FOUR

On April 2, 1943, when Felice asked if Inge would object to her spending the coming nights with Lilly, who was still weak from her visit to the hospital and didn’t want to be alone with her four children, Inge found this an excellent idea. Felice had lived for six months as a “U-boat” in Inge’s parents’ apartment, a situation that was in no way safe, and Inge felt it was high time that Felice found somewhere else to stay. Nor was she safe any longer at Elenai’s, whose half-Jewish mother had been sentenced to ten months in jail for railing at Hitler, and was in the Moabit prison. With bombing attacks on Berlin on the rise, the situation was becoming increasingly precarious. Inge usually stayed in the apartment with Felice when the alarm sounded, but once going down to the cellar became imperative they would be forced to come up with a credible identity for Felice, for their building was full of Nazis. If it were discovered that Father Wolf was hiding someone who had gone underground, he would be sent to a concentration camp for sure. Felice would be much safer in the apartment of a respectable soldier’s wife; she couldn’t do better, in fact. Inge knew nothing yet of the feelings that Lilly and Felice had developed for each other.

“So how shall we manage this?” Inge asked. “You don’t have food coupons.” One could not exist in this fourth year of the war without food coupons. “Just tell her you have a neighborhood grocery in Friedenau, near the Selbachs’, where you always buy your rations, and that you don’t want to give it up. Say, ‘I go there often,’ or something like that. And then when I have to shop for the Wusts, I’ll just set aside for you some of what I buy. Wust gets an amazing amount of food for her four children, she won’t even notice it. They can’t eat all of it as it is.”

And that is how it went. Inge got hold of some suitable packing paper and after she bought groceries she would stop on the landing between the fourth and fifth floors and repack some of the rations for Felice. If there was a half-pound of butter for the children she put aside a quarter-pound for Felice.

“I went shopping today,” Felice would say, and everything, literally, went smooth as butter.

Felice, too, was pleased with the new arrangement. She would tell Lilly that she had to go to Babelsberg, and then spend the day at Elenai’s, or at Mutti’s in Friedenau, or would wander back and forth from one to the other, always in search of new information that would tell her whether her situation was getting better or worse. Elenai recalls one day when Felice made fourteen visits. But Felice also enjoyed the security provided by living in the apartment of a Nazi woman. It was wonderful not to have to hide, to live with a real family, and in Schmargendorf to boot, close to Auguste Victoria Strasse where she had spent her childhood. This could also, of course, be a source of new danger, for it was possible that she would be recognized and denounced here. Moreover, it was clear that mothers held a special attraction for Felice—especially if they had a charming freckled face like Lilly’s. Under Lilly’s care Felice was able to forget for a while that she was not even supposed to be alive. Lilly’s devotion and the children’s affection made up in part for the indignities she had been subjected to for a decade now. When Albrecht ran toward her crying, “Hice, Hice,” in his high little voice, her eyes filled with tears of joy. She had not felt this at home and secure since last summer, at the “Forst.”

Christa-Maria Friedrich:

I don’t know when it was that I ran into Felice on the 176 bus. When I had seen her earlier she had been wearing the yellow star, but now she wasn’t. She noticed my questioning glance to her left breast. In her characteristic happy, mocking way she said, “You’re looking for the star, aren’t you? I’m not Jewish anymore.” “What?” “Yes, I’m an Italian guest worker. I learned Italian in six weeks. I’m now working in a factory.” “And what if you run into N.?” (N. was the only Nazi girl in our class.) “I did recently, in the subway.” “And what happened?” “She didn’t see me and at the next stop I changed cars.” Sometime around then she got her visa. I was with her and the rubbed-varnish furniture one more time. We wanted to say goodbye but she simply did not let herself be sad. About four weeks later I ran into her again somewhere on the street. I was truly shocked. What had gone wrong? Felice was more contemplative than usually. And then she told me that she was on the ship but she simply couldn’t leave. She said she just had to stay in Germany. “And what’ll you do now?” I asked, concerned. “Now I’m staying near Roseneck and I take care of four children.” I didn’t ask for her address.

At the beginning of the year Felice, with the help of her underground friends, paid two thousand Reichsmarks to secure a chaperone ID issued by the Reich Central Office of the “Country Stays for City Children, Inc.” This rather simple document, without photo, identified Felice—under the name Barbara F. Schrader—as a “chaperone for children on domestic outings,” valid until April 1, 1944. The clumsily filled-out pink authorization never would have passed close inspection, for Felice had filled in the date in her own hand, whereas the name “Barbara F. Schrader” had been written by Inge. But if one were picked up it was better to have some kind of ID than none at all.

Gerd Ehrlich:

My group consisted of Walter, Ernst, Lutz, Herbert, Gerdchen, Günter, Halu, Jo, Fice (the only girl), and myself. In addition to this core group there were other friends who met with us on an irregular basis, and with whom we exchanged experiences.

We had successfully overcome the initial difficulties, but the more experience we gathered in our new life the more we realized that major problems were to come. And we encountered difficulties finding housing soon enough. It was not always possible to stay with good friends who were Aryans, for though they meant well there was almost always some member of the family who opposed the plan of hiding one of us. Halu was the first to come up with the brilliant idea of renting a furnished room by the day. There were various “accommodations agencies” in Berlin, so one day Halu went into one of them and paid the prescribed fee, saying that he had had a fight with his family and wanted to spend a few days away from home. He was given a list of addresses where there were rooms to let, and so he rented one of these furnished rooms and told the landlady the same story. When the good woman mentioned that he would need to register with the police, he said he was registered as it was in Berlin anyway, and didn’t want to change his address due to the enormous difficulties with ration cards and ministry of defense forms.

Once Lutz went underground our organization arranged for him to go to a branch of the German Red Cross as an unpaid volunteer. With his usual aplomb, he soon gained the confidence of his superiors, and using the name “Fred Werner,” he was left to work independently. As his job was to take care of correspondence, it was not long before he had a collection of official stamps on his desk, and one day Lutz also came into possession of a large block of blank DRK [German Red Cross] identification forms. He quickly added to this a set of stamps and a few pieces of letterhead stationery, and that was the last the DRK saw of him. We found out that a warrant was even being circulated for his arrest. So he was the first of us forced to make his way to Switzerland.

But we had what we needed for the time being. All of a sudden we all had advanced to the position of consultant, or sub-department head or interpreter. Each of us was in possession of an impressive ID, identifying us as good Germans. The documents would never have passed a serious check by the Gestapo, of course, but they served splendidly in the case of a street roundup or for the eyes of a curious landlady.

Gerd Ehrlich was one of the few Jews living underground who had no financial worries. There was always someone willing to buy one of his deceased father’s valuable rugs, stored at friends’ homes, and so he found himself in the fortunate financial situation of being able to assist those of his friends who were less favored. And if one had money and connections it was not at all difficult to buy food coupons. Once in a while someone would turn off the counter of the food coupon machine and let it run, and the group suddenly would have an entire stack of coupons they would have to use up in a very short period of time.

Whenever Gerd left the house he carried a forged military photo ID made out to Gerhard Kramer in one pocket of his jacket and—as a passable speaker of French—a Belgian foreign worker’s permit in the other pocket. Foreign workers were checked by the Gestapo but not by the army, so he simply had to remember not to get his pockets mixed up.

The forging of identification papers was achieved in the following manner: First, a future ID holder was located whose outward appearance—hair and eye color, height, age and identifying marks—matched as closely as possible the description on the ID. A new photo was then attached using a special device, and half of the official stamp was copied onto the photo, a piece of specialty work that came at a high price unless a sympathetic colleague could be found to do it. Gerd Ehrlich’s circle finally came in contact with a “half-Aryan” graphic artist who was a master in the field, but he unfortunately lived far outside the city.

Identification papers had to be located first, of course. One method particularly favored in the summer was to go to the Wannsee, where pieces of clothing left carelessly in the grass and sand could be searched while their owners were swimming. In a desperate attempt to match the personal description on one such document, someone once actually chopped off his own finger. Then the documents had to be taken to the graphic artist and picked up again. Among Felice’s responsibilities in the “organization” was to carry out this sort of task. She was always asking Lilly to accompany her to various places where she met with people she did not introduce Lilly to. Sometimes it was at the Haus Vaterland on Potsdamer Platz, at other times they took the Number 51 tram from Roseneck to Pankow, to the Schmidt Photo Shop, or they would ride the S-Bahn, the suburban train, to Babelsberg, where Lilly would wait for Felice in a café. Once, Lilly watched from a safe distance as Felice whispered with a pretty young woman in a gun shop on Taubenstrasse and then slipped a piece of paper into her pocket. Lilly didn’t ask questions.

“This has nothing to do with you. These are things you shouldn’t be seeing,” Felice said, after Lilly discovered a picture of Elenai stepping out of the bathtub nude, drops of water glistening on her skin. “We make these things for soldiers.”

