SHADOWS ON THE WALL, PROTO CINEMA AND THE CINEMA OF ATTRACTIONS1

The crystal ball was the first vision machine.

Kenneth Anger, 2006

The great work of light is the shadow.

Athanasius Kircher, 1604

It is only necessary to live half a century to become aware of the rise and fall of hemlines and the eternal re-cycling of human ideas and passions. This is not to suggest that time stands still within tight circles of recurrence, and there is no denying the breathtaking technological advances of the last decades. However, a brief journey through the history of film reveals many elements that might well have been cast off in the digital age but instead prevailed and resurfaced, refreshed in the work of contemporary artists, especially when taking the form of moving image installation. We will selectively revisit film’s labyrinthine history, one that is marked by the intermittent presence of artists whose own evolution coils around that of the mainstream in a cultural double helix.

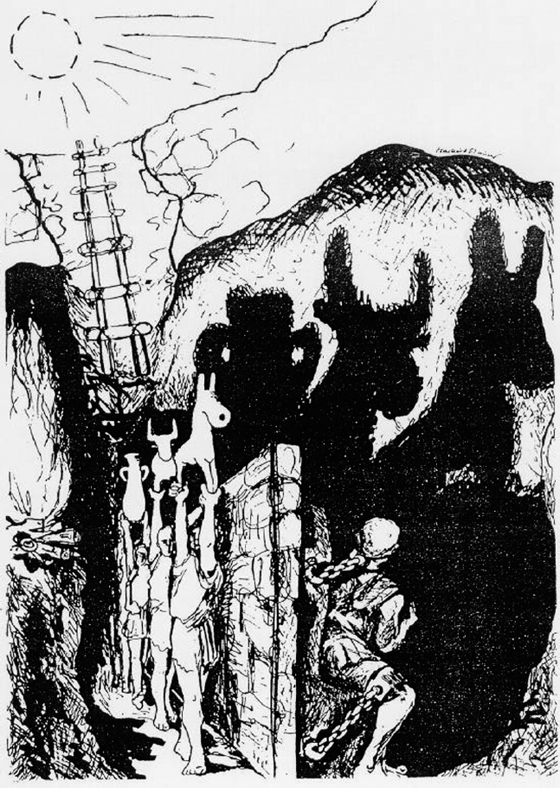

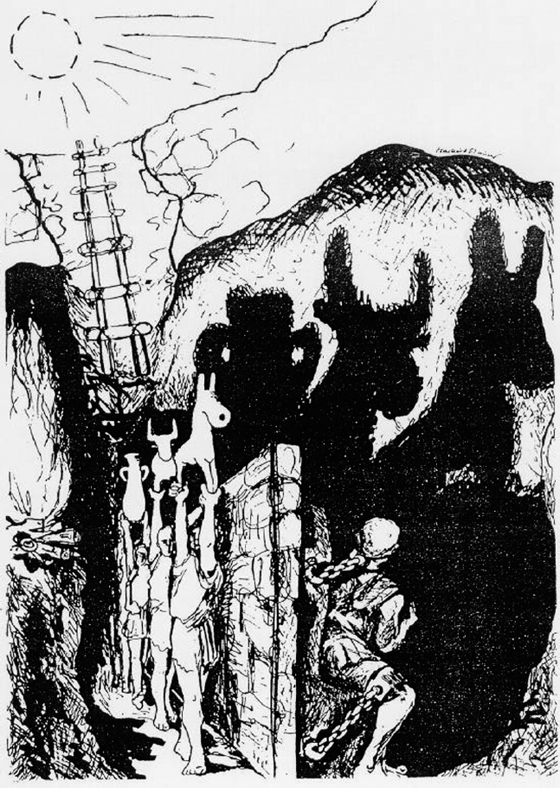

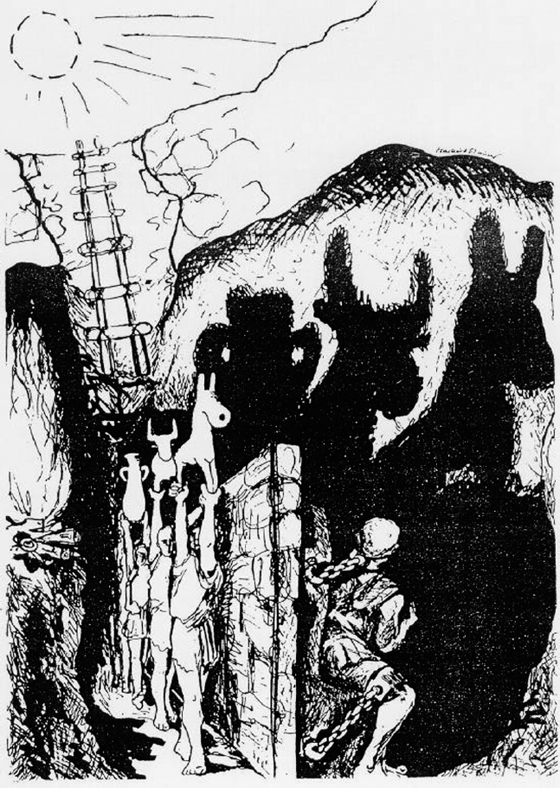

We might begin our journey with Plato’s cave, arguably an early instance of film but also, and perhaps more plausibly, the first moving image installation albeit in the form of an apologue (moral fable). In his Allegory of the Cave, from Book VII of The Republic (circa 380 BC), Plato imagines a conversation between the great philosopher Socrates and his pupil Glaucon. Socrates describes a dark cave in which manacled prisoners, cut off from the world outside, are turned to face a bare wall. A fire burns above the entrance to the cave and a walkway allows humanity and its artefacts to pass through casting a procession of shadows onto the wall the prisoners are condemned forever to contemplate. Being indexical images, the shadows move in synchrony with the sounds made by the flow of individuals thus heightening the impression that the shadows are alive. Socrates asks Glaucon to imagine that the prisoners are then led out of the cave and exposed to the bright light of day. The bedazzled men would not recognise reality because ‘to them … the truth would be literally nothing but the shadows of the images’ and for a time, the hapless prisoners would only perceive the shadows of men and trees as real’.2 Plato’s story is a parable of a journey away from the world of knowledge based on the senses into the light of higher intellectual enlightenment and goodness. Sean Cubitt nominates Plato’s story as ‘a precursor of every theory of cinema and video as false consciousness’,3 while Duncan White specifies Jean Baudrillard’s notion of the simulacrum as a direct descendent of the shadowy cave, one in which ‘the copy becomes more real than its original and images show us only themselves and not the world around us’.4 Where Jean-Louis Baudry highlighted the structural homology between Plato’s cave and cinema ‘in which the camera, the darkened chamber, is enclosed in another darkened chamber, the projection hall’,5 the allegory also evokes the power of filmic representation and the progressive displacement of reality by the world of idealised cinematic illusions in the twentieth century and beyond, a theme that underpins much of the discussion of moving image installation throughout this book.

The world of illusions began deep in human history with shadow plays and puppetry, and knowledge of optics produced the camera obscura, a device that had been in circulation since the time of the ancient Chinese. The camera obscura was refined in the era of Aristotle, nearly four hundred years before Christ and in the first century AD, by the Islamic inventor Alhazen. The imaging device changed little over time: a box or darkened chamber gave up an image of life outside by concentrating light through a small aperture, later focused in a lens, and directing it to an opposing surface. Initially, the image came out upside down and it was not until the eighteenth century that a mirror was used to invert the image into a more conventional orientation. By now, Plato’s shadows were endowed with light and colour, and created an instantaneous image of reality that served both as an aid to painters in the early and high Renaissance and as a source of fascination and delight for avid enthusiasts of optical curiosities.6

The period of the Enlightenment in the eighteenth century saw the scientific achievements of man challenge the primacy of a Christian God and the study of optics was instrumental in shifting the emphasis away from the ‘delusions’ of faith to the illumination of empirical evidence. Citing Charles Musser, Lucy Reynolds has argued that in spite of Enlightenment rationalism, and the association of the photographic image with scientific discovery, it never lost its connection with darkness, with shadow and the human capacity for depravity.7 Tom Gunning concurs, noting that early optical devices enabled a narcotic fascination with the grotesque. Such unearthly curiosities were associated more with the Augustinian ‘lust of the eyes’ than the contemplation of transcendent beauty.8 In the early twentieth century, Jean Epstein developed his theory of photogénie in relation to film, which he described as ‘any aspect of things, beings, or souls whose moral character is enhanced by filmic reproduction’.9 Rachel Moore has expanded the notion to expresse an ‘urge towards contact with the radically other’.10 This referred not only to the strangeness of the remote Breton Islands Epstein captured in his films but also to cinema itself, ‘for it is cinema that is alien and magical’.11

Gill Eatherley, Aperture Sweep (1973), performed at Filmaktion, The Tanks, Tate Modern in 2012. Courtesy of the artist. Photograph © Tate.

