THREE

Felice Rahel Schragenheim was born at the Jewish Hospital in Berlin on March 9, 1922, a year in which many people lost their entire life savings. It was said that the Jews got rich on the inflation, which wasn’t true, but it offered those who had come down in the world a convenient excuse for anti-Semitism. Several months after Felice was born, Germany’s Jewish Foreign Minister, Walther Rathenau, was murdered by right-wing radicals in the pay of nationalist “patriots” who were opposed to the Weimar Republic. Rathenau, who had proudly acknowledged that he was a Jew, was one of the most cultured men of his time, and more than likely served as a model to Felice’s parents, who shared a dental practice on Flensburger Strasse in Berlin’s Tiergarten district.

Felice’s father, Dr. Albert Schragenheim, was born in Berlin in 1887, and served as a field dentist in Bulgaria during World War I. He married Erna Karewski, also a dentist, when he was on leave from the front in January 1917.

“Where did this blond child come from?” friends of the family asked in astonishment. Felice’s light-colored hair had gradually darkened to a mousy brown by the time she entered the Kleist School in April of 1928. Soon thereafter the family moved to Berlin-Schmargendorf, to Auguste Victoria Strasse, a quiet street lined with linden trees. Felice spent a secure and comfortable childhood there in a splendid home with lush gardens; the family also owned an automobile and a motorboat. She was called ’Lice, Fice, or Putz by her parents and her sister, Irene, and was the family favorite. Her parents were a handsome couple; her mother with her carefully marcelled bob, her father slender and narrow-shouldered, with prematurely gray hair at his temples. He wore round, nickel-frame glasses and the ubiquitous bow tie—the picture of casual elegance.

The Schragenheims’ friends were liberal and socialist-oriented Jews who believed in assimilation and turned up their noses at the Yiddish-speaking “Galicians” who lived on Grenadierstrasse. Lawyers, doctors, and artists frequented the house, among them the writer Lion Feuchtwanger and his sister Henny, related to the family on Felice’s father’s side, and whom Felice called “Uncle” and “Aunt.” A rabbi as well was counted among the family friends, for the Schragenheims, though not devout, observed tradition; each Sabbath, the candlesticks had their place on the elegantly set table. And on the evening before Passover, the children ran through the house looking for traces of leavened bread, a custom they pursued avidly due to the sweets their parents hid for them in remote corners of the house. The only thing missing from this perfect childhood was a Christmas tree. Their mother had nothing against it; for her, Jewish celebrations were an empty ritual, but their father stood firm.

Berlin Jews were well acquainted with the Schragenheims’ dental practice. I knew a dentist once . . . many of them would recall when the name Schragenheim was mentioned, even a decade later, after they had emigrated to England. In Berlin in 1933 half of all physicians and dentists on the public health insurance rolls were Jews.

In 1930, when Felice was eight years old, her parents had a serious automobile accident while on vacation. Their Fiat convertible, with trailer in tow, overturned on a forest road, landing upside down. Putz and Irene lost their beautiful mother, who was thirty-eight. Felice would later recall that when their dazed father returned to Berlin his hair had turned snow white. But a mere two years later he married a stylish young woman with dark, almond-shaped eyes and a perfectly oval face. Käte Hammerschlag not only became Dr. Schragenheim’s wife, she also worked as his office assistant. The daughters were less than enthusiastic about their nineteen-year-old stepmother, who came from a wealthy household, and they never quite forgave their father for betraying their mother. But Dr. Schragenheim soon had other things to worry about.

In 1930 he served as head of the Welfare and Insurance Office of the Reich Association of German Dentists, and at the same time was a member of the dental section of the Association of Socialist Physicians, a fact that caused some disquiet during the elections of the Prussian Chamber of Dentists in 1931. But Albert Schragenheim’s days as a functionary were numbered. Following Hitler’s “seizure of power,” all Jewish executive members and their representatives, nineteen in all, were forced to resign their commissions. The “Decree on the Practice of Dentists and Dental Technicians Under the Health Insurance Plan” of June 2, 1933, removed Communists and Jews alike from the national health insurance plan. Former front soldiers like Dr. Albert Schragenheim were spared for the time being, according to the “Law on the Reinstatement of Permanent Civil Servants.”

Between April 1, 1933, and the end of June 1934, six hundred Jewish dentists of the Reich were “shut out,” the anti-Semitic propaganda of members of the medical profession surpassing even that of the Nazis. Previously, everybody who was anybody in Berlin went to a Jewish doctor. The growing number of professional bans on Jewish hospital staff doctors opened up positions for those of their Aryan colleagues who hadn’t made the grade the first time around. On May 12 the Gross-Berliner Ärzteblatt [Journal of Greater Berlin Physicians] demanded the “banning of all Jews from the medical treatment of German Volksgenossen, because the Jew is the incarnation of lies and deceit.”

In 1934 the “Aryanization of Private Insurance” was introduced. “Personally unreliable,” “non-Aryan,” and “politically unfit” physicians no longer had their bills reimbursed by private insurance companies. Lists of “non-reimbursable” physicians and dentists were made public. The Reich Agency for Jews established a relief organization for those dentists excluded from the insurance plans, which offered retraining as dental technicians and advice on emigration. England was the emigration country of choice, because foreign dentists were allowed to practice their professions there without being subjected to additional examinations. But requests for work permits far outnumbered demand.

Around this time, or perhaps even sooner, Dr. Schragenheim bought a house on Carmel Mountain in Palestine, but sold it again because the climate didn’t agree with him. He did make provisions for his daughters, however: The Haavara Agreement of 1934 enabled him to buy Palestinian securities, which he deposited for Felice and Irene at two Tel Aviv banks. This agreement allowed cooperation between the Palestine Trust Company for the Export of German Industrial Goods—set up by the Reich Ministry of the Interior—and the Zionist Jewish Agency for Palestine.

On March 18, 1935—Felice and Irene were thirteen and fifteen years old, respectively—Albert Schragenheim died at the age of forty-eight. “I was at the grocer’s around the corner,” recalled Felice’s former classmate Christa-Maria Friedrich. “A woman burst in and called out, “Dr. Schragenheim is dead! The doorbell rang and it startled him so that he fell over and died.”

His death spared his being subjected to the Nuremberg Racial Laws issued the following September. He was buried at Weissensee Jewish cemetery. In 1937, on the occasion of the Führer’s birthday, he was posthumously awarded the “War Veterans Cross of Honor” by the president of the Berlin police, “in the name of the Führer and Reich Chancellor.”

The young widow, Käte Schragenheim, moved with her stepdaughters into an apartment on Sybelstrasse in the Charlottenburg district of Berlin. Käte, called “Mulle” by the girls, took her duties as stepmother seriously, to the great regret of Irene and ’Lice. Now they could only smoke at night in bed, when Käte’s watchful eyes were turned elsewhere. The two girls considered the elegant woman rather silly and kept their contact with her to an absolute minimum.

Until 1932 Felice attended the Kleist School on Levetzowstrasse, right next to the synagogue that later was to serve as a “collection camp.” When she was eleven she transferred to the Bismarck Lyceum, a secondary school for girls in a nineteenth-century building located in Grunewald, the elegant villa district not far from Königsallee, where Walther Rathenau had been murdered in 1922.

The first measures to be instated in education after Hitler seized power were the reintroduction of corporal punishment, which had been banned during the Weimar Republic, and the “German greeting” at the beginning of each class. Though the Bismarck Lyceum on Lassenstrasse was conservative, it was not Nazi. It was Queen Luise’s portrait that hung in every classroom, not Hitler’s, and the teachers only unwillingly obeyed the order to greet each class with “Heil Hitler” as they entered the classroom. The Lord’s Prayer continued to be recited at school ceremonies, as it had been prior to 1933, and only then were the German national anthem and Horst Wessel song intoned.

In April 1933 the “Law Against the Overcrowding of German Schools and Universities” was issued. The percentage of non-Aryan pupils and students was not permitted to rise above that of the general population, and was set at no more than 1.5 percent of new enrollments and no more than 5 percent of the “rest.” The law did not apply to students whose fathers had fought in World War I.

Christa-Maria Friedrich:

It’s odd that I can so clearly remember the moment when I saw Felice for the first time. It was after the Easter holidays in 1933. We had just moved up to the Quarta, the seventh grade. The lawns next to the entrance to the school were not fenced in yet, and you could sit comfortably on the little wall if the school building hadn’t opened yet. They didn’t open the doors till around quarter to eight. Surprisingly, I once got there so early that I had to sit and wait on the wall. Pretty close to me a very young woman was standing, holding the hands of two girls. The woman looked too classy to be a nanny, but too young for a mother. When we were later all seated in our new class, I saw the younger of the two girls, Felice. It didn’t take long for us to discover that we walked the same way to school. She lived diagonally across from me. On our many walks to and from school together I learned from her what the Social Democrats wanted and who the Zionists were. And when I had to play organ at the prayer meeting on Mondays, she held the handle of the broken motor for me. Felice was smart, well-read, very alert, athletic, sometimes boldly brazen and wonderfully happy—really a perfect buddy. With her broad shoulders and long legs she always seemed a bit masculine. She wasn’t pretty in a conventional sense, but she had an inner charisma that radiated from her big, light brown and gray-green eyes. Although we weren’t really close friends, we often saw each other in the afternoons, usually at my place.

