One

BEFORE CONSTRUCTION

Protecting a beautiful view and creating economic growth was the initial goal behind the construction of Skyline Drive and Shenandoah National Park.

By 1700, nearly 68,000 inhabitants lived in the Blue Ridge Mountains of Virginia. First documentation of exploration materialized in 1716, when Gov. Alexander Spotswood traveled up the Rappahannock River. This area became officially recognized and land grants were issued encouraging Virginians to make this area their home.

Early American roads were nothing more than trails that had been widened for wagons. Very few had gravel. One of the most famous early roads was the Great Wagon Road. Hordes of early German and Scotch-Irish settlers used what became known as the Great Wagon Road to move from Pennsylvania southward through the Shenandoah Valley, through Virginia and the Carolinas, to Georgia, a distance of about 800 miles. The mountain ranges to the west of the valley are the Alleghenies, and the ones to the east constitute the Blue Ridge chain.

Once invented, the automobile changed the country. Clubs called auto clubs developed and began asking for roads into our national parks. The first park with roads was Yellowstone. Then came the request for the Blue Ridge Parkway.

This chapter contains photographs of mountain folk, farmland before it was acquired, early mountain roads, and Civilian Conservation Corps camps and enrollees.

The CCC boys did not construct the roadbed of the parkway, as you will see in chapter two; contractors did most of the roadbed work. They graded slopes and did most of the landscaping by planting thousands of trees and shrubs and acres of grass to landscape on both sides of the road. They built guardrails, guard walls, and overlooks.

EARLY ROAD IN 1909. Roads in the early 1900s were treacherous with deep ruts. Each road was maintained by hand, like this one in the Western Mountains of North Carolina. In 1908, Henry Ford introduced the first Model T, changing the way Americans dreamed of traveling forever. By 1916, the Federal Aid Road Act had been passed, funneling funds to states for road building. (North Carolina State Archives Photograph Collection.)

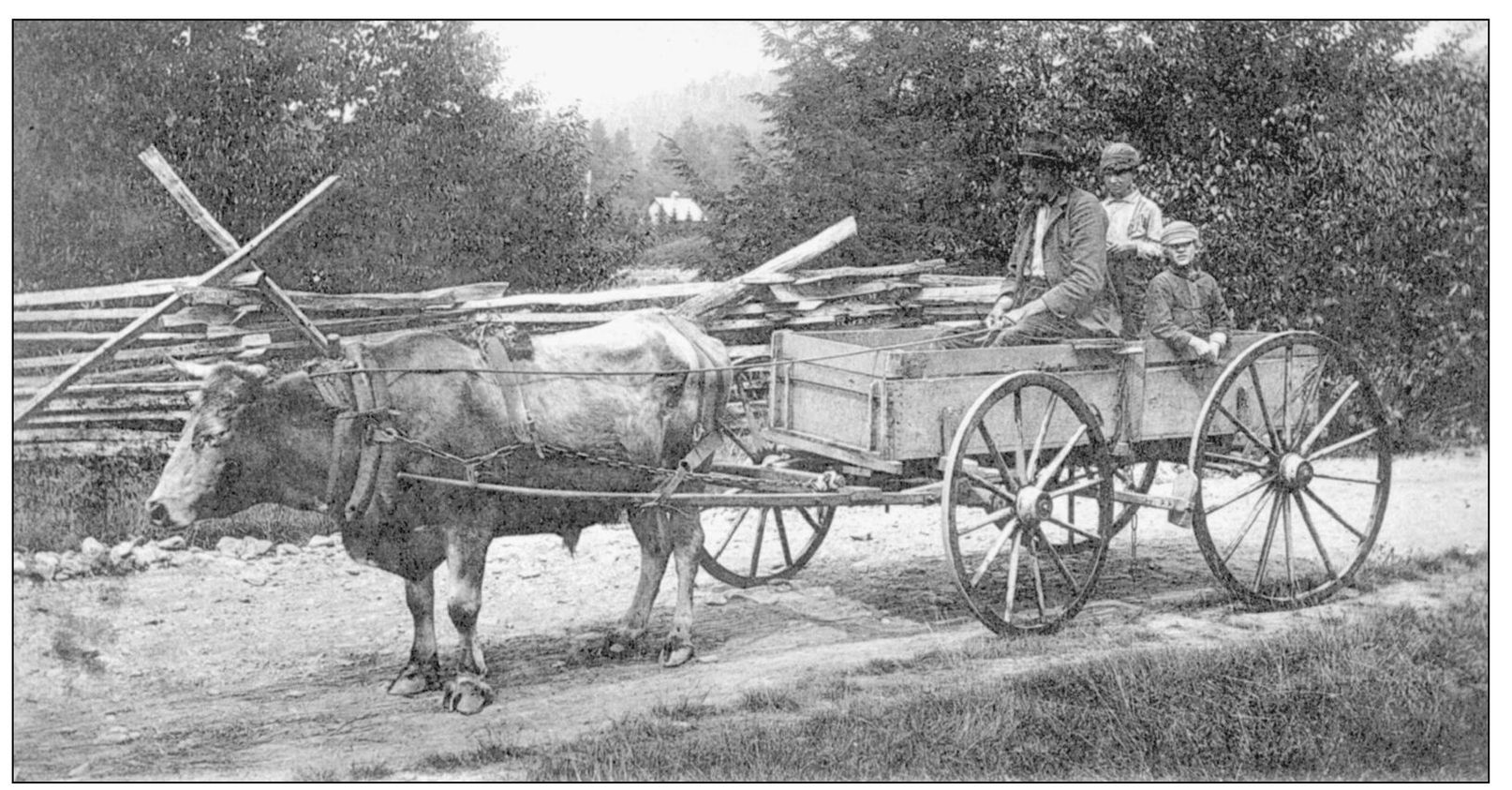

BURKE COUNTY OX AND CART IN 1906. Transportation for farmers consisted of oxen in the 1800s and early 1900s. They are powerful animals and could pull heavy loads, even in the mud. This photograph shows a Burke County, North Carolina, farm family heading to town in their family wagon, pulled by a team of oxen. (North Carolina State Archives Photograph Collection.)

BOONE PICNIC IN THE EARLY 1900S. Traveling to the mountains for a Sunday picnic was a tradition long before the construction of the Blue Ridge Parkway. This photograph shows a group of young people that have hiked up to the top of one of the high peaks in Boone, North Carolina. (Courtesy of Historical Boone.)

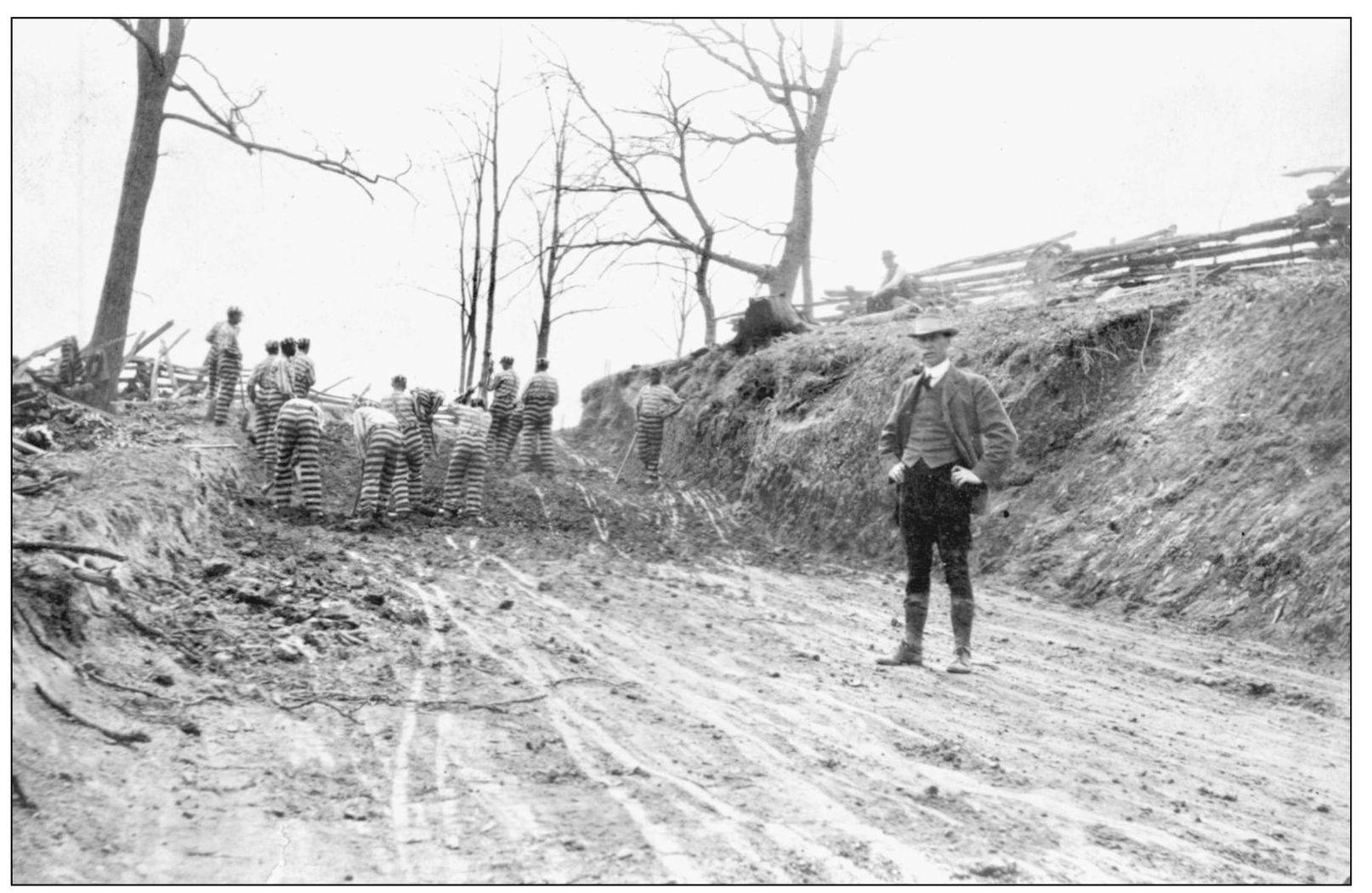

CHAIN GANG IN 1930. This photograph, taken in the early 1900s, shows a chain gang doing road maintenance. Chain gangs performed menial tasks like chipping rocks for roadbeds. It is doubtful that any chain gangs worked on the construction of the Blue Ridge Parkway. By 1955, chain gangs were phased out in the United States. (North Carolina State Archives Photograph Collection.)

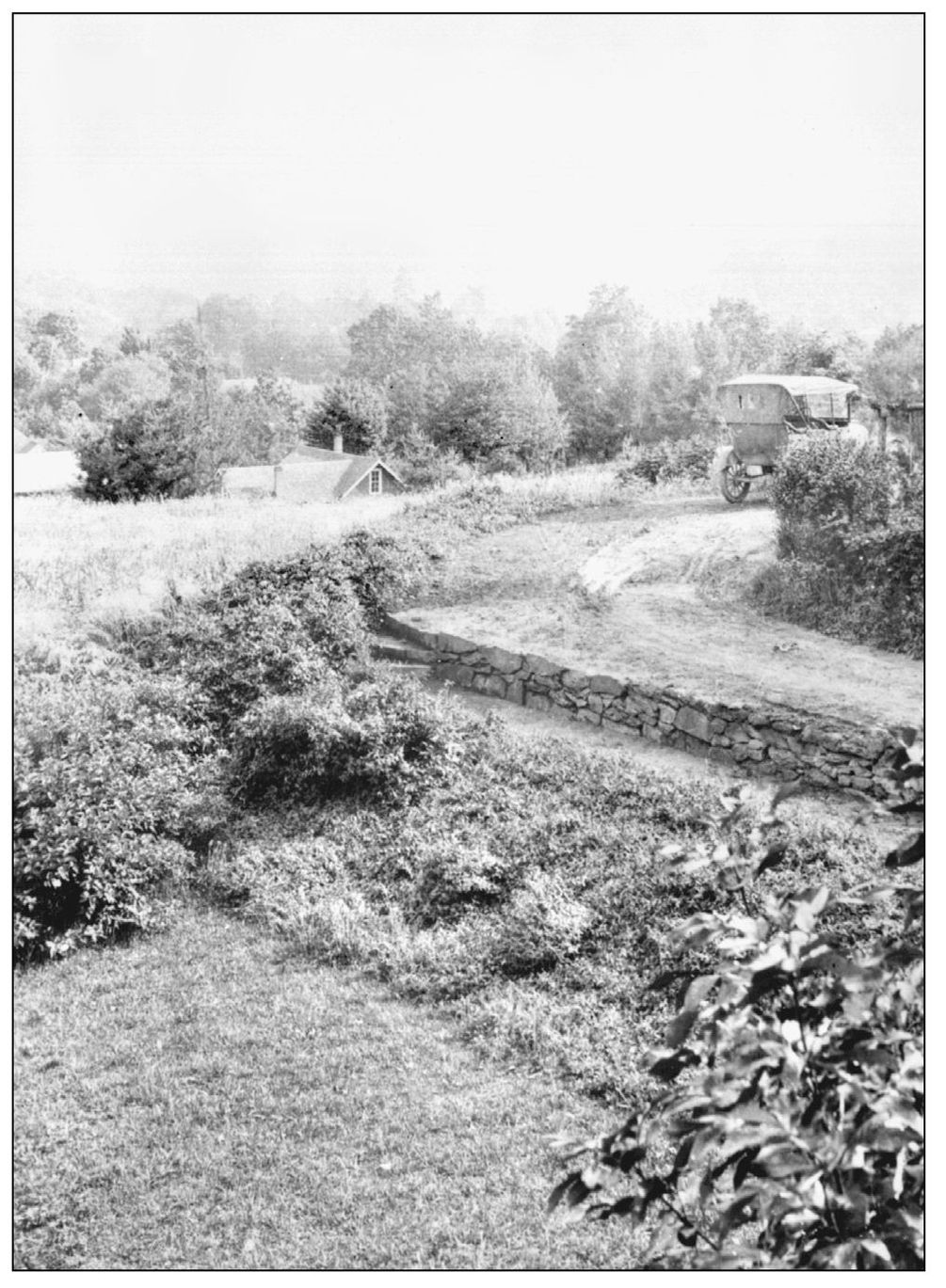

OLD MOUNTAIN ROAD IN 1913. This 1913 photograph of an automobile turning the curve was taken on the road in the Blue Ridge Mountains. Mr. Pratt’s road was surveyed and constructed near Linville, North Carolina. (North Carolina State Archives Photograph Collection.)