In the Middle Ages, the camera obscura and magic lanterns were associated with the practices of dark magic and the occult world of demons and ghosts. Ironically, it was a seventeenth-century monk, Athanasius Kircher, who is credited with inventing the first magic lantern. Kircher discovered that a candle contained in a box, its light condensed and directed through a lens and from there projected through a painted glass plate, could produce looming images on a facing surface. By raising spectres mechanically, he hoped to disprove the early Christian belief in spirits. As Reynolds explains, ‘a shadow is an indexical imprint of a living presence’12 or indeed a paper cut out, and not, as Kircher wished to demonstrate, the work of the supernatural. In 1992, Gary Hill rekindled the early association of photographic imaging with phantasmagoria in his interactive video installation Tall Ships. Ghostly, attenuated figures were summoned from the darkness by ambulating spectators breaking infra-red beams guarding a series of screens. Perhaps like Kircher’s demonstrations, Hill’s sepulchral simulations of the spirit world did as much to promote a belief in the existence of the supernatural, what Reynolds calls a ‘status of otherness’13 as it did to disprove it.

The science of optics has successfully re-animated the hallucinatory world of the paranormal, both at the dawn of cinema and in the analogue phase of film and video.14 Early black and white video in particular, with its ectoplasmic forms bleeding into the surrounding darkness had the unique ability to conjure the ghost in the machine, not least in Hill’s early works, in which supine, monochrome bodies palely inhabited a row of funereal monitors. Reynolds has identified a similar ‘spectral return’ in the work of artist-filmmakers of the 1960s and 1970s such as Malcolm Le Grice, Guy Sherwin and Gill Eatherley. Reynolds applies this theory to Eatherley’s Aperture Sweep (1973) a work in which the artist, standing between the projector and the screen, uses the shadow she casts to transform her outward appearance, a power Reynolds argues is ‘associated with the occult and magic ceremonies’ and, one could add, the fearful powers of witchcraft. We see in these works an enduring fascination with the moving image and its ability to transport the viewer into another reality or, as Robert Smithson put it, the ‘power to take perception elsewhere’.15 That other realm is often haunted by the image of the artist herself, already and always a revenant, a shadow of a long-lost presence looping indefinitely into the future.16

MAGIC SHOWS

Beginning with magic lanterns and early cameras, and eventually evolving into the movie cameras that came of age in the nineteenth century, photographic devices gradually perfected the art of raising ghosts, at the same time revealing the wonders of the natural world and the man-made achievements of modernity. The evolution of optics also gave rise to a technological showmanship that specialised in fooling the eyes of a citizenry already susceptible to the enchantments of scientific demonstrations and the magic tricks of prestidigitators. A brief detour into this colourful history will identify aesthetic and structural concerns that recur in moving image installations in the twentieth century and beyond.

With the development of photography in the 1830s, the images first projected by Kircher became more life-like and lanternists soon discovered that it was possible to create simple movements by activating several lanterns or projectors in quick succession, thus achieving spatial and temporal transformations. With the impression of movement now added to their repertoire of amazements, legions of itinerant showmen, often carrying their equipments on their backs, took their magic lantern shows to castles and inns across Europe and North America. A contemporary description of a performance of Etienne Robertson’s Phantasmagorie in the 1790s reads like an expanded cinema event from the 1970s, but rather more dramatic:

Suddenly the lamp went out. Thunder roared and lightning flashed. Church bells tolled, the lightning and thunder increased, and a tiny figure – half- human, half-demon – appeared in the air, shimmering and ghostly. Gradually the figure seemed to approach, growing larger and larger, until suddenly it disappeared with a wail. Bats fluttered on the walls, ghosts and goblins groaned, skeletons came hurtling toward the audience.17

This alarming spectacle was achieved with the help of several assistants manipulating projectors mounted on mobile platforms, some pointing at screens and walls, and others, anticipating Tony Oursler by several centuries, projecting into billowing smoke. In The Influence Machine (2000), staged in Soho Square in London, Oursler used dry ice rather than smoke and the images he directed at the wafting clouds were video sequences featuring the faces and voices of inventors associated with the development of what he called ‘disembodied communication’ including Etienne Robertson himself and John Logie Baird, the inventor of television. The ghostly echoes of these pioneers of illusionism wafted through the square and dematerialised as the ‘smoke’ dispersed.18

The nineteenth and early twentieth centuries saw the evolution of ever more elaborate proto-cinematic devices including ingenious fairground attractions such as the pleorama, in which audiences sat in a life-sized, pitching ship while a giant, illuminated screen painted with ships and maritime events scrolled by. The viewer enjoyed the illusion of sailing while remaining stationary. Mechanically operated waves roiled the hull of the vessel as the audience journeyed from coastal France to Byzantium. Not only did this gadget anticipate flight simulators of the twentieth century, but it also prefigured the travelogue format that became a staple of both mainstream and experimental moving image.

One of the most famous of these early travel simulators featured in a scene from the film Letter from an Unknown Woman (Max Ophüls, 1948). The seduction of Joan Fontaine by Louis Jourdan takes place in a motionless fairground railway carriage in which a series of countries appear to glide past the window. The scrolled travelogue is operated by a fixed bicycle, hence its name: cyclorama, a device that in its successive exposure of images passing through a fixed frame anticipated the technological revolution that similarly progressed static images through an aperture, but this time fast enough to create the illusion of movement. In 1980, Bill Brand turned back the film history clock when he created the proto-cinematic Masstransiscope in Myrtle Avenue, a disused subway station in Brooklyn. Brand installed a frieze of hand-painted abstract images equivalent to single film frames, partially hidden behind a slotted housing. The sequential images could be viewed only from a passing train, which provided the momentum to animate them into a motion picture show, winding down into separate, static frames as the train came into the next station, simultaneously unravelling the magic of film.19 Where the pictures moved and the viewer remained stationary in the cyclorama, the reverse was true some ninety years later in Band’s ingenious Masstransiscope, a work that paid homage to the great pre-cinematic inventors of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries.

Bill Brand, Masstransiscope (1980). The installation consists of two sections separated by a staircase. The artist is seen at the entrance to the long section of the work as the train passes by. Photo: Martha Cooper. Courtesy of the artist.

Magic lantern shows often involved narrators, musicians and early foley artists adding sound effects. Audiences could be given instruments to play on cue and were encouraged to applaud and/or jeer and generally interact with the scene unfolding around them. These audio-visual spectacles became extremely elaborate and as the art of lantern shows evolved, they were fast approaching the condition of cinema. In the 1870s, the great American lanternist Joseph Beale deployed projected images to create three-dimensional narratives. Terry Borton describes the scene:

…sequences of slides not only track the action, but move the ‘camera angle’ or point of view, shifting perspective to emphasize psychological points. Dissolving images, close-ups, fades, cross-editing of story-lines, etc. are all part of Beale’s artistic repertoire for telling stories on screen.20

These live-edited extravaganzas anticipated not only the role of post-production editing in film, but also the psychedelic light shows of the 1960s, adapted and elaborated by American artists such as Stan VanDerBeek, Jack Smith and Lewis Klahr. We may also identify Beale as a precursor to the 1970s expanded cinematic works of the British artist Nicky Hamlyn that involved the live manipulation of projectors as well as more recent work by the Americans Gibson and Recoder. Perhaps the most striking parallel with Beale’s live projection events is the film Projection Instructions (1976) by Morgan Fisher in which written instructions appear on the screen: ‘turn the volume up/down; centre frame; throw out of focus’ etc., while the projectionist attempts to follow the onscreen directives.