Lilly had no further comment, merely noting that the girls were having pornographic pictures taken by Schmidt the photographer. It was more likely, however, that he too was involved in forging documents for them.

Elenai Pollak:

I met Schmidt one day, I no longer recall where. He thought I was interesting and good-looking, and asked if he could take some nude pictures of me. He wanted to enter them in a photography contest, and with my looks he had a good chance of winning, he said. This didn’t surprise me greatly; I found it quite understandable, actually, and so I said, well then, if you wish, take them. He absolutely insisted on shooting me in the bathtub under the shower. And because our bathtub at home was dreadful, he invited me to his place. There was another man there when I arrived, he seemed a clever sort. So I said to him, tell me, who are you, actually, and what do you do for a living? I’m a pastor, he said. To which I replied, well, I’m certainly in strange company, when pastors start taking nude photos of girls. Very well, then, whatever. I was adventuresome and had a surplus of energy. Life and my imagination went on. It was a diversion, something different for a change. Inge still has the photos of me.

In one of the portraits that Schmidt made, Elenai is wearing her long black hair loose and flowing, and staring dramatically into the distance. Otherwise she never wore her hair down. On the contrary, she did her utmost to appear less exotic and striking. Her mother was obsessed by the thought that Elenai was recognizable as a Jew even from a distance, and constantly afraid that something would happen to her. Felice and Elenai tried to figure out how they could “Germanize” her appearance, and arrived at the grandiose idea of fixing Elenai’s hair in the “Gretchen” style, with a braid wrapped around her head and fastened into a knot at the back.

Lilly continued to write monologues to Felice on the yellow-and salmon-colored army-issue postcards—the only affordable stationery—even when the lovers were separated for only a short period. Inge’s presence during the day, and the flurry of activity necessary to maintain a household with four children, with rations becoming ever scarcer, left the two women little time for any prolonged communication. A few quickly penned lines, an “I love you” on a scrap of paper discovered in one’s purse when shopping, in the toothbrush glass or under a pillow, helped to compensate for hours spent in longing. Felice continued to disappear, even overnight, as she did at the end of May, after Lilly already knew Felice’s true identity:

Another night alone!

And what a night I had! I want you so, it hurts. It hurts terribly. I love you! I fell asleep, but then I had such lovely dreams that on waking I was terribly disappointed that you weren’t lying next to me. I had to bite into my pillow so that no one would hear me. All I can think of is: Felice! I’m so afraid that one day soon you will love someone else. Please don’t be sad when I say this, but you have changed me totally. I am no longer myself.

I have your picture here in front of me! When I think of the years I have wasted! Felice, please don’t leave me alone, please take me with you! I know that would mean that I would leave everything and everyone behind, but what does that matter if you love me! We belong together. You know that you’ve brought my world crashing down around me (nor, God knows, am I sorry)—my whole world. And now you must protect me. Will you be able to do that? Do you love me? I want to live in your world, even at the cost of great pain. Your love alone will help me through. It’s a great responsibility! Are you anxious? Are you afraid? Can you answer me?—I’m waiting for you . . .

But the moments Lilly spent in the agony of love and fear for the future were more than compensated for by the joy of everyday life lived with her beloved. She felt like a window had been thrown wide open and there was so much sun streaming into her life that she was almost blinded. As long as Inge remained in the dark about what was going on, it was fun to run the household together. Felice and Lilly had to try terribly hard not to give themselves away, for they had decided not to cause Inge hurt. Neither Inge nor Felice were model housewives, it was true, despite the marvelous cooking course that Felice had taken in her sixth year at school. But when the two of them washed dishes and sang “Little Marie sat in the garden weeping, her slumbering child in her lap . . . ,” one more off-key than the other, Lilly, who was raised on Schubert and Brahms lieder, got a knot in her stomach. She then had to stop and take a deep breath, amazed at the miracle that this girl, Felice, hounded as she was, had brought to her life. Inge fell silent at the sight of Lilly smiling at them indulgently. If she envied Lilly anything it was the clear and strong singing voice with which she sweetened her daily chores.

Elenai Pollak:

Naturally we found it amusing that Lilly perked up so much in our circle. We had our own missionary tic, of course. A woman like that can indeed become “different,” we thought, maybe we’ll do it. And there was empathy involved as well, on Inge’s part at least. We, too, had entered a world we had never known before—a petty-bourgeois Nazi milieu, with a woman who suddenly wanted to come over to our side. That was a challenge, of course. We were all watching to see how she would react. We had adventuresome natures and found what was happening exciting: to us and to her, alternately.

It was in May 1943 that Inge made the acquaintance of Gerd Ehrlich.

Gerd Ehrlich:

One evening Ernst and I were to meet Felice in a pub on Nollendorfplatz. She arrived in the company of another young girl, who had stunningly beautiful brown eyes. Her name was Inge W. and she knew all about us and our situation from Fice. After I had taken care of “business” with Fice, I turned my attention to the lovely Inge. By the time the evening was over we already were good friends, and had arranged a rendezvous. Inge was my only love during the time I spent as an illegal. . . .

The following Saturday Inge and Fice invited my friend Ernst and me to the Wust residence. This Saturday was the first in a long line of Saturdays I spent in the apartment near Roseneck. I passed many a pleasant evening there in the company of the women and my friends; we even stored some of our materials there. [Frau] Wust was known in her neighborhood as a true Nazi. It was our (positive) influence that converted her. Of course, in order to be of even greater help to us she remained a loyal follower of the Führer on the outside.

Gerd Ehrlich, Walter Johlson, nicknamed “Jolle,” and Ernst Schwerin soon became welcome guests in Lilly’s home. Gerd was living at that time in “Aunt Ilse’s” groundfloor apartment, which could be seen from the street, and so he had to leave the apartment early each morning and not appear on the weekends at all. The question of where he was to spend Saturday nights often arose. Despite Inge’s warnings about Lilly, the couch in the Friedrichshaller Strasse study served nicely.

“Great,” Gerd had responded to Inge’s argument that Lilly was a “good Nazi.” “We couldn’t do better. We’re that much safer here. If she has no idea of who we really are, and anything happens, she’ll act totally innocent.”

Gerd and Inge, for their part, had no idea that Lilly had known what was going on for a long time, for, as was her habit, she had betrayed nothing. But she never found out about the things they hid in her apartment.

Nor did Gerd have any inkling of the household’s romantic entanglements. The first night he spent on the couch he heard sounds coming from one of the rooms, which even he, in his innocence, could hardly misinterpret.

“Man, what was that?” he asked Ernst the next day. “Frau Wust’s husband must have shown up last night.”

Ernst stared at him in disbelief and shook with laughter. “How old are you anyway? Don’t you know that our charming Fice has crossed over, and turned our good Lilly’s head hopelessly?”

It had occurred to Gerd Ehrlich that Fice reacted with indifference to the charm he exerted so successfully over the other young women he knew, and for that reason he had dropped his usual flirtatious banter with her. Nevertheless, this explanation appeared highly unlikely to him. Not with a woman with four children, and the Führer hanging on the wall, he pondered, until finally he arrived at an explanation that suited his world view: Men were a scarce commodity in wartime, and this was probably a makeshift solution. He himself had masturbated with a friend as a young boy, and was a long way from being homosexual.

The far-reaching changes in her life were almost too much for Lilly, who had suffered from a weak heart condition since birth and was still recuperating from her jaw operation. But she was the kind of person who pursued with enthusiasm anything she undertook, and so she added another item to her list: She wanted to divorce her husband as quickly as possible.

Felice became greatly upset on hearing this news, and ran to Inge to discuss it.

“She’s meshuggah! Think of what would happen if my name came up in court!”

“You must be out of your mind,” Inge said to Lilly, trying to discourage her from her plan, “thinking of getting divorced with four children!”

“Don’t you think you owe your children a stable home?” her parents-in-law commented in their Prussian mode, feeling vindicated in having instinctively rejected this redhead as a daughter-in-law.

“For God’s sake, child,” Lilly’s mother pleaded, clapping her hands over her head, “have you gone mad? You’re totally vulnerable! Who will take care of you in your old age?”

“First four children, and now divorce! Couldn’t you have thought about this sooner?” Father Kappler growled in exasperation.

“Don’t worry, I won’t be coming to you for money,” Lilly countered harshly.

Günther objected as well, of course, and behaved in the customary fashion of husbands in such a situation. What would he do if he knew the real reason, Lilly mused, and relished the thought. Too bad he could never find out! Günther employed the usual threats to keep the mother of his children tied to him. He wanted the apartment, he told her, and two of the children, and Lilly was to assume entire responsibility for the breakup of the marriage. His extramarital escapades of course carried less weight than hers.