MRS. MACE ON FEBRUARY 14, 1913. A Sunday afternoon walk or picnic surely raised the curiosity of locals wanting to know what this new Blue Ridge Highway would look like. On February 14, 1913, this photograph was snapped of an older couple, Mrs. Mace and a friend, checking out the road in Western North Carolina. (North Carolina State Archives Photograph Collection.)

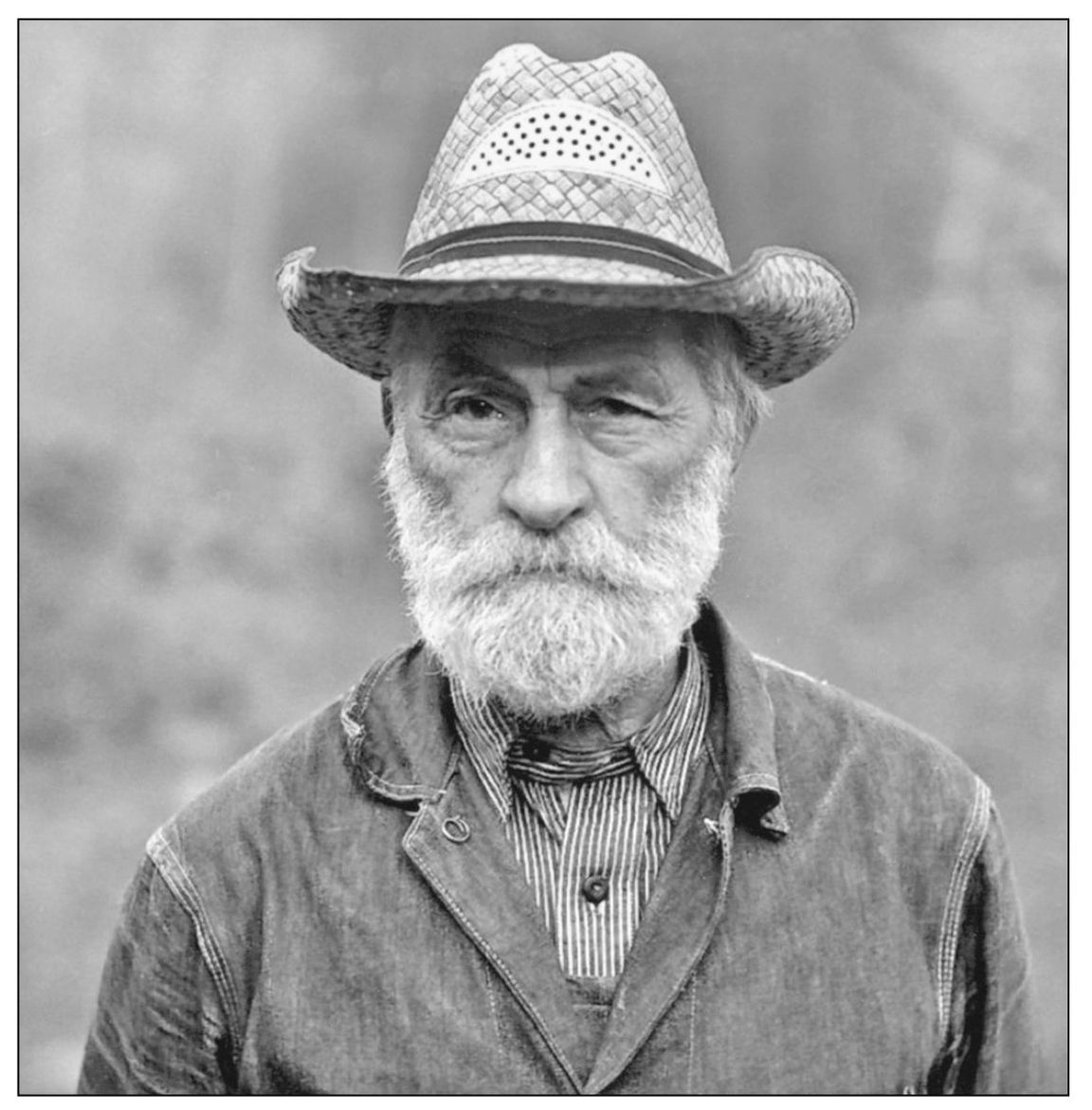

RUSS NICHOLSON IN OCTOBER 1935. Landowners like Russ Nicholson of the Shenandoah Valley either had to sell or donate their land taken for the path of the Skyline Drive and the Blue Ridge Parkway. Russ lived in Nicholson Hollow, where his ancestors had settled 200 years earlier. Deeds and rights-of-way had to be acquired before construction could begin. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

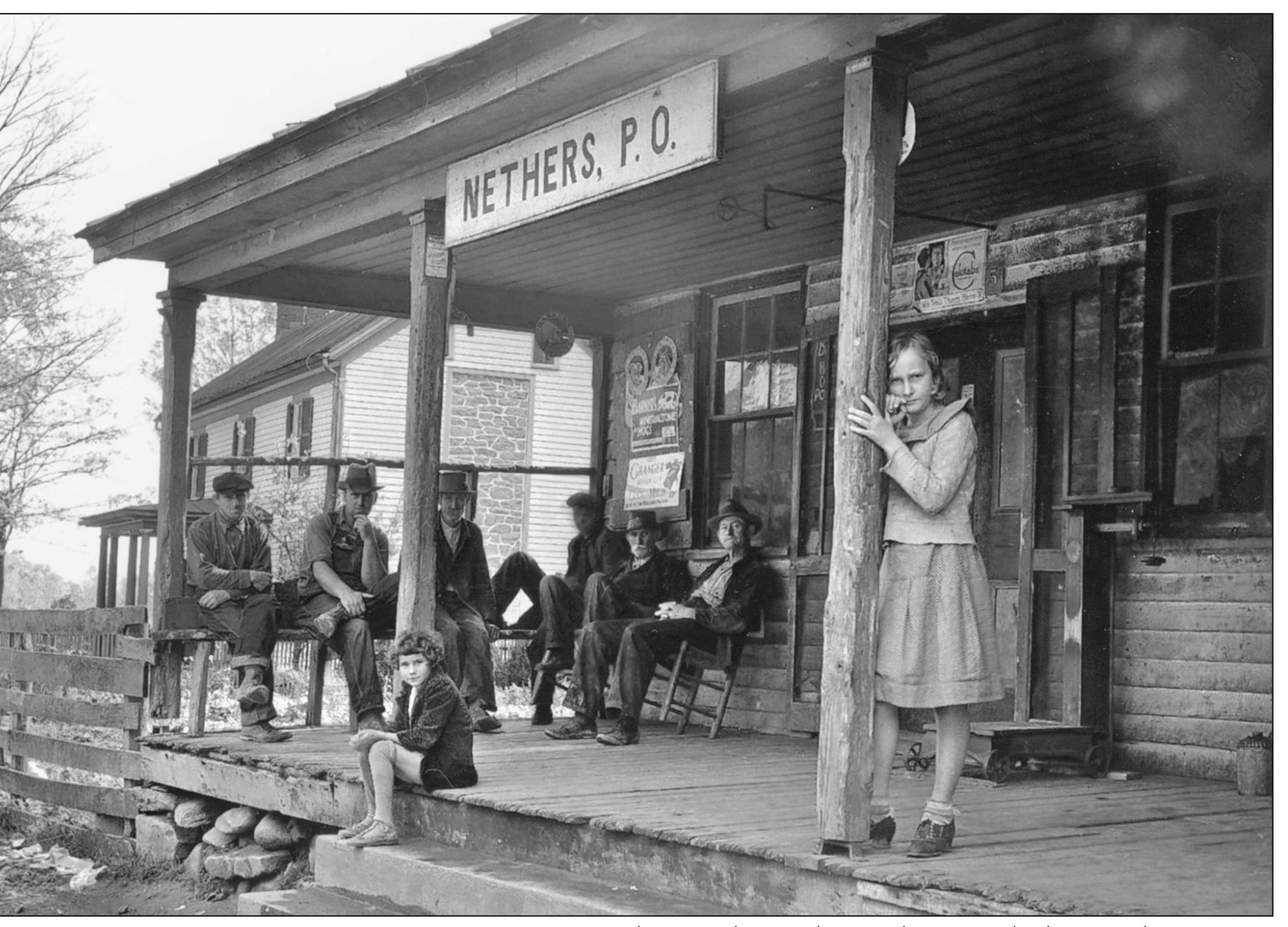

NETHERS POST OFFICE IN OCTOBER 1935. Photographer Arthur Rothstein took photographs of the resettlement folks of the Shenandoah Valley for the Farm Security Administration. The story of the Blue Ridge Parkway construction cannot be told without telling the story of the people. Limited photographs are available of the people who lived along the mountain tops that became the Blue Ridge Parkway; thus, photographs from the Shenandoah Skyline Drive have been used here to illustrate an important piece of history. This is one of his photographs showing the outside porch of the Nethers, Virginia, post office. The Farm Security Administration (FSA) was the Resettlement Administration in 1935 as part of the New Deal. It was an experiment in collectivizing agriculture—that is, in bringing farmers together to work on large government-owned farms using modern techniques under the supervision of experts. The program failed because the farmers wanted ownership, and the agency was transformed into a program to help them buy farms. The FSA bought out small farms that were not economically sound and combined them with about 33 other farms in a co-op type of situation where the farmers lived in a community and worked together. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

