As one of the most strident of the women’s liberation publications, Ain’t I a Woman? fully endorsed women taking up arms to fight sexism.

Although members of both sexes actively participated in the social movements that erupted during the tumultuous 1960s, none of those various efforts placed a high priority on securing equal rights for American women. In fact, the men who opposed the Vietnam War, created a counterculture, and fought racial oppression were every bit as sexist as other men. Gay males were somewhat more sensitive to women’s concerns—but not enough so to satisfy many feminists. “We have met the enemy and he’s our friend,” a female staff member wrote in one counterculture paper. “And that’s what I want to write about—the friends, brothers, lovers in the counterfeit male-dominated Left.”1

And write she did.

The author was Robin Morgan, and the paper she wrote for was Rat. In February 1970, Morgan was part of an all-woman cabal that seized the New York City bi-weekly and transformed it into one of the leading voices of the Women’s Liberation Movement.

“Rat must be taken over permanently by women—or Rat must be destroyed,” Morgan wrote in the article, titled “Goodbye to All That,” that became a manifesto for women revolutionaries. “We are rising, powerful, wild hair flying, wild eyes staring, wild voices keening, undaunted by blood—we who hemorrhage every twenty-eight days. We are rising with a fury older and potentially greater than any force in history, and this time we will be free or no one will survive.”2

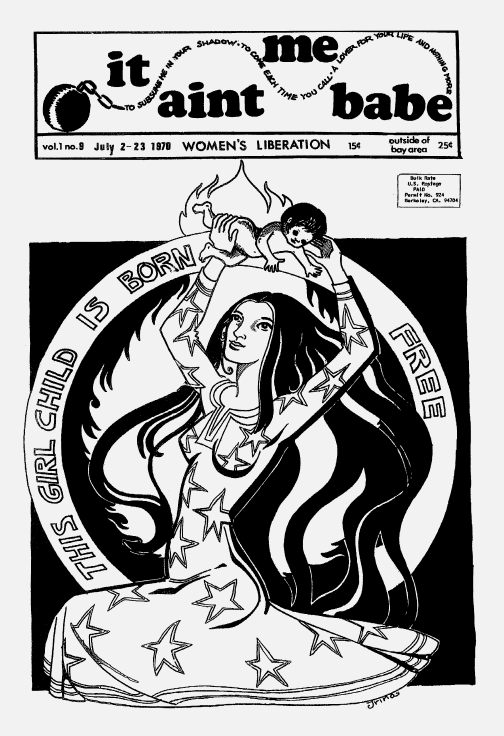

Morgan’s angry pronouncement struck a chord. During the early 1970s, women created some 230 feminist publications that demanded an end to gender-based oppression. Four months after the women of Rat commandeered that paper, like-minded women in Iowa City, Iowa, founded Ain’t I a Woman? as an equally militant voice in the Midwest. The network of papers quickly spanned the entire country—from It Ain’t Me Babe in Berkeley, California, to off our backs in Washington, D.C.3

Although the four publications differed in the stridency of their ideological positions, they shared several fundamental traits: All four were published by women’s collectives—some residential, others not—that eschewed the traditional hierarchy of mainstream publications by refusing to designate any staff member the “editor.” They all printed an abundance of material submitted by readers. All four papers refused to adhere to a regimented publication schedule—sometimes only a week passed between one issue and the next; other times that gap stretched to several months. They kept their cover prices low—usually twenty-five cents—and limited their advertising to feminist enterprises, such as other women’s liberation papers, so individual donations from members and friends of the collectives ended up covering most of the printing and mailing costs. In addition, none of the staff members received salaries, none of the papers made a profit, and none of the collectives was willing to divulge circulation figures for its publication—rejecting the concept as capitalistic and patriarchal.

The publications diverged significantly not only from the mainstream press and the male-dominated New Left presses that flourished during the era but also from the reform-oriented newspapers, magazines, and newsletters produced by local chapters of the National Organization for Women, founded in 1966 by Betty Friedan and other moderate feminists. For the women of Rat and their sisters at the various radical papers around the country would not be placated with a gradual increase in women’s rights; they demanded complete gender equity, and they demanded it immediately.

Historical context seemed to justify their militant call. Despite the Suffrage Movement gaining women the right to vote and the Birth Control Movement making contraceptive information widely available, a huge gap still separated American women from true equality. One way to gauge the lack of progress was to revisit the agenda that Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan Brownell Anthony had articulated in the pages of The Revolution beginning in 1868. A century had passed, but women in 1970 still faced the same problems that the pioneering publication had sought to erase: Job discrimination. Unequal pay. Sexual harassment. Inadequate political representation. Domestic violence. A legal system that continued to define abortion as an illegal act.

