The Paper in East Lansing, Michigan, was one of many counterculture publications that eagerly celebrated the rise of the drug culture during the 1960s.

The Vietnam War was by no means the only force challenging the established order during the 1960s. Race, gender, class, personal freedom, the work ethic, recreational drugs, the nature of consciousness—they were all on the table as social turbulence fueled a zeal for self-expression, a disdain for authority, and a mistrust of conventional wisdom that came crashing together to form the Counterculture Movement.

Some of the young rebels belonged to organizations, such as the Students for a Democratic Society, that sought to build a New Left constructed on a desire for fairer, more equitable political relationships in the larger society. Others found their identities as hippies, focusing on changing themselves via chemicals, meditation, and alternative lifestyles. At the core of both camps stood committed activism, a robust spirit, passion for change, and three concepts that the counterculture celebrated and the dominant culture condemned: sex, drugs, and rock ‘n’ roll.

Despite the significance of the infectious rebellion, the mainstream media were slow to recognize it as a newsworthy phenomenon. The country’s leading journalistic outlets ridiculed the young activists and ignored the injustices the movement was attempting to correct. Owned by corporations that were part and parcel of the establishment, many major media voices inherently favored the status quo and, therefore, opposed the social change the Counterculture Movement advocated.

So, some 500 brash and boisterous newspapers came on the scene for the twin purposes of recording the activities of the movement and playing a central role in creating the vibrant new culture that was utterly at odds with many conventional American values.1

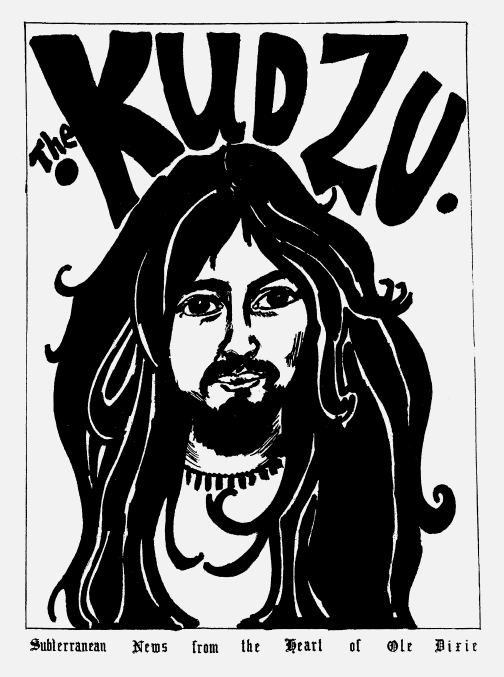

One of the largest, most influential, and longest lasting of the papers was the Berkeley Barb, founded in 1965 near the campus of the University of California at Berkeley. Another strong voice that emerged from a major campus community was The Paper, which began publishing in 1965 in East Lansing, home of Michigan State University. A third member of this lively genre of the dissident press was The Kudzu, founded in 1968 in Jackson, Mississippi, to provide a counterculture voice in the Deep South.

These publications—all tabloids—represent three distinct types of papers. Some, like the Barb, were financially independent publications that relied on advertising revenue and demonstrated strong commitments to the communities that surrounded them. Others, like The Paper, received university funding, for at least part of their histories, and devoted much of their editorial attention to issues on their particular campus. Still others, like The Kudzu, were hippie papers that struggled to survive with scant advertising, no university funding, and a small readership confined to a tiny slice of the population.

The counterculture papers were often amateurish or rag-tag in appearance, with many words misspelled or misused, as well as headlines and graphics frequently drawn by hands that lacked artistic talent. The late-night deadlines and liberal drug use also meant that various details, such as numbering the pages, slipped through the cracks. Other creative touches, such as articles being placed upside down or sideways on the page, were not accidents but deliberate expressions of an anti-establishment approach to journalism.

“Wild-and-woolly” was another apt description for the papers. Slang and coarse language were sprinkled liberally into news stories as well as the personal essays that dominated the papers. Drawings and photographs of naked women added gratuitous titillation; between the staff box and an editorial cartoon on page two of The Paper, the editors frequently placed a photo of a voluptuous young woman, her breasts and genitalia fully exposed. Demeaning references to women—such as “broads” and “babes”—were also strewn through the publications, which were edited almost exclusively by men.2

In keeping with the Counterculture Movement’s emphasis on self-expression, the papers lifted personalized journalism to a new high. After discussing several of the songs on a new Beatles album, an exhausted music reviewer on the staff of The Kudzu who identified himself only as “Allan” wrote: “I’m not going to continue like this since its [sic] almost 2:30 am Saturday morning. I’ve got 3 big tests next week, 2 papers, and an infant puppy. Buy the goddamn album and form your own opinions.”3

Technological advances threw open the floodgates for a new wave of media activism. Since the mid-nineteenth century, newspaper copy had been set in hot lead type on a Linotype machine and then printed on a huge press, a system that required technical training and a major financial investment. But the introduction of cold-type printing in the early 1960s made newspapers quick, easy, and cheap to produce. Anyone with a typewriter could prepare copy and paste it onto flat sheets of paper that could then be photographed and duplicated for only a few dollars.

