The Black Panther newspaper is credited with establishing “pig” as a derogatory synonym for “policeman”—both in print and in visual depictions.

Although J. Edgar Hoover and his agents-turned-domestic-terrorists disliked every aspect of the Counterculture Movement, at the very top of their list were the Black Panthers. Like many white Americans, the FBI director and his lieutenants saw the young black men—with their leather jackets and military berets, their clenched jaws and the guns gripped tight in their fists as they marched defiantly through city streets—as the most dangerous element in society, destined to destroy everything that was good about America. The Panthers represented “the greatest threat to the internal security of the country,” Hoover said in 1969, and directed his men to do everything humanly possible, both legal and illegal, to “destroy” them.1

In the minds of very few people living in the 1960s or the decades that followed, on the other hand, did mention of the words “Black Panthers” evoke the image of a cluster of passionate, forward-thinking young journalists bending over their typewriters into the wee hours of the morning to articulate a political ideology that would guide Black America into the new millennium.

And yet, the same militant activists who led the Black Panther Party into legendary status as one of the most fearsome organizations in the history of the United States, in fact, also produced a weekly newspaper that developed a remarkably far-reaching vision for Americans of African descent. Indeed, many of the concepts introduced in the pages of the Black Panther newspaper continue to reverberate through this nation today.

During the paper’s initial four years, from 1967 to 1971 when the party was at its peak, the editorial content was dominated by five major topics: police brutality, violence as self-defense, economics as the most serious form of oppression, Black American genocide by the federal government, and the need to resurrect black manhood. The enduring quality of these themes and the power and poignancy with which they were originally articulated combine to document that the racial activists who wrote for the paper—most notably Huey P. Newton, Bobby Seale, Eldridge Cleaver, David Hilliard, and Fred Hampton—were accomplished and far-sighted dissident journalists.

Because of the strength, insight, and pure effrontery of the editorial content of the Black Panther, it exploded into the largest African American newspaper in the country, with its 100,000 weekly circulation surpassing that of any of its competitors threefold. The paper was a truly grassroots publishing endeavor that provided a venue in which even the most powerless members of an oppressed minority found a voice. It is not surprising, then, that a publication with such a huge reach and vast potential to effect social change also soon attracted the wrath of the FBI and its Secret War.2

RAISING A REVOLUTIONARY VOICE

Huey P. Newton and Bobby Seale created the Black Panther Party in Oakland, California, in the fall of 1966 because, as Newton wrote at the time, “We want freedom. We want power to determine the destiny of our Black Community.”3

The two young men—Newton was twenty-four, Seale twenty-nine—belonged to families that had migrated west during World War II in search of jobs in the naval shipyards and munitions factories that had flowered on the West Coast during the country’s wartime build-up. While the families successfully escaped the rigid segregation of the South, however, they still suffered discrimination in employment, housing, and education—forces that thrust the Newton and Seale families into poverty.

Young Huey and Bobby both spent their childhoods in Oakland and met while studying at Merritt College. Taking advantage of one of the victories achieved by the counterculture press, the two young men joined forces and succeeded in having classes in black history added to the curriculum. Encouraged by their campus victory, they next set out to improve life in Oakland’s black ghettos. They began by knocking on doors and asking what the residents felt they needed most in order to improve the quality of their lives. Then Newton and Seale translated those answers into the programs at the center of the Black Panther Party—free health clinics, free breakfasts for school children, and free workshops in the political process.

But it was another of the party’s community-based activities that caught the attention of the public: armed patrol cars.

Newton, Seale, and the other young African American men they recruited into the party would climb into their cars—a gun in one hand, a law book in the other—and trail police cruisers around Oakland. So whenever police stopped black suspects, the armed Panthers made sure the officers did not violate the constitutional rights of the men and women they detained. The police were outraged that armed black men had the audacity to monitor them, even though it was fully legal for Californians to carry loaded guns, as long as the weapons were not concealed. The African American community had a very different reaction; blacks were impressed that the young men were committing their time and energy to protecting the rights of their fellow citizens. Even more important, the harassment and brutality that the Oakland police previously had directed against black men and women began to decline.

