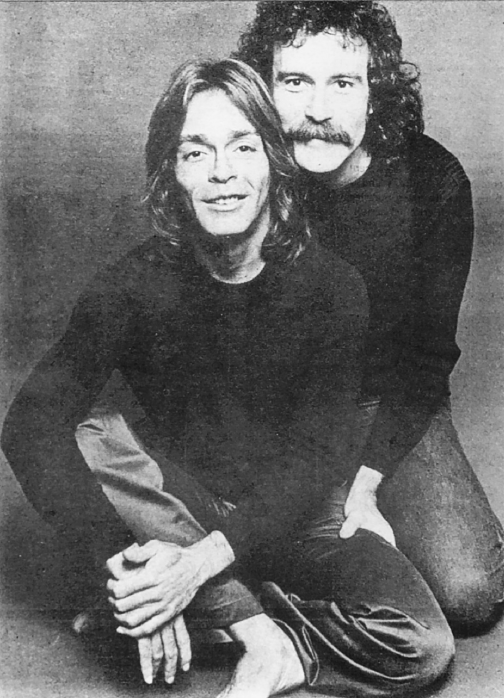

Like many leaders of the 1960s dissident press, Lige Clarke (left) and Jack Nichols grew their hair long as a symbol of their liberated attitude and lifestyle. (Photo by Eric Stephen Jacobs; courtesy of Jack Nichols)

The Counterculture Movement helped lay the groundwork for gay men and lesbians to demand equal rights. With the liberated attitude toward free love and sexual exploration celebrating male-to-male and female-to-female sexual activity as never before, the time clearly had arrived for homosexuals to come out of the closet and march boldly to center stage.

Gay people have never been content to follow meekly in the paths of others, however, so it took their own seismic event to ignite a true social revolution, and then their own dissident press to transform that historic moment into a full-fledged social movement. The event was the Stonewall Rebellion in New York City in June 1969, and the press was a network of lesbian and gay publications that fanned the spark of defiance into a raging forest fire that ultimately would engulf the entire country through the Gay and Lesbian Liberation Movement.

Stonewall spawned the in-your-face gay newspapers that voiced outrage, demanded justice, and shrieked at the top of their lungs. The upstart tabloids fed on each other, pushing the envelope of good taste further and further—and then further still. Screaming headlines, titillating images, revolutionary concepts, and primal-scream language often designed more to create heat than light—they all contributed to the fervor of journalistic dissidence.

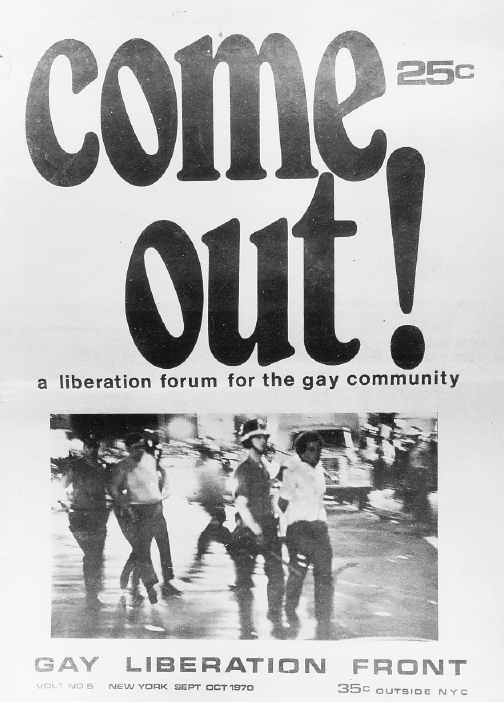

Merely listing the names of the papers that burst onto the streets of New York communicates a palpable sense of what they stood for: GAY, Gay Times, Come Out! The shockwaves reached other parts of the country as well, producing such colorful voices as Gay Sunshine and the San Francisco Gay Free Press on the West Coast and Killer Dyke in Chicago. The number of gay and lesbian publications being produced in 1970 surpassed 150, with a combined circulation of at least 250,000.1

The most important achievement of the publications was not amassing large numbers—although the figures were, indeed, impressive—but creating an arena in which lesbians and gay men could discuss what their social movement hoped to be. Editors and writers stood on the front lines of the ideological warfare, introducing the themes that would define this highly controversial social revolution for decades to come.