BERKELEY BARB: IGNITING THE REVOLUTION

Considering that “Don’t trust anybody over thirty” was the mantra of the Counterculture Movement, it is ironic that the founder of the best known of the papers was a balding, fifty-year-old family man. Throughout the early 1960s, Max Scherr had joined the youthful patrons at his Steppenwolf Bar in complaining about the conservative policies that defined not only the nearby University of California but also local, state, and federal politics. In addition, Scherr had become increasingly frustrated with the widening gap that separated the era’s newspapers from the readers they claimed to be serving.

So in August 1965, Scherr sold his bar for $10,000 and used the money to start a weekly paper aimed at young people. He dubbed his publishing enterprise the Berkeley Barb, choosing the second word in the name carefully; like the sharply pointed projection on an arrow, he wrote, the Barb would “nettle that amorphous but thickhided [Scherr later said that he had meant ‘thick-headed’] establishment that so often nettles us.”4

Hundreds of other voices of the counterculture would soon emulate the editorial mix that Scherr had pioneered. News coverage was dominated by sympathetic articles about anti-Vietnam War rallies and exposés of brutality by the local “fuzz.” An abundance of music reviews alongside eye-catching photos and psychedelic drawings added considerable spice. But the defining editorial element in the Barb was the plethora of personal essays written from a decidedly and unapologetically anti-establishment point of view.

The Barb’s size and reputation skyrocketed in May 1969 because of a controversy that focused national attention on Berkeley. The incident began when hippies and street people planted trees and flowers in a university-owned vacant lot that had been slated to be used for a soccer field and dormitories. Scherr catapulted the local conflict into the national news spotlight by promoting it as the quintessential David-versus-Goliath story, while clearly siding with the underdog through blatantly biased comments such as: “The creators of our Park wanted nothing more than to extend their spirits into a gracious green meandering plaything. They wanted to make beauty more than an empty word in a Spray Net commercial.”5

The Barb’s rhetoric contrasted sharply with that of the stodgy Berkeley Gazette, which focused its coverage on what the paper considered appalling behavior by the hippies: “Several persons openly smoked pot, nearby residents reacted with shock and dismay.”6

Police and National Guard troops were called in to get rid of the “riffraff,” prompting 20,000 students to gather for a peaceful protest. When police intervened and killed one demonstrator and injured several others, public opinion joined the Barb in the hippie camp. By the end of the volatile thirteen-day siege, Governor Ronald Reagan finally sent the troops home, the university revised its plans and turned the property into a park, and the Berkeley Barb had a worldwide reputation as a triumphant journalistic defender of the people.

That incident and the paper’s lively editorial mix were a winning combination. By late 1969, the paper was being distributed nationwide with a circulation of 93,000, and Scherr was employing a staff of forty. The Barb was on firm financial ground as well, with a wealth of retail ads from local merchants and major national companies eager to reach well-heeled college students. An abundance of classified ads also offered a wide range of items and services—many of them sexual.

THE PAPER: SPREADING THE MOVEMENT

INTO THE MIDWEST

A counterculture paper founded only a few months later than the Barb was edited by a very different type of person and in an equally distinct part of the country.

Michael Kindman had left his home on Long Island to study journalism at Michigan State University, one of 200 National Merit Scholars the huge land-grant institution had aggressively recruited to upgrade the MSU academic reputation and, it hoped, shed the disparaging nickname “Moo U.” But after arriving in East Lansing, Kindman decided he’d been hoodwinked. A dearth of cultural and intellectual stimulation combined with a stodgy journalism curriculum and student newspaper made Kindman restless to become part of the counterculture that he heard was beginning to catch fire on other campuses around the country.7

So in December 1965, Kindman resigned from the Michigan State News and founded The Paper. He fashioned his debut editorial after Max Scherr’s first statement about the Barb: “We hope unabashedly to be a forum for ideas, a center for debate, a champion of the common man, a thorn in the side of the powerful.”8

The Paper in East Lansing, Michigan, was one of many counterculture publications that eagerly celebrated the rise of the drug culture during the 1960s.

Michigan State helped fund The Paper because it was a student endeavor, as all staff members were enrolled at the university. Editorial content reflected the weekly’s strong interest in campus affairs, making The Paper an early champion of students having a say in how their institutions functioned. Alongside the stories and editorials supporting student rights, The Paper published a spirited mélange of articles, reviews, and artwork much like that of the Barb and other counterculture papers—by 1966, Time magazine was derisively comparing the publications to a blight of pesky “weeds” and criticizing their editors as “political zealots.”9

The Paper’s journey into the counterculture coincided with Michael Kindman’s personal odyssey into the drug culture. He took his first LSD trip and began using acid within a year of becoming a dissident journalist and was soon spending more time tripping than studying. “More and more of us were exploring taking drugs and being stoned together,” Kindman later wrote of the staff. “We just got off on all the fun we were having, exploring the corners of our minds and finding new meanings in everything we looked at.”10