The white power structure, however, was less concerned about the ill treatment of black citizens than about armed black men cruising the streets of Oakland—a sight that most white people found terrifying. So in early 1967, a white East Bay legislator drafted a bill that would disarm the Panthers by making it illegal to carry a loaded gun in public, whether concealed or not. When twenty Panthers stormed into a chamber of the California Assembly brandishing loaded rifles, pistols, and shotguns to protest the proposed legislation, newspapers across the country captured the moment in photos—and the Black Panthers were instantly known nationwide. Although the black activists failed to block the bill, the publicity boosted party membership—virtually overnight—to more than 10,000.4

The catalyst for founding a Panther newspaper was a local incident that took place in early April 1967. According to the report filed by a white deputy sheriff of the Richmond, California, police department, when the officer tried to arrest Denzil Dowell on suspicion of stealing a car, the young man fled. The deputy sheriff then shot and killed the black twenty-two-year-old, and the authorities ruled the death justifiable homicide. Dowell’s family charged, however, that the officer had threatened to kill Dowell long before the incident. When the mainstream news media failed to give the case the attention that Newton and Seale thought it deserved, they started their own paper.

The premier issue of the Black Panther appeared in late April 1967 as two mimeographed sheets stapled together and distributed to some 3,000 residents of Oakland’s black neighborhoods. The weekly paper quickly expanded to twenty-four tabloid pages and its circulation increased manyfold, sold nationwide for twenty-five cents via the network of local Black Panther Party chapters that had erupted in thirty cities.

The Panther’s editorial content was dominated by strident essays insisting that African Americans would never secure true freedom unless they waged a social and political revolution. References to the United States being a fascist nation were frequent, as were shrill demands for drastic change. “People are not going for all the bullshit America preaches,” one article screamed. “Oppressed peoples are forming a proletarian force that will rise and crush the pig power structure. All Power to the People!!” In another essay, Newton wrote, “The only way that we’re going to be free is to wipe out once and for all the oppressive structure of America.”5

News stories also fulfilled a crucial function. For the Panther was often the only source of information about events occurring in America’s black communities that were being ignored by the establishment press. When African American high school students in High Point, North Carolina, went politely through the proper channels to request that the local school board add black studies to the curriculum but then were summarily suspended, the story appeared in the Panther; the mainstream press did not report the incident. Likewise, when Los Angeles police responded to a white landlord’s complaint against his black women tenants operating a day care center in his building by herding the teachers and children onto the lawn and holding them at gunpoint, the Panther reported the story in all its bizarre detail; the mainstream press did no so much as mention it.6

These and hundreds of other news articles were written by people who were not official members either of the Panther staff or the party. But by printing the stories, the paper gave poor and politically dispossessed African Americans a venue for community news they had never had before. Bobby Seale said that giving common people a voice was one of the Panther’s most significant contributions because the stories “come from the hard core of the black community, the grassroots.” Fred Hampton, chairman of the party’s Illinois chapter and a contributor to the paper, made the point in more colorful terms: “If you don’t read the Black Panther paper, fuck it right there—you ain’t read shit.”7