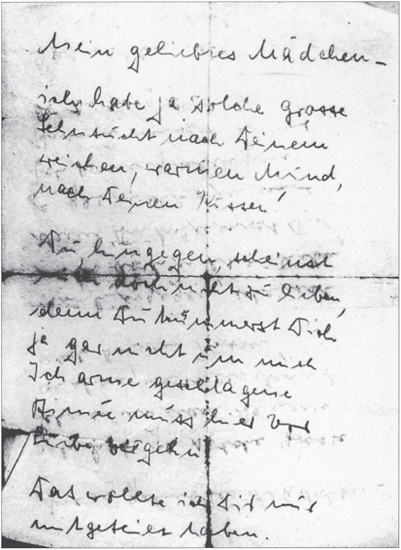

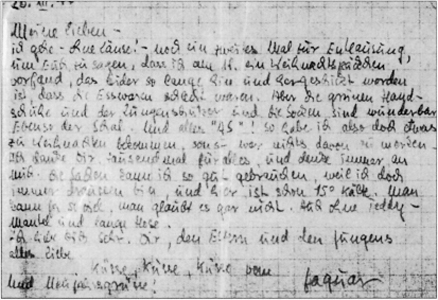

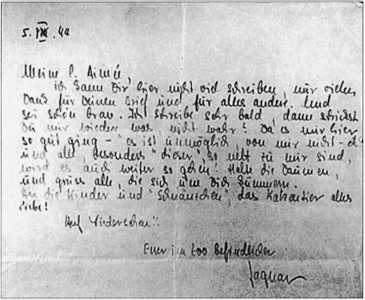

A note from Aimée to Jaguar.

Felice in 1941 on the Selbachs’ balcony at Bornstrasse 4 in Berlin-Stieglitz. The Gestapo was in possession of this photograph when Felice was picked up on August 21, 1944.

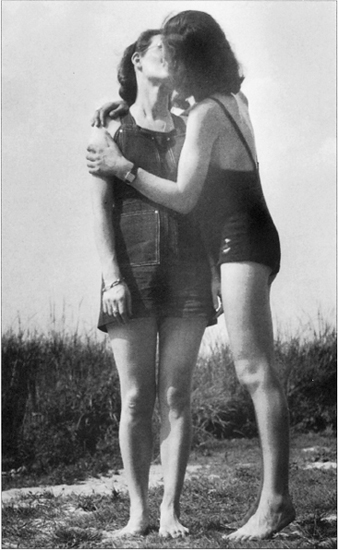

Lilly shortly after their “wedding night,” in Grunewald, April 1943. It is the first photo Felice took of her.

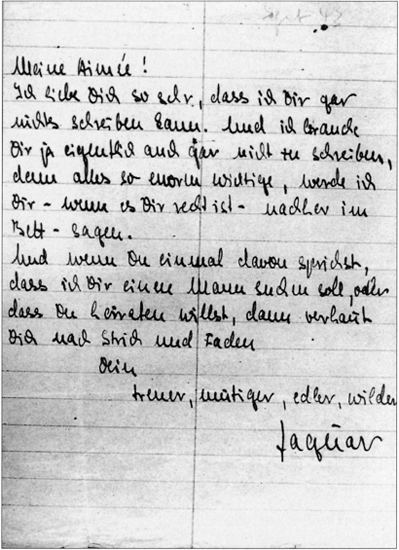

Dated September 1942, a letter from Jaguar to Aimée.

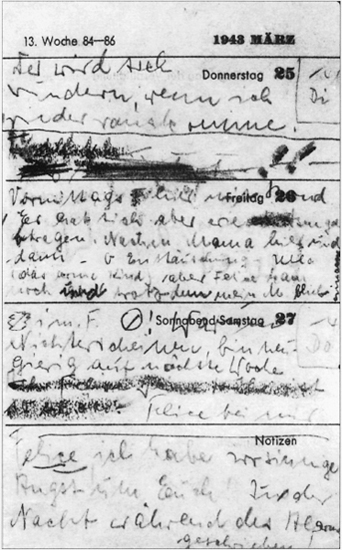

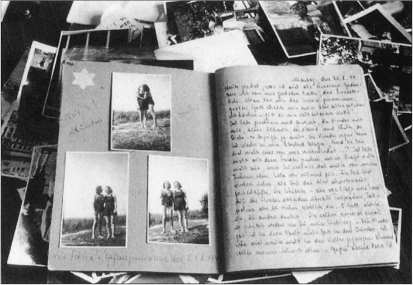

A page from Lilly’s calendar during the time she was in the hospital. March 25, 1943, was their “engagement day.”

Taken earlier on the day of Felice’s arrest by the Gestapo, August 21, 1944, at the Havel River. Taken with a self-timer and developed after the war.

A letter from Felice written in the “Jewish collection camp” at Schulstrasse 78 in Berlin.

Lilly’s “book of tears”: a copy of a page from Lilly’s diary, and all the letters and poems that Aimée and Jaguar wrote to each other, copied by Lilly in the winter of 1945.

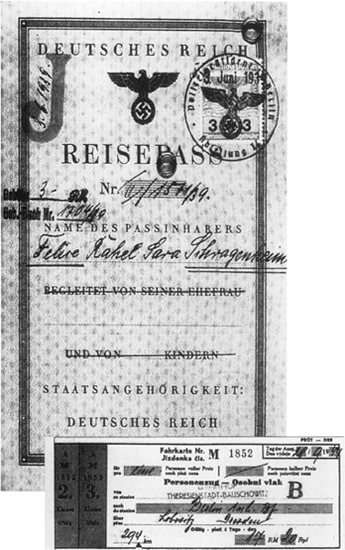

Top: Felice’s passport. Bottom: Lilly’s train ticket to Theresienstadt.

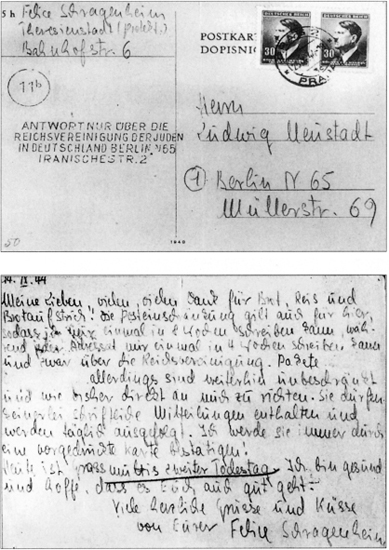

A postcard from Felice, written at the Theresienstadt concentration camp.

Felice’s last letter from the Gross-Rosen concentration camp, written on December 26, 1944.

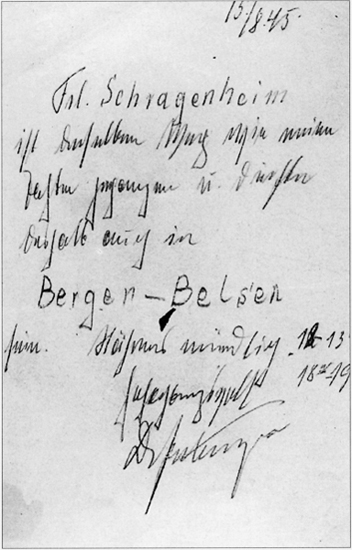

Dr. Grünberger’s letter to Lilly: “Fraulein Schragenheim took the same path as my daughter . . .”

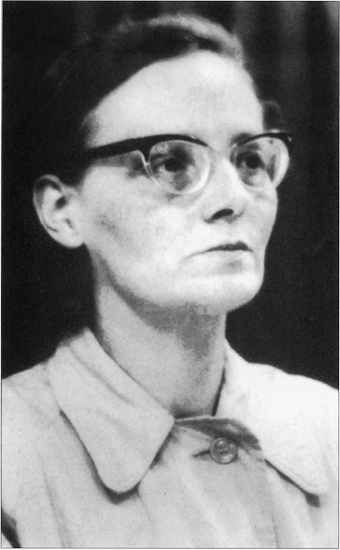

Lilly in the spring of 1947.

Felice in a photo taken by Ilse Ploog in January 1944.

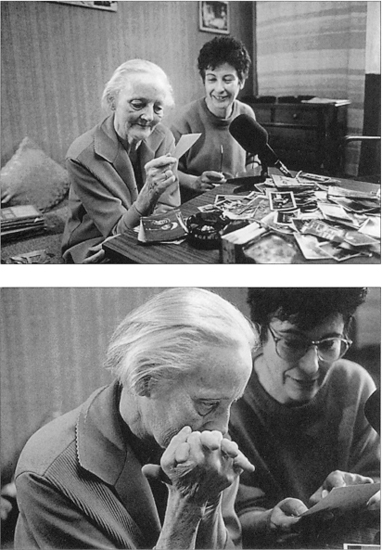

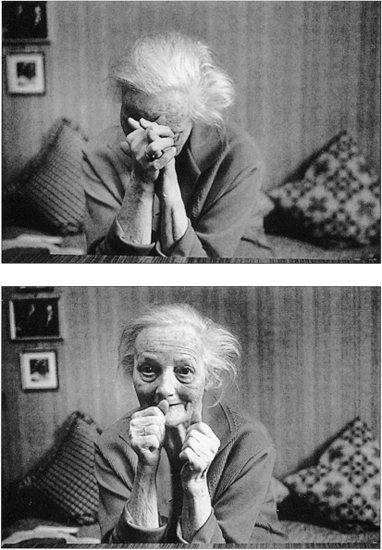

Lilly Wust and the author in February 1991.