In 1966, The Paper published a high-profile article that cogently combined its anti-university and anti-Vietnam War positions. The story evolved from a Ramparts piece, the magazine’s latest blockbuster about the roots of the war, that exposed a secret alliance between Michigan State and South Vietnamese dictator Ngo Dinh Diem. According to Ramparts, MSU professors had trained Diem’s police, drawn up his budget, and written his constitution—all with U.S. money funneled through the CIA. The magazine reprinted an MSU inventory that included tear gas projectiles, .50-calibre guns, grenades, and mortars. The withering nine-page indictment ended with the poignant question: “What the hell is a university doing buying guns, anyway?”11

When Michael Kindman saw the Ramparts exposé, he knew he had the makings of a major story. So he summarized the national magazine’s accusations juxtaposed against the milquetoast defense that the university published in the Michigan State News. And along with the huge story blanketing page one, The Paper printed a full-page caricature of a Vietnamese woman as a buxom MSU cheerleader beside the statement: “The story of a sellout. The April issue of Ramparts chronicles how and why Michigan State University abdicated its integrity in a calculated search for gold and glory in Vietnam.”12

It surprised no one when MSU axed The Paper’s university funding. The publication’s finances remained stable, however, because the staff agreed to work for free and the printing costs were covered by the revenue from the paper’s 5,000 paid subscriptions and the bountiful advertising from local and national companies that, like those in Berkeley, were eager to reach the highly desirable college-student market.

THE KUDZU: CREATING A BEACHHEAD IN THE DEEP SOUTH

One of the ways a third member of the counterculture press differed from the Barb and The Paper was its location in the most conservative region of the country. In describing 1960s Mississippi, the paper’s founder wrote: “Most whites openly professed white supremacy, right-wing militaristic patriotism, and fundamentalist Christianity. They also had repressive, Victorian sexual attitudes and were oppressively anti-intellectual.”13

David Doggett was intimately familiar with the realities of his native state, having grown up in small Mississippi towns where his father had served as a Methodist minister. In 1964, Doggett entered Millsaps College in Jackson, a tiny liberal arts school, and promptly joined a fraternity, began dating a cheerleader, and started spending his free time in local jazz clubs.

In Doggett’s sophomore year, his life changed. Eager to become involved in both the Civil Rights and Counterculture Movements, Doggett replaced the fraternity, cheerleader, and jazz with active membership in the Southern Student Organizing Committee—SSOC was to the Deep South what Students for a Democratic Society was to the country as a whole.

Doggett then became the archetypal hippie; he grew a beard and shoulder-length hair, wore love beads and a peace medallion, and indulged in lots of sex and lots of drugs. After graduating in 1968, he worked as a full-time organizer for SSOC with a subsistence salary of fifteen dollars a week, deciding that his primary mission as a professional agitator would be to found a hippie paper in Jackson.

The Kudzu’s name referred to the tenacious vine that grows over old sheds, trees, and telephone poles throughout the South, with Doggett hoping his publication would spread in a similar fashion. An editorial titled “Generational Revolt” in the first issue described what Doggett saw as the scope of the youth rebellion. “We do not seek a narrow, violent, political revolution. We seek a much more profoound [sic] revolution, a revolution of a whole culture.”14

The paper functioned as a collective with no one on the staff having specific titles or responsibilities. The young volunteers lived in a small apartment that doubled as a newspaper office. Because The Kudzu was the only visible institution in the Deep South that advocated radicalism, the office soon became the center of the Counterculture Movement for that part of the country.

The paper appeared irregularly once or twice a month and varied dramatically in size—eight pages one issue, thirty the next. It carried few ads, and revenue from circulation, which peaked at 1,200, came nowhere near paying the printing costs. A handful of loyal supporters made sporadic financial contributions, all of them small, to keep the paper afloat. “If it hadn’t been for periodic donations from my parents,” Doggett later said, “I would have starved to death.”15

From its home in Jackson, Mississippi, The Kudzu provided a hippie voice from the Deep South.

The staff’s major nemesis was not money, however, but the local police. Outraged by The Kudzu’s very existence, officers arrested the dozen staff members when they attempted to sell copies of the first issue. When Doggett asked what the charges were, an officer picked him up and threw him into the back of the sheriff’s car. During the questioning that followed, Doggett and the other students were clubbed and kicked.16

That was the first of many encounters with police in which staff members were charged with obscenity, had their cameras and notes confiscated, and were evicted from a series of apartments. After each arrest—Doggett estimated the total reached at least forty—and subsequent round of beatings, the police would drop the charges. “After all, we weren’t doing anything illegal,” Doggett said. “We were just trying to publish a newspaper.”17

No easy task. “We worked sixteen hours a day,” Doggett recalled. “We finished the layout [on production days] at 5 o’clock in the morning, then piled in some clap-trap car or VW bus and rushed to New Orleans to make the printer’s 9 o’clock deadline.”18