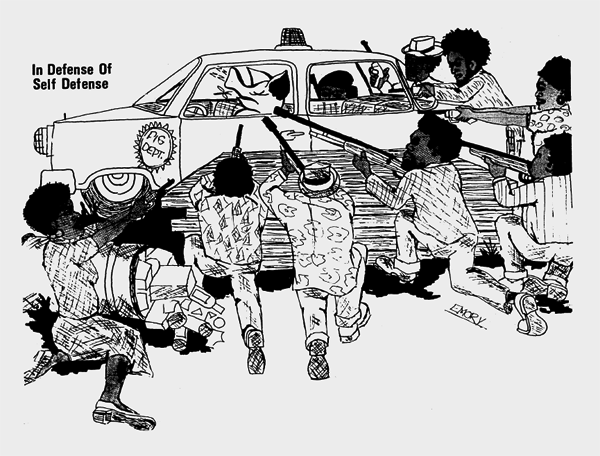

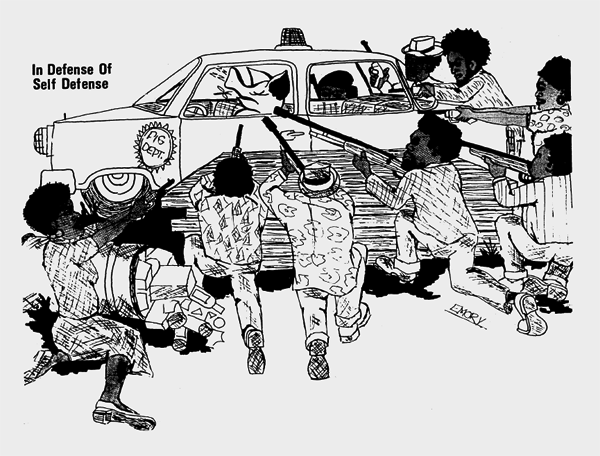

Artwork was integral to the editorial mix. Images of pistols, shotguns, machine guns, hand grenades, and clenched fists dotted every issue. Among the other compelling graphics were dozens of cartoons featuring pigs dressed in police uniforms. Some of them depicted the officers as inept and foolish—one showed a cluster of pigs in police uniforms firing pistols into the air while dancing and swigging down alcohol, another had a pig sleeping in the driver’s seat of his police car as black youths surrounded the vehicle and aimed their weapons at the hapless officer’s head. Other of the images were even more sinister. One showed an angry black man preparing to thrust a huge knife into a crying pig/policeman; another depicted a black man holding a shotgun that he had just used to kill the pig/policeman lying lifeless at his feet.8

The Black Panther newspaper is credited with establishing “pig” as a derogatory synonym for “policeman”—both in print and in visual depictions.

Absent from the Panther’s pages were the mainstay of establishment journalism: advertisements. No major businesses were willing to be associated with the paper’s militant ideology—no matter how large the circulation—and very few of the small, black-owned enterprises in sympathy with the Panther could afford to buy ads. So the dissident journalists depended on circulation revenue to pay their printing and mailing costs. Sales grew so rapidly in the late 1960s that profits from the paper were used to support the party’s other activities, such as the health clinics and breakfasts for school children. The Panthers who wrote, edited, and distributed the paper received no payment.

Eldridge Cleaver served as the Panther’s first editor, but Huey P. Newton emerged as the strongest and most articulate voice. Newton’s image was a strong visual presence in the paper as well; photos of the handsome mulatto man—tall, muscular, and unsmiling in black leather jacket and beret, with a pump shotgun and bandolier of shells strapped across his chest—often filled an entire page. Men dominated the top positions on the paper, as they did in the party, with women largely confined to typing stories and laying out the pages.

The Black Panther rejected the strict language requirements observed by conventional American journalism. The paper has been credited with originating the term “pig” as a derogatory synonym for “policeman,” and the slogan “Off the Pigs!” was sprinkled with regularity throughout the paper. Expletives such as “shit,” “fuck,” and “motherfucker” appeared frequently as well. Seale wrote, “The language of the ghetto is a language of its own, and as the party—whose members for the most part come from the ghetto—seeks to talk to the people, it must speak the people’s language.”9

STOPPING POLICE BRUTALITY

The prominent role that police brutality would play in the editorial content of the Black Panther became clear in how the Denzil Dowell incident dominated the first issue. A large photo of the young man ran under the headline “Why Was Denzil Dowell Killed?” Sharing page one was a boxed statement that announced a community meeting about the Dowell shooting and ended by saying, “Every black brother must unite for real political action.” The rest of the issue was filled with a list of unanswered questions related to the killing and an essay raging against rampant police brutality.10

The essay provided a preview of the battery-acid prose style that would become a hallmark of the militant paper. “In the past, Black People have been at the mercy of cops who feel that their badges are a license to shoot, maim, and out-right murder any black man, woman, or child who crosses their gun-sights,” the essay read. “But there are now strong Black men and women on the scene who are willing to step out front and do what is necessary to bring peace, security, and justice to a people who have been denied all of these for four hundred years. The Black Panther Party takes action.”11

In later issues, Newton argued that only police officers who had been raised in the black ghetto should be allowed to patrol there. When law enforcement officials sent white police into black neighborhoods, he wrote, they could be compared to the United States sending its “occupying army” of American soldiers into Vietnam. “The racist dog policemen must withdraw immediately from our communities, cease their wanton murder and brutality and torture of black people,” Newton wrote, “or face the wrath of the armed people.” In another essay, he articulated exactly how that rage would be manifested. First arguing that the peaceful demonstrations used in the Civil Rights Movement were ineffective and should be replaced by “guerrilla methods,” Newton went on to endorse the murder of racist police officers. “When the masses hear that a gestapo policeman has been executed while sipping coffee at a counter,” he wrote, “the masses will see the validity of this type of approach.”12

