina. Doctors and nurses also could fit women with diaphragms, and women themselves could use sponges and spermicidal douches, powders, and jellies. More basic methods included a man withdrawing his penis before ejaculation and couples practicing the rhythm method of avoiding intercourse during fertile phases of the woman’s menstrual cycle—and yet many working-class women were totally unaware of these precautions against pregnancy.

Soon after Sanger began her job as a visiting nurse, she met Sadie Sachs. The young Jewish immigrant had three children and was dangerously ill from blood poisoning brought on by an illegal abortion. By giving Sachs around-the-clock attention for three weeks solid, Sanger nursed her back to health. When Sachs had regained her health, she begged her doctor to tell her how to avoid another pregnancy, but he refused; to provide information about contraception was against the law—even for a doctor. Three months later, Sanger returned to find Sachs weakened by yet another abortion. Sadie Sachs’s subsequent death, at the age of thirty, propelled Sanger to abandon nursing in pursuit of fundamental social change. “A moving picture rolled before my eyes,” she later recalled. “Women writhing in travail to bring forth babies, the babies themselves naked and hungry, wrapped in newspapers to keep them from the cold. I could bear it no longer.” Sanger then made the pledge that charted the course that would dominate the rest of her life: “Women should have knowledge of contraception. I will strike out—I will scream from the housetops.”8

Sanger began screaming by writing about sex education for the New York Call, a socialist newspaper. In her “What Every Girl Should Know” column, Sanger tackled taboo topics—from pregnancy and abortion to menstruation and masturbation—with a candor totally at odds with the conservative mores of proper society.

A piece on venereal disease attracted the most attention, as it provoked a response from Anthony Comstock. During his forty years as U.S. Post Office Inspector, the country’s most notorious public censor had convicted some 3,000 men and women on obscenity charges. Comstock banned Sanger’s February 1913 column, prompting the Call to publish an empty box below the headline “What Every Girl Should Know—Nothing: by order of the U.S. Post Office.” It took several weeks of legal wrangling before the column finally made it into print.9

Sanger’s confrontation with Comstock catapulted her into the public spotlight while at the same time strengthening her resolve to make sex-education information available to the poor women who so desperately needed it. After several months of talking with the various voices of political and cultural ferment who were living in bohemian New York City, Sanger founded the magazine that would win her a place in the history of the dissident press.

The first issue of Woman Rebel appeared in March 1914, and it was immediately evident that Sanger had succeeded in her stated goal of making her publication “red and flaming.” The eight-page magazine berated the criminal sanctions imposed on contraception and attacked the institutions of marriage and motherhood as negative forces that limited women’s opportunities. Sanger looked beyond economic and political arguments to promote an autonomy for women that required wholesale change in attitude and behavior.10

Sanger’s rebellious tone ensured that at least the outlines of her message would be heard beyond the few hundred people who subscribed to Woman Rebel because a spate of sensational news stories in the mainstream press expressed outrage at her journalistic venture. Establishment papers called Sanger a “vile menace” and “raving maniac” who was “determined to explode dynamite under the American home,” while they declared her campaign for wider access to birth control information “brazen heresy.” The archetype comment in the daily press appeared in a Pittsburgh Sun editorial about Woman Rebel: “The thing is nauseating.”11

The most significant response came from Comstock. He confiscated the first issue and notified Sanger that he would prosecute her if she continued to publish her magazine. She defied the ruling by editing more issues of Woman Rebel, surreptitiously dropping copies into mailboxes throughout the city in an effort to avoid detection. In August 1914, police arrested her on felony counts for publishing nine specific articles deemed to be indecent. The charges carried a combined sentence of forty-five years in prison.

As Sanger’s October trial date approached and her erstwhile supporters—doctors, socialists, feminists—all abandoned her, she decided to flee from the authorities and live abroad until the political climate at home improved, even though that meant allowing Woman Rebel to die. It was not surprising that she was willing to separate from her husband, as their love had faded and she had begun an affair with Walter Roberts, a poet and journalist, in 1913. More difficult to understand was Sangert’s decision to leave New York without even saying goodbye to her three small children—Stuart was ten, Grant six, Peggy four.12

Although the format was conventional, the name Woman Rebel and the editorial motto “No Gods No Masters” clearly defined Margaret Sanger’s first magazine as a member of the dissident press.