Despite the many travails involving finances, police harassment, and long hours, the youthful staff members found creative ways to keep up their spirit. They added the names of their cats and dogs to the staff box published in the paper and turned their apartment/office into a safe house for runaway teenagers and other hippies passing through town. The staff also relaxed every Sunday by listening to rock music in a local park or retiring to the banks of the Pearl River. “We all stripped off our clothes and went swimming,” Doggett recalled fondly, “and sat nude around a campfire.”19

OBLITERATING SEXUAL TABOOS

A liberated attitude toward sex was a hallmark of the counterculture press, in both editorial and advertising content. The papers were determined to make America loosen up and enjoy the new freedoms that the 1960s offered through free love—defined as sexual activity of virtually any type with anyone, anytime, any gender, any number.

The Berkeley Barb set the standard. The paper’s major venue for sexual discourse was a first-of-its-kind medical advice column titled “Dr. HIPpocrates.” Berkeley physician Eugene Schoenfeld, who wrote the column, answered questions from readers not in arcane medical jargon but in street language—and often with his tongue firmly implanted in his cheek. Many young people across the country, in fact, bought the Barb solely to hear what Dr. HIPpocrates had to say, his information being equally relevant to people living in Berkeley, Boston, Baton Rouge, or, for that matter, Bangkok.

“Question: Can infectious hepatitis be contracted through cunnilingus? Answer: This is an excellent way—if the recipient of your affection has the disease.” “Question: Is it possible to get a venereal disease in the bathroom? Answer: It is certainly possible, but the floors are usually cold and hard. In other words, only in the very rarest of circumstances could one contract a venereal disease other than by direct and intimate physical contact with another person.”20

Hearing candid words from Dr. HIPpocrates was not the only reason that people with active libidos were buying the Barb. By the late 1960s, the tabloid was printing rivers of erotic classified ads. They offered plenty of intriguing adventures for men (“Groovy blond chick, semi-hip, seeks interesting male 30–40”) as well as women (“Two young males, 21–24, seek a nympho woman or girl to live in”), with a sprinkling of possibilities for gay men, too (“Gay guy, 26, seeks guy, 26–29, for sincere lasting relationship. Prefer a blonde”).21

Half a continent away, The Paper’s sexual content was only slightly more restrained. The Michigan paper illustrated one issue with six pages of erotic photos of nude couples engaging in foreplay and intercourse—the paper’s regular printer refused to print the photos, forcing the editors to scour the Midwest to find one who would. In the various essays wedged between the titillating images, The Paper called for “free birth control pills for all coeds” and for the elimination of all sexual taboos—“The more restrictive the moral codes of conduct, the less emotionally responsive the sexual practices will be.” Other bold statements included: “We are all searching for the Ultimate Orgasm. Why should we let petty considerations sway us from this grand desire?”22

The Kudzu’s location in the Deep South didn’t stop the hippie paper from joining the effort to liberate readers from their sexual hang-ups. Many of the messages were communicated through the personal advice column “Heavy Hog.” When an eighteen-year-old young woman wrote that she had a crush on a member of a local band and needed help dealing with her feelings of jealousy toward the musician’s other female fans, the columnist wrote that the young woman’s real problem was not jealousy—but fidelity. “Don’t get so hung-up on one guy,” came the response. “Groove with a bunch of them. Get naked and smoke. Come and go. Take a trip to Paradise and free your body and soul. You’ll be happier.”23

CELEBRATING RECREATIONAL DRUGS

As shown by the “Heavy Hog” response, the counterculture press saw the drug-induced psychedelic experience as an instant way to step outside the prevailing culture and look on society from an estranged perspective—the activity that was, after all, the central goal of the counterculture. Because of this benefit, using drugs was well worth the risk of being arrested and sent to jail.

Much of the Berkeley Barb’s coverage of drugs, like that of sexual topics, came from the oracular Dr. HIPpocrates. By providing factual responses to questions about the effects of various drugs, the popular doctor destroyed many of the myths that wafted through the American youth culture. “Question: I have heard that marijuana usage causes vitamin deficiencies. Can you tell me if this is so? Answer: There are no known harmful effects from the use of marijuana.” In addition to giving such straightforward answers, Dr. HIPpocrates was sometimes proactive, letting his readers know about new recreational drugs that had become available. “It is time that some straight information be given about the new hallucinogen STP,” he wrote in one column. “STP produces a 12 to 30 hour psychedelic experience similar to LSD.”24

The Paper’s pro-drug stance began with such supportive statements as: “The harm resulting from drug use, if any, affects only the user, and the government has no right to deny an individual his freedom of action if his action endangers no one but himself.” And then, in late 1969, The Paper took a huge proactive step by publishing information that helped drug users evade narcotics agents. In a feature story titled “NARCS,” the paper reported the name and physical description of an undercover agent who had succeeded in infiltrating the local hippie community to the point that she was responsible for several arrests. The article described how Barbara Bencsik was masquerading as a hippie but was, in fact, “the lowest form of animal life imaginagle [sic].” After The Paper identified Bencsik, local drug users avoided her, forcing police officials to reassign the woman who had been one of its most effective officers.25