On September 4, 1933, Felice received her certificate for endurance swimming, having swum for seventy-five minutes in the Lunapark pool in Berlin’s Halensee district. It would not be long before she was forbidden to swim in public pools. In the summer of 1935 a sign appeared at the outdoor pool in Wannsee carrying the message: “Swimming and admission prohibited to Jews!” But at the urging of the Foreign Office it was removed in preparation for the Olympic Games to take place the following year. Felice joined Bar Kochba, the Jewish Sports Club.

Personal contact between Jewish and non-Jewish girls was made almost impossible with the passage of the Reich Citizens Law of November 1935. Pressure intensified following the breather that was created before and during the Summer Olympics. “At the present time Felice does not give the impression that she is in top form physically; that is one reason her responses are sometimes inadequate. Nonetheless, once again she has earned positive marks overall,” wrote teacher Walther Gerhardt on Felice’s class certificate dated October 8, 1936. Felice appears small and delicate in a class photo of June 1936. She was exempt from attending history classes, in which “World Judaism” was discussed, and perhaps had her skull measured in Ethnology class.

AND YET—

There are those who carry on today; they are

Poor and unsuccessful they say,

Who flirt continually with disaster,

Yet almost choose it as their master.

But this world, for my measure,

gives me much that grants me pleasure.

On sunny days I go into town

and see great personages of renown;

Records and books I look upon

with joy, and poems and scarves of chiffon.

I love the theater, Klabund I read,

and laughter is healthy and something I need.

Other people truly do

find my attitude taboo;

Whether or not it is their choice—

there is much in this world for which I rejoice.

[APRIL 6, 19—?]

But this school was a good choice for Felice nevertheless. Walther Gerhardt, who taught history and Latin, and whom the girls fondly called “Bubi,” might have worn the gold party insignia on his lapel, but he was a good-hearted man who had probably long since turned away from National Socialism internally. And yet he dutifully registered in his class book the “race” of each of his students: “a.” for “Aryan,” “h.a.” for “half-Aryan,” and “n.a.” for “non-Aryan.”

Despite the large number of students who left the school in 1937, 58 Jewish girls still remained among a population of 343 at the Bismarck Lyceum, far more than the maximum quota allowed. This was perhaps due to the fact that the heads of many of the old Jewish families were war veterans. One student, who completed her studies in 1933, recalled that among her graduating class of 23 girls, only 7 were Aryan. The school’s director, Dr. Friedrich Abée, was highly regarded by parents who wished to spare their child a Nazi education. When Berlin’s schools were closed in the summer of 1943 there were still “half” and “quarter” Jews attending Felice’s school. Ilse Kalden, who graduated in 1943, wrote in the school’s chronicle:

Each school year new students joined our class from other sections of Berlin, even from other central German cities. To us, they seemed shy and unsure at first, until they gained in confidence. Slowly we discovered that almost without exception they all had suffered because of their religious beliefs, and that they had been expelled from other schools because somewhere in their family tree was a Jewish forebear. They all fled to Dr. Abée and were accepted without reservation. He even housed some of them in his own home.

Officially, however, the school was “Jew-free” in 1939. The removal of the daughters of merchants, university professors, surgeons, bankers, industrialists, and theater directors “due to parents’ relocation” had occurred in stages. On March 27, 1936, Felice’s sister, Irene, received her school-leaving certificate “to attend school abroad.” Five other girls in her class left at the same time, for the same reason. One year later at least eight other students withdrew, among them Felice’s best friend, Hilli Frenkel. In the school newspaper of 1937 is printed a farewell poem written by Felice to Marie-Anne Hartog, a banker’s daughter:

IN MARIE-ANNE’S ALBUM

“Just say a soft good-bye”—

The day after tomorrow,

Your schooldays’ great sorrow

Belongs to days gone by.

What we attained, that for which we strived,

Is “once upon a time” now, but I feel

That though I have been left behind,

You shall yet achieve your “feminine ideal.”

[MARCH 1937]

“What I Wish to Make of Myself—My Feminine Ideal” was the theme of an essay assigned to Felice’s class in the 1936–37 school year. Compared with “Blood Is a Very Special Fluid,” “Air Defense Is Necessary” and “The Heroic in Ancient Germanic Religion”—topics which students at other Berlin schools had been assigned since 1933—Felice’s high school was conspicuous in its restraint. A test question in math is interesting as well:

A ship crossing the Mediterranean to Jaffa, at 32˚5' long., 34˚45' lat., has given its position as 34˚45' long., 27˚17' lat. What course must it take?

This question is difficult to interpret: Is it a veiled reference to the Jewish students’ future prospects, cynicism, or a premature giving in to “Jews out and on to Palestine,” the official “Jewish policy” of that period?

The “half-Aryan” Olga Selbach joined Felice’s class at Easter 1937. Felice chose the plump Olga, who was always chewing her fingernails, to be her close confidante. When the school day ended in summer they would hurry to the swimming pool at the Reich sports field, and in the winter they visited each other at home, stretching out lazily on the couch, giggling, to talk about sex. As Olga, though almost two years older, was completely inexperienced, Felice could boast at will, always returning to the subject of lesbian love. When Olga appears deeply impressed, Felice lays it on even thicker. She had undergone an operation as a child, she said, something to do with her ovaries, and ever since then she had had these lesbian feelings. Olga was positively determined to be worthy of the friendship of a niece of Lion Feuchtwanger. Felice’s dream was to become a writer like her “uncle,” and the two girls polished their style by composing love letters. “Let’s cultivate our feelings,” Felice would say, and then they would think up imaginary people to whom they wrote passionate letters. Olga’s were addressed to a Russian man she called “Vasja.”

At Easter 1938 the Bismarck Lyceum was renamed the Johanna von Puttkamer High School, after Bismarck’s wife. On July 22 Jews were issued identification cards marked with the letter J. That fall only one “full-Jew” remained in the class. Felice, in fact, was the last.

On October 11, 1938, Felice received her last regular school report: “Felice has been able to retain her favorable position in the class,” her teacher, Walther Gerhardt, noted in his appraisal. The sole grade of “very good” that Felice earned was in English.

UNFORTUNATELY

True, we spoke of ancient sagas,

Of colonies far removed from here—

But how to ask the way in English

We haven’t mastered yet, I fear.

I have no right to criticize,

I do not wish to make a fuss,

But “over there,” I realize,

Is something else. What will become of us?

Just how are we to make it through?

Not even you yourself can say!

Dear Fräulein Dr. Merten, you

instructed us, now we must pay!

[AUGUST 9, 1938]

But Felice’s chances of going “over there” appeared slim. As the situation grew even more critical for Jews with the annexation of Austria in March 1938, and it became increasingly clear that the League of Nations was unable to control the growing refugee problem, President Roosevelt called a conference for the establishment of a new international refugee relief organization. In July 1938 representatives from thirty-two nations traveled to the French spa of Evian-les-Bains. The conference opened with an offer from the United States to extend its quota for refugees from Germany and Austria to the maximum—increasing it to 27,370 people. Following this, one delegate after another apologized for his country’s low immigration quota. The delegate from England would not allow debate on the issue of the British mandated territory of Palestine, and made it known that Great Britain, overpopulated and burdened by a large unemployment figure, was in no position to accept Jewish refugees.

On Kristallnacht, the pogrom night in November 1938, as synagogues burned throughout the German Reich and tens of thousands of Jews were dragged off to concentration camps, the world momentarily reacted with shock and sympathy. Holland, Belgium, France and Switzerland allowed thousands of Jews to cross their borders without passports or money; nor did they turn away illegal refugees after these borders were closed. “I cannot believe,” President Roosevelt stated indignantly, “that such things can occur in a civilized land in the twentieth century.” But when asked if he would support a loosening of immigration laws he cited national quotas that had been set by law in 1924.

After Kristallnacht even the most patriotic Jews realized that they would do well to abandon their homeland, at least for the present. Those who still were in a position to leave attempted to do so. But the Haavara Agreement, which had allowed some thirty thousand Jews to emigrate to Palestine, was annulled on November 9. And whereas in previous years Jews could pay a twenty-five percent “Reich refugee tax” and take the rest of their capital assets out of the country with them, any export of capital was banned as of June 1938.

In 1938, 140,000 people left the Third Reich. Those who stayed behind were, for the most part, the elderly, and single women. Half of the Jewish population remaining in Germany was over fifty years of age. While it was true that women exhibited a greater willingness than men to emigrate, more men actually left the country than women. A woman’s presence was required where the need was greatest; women served as community workers, nurses and teachers in the social welfare institutions of the Jewish community, which more and more people were coming to depend on. In the communal kitchens women cooked for those who could not cook for themselves. And women remained behind because they felt responsible for their elderly parents. In 1933 women made up 52.3 percent of the Jewish population; by 1939 that figure had risen to 57.5 percent.