Editorial efforts to stop police brutality extended beyond angry essays. Residents of black neighborhoods across the country contributed a steady stream of fact-based news stories reporting instances of African Americans being mistreated by officers in Chicago and Detroit, Boston and Philadelphia, New Haven and Winston-Salem. Many of the stories were illustrated by drawings that showed pigs dressed in police uniforms as they beat, tortured, and humiliated helpless black men and women. Eldridge Cleaver wrote of the paper’s ubiquitous symbol of police brutality: “A dead pig is the most desirable, but a paralyzed pig is preferable to a mobile pig.”13

EMBRACING SELF-DEFENSE CUM VIOLENCE

As illustrated by Newton’s and Cleaver’s open advocacy of killing racist police officers, the Black Panther did not embrace the nonviolent credo that was central to the Civil Rights Movement of the 1950s and 1960s. While the movement’s Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. unequivocally opposed violence, Panther leaders opted for the approach that their fellow dissident journalist Ida B. Wells had pioneered the previous century and that their contemporary Black Power leader Malcolm X revived when he insisted that blacks should secure freedom “by any means necessary.” Like the Black Power leader, the militant men who led the party believed that the nonviolent tactics used in the rural South would be ineffective in the urban North. The Panthers often quoted Malcolm X’s mantra: “The time has come to fight back in self-defense whenever and wherever the black man is being unjustly and unlawfully attacked. If the government thinks I am wrong for saying this, then let the government start doing its job.”14

The important role that self-defense would play in the Black Panther Party was immediately evident when Newton and Seale selected a name for their organization. They chose the panther as their namesake because, Seale said, “It is not in the panther’s nature to attack anyone first. But when he is attacked and backed into a corner, he will respond viciously and wipe out the aggressor.” A drawing of a panther, with its claws extended and teeth bared, appeared on the top of page one of the Black Panther each week, and additional drawings of the fierce animal appeared on inside pages as well.15

Various writers reinforced the importance of African Americans defending themselves. Newton wrote, “Black people can develop Self-Defense Power by arming themselves from house to house, block to block, and community to community throughout the nation.” David Hilliard upped the level of militancy by insisting that self-defense extended to killing the enemy, including police officers: “We only advocate killing those that kill us. And if we designate our enemy as pigs, then it would be justified to kill them.” Eldridge Cleaver echoed the same point—with an equal dose of defiance—by speaking directly to White America: “From now on, when you murder a black person in this Babylon of Babylons, you may as well give it up because we will get your ass. Black people, this day, this time, say halt in the name of humanity!”16

The most vehement endorsements of self-defense published in the Panther were tantamount to calls for violence. In a 1969 essay, David Hilliard singled out President Nixon as the man ultimately responsible for Black America’s oppression. Hilliard’s tone grew angrier and angrier as the essay progressed, and his final words sounded like those of a warrior poised to attack his enemy: “We will kill Richard Nixon. We will kill any motherfucker that stands in the way of our freedom. We ain’t here for no goddamned peace, because we know that we can’t have no peace because this country was built on war. And if you want peace you got to fight for it. All Power to the People.”17

COMBATING ECONOMIC OPPRESSION

While the Black Panther’s essays raging against police brutality and promoting violence as a form of self-defense stirred the most public attention, essays on those topics were, in reality, far fewer in number than editorial statements that focused on economic oppression as the root problem facing African Americans. Every issue of the paper included at least one lengthy treatise focusing on economics.

The specific economic theme discussed most frequently was Huey P. Newton’s demand that White America provide financial reparations to Black America for the debt that had been created by the institution of slavery. The cofounder of the party argued that the heinous practice of human bondage had doomed African Americans to their current subservient social, economic, and political position, and, therefore, the government should right that wrong by directing massive tax revenue into poor black neighborhoods. “The racist government has robbed us, and now we are demanding the overdue debt,” Newton wrote. “We will accept the payment in currency which will be distributed to our many communities. We feel that this is a modest demand.”18

Other writers echoed Newton’s call. “We want land, bread, housing, education, clothing, justice, and peace,” Seale began one manifesto. “The exploited, laboring masses and poor, oppressed peoples throughout the world want and need these demands for basic human survival.” Seale labeled the economic oppression against African Americans “domestic imperialism,” which he defined as “black people being corralled in wretched ghettos.”19

Many of the editorial cartoons published in the Black Panther newspaper celebrated African-American men who committed violent acts against racist law enforcement officers.