Despite its location in the most conservative region of the country, The Kudzu also campaigned to liberalize drug laws. In a typical article, the paper asserted that “scientific evidence shows that marijuana is harmless both to the individual and to society.” The piece went on to accuse politicians of making the possession of marijuana illegal solely as a means of social control, rather than out of any concern for the well-being of the users. “It is a common practice for police or other law enforcement officials to use marijuana charges (real or trumped up) to jail radicals who prove to be a threat to the status quo.” The paper did not stop with abstractions but went on to accuse the local police in Fayetteville, Arkansas, of planting marijuana on several young people who had organized a Students for a Democratic Society chapter in that city. “These SDS members will have to spend a good bit of there [sic] time that could have been used for organizing in fighting the phony charges instead.”26

PROMOTING A REVOLUTION THROUGH ROCK ’N’ ROLL

In 1954, a nineteen-year-old musician from Mississippi named Elvis Presley compressed the red clay of the Pentecostal Church and the rhythms of Black America until they exploded to create rock ’n’ roll. A dozen years later when the Counterculture Movement was at full tilt, rock music had gained an urgency and a defiance that radiated a sense of what life could feel like if people would cast off their inhibitions. “Satisfaction,” “Purple Haze,” “Lucy in the Skies with Diamonds,” “Hey, Jude,” “Why Don’t We Do It in the Road,” “Happiness Is a Warm Gun,” “Street Fighting Man,” “Revolution”—they were all vinyl diary entries marking a listener’s first demonstration, first one-night stand, first trip, first brush with teargas, first night in jail.

Despite rock ’n’ roll’s evolution into a potent cultural force, the established media largely ignored it. When mainstream newspapers and magazines mentioned the new musical form at all, they did so with anthropological detachment; it was a passing fad worthy of no more than a one-time feature story written in the snide tone of superiority that the graybeards of American journalism reserved for articles about children.

So the emergence of rock ’n’ roll into a phenomenon of unparalleled cultural dimension was left to the counterculture press to chronicle. The Barb and its imitators, therefore, treated rock ’n’ roll as both music and an agent of change. The papers put rock at the journalistic center of the odyssey they were sharing with their readers, knowing that music had become the main touchstone for many young people who had become alienated from society. The Baby Boomers were taking over—first the music, then every other facet of American life.

The musical prophet for the counterculture generation was Bob Dylan. “He progresses and breaks ground for his fellow travellers,” one piece said. “There are times when you HAVE to listen to ‘Like a Rolling Stone’ and nights when you HAVE to hear ‘Sad-Eyed Lady [of the Lowlands]’ before you can stop your mind. There are moments when ‘Tambourine Man’ sifts to consciousness. That’s all there is.” The writer then made a valiant effort at articulating exactly why Dylan was the leading musician of the era. “When you listen closely to Dylan, you feel the words. It’s using words to appeal to the senses, not to the rational mind. You feel it through your eyes or ears or skin.”27

Among the decade’s numerous musical groups, the Beatles were the most important. Sensing the seismic influence that the British imports would have on the United States, a counterculture paper often devoted a page or more to reviewing the latest Beatles release. After Time and Newsweek had both pooh-poohed what became known as the legendary “White Album,” for example, The Kudzu published a song-by-song analysis. “The new double album is a difficult and complex work which deserves a great deal of careful consideration,” the piece began. The author was particularly taken with “Rocky Raccoon,” which music historians ultimately would identify as the epitome of John Lennon’s dark wit. “The theme seems to be confused identity crises and (I know you want to believe it) the need of modern man to see the paltriness of his life with a heroic vision, and his inability to do so. In the end the song turns in upon itself, becoming a bitterly farcical commentery [sic] on the human condition. Listen to this one yourself.”28

It didn’t take long for the music industry to realize that the counterculture press had developed an intimate relationship with a new generation of consumers. So the major record companies began pouring advertising money into the alternative papers. Typical was a two-page ad—it ran in the Barb, The Paper, and numerous other publications—that read “Underground … Overground. All that matters is that you dig the sound” above images of two dozen album covers from Columbia Records. Such ads were a major boon to the papers, most of which had been shoestring operations until the influx of ads from Columbia—the General Motors of the music industry—and other record companies.29

FIGHTING FOR SOCIAL JUSTICE

The lifestyle themes that were so pronounced in the counterculture press—it would be difficult to name three more tantalizing topics than sex, drugs, and rock ’n’ roll—should not obscure the demands for social justice that also played a prominent role in the various papers.