Felice’s schooldays came to a sudden end as well, for on November 15, 1938, Jewish boys and girls were forbidden to attend public schools. “Following the heinous assassination in Paris, no German teacher can be expected to give instruction to Jewish schoolchildren,” read the decree issued by the Reich Minister of Education. “It is also clear that it is intolerable for German pupils to sit in the same classroom with Jews. Over the past several years the segregation of the races within the educational system has been realized for the most part, it is true, but the remaining Jewish students attending German schools with German boys and girls can no longer be tolerated.”

Felice, one of those remaining, received her school-leaving certificate “at the order of the Reich Minister of Education.” It was signed by her teacher, Walter Gerhardt, and headmaster Dr. Friedrich Abée. Walter Gerhardt issued one last evaluation: “Felice was a quiet, friendly, gifted, and hardworking pupil.”

The rest of Felice’s report book remained empty. She was sixteen and a half years old. When she left she took with her the school library’s German-English dictionary. “Stolen on November 2, 1938,” is written defiantly in green ink on the inside cover of the book.

OBITUARY

Certificate in hand, my school career

now finds its slow and certain end.

Last act, the iron curtain here

Closes on what I might have been.

One year more and I would have earned

my diploma, having played my part.

Instead this list of what I’ve learned,

States I was quiet, hardworking, smart.

Yes, gone those lovely days in time,

When once I dozed to Schiller’s “Clock,”

Though much preferred was Scheffler’s rhyme

Awakening me and signaling “stop.”

Playing hooky, passing notes, my relinquished

School pass—all passé.

Only I remain, dismissed and hindered,

A ninth-grade student without a grade.

[SEPTEMBER 11, 1939]

On November 16, 1938, Felice’s fellow students were curtly informed that she no longer would be attending the school. No one asked questions—they all knew what it meant. Even Olga went through a moment of shock that lasted for weeks. No one visited Felice. When Olga accidentally ran into her on the street one day Felice looked unhappy and lost. Olga invited her home, and Luise Selbach, seeing the suffering in Felice’s eyes, opened her motherly heart to the teenager. Luise, who was Jewish, lived in a “privileged mixed marriage,” ran a strict household, and soon accepted Felice into it as a fourth daughter. She was capricious, witty, and prone to theatrics. Her authority in the home rested not so much on her loud voice as it did on her capacity to inflict psychological suffering. And she was totally unpredictable. In the midst of laughter she suddenly would be reminded of some past transgression that no one else could even recall. But Mutti’s apartment in Berlin-Friedenau was also a warm and hospitable refuge. Fice and Olga would hold serious discussions on the future of the world, in the company of their pretty classmate Liesl Ptok. They read Marx, Spinoza, Brecht and Tucholsky. Other times, sitting backwards on their chairs, they played “Going to Jerusalem,” with Mutti accompanying them on the piano. Fice had found a family again.

Today, the Johanna von Puttkamer High School for Girls is called the Hildegard Wegscheider High School. Hildegard Wegscheider was a representative of the Social Democratic Party who served in Prussian parliament until 1933. On September 3, 1998, two plaques were unveiled, one in German and one in Hebrew, to commemorate the fifty-eight Jewish girls who attended the school in 1937.

MINOR INQUIRY

In deepest winter do you all

Still translate Latin, full of dread,

There in the niche by the art room wall,

Mathematics running through your head?

Are you still sneaking on the sly,

Up to the balcony’s soothing sun?

And for this paean to the sky,

Must you pay with extra homework done?

Is Bubi still racing around on outings

Faster than a fast express?

Is Basche still threatening and shouting,

And wearing her sofa-cover dress?

Is Inge Matthie still always late?

Have you once again been apprised of the rules?

Is Fräulein Merten still so discreet

As to tear up the notes she finds at school?

Are you still writing—the past for me

Is still the present, of course, for you.

It is only memory that allows us to see

What is now past in a golden hue.

[FEBRUARY 1939]

The Schragenheims now too began to make concerted efforts to emigrate. On October 22, 1938, Irene was declared of legal age by a ruling of the Municipal Court of Berlin-Charlottenburg, and she and Felice, still a minor, signed a “partition of inheritance agreement.” Effective October 31, 1938, the following was recorded as property of their father’s estate, to be divided equally between Irene and Felice:

1. Securities

a. In the value of 94,448.75 Reichsmarks (RM), deposited at the Prussian State Bank of Berlin;

b. one land deed Hanotaiah Ltd. Plantation and Settlement Company, Tel Aviv (5% land grant bond of 1934) at a face value of 814,522 Palestinian pounds. At a median rate of exchange for Palestinian pounds this comes to a total of RM 3,389.64;

c. 162 Kerem-Kajemeth-Leisrael debentures at a face value of 6 Palestinian pounds each, on deposit in the name of the Schragenheim sisters at Haavara Limited in Tel Aviv, valued at 972 Palestinian pounds, or RM 7,916.90;

2. Jewelry at a total value of RM 745;

3. Claims in the total value of RM 2,339.09.

The estate is valued at RM 108,823.08, therefore each sister is to receive RM 54,411.54.

It was agreed that the majority of the debentures on deposit at Haavara Limited were to go to Felice, in order to enable her to emigrate to Palestine. Should she succeed in leaving Germany, Irene’s share would then be credited to her.

At this time, Irene had already returned to Berlin after a two-year stay with relatives in Stockholm. She attended a trade school in Berlin, presumably until the Kristallnacht. She had left the Bismarck Lyceum in 1936 “to attend a school abroad,” as was noted on her school-leaving certificate. She emigrated to London in 1939, and was hired on a trial basis in February 1940 as a nurse in the St. Pancras Hospital. The earliest of her letters from England that survived, and which reached Felice through the Red Cross, is dated April 4, 1942.

On January 6, 1939, Felice’s legal guardian, attorney Edgar von Fragstein und Niemsdorff, informed Käte Schragenheim that he anticipated that the Foreign Exchange Office and the Reichsbank would agree to the partition of inheritance between Irene and Felice, and listed the securities available to Felice should she and Käte emigrate.

On January 16 the Continental Illinois National Bank and Trust Company of Chicago confirmed to the American consul that physician Walter Karewski, Felice’s uncle, the brother of her deceased mother, and his wife maintained a savings account in the amount of $2,091.04. Dr. Karewski, who called himself Walter Karsten in his new homeland, had lived in the United States since June 1936. On January 20 he signed an affidavit before a notary public applying for an immigration visa to the United States for Felice, a “housemaid” by profession, due to “conditions in Germany.” An additional affidavit was signed by Jennie L. Brann, who had lived in the United States all of her life, and who listed herself on the yellow form as Felice’s second cousin. On January 18 the Trustee and Transfer Office of Haavara Limited in Tel Aviv confirmed to the British Passport Office that the above-mentioned debentures on deposit at the Anglo-Palestine Bank Ltd, valued at RM 12,000, were being held in trust for the two daughters of the late Dr. Albert Schragenheim.

On December 6, 1938, Jews were no longer allowed to take certain streets in Berlin’s inner city. Sections of Wilhelmstrasse and Unter den Linden were put under a “Jew ban.”

Gerd Ehrlich:

Everything is transitory, and even the disturbances of November ’38 came to an end. “Normal” life went on. A constant stream of people flooded the consulates, that’s true, but it was not easy to emigrate. In addition to an entry permit to another country, difficult enough to obtain, one also needed an exit permit issued by the Gestapo. A passport office was set up on Kurfürstendamm, and one heard very little that was positive in connection with it. I personally always got hung up at the consulates. . . . The life we led was in no way desperate, however. We still had our relatively large apartments and for the most part could move about the streets in safety. But you had to take care not to jaywalk or commit some similar “crime,” because then the game was up. The police had strict instructions to punish harshly any Jew who committed such a misdemeanor, which generally carried a fine of one Reichsmark. I knew of cases where Jews landed first in jail and then in a concentration camp because they disregarded some traffic rule. I myself once had my name taken down by a police officer because I was riding my bike on a prohibited street. For some inexplicable reason he didn’t bring a charge against me; that was the end of the matter, at any rate.

As of January 1, 1939, Jews were ordered to add the name “Sara” or “Israel” to their family names on all pieces of identification. Felice became Felice Rahel Sara Schragenheim. Jews were forbidden to attend public theaters, movie houses, concert halls or cabarets. The theater run by the Jewish Kulturbund, and the Jewish movie houses were the only places where Jews could escape the bleakness of their everyday lives. The “New Reich Chancellery,” designed by Albert Speer, was opened on January 9, and on January 24 the “Reich Central Office for Jewish Emigration.”

Berliners were complaining that the supply of coffee was running low. “Germans, drink tea!” the coffee merchants urged. As regulations governing Jews soon were published only in the Jewish newspaper, the Jüdisches Nachrichtenblatt, it was made easier for Aryans to close their eyes to what was happening outside their front doors.