I will return to these works in the following chapters and meanwhile end this expedition into the history of pre-cinematic inventions with my favourite engineer of light from the pioneering days of the nineteenth century. In 1823, Sir Goldsworthy Guerney burned calcium oxide in a hydrogen flame and thereby invented limelight, a form of illumination that came to be widely used in theatres and music halls to irradiate the spectacle on stage. Guerney refined his invention by introducing oxygen into an oil-fired flame, allowing more carbon to be burned, and reducing the likelihood of explosion. Guerney’s ‘Bude Light’ provided the lighting for the Houses of Parliament until the introduction of electricity, but he also used it to illuminate his modest ‘castle’, built on a sandbank in the Cornish seaside town of Bude. By means of a complex arrangement of mirrors and lenses, he was able to light the whole edifice creating an ethereal inner glow like a Tardis about to take off into the cinematic future. In the summer of 1829, he also contrived to project the Bude Light from his castle into his cousin’s room at the Falcon Hotel some four hundred yards away on the other side of the canal. Over a hundred years later, the British collective Housewatch (active in the 1970s and 1980s) similarly transformed buildings into lanterns by back-projecting film and later video onto their windows at night.21 Like Guerney, Housewatch contrived to render solid matter magical and seemingly weightless, closer to a container of dreams than the reality of bricks and mortar. This ability to both affirm and dematerialise walls and ceilings remains one of the defining characteristics of moving image installations.

VISION MACHINES

It was in the early 1830s that vision machines were first manufactured with a capacity for exploiting the persistence of vision or short-range apparent motion, a perceptual phenomenon that takes place when eye and brain are exposed to a succession of temporally-linked images, separated by short episodes of black. At anything over sixteen images per second, we perceive smooth movement as Bill Brand’s Masstransiscope so elegantly demonstrates.22

The zoetrope, otherwise known as the ‘Wheel of Life’ or ‘Wheel of the Devil’, was one of the earliest vision machines, invented in 1834. It was a device that enabled several viewers simultaneously to look through slots in the side of a revolving drum on the inside surface of which was pasted a strip of drawings representing successive stages of movement that come alive when the drum is spinning. Any number of vision machines appeared including Reynaud’s Praxinoscope and Daguerre’s large-scale dioramas while flip books and other optical toys created similar impressions of movement and are still produced for the amusement of children today.23 Tom Gunning suggested that this genre of ‘cinema of attractions’ was temporarily displaced by conventional, single-screen narrative cinema and only re-emerged in later avant-garde practices in the early 1900s.24 As we shall see, the liveness of pre-cinematic vision machines, the dramatic staging of the apparatus and its capabilities, resurfaced in experimental film and video in the 1960s, and a fascination with imaging gadgetry persists into the digital age. As A. L. Rees pointed out ‘cinema films are still viewed as panoramas in dark spaces’, something that is also true of much installation art.25 The panorama itself recurs in the history of artists’ moving image with notable regularity, for example in the circular screens featured in Steve Farrer’s ghostly films (The Machine, 1978) or the panoramic screen presentation mode adopted for the celebration of the work of filmmaker Jeff Keen (1923–2012) in the Tanks at Tate Modern (September 2012). These installations in-the-round create a viewer experience that is both gratifying and frustrating. The spectator can walk freely inside the circular screen and enjoy a sense of immersion in the image but at the same time, there is always the niggling feeling that there is something more interesting going on behind one’s back, signalled by an image dancing tantalisingly on the periphery of vision. The viewer must calculate the relative benefits of staying with the image in the current field of vision versus turning around to explore the unknown in a game of physical channel hopping. It soon becomes clear that inside a panoramic screen, the whole work can never be grasped, often resulting in a futile spinning motion, an observation I will expand on in due course. Perhaps the most accomplished and witty re-creation of a zoetrope is Mat Collishaw’s Garden of Unearthly Delights (2009) in which a cast of impudent putti do violence to nature on a spinning turntable, animated by means of strobe lighting.26 The manic repetitiveness of the naked babies’ assaults on the flora and fauna of Collishaw’s tropical paradise exactly reproduces the short looped actions that are characteristic of a zoetrope while simultaneously creating a parable of the relentlessness of human destructiveness.

Collishaw’s spinning garden was well-received by a general audience and in this respect the work aspires to the popular appeal of the earliest manifestations of the projected image. Our inventive nineteenth-century ancestors created beguiling spectacles of light and shade; they shared the sleight of hand and the showmanship of the fairgrounds, circuses and music halls from which they emerged; they boasted links to scientific discovery in the machine age and transmitted a sense of wonder at the alchemy of photographic illusionism with is darker, mystical connotations, its connection to both life and death. These attributes of the moving image were established in the pioneering days of pre-cinematic lantern shows, dioramas, zoetropes and optical toys and, as I have suggested, found a durable legacy in the work of moving image installation artists throughout the twentieth century and into the contemporary era. Their ludic properties, in particular, will reappear consistently in artists’ work throughout this narrative.

Mat Collishaw, Garden of Unearthly Delights (2009). Steel, aluminium, plaster, resin, LED lights, motor. Image courtesy of the artist and Blain/Southern. Photographer: Christian Glaeser, 2009. © the artist.

EARLY CINEMA

Nature caught in the act.

Spectator of an early cinématographe screening, Paris.

In her looped film performance Reel Time (1971–73), Annabel Nicolson made an oblique reference to another technological precursor to film when she fed a filmstrip through a sewing machine. The film, depicting a shadow play of the artist working at the same machine, then travelled on to a projector that made visible the perforations resulting from the sewing machine’s repeated assaults on the film. The piercings gradually destroyed both the material of the filmstrip and the images of Nicolson it carried. The film performance was in part a reminder of the working conditions of women in textile factories during the industrial revolution and the under-recognition of women’s labour in the home. However, Nicolson was also signalling a link between the mechanical claw action of a sewing machine that regulates the passage of cloth (or in Nicolson’s case, celluloid) past the needle by means of grasping and shifting the fabric along, and an idea that W. K. L. Dickson came up with in 1891 when he was working with Thomas Edison. Inspired by the transport mechanism of the sewing machine, Dickson fed a series of photographic images through a viewing machine, the Kinetograph, by means of locking into a series of sprocket holes running along the strip of images. This created the template for all subsequent celluloid film technology and dominated film production and exhibition until the advent of analogue video and subsequent digital imaging into which the earlier technologies were eventually subsumed.

Annabel Nicolson, Reel Time (1973). Photo: Ian Kerr. Courtesy of the artist.

The short films that Dickson and Edison produced of vaudeville acts and athletes flexing their muscles were shown in ‘Kinetoscope Parlours’ in New York, for a nickel a throw.27 By the 1890s, short films by Alice Guy Blaché, the Lumière Brothers and Georges Méliès in France as well as Jenkins &Armat in America and Birt Acres in the UK also showed in cafés, entertainment parlours, music halls, fairgrounds, scientific institutes and other public spaces, establishing film as a popular form of diversion from the outset, in line with the earlier lantern shows and dioramas. Some of the earliest film footage featured single events designed to show off the new technology to its best advantage: workers leaving a factory, a boat bobbing on the waves, a train drawing out of a station – what Tom Gunning described as a ‘cinema of instants’ as opposed to a narrative cinema of ‘developing situations’.28 The impassive contemplation of reality from the perspective of a static camera was gradually abandoned as cameras became mobile and narratives more complex. However, the steady gaze of the locked-off shot found favour once again in the work of artists in film and video who were active in the second half of the twentieth century and who wished to re-assert the subjectivity of the filmmaker. Static, durational sequences can be seen today as a central component of installations by artists such as Gary Hill, Sam Taylor-Wood, Patrick Keiller and Zineb Sedira, whose use of the magic casement of a fixed frame signals their desire for the viewer to adopt the same level of concentrated attention to a scene that the artist devoted to its filming.