Lilly Wust in February 1991.

Lilly Wust in the spring of 1993.

Lilly felt pressured from all sides.

“I have a difficult time ahead of me. You must help me to get through it,” she wrote on the back of a shortening ration voucher issued for children between the ages of six and fourteen. Each time she purchased butter, margarine or cheese, her shop on Breite Strasse stamped “canceled” on a coupon on the pale yellow ration sheet. The constantly tipsy shopkeeper who sold groceries, canned goods, butter, fruit and vegetables was called Adolf Hoch [“Adolf Hurrah”] of all things, a name Felice found hilarious.

Lilly was also beginning to feel pressure from within the household, for gradually Inge was coming to realize that in arranging the encounter at the Café Berlin, she not only had found a splendid home for Felice, she also found herself losing her lover. Felice’s other affairs were insignificant to her, there would always be time for monogamy later, but a Nazi! On top of which, Inge harbored a deep distrust of Lilly. In her opinion Felice had made a big mistake in telling Lilly the truth about herself. But Felice was relieved not to have to hide things from Lilly. And now Inge was reproaching herself for setting up a situation in which Felice was delivered, for better or worse, into the hands of this Nazi woman who was in love with her. Lilly and Inge quarreled more and more often.

I’m terribly depressed again, of course. I truly do not understand Inge. She knows she’s tilting against windmills. If this is her great love—well—I would have felt the same way too, at first, if the tables were turned. But then, precisely because I love you, I would have given you up, even if it had broken my heart. I would much prefer for the other person to be happy. And what good does that attitude do her? What does it change? She can’t seriously ask us not to love each other. Or do you think that would be better? But I’ll tell you one thing outright: I will not consider losing even a small part of you, I will hold on to you as fast as I can! I can do that—and most important of all: I don’t want it any other way!

Lilly was impressed on the one hand by the sexual freedom exhibited by the ménage à trois of Inge, Nora, and Elenai—she preferred not to know what Felice was up to—for after all, Lilly herself had not passed up any opportunity. On the other hand, the girls carried on a bit too much; why were they always quarreling with one another? She once again used a postcard to express her thoughts: “I will tell you where your dissatisfaction lies,” she primly admonished Felice. “All of you take things a bit too far, and in the process you destroy the intimacy that needs to exist between people. You think only of yourselves, all of you, and of whatever suits you.”

Sunday was the one day Lilly and Felice could sleep late. On Sunday there was no Inge arriving at the door at eight in the morning. Lilly looked forward to Sunday all week. The children, too, knew that once their mother had given them their Sunday breakfast, they were to look after themselves all morning, and were more than happy to run around their room and be able to do what they wanted. Each Saturday evening Lilly prepared a second, late-morning Sunday breakfast, for Felice and herself. She then had only to reheat the fried potatoes and pour the barley malt coffee. The morning would pass quickly between dozing, eating, reading, and making love. Their friends knew not to put in an appearance before 4 p.m.

The doorbell rang on one such Sunday in June. Eberhard opened the door to let in Elenai, whom he knew. In higher spirits than she had been in a long time, she stormed into the balcony room where Lilly and Felice were lounging about in bed. On Lilly’s sewing table across the sundrenched room from the balcony lay two yards of gold lace with which Lilly intended to trim one of her dresses. Delighted, Elenai wrapped the glittering lace around her mop of curly black hair and then around the waist of her summer dress. Thus attired she played dancing girl for the couple. Suddenly the large double doors to the study opened and there stood Lilly’s mother, frozen to the spot. Lilly froze in place as well, for neither she nor Felice had anything on under the covers.

The situation could not be hidden after that, and Lilly decided to take her parents into her confidence. Perhaps then they would better understand why she wanted a divorce. Everything spilled out one afternoon when she paid them a visit. Lilly not only informed them that Felice was Jewish, she told them the truth about Felice and herself as well.

“We’re lovers, and want to stay together.”

After a moment of shock that seemed to Lilly to go on forever, her father was the first to regain his composure.

“And what will you do later?”

“Oh, seduce young girls,” Lilly said impudently, to cover her embarrassment.

Lilly:

Actually, my parents weren’t surprised at all. At that moment they probably thought back to my youth, when they had done everything in their power to suppress that. They sent me to dancing lessons and brought young men over to the house. Horrible! I was always being introduced to some suitor or other. It was dreadful!

When I was seventeen my father wrote a poem: “Every crush on some young man begins with a girlfriend and from afar/and Lilly too, was carried away by a teacher on the horizontal bar.” In my seventh year of secondary school I got a terrible crush on my gym teacher. She was small and wiry, and had black curly hair and dark, sparkling eyes. In a word, I found her wonderful. Out of sheer desire I became the best gymnast in my class. And then I found out where she lived. She had a room in Spandau, and I would lie in wait for her there; sometimes I would almost freeze, I can still remember that. I would just walk back and forth, and once I even dared to show up at her door. I lied the blue right out of the sky, saying I had an aunt who lived in Spandau. She was very embarrassed, of course. She was really in fear for her life, the poor girl. Carola Fuss was her name, and she was Jewish. (Just as Jews showed a liking for me, I showed a liking for them, that’s the way it was.) The others were always making fun of me: Ha, there she is again, they would say, or: Hey, she just went that way. Girls are so spiteful. And then the whole thing came out, someone probably squealed. The faculty was in an uproar about it. They called a meeting at school because of it, which I had to attend with my parents, and they almost expelled me. But then I told them my side of the story, and they realized that I was totally oblivious and innocent. Even then I didn’t know what it was all about. And my parents never discussed it with me, people just didn’t talk about things like that. Everything was so vague: You don’t do that, you don’t feel that, that doesn’t exist. Somehow, in their subconscious, they already knew, yes well, she’s, you know . . .

Today I know why it’s so easy for me to put my arms around women. I do it automatically, I always could. After I graduated, for example, and before I began my compulsory service, I attended a school for housework, in Saarow-Piskow in 1933. By that time I was already engaged to be married, but I had a girlfriend. Everyone was always whispering about us behind our backs because we went around holding hands. We liked each other an awful lot, but neither of us knew what was going on. Our beds were next to each other and we didn’t do anything, but the other girls got all riled up about us. Had we known at the time what was going on, I never in my life would have. . . . And then she got married too. I still have pictures of her daughter; Felice took them. I made an extra trip with Felice to see her, and when we went into the kitchen together she began complaining about her husband. Our friendship waned during the war. If we had stayed together everything would have been different. Her name was Lotti Radecke.

I always said it was a good thing that there was an “e” at the end of her name, because there was a scandal at school once involving me and a girl named Gerda Radek. The teacher who instigated the whole thing was our professor. It all began on a class outing, and Gerda Radek’s mother was there too. We did nothing more than hold hands. I only remember that they said I had acted in an immoral way toward her, and that is absolute nonsense. Her mother said something to the teacher and the teacher called my parents. Something like that couldn’t be allowed, it was outrageous, and so on. My parents were shocked, but they saw that I was totally without a clue. We were forbidden to sit next to each other after that. One of us had always sat behind the other in class, so that we could pass notes. They forbade us to be friends, really, and we obeyed. Gerda withdrew completely. And after that we became somewhat enemies.

I always had girlfriends, bosom buddies, so to speak. For years I had a friend named Lotti Thiede. Her parents were always giving house parties, and I could stay overnight because it would get too late to go home. One time three of us were sleeping in two beds pushed together. I was in the middle and suddenly Lotti moved over closer to me. And I said to her, quite gruffly, “What do you want from me?” I was terribly sorry for that later. She had one leg that was shorter than the other, and was a very dear person. That was terrible of me, I’ll never forget it. I didn’t understand anything then.

So finally, when I started up with boys, my parents heaved a sigh of relief: Thank God, she has boyfriends!

The fact that Felice was Jewish was frightening enough to Lilly’s anxious mother, but her parents were much more concerned about the other thing. At the same time they could not help but notice how happy their daughter was, and how Felice was spoiling her. Father Kappler would happily have given his Nazi son-in-law the boot were there no children involved. Yet despite their misgivings they accepted Felice into the family with astonishing magnanimity.

Felice took Papa to her heart the first time she met him, which was at Christmas. As he stood before her, tall and thin in his nickel frame glasses, she turned pale and had to sit down: The resemblance to her own deceased father was amazing.