All of these issues had, however, at least moved into the mainstream of debate, thereby becoming too tepid for the new generation of female journalistic insurgents. So the leaders of the women’s liberation press defined a whole new agenda. The only issue that The Revolution had raised that was still prominent in the 1970s dissident women’s press was the one that, more than any other, would define feminist debate during both that decade and in the ones to follow: abortion.

FINDING A VOICE

Robin Morgan’s early adulthood took her through the same stages that many young women of her generation followed. First came her life as a devoted housewife. Morgan married a writer named Kenneth Pitchford in 1962, when she was twenty, and sought fulfillment by mastering the art of domesticity. “I felt legitimized by a successful crown roast,” she later wrote.4

Next came Morgan’s years in the New Left. While earning her living as an editor and proofreader for a publishing house, she committed her activist energies first to the Guardian, then to Rat. But she gradually came to realize that the male editors suppressed women by relegating them to typing and preparing food for the men—the true revolutionaries. Being limited to monotonous tasks, Morgan said, frustrated many of the women. “We were used to such an approach from the Establishment, but here, too? In a context which was supposed to be different, to be fighting for all human freedom?”5

An early indication of Morgan’s emerging radicalism came when she covered the protest against the 1968 Miss America Pageant. In the article she wrote for Rat, which was reprinted in numerous other counterculture papers, Morgan reported that 200 activists crowned a live sheep the real beauty queen and then “twenty brave sisters disrupted the live telecast of the pageant it-self, shouting ‘Freedom for Women!’ and hanging a huge banner reading ‘Women’s Liberation’ from the balcony rail.” Morgan’s coverage of the demonstration, which she had helped organize, was by no means objective. Her article called for “two thousand of us liberating women” to protest future pageants and ended by saying, “A sisterhood of free women is giving birth to a new life-style, and the throes of its labor are authentic stages in the Revolution.”6

So by February 1970 when the women of Rat seized the paper from its male editors, Robin Morgan—then the mother of a six-month-old baby boy—was at the vanguard. Although the women shared the various clerical, editorial, production, and distribution responsibilities in a rotating fashion, no one questioned that Morgan’s “Goodbye to All That” essay in the first issue of the new Rat was the most powerful piece in the paper, immediately establishing her as the movement’s leading oracle.

One of Morgan’s most controversial points was that the multifaceted social revolution that was underway could not, if it hoped to be effective, be led by white men. They were unacceptable leaders, Morgan insisted, because they were not victims of the society they were trying to overthrow but were, in fact, privileged and tyrannical. “A legitimate revolution must be led by those who have been most oppressed,” Morgan wrote, which meant “black, brown, and white women.”7

Morgan’s primary target was liberal men. First she summarized the low regard male leaders of the American Left had for women activists by quoting a racist joke: “Know what they call a black man with a Ph.D.? A nigger.” And then, without taking a breath, Morgan produced the sexist variation that had recently become popular among white men: “Know what they call a radical militant feminist? A crazy cunt.”8

Morgan then lambasted male activists in a litany of rhetorical condemnations. She chastised the men for listing women among the objects they wanted available to them after winning the revolution, quoting the leaders as demanding “free grass, free food, and free women.” Morgan also denounced the male leaders for telling aspiring young male revolutionaries to “fuck your women till they can’t stand up.” Morgan ended her searing attack with an eloquently simple statement she made on behalf of all feminists: “Not my brother, no. Not my revolution.”9

Overnight, “Goodbye to All That” became the guiding credo of the Women’s Liberation Movement. The widely reprinted essay was quoted, debated, cried over, and fought about—Morgan received death threats from numerous men. Words and phrases from the seminal statement were excerpted and printed on posters and banners, used for slogans, and read aloud during hundreds of the feminist consciousness-raising sessions that swept the country. When women in San Diego founded a radical feminist paper, they named it Goodbye To All That, and in the months and years that followed, women bidding farewell to male-dominated groups—such as lesbians who abandoned gay male revolutionaries to join their straight sisters in the battle for women’s liberation—referred to their pronouncements as “daughters” of Morgan’s clarion call.10

The powerful words published in Rat had simultaneously launched three mighty forces—the Women’s Liberation Movement, the network of newspapers that fueled that movement, and a torrent of radical feminist issues.