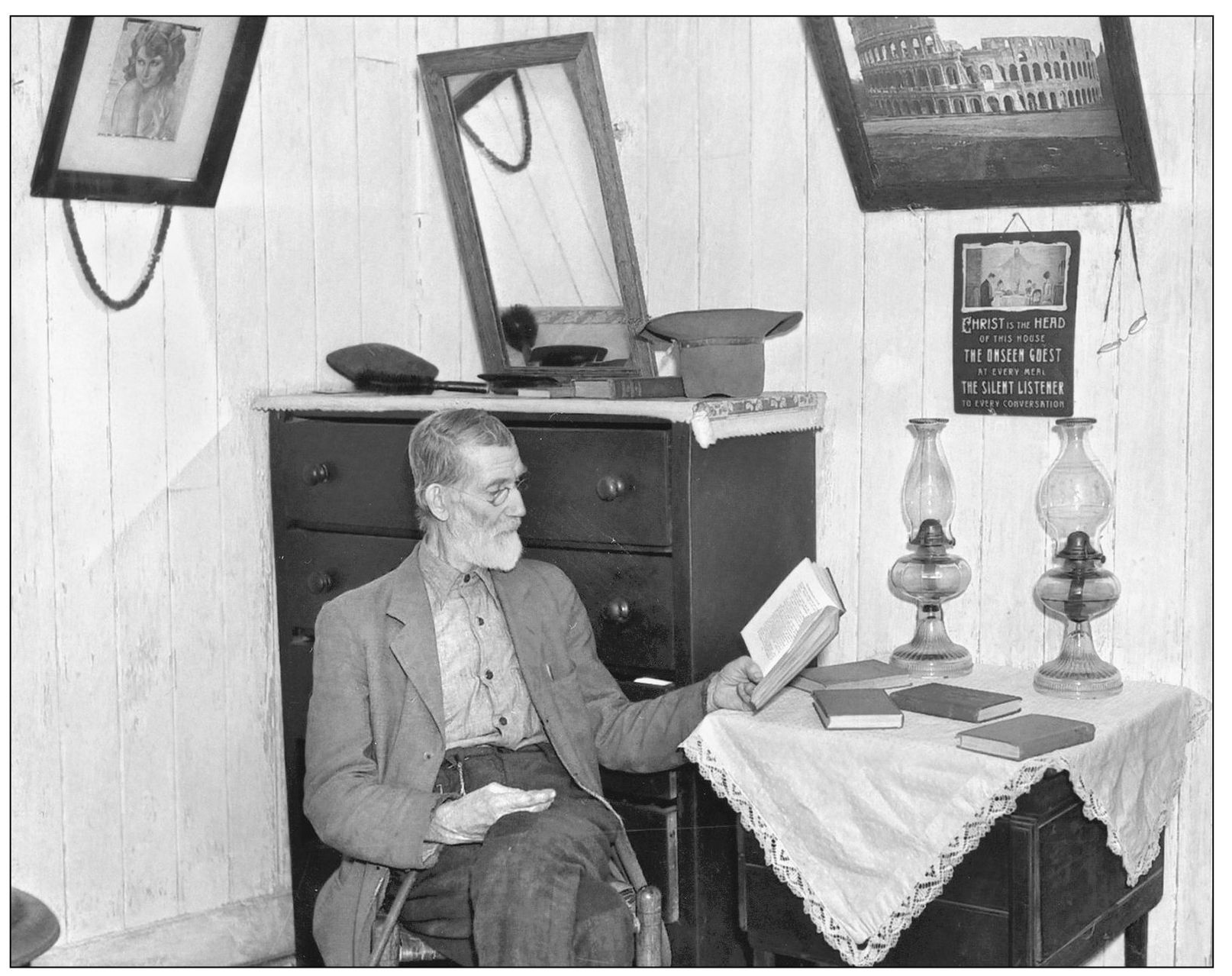

INTERIOR POSTMASTER’S OFFICE IN OCTOBER 1935. This photograph shows the interior of the postmaster’s home-based office in Nethers, Virginia. The postmaster played a very important role in rural America. He faced the challenge of delivering the mail over all types of terrain and weather conditions. (Courtesy of the Library of Congress.)

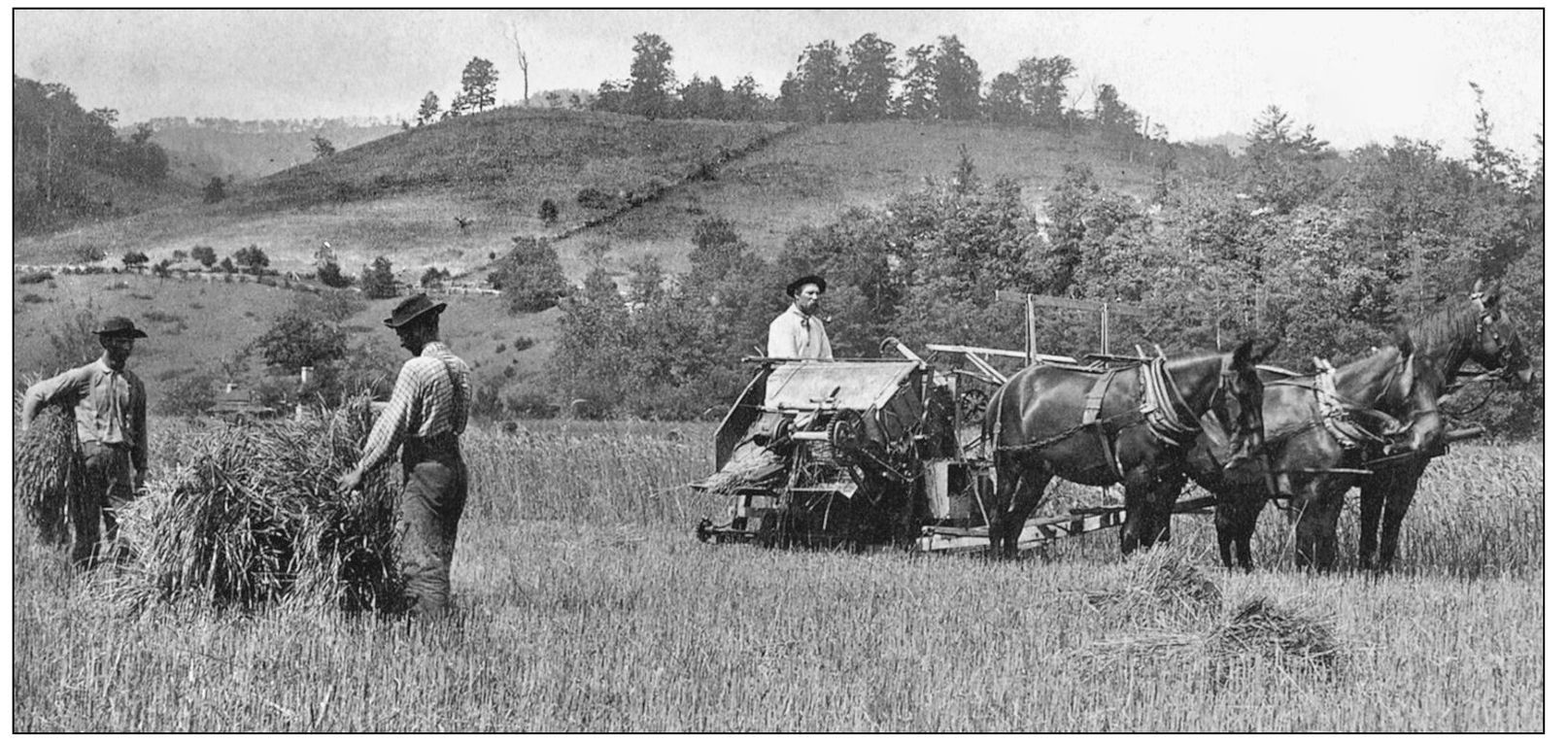

WHEAT THRESHING ABOUT 1920. Farming in Boone, North Carolina, in the early 1900s required a lot of actual horse power and man power. Before the tractor became an affordable piece of equipment, farmers had to do a lot of the work by hand. This is the type of farm that the Blue Ridge Parkway traversed after construction. (Courtesy of Historical Boone.)

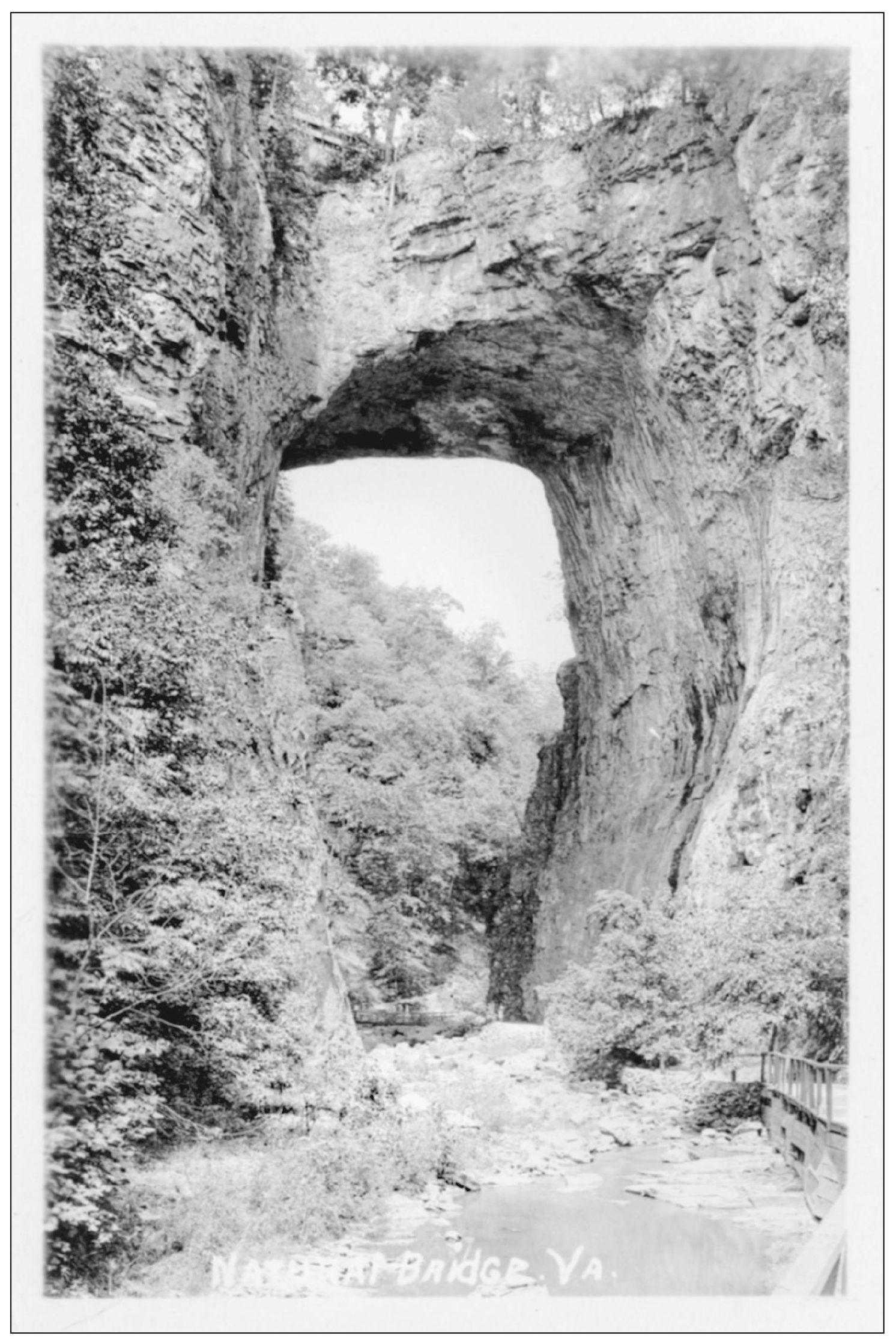

NATURAL BRIDGE AROUND 1910. Originally, the Natural Bridge was supposed to be part of the Blue Ridge Parkway. As it stands, the parkway was shifted several miles east, a short distance from the natural wonder. Today this spot boasts a motel, visitor center, and wax museum. (Courtesy of Karen Hall.)

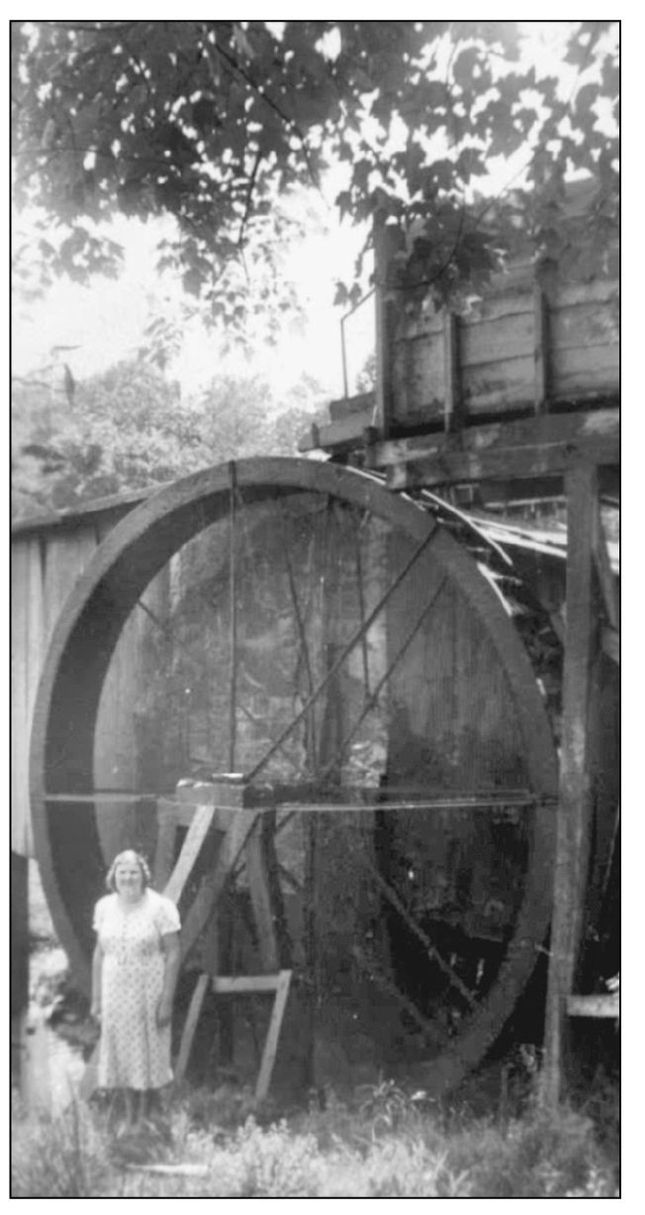

AN OLD MILL. This photograph of Estelle O. McDaniel near an old mill was taken in the early 1950s during a Sunday outing. Historically gristmills contained rotating stones powered by water or by wind. Mabry Mill at milepost 176.1 on the Blue Ridge Parkway is powered by water. (Courtesy of the Hardy family.)