The emphasis the publications placed on ending the Vietnam War came bursting off the front page of the premier issue of the Berkeley Barb. The event at hand was a group of activists blocking a troop train that was transporting soldiers through Berkeley. The Barb expressed its sympathy with the demonstrators by reporting that GIs aboard the train supported the civilian protest. When the soldiers saw the demonstrators, the Barb said, they quickly hand lettered signs that they then pressed against the windows so the protesters could read them. “Keep up the good work. We’re with you,” read one; “I don’t want to go,” pleaded another. Mainstream newspapers that covered the demonstration made no mention of the signs.30

The Barb story also illustrated the paper’s commitment to local issues. Just below the lead story about the protest, the paper ran an article focusing on how the local police had physically abused the demonstrators. The Barb story began: “Thursday, August 12, 1965—a day of brutality in Berkeley,” reporting that the police had clubbed several protesters and had left one woman on the railroad tracks with a train approaching, adding that friends of the woman had to pull her to safety “at the last instant.”31

The paper’s intention to be proactive—it would not only report the news but also make events happen—was clear from the suggestive nature of the final paragraph of the police brutality story: “Two more troop trains are due in Berkeley next week. Suppose a thousand or more Berkleyans have a first hand look?” That activist orientation became a signature element of the paper’s highly interpretive approach to the news. When San Francisco police halted a peace march through the Haight-Ashbury district, the Barb made the event its lead story of the week, under the anti-police headline “Slug-Happy Cops Wreak Havoc in the Haight,” and when Los Angeles officers broke up a peace demonstration, the Barb shrieked “BLOOD PURGE! Cops Ambush LA Protesters.”32

The Paper’s anti-Vietnam War content also reflected that publication’s activist stripe, in this case a focus on Michigan State issues. Coverage that fit the bill perfectly evolved after Jim Thomas, a former MSU student then fighting in Vietnam, began sending poems and creative-writing pieces to The Paper. In one item, Thomas wrote: “Here we are aboard an assault ship bound to do battle against the powers of evil. We’ll hit the beach tomorrow. Time to practice being hard.” In early 1967, Thomas’s dispatches abruptly ended when the twenty-year-old corporal was killed in action. In a black-bordered tribute on page one, The Paper lamented: “America has lost a soldier, and America can afford that. But it has also lost a poet, and no nation can afford that.”33

Other editorial crusades waged in The Paper included trying to eliminate MSU’s Reserve Officer Training Corps and the National Merit Scholar program that had brought editor Michael Kindman to the university, and seeking to reduce the cost of textbooks by creating a student co-op. Kindman and his staff generally became involved in national issues of the Counterculture Movement only when there was a local angle; when two national SDS leaders came to campus, The Paper printed verbatim texts of their speeches.34

Although The Kudzu joined its counterculture press colleagues in opposing the Vietnam War, the paper’s major editorial thrust was to seek social, political, and economic equality for Americans of African descent. David Doggett, as both a hippie and a civil rights activist, was determined that the paper would advance the cause of black men and women, even though it was published in the depths of the segregated South. So when African Americans working for the city of Jackson—the only jobs open to blacks were as garbage collectors—formed their own union and attempted to secure collective bargaining rights, Doggett turned the effort into a major news story. After the City Council voted not to recognize the union, The Kudzu reported the defeat under the headline “City Dumps on Garbage Men” and threw its editorial support behind the black workers, writing that the action “left laborers with no vacation and no grievance prosedure [sic] when they were fired.”35

Doggett saturated his paper with articles about the myriad incidents throughout the South in which young African Americans were attempting to secure their civil rights. Typical was a story about 1,800 black high school students in Leland, Mississippi, boycotting classes to protest the poor quality of their education; the final sentence of the story pointed out that the school district had been cut off from federal funding because it refused to comply with court orders to desegregate. Other stories told of students at Mississippi’s Tougaloo College holding a mass teach-in to demand that black studies courses be added to the curriculum, and of students at Bluefield State College in West Virginia bombing a campus building to protest the lack of black cultural events on campus.36

FALLING VICTIM TO THE GOVERNMENT’S SECRET WAR

By late 1968, the counterculture press had become the central force in defining the dynamic youth rebellion. Editors were proudly calling their press, in the vernacular of the era, a “magic mushroom” that was exploding both in size and impact.37

The editors were not alone in recognizing the significance of their publications. On the very day that Richard Nixon was elected President, FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover sent a memo to his offices coast to coast. The subject of the communiqué was a plan Hoover had developed to halt what his lieutenants were characterizing, with considerable panic, as the “vast growth” of counterculture papers. Hoover ordered every agent in the country to begin an immediate “detailed survey concerning New Left-type publications being printed and circulated in your territories,” instructing the agents to send him detailed information on each paper’s staff, printer, and advertisers.38

That memo was the opening round in a Secret War the FBI and other federal and local agencies waged against the counterculture press. In an extension of the Counter Intelligence Program (COINTELPRO) that the FBI had launched against communism in the 1950s, Hoover told his agents to do whatever was necessary to force the papers to “fold and cease publication” and thereby eliminate what he considered the movement’s most important means of developing and spreading its anti-establishment ideology. That offensive—which would not come to light until more than a decade later when Freedom of Information Act requests forced the FBI to open its files to the public—included an alarming array of illegal activities.39