“Should Jews in international finance once again succeed, inside and outside Europe, in plunging the nations of the world into a world war,” Hitler threatened in an address aimed at Washington on January 30, 1939, “then the result will be not a Bolshevization of the earth, and therewith the victory of Judaism, but the destruction of the Jewish race in Europe.”

On February 4, 1939, Felice’s grandmother, Hulda Karewski, presented to the American Consulate an affidavit signed by her son Walter, together with an additional affidavit signed by Sam Maling, an American citizen and merchant, whose wife, Hazel, was a friend of Hulda. Sam Maling attested before a notary that he resided in a five-room apartment at the Chicago Beach Hotel, earned $1,500 a month, and had private assets valued at over fifty thousand dollars. He declared that he was a law-abiding citizen and had never been arrested for a crime or for any other misconduct. Nor did he belong to any group or organization whose goal was the overthrow of constitutional order. To the best of his knowledge and belief, the same held true for the applicant. Hulda Karewski, seventy years old, informed the American Consulate that in a registered letter of December 22, 1938, she had requested to be assigned a number on the waiting list, and asked that the matter be expedited, as her son was in possession of “first papers,” and her presence was urgently required in his household.

As of February 21, 1939, Jews had to surrender all objects in their possession made of gold, silver, platinum, pearls, or gems, with the exception of wedding rings. At the end of April a “Rental Law for Jews” was passed. It was left to “residents of a building alone” to decide “as of which date the presence of Jewish tenants is felt to be burdensome.” Jews who were forced to vacate their apartments were sent to “Jewish houses.” The Schragenheims were forced to move out of the apartment on Sybelstrasse and went to live with Käte’s parents, the Hammerschlags, whose ten-room apartment at Kurfürstendamm 102 was accommodating an ever-increasing number of Jews. “She moved to her step-grandparents on Kurfürstendamm,” recalled Christa-Maria Friedrich. “She had a room there and lived among the white furniture with a rubbed-varnish finish, which were not hers and didn’t match her taste at all.”

THE MOVE

Ultimo, the flat stood strange

And empty, now mere storage room.

Paper and rags around us arranged

What long had been “home” into a tomb.

Shards bring luck—the Chinese vase

Now believes that too, praise

God. Burly moving men do race

Around with piano and bookcase.

Spots on the wall where pictures hung,

Crates our only chairs,

Dead black wires from the ceiling wrung

Not a single flashlight anywhere.

Once our things are on the street

The packers set off for a quaff,

At precisely that moment, nice and neat,

God chooses to send a rainstorm off.

But then the moment finally arrives,

And the moving van sways away.

In future when we speak of our lives,

“That’s where we lived back then—” we’ll say.

[JUNE 12, 1939]

In the second half of March 1939 Felice took the Cambridge Proficiency Test in English at the Jüdische Waldschule Kaliski, a private Jewish school in the Dahlem district of Berlin, and waited for the day she would emigrate.

Refugees were permitted to take ten Reichsmarks in cash out of the country with them. Any violation of the foreign exchange regulation could result in being sent to a concentration camp or worse. Aryan Germans, who were permitted to travel abroad, increasingly departed elegantly attired in the furs and valuables of their Jewish friends, to get them out of the country. “Custodaryans” were storing Jewish possessions in their cellars and attics.

Until the late summer of 1941 the declared “Jewish policy” of the German Reich remained that of permitting the emigration of all Jews living in Germany. Of the 140,000 Jews who fled Germany in 1938, South America had taken in 20,000, and Palestine 12,000 legal, and an unknown but not insignificant number of illegal refugees. Perhaps 30,000 succeeded in being accepted by the United States. The rest were stuck in Western European lands of transit: France, Great Britain, the Netherlands, Belgium, and Switzerland. These countries began closing their borders when it became clear that the number of refugees being accepted abroad was shrinking. Foreign consulates were besieged by tens of thousands of people, but waiting lists were filled for years to come. By mid-May 1939 the British government had limited the number of refugees to Palestine to 10,000 a year until 1944, plus 25,000 refugees whose relatives would vouch for them.

Among those who made it to the United States was Felice’s best friend, Hilli Frenkel, who smuggled Felice’s mother’s jewels across the border in a package of sanitary napkins.

AUF WIEDERSEHEN!!

Earlier, when something funny occurred,

Whether humorous, wonderful, or absurd,

Touching little stories that ascertain

The continuing saga of Fraülein Merten,

Or Micha Nussbaum’s splendid bass,

Or some dumb school affair, whatever the case;

When I did something foolish in this place or that,

Or got in a big fight or some big spat,

An inner voice would always insist,

You really must tell Hilli this!

No more!

I sit here all alone now,

No thunderous applause to soothe my brow,

Nor do I hear that silly laugh,

A friendship quarrel’s aftermath.

Yet thrice a day, and often sorely,

When I pretend to be Evelyne Corley,

Or of lovely Chekhova catch a glance,

Or am struck by a hit song’s sweet romance—

I have to tell her, occurs to me then,

I have to tell Hilli, tell my friend!—

But in a few years time, just you wait,

This no longer will be our fate.

Then we’ll see each other again,

And everything that happened up ’til then,

All the little scandals, and what I’ve read,

What I’ve written, and what’s in my head,

Whom I’ve contacted and whom I’ve provoked,

And the very best of all my jokes

Manna for our silly souls . . .

Hilli, I’ll tell you in repose!

[MARCH 1939]

On March 15, 1939, the “Relief Organization for Jews in Germany” affirmed that in February 1937 Felice had appeared before the review board of the Bismarck Lyceum and successfully passed her home economics examination. She was therefore “totally suited to accept a position in a British household.” Felice’s little lined notebook from her cooking class has survived the decades, filled with recipes for chocolate soup with macaroons, breaded and unbreaded roast cutlet, hollandaise sauce, crumb cake, short pastry, semolina pudding, Kathreiner barley malt coffee, broth with egg, a ragout of game, apple bread soup . . .

THOUGHTS ON THE FUTURE

I like to dream of my career,

of cars and sun, of beauty and gold,

I think of blue seas far from here,

of journalism and worlds untold.

To far lands one can go, atlas in hand.

I do it gladly, well aware

That my life will change in some other land,

And my small star still is shining somewhere.

Yes, if only I were far away—

Once there I could continue my dreaming,

And then I would finally have my career,

If only in cooking and cleaning.

It’s good that we were given hope,

And self-deception, so we cannot see

Our guest appearance in this life

For what it is—tragicomedy.

[MAY 1938]

On March 16, 1939, Dr. Israel Ernst Jacoby attested in English that Felice was “neither mentally nor physically defective,” nor suffered from any contagious diseases. On April 1 she appeared at police headquarters on Alexanderplatz to have her fingerprints taken. The executive board of the Jewish Community on Oranienburger Strasse informed Felice Sara Schragenheim on April 18 that her emigration tax was set at 2,080 Reichsmarks, and requested that she deposit securities to cover this amount in the special depository of the Jewish Community at the Commerz und Privatbank AG.

A COMPLICATED INNER LIFE

The word “forbidden,” today contains

Everything which to us remains,

Except yellow benches and future fears.

No swimming, dancing, or movie dreams,

Neither jewelry nor equal rights, it seems,

May we keep. At best our tears.

So it will be nice to go away,

I wanted to travel anyway.

And yet it is weeping that I roam,

Because this pace we understand,

Because as strangers we leave this land,

Because what is missing is the bridge leading home.

[JUNE 23, 1939]

Aimée and Jaguar—Lilly Wust (right) and Felice Schragenheim, taken with a self-timer at the Havel River, August 21, 1944.

Felice, in a photo taken by Lilly, at the Havel River, August 21, 1944.

Lilly, in a photo taken by Felice, during the summer of 1944 on the balcony of Lilly’s apartment at Friedrichshaller Strasse 23.

Lilly’s parents, Margarethe and Günther Kappler, Lilly’s half brother, Bob, and Lilly, circa 1919.

(from left) Lilly’s father, Lilly’s husband (Günther Wust), Lilly’s mother, Lilly with son Bernd, summer 1937.

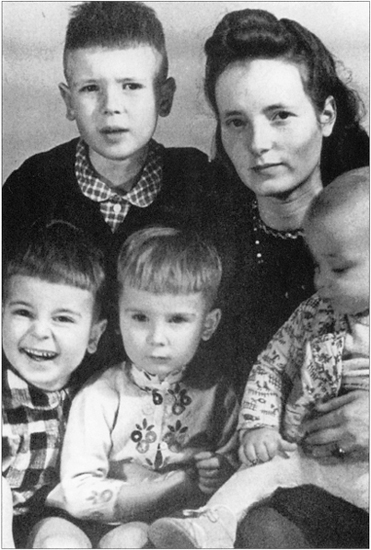

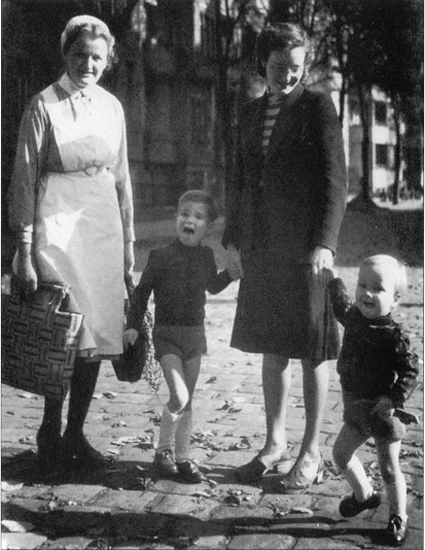

Lilly with her sons, Bernd, Eberhard, Reinhard, and Albrecht in February 1943, taken by Felice’s friend Ilse Ploog.