Economic repression was one of the few topics that women were allowed to write about. Connie Matthews focused on how the technological advances of an industrialized nation threatened black Americans. “Most of you will become redundant,” she told Panther readers. “You in the middle, who think you have something, who have those bills and those $20,000 houses, you are the ones who are going to find out that the mortgage you are going to have to pay back is about twice what you thought originally. Get yourself hip to all this, get with it and educate your people because the Black Panther Party is out there in the front but we can’t stay out there in the front forever. We will stay until everyone of us is killed or imprisoned by the racist pigs, but then someone will have to take over. So don’t let us all die in vain. Power to the People.”20

PREVENTING BLACK AMERICAN GENOCIDE

When Newton and Seale canvassed Oakland’s black neighborhoods, providing health care emerged as a top priority for the Panthers, with local chapters founding free clinics in such far-flung cities as Kansas City and Boston, Seattle and Brooklyn, Houston and Chicago. The health-care initiative gained even more momentum after the party’s dissident newspaper began a full-throttle assault on a medical crisis of such enormous dimension that it threatened to destroy Black America.

A black doctor launched the campaign against sickle cell anemia with a page-one article explaining the origins of the deadly disease. To develop immunity to malaria, Dr. Tolbert Small wrote, the bodies of people living in Africa centuries ago transformed their red blood cells from the original donut shape into a form resembling a sickle. But medical complications arose, he explained, when the men and women were captured by slave traders and transported to the United States where the modified cells proved to be a disadvantage in the new environment, resulting in sickle cell anemia.21

The disease—ninety-eight percent of American victims were black—blocked blood vessels and damaged numerous body organs, so victims suffered wracking pain in their joints, stomach, chest, and head. People afflicted with the disease also were highly vulnerable to infection and developed various brain and lung ailments, often dying before they reached the age of thirty.22

Although there was no known cure for sickle cell anemia, the doctor continued, it was possible to reduce the incidence of such a hereditary disease. Individuals carrying the trait—one in every twelve Americans of African descent—often exhibited no signs of the disease and could lead normal lives, Dr. Small wrote, but if a male and female carrier had children, there was one chance in four that those offspring would develop the full-blown disease.23

Dr. Small concluded by stating that testing and warning people that they were carriers would dramatically reduce the number of cases, and yet the U.S. government had not initiated a testing program. “Sickle cell anemia kills as often as muscular dystrophy or cystic fibrosis,” he reported. “Yet it has received little public attention and none of the large scale government funding that those other two diseases have, both of which usually affect White victims.”24

The editorial note accompanying the doctor’s article made that same final point; it was not written in the same calm tone, however, but in the highly volatile one that characterized so much of the Black Panther’s content. “Black People are being eliminated in such great numbers,” the note bluntly stated, “that the only conclusion that can be drawn is that a concentrated, malicious plan of genocide is being enacted upon us.”25

That blockbuster article and editorial note were the opening salvo in the Panther’s campaign to alert Black America of the medical danger lurking in its midst. “As a people, we must become conscious of this genocidal plan and its many faces,” read a typical piece, “so that we can fight the hard, long struggle—we must survive. If we do not become aware of the situation, we will be duped into the death of our entire People. Power to the People.”26

The Panther also demanded that research to find a cure for the disease be increased. During 1970, the paper reported, the number of new cases of sickle cell anemia surpassed 1,600, compared to 1,200 new cases of cystic fibrosis and 800 of muscular dystrophy. Yet the government had committed only $100,000 to sickle cell research, compared to $7.9 million and $1.9 million for the other two diseases. “This racist government has no intention of ceasing the genocide,” the paper raged. “Research on sickle cell anemia would hinder their plan of Genocide upon Black people.”27

The most important aspect of the Black Panther Party’s effort to eradicate sickle cell anemia—both through its newspaper and its network of free clinics—was that the campaign was accompanied by such compelling logic that the public health establishment could not ignore it. And after the American medical community took up the cause, Congress finally passed, in 1972, the National Sickle Cell Anemia Control Act, adopting the exact same priorities that the Panthers had called for years earlier—testing, warning, and funding research for a cure. Although there is no way to determine exactly how many lives and how much human suffering the Panther campaign saved, there is no question that they were substantial.