Martha Shelley, who participated in the Stonewall Rebellion and then became one of the most powerful voices of the era through her essays in Come Out! and Killer Dyke, later recalled: “It was that marvelous moment at the very beginning of a new adventure when everything—absolutely everything—seems possible. Every topic was on the table. We didn’t agree a lot, but we always gave each other respect. We’d all been involved in other movements where gay people were second class. No more. Now we had our own movement, and we were primed to debate just where that movement would take us.”2

THE STONEWALL REBELLION LIGHTS THE FUSE

The Stonewall Inn was the epitome of the grim realities of the gay bar scene in 1960s America. It was operated by three Mafia figures—Mario, Zucchi, and Fat Tony—who routinely referred to their clientele as “faggot scumbags.” Paying only $300 a month rent and raking in $5,000 every weekend, the trio turned a tidy profit, even after paying off the officers from the Sixth Precinct to keep the police raids to a minimum.3

The club lacked many amenities, including running water behind the bar. After a customer used a glass, the bartender merely dipped it into a vat of stale water and then refilled it again for the next customer. Despite the health hazards, people flocked to the nightspot because it had the only gay dance floor in the city and bartender Maggie Jiggs dealt acid and uppers with aplomb. Drag queens and chino-clad young men in their early twenties dominated the crowd; a few lesbians and a sprinkling of older men—known in gay parlance as “chicken hawks”—who lusted after the underage boys completed the nightly mélange.

June 27, 1969, was the day New York buried music legend Judy Garland, a favorite among gay men. Some 20,000 people had waited up to four hours in the blistering heat to view the icon’s body, with many of her admirers hitting the bars that night to unwind. Except for Garland’s funeral, that Friday night at the Stonewall seemed like most every other one. Then, at 1:20 a.m., eight policemen stormed through the front door—and all Hell broke loose.

After the officers herded everyone into the street, the patrons and bystanders began jeering at the police. If a single individual inspired the crowd’s resistance, it was a lesbian—she has never been publicly identified—who, when an officer shoved her into the street, pushed back. Emotions flared as the angry gays turned steely and began tossing beer cans, rocks, and even a couple parking meters that someone had ripped out of the sidewalk. When the officers retreated to inside the bar, the building suddenly burst into flames. The police somehow escaped the fire that night, but the social insurgents rioted every night for the next week, with their pent-up energy escalating into a full-scale rebellion involving 300 police officers struggling to control 2,000 newly empowered gay men and lesbians.

The mainstream press covered the riots much as it had covered previous events involving gay people—with scorn and ridicule. The headline “Hostile Crowd Dispersed Near Sheridan Square” above the New York Times story sent the message that gays were enemies of civilized society. The New York Daily News, for its part, portrayed the rioters as laughable: “Homo Nest Raided; Queen Bees Are Stinging Mad.” The disdainful tone permeating the coverage in the Village Voice was the most disheartening of all because the tabloid billed itself as an alternative to the establishment press, and yet its stories overflowed with mocking references—“prancing,” “fag follies,” “wrists were limp, hair was primped.”4

The only gay journalistic voice in New York at the time of the rebellion told a very different story. The “Homosexual Citizen” column in the sex tabloid Screw expressed unbridled enthusiasm by saying it was “thrilled by the violent uprising.” The column went on to place the pivotal event in historical context. “A new generation is angered by raids and harassment of gay bars, and the riots in Greenwich Village have set standards for the rest of the nation’s homosexuals to follow. The Sheridan Square Riot showed the world that homosexuals will no longer take a beating without a good fight. The police were scared shitless and the massive crowds of angry protesters chased them for blocks screaming, ‘Catch them! Fuck them!’ There was a shrill, righteous indignation in the air. Homosexuals had endured such raids and harassment long enough. It was time to take a stand.”5

GAY SETS A LIVELY PACE

Although that column ensconced its two authors as journalistic prophets of the post-Stonewall era, they were already firmly established as gay press veterans.

Jack Nichols and Lige (short for Elijah) Clarke met in Washington, D.C., in 1964. A year later, Nichols organized the first public demonstration to protest unfair treatment of homosexuals, leading a brave little band of ten activists who formed a picket line in front of the White House. Clarke, who had been drafted and was working at the Pentagon, did not march but lettered the signs that his lover and the other protesters carried in the historic event.

Like many leaders of the 1960s dissident press, Lige Clarke (left) and Jack Nichols grew their hair long as a symbol of their liberated attitude and lifestyle. (Photo by Eric Stephen Jacobs; courtesy of Jack Nichols)

Nichols and Clarke entered gay journalism in 1966, writing—both under pseudonyms—for a Washington-based monthly titled the Homosexual Citizen. A year later, they transformed themselves into children of the counterculture, abandoning the starchy nation’s capital and moving to the lower east side of Manhattan. Nichols stood six-foot-three and carried his million-dollar smile atop an athletic physique. Clarke was blond, lithe, and so strikingly handsome that he turned heads even at the trendiest of bars—gay or straight. In the new environs and intoxicated by the fumes of gay liberation, the attractive and gregarious couple began living large. Both men let their hair grow to their shoulders, wore bell bottom jeans and tie-dyed T-shirts, and experimented with the wide variety of drugs and sexual pleasures the bohemian neighborhood offered.