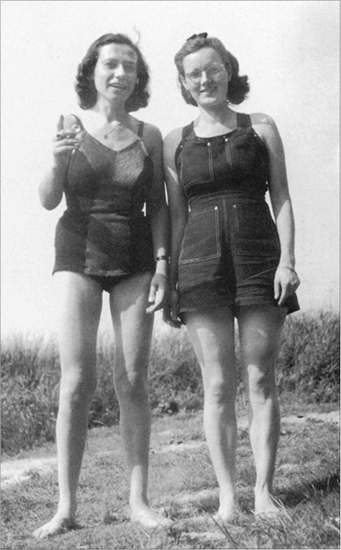

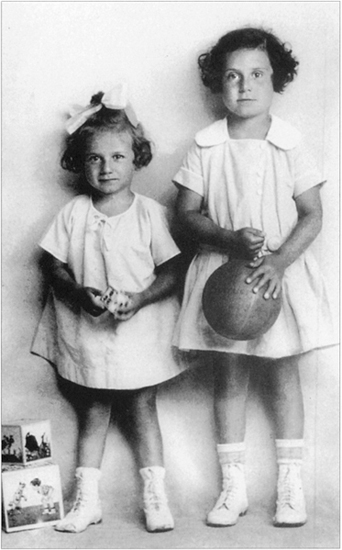

Felice (4) (left) and Irene (6) Schragenheim in 1926.

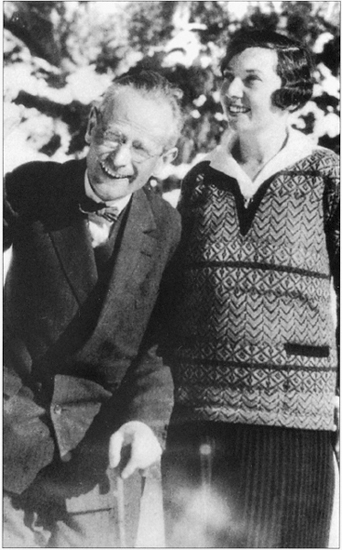

Felice’s parents, Dr. Albert Schragenheim and Erna Schragenheim, née Karewski, in Berchtesgaden, 1921.

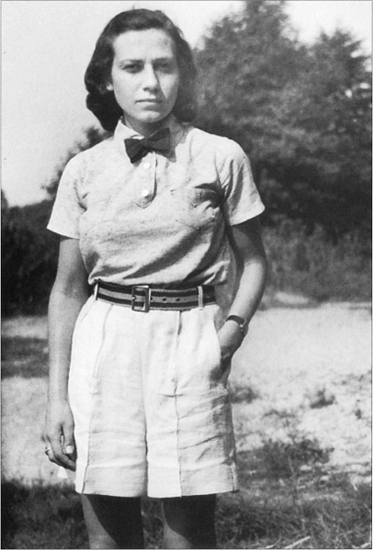

Käte Schragenheim, née Hammerschlag, Felice’s stepmother.

Felice’s grandmother Hulda Karewski, murdered in Theresienstadt.

Felice’s school class in Berlin-Grunewald, with teacher Walther Gerhardt, in June 1936. Felice is seated in the second row, left, and Hilli Frenkel, Felice’s best friend, is in the fourth row, left.

A medical certificate prepared by Dr. Israel Ernst Jacoby, dated 1939, indicating that Felice was “free from any infectious diseases” and therefore fit for emigration.

Günther Wust, Lilly’s husband, 1930.

Two notes. Top: from Aimée to Jaguar. Bottom: from Jaguar to Aimée.

Lilly with “bunker nurse” Herta, Reinhard, and Albrecht in front of Lilly’s building on Friedrichshaller Strasse, taken by Felice in the fall of 1943.

Lilly, Felice, and Käthe Herrmann, Lilly’s best friend, in Eichwalde, taken by Käthe’s husband, Ewald.

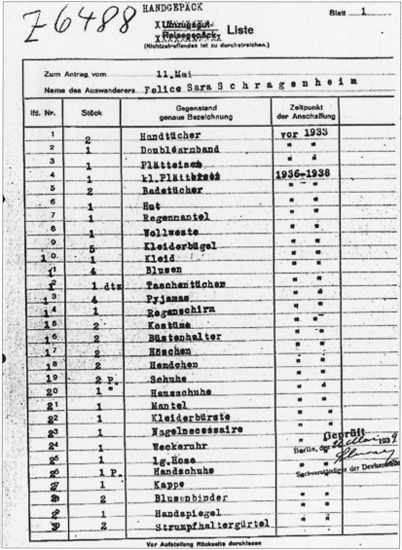

The list of belongings Felice wished to take with her when she emigrated, dated 1939.

The landing permit granted in 1939 to Felice by the Australian Jewish Welfare Society.

On May 9, 1939, the American Consulate General on Hermann Göring Strasse informed Irene and Felice that they had been registered on the German waiting list under the numbers 43015-b and 43015-c. “It cannot be stated at present when your case will be considered, but you will be notified of this in due time.”

In compliance with foreign exchange regulations, Felice applied on May 11 to the office of Berlin’s chief financial president for permission to take with her two four-piece silver place settings, a small napkin ring, a bracelet, a salt shaker, and a cuticle remover. To her application she attached a list of objects she wished to carry into emigration in her hand luggage. The items were consecutively numbered and listed with their year of purchase:

2 hand towels, 1 rolled gold bracelet, 1 iron, 1 small ironing board, 2 bath towels, 1 hat, 1 raincoat, 1 wool vest, 5 clothes hangers, 1 dress, 4 blouses, 1 dozen handkerchiefs, 4 pairs of pajamas, 1 umbrella, 2 suits, 2 brassieres, 2 pairs of underwear, 2 undershirts, 2 pairs of shoes, 1 pair of house slippers, 1 coat, 1 clothes brush, 1 nail kit, 1 alarm clock, 1 pair trousers, 1 pair gloves, 1 cap, 2 shirt ties, 1 hand mirror, 2 garter belts, 2 tins of powder, 2 pocket combs, 1 sewing kit, 4 pocket mirrors, 4 coin purses, 1 handbag, 1 pair overshoes, 1 watch pin, 2 belts, 1 bathrobe, 1 box gramophone needles, 1 pair walking shoes, 1 writing case with accoutrements, 5 ribbons, 2 pairs shoe bags, 2 collars, 1 razor, 2 tweezers, 1 small photo album, 3 lexicons, 6 books, 2 coupé cases, 1 suitcase, 1 hat box, 1 briefcase, 1 bath towel, 1 hat, 1 first aid kit, 3 gauze bandages, 6 pairs stockings, 3 bars soap, 2 pairs gloves, 1 cap, 4 wash pouches, 3 washcloths, 2 sponges, 2 combs, 4 brushes, 5 tubes lotion, 3 tubes toothpaste, 4 tins lotion, 4 packages sanitary pads, 4 packages laundry detergent, 2 veils, 4 packages absorbent cotton, 10 hair curlers, 3 bottles perfume, 1 bottle stain remover, 20 medications, 1 small box clip pins, 4 tins powder, 2 lipsticks, 2 pocket combs, 4 packs bobby pins, 3 packs shampoo, 1 pocket mirror, 1 wallet, 1 bottle ink, 1 pencil sharpener, 4 pencils, 4 boxes pencil lead, 2 boxes stationery, 2 fountain pens, 1 fountain pen case, 2 identification papers cases, 1 darner, 3 scissors, 3 belts, 2 boxes darning yarn, 12 pairs dress shields, 2 pairs shoe bags, 5 ribbons, 4 boxes safety pins, 2 pocket calendars, 2 typewriter ribbons, 1 stocking bag, 1 ring, 1 fever thermometer, 1 pair sunglasses, 2 writing pads, 1 shoe polish kit.