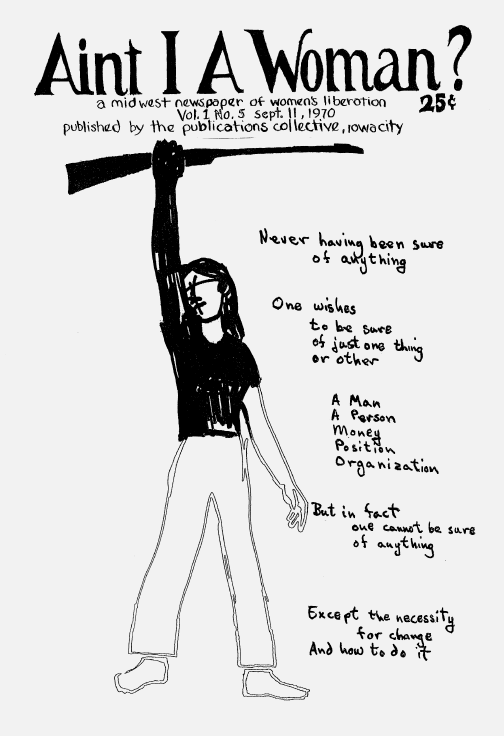

As one of the most strident of the women’s liberation publications, Ain’t I a Woman? fully endorsed women taking up arms to fight sexism.

CALLING FOR THE REVOLUTION

Robin Morgan, as the leading spokeswoman of the movement, made it clear from the outset that she and her followers would not be satisfied with a few halfhearted reforms. “Sexism,” she wrote, “is the root oppression, the one which, until and unless we uproot it, will continue to put forth the branches of racism, class hatred, ageism, competition, ecological disaster, and economic exploitation.” Previous efforts to improve American society had failed, she wrote, because they had been undertaken by men “for the sake of preserving their own male privileges.”11

In contrast, Morgan called for a feminist revolution that would affect every citizen—male as well as female. The movement would begin with “each individual woman gaining self-respect and, yes, power, over her own body and soul first, then within her family, on her block, in her town, state, and so on out from the center, overlapping with similar changes other women are experiencing, the circles rippling more widely and inclusively as they go.”12

As the printed voice of a social, political, and economic insurrection of vast scope and ambition, the women’s liberation press pulled no punches. The most militant of the feminist voices—like the Black Panther and the radical gay and lesbian publications of the era—exploded with images of rifles, pistols, bombs, hand grenades, and clenched fists, while shrill headlines reinforced the belief that American women were on the brink of armed rebellion: “Women Are Rising Up—They Are Angry,” “Seize the Land,” “Kick Ass,” “Death to All Honkies!”13

Like the violent-oriented images and headlines, the most extreme editorial statements were concentrated in the most militant of the papers. “Our struggle is against the male power system which is a system of war and death,” Rat defiantly stated in en early issue. “If in the process of that struggle we are forced to mutilate, murder and massacre those men, then so it must be.” Ain’t I a Woman? adopted an equally extreme position. “I want a revolution of women really castrating their men,” one essay read. “I want to eliminate men because they are murderers and destructive and fucked up.”14

The less militant voices called for change but stopped short of condoning murder or mutilation. It Ain’t Me Babe established a nonviolent stance by stating in its first issue that the members of the collective founded the paper “to defend our right to be treated as human beings”—not to do intentional harm to anyone. off our backs made the point in its inaugural editorial as well, saying, “Our position is not anti-men but pro-women.”15

EXPLORING FEMALE SEXUALITY

Throughout the first two centuries of American history, society had viewed sexuality almost exclusively in terms of bringing pleasure to men. So one of the major themes in the women’s liberation press of the early 1970s was acknowledging that sex could—and most definitely should—be enjoyable for women as well. Indeed, this theme provides a vivid illustration of how the various dissident papers approached issues.

off our backs, the least radical of the papers, encouraged women to enjoy sexual activity but not to be reckless. The Washington, D.C., paper counseled its readers to avoid unwanted pregnancies by practicing birth control. Still cautious about the long-term effects of the pill, oob advised its readers to use a diaphragm. “The contraceptive preparation is not harmful to the vaginal canal nor harmful if ingested orally,” one article reassured readers. The story then went on to describe step by step how to insert, lubricate, and remove the soft rubber device from the vagina.16

It Ain’t Me Babe was next on the ideological continuum, adopting an editorial stance only slightly more radical than off our backs. Typical of the sex-related items in the Berkeley paper was one submitted by a reader and titled “Sex: An Open Letter from a Sister.” The author described how she had felt like a failure for many years because she could not reach orgasm during intercourse with her husband, even though she easily did so by rubbing her hand against her clitoris. Only with the advent of the Women’s Liberation Movement, the woman wrote, did she begin talking with other women and discover that she was not a “freak” but that many women were unable to achieve vaginal orgasm. “I am no longer ashamed of my clitoral orgasm, but I am so embarrassed about my ignorance and how I let this go on for years and years, and tears and fears.”17