Nichols and Clarke then began writing their “Homosexual Citizen” column for Screw, which arguably was—and still is—the most vulgar newspaper in the history of publishing. Its debut edition in 1968 included a personal ads section called “Cocks & Cunts,” spicy reviews of X-rated films, and lots of nude photos. The raunchy tabloid soared to a circulation of 150,000.6

The “Homosexual Citizen” simultaneously achieved its own notoriety, as each column offered something that straight readers had never seen before: a positive portrayal of homosexuality. Whether Nichols and Clarke were talking about contributions that gay people had made to world history or the opening of the country’s first gay bookstore, the tone was invariably upbeat. In one column, they recalled their animated response when asked if they regretted not being straight. “The only answer we’ve got to this question is based on our present life together,” they wrote. “We’re having a ball!”7

Five months after the Stonewall Rebellion, Nichols and Clarke began editing their own newspaper, while also continuing to write their weekly column for Screw. GAY quickly became the newspaper of record for Gay America. The first anthology of gay nonfiction, The Gay Insider: USA, captured the essence of the spirited tabloid and its editors, writing: “Jack and Lige write a no-nonsense, unapologetic, vibrant, sexy, and liberated weekly message that is gobbled up by thousands like me, rendering the authors the most celebrated homosexuals in America. They are witty, wise, straightforward, and pretty.”8

Each issue of GAY featured a full-page photo of a handsome man on the cover—Lige Clarke appeared on the first one—and a plethora of homoerotic images inside. To illustrate a three-inch article about arrests at a pornographic bookstore, the editors chose a photo of Studio Bookshop employee Rick Nielsen. This was not, however, the standard one-column headshot. The five-inch-by-twelve-inch photo featured a full-body shot of Nielsen, from the front, wearing nothing but a seductive smile—his genitalia dangling freely.9

GAY was financed by Al Goldstein. Having established Screw as a successful enterprise a year earlier, the straight entrepreneur invested $25,000 in GAY in hopes of earning still more profits. Goldstein distributed the paper and found advertising to support it; Nichols and Clarke supplied the editorial content.

The new sense of gay liberation that exploded in Greenwich Village after the Stonewall Rebellion gave the weekly paper a ready audience. Within a month, some 25,000 people were plunking down forty cents for the paper, giving it the largest circulation in the twenty-year history of the lesbian and gay press.10

As a commercial enterprise, GAY eagerly accommodated to its advertisers. So as the number of Mafia-owned gay bars and bathhouses burgeoned in the largest urban center in the country, an increasing proportion of the pages were filled with graphic ads that gloried in full frontal nudity.

COME OUT! RAISES A RADICAL VOICE

The archetype of the revolutionary journals that erupted after Stonewall shrieked onto the streets of Greenwich Village in November 1969. In that inaugural issue, Come Out! demonstrated the combative stands it would take by demanding that gay and lesbian consumers boycott any business that was aimed at gays but owned by straights—such as GAY.11

Come Out! did not aspire to journalistic fairness but blatantly rejected the conventions of the established social and political order, including those of the Fourth Estate. The first issue called readers to action: “Power to the people! Gay power to gay people! Come out of the closet before the door is nailed shut! Come Out! has COME OUT to fight for the freedom of the homosexual; to provide a public forum for the discussion and clarification of methods and actions nexessary [sic] to end our oppression.”12

Come Out! was the printed voice of the Gay Liberation Front, born in New York City a month after Stonewall and quickly spreading across the country. The organization was composed of young gay men and lesbians whose revolutionary vigor had been inflamed by U.S. involvement in Vietnam, becoming to the Gay and Lesbian Liberation Movement what the Black Panthers had become to the Civil Rights Movement. The leftists demanded not only gay rights but the complete overthrow of American society.13

Come Out! was one of several radical newspapers that supported violence as a means of ending the oppression of gay men and lesbians.

The bi-monthly paper violated many journalistic standards. Pages often carried no numbers, and articles were riddled with typos and grammatical errors. Language was also more colorful and explicit than in most newspapers. Police were referred to as “pigs,” “fascists,” and “swine.” “America” became “Amerika.” The words “fuck” and “cunt” appeared with regularity.