Lilly was preparing for a long life together with Felice, and bravely battled the fear of an unknown future. War, four children, no experience other than cooking, changing diapers, and cleaning, and with a Jew hiding in the house—what she had taken on was no small thing.

Felice, please don’t make the mistake my husband made. If for some reason I get irritated or furious, don’t add to it by arguing with me. Just say nothing, and be very good to me later. It’s not that I’m insensitive, but just let me rage, it will pass just as quickly if you do. When will we ever be able to be alone (Inge!)? I think it will only get worse in the future (our dear friends!). Let’s hope for the best. After all, there are two sides to everything. Who knows how much time we’ll have to be alone together!

Say, I just had a great idea! How about a marriage contract? For my part, for example, I could pledge to be faithful and lovingly patient with all your manifold responsibilities . . .

At the moment I’m so eternally—it’s not that I’m despondent or disheartened, just eternally sad. Never make me any promises you can’t keep, never! I truly believe you will never leave me, a woman like me doesn’t get left. The best thing would be for us to really be in the world, to build a whole new future. But thinking this, I feel sorry that you’re so young and burdened with such an old woman as I. But you will be, won’t you? And gladly? For me!

Do you know what? I want something of yours, so that I will truly know you belong to me. We can’t wear rings, unfortunately. I don’t know what it will be, but there must be something. Felice, my girl, I am thinking about your eyes. Felice, I love you, the more so the longer we’re together. I’ll make a list of the things I wish to keep. It will be nice at our place, you can depend on that. Will you be able to get me a couch, too?

I get a little worried when I think about my future. But it’s not that I’m afraid. I’ve thought carefully about what I want to do. Carefully! I want to live with you—and be happy. To pull myself out of my routine—I don’t belong there. I would rather experience great unhappiness and be destroyed by it than live in moderate happiness to a moderate end. Felice, I have never loved anyone with so little consideration of everyone and everything else. Don’t leave me alone!

By June 1943 only two Jewish institutions remained in Berlin: the Jewish Hospital and the Weissensee Cemetery. Over six thousand Jews still lived in the city, in mixed marriages and in the underground. On June 10 the total assets of the Nazi-instituted “Reich Agency of Jews in Germany” were seized—a total of eight million Reichsmarks. Dr. Walter Lustig, director of the Jewish Hospital, was entrusted with the founding and management of the “New Reich Agency,” to be housed in the administration building of the Jewish Hospital. The agency was barely given the opportunity to do anything for its compulsory members. Under the eyes of the Gestapo, its few Jewish employees, partners of mixed marriages, administered to the city’s last Jews, until April of 1945. The ill were treated, those underground were hunted, widowed partners of “mixed marriages” were picked up and deported, burials were performed and statistics kept.

Lilly and Günther Wust were bickering constantly. He absolutely refused to give her a divorce, though he had been living with his girlfriend, Liesl, for a long time by then. Surprisingly, Liesl came to Lilly’s aid by putting pressure on Günther to marry her. Lilly and Günther finally thrashed out a compromise on the children: Günther would take the two oldest boys, Bernd and Eberhard, and Lilly would keep Reinhard and Albrecht. Lilly’s female friends were horrified that she had agreed to this with such relative nonchalance, but Lilly was almost certain that, due to his situation, Günther would not hold up his end of the bargain. Once Günther finally agreed to a separation, the next stage was the battle over money and who would get to keep what from their apartment.

I’m going to see my husband again. But I’ve decided that this will be our last conversation. I don’t want to do this anymore. He’ll just have to figure things out somehow. I’m finished with it, and won’t discuss it with anyone except you and Inge. He imagines everything will be so easy: He’s in for a surprise. At any rate, things aren’t going to happen as quickly as he would like. By the way, about your typewriter? It would be very nice if I could have it. I’d like to get something accomplished finally. I’m so afraid of everything, but I’m always like that. And then once I get into it I feel better immediately. I absolutely want to make it on my own, to stand on my own two feet.

And you will help me, won’t you? You do love me! And I really will have only you—nor do I wish it any other way. Forget about everyone else: I love you more than my life! I so want for everything to turn out all right—and then—then the world will be ours. (But I won’t take care of your suits!!!)

“And I don’t like your circle of friends, by the way,” Günther said, as if in passing, during one their arguments.

Lilly stared at him in disbelief, and her expression hardened. Did he realize that he had found the key to keeping her under control? Feeling stung, words he once had spoken suddenly pushed their way forth from her memory: “Save me the child, at least.” She had almost died giving birth to Reinhard. “Save me the child, at least.” Anyone who could utter a sentence like that was capable of anything.

From then on Lilly agreed to everything Günther asked.

And as if she didn’t have enough problems with Günther, Inge was adding to her anxiety. “Please don’t leave me alone tomorrow night,” Lilly pleaded with Felice, after Inge told her that Elenai suddenly had announced a visit.

“What is love, torturous happiness, glorious pain?” she noted at the end of June on the back of four expired pink food coupons:

God knows, everything from before is extinguished for me, Felice. It simply no longer exists—everything is today, everything is tomorrow, it shines no matter what. I love you so immensely. And you love me! My girl, my beloved, beautiful girl. I don’t think we could get along without each other. Without each other it just doesn’t work. And that’s how it should be from now on. A lifetime long. There is nothing I wish more fervently than that. One should never say never, and never say forever, but I want to say it and have it be true: We shall remain together forever, never leave one another unless it were for the best. I don’t see why two women cannot make their way alone together, completely happy and in harmony with one another. What do we need men for! I’m not at all afraid. After all, you’re “man enough” for me, isn’t that so? You know that you must always protect me, and also that you want to. I know from experience that one doesn’t need a man in order to be happy; in the end they simply are different creatures, living on another star and seldom letting us poor women in. I have experienced this not once, but many times. And you, my dearest, you are something unutterably familiar to me, you are really I myself! We are truly a wonderful idea. My life up until now was not lacking in love, God knows, but was empty of life, real life. I have spent years living for nothing, have wasted my life. And that is not what life is for. I want to live, to love with all the fire in my heart, to savor life and love to the fullest. I will never stand before you empty-handed. I will look after you, be your homeland, your home and family. I will give you everything you lack, and I know that my call in life is to make you happy—my Felice.

As of the end of 1942 Felice and her sister Irene had succeeded in finding a way to correspond with one another, through an Emmi-Luise Kummer in Geneva, Switzerland. Frau Kummer had been the governess of Alix Rosenthal, one of Irene’s school-friends, back in Berlin. Frau Kummer would copy sections of their letters to each other and forward them to London or to Berlin. It sometimes took a letter from London fourteen days or even a month to pass both the English and the Wehrmacht High Command censors, and to arrive in Geneva bearing its blue mark. Many letters never arrived at all. On July 6 Irene thanked Felice, whom she called Putz, for a photo she had sent. “I really can merely clap my hands above my head,” she wrote, “and say girl, girl, how you have changed. But that’s because I keep thinking: Putz is seventeen and not twenty-one.”

Felice began calling Lilly “Aimée” at the first sign of their fondness for one another. Aimée, or Good Common Sense, was a play by Heinz Coubier, and actress Olga Chekhova had presented a copy of it to Felice in January 1940, “in memory of a play that gave so many people and me joy.” It was a simple comedy, set in the period following the French Revolution, and it premiered on April 30, 1938, at the Schauspielhaus in Bremen. The character Aimée is introduced as a young woman “whose irrationality hides a good deal of intelligence.” Lilly liked the name Aimée—Beloved—yes, that was what she wanted to be, beyond measure, forever. And didn’t the description of the character fit her as well? Everyone told her she was irrational, but wasn’t it a sign of intelligence to abandon the suffocating narrowness of her previous life and throw herself into adventure before it was too late? Was there anything more unreasonable than to grow old, like her mother, at the side of a man she did not love?

On June 26, 1943, Aimée used Felice’s green ink to record her part of a “marriage contract”:

I will love you beyond measure,

Be true to you unconditionally,

attend to order and cleanliness,

work hard for you and the children and myself,

be frugal, when it is called for,

generous in all things,

trust you!

What is mine shall be yours;

I will always be there for you.

Elisabeth Wust, née Kappler

“And you?” she wrote on the back side of the postcard. On June 29, using a double sheet of real stationery, Felice answered the challenge:

In the name of all responsible gods, saints and mascots I pledge to obey the following ten points and hope that all responsible gods, saints and mascots will be merciful and help me to keep my word:

1. I will always love you.

2. I will never leave you.

3. I will do everything to make you happy.

4. I will take care of you and the children, as far as circumstances allow.

5. I will not object to you taking care of me.

6. I will no longer look at pretty girls, or at least only to ascertain that you are prettier.

7. I will not come home late very often.

8. I will try to grind my teeth quietly at night.

9. I will always love you.

10. I will always love you.

Until further notice,

Felice

“It is strange,” Lilly wrote during a train ride once, “that when I think of the future, I never think of the children, it is always as if we will be alone together.”