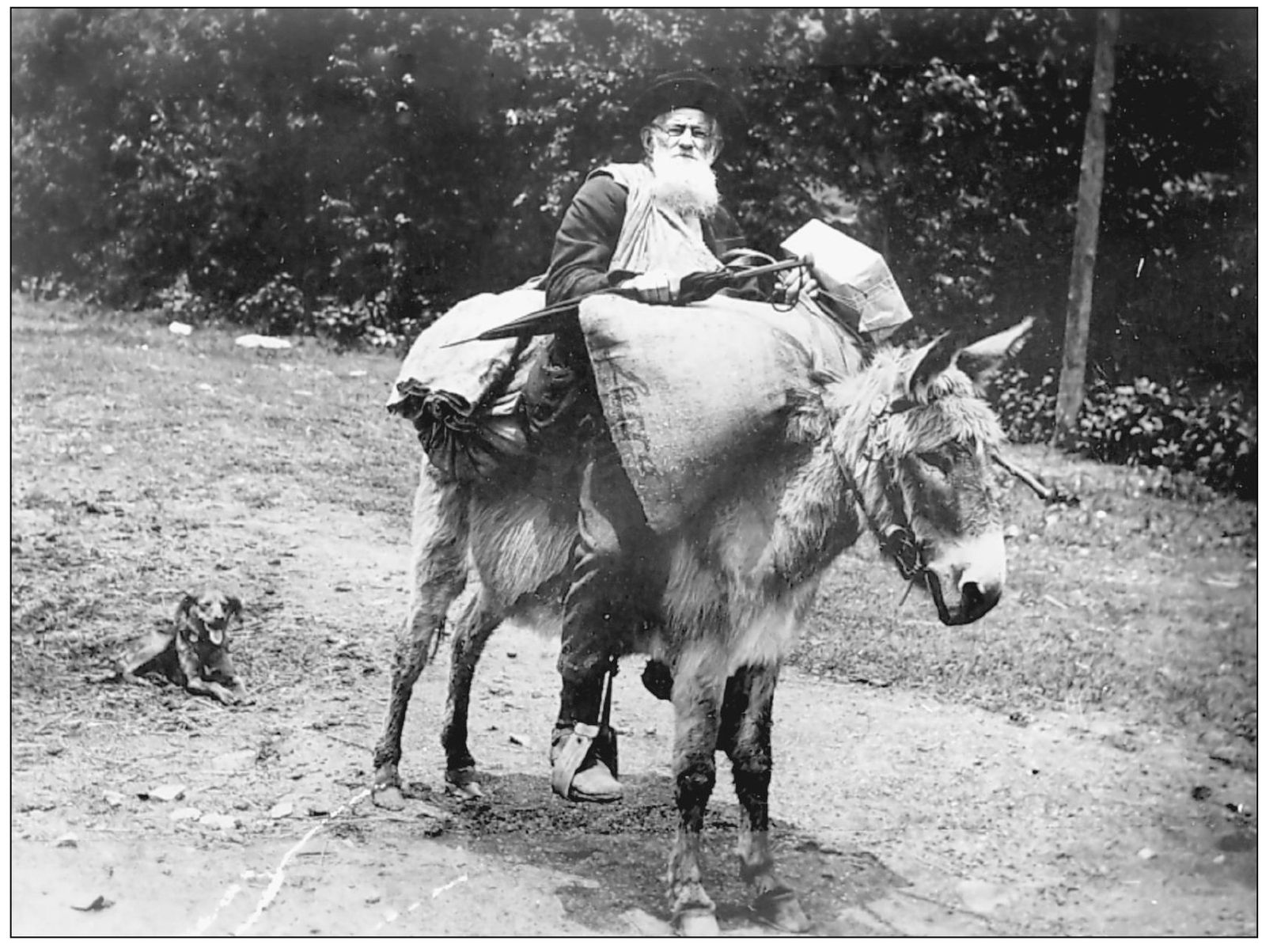

MOUNTAIN MAN AND DONKEY IN EARLY 1900. Donkeys and pack mules were important for hauling supplies in the 1800s. They were cheaper than horses and stronger for hauling loads. They also need less food than horses. Donkeys have developed very loud voices, which can be heard over several miles. They can defend themselves with a powerful kick of their hind legs. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

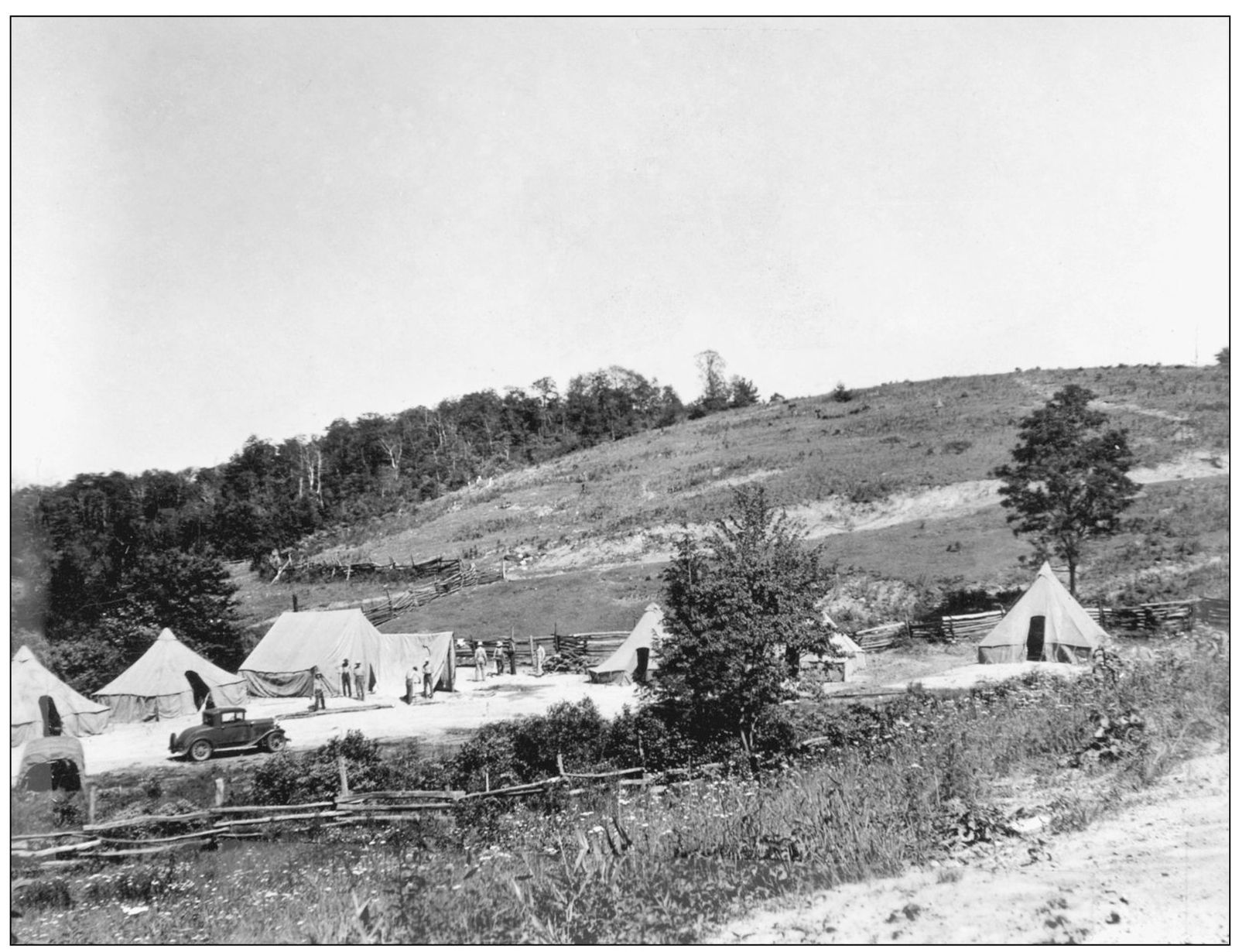

CCC MOVING IN TO DOUGHTON PARK IN JUNE 1938. The Civilian Conservation Corps were part of the New Deal, arranged by Franklin D. Roosevelt for economic relief during the Depression. This is one of the first camps set up for construction of the Blue Ridge Parkway. It was in Bluff Park, which is now Doughton Park, milepost 238.6. Landscaping was their main function. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

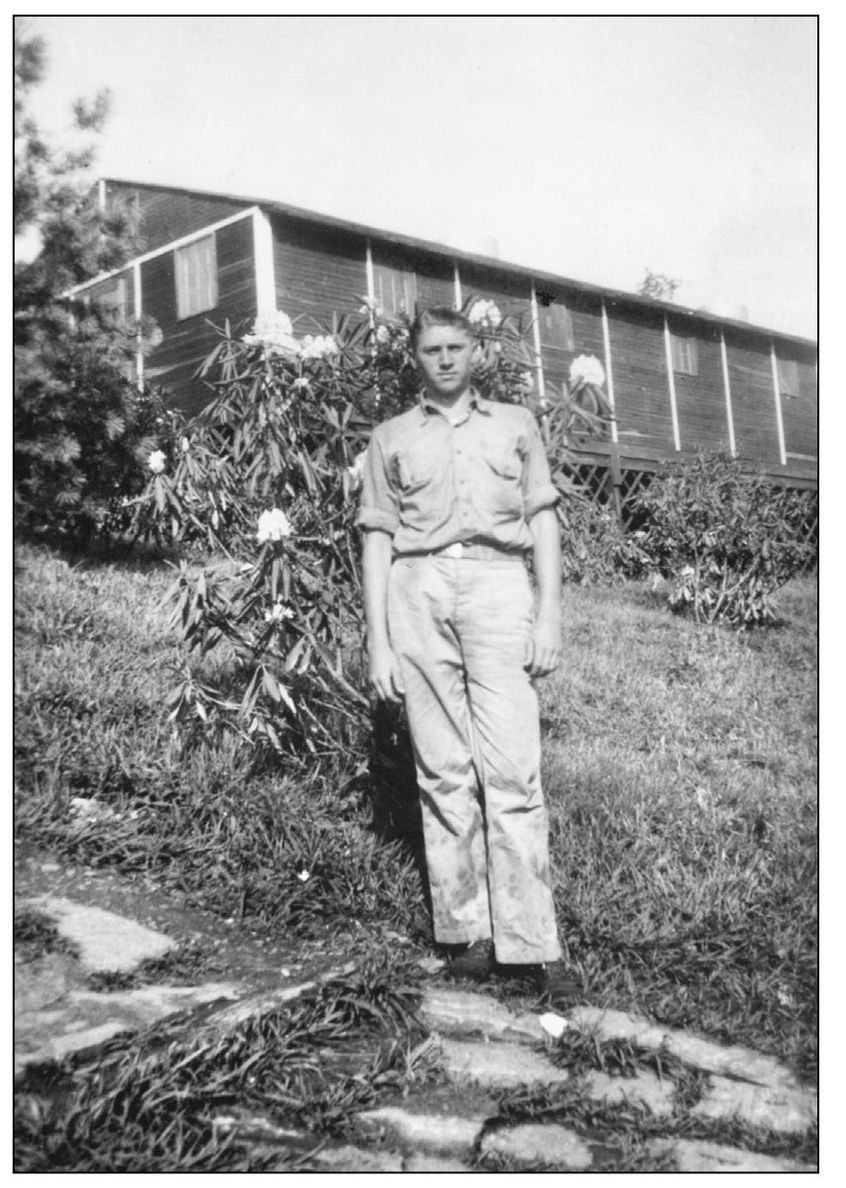

SAM LOWE IN 1940. Sam Lowe was an enrollee at the Doughton Park CCC camp in Laurel Springs, North Carolina. You can see one of the barracks behind him. He would have learned work skills to take to the work world when the CCC was disbanded. The men worked 8 hours per day for a total of 40 per week. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