During 1915, Sanger lived in Europe under the nom de guerre “Bertha Watson.” She devoted her days to research at health institutions in France and England, which were more enlightened about contraception than was the United States. At night, the winsome “Bertha” enjoyed a carefree life with one or the other of her two lovers. The first was a Spanish radical named Lorenzo Portet, the second the distinguished British psychologist Havelock Ellis—both men were married at the time, as was Sanger.13

After a year abroad, she returned to New York partly because she had premonitions about her daughter suffering from poor health. The mother’s instincts proved all too prescient when Peggy contracted pneumonia a month after her mother came back to the United States. Peggy’s death late that year had major impact on Sanger’s personal life, as her two young sons both blamed their sister’s death on their mother’s prolonged absence. Sanger placed both boys in boarding school.

Sanger’s legal problems evolved more satisfactorily. After she returned to America, the beautiful and articulate woman became the toast of the country’s social and intellectual elite. With such prominent supporters as authors Pearl S. Buck and H. G. Wells, philanthropist Juliet Rublee, society matrons Frances Tracy Morgan and Alva Smith Vanderbilt Belmont, and suffragist Harriet Stanton Blatch (Elizabeth Cady Stanton’s daughter), Sanger took on the aura of a celebrity whose every legal maneuver produced a flurry of news stories. Government prosecutors became concerned that Sanger would become a popular martyr, so they dropped all charges.

Buoyed by that victory and her growing public profile, Sanger orchestrated a massive campaign to make contraceptive material available to all women. The diminutive Sanger—she stood only five feet tall and weighed barely 100 pounds—led mass rallies on the streets of New York and then set off on a national speaking tour that included some 120 lectures.

In October 1916, Sanger rented a building in the Brownsville section of Brooklyn to establish the country’s first birth control clinic. This defiant act led to her immediate arrest, as she had broken the law by disseminating birth control information. Found guilty under the Comstock laws, Sanger spent thirty days in the Queens County Penitentiary.

Sanger’s time in jail was not in vain. The judge who ruled that she had broken the law wrote in his decision that, while laypersons such as Sanger did not have the legal right to dispense contraceptive advice, licensed physicians did. Sanger had, in short, succeeded in opening the door that previously had been securely barred. No longer would doctors have to fear being sent to jail for responding to pleas such as the one by Sadie Sachs.

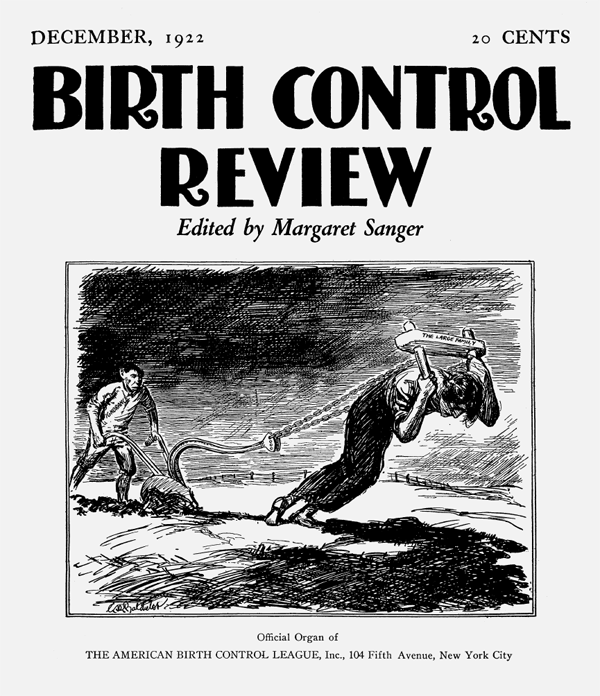

In February 1917, Sanger founded her second monthly magazine. “Birth control is the most vital issue before the country today,” she wrote in the inaugural issue. “The men and women of America are demanding that this vitally needed knowledge be no longer withheld from them, that the doors to health, happiness, and liberty be thrown open and they be allowed to mould their lives, not at the arbitrary command of church or state, but as conscience and judgment may dictate.”14

Birth Control Review was a continuation of Woman Rebel, although solid financial and political support from Sanger’s well-heeled benefactors ensured that the second publication would survive far longer than the first, ultimately being published without interruption for twenty-three years. The combined content of the two magazines articulated the themes that defined the social movement she had ignited.