One way the FBI consistently broke the law was through forgery. Agents in Texas created phony letters in which they posed as parents complaining about how counterculture papers were harming their children, prompting university officials to prevent the papers from being distributed on their campuses; such letters resulted in outlawing The Rag at the University of Texas and Dallas Notes at Southern Methodist University, among others. Agents also falsified letters to University of Alabama administrators threatening to make life difficult for the school if it did not stop two instructors from donating money to a student paper—the two teachers were subsequently placed on probation.40

Obscenity laws gave the police a tool that appealed to citizens disturbed by the turbulent changes in America’s sexual mores. One nefarious campaign was against Miami Daily Planet editor Jerry Powers, who was arrested twenty-eight times on charges of selling obscene material. He was acquitted each time, but he still had to pay a phalanx of bail bondsmen $93,000. The Daily Planet’s experience was by no means unique. Although the counterculture papers generally won their obscenity battles, it often took years for judgments to be handed down. The expenses required for a publication to defend itself, therefore, meant that the financially vulnerable operations often did not survive. NOLA Express in New Orleans triumphed in two obscenity cases the government filed against it, and yet the paper was forced out of business because of the legal fees it had to pay its lawyers. Likewise, Open City in Los Angeles had to pay legal fees related to an obscenity conviction; the paper was later vindicated by a higher court, but, by that time, the lawyer bills had forced Open City to cease publication.41

Local police and politicians were also fond of using drug laws to silence counterculture papers. FBI and CIA agents—even though federal law prohibits the Central Intelligence Agency from conducting activities inside the United States, the agency was very active in the Secret War—increased the effectiveness of their drug raids by infiltrating the staffs so narcotics squads would know exactly when drugs were likely to be used, such as immediately after a weekly deadline had been met.

The very real threat of drug arrests created a state-of-siege atmosphere on many staffs. After the Daily Flash printed a series of articles critical of St. Louis Police Chief Walter Zinn, an undercover policeman was assigned to infiltrate the paper; a short time later, the officer arrested editor Peter Rothchild for possession of marijuana. When the entire staff of the Argus in Ann Arbor, Michigan, was arrested on drug charges, the paper immediately ceased publication. Perhaps the best-known drug case was that of John Sinclair, editor of Detroit’s Sun; arrested and tried solely on the testimony of two undercover narcotics agents who had infiltrated the staff, Sinclair was sentenced to ten years in prison for possessing two marijuana cigarettes.42

In some instances, the motivating factor for punishing a counterculture paper was pure revenge. When the Philadelphia Free Press published damaging information about Police Commissioner Frank Rizzo, he vowed to destroy the paper. During the next six months, police officers waged a relentless vendetta against Free Press staff members—physical assaults, searches of homes and offices without warrants, breaking into the locked cars of several staff members, opening the mail sent to and from the newspaper. The most disheartening event occurred when the mainstream Philadelphia Evening Bulletin published a major story on the Free Press that described staff members as “violent” and revealed confidential financial, family, and employment information about staff members—material that could only have come from Philadelphia police and FBI files. By the time Rizzo and his co-conspirators had finished with the counterculture paper, its long-time printer and numerous advertisers had abandoned it, forcing the paper to cease publication later that year.43

The most frightening of all the battles in the Secret War were those involving violence that was so severe that the perpetrating law enforcement officials could justifiably be labeled “domestic terrorists.” The office of the Washington Free Press in the nation’s capital was ransacked just before the 1969 presidential inauguration; four years later, the New York Times printed FBI documents proving that the raid had been the work of agents from the FBI and U.S. Army. Other FBI files now available link agents to firebombings of the offices of the Helix in Seattle, Space City in Houston, Orpheus in Phoenix, Great Speckled Bird in Atlanta, and Free Press in Los Angeles. The most sustained campaign of violence may have been against Milwaukee Kaleidoscope editor John Kois; his car was firebombed and shot at, and the windows in his newspaper office where he was working were shattered by gunfire.44

SPIRALING DOWNWARD

The rapid growth in the number of counterculture papers during the late 1960s was mirrored by a rapid decline in the early 1970s. Of the 500 papers being published in 1968, only forty still existed a decade later.45

That dramatic drop can be attributed to many factors. The gradual withdrawal of U.S. troops from Vietnam was one critical element, as were the inexperience, self-indulgence, political naiveté, heavy drug use, and fatigue of the youthful editors and staff members. But overwhelming these various factors was the Secret War by federal and local government agencies. Operating with pragmatic immorality, FBI agents and other law enforcement officials waged a take-no-prisoners assault on the counterculture press.