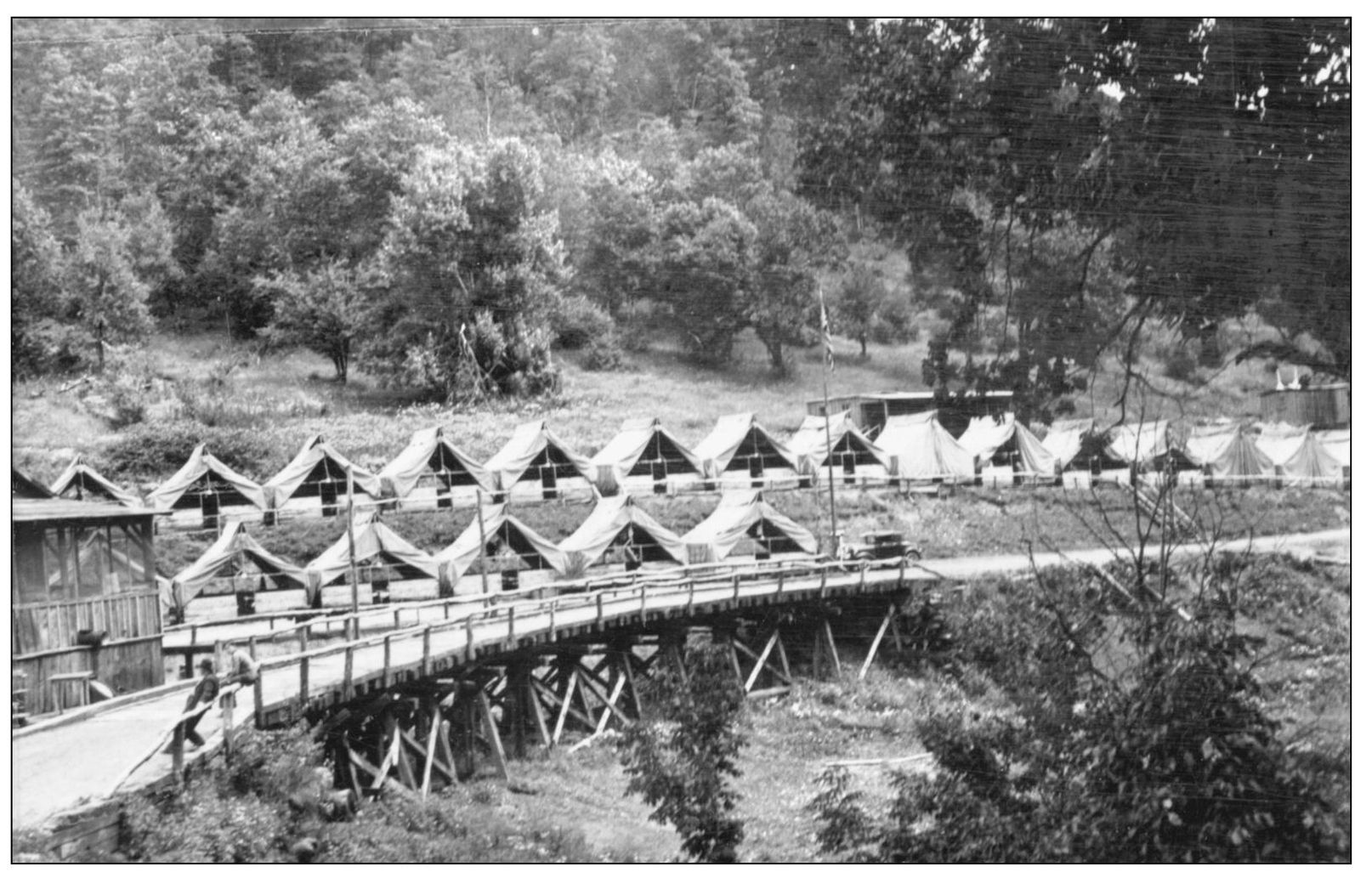

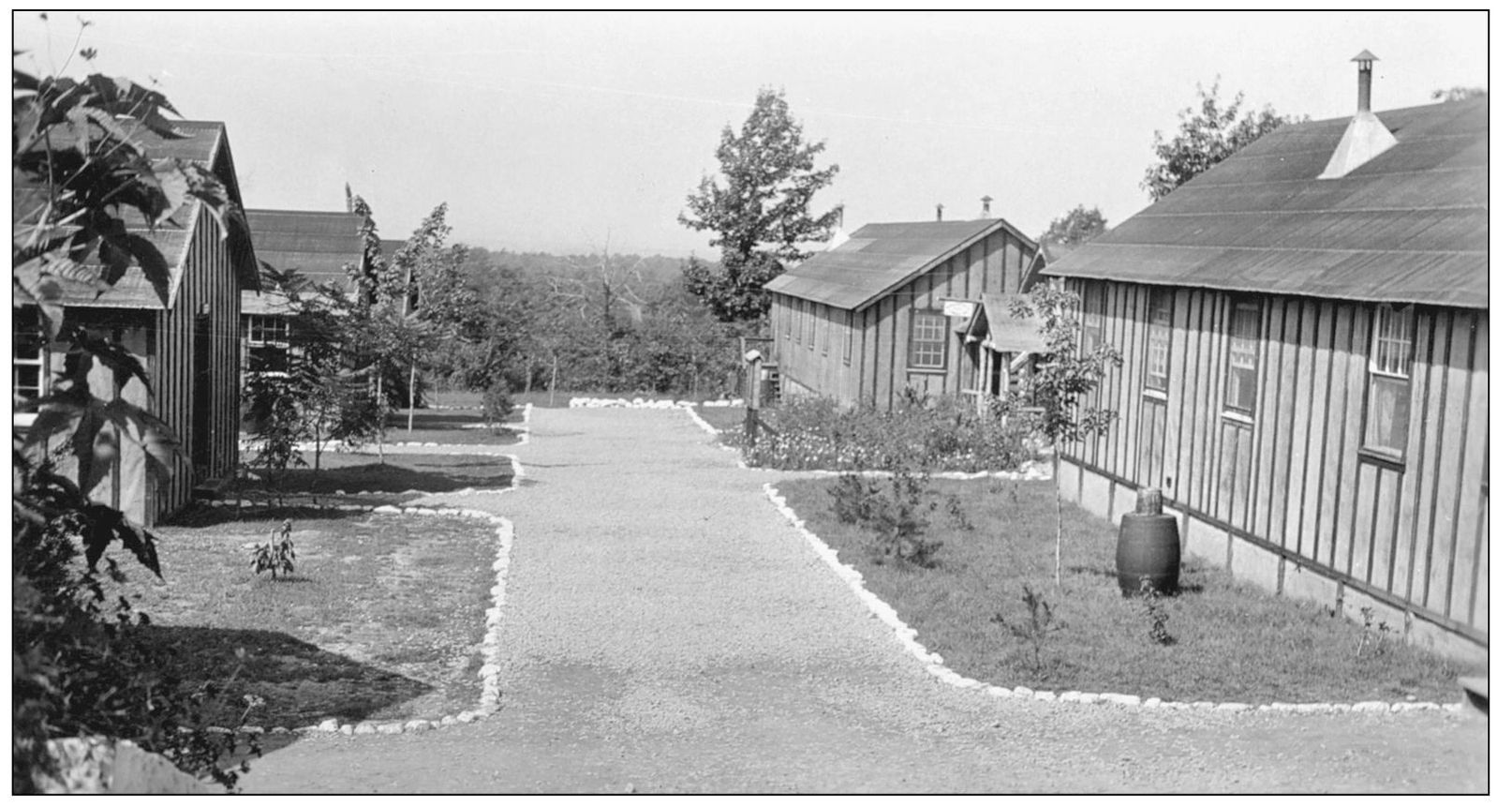

CCC COMPANY OF DOUGHTON PARK IN 1940. In this photograph, one can see that the camp is more established—with buildings instead of tents. The buildings would have included living barracks, a library, mess hall, storage facilities for equipment, and a recreational facility. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

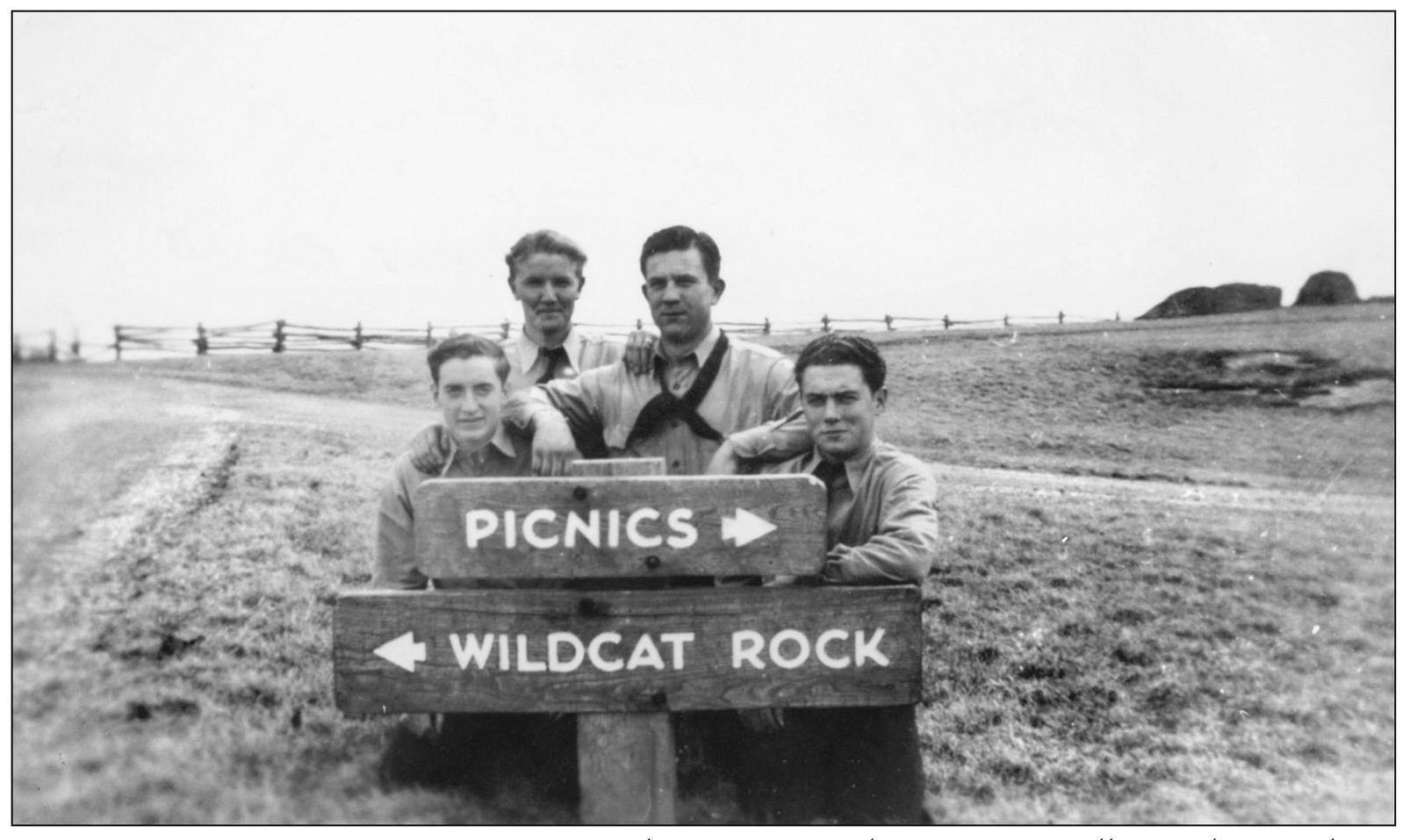

ENROLLEES OF DOUGHTON PARK IN 1940. These young gentlemen were enrollees at the Doughton Park CCC camp in Laurel Springs, North Carolina. From left to right, they are identified as Dale Shepherd, unidentified, Travis Owens, and Arthur Phipps. They are standing at a directional sign showing the way to the picnic area or the trail to Wildcat Rock. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