Following their father’s death, each of the two sisters received a wardrobe trunk for their emigration, outfitted with supplies to last for four years. On thinly lined paper Felice made list after list of clothing and objects that seemed absolutely necessary to her new life. On her English typewriter with its green ribbon she kept an account of the contents of the “gray iron military trunk,” one of three trunks packed with possessions in anticipation of the great journey, which was stored, for a fee of RM 4.20 a month, in the warehouse of the Hamburg carrier Edmund Franzkowiak & Co.:

Monkey, bread sack, 1 pair socks, 1 pair ski boots, 2 pairs ski gloves, ski suit, 1 pair galoshes, 7 sports shirts, 2 ski bands, 1 devil’s cap, 4 smocks, 1 apron, 3 gym shorts, 3 gym shirts, 2 bathing suits, 1 pair shorts, toy dogs, 1 wool blouse, 1 pair beach pants, 6 pairs socks, 5 pairs knee socks, 10 pairs stockings, 4 boxes sanitary pads, 4 packages absorbent cotton, 8 clothes hangers, 1 linen dress, 4 typewriter ribbons, 5 tubes toothpaste, 1 sanitary belt, 6 bars soap, 4 packages laundry detergent, 2 rolls film, 1 pair gloves, 1 pair wooden slippers, shoe travel kit, 2 pads stationery, 25 envelopes, 1 bottle Eu-Med, 3 bath sponges, 6 gauze bandages, 1 bottle Spectrol, 1 bottle Inspirol, 1 nail brush, 3 packages absorbent cotton, underwear, 1 dozen handkerchiefs, 1 dozen stockings, 1 iron, 1 Budko, 4 shampoos, 1 eyelash growth enhancer, 2 boxes badges, 1 evening bag, 1 tweezers, 1 white handbag, 5 pairs pajamas, 1 pair white shorts, 5 sets underwear, 2 brassieres, 2 garter belts, 1 brown winter ensemble, 2 pairs stockings, 3 blouses, 1 cloth, 9 clothes hangers, 5 winter dresses, 1 evening dress.

On May 30, 1939, the British Passport Control office requested a meeting with Felice to discuss her immigration to Palestine. The outcome of this meeting is unknown. On June 3 the “pupil” without a school, Felice Rahel Sara Schragenheim, was issued a passport valid for one year, stamped with a large red J. On June 9 the J. L. Feuchtwanger General Commercial Bank in Tel Aviv verified to the British Consulate General that debentures had been deposited to Felice’s credit. On June 13 Felice and her stepmother received a “landing permit” for Australia, valid for one year from issue.

THE TIMES ARE CHANGING—

Earlier our travel plans

Consisted of blue seas, palms, white sand.

Today our view is blocked by fate,

We no longer travel, we emigrate.

Those who once happily went away,

Now wish only that they could stay,

Without language classes, lists and such,

And if one must travel—then with the Baedecker touch.

Trunks that once to Biarritz went,

Now find that they are quite content

To travel to lands just recently found,

And therefore still as yet unbound

By polished manners, an overinsistence

On elegance, but for that, distance.

To find the promised land perchance,

One has to book far in advance.

And travel in the best of style,

On a luxury steamer—into exile.

[JUNE 16, 1939]

On August 7, 1939, an Australian visa was stamped in Felice’s passport. On August 9 the Charlottenburg branch of the Reichsbank informed Felice’s legal guardian, Edgar von Fragstein und Niemsdorff, that as many of Felice’s Palestinian securities could be sold as needed to exchange for two hundred Australian pounds, “so that your charge may demonstrate to the Australian authorities that she is in possession of the funds needed to enter their country.” On August 14 Felice was granted a two-year extension of the export permit for the belongings she had listed in May. Among Felice’s effects was found a copy of a reservation from the Middle European Travel Agency, made out to Käte Schragenheim and valued at 1,268.45 Reichsmarks, for passage on the steamer Australia Star, to depart London December 20, 1939, for Melbourne.

At the end of August a number of events occurred in rapid succession: On August 23 the Hitler-Stalin Pact was signed, and on August 25 the British-Polish Alliance Agreement; August 26 was the first day of mobilization; the Reichstag assembly was summoned and children were sent home from school. On Sunday, August 27, food ration cards were issued. Those distributed to the Schragenheims and the Hammerschlags by the concierge were stamped with a red J, which excluded them from all special provisions and from purchasing items of food that were not rationed. On September 1 German troops crossed the Polish border. France and England began to mobilize.

Gerd Ehrlich:

In Germany the war was taken very seriously, but I never witnessed any of the fervent patriotism that is said to have been so dominant in August 1914. . . . The outbreak of the war had a decisive influence on my personal life. In the first months of the war, Jews were treated almost as fully human beings. They weren’t totally trusted, of course, and once listening to foreign broadcasts was subject to severe penalties, their radios were taken away from them, for the sake of security. On the other hand, I was included in my building’s air raid precautions and was given the honorable post of fireman for the building. Jewish schools continued to operate, but increasingly had to consolidate.

After war broke out, emigration to the United States became more and more difficult, as foreign shipping lines no longer accepted German currency. Once it became clear that very few refugees had relatives who could pay their passage, the American Consulate began to require confirmation of payment from the shipping lines before it would issue visas. In addition, Washington, citing “misuse,” tightened the criteria required for an affidavit, so that only ten percent of those on German waiting lists were able to produce the papers necessary to receive a visa when their number finally came up.

At the end of 1939 there were still close to eighty thousand Jews living in Berlin. On September 1 an evening curfew was announced for Jews, from 9 p.m. to 5 a.m. in the summer months and beginning at 8 p.m. in the winter. In October apartment building residents were informed as part of their air raid instruction that “racial aliens” were not allowed in the cellar shelters. As of December, coffee and sweets were made unavailable to Jews. Large red signs were posted at all businesses and markets, which read, “Purchases by Jews to be made only after 12.” Aryans seemed unaffected by this. Despite the rising cost of food and beverages, the decline in the quality of beer, and the food substitutes, cafés and restaurants were booming. Nor did the darkness prevailing on Berlin’s streets at night, allowing city-dwellers an unusual view of the stars, keep people from swarming in droves to movies, theaters, and concert halls. Everyone was seeking diversion and a way to spend their money, for there was no sense in saving it. Women were advised to seek the company of a man, for since the outbreak of war the number of “crimes against morality” committed under the cover of darkness had risen drastically.

On January 24, 1940, Felice’s sister celebrated her twentieth birthday.

THE WAY IT IS . . .

(For Irene)

When we were small, getting to know each other,

We tried, with gestures and with words,

To hurry and be like Father and Mother,

Like the so-called adults we saw and heard.

Nor could we avoid it, time went by,

We got older—each remained alone,

And finally, even without the disguise

We appeared as “people” in everyone’s eyes.

But that’s no reason to whine and moan!

The world is like a park in April,

Benches freshly painted, all in line.

You sit down more often, clueless and still,

And much too late you somehow feel

You look a bit funny from behind.

That is a bother, it is true,

But it would be mistaken to block

From mind the sun that is shining through,

When, from one too many benches, you

Have truly become a bit too blotched . . .

[JANUARY 24, 1940]

The war gradually began to interfere with daily life. Rationing was extended to include restaurants, the shops slowly began to empty of goods and the black market flourished. As of February 1940 Jews no longer were eligible for ration coupons for clothing. On February 28 Chicago surgeon Walter J. Karsten once again signed a notarized affidavit for his niece Felice: “We are anxious to welcome Fräulein F. Schragenheim into our home, so that she may help out in our residence and in our practice.”

But the quota for Germans entering the United States had almost been filled. And German refugees from the transit countries of France, Belgium, the Netherlands and England were favored over others—a courtesy that America granted to its allies.

Gerd Ehrlich:

In the spring of 1940, Berlin was suffering a major housing shortage. Many people from the western regions whose presence wasn’t exactly essential were coming to Berlin. An elderly aunt of ours arrived from Karlsruhe. Several minor air attacks, which at the time seemed major enough to us, destroyed a few buildings, and this resulted in “consolidation,” which began with the Jews, of course. We had a seven-room apartment, which four of us shared with a girl. Slowly we had to take in more and more people, all of them Jews, naturally. By the time we were forced to move out, there were fourteen of us living in the same apartment. At first we were told that Jews could live only in so-called “Jew buildings,” to be vacated by the Aryans living there. This plan was never carried out, however; instead, Jews had to vacate Jewish buildings if some party boss or other liked an apartment there.

In March Olga Selbach received her secondary school diploma.

GRADUATION CERTIFICATE

(For Olga)

For you the curtain has now rung down,

Complete with applause, critique, stage fright.

You’ve got your diploma and, in our view,

You’ve grown a good deal in our sight.

Student of medicine—quite a goal!

Requiring a strong dose of purpose, perhaps.

(The fact that you dropped your diploma today

We’ll just let slide as a minor relapse.)

The family, Olga, expects something of you.

School was just the orals.

And between the two of us I’d advise,

Not to rest on your bed of laurels . . .

Equally matched we started the chase.

But then they checked the tangibles.

I had the misfortune to be erased,

But you’re to cultivate the frangibles!

You’ve overcome so many obstacles—

Latin, and even your morning chores.

Now you’ve reached your first goal

We look at you and are proud.

[MARCH 1940]

Shortly thereafter, Olga found a position as a governess in Eastern Pomerania. “Are you crazy, why would you want to go there?” Felice scoffed.