Ain’t I a Woman? adopted a much more radical stance than either off our backs or It Ain’t Me Babe, on female sexuality as well as other issues. One article, titled “Vaginal Politics,” argued that the first two steps women had to take if they were to embrace the pleasures of sex were to explore their bodies and to reject any sense of shame attached to bodily functions. Readers could accomplish both goals, the paper suggested, by observing their bodies closely through a complete menstrual cycle. The article then walked readers through the various stages, ending with the observation that, “just before menstruation, the vaginal walls will be swollen and tender, the cervix swollen and blue with veins seeming to pop out on it.” The most memorable element of the Ain’t I a Woman? story was not the words, however, but the photographs that accompanied them. The images showed a naked woman positioned so that neither her face nor her upper body was visible, the entire photo being filled with her exposed genitalia. To complete the picture, arrows had been drawn in to indicate the most intimate of the woman’s body parts—including the vagina and clitoris.18

Rat joined Ain’t I a Woman? at the radical end of the ideological spectrum. In keeping with that position, the New York paper’s content included a sexually explicit piece describing how a woman could bring herself to sexual climax. “It is time for all of us to learn how to make love to ourselves,” the article began. With an unprecedented degree of journalistic explicitness, the piece then described how a woman could masturbate by moving her hand in “a downward stroke beginning just above the root of the clitoris, passing over the clitoris and on down the mid-line, into the vaginal entrance, following the front wall of the passage and ending a little way inside.” Although the how-to description was the most memorable aspect of the article, which was accompanied by a drawing of a naked woman caressing her genitals, the story also carried a strong feminist message about female independence: “Masturbation is different from, not inferior to, sex for two. Also, with masturbation you don’t have to worry about someone else’s needs or opinions of you.” That message was reinforced by the article’s title—“Very Pleasurable Politics.”19

CELEBRATING LESBIANISM

One of the issues that drew an indelible fault line between the radical women’s liberation press and the moderate women’s rights publications was the concept of women loving women—not only emotionally but also physically.

National Organization for Women founder Betty Friedan and other reform-minded feminists of the early 1970s preferred to sideline lesbians, arguing that homosexuality was so controversial that supporting it would impede progress on what they considered more important issues, such as electing more women to political office. Friedan publicly accused “men-hating lesbians” of trying to dominate NOW, prompting some lesbians to dub her “the Joe McCarthy of the women’s movement.”20

Radical women, on the other hand, insisted that fully embracing lesbianism was absolutely fundamental to their movement. The various women’s liberation publications, whatever their level of stridency, were solidly positioned in this camp. Indeed, all of the publishing collectives included at least a few lesbians, with the number sometimes growing to a majority. In early 1972, the entire staff of Ain’t I a Woman? was composed of gay women, prompting the paper to announce that it was being published by “a collective of 16 women functioning as a world-wide conspiracy of Radical Lesbians—and don’t you forget it!”21

The single most frequent byline to appear above articles about lesbians was that of Rita Mae Brown, who wrote for Rat as well as off our backs. Brown often criticized the reform-minded feminists such as Friedan who said the only lesbians who encountered problems because of their sexuality were those who “wear a neon sign.” Brown began her response with a single word: “Bullshit.” She then continued, “One doesn’t get liberated by hiding. A black person doesn’t possess integrity by passing for white.”22

It Ain’t Me Babe, like other feminist voices, celebrated the importance of matriarchy as the lifeblood in the evolution of humankind.

Much of Brown’s writing was committed to analyzing exactly why so many people—especially men—hated lesbians. Part of the reason, Brown believed, was that “if we [women] all wound up loving each other, it would mean each man would lose his personal ‘nigger’—a real and great loss if you are a man.” She also argued that lesbianism threatened the male ego. “Men always explain lesbianism as a woman turning to another woman because either she can’t get a man or because she has been treated badly by men. They can’t seem to cope with the fact that it is a positive response to another human being. To love another woman is an acceptance of sex which is a severe violation of the male culture (sex as exploitation) and therefore carries severe penalties.”23

Brown felt the sting of homophobia on a personal level. After she began writing and speaking openly about her sexuality, she was verbally attacked. On a typical occasion, a man telephoned her at home and said, “I hear you don’t like men, you’re a dyke, a cunt lapper. I’ve put a bomb under your stairway.” Although the man then hung up and no bomb ever appeared, such comments still took their toll. Brown wrote, “I wish I could say that it didn’t hurt.”24

Another frequent byline in the various women’s liberation papers was that of Martha Shelley, who was simultaneously writing for the gay and lesbian press. In one piece that appeared in Ain’t I a Woman?, Shelley argued that feminists should not shun lesbians but revere them as models of women’s liberation. “The lesbian, through her ability to obtain love and sexual satisfaction from other women, is freed of dependence on men for love, sex and money. She doesn’t have to do menial chores for them (at least at home), nor cater to their egos, nor submit to hasty and inept sexual encounters.”25