PROVIDING VITAL INFORMATION TO WORKING-CLASS WOMEN

During Sanger’s many years as a dissident journalist, she would repeat the central premise of her movement hundreds of times. The first of those instances came in the lead editorial of the first issue of Woman Rebel in 1914. The headline read “The Prevention of Conception,” and the editorial itself began with Sanger asking the disarmingly simple question: “Is there any reason why woman should not receive clean, harmless, scientific knowledge on how to prevent conception?” Sanger then continued, “The woman of the upper class has all available knowledge and implements to prevent conception, but the woman of the people is left in ignorance of this information.” The intrepid editor went on to tell how only upper-class women had access to the subrosa grapevine of information about birth control, forcing working-class women to turn to “bloodsucking men with M.D. after their names” who performed abortions in shadowy back alleys with “no semblance of privacy or sanitation.”15

Sanger concluded her editorial by exposing the real reason, in her mind, that the financiers and industrialists who ran the United States conspired to deny birth control information to the underclass: Capitalism would survive only as long as poor women continued to produce masses of children who did not receive proper educations and were thereby doomed to become the next generation of laborers to grind away their lives in the nation’s factories. “No plagues, famines or wars could ever frighten the capitalist class,” Sanger wrote, “so much as the universal practice of the prevention of conception.”16

The “little brown wren” did not mellow as the years passed. Indeed, Sanger became even more vehement in her demand that women on the lowest rungs of the socioeconomic ladder be told how to prevent pregnancy. In a 1920 Birth Control Review editorial titled “A Birth Strike To Avert World Famine,” she took one of the most radical steps in a career paved with many of them, calling for every woman in America to pledge that not a single baby would be born anywhere in the country for the next five years. “Each woman who is awake to the true situation,” Sanger insisted, “should make it her first task to encourage and to assist her sisters in avoiding child bearing until the world has had an opportunity to readjust itself.”17

The impassioned editor did not limit her campaign to her own words only but also opened the pages of her magazines to her readers. “The following letters are published to illustrate the deep interest in and widespread demand among women of the working class for knowledge concerning birth control,” Sanger said in a note above a typical batch of letters. A California woman wrote: “Enclosed find ten cents, for information of how to prevent conception. I am nearly crazy with worry from month to month.” An Illinois woman made the same request: “I am the mother of six children. I am not well enough to have any more. Will you please send me information so I can prevent me having another child.”18

Sanger responded to the plaintive cries in two ways. Woman Rebel and Birth Control Review continually denounced the laws that made it illegal to provide women with birth control information. The founder of the Birth Control Movement wrote that her magazine did not print contraceptive information because, “It is illegal in this country to give such information. This law is obsolete, pernicious, and injurious to the individual, the community and the race. The law must be changed.”19

Sanger’s second form of response was direct and immediate. When a reader requested contraceptive information, Sanger sent back a personal letter advising the woman where she could find the answers she needed. In most cases, that meant providing the name and address of the nearest physician willing to provide birth control material. If the woman was isolated from all sympathetic doctors, Sanger herself sent the requested information—thereby breaking the law.

CONTRIBUTING TO THE ILLS OF SOCIETY

Supplying working-class women with birth control information would not only ease the difficulties that individual women faced, Sanger contended, but also would help alleviate a long list of social ills that plagued American society.

One of the fundamental messages of the birth control press was that ignorance of contraceptive methods condemns a mother to the deprivation of a family larger than she can reasonably support.

Paramount among those problems was poverty. As long as poor women remained ignorant of how to prevent pregnancy, Sanger insisted, they would continue to give birth to more children than they could afford to raise and therefore would have to endure lives of hardship and desperation—as would their children. Typical was an article Sanger wrote for Woman Rebel, titled “A Little Lesson for Those Who Ought to Know Better,” that used an easy-to-follow format consisting of brief questions and correspondingly brief answers. The piece asked: “Why should people only have small families?” And then answered: “In order to be able to feed, clothe, house and educate their children properly.” Sanger sprinkled such simple and succinct statements throughout her magazines. A piece titled “Can You Afford to Have a Large Family?” included the sentence: “Science teaches us that there are innocent but safe methods by which parents can control the size of their family,” and an article titled “Into the Valley of Death—for What?” included the sentence: “As long as the working class bears children, this fact alone will keep it in poverty.”20