The desire to astonish an audience appears to be timeless and in terms of the moving image began at the dawn of film. A contemporary account gives an insight into the impact of apparent motion on a gathering of citizens attending a screening in 1896. The film featured a turbulent seascape in which ‘a number of breaking waves, which may be seen to roll in from the sea, curl over against a jetty and break into clouds of snowy spray that seemed to start from the screen’29 – a trick now perfected by 3D cinema. Tom Gunning recounts a similar but possibly apocryphal story of the consternation that met the first screening in 1895 of the Lumière brothers’ Arrival of a Train at the Station (1895). Legend has it that the illusion of a train hurtling towards them was so convincing that audiences were either rooted to the spot or, traumatised by this apparent danger, they fled. Gunning goes on to argue that film theorists invested in the mythic image of scattering citizens, this ‘primal scene’ of an audience enthralled by the preternatural power of the image, in order to underwrite a concept of spectatorship centred on the passive consumption of the cinematic spectacle – a theory we will encounter in the next chapter. In Gunning’s view, this formulation ‘underestimated the basic intelligence and reality-testing abilities of the average film viewer’.30 Early audiences were by no means duped by cinematic verisimilitude; in fact, proposed Gunning, they were ‘consciously aware of artifice’ and, when abandoning themselves to the screen, ‘it was the incredible nature of the illusion itself that rendered the spectators speechless’.31 A desire to showcase the filmic illusion motivated the Lumière brothers’ habit of projecting the first few frames of a film as a series of stills and then incrementally cranking the projector up to speed, gradually bringing the sequence to life. They also ran the film backwards for additional effect. According to Gunning, in revealing the critical moment in representation when the perceptual shift from still to moving image occurs, the Lumières demonstrated not so much ‘a scientific interest in the reproduction of motion’ but an ‘allegiance to an aesthetic of astonishment’.32 Gunning concludes that far from mistakenly reading the images as reality, contemporary audiences regarded the great new invention of the modern age as only the latest in a long line of technological novelties. However, the shock of the new would not take place if the vision machine failed to produce a plausible facsimile of reality whilst simultaneously maintaining a sense of the trick being played. Based on his readings of contemporary catalogue descriptions of films of the period made available by Charles Musser,33 Mario Slugan argues that ‘the historical spectator was biased to construe the films in narrative rather than spectacular terms’.34 Not only did many of the early films drive the action towards narrative closure, but also, as Musser emphasises, films were often programmed across an evening’s entertainment to create narrative coherence. Slugan points to the preponderance of narrative in other cultural forms of the day – literature, theatre, music hall – slanting the audience’s attention towards a film’s storyline rather than the ‘attractions’ of the technology. Nevertheless, we can accept Gunning’s thesis that the intoxication of early film audiences was achieved at least in part by presenting cinema as a technological spectacle. The excitement aroused by the capabilities of each new vision machine survives even in the parallel and eventually dominant development of Hollywood productions that effaced the technology in the service of narrative.

In spite of the need for strict representational codes in film entertainment, technical advances continued to provide moments of ‘aesthetic astonishment’, beginning with mobile cameras, the introduction in the 1920s of synchronised sound and in the 1910s of colour.35 Television brought its own technological marvels, up to and including high definition live broadcasting and even in the new digital age, elements of techno-showmanship are discernible in mainstream moving image culture reminiscent of those adorning the infancy of film. Video games, interactive movies such as Mike Figgis’s Time Code (2000), the spectacular CGI effects developed by companies like Pixar, the motion capture techniques devised by James Cameron for his live-action/animated fantasy Avatar (2009) and the new wonders of 3D all return dedicated cinephiles to the same condition of perceptual awe. However, it is in the realm of art and underground film that we find the most resonant tributes to the operating structures and aesthetic preoccupations of early cinema. As the story of film unfolds, it is possible to identify points of convergence between incipient modes of film presentation and later expanded cinematic practices in the 1960s as well as contemporary moving image installation – correspondences that revolve around a common emphasis on the staging of the work.

By the 1920s, movies were being screened in opulent surroundings, in the glittering picture palaces of the epoch. The films themselves were bookended by live acts and interrupted by musical interludes and the whole line-up of entertainment was welded by the connective tissue of the flamboyant masters of ceremony, who, as in the earlier magic lantern shows, encouraged audiences to respond spontaneously to the attractions paraded before them. Embedded in a kind of variety theatre, the illusionism of film was mitigated by live events and the distancing effects of noisily present fellow spectators. The integration of moving image with live performance, with material props, variable lighting and audience participation was characteristic of early film presentations and finds echoes in contemporary installation art. In both cases, the staging of the imaging technology is critical to its impact and internal logic, the vision devices as much a part of the show as the impressions of reality they generate. Both manifestations of film induce an oscillation between hallucinogenic immersion in a simulated environment and embodied engagement with concrete reality. The spectatorial encounter with the work as event in early film and the marshalling of mediums of mass entertainment recur in artist’s engagement with the moving image in general, and installation and the moving image in particular.

The performative and reflexive strategies of early cinematographic practitioners thus transmuted into the experimental traditions of the twentieth century avant-garde. Meanwhile, as I have suggested, the burgeoning film industry and, later, television, notwithstanding their commitment to technological innovation, developed a separate cinematic practice in which the apparatus of cinema was pressed into the service of verisimilitude and fictional narrative. The iconoclastic ferment of the 1960s, together with the rejection of realism in the modernist period, gave rise to experimental moving image in which the technical devices of film and video were once again the main protagonists in the cinematic encounter, while their illusionist capabilities were systematically dismantled and reconstituted in what Raymond Bellour called ‘multiple cinemas’.36 However, before shifting onto the terrain of avant-garde filmic practices, I would like to take a brief excursion into mainstream film history, which, for many was the starting point for developing an alternative practice within the realm of art.

THE EVOLUTION OF MAINSTREAM NARRATIVE FILM

Two film pieces of any kind, placed together, inevitably combine into a new concept, a new quality arising out of that juxtaposition.

Although many features of early cinema persist in both, the bifurcation of film into the experimental avant-garde and mainstream narrative cinema intended for mass audiences began in 1910 and was well under way by the early 1920s. Early cinema had to overcome the problem that audiences of the silent screen needed to ‘understand the causal, spatial, and temporal relations’ of a film.38 Without sound, changes of scene or the introduction of new characters could be confusing and a live narrator was often required to explain the plot. Early directors gradually developed a cinematic vocabulary that communicated their stories more effectively and a regime of representation evolved of such familiarity today that we are largely unaware of its operations in the structuring of the filmic experience. These early mainstream devices included filming the action in depth rather than situating it in a flat, theatrical staging. Noël Burch records that Georges Méliès used colour to create depth in otherwise flat images.39 Lighting was now designed to match the time of day suggested by the scenario. Shot/reverse-shots created a ‘spatial integrity’, close-ups of actors allowed for greater understanding of emotion and motivation and, from 1905, intertitles filled in the potential gaps in audiences’ understanding of the scenario.40 Editing provided continuity, ‘unbroken connection’ between shots and visual cues were used to suggest time flowing chronologically across two shots, or time elapsing between them.41 Vitagraph’s The 100-to-One Shot (1906) is regarded as the first example of intercutting or parallel editing, that is, cross-cutting between two simultaneous events. Single-shot short ‘attractions’ were replaced by longer works and D. W. Griffith developed parallel editing uniting three concurrent events in The Lonely Villa (1909). Contiguity editing created the illusion that a character walks into a scene from one direction, follows a logical spatial trajectory and exits the frame. In the next shot, she reappears in a different location, apparently adjacent to the one she has just departed. The 180° rule was developed in which the camera is restricted to an imaginary semi-circle so that the viewer is able to maintain a consistent orientation of the figures in shot. Cameras were positioned to embody the point of view of different characters and directors matched the eyelines of the protagonist to detail cutaways that followed their gaze. Other, now familiar devices condensed time to make characters wake up in the future, or return to the past in flashbacks. Double exposure (said to have been invented by Méliès) introduced surreal, comical or uncanny effects and more mobile cameras hand-held or on tracks, enabled longer sequences to be shot continuously adding to the sense of a lived, on-screen reality. The studios became larger and more elaborate providing a deeper pictorial space and following the introduction of sound, acting became less exaggerated and more naturalistic. The addition of artificial light and painted backdrops increased the control filmmakers could wield over the dream machine, and the manipulation of the medium became less and less perceptible as the verisimilitude of the scene depicted on screen gradually improved until today’s high-definition images and quadraphonic sound offer the viewer immersion in a staggeringly believable parallel universe.42