The bylines “Rita Mae Brown” and “Martha Shelley” were joined by hundreds of others, as an army of readers who were not yet ready to publicly identify themselves as lesbians nevertheless had strong opinions that they were eager to express through the anonymity of their first names. It Ain’t Me Babe was particularly open to providing a venue for these women. “Mary” wrote, “As homosexuals, we must burst through our own alienation and jump the fences we set up in our own minds and in other people’s minds about who we are and whether or not we matter to the world,” and “Judy” echoed the same theme, saying, “The accusation of being a movement of lesbians will always be powerful if we cannot say, ‘Being a lesbian is good.’ Nothing short of that will suffice.”26

DEMANDING EQUALITY FOR WOMEN OF COLOR

Lesbians were not the only group that the leaders of the moderate wing of the women’s rights effort largely excluded from their movement. Betty Friedan and her nonrevolutionary cohorts focused their reform agenda on improving the quality of life for middle-class white women. Members of the collectives that produced the women’s liberation press, by contrast, insisted upon broadening the agenda to include women of color, most of whom were members of the working class.

The Iowa City women who founded their own newspaper in the summer of 1970 made their commitment to African Americans clear when they chose Ain’t I a Woman? as the name of their paper. Legendary former slave Sojourner Truth had first asked the poignant question in 1851 at a women’s rights convention. “The man over there says women need to be helped into carriages and lifted over ditches,” Truth said. “Nobody ever helps me into carriages or over puddles—and ain’t I a woman? Look at my arm! I have ploughed and planted and gathered into barns and no man could head me—and ain’t I a woman? I have born thirteen children and seen most of ’em sold into slavery and when I cried out with my mother’s grief, none but Jesus heard me—and ain’t I a woman?” Truth’s defiant words were an early instance of a black woman calling for definitions of female gender not only to extend to African American women but also to include women’s strength and suffering. Ain’t I a Woman? echoed those demands by quoting Truth’s words on the cover of its first issue, next to a drawing of the revered abolitionist with her clenched fist raised powerfully upward.27

off our backs, as a less radical women’s liberation paper, reached out to women of color by making sure a series of question-and-answer interviews with women in the local Washington, D.C., area included several African American women. The paper’s interview with a professional-level woman working in the U.S. Department of Health, Education and Welfare focused on why she had chosen not to join the National Organization for Women. “It’s difficult for me to empathize with some of the things they talk about,” the woman said. “If I were to define my priorities in order of importance to me in terms of my personal development, being female would not be first. What would be first is the fact that I am black.” The oob interview also included how the woman perceived NOW and other women’s organizations. “The groups that I’m familiar with,” she said point blank, “have been primarily white.”28

It Ain’t Me Babe’s editorial content related to women of color also criticized nonrevolutionary feminists. A piece titled “An Open Letter to Betty Friedan” read, “We relate to the black women in the south and the Chicano women in the southwest and the Indian women on the reservations who still can’t even read,” and then shifted to a question posed directly to Friedan, “Do you even know these women exist?” In a proactive step toward encouraging feminist consciousness-raising groups to include race in their discussions, It Ain’t Me Babe published a list of questions that it hoped would spur substantive conversations; first on the list was, “Are you more afraid of being raped by a white man or a black man? Why?”29

Rat was not content merely to interview women of color or to suggest questions for discussion but insisted upon racing full throttle into the tension between black women and black men. An article titled “From Black Sisters to Black Brothers” began, “Now here’s how it is. Poor black men won’t support their families, won’t stick by their women—all they think about is the street, dope and liquor, women, a piece of ass, and their cars.” The angry piece continued, “Black women have always been told by black men that we were black, ugly, evil bitches and whores—in other words, we were the real niggers in this society—oppressed by whites, male and female, and the black man, too.”30

FIGHTING BACK AGAINST PHYSICAL ABUSE

In addition to discussing the emotional and psychological pain that women were forced to endure, the publications also focused a great deal of their attention on the physical abuse of women—especially the rising number of rapes.

Robin Morgan raised this topic in an early issue of Rat. “Every day newspapers carry stories of atrocities committed against women: murder, rape, beatings, mutilations,” Morgan wrote. The rate of sex crimes had increased so dramatically, she continued, that the situation amounted to the “attempted genocide of a people on the basis of sex.” Neither Morgan, Rat, nor the other publications were satisfied merely to identify the problem of physical attacks on women, however, but also demanded an end to the abuse. “Women must defend our lives and bodies and minds against male violence, by any means necessary,” Morgan wrote. “We must learn and practice self- and sister-defense.”31

The other papers joined Rat in encouraging women to fight back against physical abuse, although their specific approaches to the topic varied.

off our backs, with a strong news orientation reflected in its subtitle “a women’s news journal,” concentrated on reporting instances of rape and other physical attacks. On occasion, though, the paper’s editorial stand came blaring through in its selection of what stories to report and how to present them. When a male police officer on the District of Columbia’s vice squad attributed the increase of rape cases to the Women’s Liberation Movement—“These liberated women,” he said, “have the attitude that they can walk the streets like a man”—oob headlined the item: “Sick Sick Sick.”32