Closely related to economic deprivation was the problem of prostitution. Young women still in their teens or early twenties who found themselves with two or three tiny mouths to feed, Sanger wrote, still longed to wear the “pretty colored ribbons, fluffy lace, bangles, beads and bracelets” that were the trappings of single girls of the same age. Many young women who struggled to balance their responsibilities as mothers against their desires as young women, Sanger continued, eventually sold their bodies as prostitutes, thereby becoming more victims of capitalism’s “cruel system of ignorance and greed.”21

The most dire item on Sanger’s list of shameful social ills was abortion. For while the guiding spirit of the Birth Control Movement encouraged women to prevent unwanted births, she adamantly opposed ending human life after the point of conception. Sanger’s objection evolved not from moral concerns but from fear about the physical well-being of women who aborted their unborn babies. Of the 150,000 abortions that occurred in the United States annually during the early years of the twentieth century, one in six ended in the woman’s death. “Abortions, with their horrible consequences, would be quite needless and unnecessary if the subject of preventive means were open to all to discuss and use,” Sanger wrote. “What a wholesale lot of misery, expense, unhappiness and worry will be avoided when women shall possess the knowledge of prevention of conception!”22

ACCESS TO BIRTH CONTROL AS A FEMINIST ISSUE

Throughout her quarter century as a dissident journalist, Sanger relentlessly championed a proposition that is still controversial today but in the early twentieth century was nothing short of heresy: A woman should have the right to control her own body.

In a statement that could just as easily appear in a women’s liberation publication today, Sanger wrote on the front page of Woman Rebel almost a century ago: “A woman’s body belongs to herself alone. It is her body. It does not belong to the United States of America.” Relating the issue to a woman’s right to have access to birth control, Sanger continued, “Enforced motherhood is the most complete denial of a woman’s right to life and liberty.”23

Not surprisingly, Sanger’s ahead-of-her-time position on the issue of reproductive rights was at odds with the Catholic Church that she had grown up in but had later abandoned. “The Catholic Church is one of the greatest enemies against the achievement of woman’s economic, intellectual and sexual independence,” she wrote. “The Church denies personal liberty to women.” In one article, Sanger even went so far as to accuse Catholic priests of opposing birth control solely to counteract their own “impotency anxiety.”24

The most frustrating of the conflicts that grew out of Sanger’s unyielding support of a woman’s right to control her own body was with most feminists. Sanger derided the Women’s Rights Movement as “sadly lacking in vitality, force, and conviction” because its platform was limited to what she considered to be the “frivolous” concerns of middle- and upper-class women, such as winning “the right to ignore fashions.” Sanger supported a much more militant agenda, insisting that “women’s organizations will never make much progress until they recognize the fact that women cannot be on an equal footing with men until they have full and complete control of their reproductive functions.”25

DEFYING OBSCENITY LAWS

Sanger knew when she entered the rough-and-tumble world of advocacy journalism that her publishing effort would provoke legal action against her. The lead editorial of the premier issue of Woman Rebel in March 1914 ended with Sanger acknowledging that discussing contraception in print was illegal, followed by a pair of rhetorical questions that virtually dared post office officials to arrest her: “Is it not time to defy this law? And what fitter place could be found than in the pages of the WOMAN REBEL?”26

The second issue contained equally brazen references to Woman Rebel’s intentional flouting of obscenity laws, with Sanger beginning the lead story with several mocking statements: “The Postmaster did not like the first number of the Woman Rebel. He is empowered by the federal government to stop the circulation of any printed expression of honest convictions. It is a crime to have honest convictions in these United States.” Sanger’s rhetorical burlesque continued: “The Woman Rebel realizes that the Post Office is always ‘right,’ since it has the monopolized power to enforce that ‘right.’ Therefore the Woman Rebel, humbled and repentant, curtseys coyly to the Postmaster and apologizes for the expression of any opinion that is unmailable.”27

Neither the subsequent suppression of Woman Rebel nor Sanger’s arrest on obscenity charges diminished the editor’s defiance. The July issue contained more jeering. “If you fail to receive any number of this magazine,” Sanger told her readers, “you may conclude that the United States Post Office has decided that it is not fit for you to read. We suggest that all readers write to the Postmaster General and express appreciation for the kindly interest taken by the Post Office in keeping you pure and virtuous by prohibiting you from reading any matter that is adulterated with the truth. Our benign Government is certain that the truth is not only poisonous but obscene.”28