On May 10 German troops crossed the Belgian border. “The battle that begins today shall decide the fate of the German nation for the next one thousand years,” Hitler declared.

Following a rather restrained reaction to the launching of the western offensive, a series of rapid victories quickly elevated the country’s mood again. The press constantly urged Berliners to “return to theaters, movie houses, concert and music halls.” The winter had been a hard one, with the flow of supplies so critically disrupted that schools had to be closed from January to March. Warmer temperatures brought on a mood of abandon that may even have had its effect on Felice. To compensate for the obstacles confronting her in life, she had a series of constantly shifting love affairs. Felice felt drawn to “prominent” people, those who enjoyed the spotlight she herself was denied. The actresses she fell for were usually quite a bit older than she, and had been introduced to her by her stepmother, who traveled in film circles.

At some point during the second half of 1940 Käte Schragenheim must have sailed for Palestine. It appears that Felice decided at the last minute not to accompany her stepmother. The prospect of traveling to Palestine with Mulle must not have appeared very enticing. And as her stepdaughter planned to go to her Uncle Walter’s in America, Käte Schragenheim probably departed somewhat reassured. But it may have been the draw of Mutti that convinced Felice to stay. She spent a wonderful time with the Selbach family at “Forst,” Mutti’s summer cottage in the Altvater Mountains, with her white Scotch terrier, Fips, always in attendance. “Forst” was a perfect place to escape the Nazis, but above all it provided a feeling of security and warmth that she missed, having lost her own family at such an early age.

Mutti was an extremely important person to Felice at eighteen. She was part mother and part unattainable object of desire, whom Felice was obsessed with and in constant fear of losing. Felice’s courtship went unreciprocated, though Mutti was flattered nevertheless when Felice arrived with flowers and hung on her every word. Each time Mutti took Felice tenderly in her arms, as she did her daughters, Felice believed that her dreams were finally coming true. But this moment inevitably was followed by a gruff rebuff: “What in the world are you thinking?”

“Must you be that way? Get it out of your head, you’re crazy,” Felice was warned often enough by Olga and her sisters. But Felice couldn’t get it out of her head, and always started up again with the same thing.

Christa-Maria Friedrich:

One day a wood-carved Madonna was suddenly standing on Felice’s desk. I asked her what that was supposed to mean. “It’s pretty,” she said, “a mother with child.” I think there was a lot more sadness and sensitivity in her being, hidden behind her tomboyish cheerfulness, than one would at first presume. Her poems are evidence of that. They have the same tone as Erich Kästner’s and also Mascha Kaléko’s poetry. Such a mocking, satirical mask was evidently necessary in order to conceal the delicate, sadness-prone soul.

YOUR LETTER

Perhaps it was not at all fair

To read your letter lying there.

But I was destined to someday find it,

And as in some heavy and horrible dream

To see in black and white what seemed

Improbable. I didn’t want to know it.

The higher you stand the farther you fall

Believe me, I fell after reading it all

I cannot escape your tone

Nor its refrain, no matter what.

It’s all for naught.

And I am alone, alone, alone.

You said it quite clearly, and with it destroyed

My one slim chance at some small joy.

You must have felt it, this betrayal!

I was prepared to serve and love you,

But now I’m just a vagabond,

Who must stand outside the door . . .

[AUGUST 3, 1940]

Three days later everything appeared to have changed:

FALLING STARS

A shooting star lights up the sky.

It’s meant to be, they tell the little ones,

Shooting stars carry their fate within,

That little one there has done much good.

Life gives and takes, and life falls mute.

One often stands at the window at night,

Asking and doubting and losing sight

Of the path. The little star showed me mine.

A bright star falls and lights up the night

And I feel, long hours having passed,

That I have found a way out of my plight

The little star has returned you to me!

[AUGUST 6, 1940]

Is this poem, which indicates a reconciliation with Mutti, a clue perhaps to Felice’s foolish decision not to accept the “engagement” mentioned in a letter she wrote to her friend Fritz Sternberg? The journalist, whom many believed to be Felice’s lover, answered her with concern on August 31: “What really displeased me was the way in which you handled the engagement that was so generously offered you. I very much would like to hear from you your true reaction to it. It is not something, after all, that one can disregard as easily as you did in your letter.”

Is “engagement” a code word for Käte Schragenheim’s departure for Palestine? “Käte cannot at all comprehend why Lice wanted to stay in Berlin and how it came to that,” Felice’s sister Irene would write from London in 1949.

The situation of Berlin’s Jews worsened in the summer of 1940, once the “Battle of Britain” commenced on August 13 and people increasingly were wrenched from their beds to the sound of wailing sirens. As of July, Jews were permitted to buy food only from 4 to 5 p.m., and could sit only on those park benches marked “For Jews Only.” In addition—the biggest blow—their telephone lines were disconnected and they were given until the end of the year to turn in their telephones. On September 15 Fritz Sternberg prepared Felice for her return to Berlin:

I imagine you joyfully rushing up the steps of your grandfather’s house, greeting your dear relatives with a hammerlock of an embrace [a pun on the Hammerschlag name] and then forgetting yourself and reaching for the telephone. Do not, oh do not do so, for you will find its beloved place empty. It has been carried to its grave. You will hear that cherished sound no longer, nor will you be able to convoke it. It will be still, unsettlingly still. While there, where cows, goats, chickens, and the produce thereof delight you despite the hail, snow, and rain, animal life here, minus the produce of course, will not do the same for your mood, because what is essential is missing: the telephone you reach for five times a day.

This situation has led to strange developments. I’ll cite you an example from my own experience. The phone jangled recently at my workshop. An electric spark leaped toward me and sure enough, the call was for me. Lupus was on the line, inviting me to visit him and his wife. I accepted happily, mainly because an invitation by telephone is one of life’s rarities today. So I hammered out a flat and ran off. Unfortunately I arrived fifteen minutes later than agreed upon in the heat of the moment. No Lupus, door locked. I stood there and whistled to the point that I loosened my last remaining baby tooth, but nothing stirred above. Half an hour later I crept home, sad and contrite. The next morning I received—together with your letter, for which I thank you—a card with the following message:

Dear Fritz!

Yesterday, Thursday, I waited at the door from 9:15 until almost 9:40. My wife would have gone to bed had she not been anticipating your visit. Is it right to keep an old man standing at the door for so long? Is it chivalrous to keep a lady waiting? Get an appointment calendar, mend your ways, and then let us hear from you.

Best Wishes,

W.

In consideration of the actual circumstances, you must admit, in all fairness, that these reprimands turned things on their head somewhat. Wife not in bed, old man at the door, appointment calendar . . . I must say that’s really taking it a bit far. But such things take place these days, and you shall now experience them for yourself. For I scarcely reckon that my introduction to the telephoneless age truly has been able to communicate to you such insight that you will be spared the emotional distress I myself am still experiencing.

Following this particularly difficult sentence, I shall close. You will be here at the end of the week, then you can write and tell me when we may see each other. Out of this will develop a lengthy correspondence, for it is not to be assumed that our respective available appointment times will be perfectly suited to one another. (Wife in bed, wife not in bed, old man has no time, old man at the door, wife back in bed again . . . there’s no end to it.)

I will be happy to see you. But when, when??

At the probable urging of her uncle Walter, Felice continued her attempts to emigrate to the United States. But the signing of the Franco-German cease-fire on June 22, 1940, had made this even more difficult. U.S. ships were able to dock only in British and Portuguese ports. Until the end of 1941 most emigrants would pass through the port at Lisbon, and passage by ship from Lisbon had to be booked nine months in advance. Still attempting to resolve the “Jewish problem” through emigration, the Nazis shipped refugees to Lisbon and to the Spanish seaports in closed trains. The greatest hurdle to be overcome was the Americans’ fear of a “fifth column,” disguised as refugees. Lacking a legal basis for the tightening of controls over the issuance of visas, they resorted in June 1940 to foot-dragging:

“We temporarily can slow the number of immigrants to the United States, and as good as bring that number to a standstill. This will be possible if we instruct our consulates to place all possible obstacles in the applicants’ paths, to require additional information and establish various administrative measures, which will serve to delay and delay and delay the approval of visas. At any rate, this will be possible only for a short time.”

On June 29 the State Department instructed its consular officials by telegraph to go over in the greatest detail all applications for lengthy stays in the United States, and to freeze the issuance of visas in the case of the “slightest doubt.” “The telegrams bringing immigration to a virtual standstill have been sent,” the State Department official in charge noted in his diary with satisfaction.

American historian David S. Wyman cites an example of this inhuman delay tactic, which Felice’s grandmother, Hulda Karewski, may have experienced as well: Beginning in 1939 a Jewish refugee working as a physician in the United States attempted to bring his sixty-three-year-old mother from Vienna to the United States. After waiting a year and a half for her visa, her name finally appeared at the top of the list in March of 1940. But at that time her passport was in the possession of the German authorities. After it was returned to her she was informed by the American Consulate that new quota numbers would not be issued until the beginning of the next fiscal year, starting in July.