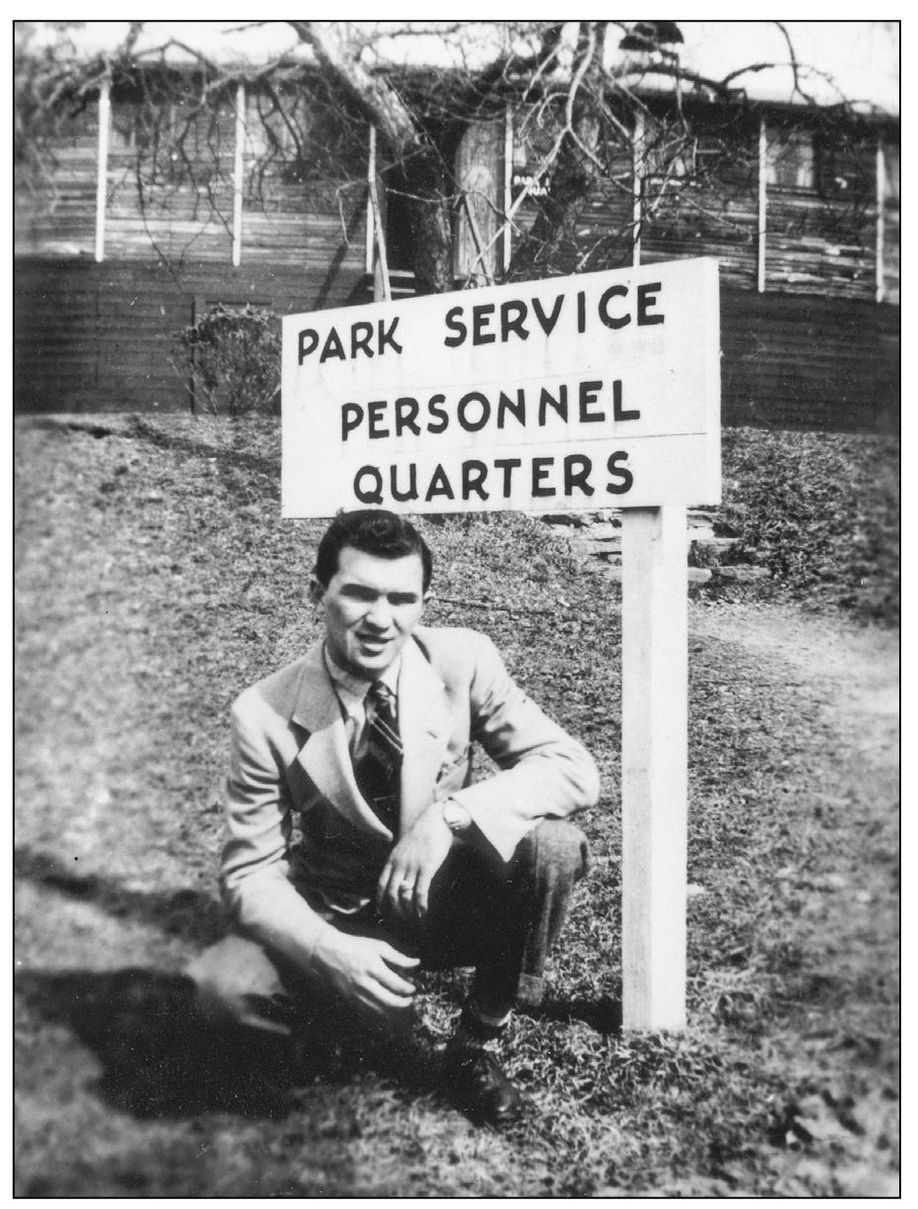

PETE KULYNYCH IN 1940. Pete Kulynych became administrative assistant with Lowe’s Hardware in North Wilkesboro, North Carolina, after leaving the CCC. The purpose of the CCC was to hire local boys and train them in usable skills. Most of their work projects included landscaping, but they also built comfort stations, guttering, and slope grades. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

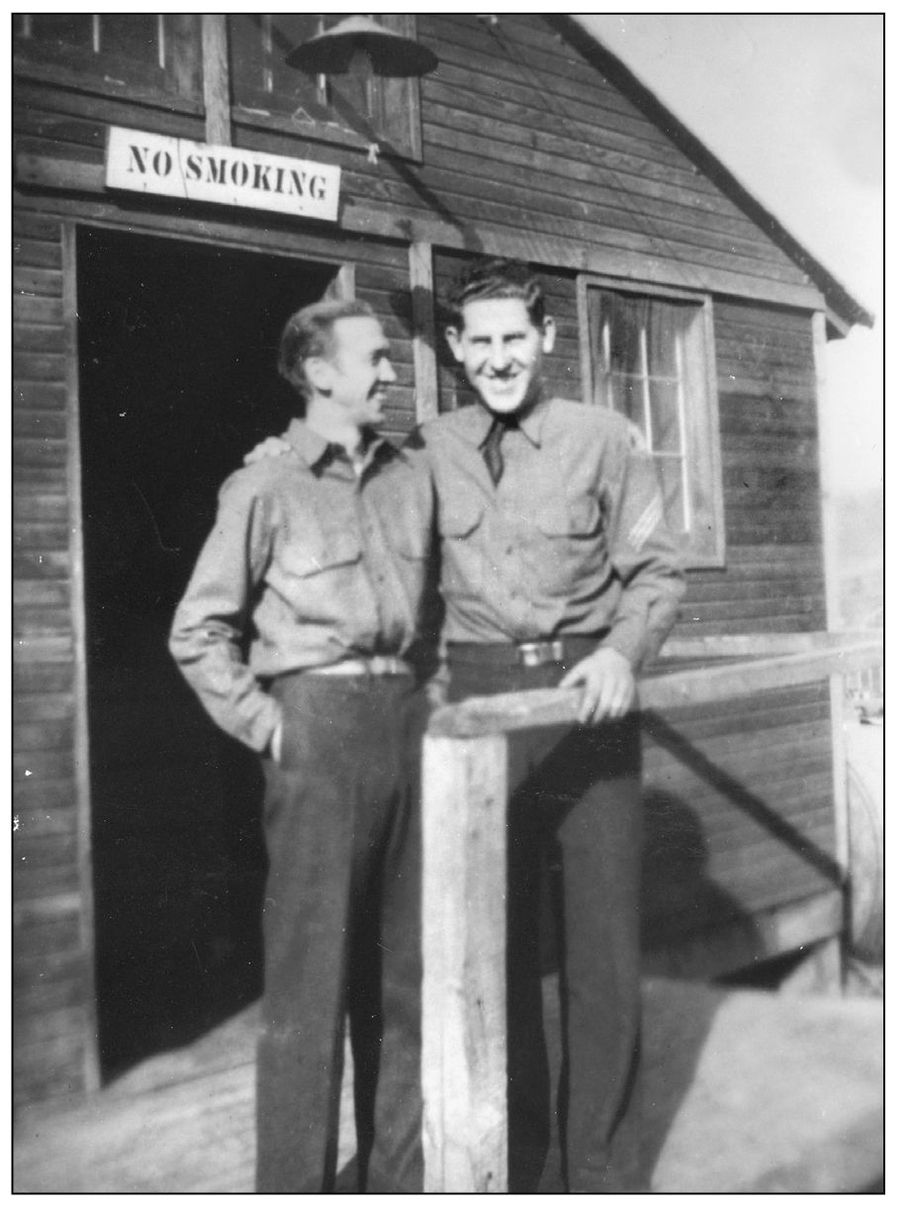

CCC ENROLLEES IN 1940. From left to right, these young men are Bert Richardson and Robert Wagoner. They were stationed at the Doughton Park CCC camp in Laurel Springs, North Carolina. Richardson was a native of the Blue Ridge Mountains. Local boys had to fill out an application and go through an interview process to be employed by the CCC. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

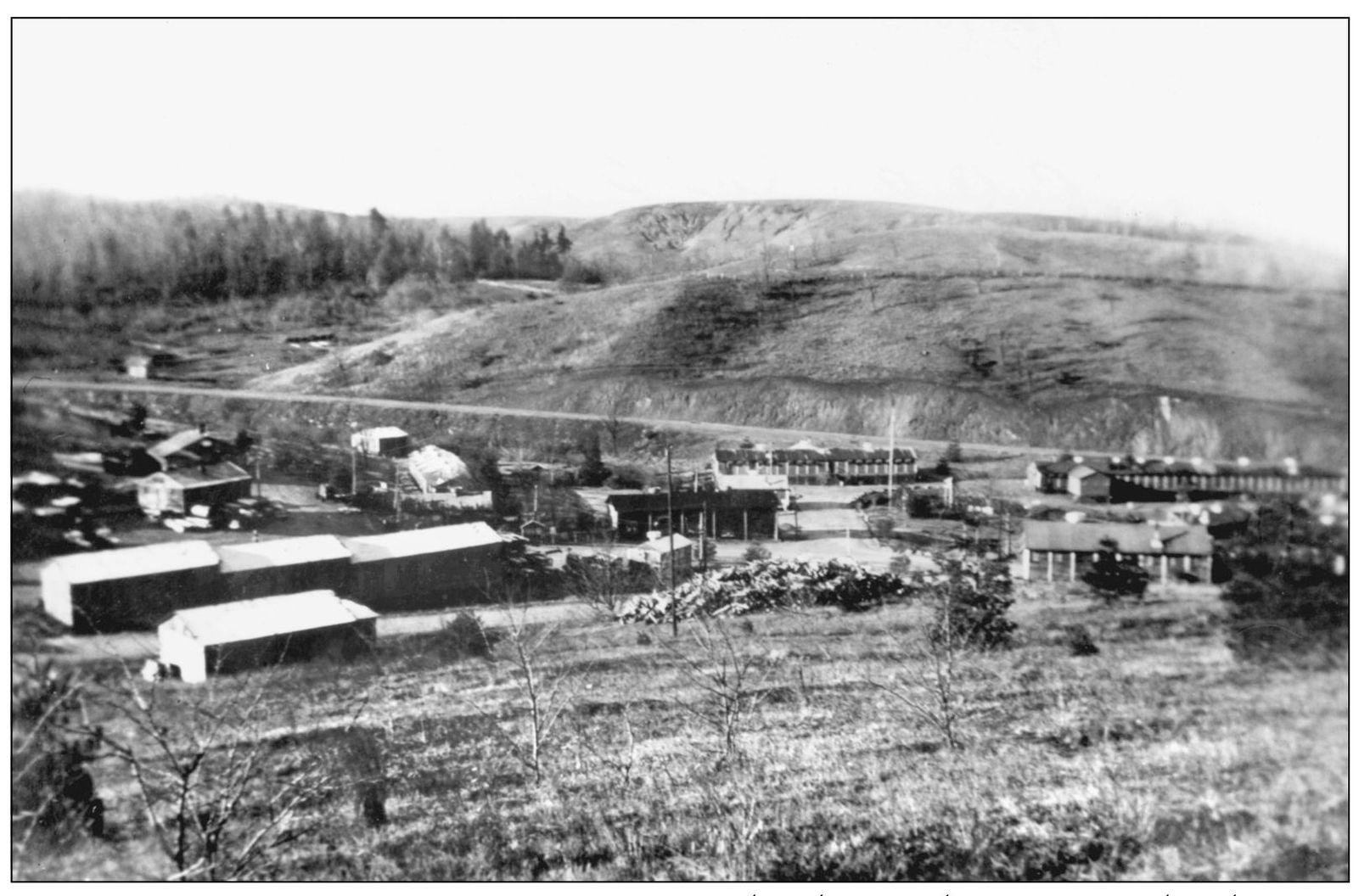

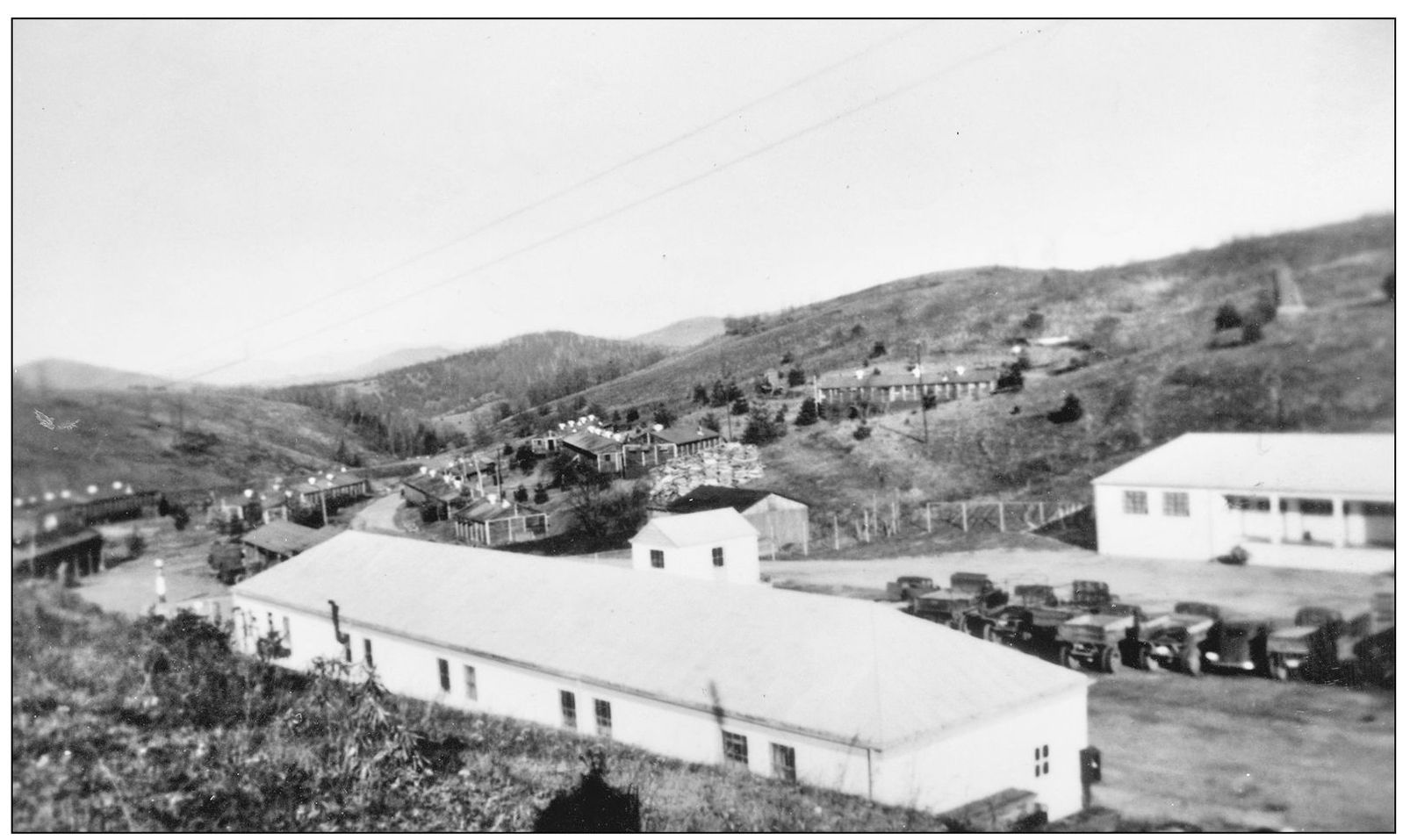

CCC CAMP AT DOUGHTON PARK IN 1940. This is a great example of how the CCC camps developed into a small community for the young men that enrolled with them. At least 17 buildings can be counted in this photograph. Buildings were premanufactured at a plant in Virginia so that they could be disassembled and reassembled if needed. After the end of the CCC, buildings were dismantled and the lumber was recycled. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