The Paper felt the impact of the Secret War primarily through its pocket book. After the university cut off the paper’s funding, it became almost entirely dependent on local and national advertising. That situation was fine—until the Secret War began. Michigan FBI agents targeted The Paper’s local advertisers by forging letters signed “Disgusted Patron” and sending them to East Lansing merchants, objecting to the counterculture paper’s often ribald content. Local advertising immediately plummeted. The even more serious attack involved the paper’s biggest advertisers: national record companies. In January 1969, a memo from the FBI’s San Francisco office to the headquarters in Washington asserted that Columbia Records “appears to be giving active aid and comfort to enemies of the United States” by advertising in counterculture publications such as The Paper. The memo went on to urge top FBI officials to use their high-level contacts to persuade Columbia and other major record companies to sever their relationships with the counterculture press. The double-page ads that had become the major source of income for the defiant Michigan weekly soon disappeared, followed by the one-page ads by smaller record companies.46

The Paper ceased publication in November 1969.

The Kudzu, as a hippie paper, never depended on advertising for its sustenance, relying instead on the youthful energy of its staff. So the secret warriors had to employ other tactics to take down the Mississippi paper. They were happy to do so, as the paper’s office was seen, and rightly so, as the hub of the Counterculture Movement in the Deep South and yet, despite relentless harassment by Jackson police for two years, the paper had continued to function. So in 1970 the FBI placed The Kudzu and its staff under intense surveillance. Agents began searching the office at least once each and every day—always without warrants—claiming to be looking for SDS leaders. On several occasions, the uninvited visitors threatened to kill certain staff members, and once they held eight of the young people at gunpoint for several hours. The FBI’s terrorizing tactics were highly effective in driving away the hippies who composed The Kudzu staff, as they were pacifists who had dropped out of the dominant culture to embrace a contemplative life of yoga and meditation—not guns and ammo.47

The Kudzu ceased publication in December 1972.

The Berkeley Barb survived far longer than most counterculture papers, but its destiny also was determined by the Secret War. The commercial paper that Max Scherr and his family depended on for their livelihood had, by 1969, grown into one of the largest dissident publications in the country, with a circulation approaching 100,000, editorial content that was less politically radical than that of The Paper or The Kudzu, and an abundance of the one- and two-page ads that the country’s leading record companies were eager to place in a paper that circulated heavily among University of California students. When the titans of the music industry pulled their ads, therefore, Scherr was desperate to find a new source of revenue. He struck the mother lode through classified sex ads, with the ads soon filling as many as fifteen of his twenty-eight weekly pages. The ads gradually shifted from the statements of sexual freedom they originally had been, however, to blatant pornography—such as “Outcall services to your hotel or motel in Eastbay area” and “Lovie Craves It is back and showing her beaver up close to gents”—that was in total conflict with the Women’s Liberation Movement that had emerged alongside of the Counterculture Movement. Ads for prostitutes and massage parlors were not sexually liberating; they perpetuated the oppressive concept of women being sex objects who could be bought and sold as a commodity. By the mid-1970s, the Barb was known not as a counterculture paper but as a vulgar and sexist one.48

The Berkeley Barb ceased publication in July 1980.

CREATING A GOLDEN AGE OF AMERICAN YOUTH

Like many genres of the dissident press, the counterculture papers did not have a lengthy lifespan, with most of the publications surviving no more than half a decade. Despite its brief history, however, the printed voice of the Counterculture Movement retains a certain “magic” that many other forms of the dissident press do not. When today’s college students are asked to name an example of non-mainstream journalism, the most frequent response is a reference to those rag-tag, wild-and-woolly, highly personalized publications that spoke for that golden age in the history of American youth: The Sixties.

Further evidence of the unique stature of counterculture papers comes from noting the large quantity of material that has been written about this particular genre of the dissident press. Scholars have paid scant attention to many alternative journalistic endeavors that have sought to change society—no books have been written about the nineteenth-century sexual reform press, the anarchist press, or the birth control press. Scholars have, by contrast, published half a dozen books specifically about the 1960s counterculture press.49

But this press is of historical significance for more reasons than the interest it generates among students and scholars. Looking at the major themes that dominated this genre of journalistic dissidence shows that it ultimately had enormous impact on society. The publications certainly succeeded in helping America become more liberated about sexual activities and recreational drugs—although it can be debated whether the country is better for it. Likewise, the counterculture press played a singular role in legitimizing rock ’n’ roll; after publications such as the Berkeley Barb and The Kudzu began writing about this new musical genre in the mid-1960s, such middle-of-the-road publications as Time and Newsweek added, by the early 1970s, rock ’n’ roll columns. And with regard to social justice, the counterculture press clearly helped the anti-war press hasten the end of the Vietnam War, assisted in expanding the Civil Rights Movement to college campuses, and became a catalyst for many of the rights now enjoyed by American college students—such as university curricula being shaped by student demands and university policy-setting boards and committees no longer being considered complete without student representation.50

Acknowledging the impressive legacy that the short-lived counterculture press left in its wake begs a “what if” question that can be asked as the final thought about this category of the dissident press: What might the Berkeley Barb, The Paper, The Kudzu, and the hundreds of newspapers like them have been able to accomplish if the nation’s law enforcement officials had not harassed, intimidated, and beaten the staff members or committed acts of domestic terrorism—such as ransacking and fire-bombing the offices of this memorable generation of committed and high-spirited journalists?