Ain’t I a Woman?’s treatment of the physical abuse issue was consistent with its radical stripe. When the paper listed the specific needs of American women on its cover, an end to physical abuse was at the top. “We demand that women be given free self-defense and physical training,” the members of the Iowa collective wrote. “Their physical development has been stifled by their socialization into being ‘ladies.’ They must be trained, beginning at a young age, to be strong and capable of defending themselves. The rape and beating of women will end only when it becomes just as dangerous to attack a woman as a man.” Ain’t I a Woman? made the same point, perhaps even more dramatically, through its images. One early cover showed a young woman standing tall with her arm raised over her head holding a rifle—a feminist warrior poised for battle.33

But the women’s liberation publication that, more than any other, embraced the theme of women defending themselves against physical attack was It Ain’t Me Babe. The Berkeley paper began its campaign on the cover of its premier issue, filling the page with a story headlined “Self Defense for Women” and a photo of a young woman in a karate stance. “We have depended on males to protect us too long,” the article began. “It is time that all females learn to defend themselves. Women’s physical weakness and its psychological consequences can only be overcome through developing their bodies. We demand that self defense instruction be provided by the university [of California at Berkeley], by towns, schools, businesses, welfare departments—all institutions which have control over women’s lives.”34

That demand was the opening round of a relentless campaign by It Ain’t Me Babe to persuade women to fight back. Numerous articles offered practical tips on how women could protect themselves. Opting to defy not only the conventions of female roles but also the grammatical conventions of capitalization, one piece began: “your attitude is essential. refuse to be a passive victim. attackers assume we will attempt no self defense. many men are so cocksure that a simple kick in the shin can set you free.” The article went on to advise women to arm themselves with mace (“carry this in your pocket, you may not have time to open your purse”) and to kick an assailant with the side of her foot rather than the front (the side is stronger and covers more surface than the toes). The article ended by saying: “if he attempts to choke you, don’t give up; both his hands are occupied and you can stab his eyes with your fingers. if he just won’t quit, hit at the hollow of his throat with your finger tips. this can knock him out. if you’re extremely strong and angry, it can kill him.”35

The most extreme aspect of It Ain’t Me Babe’s crusade against physical attacks was the paper’s plan for how convicted rapists should be punished. “if men had an arm chopped off every time they raped one of us, they could not get more than 2 women.” Recognizing that many readers would think that cutting off the arm of a rapist was too severe of a punishment, the paper went on to offer a defense of the radical proposal: “they are not fighting fair. if you are polite and harmless, he may get your daughter in 10 years.”36

CRUSADING FOR ABORTION RIGHTS

The most ubiquitous issue in the women’s liberation press during its early years was one that would remain a topic of rancorous debate throughout America for decades to come. In 1970, abortion laws varied widely, with about half the states allowing the procedure only when the woman’s life was in danger and the other half allowing it in some circumstances, such as in cases of rape.

Although the women’s liberation papers were united in their desire that abortion be legalized in all instances nationwide, they differed in the tactics they employed to show their support. On this most contentious of issues, the most strident publications spoke with a voice that was loud, shrill, and filled with a sense of outrage. One article in Rat read, “We pledge a campaign of terror against any man who tries to deny us the right to control our own bodies. No more passive demonstrations!” And a piece in Ain’t I a Woman? screamed, “Sisters, remember—health care is a right and not a privilege! DEMAND THAT RIGHT!”37

off our backs chose a very different approach. Although the paper published many essays and editorials in support of abortion rights, most of its coverage on the topic was in the form of news stories. Hundreds upon hundreds of articles covered every aspect of the abortion-rights campaign—from speeches, debates, and conferences to mass marches, public demonstrations, and guerrilla theater productions. The paper also documented both advances and setbacks in legal cases at every level of the court system and in state legislative initiatives from coast to coast. oob called the campaign to legalize abortion the most important women’s rights effort since the suffrage campaign, and, because of that stature, the effort deserved saturation coverage—and saturation coverage it got.38

Although all the stories provided the who, what, when, and where of the news event at hand, many of them clearly communicated a pro-abortion-rights point of view as well. A reporter covering a planning meeting for a national abortion-rights conference in New York City concluded her story with the comment, “I, personally, was impressed by the consistently well thought out, articulate positions presented.” Likewise, an article reporting Maryland Governor Marvin Mandel’s veto of an abortion-rights bill ended with the statement, “Remember, Marvin will be up for re-election in November.”39