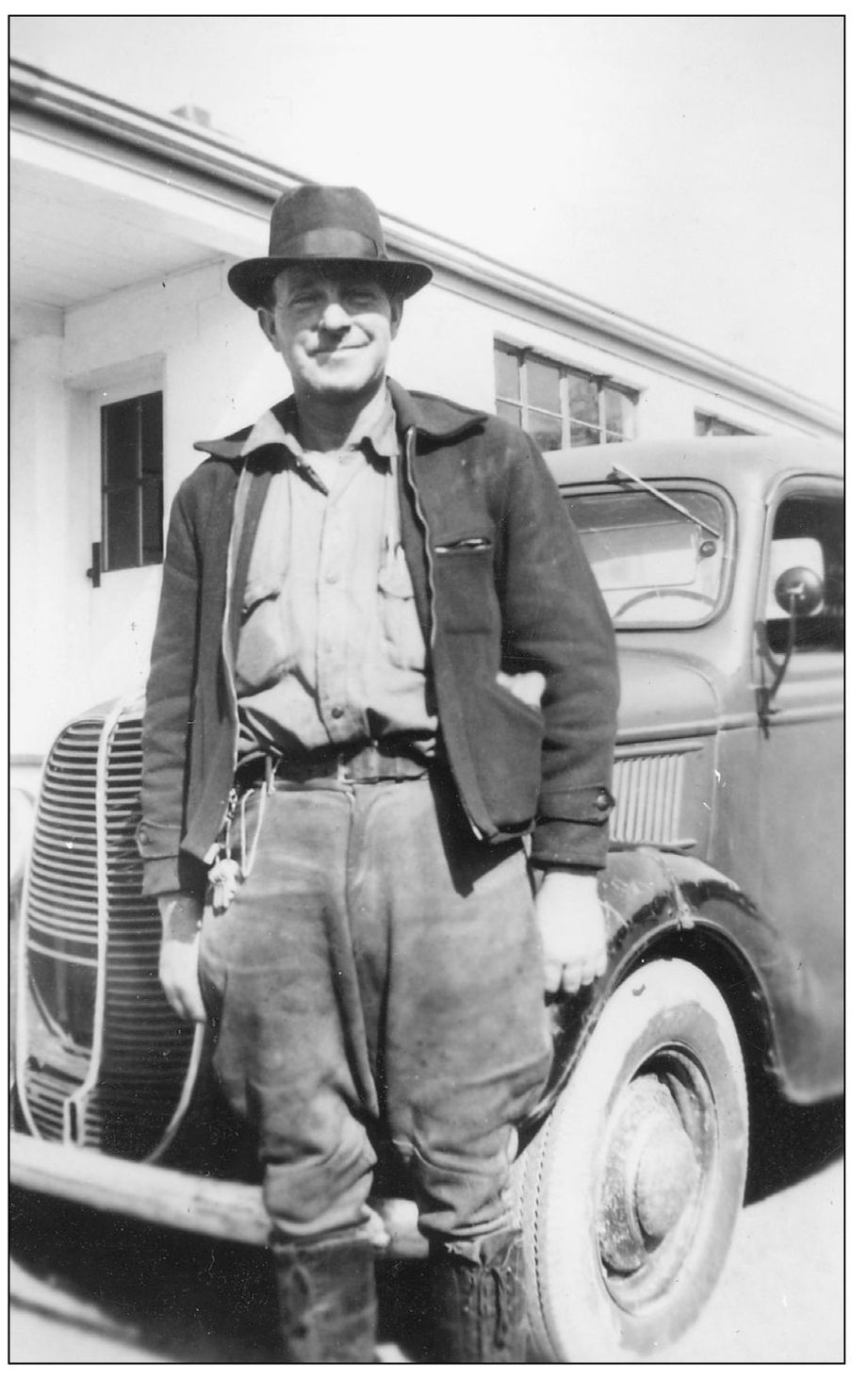

ED CARICO IN 1940. Ed Carico is thought to have been one of the foremen at the Doughton Park CCC camp. He is standing next to a vintage truck that would have been his means to travel from project to project directing the men. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

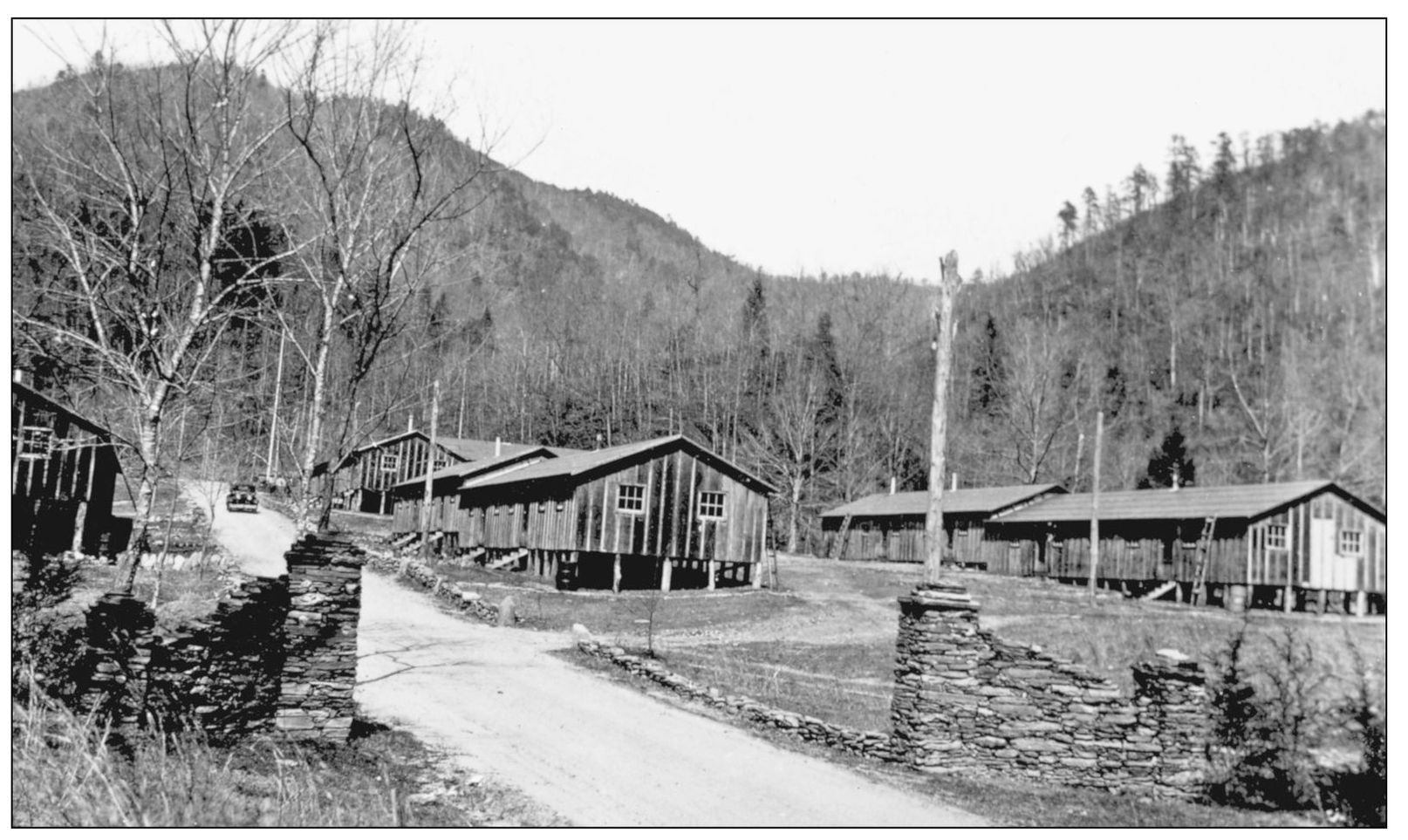

CURTIS CREEK CAMP ON APRIL 15, 1936. Curtis Creek Camp, located near Old Fort, North Carolina, was a Forestry Service Camp in McDowell County. Most of the CCC buildings were treated with creosote, a chemical that preserves the wood from insects and weather. The men from this camp helped the CCC camps on the parkway with tree planting and forest-fire management. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

ROCK CASTLE GORGE CAMP ON MAY 23, 1938. Located within 3.2 miles from the Rocky Knob picnic area in Floyd County, Virginia, the Rock Castle Gorge Camp had enrollees that would have built the trails, comfort stations, and picnic areas. The overlook for Rocky Knob would have been built near this camp. All that is left of this camp today are the building foundations. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