The rules of engagement developed in mainstream film were set up like ducks at the fairground to be shot down by successive generations of experimental film and videomakers, with the most energetic onslaught being launched in the 1960s and 1970s. This took the form of a two-pronged attack, one coming from artists’ practice and the other discharged as a scholarly critique of spectatorship, beginning with the condemnation of film as a one-way system of communication. As Geoffrey Nowell-Smith argued ‘there is no reciprocity: when you are watching a movie, you aren’t making one … free exchange exists only as a residual but tenacious myth’.43 A concept of spectatorship promulgated in the 1970s by Christian Metz cast the viewer as a helpless dupe, gripped by a narcissistic, hypnagogic condition.44 Mainstream television and cinema were dismissed as the servants of the state exercising a form of social control through mass hallucination, an accusation reminiscent of Marx’s imputation of religion as the opiate of a gullible populace. We will return to this topic in the following chapter.

EUROPEAN ART CINEMA, ABSTRACT FILM AND RUSSIAN MONTAGE

Although avant-garde artists and theorists of the 1960s can pride themselves on masterminding the most vociferous anti-narrative phase in moving image history, throughout the century there were artist-filmmakers who already saw greater possibilities in the new medium of film than the mere dissemination of popular stories. Germaine Dulac, one of the luminaries of French Impressionist cinema insisted that film constitutes an autonomous practice, an ‘original’ art … an art of interior life and of sensation’.45 In the 1920s and 1930s Dulac along with French compatriots Jean Epstein and Jean Renoir, and with equivalents in Russia, Germany and elsewhere in Europe, worked to resurrect the visionary spirit of the pioneers who first developed the art of moving pictures. These early twentieth century filmmakers created what has been variously described as the narrative avant-garde, first avant-garde or art cinema, to distinguish their practice from avant-garde works descending from Cubism and Futurism or even the more experimental fringes of the mainstream. However, as A. L. Rees has argued, there was much traffic between the different tendencies, well into the 1940s and 1950s, and he advises seeing them ‘collectively … as part of a new cinema outside the commercial genres’ dominated by Hollywood.46

In the 1950s, François Truffaut and the periodical Cahiers du cinéma launched the concept of the ‘auteur’, denoting the director whose singular vision is embodied in the film, whose aesthetic sensibility holds the key to the meaning of a work. This is a notion of authorship that chimed with filmmakers emerging directly from a fine art tradition and who, like all artists, saw themselves as individual creative agents, engaged in Dulac’s ‘art of interior life and sensation’. In the 1920s, the chiaroscuro art cinema of German Expressionism explored the darkness of the human soul, echoing the religious superstitions underlying the phantasmagoria of early magic lantern shows. These Gothic sagas mirrored themes of madness, somnambulism, possession and death, culminating in F. W. Murnau’s Nosferatu (1922), a parable of racial and sexual purity contaminated by the predatory ‘other’, a demonic force that came from the East. Concurrently, the filmmakers of Dada and Surrealism mined the complexities of the individual psyche by creating fantastical dreamscapes evoking the repressed desires and drives being uncovered by Freudian psychoanalysts. The filmmakers used incongruous images to short circuit the rational mind and unlock the secrets of the unconscious including the propensity for criminal violence as was inferred in Luis Buñuel and Salvador Dalí’s classic Un Chien Andalou (1928) in which a man appears to slice into a woman’s eye with a cutthroat razor. In the 1940s and 1950s, the artist’s imagination was explored in a lyrical, non-narrative and impressionistic genre of filmmaking manifesting simultaneously in different parts of the world. For instance, Maya Deren working in the USA directed herself in Meshes of the Afternoon (1943), a meditation on a young woman’s reveries characterised by a languid eroticism but overshadowed by intimations of impending doom. A continent away, Margaret Tait, isolated in the Scottish Orkneys, also raised the question of gendered subjectivity, what she called the ‘atmosphere’ of the maker, but by means of a poetic interaction with a situated, indigenous landscape. Both women exercised a profound influence on women film- and videomakers of the 1970s and 1980s, including Sally Potter, Jayne Parker, Sarah Pucill and Nina Danino. These artists subjected their experience to feminist analysis, positioning the individual in a gendered political framework, whilst simultaneously maintaining a lyrical sensibility derived from Deren and Tait.

While film was being elevated to an art form in European cinema, there emerged a simultaneous emphasis on the artisanal, which proved critical for women’s participation in the burgeoning medium. In the 1910s, Germaine Dulac learned the film trade by getting involved in all stages of production and post-production: ‘It is only by developing ideas myself, exploring sensations, manipulating the lights, the apparatus, that by the end of my first film, I understood what was cinema.’47 In the early twentieth century, the profound engagement with the manual, mechanical and (al)chemical processes of filmmaking also provided the impetus for the expanded cinematic practices of the 1960s and 1970s, as we shall see in the following chapters. Many avant-garde artists drew inspiration from the hand-made abstract films of the 1920s that like Dulac’s ‘art of sensation’, sought to stir the emotions in the moment, through pure rhythm, form, colour and visual harmonies, grounded in artisanal, hands-on techniques. Artists such as Mary Ellen Bute, Oskar Fischinger, Walter Ruttman and Len Lye painted successive images onto glass plates and animated them frame by frame. They worked directly onto clear film stock to create pulsating abstractions that impacted directly on the eye and ear, and the inner rhythms of the body. Hans Richter’s Rhythmus 21 (c. 1921), a parade of expanding and receding squares and rectangles on a neutral black background, dispenses entirely with the figure-ground configuration of objective painting and instead conjures the formal experiments of Cubist painting and their elaborations of pictorial space forever flirting with the outer limits of the frame. As Henri Chomette remarked at the time, these geometric compositions create ‘unfamiliar visions inconceivable outside the union of lens and moving film-strip’.48 The bombardment of the senses with non-representational imagery by the abstract filmmakers of the 1920s produced what Anton Ehrenzweig described as a ‘polyphonic’ art, one that gave rise to a ‘diffuse, scattered kind of attention’,49 a constantly shifting point of focus, analogous to the process of scanning the drip paintings of Jackson Pollock. The non-referential film also gestured towards the contemporary interest in synaesthesia among painters such as Wassily Kandinski. This confusion of the senses through abstraction remains a potent thematic in contemporary work by practitioners such as Simon Payne and Steven Ball, themselves the inheritors of the video abstractions of Steina and Woody Vasulka in the 1970s and 1980s as well as the computer-generated organic mutations created by William Latham in the 1990s.50 Abstract film also anticipates the immersive environments later fashioned by moving image installation artists who made it possible to physically enter and navigate vertiginous abstract worlds.

The non-representational terrain of abstraction was widely held to offer a demotic spectatorial arena. Artists were not ‘making … human beings’, as Barbara Hepworth declared, but ‘a place where you can go’.51 By implication, abstraction becomes a place where anyone can go, and as Iwona Blazwick argued, the universal world of ‘squares, circles, triangles and lines’ is intelligible to viewers, ‘regardless of their language, nationality or place in society’.52 Although the political dimensions of abstraction, including the contradictory impulse to both reject the rational world and find new ways of ‘being one with the universe’53 have found their champions throughout the history of film, the more familiar manifestation of political engagement among moving image artists can be traced back to the Constructivists of the 1920s.54 Fired by the rhetoric of the Russian revolution, the Constructivists regarded the filmmaker as a skilled technician, a craftsman or woman working in the service of the people. In the context of Soviet Russia, technical expertise should not serve the vanities of individual ‘creatives’ as it did the ‘auteurs’ of European cinema. Theoretically, the objective was to mobilise those skilled in the plastic arts to educate the masses in the glories of the Soviet political system. This didacticism nonetheless involved considerable talent, personal vision and technical innovation on the part of individuals as the films of Dziga Vertov, Yelizaveta Svilova and Sergei Eisenstein amply demonstrate.