In addition to summarizing the most recent developments in the abortion-rights campaign, off our backs also promoted upcoming events. An article about 3,000 women participating in a rally in Washington ended, “The Women’s National Abortion Action Coalition, which organized the demonstration, is holding its next national coordinating committee meeting December 18th at 12 at the GWU [George Washington University] Student Center.” oob also printed sample statements it encouraged readers to personalize and then deliver before local judges and government officials, such as, “I ______ wish to present the following personal testimony concerning abortion.”40

off our backs readers often learned more about developments in the abortion-rights campaign than readers of mainstream newspapers did. When Dr. Ernest Lowe, chief of obstetrics at D.C. General Hospital in Washington, told women’s liberation leaders that he would not allow his doctors to give abortions because the procedure was “boring and distasteful,” oob readers heard the quote, but Washington Post and Washington Evening Star readers did not. Similarly, when Massachusetts legislator Joe Ward said he wouldn’t support legalized abortions just because of “some broad who gets herself knocked up in some hotel,” oob readers again heard the quote, but readers of the Boston Globe did not.41

It was not only oob’s vigilance in covering the various developments in the abortion-rights campaign that kept readers informed but also the paper’s willingness to undertake investigative reporting. After abortion became legal in New York state and pregnant women from throughout the East Coast began traveling there for the procedure, an off our backs reporter interviewed a number of women to make sure that the various New York clinics were providing patients with proper medical care. They weren’t. One clinic, the reporter wrote, gave women “a physical exam which includes complete blood and urine lab tests, a Pap test, blood pressure, temperature, listening to the heart, and a complete medical history.” But a second clinic, the reporter continued, “merely asks a woman about her medical history via a questionnaire.” The reporter gave the first clinic a grade of “A,” the second one a “C.”42

During the three years between oob’s founding in February 1970 and the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision to legalize abortion in January 1973, the paper’s coverage of the abortion-rights campaign was without peer—not only among women’s liberation papers but among all news outlets. For no other journalistic organization in the country exhibited oob’s combination of a consistent focus on women’s issues, its news-oriented approach to women’s liberation, and its location in the nation’s capital.

EXPANDING THE SECRET WAR TO THE WOMEN’S LIBERATION PRESS

It must have been excruciating for the virtually all-male FBI of the early 1970s—a legendary bastion of male chauvinism—to admit that a group of females had become such a powerful force that it was necessary for the bureau to expand its Secret War to the women’s liberation press. Nevertheless, the agents rose to the occasion and made the dissident papers a target of their harassment campaign.

The FBI first set its sights on the most radical of the publications. The women who commandeered Rat from its male editors made arrangements with a New Jersey company to print the paper. After FBI agents visited the printer and threatened to prosecute him on obscenity charges related to Rat’s explicit articles about female sexuality, however, he refused to continue doing business with the paper. The women eventually located another printer, but the additional effort sapped time and energy that they otherwise could have devoted to their primary purpose of writing material aimed at liberating the American woman. FBI agents also monitored Rat’s mail, opening and reading correspondence before postal officials delivered it. The agents confiscated many of the letters and then harassed the women who had written them—thereby causing many readers to stop buying the paper.43

The FBI next focused its attention on the other vociferously radical voice of women’s liberation, Ain’t I a Woman? The agents hired a female informant to infiltrate the collective by arriving in Iowa City, claiming to be destitute, and appealing to the women to help out a sister who had been victimized by the country’s patriarchal system. “We offered her a spare room in the house where our collective lived,” an Ain’t I a Woman? staff member later wrote. After the woman began asking an inordinately large number of questions, members of the collective became suspicious and distanced themselves from her, prompting the woman to leave after about two months. In the wake of her departure, however, a number of Ain’t I a Woman? staff members had altercations with local police regarding their drug use and homosexuality. The officers were so familiar with the activities inside the collective that the information clearly had come from the infiltrator.44

As women’s liberation gained momentum, FBI agents realized that the most effective movement publication was neither of the ideologically strident papers but the women’s news journal being published in the very shadow of the bureau’s headquarters in the nation’s capital. So in the spring of 1971, agents from the Alexandria, Virginia, office initiated a comprehensive campaign of intimidation against off our backs. The opening shot came in the form of a memo to J. Edgar Hoover that criticized the most recent issue of oob because it featured a drawing of labor activist Mary Harris “Mother” Jones on the cover, which the agents interpreted—in quite a stretch of the imagination—as signaling that the paper’s staff was planning to use racketeering tactics to force middle-of-the-road women to join the abortion-rights campaign. In reality, the cover was merely commemorating Jones’s birthday by suggesting that her famous quotation highlighted on the cover—“Pray for the dead. Fight like Hell for the living”—was an apt motto for the contemporary effort to fight on behalf of women who otherwise might die while having the unsanitary abortions that women had to resort to because the procedure was illegal in many states.45