In August she was informed that everything was set, and that she needed only to undergo a medical examination, scheduled for the end of that month. To her son’s horror she was notified in September that her visa had been denied, because the papers submitted by her sponsors were incomplete and her health left something to be desired. Finally, friends in the United States succeeded in getting her papers reexamined, and they were approved in March 1941, this time without mention of her health. She received her visa and joined her son, a positive turn of events that Hulda Karewski would never experience.

On January 15, 1941, from Chicago, Uncle Walter sent the American consul in Berlin a notarized copy of his 1940 tax return, and pressed for an answer as to when his niece would be issued a visa. Walter Karewski had no children of his own, and it was his greatest wish to bring both of his nieces to America. Karewski had had to repeat his medical exams in the United States, and was proud to have established himself as a gynecologist in so short a time. On January 17 he cabled Felice: DOLLARS 1000 BOND WIRELESS AT CONSULATE GO OVER IMMEDIATELY HOW ARE TRANSPORTATION TO AMERICA WHO PAYS TICKET = WALTER.

On February 11 American Express sent to the American Consulate General verification of passage booked on the Marques de Comillas, of the Compañia Transatlantica Española, to sail from Bilbao to New York on June 10. On February 19 Felice signed an application addressed to the district mayor of Berlin-Wilmersdorf and to the Finance Office in Charlottenburg-West for issue of certificates of fiscal nonobjection for persons who intended to emigrate. These were sent to her on February 22: “Valid until recalled!” On February 20 her guardian, Edgar von Fragstein und Niemsdorff, declared himself in agreement “that the passport issued to my charge for the purpose of emigration be handed over to her directly.” Felice’s passport was extended for one year on February 26. On February 28 (still Number 43015-c) she was to appear at the consular section of the American Embassy between 10 a.m. and 12 p.m., to receive her visa. “It lies in your own interests not to make any definite preparations, the dissolution of your household, etc., for example, before you are in possession of your immigration visa.”

Felice was assigned Quota Immigration Visa Nr. 23989, valid until July 17, 1941. The inky impression of her ten fingerprints was attached to the visa, in addition to a declaration of consent signed by her guardian, a certificate of good conduct issued by the police, two notarized certificates of good conduct signed by Harry Israel Hammerschlag of Berlin-Halensee, sales representative, and Fritz Israel Hirschfeld of Berlin-Charlottenburg, photographer. Felice, whose “race” was given as “Hebrew,” was 5 feet 3 inches tall and weighed 113 pounds. Her port of embarkation was Bilbao. On February 26 American Express certified that its New York office was holding three hundred dollars at Felice’s disposal for purposes of passage.

Beginning in July 1941 the first Jews from the “Old Reich” were deported to Lodz, Kovno, Minsk, Riga and the Lublin district. On July 1 the Spanish Consulate in Berlin issued Felice a transit visa, valid until February 26 of the following year, for her trip to the United States on the Navemar, to depart July 15, 1941. Felice informed the American Consulate on July 12, “according to regulations,”

that my immigration visa to the USA will expire on the 18th of this month without my yet having been able to make use of it.

It was issued to me on the basis of my reservation of passage on the ship “Marques de Comillas,” which I booked through the American Express Company. As this ship did not sail, I rebooked passage, and since then have made four further bookings through American Express, which were not met partly due to the temporary closing of Portugal’s borders, and partly to a lack of ships.

I finally booked passage on the “Navemar,” but it too postponed its departure date and still has not set a new one, so that I no longer may make use of my visa.

I would be very grateful to you if you would notify me of my chances for a possible extension of my visa.

An answer arrived posthaste: “Re your inquiry, we must inform you that the handling of matters concerning the issuance of visas has been suspended until further notice.”

Diplomatic relations between Germany and America had ended. German consulates were closed on July 10, 1941. Three days later Germany responded with the demand that all American consular officials leave those areas of Europe under Nazi control, dashing the hopes of thousands of refugees. Of the thirteen thousand Germans who emigrated to the United States between July 1940 and July 1941, only four thousand arrived directly from Germany. This was an eighty-one percent decrease in the emigration quota compared to that of the previous fiscal year.

For Felice there was one last glimmer of hope on August 21. The “Emigration Department” of the Reich Association of Jews in Germany informed her that she would participate “in the twenty-second special transport of Jewish refugees, agreed upon by the agencies responsible,” to leave Berlin for Barcelona on August 26. “We request that you obtain an emigration visa through Neuburg/Mosel.” But by the next day the cancellation already had arrived: “We regret to inform you that your scheduled departure cannot take place, as the emigration of women and men between the ages of eighteen and forty-six is forbidden. We leave it to your discretion to contact us concerning this.”

At this point Felice may not even have been in Berlin, for on August 24 Hans-Werner Mühsam, a friend, wrote to her at the “Forst”:

My Dear ’Lice Fice,

I had come to the—for my part—depressing conclusion that, captivated by some babbling brook or some captivating babbler, you had forgotten me, when today—like the proverbial deus ex machina that leaps out at me from all the consulates where I proficiently go about my expulsion—your kind card arrived. I can only say that when it comes to you I am an outspoken individua-list (individua, envie, envy). How I would like to saw wood with you, and sleep with you, the former passion I seem to have inherited from our erstwhile Kaiser, to say nothing of blueberry-picking and enjoying a nip now and then! Don’t you have a bit of room for me, even at the danger of it being at your vestal breast? In time of war one must tolerate everything, and I would be so happy with you far from civilization, forgetting the blessings of the Fontanepromenade [location of the Employment Office for Jews]. Aside from the fact that I have endured a house search and hours of interrogation (due to a denunciation), that all my preparations for emigration collapsed with the closing of the consulates of the duodecimo states of Central America, that Rosenstrasse [location of the Jewish Welfare Agency] has suddenly shown an interest in me (unrequited), and that my stomach is in revolt as a result of too many rationed fruits, I am faring splendidly, at any rate much better than I will be in the fourth year of war, 1943.

Fritz Sternberg wrote to Felice as well, addressing her as Stift, or “apprentice,” a nickname her friends gave her when she was taking photography lessons from Ilse Ploog. The letter is undated and is apparently in answer to her question of whether or not she should remain at the “Forst”:

Stift,

Knowing you as I do, you simply want a confirmation of a resolution/decision you have already come to. You want me to say: Stay there, keep drinking milk straight from the cow, laughing without civilization and sleeping without orthography. Am I right? You need nothing more than a little encouragement. If I knew for certain that a certain visit had not been paid to your grandparents on your stepmother’s side, and if I knew for sure that they would not be receiving anyone in the foreseeable future, I would gladly grant you that favor. But unfortunately God did not bestow upon me the gift of prophecy, and so I can only say that there is, of course, a certain risk involved. I assume that you reported your change of address—then the risk would be slight, perhaps even nonexistent. (In that case I would then agree to an extension without the slightest hesitation.) But should that not be the case, and should they receive a visit—which could be anticipated, but then again is not certain; possible, but not probable—the situation could become unpleasant for both you and your foster parents. So I can respond to your precise question only with a highly imprecise answer: Hmm, well, let’s see, well, then . . .

Now that I sufficiently have beat about the bush placed before me, I come to the second part of your letter. But first you must explain a few things. What, in good German, does it mean that you don’t think much of worrying and thinking about yourself??? And in equally good German, what do you mean when you say that this year you are having thoughts similar to those of last year? What is the unpleasantness that awaits you in Berlin? Does all of this have some inner connection? What is it that is plaguing you and “clouding” your brain? It seems to me you’ve gotten hung up in some exceptionally dark thoughts. You know you can talk to me if you have something on your mind, or anywhere else. I often had the—perhaps false—impression here that there was something you wished to talk to me about. So, if you want to and are able—shoot. After all, I am—hopefully you will notice how my chest swells—at the mature age at which one either has or has not attained wisdom. I leave it to you to put that to the test.

In March 1941, twenty-one thousand Berlin Jews over the age of fourteen were assigned to forced labor. Following the June 21 offensive against the Soviet Union, Jews no longer received supplementary vouchers for soap, and ration cards were required for “fresh skim milk,” which Berliners called “Aryan skim milk,” because non-Aryans had to forgo this luxury.

In July the Nazi party leadership decided to prepare the “technical, material, and organizational” preconditions for a “comprehensive solution to the Jewish question.” The Reich Law Journal published a decree stating that as of September 17, all Jews from the age of six years on must wear the “Jewish star.”

Gerd Ehrlich:

We chuckled in disbelief at this piece of bad news, related one Sunday morning by my future stepfather. But when Benno then read the law aloud, my mother immediately began talking about “taking her life,” and it took a great effort to calm her down again. And in fact, a classmate of mine poisoned himself that day, and he was not the only one driven to despair. Our distinguishing mark, which soon bore the sad epithet “pour le Semite,” consisted of a yellow Star of David inscribed with the word Jude [Jew]. This “badge” had to be worn visibly on the left side of the chest, sewed securely onto the cloth.