Leftist ideology motivated many of the ‘cultural workers’ among us in the 1960s and 1970s, particularly those engaged in political campaigns. However, the Soviet filmmakers are more important to later installation artists as formal innovators. Montage was a mode of visual assembly that Eisenstein pioneered based on the principle of abrupt juxtaposition of disconnected shots, which he called ‘cells’, held in dynamic tension through editing. From these disparate elements, a new synthesis was created when the ‘emotional shocks’ associated with each image were brought into ‘a proper order with the totality’.55 In Battleship Potemkin (1925), with its famous scene of the massacre on the Odessa Steps, Eisenstein edited together contrasting images of violence alternating long shots and close-ups. Poignant individual portraits of citizens create moments of stillness, no sooner established than shattered by the sudden introduction of dynamic motion – soldiers marching with guns blazing, citizens scattering in panic. The Odessa Steps episode is conjured with the barest of narrative prompts, creating both an ‘intellectual’ cinema drawing on the deductive powers of the viewer and a cinema of powerful emotional affect, the combined impact of which was pressed into the service of Bolshevik propaganda. Montage and discontinuity went on to dominate the formal strategies of experimental film and video in the 1960s and 1970s and can still be witnessed today in the work of artists such as Elizabeth Price whose gallery installations juxtapose archival footage with the persuasive iconography of advertising and computer graphics. In THE WOOLWORTHS CHOIR OF 1970 (2012), Price courts the ‘dramatic, flowing surge’ (her equivalent of Eisenstein’s ‘shocks’) unleashed by jump cuts between, in this case, dissonant images of 1970s television pop shows, reportage of a department store fire and stark, black and white photographs of a cathedral interior.56 Installation art is almost by definition an instance of montage, an interplay of contiguous components contained within an extruded, spatialised totality. Like the individual shots making up Eisenstein’s incendiary films of the Russian revolution or the conflagration in Price’s Choir, each unit of film, each ‘cell’, gains new, compounded significance in relation to the next, meanings that would only remain latent were the sequences to remain independent. However, as I have emphasised, installation frequently shifts the drama of the encounter from contrasting elements within the frame to tensions between the distancing effect of material, architectural reality and the illusory phenomena onscreen. Like the stars of early Hollywood films engaged in simulated lovemaking, visitors to installations always keep one if not two feet on the ground.57

Elizabeth Price, THE WOOLWORTHS CHOIR OF 1979 (2012). HD video installation, 18 min. Installation view, Baltic Centre for Contemporary Art, Gateshead, UK. Courtesy of the artist and MOT International, London & Brussels.

Elizabeth Price, THE WOOLWORTHS CHOIR OF 1979 (video still) (2012). HD video installation, 18 min. Courtesy of the artist and MOT International, London & Brussels.

If installation and the moving image require a named ancestor, we need look no further than the legendary Abel Gance who anticipated multi-screen installations by many decades with his epic Napoleon (1927). The film tells the story of the great Emperor’s rise to power and subsequent military defeat, and when it was first exhibited Napoleon was projected onto three adjacent screens corresponding to the three fixed cameras Gance used to capture panoramic views of the action. In this manner, the epic battles of the Napoleonic wars were brought to life.58 In the 1970s, Chris Welsby also widened the screen by aligning multiple projections to create a single extended image in his Shoreline series. Welsby deployed six projectors depicting the ebb and flow of waves cascading along the length of an English beach. However, the panorama Welsby devised was an illusion. It was created from a single viewpoint taken looking out to sea at different times of day, and the six temporal ‘slots’ were distributed across the projectors and looped continuously. The extended temporal frame became a key constituent of structural film in the late 1960s and early 1970s and can be traced back to Gance’s Napoleon, which was said to have run for six hours. Where Gance’s innovations were designed to create an expansive canvas for the narrative of Napoleon’s extraordinary life, Welsby’s use of similar techniques served a materialist and minimalist aesthetic that dominated experimental film in the 1970s. However, Welsby and his contemporaries have proved no less inventive than Gance in their approaches to solving the problems of securing the desired shot.

The many irresistible tales about Gance include a report of his strapping a camera to a horse and driving it into the sea to discover what one wave looked like to another.59 This recalls a conversation with William Raban in which he confided to me his plans to lash himself and his 16mm Bolex to the prow of a boat in order to capture the perfect wave in a storm force 8, a plan he thankfully abandoned.60 Gance is also said to have tied a camera to the chest of his camera operator, a trick that innumerable avant-garde artists have since elaborated with imaging devices being attached to every conceivable part of the body and its extensions.61 The ultimate camera/body fusion is arguably Mona Hatoum’s Corps Étranger (1994) in which the artist took an endoscopic camera for a forensic journey through the internal passageways of her anatomy.

Where classical Hollywood cinema generally seeks to mask the presence of the camera operator in the service of cinematic realism, experimental filmmakers emphasise the equivalence in the point of view of the camera, filmmaker and spectator at the moment of reception.62 The image is inevitably modulated by the physical attributes of the individual behind the camera: the height of an operator, the stamina and strength of limbs bearing the weight of the technology, the reach of an arm, the length of a stride, the acuity of vision. The inscription of the unseen but inferred camera operator’s bodily dimensionality opens up a space for empathic identification, a theme we will return to in our discussion of spectatorship. This corporeal inter-subjectivity, launched by Gance nearly a century ago, represents a different kind of engagement to the seamless process of identification that conventional cinematic and televisual grammar induces. Morgan Fisher whose works in the 1970s brought to the fore the body and skills of the concealed projectionist, wrote of his films, ‘they return you to the here and now, and in so doing give you back the body that all other films take away from you’.63

THE ARCHITECTURE OF FILM: THE CRITICAL OCCUPATION OF SPACE AND THE SUSPENSION OF DISBELIEF

If the defining feature of installation art is its critical occupation of space, then it is already systemically aligned with the moving image. Since the dawn of film in the nineteenth century, spatiality has been integral to the means of production and exhibition of the moving image, while the pictorial expanses conjured by the filmic image create parallel, albeit illusory territories. When in 1895 the Lumière Brothers first set up a camera outside a factory and filmed, in real time, the workers streaming out at the end of the day, the triadic relationship of camera to subject and subject to the eye and body of the viewer was established. Consumers of mainstream film culture instinctively grasp the spatial determinants laid down by the Lumières and refined through a century of movie entertainment. These spatial cues function correctly, as long as the screen is within a comfortable viewing distance, and while the logic of the simulated space onscreen mirrors human experience of actual space. At the cinema, knowledge of the spatial parameters of film and the apparatus that regulates their smooth execution is incorporated into the unconscious conceptual grid that structures our reading of the work. Viewers are also adept at ignoring the fact that film itself is made up of light rays projected through a chain of stained celluloid frames to form moving pictures, and they similarly disavow film’s new electronic DNA as digital systems of recording and display have displaced analogue technologies. The materiality of any accompanying audio track easily could be proven, as sound waves will obligingly flicker their energy patterns across the screen of an oscilloscope, but the constructed nature of sound on film is also largely discounted, unless it malfunctions. Motion pictures and sound thus trick the ear, the eye and the brain into believing in what is demonstrably not present. The willingness to suspend disbelief enables viewers to ignore the artifice of the film as well as the physical realities of the projector, the beam of light, fellow spectators and the architecture of the auditorium. In this way, it is possible to take delight in reading the flickering shadows on the screen as a temporary reality to be surveyed, unseen, and identify with the commanding position of the camera/projector.