Bernd Wust:

Mutti fed and diapered us, of course, but she did not enjoy being a housewife, for sure. She was always carrying on about how, when the war was over, we would all be able to eat out of cans, thank God, and she wouldn’t have to clean any more vegetables. I always experienced the opposite: When we were invited to Grandma’s, I noticed that Grandma had a completely different attitude toward the household and cooking and so on. She cooked like they do in the Rhineland. I didn’t like the way things tasted, but because Grandpa wanted me to I had to compliment the food. Sweet and sour veal fricassee, for instance—maybe that wasn’t a Rhineland recipe at all—but Grandma was the only one who cooked it. Grandpa was a very funny man, but he became an absolute and obstinate grouch later. That’s how he was all the time, it was his way of getting through life. Not exactly courageous and brave, but he knew how to hide that behind a lot of nonsense. But he was an excellent grandfather to us children. He could get all four of us on his bicycle. There was a wide pedestrian promenade with benches in the middle of Hohenzollerndamm, and he would take us there, small as we were, and joke that we should watch out for the policeman.

One morning Inge appeared ready for work to find Lilly and Felice still in bed in their darkened room.

“Inge, open the window, please,” Felice purred lazily, as she wound a strand of Lilly’s tousled hair around her finger.

“I’m not your servant,” Inge growled, and with a furious, “This is really too much!” slammed the bedroom door behind her and went to work in the apartment. There followed a loud and furious battle of words between Lilly and Inge, and Inge’s career as a domestic was over. Her bag was waiting for her at the door.

But her departure was not unanticipated. Some time before, Inge’s boss at Collignon had told her that he wanted her back at the bookshop. In the end they went together to the Labor Office, and he succeeded in getting Inge released from her job by proving that she was indispensable at the shop. On June 21, 1943, Inge finally returned to being a bookseller, relieved to have escaped the tension at Friedrichshaller Strasse. For Felice and Lilly, this marked the beginning of a period of freedom.

My Felice-girl,

I’m sitting on the train to Grünau. Can you tell that I’m thinking of you? Whenever my heart moves or aches for some reason, I believe you are thinking of me! Why does love hurt so? As a result of a few love affairs I once had, I thought perhaps I didn’t truly know how to love. Now I know that I can. I love you. You really are my “first person”! Before, I would sometimes get the strangest feeling of guilt, that something wasn’t right. I was ashamed—and now—now my feelings spill over without end.

On July 13, 1943, the Central Office of the Gestapo in Berlin sent a letter to the presiding president of the Berlin-Brandenburg Revenue Office, Department of Property Holdings. The letter requested the confiscation of the assets of “the Jewess” Felice Sara Schragenheim, stating that as of June 15, 1943, she had been registered as a fugitive. The request was quickly filled. On July 1, 1943, the correspondence section of the Prussian State Bank of Berlin reported to the president of the Revenue Office that assets belonging to “Felicie Sara Schragenheim,” account number J 361 224, had been seized following an announcement appearing in issue number 144 of the Deutsche Reichsanzeiger of June 24, 1943.

Sometime between July 14 and July 26, 1943, Felice sent a letter via Emmi-Luise Kummer to Irene in London. Irene passed it on to Felice’s friend Hilli Frenkel in New York:

Of course I think your Fritz is delightful, since he likes you and because that makes you happy. Hopefully I’ll get to meet him soon. Give Ludwig my regards a thousand times; sometimes I feel longing, but I think it would be good if it stayed at that, without the necessary disappointment that would come if we saw each other again. Or doesn’t he think so? I really know nothing whatsoever anymore about slim, dark-haired young men. And at seventeen I had thought I knew so much about them! Wherever love falls—that’s what we used to say, and would you find it very bad if my love fell elsewhere? You don’t understand entirely, do you? Doesn’t matter, we’ll talk about it sometime. . . . Lilly is entirely delightful; you must meet her. Not an outstanding personality, not at all intellectual, just average intelligence, she makes an endearing effort to get involved in my world, my books, my interests, and to live with me the way I want to. Of course I thus have a lot of responsibility, but I gladly take it on, considering that I have someone who unconditionally belongs to me and sticks by me. Living together is simply wonderful. Each of us makes such an effort to offer the other a hundred little joys and to be considerate. Sometimes we don’t say a word to each other an entire evening, but we know that the other one is there, and that’s a lovely feeling. Our primary principle is not to get on each other’s nerves and not to bore each other. I’m mostly in charge of the latter, since I constantly keep her in suspense, as she always assures me. The children are delightful and very well-bred, especially the little ones, “ours,” who we will keep after the divorce. They are two and four years old, simply darlings. Just now the divorced spouse has arrived—Lilly has gone to visit someone. He’s a nice guy, but the two of them just don’t get along. He gets along fine with me.

Somewhat later: It was really delightful. Five minutes after her husband arrived, her charming father came. I have to call him “Papa” and he just loves to kiss young girls. The third one who showed up was Gregor, a writer, for whom I occasionally type. He is often at our place or goes out to eat with us. He is in his mid-forties and aside from having a wife and child he also has total understanding for Lilly and me. He is six-and-a-half-feet tall and everyone calls him “Good Gregor.”

And I am the housewife caught between these three worlds. Everyone complimented me afterwards for how well I managed to avoid any pitfalls.

I’m still at Mutti’s. But of course she notices that I’m not particularly enjoying it. Talk it over, argue, make up—that’s how it always goes. Yet she still has a strange power over me. If only I didn’t have the feeling that she takes ample advantage of that. Next week she’ll be going to the “Forst” and I’ll probably drive up on the weekend. Unfortunately Lilly can’t find out—it’s difficult with women.

Under the Damocles’ sword of Günther’s threats, Lilly agreed to assume partial responsibility for the failure of their marriage. This meant that she was eligible for only one year of alimony payments. In July, in preparation for her life as a divorcée, Lilly enrolled at the Rackow Language School on Wittenbergplatz, signing up for a course for beginning interpreters of English, but she first had to learn German shorthand and how to type. When her morning class ended, Felice would be standing at the school gate in her white linen shorts. Side by side they would then bicycle through Wilmersdorf, to sit chatting for a while on a bench in Hindenburg Park before it was time to go home to the children.

The population of Berlin still believed that the city’s air defense would be able to ward off any major attack on the Reich capital. They had become accustomed to the minor destruction caused by “mosquito attacks,” and listened with sympathy, though somewhat incredulously, as refugees from the Ruhr District talked about whole streets on fire and cities that had been totally destroyed. But Berliners’ composure gave way to growing anguish when in nearby Hamburg, between July 24 and 30, roughly fifty thousand people were killed by British fire bombs and high explosives as part of “Operation Gomorrah.” On August 1 a handbill was distributed to all Berlin households ordering all women and children, and the sick and elderly, to leave the capital. With the temperature hovering around ninety-five degrees, masses of the population stormed the train stations and ticket agencies. Thousands left the city to camp at night in the surrounding forests. Thousands more went to visit friends and relatives in the country, taking their possessions with them for safekeeping. The Völkischer Beobachter quoted Frederick the Great: “In times of storm and distress, one must have insides of iron and a heart of brass in order to rid oneself of all emotions.”

Newspapers reported that “well-prepared” Germans would “defy the terror of the bombing.” Valuables should be taken to friends in less-endangered areas for safekeeping. Pieces of paper bearing the exact name and address of the owner were to be attached to furniture, rugs and household possessions. “Once and for all, women and children belong in the cellar,” warned the Hakenkreuzbanner (Swastika Banner), the National Socialist newspaper of Mannheim and North Baden that soon was to play a part in Felice’s life story. As there was a danger with high explosives of being buried in the debris or of burning to death, Berliners were instructed to memorize the escape route they would take out of their air raid shelters. It was forbidden to obstruct shelters with crates, equipment or air raid shelter bags. Openings in walls had to be blocked off, otherwise they might function as a chimney in the case of fire and imperil an otherwise secure building. People were to take with them to the cellar only what was necessary for the most basic survival. “A few hand towels are more important than silverware, rugs, paintings, or a hundred volumes of classical literature,” according to the Hakenkreuzbanner. Above all, candles, matches, gas masks, blankets and water were needed. If cellar exits were buried in rubble, and burning embers on the basement ceiling raised temperatures to a dangerous degree, shelter inhabitants could survive by soaking blankets and coats with water. They were then to dash through the burning building with their mouths and noses covered with the damp cloth. Each resident was to keep an air raid shelter bag packed with savings book, food coupons, drinking water, and “provisions” ready-at-hand. Clothing worn in the shelter was to contain as little rayon and cotton as possible, as these materials were flammable. Heavy leather gloves and coats and vests of leather were preferable, as well as glasses that offered protection to the sides of the face, like skiers’ or welders’ glasses. Women could tie a scarf around their heads.