RESURRECTING BLACK MANHOOD

While slavery had been a devastating experience for African Americans of both sexes, the Black Panther believed that the abhorrent institution had its most long-lasting effects on black men because they had been denied the position of power and respect that white men traditionally held in relation to white women. Further, this reduced status was exacerbated by the economic deprivation that continued to define the Black American experience throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. In Huey P. Newton’s words: “The Black man feels that he is something less than a man. Often his wife (who is able to secure a job as a maid, cleaning for White people) is the breadwinner. He is, therefore, viewed as quite worthless by his wife and children. He is ineffectual both in and out of the home. Society will not acknowledge him as a man.”28

The Black Panther, therefore, crusaded to resurrect black manhood to a position of respect and power in the African American as well as the white community.

Although an occasional article made reference to women being part of the revolutionary force that was standing tall against racial oppression, the vast majority of the paper’s editorial content made it clear that men—and men only—should be at the vanguard. Newton wrote the seminal statement on the subject when he said that it was essential for the black man to “recapture his mind, recapture his balls. The Black Panther Party along with all revolutionary Black groups have regained our mind and our manhood.”29

Rank-and-file members of the party often communicated the Panther’s position on the need to reclaim black manhood not by praising men but by demeaning women. Typical of the writers was an unnamed man who criticized African American women as uniformly “selfish” and imbued with a misplaced “feeling of superiority.” The article went on to blame the endemic lack of stability in African American families on the black woman: “To a great extent, her attitude explains the high rate of divorce among Panthers and other revolutionaries.” Other articles reiterated the proper—and limited—role for black women; one stated point blank: “It is what the Black woman can contribute to the Black man that is important.”30

Male voices were not alone in placing tight restrictions on black womanhood, as numerous female writers in the Panther also defined the feminine role as one limited to supporting her masculine superior. A woman “must be the Black Man’s everything,” wrote one woman. “She must be what her man needs her to be.” The writer went on to urge her fellow “Pantherettes” to be “warm, feminine, loving, and kind”—characteristics far different from those applauded in male revolutionaries—and to devote the bulk of their time to the domestic duties that would provide their men with a safe and calm haven at home.31

The African American woman playing a central part in resurrecting black manhood by adopting the traditional female role of nurturer and supporter came through even more clearly in an article titled “A Black Woman’s Thoughts.” The author began by asking the rhetorical question: “What is a Black woman’s chief function, if it is not to live for her man?” She then continued by criticizing the white-dominated Women’s Liberation Movement of the era, insisting, “Black women must drop the White ways of trying to be equal to the Black man. The woman’s place is to stand behind the Black man.” Later in the piece, the author made the same blunt assertion by telling her African American sisters: “Stop playing the role of a man.”32

SILENCING THE DISSENTERS

FBI documents show that J. Edgar Hoover’s illegal activities against the counterculture press extended to the Black Panther. Indeed, it was against the militant African American paper that Hoover’s assault on the dissident press reached its most frightening level. Four months after the paper was founded, Hoover directed his field offices to “disrupt, misdirect, discredit, or otherwise neutralize the activities” of the staff. FBI memos that were made public through Freedom of Information Act requests show that, in response to the director’s order, agents placed wiretaps on the telephones at the paper’s office, strong-armed the man who distributed the Panther to triple the fees he charged the paper, and planted informants on the staff to provoke internal dissension.33

Staff members suspected, but could not prove, that the FBI also was behind a series of catastrophes that seemed more than coincidental: A warehouse filled with back issues burned to the ground. The Panther’s circulation manager in Southern California, Walter Pope, and then the national circulation manager, Sam Napier, were both murdered.34