Spectatorial auto-deception is achieved in the charged space of the imagination. As Bill Viola has rightly observed, this is not a straightforward process: ‘the visual is always subservient to the field, the total system of perception/cognition at work … the awareness or sensing of an entire space at once’.64 However, the pleasures of cinematic illusionism override the optical, haptic and proprioceptive sense-data that tell us where we are located in space. Tuning in to the simulated realities of pictorial illusionism takes place in painting, drawing and monitor-based video, however, film, with its epic scale aided by the penetration of quadraphonic sound and the darkened spaces in which it is shown, more effectively entices viewers away from the here and now into what Jean Goudal termed ‘conscious hallucination’.65 In the following chapters, I shall argue that the loss of haptic and spatial awareness in the cinema is never total, that two realities can be held by the viewer simultaneously, and that the objective world can easily be retrieved to escape the power of the illusion should it become too disturbing – staring hard at the exit sign in the cinema always works for me.

CROSS−MIGRATIONS OF FORMS AND SOUNDS

As we have seen, the pioneers of the cinematograph set the spatial parameters of film and induced the suspension of disbelief by reproducing the dynamism and flux of life; the Russians invented montage, and Abel Gance introduced both multi-screen presentations and the heightened subjectivity of the hand-held camera. The 1920s and 1930s generation, notably the French Impressionist filmmakers, are credited with the idea of film as a synthesiser of the arts. Motion pictures, they said, have the capacity to fuse theatre, literature and painting in the all-encompassing embrace of cinema, an interdisciplinary and transmedial approach that has carried over into installation. As Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell point out, although film is a medium that creates its own unique approximations of our embodied existence, it borrows some of its signifying practices from other disciples. Film ‘combines its spatial qualities with rhythmic relationships comparable to those of music, poetry and dance’.66 The ability of film to amalgamate disparate visual, aural and temporal elements into a coherent aesthetic experience and harmonise a range of creative traditions, resonates with the ambitions of later installation practices. Here, the moving image rubs shoulders with multiple pictorial, performative, sculptural and digital artefacts, sometimes in an attempt to create a new hybridised art form, at others to maintain the disciplinary autonomy of each tradition.

Two opposing forces are at play within an installation: fragmentation and cohesion. The continuity of space is used to both contain and stage the internal drama of a work made up of disparate elements drawn from a range of disciplines. Sound, ambient as well as in the form of music and speech, is frequently mobilised for its synthesising properties in both cinema and installation. Where sound pulls together physically distinct elements in an installation, the audio track of a film is used as a smoothing device for linking one scene to the next and rationalising potentially illogical juxtapositions of locations and characters.

In the 1990s, there was a fashion for videos whose duration conformed to the two- to three-minute length of popular songs. Ann McGuire’s I am Crazy And You’re Not Wrong (1997) and Michael Curran’s Sentimental Journey (1995), for example, both defamiliarised well-known tracks with satirical performances to camera, but their actions were nonetheless contained by the continuity of the original song. As Amrit Gangar observed, ‘“song” …suggests an inbuilt rhythm, a metre, a composition that holds our attention’ and in this respect, music has the capacity to harmonise the most extreme visual dissonances an artist might throw at the screen.67 Within the jurisdiction of an installation, music can similarly placate warring elements, both on screen and set loose in the gallery space.

THE PERSISTENT ALLURE OF FILMIC ILLUSION IN AN AGE OF INSTALLATION

Film bequeaths to moving image installation the grammar of cinema, its structures of production and reception, its cultural history, as well as its material conditions. As we have seen, moving images have a dual nature; whilst consisting of nothing more than successive patches of light and aural disturbances, they are organised into a pictorial flow passing through a frame equivalent to a window onto another world, governed by the laws of perspective Leon Battista Alberti established in Renaissance painting. The aperture of the filmic frame reveals a dynamic and fugitive universe of movement and sound endowed with an uncanny likeness to our own and running in parallel with our lives. In this alternative universe what seems familiar in our own environment takes on unexpected qualities and affects; as Dimitri Kirsanoff has remarked, ‘each thing existing in the world knows another existence on the screen’.68 The enchantment of film, its ability to unlock the secrets of peoples, places and things ‘living their mysterious, silent lives alien to the human sensibility’69 seems to endow the spectator with second sight and this visionary dimension has guaranteed the enduring appeal of cinematic illusionism. Even at the height of the deconstructive project in the late twentieth century, when cinematic verisimilitude was the object of contestation and artists experimented with immersive, borderless projections such as Steve Farrer’s ‘frameless films’,70 or when they rejected narrative and visual pleasure altogether, reflexively drawing attention to the facts of matter in film, artists nonetheless remained enthralled to the wonders of cinematic mimesis.71

No artistic proposition could ever be made manifest for the consideration of an audience without splitting off the simulated spaces of the creative imagination from the real world. Artists have consistently reverted to the filmic frame for its capacity to demarcate and conjure up another reality of their own making, perhaps as a correlate of the self, experienced as a psychic space, an interior domain of emotions, dreams and fears. Writing in 1971, Annette Michelson proclaimed films ‘analogues of consciousness’, artefacts that allow audiences to reflect ‘on the conditions of knowledge’.72 Furthermore, they ‘facilitate a critical focus upon the immediacy of experience in the flow of time’.73 The bounded image also isolates the elements that snare artists’ interests in the external world enabling them to be summoned ‘out of the shadows of indifference’ onto the palette of artistic expression.74 For William Raban, the film frame also provides a material anchor to the processes of looking, for artist and viewer alike. Whilst the moving image focuses spectatorial attention, it also enables Raban to generate ‘thoughts on film’, giving testament to his creative endeavours and asserting his self-presence in a world of fragmented identities.75

Like the demi-gods of Greek mythology reconciling the differences between mortals and the divinity, we have developed the ability to move seamlessly between worlds, and it is this perceptual journeying that is dramatised in moving image installation. The gallery offers us a sanctuary in which to drift between the domain of the filmic imagination where Virginia Woolf found ‘thought in its wildness, in its beauty and in its oddity’ and the realm of observable reality, the world of things.76 As we progress through the spaces of an installation, in our crossings and returns, our cognitive faculties and our emotions travel with us, spilling from one perceptual sphere to the other, muddying the waters between the two.

1 Proto cinema refers to practices that employ technical or formal aspects of film without resolving into conventional projected works. This would include pre-cinematic optical devices.

3 Sean Cubitt (2013) ‘The Shadow’, MIRAJ, 2: 2, p. 188.

4 Duncan White (2013) ‘Media is sensational: Art and mediation in the experience economy’, MIRAJ, 2:2, p. 162. See also Jean Baudrillard (2011) Symbolic Exchange and Death. London: Sage.

5 Jean-Louis Baudry (1974) ‘Ideological Effects of the Basic Cinematographic Apparatus’, Film Quarterly, 28: 2, p. 47.

6 Shadow play has been a feature of many contemporary installation works by artists such as Gill Eatherley, David Dye and Nalini Malani.

7 Lucy Reynolds, ‘Magic Tricks?: The Use of Shadow Play in British Expanded Cinema’, paper given at Expanded Cinema – Activating the Space of Reception conference, Tate Modern, London, 17 April 2009.

8 Tom Gunning ([1989] 1994) ‘An Aesthetic of Astonishment: Early Film and the (In)Credulous Spectator’, in Linda Williams (ed.) Viewing Positions: Ways of Seeing Film. New Brunswick, NY: Rutgers University Press, p. 115.

9 Jean Epstein ([1923] 1981) ‘On Certain Characteristics of Photogénie’, trans. Tom Milne, Afterimage, 10, p. 14.

10 Rachel O. Moore (2012) ‘A Different Nature’, in Sarah Keller and Jason N. Paul (eds) Jean Epstein: Critical Essays and New Translations. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, p. 180. Available online: http://dare.uva.nl/document/361589 (accessed 19 November 2013).

12 Lucy Reynolds, op. cit.

13 Lucy Reynolds, op. cit.

14 I say ‘hallucinatory’, but I am one of many who believe they have seen a ghost. No scientific explanation has yet been posited that proves the image of the spectral woman I saw was simply the result of indigestion, atmospheric pressure or some photographic imprint embedded in the room in which nefarious events once took place.