That memo launched an FBI effort to intimidate oob’s printer, the Journal Newspapers, Inc., so it would stop doing business with the women’s liberation paper; that effort failed. Later memos documented the FBI’s attempt to coerce members of the off our backs staff to provide information about the paper’s internal operations; that attempt also failed. Despite the FBI’s lack of success, the agents still created considerable anxiety within the collective. “We were very concerned about the possibility of government disruption of off our backs,” two members later wrote. “Several times, women worried that other women who had contact with the newspaper might be government agents.”46

A LEGACY BOTH NARROW AND BROAD

off our backs not only survived the FBI’s covert efforts to destroy it but went on to achieve an unparalleled longevity among women’s liberation publications—and, indeed, among the legion of dissident publications that erupted in the 1960s and early 1970s. Still being published today, the Washington, D.C., paper circulates to 29,000 committed readers worldwide. Rat, Ain’t I a Woman?, and It Ain’t Me Babe all ceased publication by 1975.47

From the distance of more than three decades after the women’s liberation press came into being, this genre of the dissident press appears to have been effective on two distinct levels.

First, the papers provided a venue for the ideas, concerns, and life experiences of an enormous number of women who otherwise may never have raised their often-disquieting voices. In fact, the papers launched the writing careers of numerous women who went on to enjoy highly successful publishing careers.

One example is Robin Morgan. After her “Goodbye to All That” essay in Rat became a cogent manifesto for women’s liberation, Morgan went on to publish more than a dozen books and a plethora of poems and essays. The most high-profile among Morgan’s many works is Sisterhood Is Powerful, an anthology of essays that served as the catalyst for thousands of women to change both their personal aspirations and their daily realities. First published in 1970, Sisterhood Is Powerful is one of the most important feminist tracts ever written and is still being read today by new generations of feminists.48

Rita Mae Brown is another widely respected author whose work was first published in the women’s liberation press. Brown made a major contribution to the country’s perceptions of lesbians in 1973 when she wrote the best-selling Rubyfruit Jungle, a semi-autobiographical novel that shattered lesbian stereotypes by depicting gay women as smart, fun-loving, and beautiful. Brown has gone on to write a dozen additional books.49

The second legacy of the women’s liberation press is in the advancements among American women that took place simultaneously with the publishing of the papers. Most significant of those victories was the 1973 Supreme Court decision that legalized abortion nationwide. That monumental event marked a watershed in the struggle for gender equality, as it established—more than any other event before or since—a woman’s right to control her own body. Despite many assaults on that right, it has remained in place.

Progress has been made regarding other controversial themes raised in Rat, Ain’t I a Woman?, It Ain’t Me Babe, and off our backs as well. Sex is no longer seen as a pleasurable activity for men only, lesbian rights are now a staple element on the feminist agenda (including that of the National Organization for Women), equality for women of color has not been achieved but certainly has been established as a goal of most fair-minded Americans, and the abundance of self-defense classes and rape-prevention educational programs speaks to the priority that American women place on protecting themselves.

By the late 1970s, Robin Morgan had already published an inventory of other indications that the American woman had succeeded in entering a new phase in her liberation. Morgan wrote of the proliferation of women’s health centers and shelters for battered women in cities and towns across the country. She also applauded the emergence of women’s studies as an academic discipline on college campuses and the growing number of women’s bookstores—and the thousands of feminist-oriented volumes to fill their shelves. Morgan documented an explosion of women-owned businesses, too, writing, “Restaurants, craft shops, self-defense schools, employment agencies, publishing houses, and small presses—the list goes on an on.”50

Reinforcing her stature as one of the Women’s Liberation Movement’s most insightful theorists, Morgan also noted the changes that were taking place in feminism itself. She acknowledged that many critics were saying that the women’s movement was dead. “Such death-knell articulations are not only (deliberately?) unaware of multiform alternate institutions that are mushrooming,” Morgan wrote, “but unconscious of the more profound and threatening-to-the-status-quo political attitudes which underlie that surface.” Feminists were not retreating, Morgan wrote, but were maturing beyond what she called the “ejaculatory tactics” of the radical early years of the movement—so vividly expressed in the most strident of the women’s liberation papers—“into a long-term, committed attitude toward winning.” The new generation of women’s rights leaders, Morgan continued, “know that serious, lasting change does not come about overnight, or simply, or without enormous pain and diligent examination and tireless, undramatic, every-day-a-bit-more-one-step-at-a-time work.”51

Refusing to take a defensive or apologetic stance regarding the less-revolutionary phase that American feminists had entered, Morgan wrote: “We’ve only just begun, and there’s no stopping us. The American woman is maturing and stretching and daring and, yes, succeeding, in ways undreamt until now. She will survive the naysayers, male and female, and she will coalesce in all her wondrously various forms and diverse life-styles, ages, races, classes, and internationalities into one harmonious blessing on this agonized world. She is so very beautiful, and I love her. The face in the mirror is me. And the face in the mirror is you.”52