Another instance involved much more than suspicion, as the American legal system ultimately ruled that the FBI and the Chicago police had conspired to murder Fred Hampton, who wrote for the paper. The FBI considered the nineteen-year-old Hampton a rising power figure in the party. So agents hired a petty criminal to infiltrate the Chicago operation; in exchange for information, law enforcement officers dropped auto theft charges pending against the man and gave him a monthly salary. The informant then became one of Hampton’s assistants so he could provide the FBI with detailed descriptions of the charismatic leader’s activities, including the specific firearms that were in his home. In December 1969, Chicago police obtained a warrant to search Hampton’s apartment for illegal weapons. Fourteen officers burst through the front door in the middle of the night and fired forty-two rounds from a submachinegun into the bed where Hampton was sleeping.35

Although the law enforcement officials killed Fred Hampton, they were less successful against his mother, who filed a civil lawsuit against the local state’s attorney who had orchestrated the raid—Hoover was also named as a co-conspirator. After a series of trials and appeals that extended for fourteen years, Iberia Hampton ultimately triumphed when a judge awarded her $1.85 million and ruled that there had, indeed, been a governmental conspiracy to deny her son his civil rights.36

Fred Hampton was by no means the FBI’s only target. By 1970, agents had succeeded in having more than 700 Panthers arrested, thereby forcing the party to spend upwards of $5 million and much of its energy not agitating for racial equality but defending its beleaguered members.37

A mind-numbing series of arrests, trials, convictions, imprisonments, mistrials, overturned convictions, escapes to foreign countries, and violent deaths took a devastating toll on the paper and the party. In October 1967, Newton was arrested and charged with killing an Oakland police officer, leading to the Panther’s most ardent voice being jailed and tried—and making “Free Huey!” a pervasive plea in the paper. In September 1968, Newton was convicted of manslaughter, but in August 1970 the conviction was overturned and Newton was released. In April 1968, party treasurer Bobby Hutton was shot to death as he attempted to surrender to Oakland police; Eldridge Cleaver and David Hilliard were among seven Panthers who were then arrested on murder charges in connection with Hutton’s death. Cleaver, who already had spent time in prison and refüsed to be jailed again, fled to Cuba and then Algeria. In May 1969, Seale was charged with killing party member Alex Rackley (Seale suspected Rackley of being an FBI informer); Seale spent two years in prison until a mistrial was declared. Also in 1969, Seale was sentenced to four years in prison for contempt of court because he had disrupted his trial on charges of conspiracy to incite a riot during the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago—Seale and other defendants became known as the “Chicago Eight.” Meanwhile, Hilliard was indicted for threatening President Nixon during a rally in Chicago—the same threat he made in the Panther. In 1974, police charged Newton with killing a prostitute, prompting the Panther leader to flee to Cuba. When Newton returned to the United States three years later, he withstood three costly trials before charges were finally dropped.38

By 1971, the FBI’s strategy had succeeded, and the Black Panther Party had been reduced to a shell of its former self. And as the party diminished in strength, so did its journalistic voice. The editorship changed hands many times, and essays crafted by such dynamic leaders as Newton and Cleaver appeared only rarely. During the 1970s, the Panther included little of the editorial fire that had defined its early years. The weekly was reduced to a bi-weekly in the late 1970s and then a monthly in early 1980. It ceased publication in October 1980.

DISGRACING THE CAUSE?

At the same time that the Black Panther was speaking up on behalf of oppressed Americans of African descent, the Black Panther Party was rapidly gaining the negative reputation that ultimately would come to dominate White America’s perception of it. With a loose structure that allowed considerable autonomy to local chapters as well as to individual members, there is no question that men affiliated with the party committed an untold number of abusive acts and inexcusable crimes. It is impossible, however, to know how many of the incidents were undertaken by Panthers of their own free will and how many were either instigated or fabricated by the FBI and its Secret War.

Drug abuse was one pervasive problem, as numerous members of the party—including Newton—became so dependent on cocaine that their lives reeled out of control; some members turned to drug dealing to support their habits. Sexual abuse was a concern, too, with party members taking their efforts to resurrect black manhood to extremes by raping and otherwise assaulting white as well as black women. Another disturbing activity involved rogue Panthers threatening and extorting money from struggling African American business owners, sometimes beating or maiming the very men and women they purported to be protecting. The long list of criminal acts attributed to the black revolutionary thugs is shocking, with the items ranging from harassment, robbery, and embezzlement to arson, prostitution, and murder.39

When the various negatives aspects of the African American revolutionaries were added together, according to some critics, the Panthers did far more to harm Black America than to help it. The author of a book devoted entirely to criticizing the party—titled The Black Panther Menace: America’s Neo-Nazis—wrote, “The Black Panthers are, in fact, the worst enemy the black man has in America—on a par with his implacable, ignorant, bigoted foes in the Southern United States.”40

A LASTING LEGACY

The Black Panther charted a unique journalistic course. By transforming the angry messages of black revolutionary icons into printed words, the newspaper performed a singular service for the Black Panther Party, as well as for Black America writ large. This dissident voice discussed topics that the American news establishment considered inimical to the well-being of the country. The impressive size of the audience that the Panther reached—100,000 at its peak—speaks to the eagerness with which readers embraced the paper’s ideology.