“Do men belong in the air raid shelters?” the newspaper asked rhetorically, to answer: “Their responsibility is not to protect themselves, but to protect the community from harm.” Fire was best fought with sand and water; stick type incendiary bombs looked like white fireworks, phosphorous bombs spit and smoked, sparks could be put out with firebeaters but phosphorous fires could not be, as the firebeaters would cause sparks to fly in all directions.

The city was greatly uneasy; each evening Berliners waited for the major air offensive to commence that was constantly being announced by the BBC. Each night city-dwellers vanished into their cellars at the first sound of the sirens. People stormed the train stations; anyone who didn’t have to remain in the city headed east or south. The pavement was stripped from the city’s squares and every patch of green was dug up to make way for air raid shelters. Any male pedestrian who happened to be strolling by was stopped by the block supervisor and put to work with a shovel. Maintaining a rapid pace was advisable. Not until August 27, after Berliners had regained confidence in their air defense system, did the long-awaited event occur. In the event of a bomb attack, “U-boats” like Gerd Ehrlich had to hurry to reach the public shelters in time.

Gerd Ehrlich:

The Berlin radio broadcast went off the air at 9 p.m., which was customary when enemy planes were approaching. I hurriedly put on boots and jacket and strapped on my Hitler Youth belt. I waited at the door, my briefcase packed, and then the sirens went off. So I left the house quickly and walked along the street for a bit. For the last few times I had gone to a wonderfully large cellar in a building on Bismarck-strasse. A former classmate of mine lived there, Klaus H., a half-Aryan who, as such, was left more or less alone in an acceptable job. That day I barely reached the building before the flak let loose and began firing. The lights went out and dust floated down from the ceiling. The cellar swayed like a ship at sea; women began to scream and it seemed as if the whole building was going to collapse. After a few minutes of confusion we began to collect ourselves. The air raid warden ordered all young men to the doors. Klaus and I were elected to check the property. So we put on our steel helmets and set off. We had a stunning view from the roof. For one moment we forgot the danger we were in. The night sky was blood-red as far as you could see, and above us things that looked like multicolored Christmas trees were being fired on by German antiaircraft planes using tracer ammunition. Searchlights singled out individual planes, but they were undaunted by the furious attack and kept flying, to fearlessly swoop down on some industrial or rail target and thus escape the line of fire. Then we hurried out onto the street. A strong wind had blown up, sending smoke, ashes and leaflets all over the place. We quickly gathered up several copies of the “Appeal to the German People” that the planes had scattered, and stuck them in our pockets. The attack had lasted only an hour perhaps, but the damage was rather considerable. Two days later I walked through streets that still were on fire. That night I had to wander around until about 3 a.m., as my building was too stirred up for anyone to enter unnoticed. I helped put out fires in various buildings and carry out furniture.

Felice, known and loved by the neighbors as Lilly’s charming friend, accompanied Lilly and Bernd to the cellar at the sound of the sirens, while the three youngest children spent the night in the children’s bunker nearby, a privilege not all mothers enjoyed. At first Lilly had delivered them to Herta, the shelter attendant, personally, but later they walked over on their own. The boys thought themselves very grown-up when, at a quarter to six, they held hands and crossed Kolberger Platz to Reichenhaller Strasse. Eberhard, thoughtful and considerate, was responsible for seeing that “Chubby” was handed over to Sister Herta’s care. Albrecht, not yet two years old and still in diapers, was too young for the bunker, actually, but Sister Herta had taken a fancy to him and turned a blind eye to his presence. As the other children climbed into their bunk beds with their teddy bears, “Chubby” was allowed to snuggle up against Herta’s ample bosom. “Fold your hands/bow your head/Think of Adolf Hitler only./He gives us our daily bread/And leads us out of worry” the children would murmur in chorus, their eyes on the picture of the Führer. Then lights-out was called and those on the lower bunks would begin kicking those above them in the small of their backs. “Quiet!” Sister Herta roared, pressing “Chubby” to her and thinking wistfully of her Hans, from whom she had heard nothing for more than two months, since the capitulation of German and Italian troops in Tunisia.

At home, a stressful time began for Lilly with the wailing of the sirens.

“Come on, hurry up!” she would moan, running nervously back and forth with her air defense bag between the front door and the bathroom. But Felice would stand at the mirror, combing and combing her straight and brittle dark brown hair. It would have been unsightly were it not for the fact that her hairdresser kept it elegantly waved. It required constant care and had to be in perfect order before she would proceed to the cellar. The more presentable Felice was to the other residents the safer she felt.

After the all-clear siren, the tables were turned.

“Don’t fall asleep, please don’t fall asleep,” Felice would plead, as Lilly sank down on the stairs in exhaustion and had to be dragged back up to the apartment. With Lilly stretched out motionless across the bed Felice then had to undress her, not infrequently leading to Lilly’s suddenly being very wide awake. When the children returned the next day, ringing the bell at 8 a.m., they both were dead tired.

It was around this time that Ernst, Jolle and Gerd asked Felice if she wished to attempt an escape with them. Lutz, wanted for arrest following his heroic forging of identification papers created from supplies stolen from the German Red Cross, had succeeded at the end of May in fleeing to Switzerland—with the help of a female “escape helper” and an ID from the Reich Armaments Ministry, permitting the bearer to travel in the vicinity of the border.

Felice and Lilly despondently debated the issue: to flee or to stay? And—unnoticed by Lilly—Felice, Inge, and Elenai were also holding vehement debates. An unlawful escape across the border to Switzerland was by all means dangerous. And there were more than a few incidents of Swiss border guards sending fleeing Jews right back across the border into Nazi Germany.

Lilly weighed leaving the children behind and following Felice into exile. There were a number of children’s homes in southern Germany; after the war they could come for them again. Lilly was sure there would be an “after.” Felice, for her part, was skeptical. The rumors she had heard and quickly suppressed were too horrible for her to be able to imagine an “after.” But she did entertain the idea. As it was a well-known fact that escape-helpers were not interested in money but in things, Felice wrote to Luise Selbach in the Altvater (Jeseník) Mountains and asked her to return her possessions. Mutti, to whom Felice’s relationship with Lilly was an unforgivable breach of loyalty, had crated Felice’s things—carpet runners, linens from several apartments and, above all, her grandmother’s expensive Persian lamb coat—and shipped them to the “Forst” and to Olga in Eastern Pomerania for safekeeping. She was irritated by Felice’s request, and always came up with new excuses. She had always admonished Felice that someone “on the run” could not stay in any one place for long. Lilly dutifully tried to talk Felice into leaving without her.

An unsigned letter from August 1943 was found describing the weeks of torment. It was written in green ink and the handwriting could easily have been Felice’s.

My Dear Beloved,

I cannot imagine life without you. Does such a thing exist? Doesn’t one change, doesn’t one become a stranger to oneself during every moment of separation, and discover oneself anew at each reunion? Am I to do without you for days, weeks, months, do without your voice and hands and mouth? Do without the certainty that all of your thoughts are with me, and mine with you? Must I give up everything I love? Am I never to be permitted to be unconditionally happy? Distance, time, custom—must we be threatened as well by these mortal enemies of love? Or is our love so weak that longing, that slowly fading fire, will only do it good? Why am I writing all of this—I love you so much, in a way I have never felt, never known before. Now I am tormenting you and me. Why does one torment that which one loves? Because one loves.

Elenai was amazed when one such letter written by Lilly came into her hands.

“Tell me, why are you always imitating Felice’s handwriting?”

“That’s love,” Lilly answered.

Elenai, Inge and Felice decided that, in view of the uncertainty of escape, Felice was safer remaining in Berlin. Felice knew that this was her last chance to leave Germany, and drew nearer to Lilly.

NIGHTS

I love to bend above you there,

To gaze into your sleeping face.

Your gentle breath disturbs the air,

And fills the twilight’s still, gray space.

When my eyes across your clear

And oh so familiar features glide,

I comprehend at once, my dear,

The wonderful gentleness you provide.

As with some masterwork of art,

I sink into you like a stone,

Respond to the silent call of your heart,

But suddenly I feel alone!

You are so distant, and stricken with fright,

I suddenly know just where you are.

I lift you up. You sit upright

Return to my world from afar.

My Aimée!

I love you so much that I can’t even put anything down on paper to you. But it’s not really necessary to write you at all, for I can tell you all of the enormously important things I have to say later—if it’s all right with you—in bed.

And should you even once mention that I should help you find a husband, or that you wish to marry, then you are off-base—right, left and center.

Your loyal, brave, noble, wild

Jaguar

It was the first time that Felice called herself Jaguar.