Personal essays dominated the editorial content, along with a goodly number of letters from readers and reviews of books, records, and films. Illustrations consisted mostly of homoerotic drawings and photos. News articles were sprinkled throughout the twenty pages. Typical items praised gay activists for disrupting an appearance by New York City mayoral candidates and denounced the Village Voice for censoring a classified ad Come Out! had placed to solicit articles—the Voice had deleted “Gay Power to Gay People” from the copy for the paid ad, saying the word “gay” was obscene.14

In keeping with their nonconformist leanings, Come Out! staff members eschewed hierarchical structure. The paper was published collectively by members of the front, with no one holding the title of editor. During a gay press panel discussion, a staff member explained the philosophy behind the lack of structure: “We have a definite view that the society is what’s fucking us up. That a capitalistic, heterosexual society is the root of all our problems. We think compitition [sic] and producing to earn money is the root of a lot of our problems.”15

The paper contained no advertising, and staff members received no salaries. Indeed, the very idea of paying journalists conflicted with the paper’s anti-capitalism credo. In a letter to potential contributors, the staff wrote: “Come Out! will not insult you by offering you payment.” Most of the paper’s 6,000 copies were sold on the streets of Manhattan; members of Gay Liberation Front chapters in Chicago, San Francisco, and Los Angeles sold the rest, at two bits a pop, in their home cities.16

EMBRACING VIOLENCE?

One issue that attracted considerable ink in the papers was whether activists were justified in using violence in their effort to achieve equality. GAY, the voice of moderation, opposed violence; Come Out! and other radical papers endorsed it.

Jack Nichols and Lige Clarke were convinced that the major force impeding the movement was ignorance. Straight people would grant gay people full equality, the editors believed, as soon as they became familiar with gay issues. So the editors supported acts of civil disobedience that raised the gay and lesbian profile. GAY endorsed “kiss-ins” and “dance-ins,” during which same-sex couples engaged in public displays of affection, by devoting front-page news stories and editorials to the events. The paper also gave extensive coverage to the first Gay Pride Parade up Sixth Avenue in 1970 to commemorate the anniversary of the Stonewall Rebellion. GAY drew the line, however, at confrontations that resulted in physical harm or property damage. Nichols and Clarke wrote point blank: “We abhor violence in any form.”17

Gay Sunshine was one of the several voices taking the opposite stand. “We as homosexuals must learn to be ‘Violent Fairies’ and shake off the silly passiveness idea that straights have handed us,” the Berkeley tabloid insisted. “We are Revolutionaries and not ‘Passive Pansies.’” Nor did Gay Sunshine pull any punches in identifying who should be the target of gay violence: “The enemy is straight society.” Pat Brown, a hippie with his blond hair hanging well below his shoulders, was one of the eight men in the collective that created the paper. He later recalled: “When you’ve been pushing for a very long time and you don’t see any progress, you do what you need to do to raise the visibility of your plight. We were willing to smash a few windows here and there. Cadillacs make wonderful barricades, and those big, huge gas tanks burn for a very, very long time.”18

The radical papers demonstrated their support of violence through the images that dotted their pages. Drawings of machine guns, rifles, hand grenades, bombs, and clenched fists were common, and occasionally a pig dressed as a police officer—inspired by the Black Panther—could be found wandering across a page as well. The central role that violence should play in the movement was also communicated by photos showing crowds of gay revolutionaries marauding through the streets, leaving overturned cars in their wake. The papers made the same defiant statement when they enlarged photos—sometimes filling an entire page—of the signs that demonstrators carried during mass rallies: “Seize Your Community,” “We Will Smash Your Hetero-Sexist Culture,” “Fuck This Shit!”19

Come Out! initiated violent rhetoric in its first issue: “We’re involved in a war—a people’s war against those who opress [sic] the people. Power to the People!” A year later when gays rioted after a police raid on a Village bar, Come Out! encouraged further violence by echoing the chants the demonstrators had shouted at the police—“You better start shakin’ ’cause today’s pig is tomorrow’s bacon!”—and crafting its own strident calls for violent action—such as “Destroy The Empire!” and “Babylon has forced us to commit ourselves to revolution!” The paper also urged readers to join the Gay Liberation Front’s rifle club to prepare for the armed combat that was on the horizon. Come Out!’s most pro-violence stand came when it proposed burning the buildings on the City College of New York campus because the school promoted “establishment thinking.”20

Gay Times, which consisted of one sheet of typing paper that editor John O’Brien glued to trees and utility poles, endorsed violence through the logo it carried at the top of the front page of every issue; the drawing showed a hand grasping a rifle, encircled with the words “To Love We Must Fight.” The paper clearly reflected the values of its editor. Today O’Brien speaks with pride of burning a record shop to the ground during the Stonewall riots because the store discriminated against gays. He also boasts that destroying the shop led to the owner’s heart attack and death. “I’m very proud of that,” O’Brien said. “He was a total bastard. Some people deserve to die.”21