In the final issue of Woman Rebel that Sanger edited before fleeing to Europe, she again attacked the inanity of birth control information being censored. A front-page story told how Sanger had been arrested and was scheduled to be tried. The mocking tone was now absent, but Sanger’s insolence remained very much intact. “We are witnessing the arch-hypocrisy of the United States flattering itself upon its ‘civilization’ yet stamping out every glimmer of intelligence, and stifling any honest expression of thought.”29

“THE OUTSTANDING SOCIAL WARRIOR OF THE CENTURY”

At the same time that Sanger was promoting her cause through her magazines, she was continuing to lead the social movement that she had founded. She was the driving force behind a series of national birth control conferences, and in 1922 she incorporated the American Birth Control League as a non-profit charitable institution that provided services to individual women and also encompassed public education, legislative reform, and medical research related to contraception. Within a decade, the league had grown to include scores of clinics nationwide.30

Sanger’s personal life continued to be as nonconformist as the social movement she led. During her early years of editing Birth Control Review, she had an affair with Billy Williams, a former reporter who helped her raise money. In 1920, she had sexual liaisons with Hugh de Selincourt, a handsome and debonair novelist, and H. G. Wells, the novelist and essayist who had reached the pinnacle of his career as one of the best known writers in the world.31

Sanger’s personal life settled down—up to a point—in 1921 after she met Noah Slee, a millionaire businessman who owned the company that manufactured Three-in-One household oil. Although Slee had been married for thirty years, he was instantly beguiled by Sanger. Slee and Sanger then divorced their spouses, married each other, and began a new life together in a long, rambling stone house overlooking a lake in upstate New York.

Sanger and Slee made an improbable couple. She tended to be irreverent and fun-loving, he staid and sober. She was an atheist, he a pillar of the Episcopal Church. She was a member of the Socialist Party, he a Republican. Although she bewildered and often exasperated him, he found her irresistible. She gave him satisfaction in love, and he provided her with ample funds to pour into her magazine. Slee also was generous with Sanger’s two sons, helping finance their college educations.32

On their wedding day, Slee signed an agreement that his wife would, in all respects, maintain her personal freedom as well as her own name. Throughout more than twenty years of marriage, which ended only with Slee’s death in 1943, he held to this contract. The extent to which Slee was aware of his wife’s affairs with numerous men during their marriage—including Wells, de Selincourt, journalist Harold Child, and businessman Angus Sneed MacDonald—is not clear.33

Sanger’s infidelity was not widely known at the time, and New York’s high society continued to support her. Indeed, the Birth Control Movement’s most beneficent patrons were the wealthy socialites who had been entranced by the charming and diminutive woman who wore simple and classic little black dresses—“The more radical the ideas,” Sanger believed, “the more conservative you must be in your dress.”34

By the mid-1920s, the dissident editor was being lionized in the national press as a brave clarion of social progress. “She is, by far, now and from the beginning, the ablest and the most effective friend that the cause of Birth Control has ever had,” gushed the tony New Yorker magazine in a 1925 profile. “To see her, one is astounded at her youth, at her prettiness, her gentleness, her mild, soft voice.” Even more important than the praise of Sanger was the positive treatment that the subject of birth control had begun to receive in the mainstream press—largely because of its founder. The New Yorker led the way, saying, “She has carried her crusade for birth control through from the time when simply to mention it was to invite imprisonment to the time when, ten years later, it has every contour of calm respectability.” Other publications followed suit. In 1926, the New York Times wrote facetiously that “the terrible Margaret Sanger whom thousands of the pious have been taught to regard as the female Antichrist” was, in reality, “engaged in no more iniquitous enterprise than the effort to help people be happy.”35

This flattering press coverage helped establish Sanger as a popular lecturer. Billed by her booking agent as “The Outstanding Social Warrior of the Century,” she crisscrossed the country addressing civic and women’s groups while simultaneously helping to create dozens of local birth control clinics. Passage of the Nineteenth Amendment giving women the right to vote, in 1920, added to the momentum of her cause; having finally cleared the suffrage hurdle, even moderate feminists were then willing to adopt winning a woman’s right to control her own body as their next goal.

But still, Sanger continued to pay a high price for the headway she was making. On numerous occasions, she made advance arrangements to speak in a particular city but then discovered, shortly before the appointed hour, that local law enforcement officials had canceled the reservation she had made at the designated auditorium. In each case, she fought the efforts to muzzle her by facing down the authorities, often by speaking from the steps of city hall or the police station. Although her audacity netted her an arrest on charges of disorderly conduct, she accepted the citation gladly. For she ultimately succeeded in drawing an even larger crowd than she would have had she been allowed to speak at the auditorium she had initially reserved.