15 Robert Smithson (1996) Robert Smithson: The Collected Writings. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press, p. 138.

16 I have discussed this notion in relation to Peter Campus’s work in ‘Peter Campus: Opticks’, MIRAJ, 1:1, pp. 107–10.

18 The Dutch artist Berndnaut Smilde has developed a similar obsession with clouds, but his trick is to generate the real thing indoors, with smoke and water vapour. These enigmatic weather systems evaporate within a few moments.

22 Persistence of vision is said to be retinal in that an afterimage lingers in the eye to compensate for blackout breaks in vision while blinking. Much argument has erupted around where the perception of motion takes place, in the eye or the brain, or within some complex interaction between the two.

23 In 2007, BBC2 used a zoetrope motif as an ident linking the evening’s programmes.

24 Tom Gunning (1986) ‘The Cinema of Attraction: Early Film, Its Spectator and the Avant-Garde’, Wide Angle, 8: 3/4, pp. 63–70. Gunning coined the phrase ‘cinema of attractions’ with Andre Gaudreault in 1985, but it was itself an adaptation of Eisenstein’s notion of a ‘Montage of Film Attractions’ from a 1920s essay of the same name.

25 A. L. Rees (1999) A History of Experimental Film and Video. London: British Film Institute, p. 17.

27 For a history of early cinema, see Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell ([1994] 2003 [2nd edn) Film History: An Introduction. New York: McGraw-Hill, pp. 13–32.

28 Tom Gunning, ‘An Aesthetic of Astonishment’, op. cit., p. 123.

29 Quoted by Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell, op. cit., p. 16.

30 Tom Gunning, op. cit., p.115.

33 Charles Musser (1986) Motion picture catalogs by American producers and distributors, 1894–1908 [microform]: a microfilm edition, Frederick, MD: University Publications of America.

34 Mario Slugan (2011) Some Concerns Regarding the Cinema of Attractions, working paper, p. 1.

35 The earliest colour was achieved by hand-tinting black and white film. The British two-colour system Kinemacolour was invented by George Smith in Britain and overtaken in the 1920s by the highly-saturated Technicolour, developed in America.

36 Raymond Bellour’s umbrella term developed out of his interest in ‘the mutations and exchanges between different image media’, and the development of installations that both ‘use cinema as an object’, including works based on found footage, and those made by filmmakers using their own imagery. See Raymond Bellour (2013) ‘“Cinema”, Alone/Multiple “Cinemas”’, Jill Murphy (trans.) Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media, 5. Available online: http://www.alphavillejournal.com/Issue5/HTML/ArticleBellour.html (accessed 15 July 2014).

37 Sergei Eisenstein ([1942] 1945) The Film Sense, trans. Jay Leyda. London: Faber and Faber, p. 14.

38 Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell, op.cit., p. 43.

39 See Noël Burch (1979) ‘Film’s Institutional Mode of Representation and the Soviet Response’, October, 11, pp. 77–96.

41 Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell, op. cit., p. 46.

42 See Thompson and Bordwell for a fuller account of the development of Hollywood film. op. cit.

44 Christian Metz (1977) Psychoanalysis and Cinema: The Imaginary Signifier, trans. Celia Britton, Annwyl Williams, Ben Brewster and Alfred Guzzetti. London: MacMillan.

45 Germaine Dulac interviewed by Paul Desclaux in Mon Cine, October 1923, (my translation), the original French quoted in Rosanna Maule (2002) ‘The Importance of Being a Film Author: Germaine Dulac and Female Authorship’, Senses of Cinema, 23. Available online: http://sensesofcinema.com/2002/feature-articles/dulac/ (accessed 7 October 2012).

46 A. L. Rees, op. cit. p. 30.

47 Germaine Dulac, op. cit., (my translation).

48 Henri Chomette quoted in A. L. Rees, op. cit., p. 35.

49 Anton Ehrenzweig ([1967] 1973 [2nd edn) The Hidden Order of Art. St. Albans: Granada, p. 14.

50 Clare Considine reports in The Guardian that synaesthesia is now ‘all the rage’ and ‘many musos are currently claiming [it] as their superpower’. Devotees include Nick Ryan who asserts that new technologies are creating a kind of ‘cultural sysnaesthesia’, making the ‘collision of the senses available to the masses’ (7 June 2014).

51 Barbara Hepworth interviewed by the BBC in the 1960s, re-broadcast in Abstract Artists in Their Own Words (Ben Harding, director), BBC4, 8 September 2014.

52 Iwona Blazwick speaking on Abstract Artists in Their Own Words, as above.

53 Robert Motherwell (1951) in What Abstract Art Means to Me, Bulletin of the Museum of Modern Art (New York), 18: 3, unpaginated.

54 See ‘The affects of the abstract image in film and video art’, roundtable discussion with Maxa Zoller, Bridget Crone, Nina Danino, Jaspar Joseph-Lester and Rubedo (2012), MIRAJ, 1: 1, pp. 79–87.

55 Sergei Eisenstein, op, cit., p. 181.

57 In the 1930s, the Hays Code governed ‘moral standards’ for films destined for general release. Many of the prohibitions relating to the depiction of ‘lustful embrace’ in ‘suggestive postures’ were avoided by the actors keeping one foot on the floor.

58 Gance’s projection technique anticipated the development in the 1950s of Cinerama in which three synchronised projectors created a panoramic image on a curved screen.

60 The painter J. M. W. Turner had himself lashed to the mast of a ship in a storm in order to better represent the scene in his painting Snow Storm (1842) – or so he claimed.

61 In Coir’ a’ Ghrunnda 360 (2007), the climber and artist Dan Shipsides scaled a remote peak in Scotland and attached a modified video camera to an 8-metre leash. By whirling the camera around his head, he expanded the reach of his kino-eye in the same way that in the 1920s Oskar Schlemmer defied the limits of his body in his Bauhaus performances by means of geometric body extensions.

62 The erasure of the human hand and eye from spectatorial awareness has been reversed to some extent in recent years, with a new fashion for hand-held, subjective camera styles in the mainstream. These are nonetheless married to solidly conventional narrative frameworks as witnessed in the recent BBC2 Cold War thriller Legacy (2013, Lucy Richer, director). The visuals were at times so hard to decipher that one was entirely reliant on the sparse dialogue to follow the story.

64 Bill Viola quoted by Chris Darke (2000) Light Readings: Film Criticism and Screen Arts. London and New York: Wallflower Press, p. 183.

65 Jean Goudal (1925) ‘Surrealism and Cinema’, reprinted in Paul Hammond (2000) The Shadow and its Shadows: Surrealist Writings on the Cinema. San Francisco: City Lights, pp. 49–56.

66 Kristin Thompson and David Bordwell, op. cit., p. 90.

67 Amrit Gangar (2012) ‘The moving image: Looped, to be Mukt! – the Cinema Prayōga conscience’, MIRAJ, 1: 2, p. 199.

68 Dimitri Kirsanoff (1926) ‘Problèmes de la photogénie’, in Cinéa-Ciné pour tous, 62, 1 June, p. 10.

69 Jean Epstein ([1923] 1988) ‘On Certain Characteristics of Photogénie’, trans. Tom Milne, in Richard Abel (ed.) French Film Theory. Princeton, CT: Princeton University Press, p. 317.

70 In The Machine (1978–88), Farrer recorded and projected ‘frameless, uninterrupted 360 degree sweeps onto 35mm cine film creating frameless, continuous recordings of time and space’; Michael Maziere (2007) The Dispersed Subject. Available online: http://www.academia.edu/413002/The_Dispersed_Subject (accessed 16 July 2014).

71 Farrer’s breathtaking circular projections may have ‘activated the space of projection’, as the structural film maxim decreed, but they did so by means of figuration with shapes resolving into likenesses of individuals and then fading away into a penumbral landscape.

72 Annette Michelson (1971) ‘Toward Snow: Part I’, Artforum, 9: 10, p. 172.

75 William Raban in conversation with the author, sometime in 2010.