Killer Dyke lived up to its militant name through both its artwork and its rhetoric. The members of the lesbian collective who founded the Chicago tabloid created one of their most memorable images by reproducing a likeness of Whistler’s mother sitting sedately in her rocking chair—with a machine gun in her hand. In its first issue, the paper warned: “Sexist pig oppressors … beware! Those motorcycles roaring in the night … is that the Killer Dykes foaming at the mouth? zooming to get you?!”22

The San Francisco Gay Free Press also insisted that gays would achieve equality only by wrenching it forcibly from straights. The tabloid peppered its pages with terms such as “gay genocide” and drawings of bullets exploding in the faces of police officers. Editor Charles Thorp promoted violence, he told his readers, because he had repeatedly been physically attacked while distributing gay papers. On one occasion, Thorp’s face had been slashed and on another he had been struck in the head with a baseball bat. A Free Press open letter to straight men stated: “I’ll not be your slave. I demand of you my complete freedom, and if that displeases you, I’ll take what is mine, by any and all means necessary. I’ve got my gun loaded. I’m rising up gay to smash your cock-power, understand?”23

The Free Press reported that gay revolutionaries were already preparing for violent action: “Guns are being loaded. Knives are being sharpened. Bombs are being made. We declare war on our oppressors.” The tabloid said that large numbers of gays were training hard for guerrilla warfare: “All are committed to violent Gay revolution.”24

FORMING A SEPARATE GAY NATION?

While many gay men and lesbians of all generations have enjoyed surrounding themselves with other gay people, post-Stonewall radicals went a giant step further. Buoyed by the sense of possibility that was wafting in the air, this militant minority insisted that contempt for homosexuality was so ingrained into the fabric of American life that gay people had no choice but to create their own society totally separate from straights. The issue of gay nationalism created another fault line that divided gay and lesbian publications into two distinct camps.

Among the most ardent champions of creating a gay state were the members of the Gay Sunshine collective. “We tried to isolate ourselves totally from straight society,” recalled Pat Brown. “All of us wanted to eat, drink, and sleep—especially sleep—gay. So separatism definitely was injected into our editorial content.” The Berkeley tabloid gave gay nationalism its blessing, saying: “It’s time for us to take full charge of our lives, to seize control of our own world and make it fit to live in. Homosexual separatism is essential.”25

A concrete proposal to create a gay nation emerged six months after the Stonewall Rebellion. In December 1969, members of the Gay Liberation Front in Los Angeles announced a plan to take over nearby Alpine County, centering on the town with the irresistible name of Paradise. They proposed turning the tiny resort community—population 367—into the first all-gay city in the world, complete with a gay civil service system and a museum of gay arts and history. Under California law, new residents of a county were required to wait only ninety days before becoming eligible to vote and removing current county officials from their jobs.26

The San Francisco Gay Free Press threw its support behind the proposal, surveying readers and finding that fully eighty-three percent of them supported the idea of a separate nation. “Gay people have given the Alpine Liberation Front a mandate to go on,” the paper wrote. The Free Press further suggested the county be renamed “Stonewall Nation” and encouraged wealthy gays to buy the nine major businesses in the county. The paper went on to propose that gay and lesbian welfare recipients move to the county so it could be declared “impoverished” and become eligible for millions of dollars in public assistance to finance gay public housing and free social services.27

Other dissident gay journalists, both radical and moderate, were less enthusiastic about Stonewall Nation. Martha Shelley of Come Out! and Killer Dyke recalled: “A lot of us said, ‘OK, let’s get real.’ I mean, blacks outnumbered us ten times over, and they made no headway at getting their own separate piece of land. It made no sense for us to waste our energy on gay nationalism.”28

Jack Nichols of GAY agreed. “I never really thought of it as a serious proposal,” Nichols said. “Sure, a lot of gays wanted to live in an all-gay world—that’s why the Village in New York City and the Castro in San Francisco became gay meccas. That was fine by us. But creating an entirely new all-gay society with no connections to the dominant straight society whatsoever? That just wasn’t going to happen. Why spend your time on some screwball idea like that when you could be working toward truly meaningful social change? Pick your battles, man, pick your battles.”29

By early 1971 when a Christian right organization threatened to respond to the gay initiative by moving its own members into Alpine County, it was clear that the proposal would not evolve into reality. After that point, the concept of Stonewall Nation became the makings of gay mythology. The gay and lesbian community ultimately came to think of the idea as nothing more than a joke.30

DRAG QUEENS AND DYKES ON BIKES: CELEBRATED OR SHUNNED?