And the progress continued.

By the early 1930s and as Birth Control Review’s circulation topped 30,000, both Sanger and her cause were being embraced by large segments of the public. In 1931, the American Woman’s Association awarded Sanger its prestigious medal of honor in recognition of her “vision, integrity and valor.” The accompanying citation read: “Margaret Sanger has devoted her life to the highest of all pursuits, the betterment of social welfare. She has opened the door of knowledge and thereby given light, freedom, and happiness to thousands caught in the tragic meshes of ignorance. She is re-making the world.” The New York Herald Tribune promptly ran an editorial labeled “She Deserves It” that read: “Mrs. Sanger has carved, almost single-handed and in the face of every variety of persecution, a trail through the densest jungle of human ignorance and helplessness. Her victory is not by any means complete, but the dragons are on the run.”36

This support from the public and the media propelled birth control onto the national agenda. Once placed in that spotlight and with Sanger’s loud and dogged advocacy, the triumphs began. In 1930, the Anglican Church reversed its long-standing position and officially sanctioned the use of contraception, and a year later the Church of Christ did the same. In 1935, the General Federation of Women’s Clubs gave its support, as did the Young Women’s Christian Association. And then came the watershed year of 1936. First a national poll found that seventy percent of Americans supported the use of birth control, and then a landmark legal decision by a New York Appeals Court reinterpreted the Comstock laws to establish that birth control information was not obscene and, therefore, could be distributed through the mail.

Each time mainstream news organizations recorded one of these victories, they gave due credit to Sanger—and then competed to see which of them could sing her praises loudest. Time magazine dubbed Sanger “tireless,” and The Nation weighed in with “valiant.” Life magazine ran a four-page photo essay chronicling Sanger’s life and bubbling, “That there are today 320 birth control clinics in the U.S. is due largely to this single-minded woman’s ceaseless efforts.” The New York World-Telegram applauded Sanger’s “fiery belligerence” that had successfully transformed a “frail, sweet-faced” mother into the “general” at the vanguard of the Birth Control Movement.37

A LEGEND IN HER OWN LIFETIME

Many dissident journalists do not live long enough to witness how their revolutionary ideas filter into the mainstream of American thought. Margaret Sanger did.

By the time the editor of Woman Rebel and Birth Control Review died of arteriosclerosis in 1966, at the age of eighty-seven, birth control had become an accepted element in modern-day life. One out of every three non-Catholic American women of child-bearing age was routinely using an oral contraceptive, and an untold number of others were using diaphragms or interuterine devices. What’s more, the American Birth Control League that Sanger had founded in 1922 and had transformed into Planned Parenthood in 1946 was operating hundreds of centers nationwide—plus ninety projects outside the United States.

Sanger was also instrumental in the development of the birth control pill. At a masterfully orchestrated dinner party in 1951, she introduced Katharine McCormick, the wealthy daughter-in-law of the inventor of the mechanical reaper, to Gregory Pincus, a fertility expert who ran a small and underfunded research institute. By evening’s end, McCormick wrote Pincus the first of many hefty checks bearing her signature. And nine years later, Pincus brought the Sanger-inspired dream of the “perfect” contraceptive to fruition.

Although it would be an exaggeration to attribute all of these successes and the complete sea change in America’s attitude toward contraception to the “little brown wren,” the New York Times came close to doing exactly that in the front-page obituary that it ran to record the activist editor’s death. “As the originator of the phrase ‘birth control’ and its best-known advocate, Margaret Sanger survived federal indictment, a jail term, numerous lawsuits, and hundreds of raids on her clinics to live to see much of the world accept her view that family planning is a basic human right.”38

It would have been difficult for someone reading those laudatory comments to reconcile them with the statements that the nation’s leading newspapers had made about Sanger half a century earlier—that she was a “vile menace” and “raving maniac” whose magazine was nothing short of “nauseating.”

Beginning in 1914 with the founding of Woman Rebel and continuing with an indomitable sense of purpose for the next several decades without retreating a single inch, Sanger used the power of the printed word to give voice to the voiceless and to spearhead her triumphant campaign to convince a recalcitrant America that a woman’s right to control conception, her body, and her very self is a right that must be available not only to the upper-class woman who commands wealth and power, such as Margaret Sanger, but also to her poor and powerless working-class sister, such as Sadie Sachs.