On August 10, 1943, Felice wrote to her sister Irene in London:

What does Fritz look like? When I read the name I always think of my Fritz, the best friend I had, and then I get very, very sad. And still it is possible to forget everything and to assert that I am completely happy. How long that will last—I fear, based on my experience, that it won’t last, but that might be because today, after an absolutely wonderful Sunday at home, we got some bad news. At the moment I am sitting in almost pristine white shorts with an almost perfect crease (due to Lilly’s devoted ironing services) on our balcony, from where I can look out over the allotment gardens, and she is sitting across from me, pensively filing her nails. I really have to describe to you sometime how she looks, so you’ll recognize her if it gets to that point. Now she has switched to crossword puzzles, and occasionally demands erudite words from me. So: Charlotte-Elisabeth, 29 years old (but the cigarettes that she is thus authorized to obtain are all smoked by me), with a figure like the one I had at seventeen. Consequently, she wears all my summer dresses that don’t fit me anymore, with my broad shoulders and otherwise rather athletic figure. She is a bit shorter than me and anyway looks like she’s eighteen, so that no one believes she has four children, or a husband, since she doesn’t wear a wedding ring. Due to her French family background, according to my friend Gregor, she has prominent Celtic cheekbones in a narrow face, a very high, rounded forehead, a narrow, delicate mouth and dark brown eyes, which are very unusual with her copper-red hair. She is in part—with good reason—proud of her hair, but in part she also has a complex because of it, just like with the rimless glasses that she has to wear, and with which I think she is prettier than without—and that is what matters! Michael Arlen wrote a novel Lilly-Christine—and that’s her! My small watch from Käte looks outstanding on her narrow hands. It is virtually reprehensible how much fun I have making her blush and when she squints a little then I am ready to give her all my assets without a thought. No, I should find another comparison, since they are a thing of the past. When she turns red she also reproachfully calls out my name, which she never shortens on principle. These are all superficial things, you’ll find them overstated and maybe hard to believe coming from me. But those are the facts! If I didn’t have her—well, you could not even imagine. But you must, and you must promise me that you’ll make good for it all someday if I cannot. She’s getting divorced, now I’m responsible for her. You shouldn’t consider that impetuous; I am fully aware of my accepting it all, since it is nothing compared to what she is always prepared to do. This is not meant to be a “last will and testament,” but you have to understand that I want to know that I have taken care of it. My things, the linens and silverware that I have, are mostly stored at Mutti’s so that I can’t get to them now. As far as possible, Lilly should have that; at least it is something. You cannot imagine how hard it is for bachelors to get all their things back that have been left in their various more or less furnished abodes. People who are otherwise decent then have either a very short memory all of sudden or else they just misplaced the key to the basement.

Mutti is at the “Forst.” Considering I got her a fantastic seat on the train and up to now have been cooking and vacuuming every other day for her husband and oldest daughter, she hasn’t even written to me at all or passed on her regards to me. I don’t know what’s the matter with her. She’s also miffed that I want my things back. And that I don’t really want to keep playing the cleaning lady for nothing. By the way, that doesn’t keep her from asking her daughter if I took care of this or that, or got something for her. I don’t understand it at all, and I’m not doing anything for her. That she made great demands on me, without standing by me in the least when I loved her so much, doesn’t really entitle her to utterly exploit me now that that is long past and I have another person who stands by me. Maybe that sounds ungrateful now, but even when it was wonderful to adore Mutti, I was always aware that it was an illusion that cost me a lot of time, money, and headaches. . . .

Lilly has meanwhile finished the puzzle to our general satisfaction. She even found a city in Arabia, which I really marveled at. But if it was the very last word to be filled in then it wasn’t all that hard anyway. It’s getting to be bedtime; just a little more of Dostoyevsky’s Crime and Punishment and then to sleep. . . . Tomorrow Lilly will start learning office skills at a commercial school. Recently we have often ridden out to the old canoe stomping ground to swim, but generally we enjoy ourselves the best at home. I also have a lot of retouching to do. Now and then a movie—that’s all.

On the second day of each month Aimée and Jaguar celebrated the second of April, the day that Felice first crawled into bed with Lilly. On September 2, 1943, Jaguar and Aimée exchanged rings. Aimée’s was a gold wedding ring with “F.S.” and the date “2.4.43” engraved on the inside. She gave Jaguar her silver ring with the green stone. Felice’s hand was so small that she was only able to wear it on her right middle finger.

My Most Beloved Girl!

On our wedding day—a long and yet thrilling half-year—I wish you, and myself as well, the very best. Above all—a happy future! And along with that, a little money, a nice apartment, and nice friends. The latter we shall certainly never lack, and we’ll have the apartment as well. But money? Well, we’ll see! What can happen to us, right? With our love! And what more do we want!

I love you without end and will never leave you.

Your Aimée

At the end of September Felice had an appointment to meet Ernst Schwerin and Gerd Ehrlich at a café on Savignyplatz.

Gerd Ehrlich:

We had planned to meet the girl there at three-thirty, but we arrived somewhat early. Ernst sat down at a table and I, dressed in my uniform, went to the buffet to pick out a few pieces of pastry for us. There were several people in line in front of me, and directly before me stood a member of the secret service. I hadn’t been standing there for five minutes, the secret service agent had just been served, when suddenly I felt a hand on my shoulder. Turning, I recognized a Jewish colleague from E & G, who had gone underground with her parents, but who had been picked up by the Gestapo a short time later. We knew that since her arrest this girl—her name was Stella Goldschlag, and her beautiful blond hair had earned her the nickname “the Jewish Lorelei”—had been working for the police as an informer. She had managed to turn over a number of Jews to the officials.

“Hello, Gerd, how are you?”

“I’m sorry, Fräulein, I don’t know you. You must be confusing me with someone else!”

“But no, you’re Gerd Ehrlich, don’t you remember me, we worked together at Erich & Getz!”

“You’re surely mistaken, that’s not my name!”

At this moment the official in front of me picked up his order and turned around. He probably was working together with the informer; she would finger illegal Jews and he would then arrest them. If I were taken to a police station my lovely identification papers would do me little good at all; I couldn’t let it come to that. I gave the girl, her hand still stretching out for me, a shove on the chest. Then I whistled to Ernst to alert him to the danger, and at this moment the secret service man reached out to grab me. Ernst, who saw that I was in danger, jumped him from the side and the tall guy fell across the buffet table. All of this happened within the space of a few seconds. Before anyone had the chance to recover from their surprise, we were on the street. We raced around the corner and up the streetcar platform, down the other side, and then jumped on a passing streetcar. When we reached the Bahnhof Zoo station two stops farther on and were sure we weren’t being followed, we got off and took the streetcar one stop back to Savignyplatz. We had to get back to the café in time to warn Felice before she fell into the trap. We kept an eye on the café entrance from the corridor of a building across the street. Finally our friend arrived. We were able to get her attention before she went in, and took her to another restaurant, where we told her what had happened.

For the first time I had experienced something that made me truly nervous. Even more disquieting was the news we received from a comrade who worked for the Gestapo. Stella had given them my name and description, and now I was on a list of wanted persons, complete with picture. It was time for me to fold up my tent in Berlin.

Two weeks later everything had been prepared. The escape helper wanted a bicycle and a typewriter, perhaps some money, and these had to be found somewhere. Hedwig Meyer, who lived in a villa in Grunewald and dressed only in black after she lost two sons on the eastern front, took care of everything else. She sent an encoded telegram to farmers in Singen, Baden, who would take care of preparations for the refugees’ escape into Switzerland and show them a safe border crossing. At ten on the evening of October 7, 1943, their friends gave Gerd, Ernst, and Ernst’s fiancée, known only as “Chubby,” a small farewell party in celebration of their “vacation.” Earlier that evening Gerd had picked up Inge from Collignon’s to take her to dinner with what remained of his food vouchers.

Once on the train the three travelers passed two ID checks by the Gestapo without incident. After spending the night in a Stuttgart hotel, they took a local train to Tutlingen, and after a brief stay there went on to Sigmaringen. After a stop midday the three then took the next local to Radolfszell on Lake Constance, and there changed to a train that took them to the border town of Singen, where they arrived as scheduled at 5 p.m. They had been warned to avoid the closely guarded express train that ran from Stuttgart to Singen in favor of the branch line. The “lady in black with bicycle” was waiting for them at the station, and they had been instructed to follow her as inconspicuously as possible. Their adventure ended in the Swiss village of Ramsen, after a night spent in woods where they almost took a wrong turn and headed back into what would have been sure death. A young Swiss border guard picked them up on a country lane and took them to his customs house. The Berliners couldn’t understand the Swiss German of the Berne sergeant on duty.

“Parlez-vous français?”

Sergeant Fisch wanted to send them back to Germany posthaste.

“Do you have a gun?” Gerd asked.

“Yes.”

“Can you shoot it?”

“Yes.”

“Then shoot. That’s the only way you’ll get me to go back.”

Gerd Ehrlich then asked to be permitted to call Washington.