One controversial issue that was debated in the late 1960s and has continued to polarize Lesbian and Gay America ever since is the role that fringe groups should play in the movement. Many people are uncomfortable with men who drape themselves in feather boas and “swish” their hips, or lesbians who dress in leather jackets and race Harley-Davidsons. Other people argue that this rich cultural diversity should be celebrated by inviting drag queens and dykes on bikes to lead the colorful parade toward sexual liberation.

GAY stepped boldly into the fray. In June 1970 it began a full-page feature with the cut-to-the-chase statement: “The drag queen is doing for homosexuality what the Boston Strangler did for door-to-door salesmen. Neither transvestites nor transsexuals serve any useful function for themselves or anyone else.” Despite a flurry of scolding phone calls and letters in response to the article, Nichols and Clarke held their ground. “The visibility of the drag queen has given society an erroneous impression of the nature of homosexuality: namely that we are men trying to be women and women trying to be men. We do not believe that drags, transvestites, and transsexuals have any inherent connection with homosexuality.”31

The radical papers, on the other hand, unequivocally supported welcoming drag queens into the movement. Gay Sunshine argued, in fact, that men who dressed as women epitomized not only gay liberation but also women’s liberation. “When a man in our society grows his hair long, puts on a dress, and walks among us, she is in effect giving up his male privilege. When every man is able to cross the sex role boundary, then and only then will women cease to be sex objects. Queens are in the vanguard of the sexual revolution.”32

Come Out! publicized meetings and social activities for transvestites and transsexuals. “We were always comfortable with drag queens,” Martha Shelley said. “I remember after Stonewall that the feeling of liberation was so euphoric that I knew I would never go back to a job where I had to wear skirts. So I gave all my old skirts to the drag queens. They loved them!”33

Killer Dyke supported transsexuals by insisting that straight society’s tolerance merely of ordinary-looking gay people was not enough. In one article, Shelley demanded that all of society embrace the full, glorious dimensions of Lesbian and Gay America. “We are the extrusions of your unconscious mind—your worst fears made flesh,” she wrote. “From the beautiful boys at Cherry Grove to the aging queens in the uptown bars, the taxi-driving dykes to the lesbian fashion models, the hookers (male and female) on 42nd Street, the leather lovers. We are the sort of people everyone was taught to despise—and now we are shaking off the chains of self-hatred and marching on your citadels of repression.”34

The San Francisco Gay Free Press did not merely talk the talk; it walked the walk. The paper made Angela Douglas, a male-to-female transgender, a strong and recurring editorial presence in its pages—first as a subject, then as a staff member. When Douglas was arrested for crossdressing, the tabloid blanketed the story across page one, complete with a two-inch-high headline: “Free Angela Douglas!” Coverage included a news article, photo, and appeal for funds to support her court battle. And when Douglas indicated that another of her desires—in addition to becoming a woman—was to become a journalist, the Free Press added her to the staff and published a first-person account of her travails. The paper concluded: “Right on, Baby!”35

SEXUAL MORES

One of the few elements of the evolving ideology that moderate and radical voices agreed on was that gay men and lesbians should discard the moral dictates established by straight society. In short, they believed that repressing sexual desires and limiting oneself to monogamous sexual relationships denied free will.

GAY editors Jack Nichols and Lige Clarke were resolute promoters of open sexual relationships. “Only first-class morons think they should have exclusive rights to their lover’s body,” the couple wrote. “Sensible people don’t go around asking, ‘Has anybody besides me been seeing, touching, or making use of your genitals?’” 36

Lesbian and gay journalists considered adopting new social mores to be fundamental to their liberation. Come Out! wrote: “No one has the rite [sic] to tell another what to do with his or her own body. We must be free.” Editorial content reinforced the point by adding a bawdy new dimension to reader-service journalism with articles such as a two-page spread titled “A Cocksucking Seminar” that discussed how to increase the pleasure of oral sex.37

The publications also expressed their support of liberated sexual mores through their explicit artwork. Come Out! illustrated its article on oral sex with several photos of men performing fellatio on other men, and it routinely published nude photos and drawings of both men and women. Killer Dyke printed several images of nude lesbian couples engaging in a variety of sex acts. Every issue of Gay Sunshine included photos and drawings of naked men, often with penises in full view, and a provocative article titled “Jesus Is Gay” was accompanied by a drawing of a nude Jesus Christ—complete with radiating eyes and fully developed penis.38

Editors Nichols and Clarke not only dotted the pages of GAY with photos of nude men and women but became intimately involved in homoerotic images when they appeared as the models in an artful two-page photo essay titled “A Man Loves a Man.” The photos showed the two handsome young men engaging in both oral and anal sex.39