Dwarfing the role that the Black Panther played during its years of publication, however, is the impact that the paper’s editorial content has had since that time. For the primary themes raised in the pages of that revolutionary journalistic voice did not disappear when the paper ceased publication. Indeed, the issues that dominated the Panther’s pages still play important roles in the sociopolitical movement that continues to seek racial equality in this country today.

The most concrete example is the pig becoming a symbol for police officers. The Panther was the first publication to use this derogatory reference, in written form through editorials and graphic form through cartoons that depicted pigs wearing police uniforms—one of the newspaper’s signature elements. This symbol was immediately embraced by the Counterculture Movement and then gradually became an accepted entry in the mainstream vocabulary as well.

Another powerful concept that grew its roots in the pages of the Panther was Huey P. Newton’s demand that the U.S. government make restitution to African Americans for the sins of slavery by committing large quantities of tax money to poverty-stricken black neighborhoods. Although such proposed compensation was scoffed at by all but a handful of radical Americans in the late 1960s and is still far from becoming official public policy, the exact same proposal as the one articulated in the Panther has been debated in the halls of the U.S. Congress every year for more than a decade.41

The subjects of various other Panther essays are also still very much alive. The enormous public response to the videotaped beating of Rodney King by Los Angeles policemen in 1991 and the massive riots that were sparked by the acquittal of those officers are vivid reminders that police brutality remains a salient racial issue in this country. Likewise, the economic disparity between black Americans and white Americans—the median income of a black family is less than sixty percent of that of a white family—provides dramatic evidence that economic oppression of African Americans is another major problem. Although this country’s medical community eventually responded to the sickle cell anemia crisis by initiating a testing program, the disease is still a concern of major dimension in Black America. Finally, resurrecting African American manhood from its historic struggle for respect and dignity remains a concern, as demonstrated by the efforts of 1995’s Million Man March in Washington, D.C.42

A primary reason why the concepts that were communicated in the pages of the Black Panther did not fade from the American consciousness is that, when the newsprint began to yellow, the original essays and artwork were preserved in other forms. The activities of the Black Panther Party took on legendary proportions, historians theorize, because they represented the first nationwide black political phenomenon—as distinguished from religion-based undertakings such as the Civil Rights Movement—that stood tall and stood firm, the party leadership unequivocally and steadfastly refusing to back down, even when attacked by such powerful forces as the FBI.43

So the revolutionary rhetoric and artwork that originally appeared in the Panther was reproduced in other forms. During the 1970s, three books reprinted hundreds of the newspaper’s essays and editorial cartoons, and by 1990 several dozen additional books—including some published by such major houses as Random House and Simon & Schuster—had reproduced lengthy excerpts from the paper. The hunger for the ideology espoused in the Black Panther still did not abate. In the 1990s, a dozen more books were added to the holdings of American libraries and book stores, and several of the earlier books were reprinted. Finally, by the turn of the new century, the only surviving high-profile voice from the long-deceased newspaper was keeping the words of the publication alive by quoting from it on his own Website—www.bobbyseale.com.44

And so, despite the passage of time, despite White America’s overwhelmingly negative visceral reaction to the words “Black Panthers,” and despite the many covert and illegal acts the FBI committed in an effort to destroy the Black Panther, the radical concepts that were initially voiced in the paper in the late 1960s and early 1970s have experienced a vibrant life of their own. Not only have those ideas outlived most of the youthful revolutionaries who originated them, but those same concepts that were shunned by establishment journalism during the years that the Black Panther was being published have now been either embraced as accepted political doctrine or, at the very least, are now being seriously debated in the larger society and, therefore, are most definitely having impact on the mainstream of American thought.