Publications gave their editorial blessing to promiscuity and anonymous sex. “We gave each other a lot of space on sexual freedom,” Martha Shelley recalled. “Who the hell cared how many people you slept with?” That sentiment was translated into print in editorial content such as a Come Out! article celebrating the proliferation of gay “fuck bars” in the Village. The first-person piece stated: “The Fuck Room was exactly that! No games, no bullshit, no hassles—just simple, direct, down-to-the-nitty, old-fashioned sex! No little blue pill could come close to relieving the nervous tension that my two hours in that room did. I touched, I communicated, I related and I loved.”40

DEFINING A REFORM STRATEGY

Although the dissident papers were fully unified in the need to attack antigay injustice, they differed on exactly where to focus their efforts. What’s more, the status of the papers divided them into two distinct groups. Most existed because of the commitment and financial support of individual staff members or political organizations, allowing them broad latitude regarding the targets of their editorial assaults. But GAY, the paper with the largest circulation, would continue to publish only as long as Al Goldstein made a profit from it, and the fact that gay bars and bathhouses had emerged as major advertisers clearly compromised the paper’s choice of reform initiatives.

For GAY, an important battlefront was the unjust legal system. When a gay couple filed a joint income tax return, the paper showcased the act of defiance with an article, two photos, and an editorial. It also gave expansive coverage to two men who applied for a marriage license, fifty lesbians and gay men who staged a sit-in at a New York bar that refused to serve gay customers, and a male couple who joined the bridal registry at a Denver department store.41

GAY also fought to elect mainstream politicians who supported gay rights. The ideologically moderate newspaper reasoned that the winds of liberation had shifted the political tide in New York City to the point that it was time for candidates to court gay voters. The secret ballot, the paper argued, enhanced the political power of what was fast becoming one of the country’s largest voting blocs, saying, “Not every homosexual is ready to commit himself in public, but the voting booth is a very private place.” When Bella Abzug became the first mainstream candidate in New York history to woo lesbians and gay men, GAY gave her exuberant editorial support—and she won her seat in Congress.42

GAY did not, however, confront what many people considered Gay America’s most insidious enemy: the Mafia. The underground crime world controlled the bars that gays frequented, as it was the only force both willing and wealthy enough to pay off the police and keep the business establishments open and producing revenue. On the one hand, gays wanted to sever their ties with the Mafia; on the other, bars were the only public places that gays could come together to relax and enjoy each other’s company. But GAY faced the additional complication that Mafia-controlled bars and bathhouses represented its most lucrative source of advertising revenue. “It was hard to get advertising,” Nichols later said. “All we could get was the erotic stuff—bathhouses, bars, X-rated movie houses. It was very, very tough to get any other ads for a gay newspaper.”43

So, rather than railing against the Mafia, the country’s flagship gay paper wrote laudatory articles about the businesses the crime lords financed. Typical was the lead of a full-page piece that read more like an ad than a news story: “The Beacon Baths at 227 East 45th Street in Manhattan is well worth a visit.” The cheerleading tone was further enhanced by two photos of employees of the baths, including a nude shot of the manager.44

By contrast, New York’s noncommercial gay press vehemently attacked the Mafia’s stranglehold on the community. Come Out! led the way, launching the campaign on page one of its first issue: “Our friendly neighborhood tavern is a Mafioso-on-the-job training school for dum-dum hoods.” The same issue described the corrupt bar owners as “money-hungry opportunists.” The tabloid was relentless in its criticism, accusing the Mafia and police of marching arm-in-arm against gays: “All of New York’s gay bars are Mafia-run. When the Mafia bar-owners fail to pay off sufficiently, the pigs get unhappy and move in.”45

Gay Times joined the anti-Mafia campaign, with editor John O’Brien repeatedly criticizing the underground criminals for refusing to allow him to distribute his paper to their patrons. “The bars were hostile to the gay press. The concept of liberation was very threatening to them,” O’Brien said. “They wanted us to remain frightened and in the closet. As long as we were scared, they had a lock on us and our money. They knew that if gays became stronger, that lock would end. We would start operating our own bars, and they’d be out of business. They thwarted our every effort.”46

The radical papers did not rely solely on the impact of verbal assaults but also worked with their parent organization, the Gay Liberation Front, to create an alternative to the Mafia-owned bars. In the spring of 1970, the front sponsored dances at Alternate University, a progressive institution on Sixth Avenue. Come Out! promoted and covered the dances, stating: “The purposes which we set out for the dances are to provide an alternate to the exploititive [sic] gay bars in the city.”47

THE REVOLUTION SUBSIDES

Like many dissident presses, the radical gay publications that erupted in the late 1960s were short-lived. By the end of 1972, lesbian and gay radicalism had faded from the political landscape. The demise was due at least partly to a resounding lack of tangible progress in securing equal rights. Although the 1969 Stonewall Rebellion had energized the Gay and Lesbian Liberation Movement, that historic moment had failed to produce substantive changes in the status of the American homosexual. Only the states of Connecticut and Illinois legalized sex between consenting adults of the same gender. In early 1972, the New York City Council—at the very epicenter of the revolution—rejected a proposal that would have banned discrimination against gay people in employment, housing, and public accommodation. Later that year, Democratic presidential candidate George McGovern promised reform in federal employment and military policies for gay men and lesbians—and then was summarily trounced by Richard Nixon.

Also relevant was the disintegration of the Gay Liberation Front, home to the most radical and visible activists. The front fell victim primarily to internal unraveling because of a handful of members expressing grievances and sub-grievances and sub-sub-grievances, most of them involving the front’s structure. Many activists later suspected—although they could never prove—that the discontented voices were infiltrators the FBI had paid to join the front in order to destroy it.48

The full extent to which the FBI’s Secret War contributed to the decline of gay radicalism in the early 1970s is unclear, although there is no question that agents investigated gay press editors.

John O’Brien of Gay Times was a favorite. The agents believed that O’Brien had to be a straight communist who had infiltrated the Gay Liberation Movement—which they called the “Fag” Liberation Movement—because the twenty-year-old young man’s rugged appearance did not fit the FBI’s profile of a gay man. In their reports, agents routinely referred to gay men as “sissies” and “pansies.” So the agents thought O’Brien was a communist agitator who had joined the movement because such a virile young man would easily lead the weak-willed gay men into anti-American activities. After observing O’Brien distributing his paper, the agents conducted an intense investigation into the editor’s personal life, which became part of the 2,800 pages of material the FBI collected on post-Stonewall editors and other activists.49

Gay Times was not the only gay and lesbian publication that well-informed FBI agents were reading. They also collected copies of GAY and Come Out!, sending them directly to J. Edgar Hoover in Washington. Referring to the historians who disclosed after Hoover’s death that he was a closeted homosexual, John O’Brien quipped: “J. Edgar jacked off while reading our papers. I just know it.”50

Regardless of exactly how the director interacted with the papers on a sexual level, Freedom of Information Act requests have not revealed the same number of FBI terrorist acts against the gay and lesbian press as against the counterculture and Black Panther presses. One possible explanation is that the homophobic director and agents considered lesbians and gay men to be too ineffectual to be seriously concerned about.

From the historical distance of three decades, it is clear that Hoover and his lieutenants were wrong, however, as gay journalism played a central role in nourishing the Gay and Lesbian Liberation Movement during the three years that the revolutionary impulse held sway. For it was in the pages of the various papers that the movement’s bedrock ideological issues took root.

The publications succeeded in moving some issues to resolution. With regard to whether Gay and Lesbian America would redefine sexual mores for itself, the content of the publications—both editorial and graphic—showed that the answer was very much in the affirmative. Likewise, the issue of whether lesbians and gay men would create their own nation was resolved just as clearly—but in the negative.

Other questions were asked but not answered, with many of the issues still being debated today. The role that fringe groups, particularly drag queens, should play in the movement continues to divide the community. At the end of 1972, it also remained unclear which of the many reform efforts would be primary or if the battle would be fought simultaneously on many fronts—to gain legal rights, increase political clout, and break the Mafia stranglehold on the bars.

The question of whether violence should be a central tactic in the fight against homophobia was resolved by default; the issue evaporated as a major topic of discussion when the radical publications that supported it were extinguished in the early 1970s. Come Out! was buried in the same coffin as the New York Gay Liberation Front it spoke for. Others papers that were produced by individuals or collectives—Gay Times, Gay Sunshine, Killer Dyke, and the San Francisco Gay Free Press—did not have a sufficient financial base or workforce to sustain them.51

The single publication that survived the aftershocks of Stonewall was the only one with a combination of relatively calm voices and stable finances: GAY. The stances of the editorially moderate publication generally carried the day in the debates, and it was this commercial enterprise that possessed the fiscal stamina that would allow it to influence the next phase of gay and lesbian liberation, surviving into the mid-1970s.52

Joining GAY would be a reincarnation of one of the radical publications. Financial problems and splintering of energy among members of the Gay Sunshine collective ended the Berkeley-based tabloid in early 1971, but it reappeared a few months later as a commercial enterprise that communicated its message through substantive literary works and in-depth interviews with gay artists into the 1980s. Collective member Pat Brown recalled: “The gay press had been born and, like the movement, wasn’t going to die. Not ever. Those were heady days when we liked to allude to mythology. I’m sure we saw Gay Sunshine rising from its ashes like the phoenix. Well, actually, I’m not sure we said it that way then. But if we didn’t—what the Hell?—we should have.”53