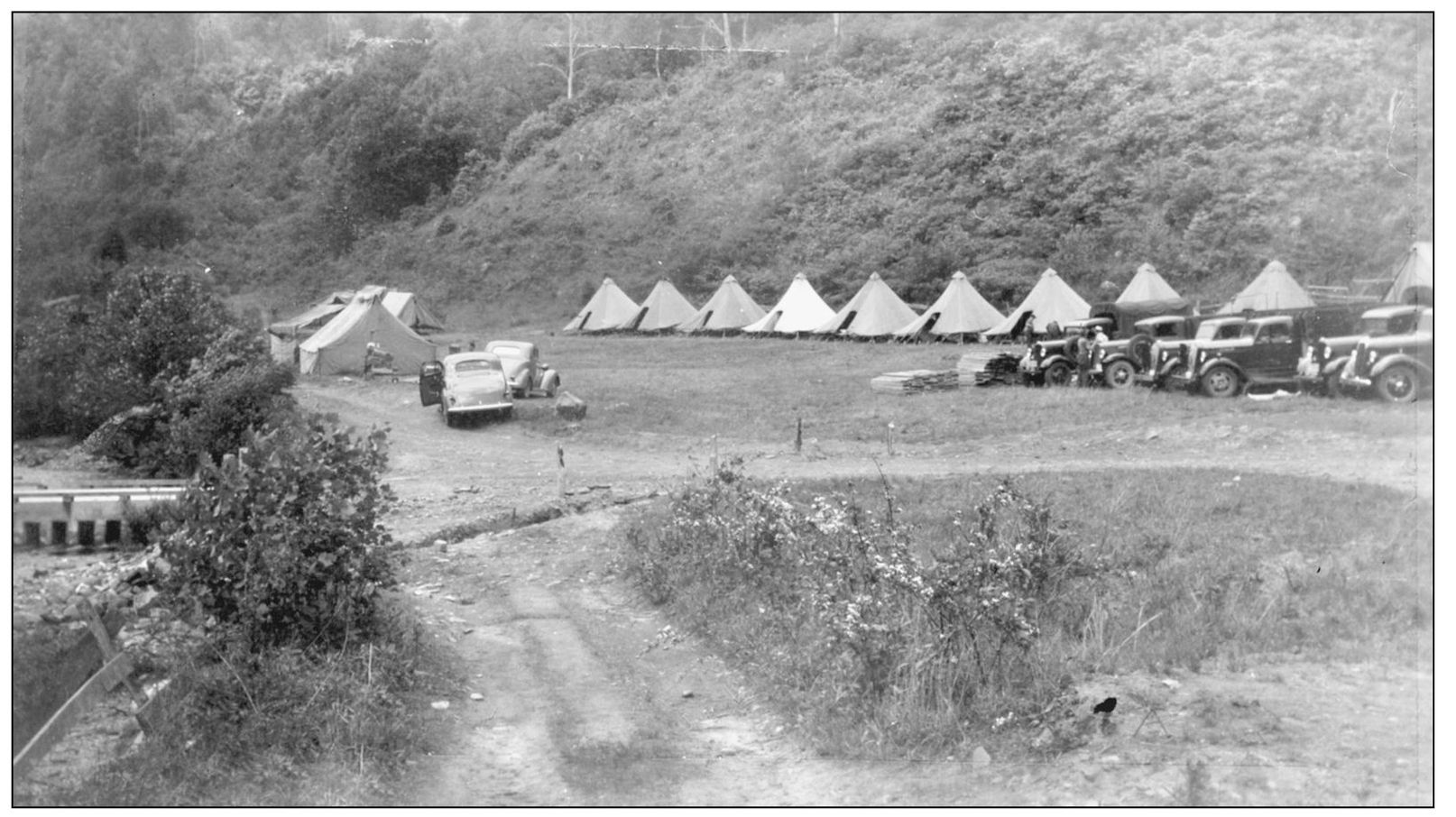

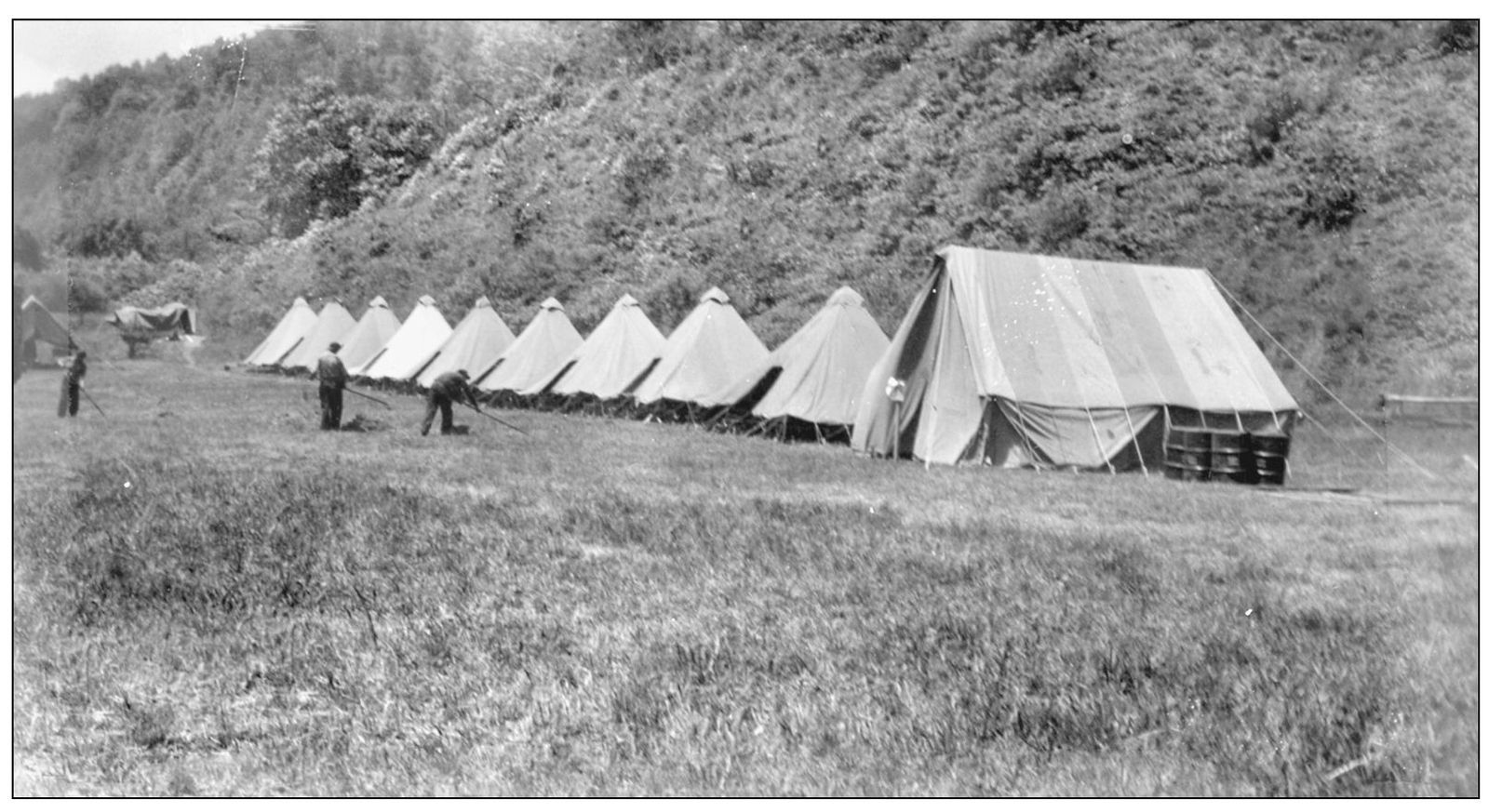

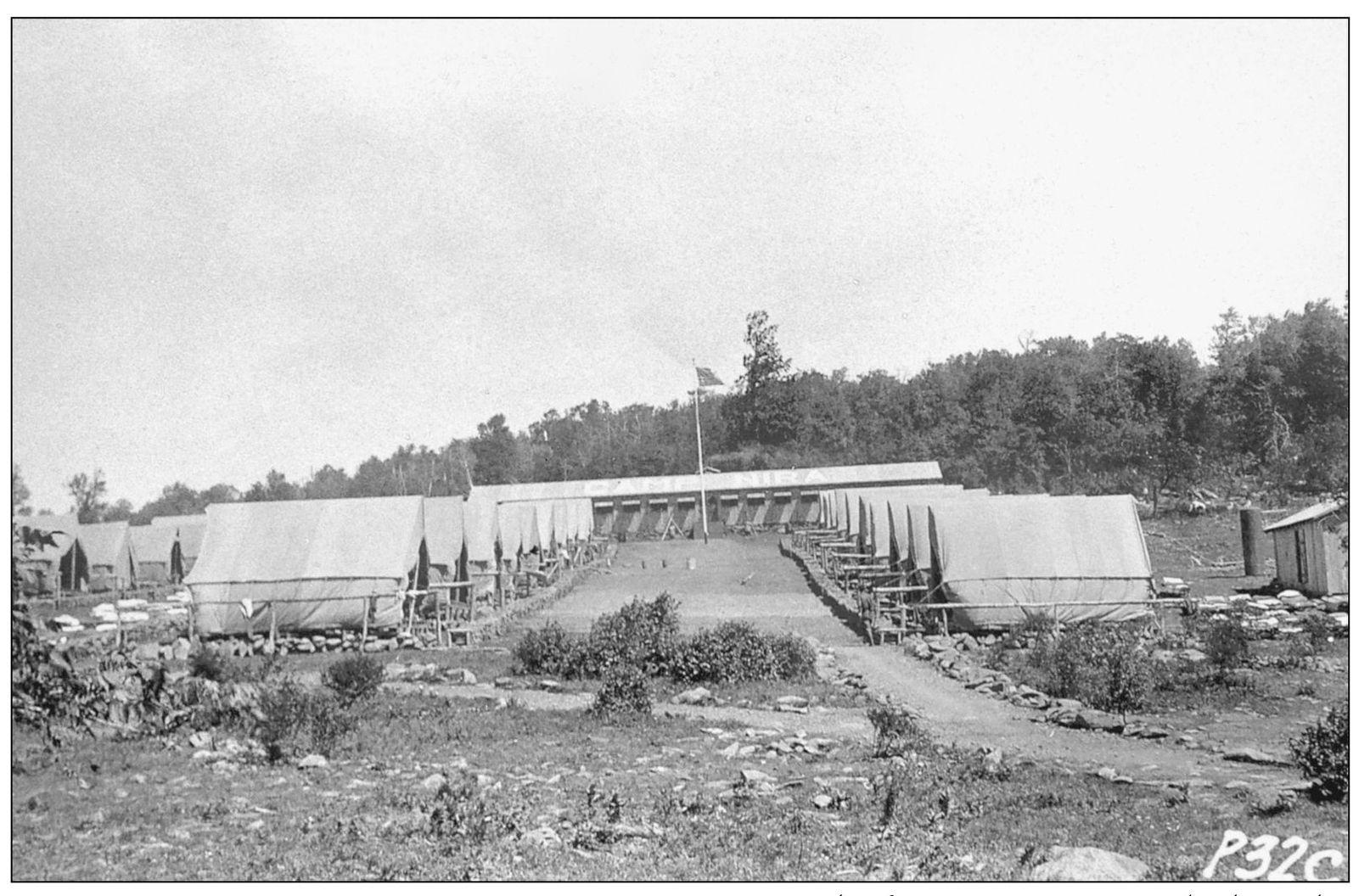

ROCK CASTLE GORGE ON MAY 23, 1938. The tents indicate that the camp was very young in development. They were started with heavy army tents until facilities could be built to house the men. Grass had to be mowed and brush had to be cleared to keep the camp inhabitable. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

BLACK CAMP GAP ON AUGUST 20, 1935. Located at milepost 3.3, the Black Camp Gap boasted at least 21 tents when first built. The tents were bigger than the Model T sitting to the right. With the flaps open it would appear that it was pretty hot in August 1935. A cool summer breeze probably brought much needed relief. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

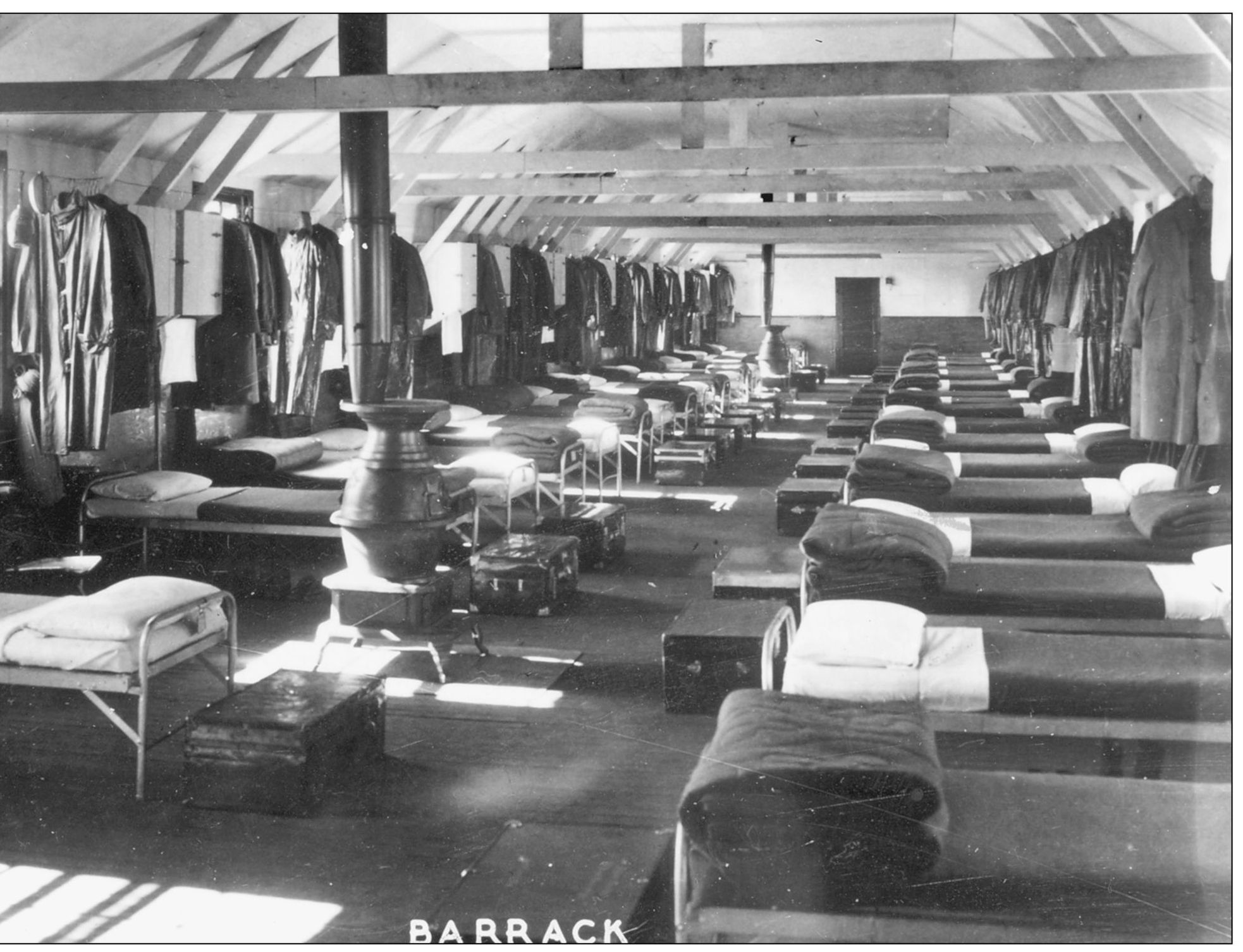

CAMP BARRACKS IN NOVEMBER 1948. Neatly made beds lined the barracks of the Peaks of Otter Camp. Work from the forestry division at Kelso, Virginia, was transferred to the Peaks of Otter in 1934. The men were involved in remediating fire hazards and selective landscaping. They also constructed the James River CCC camp in 1941. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

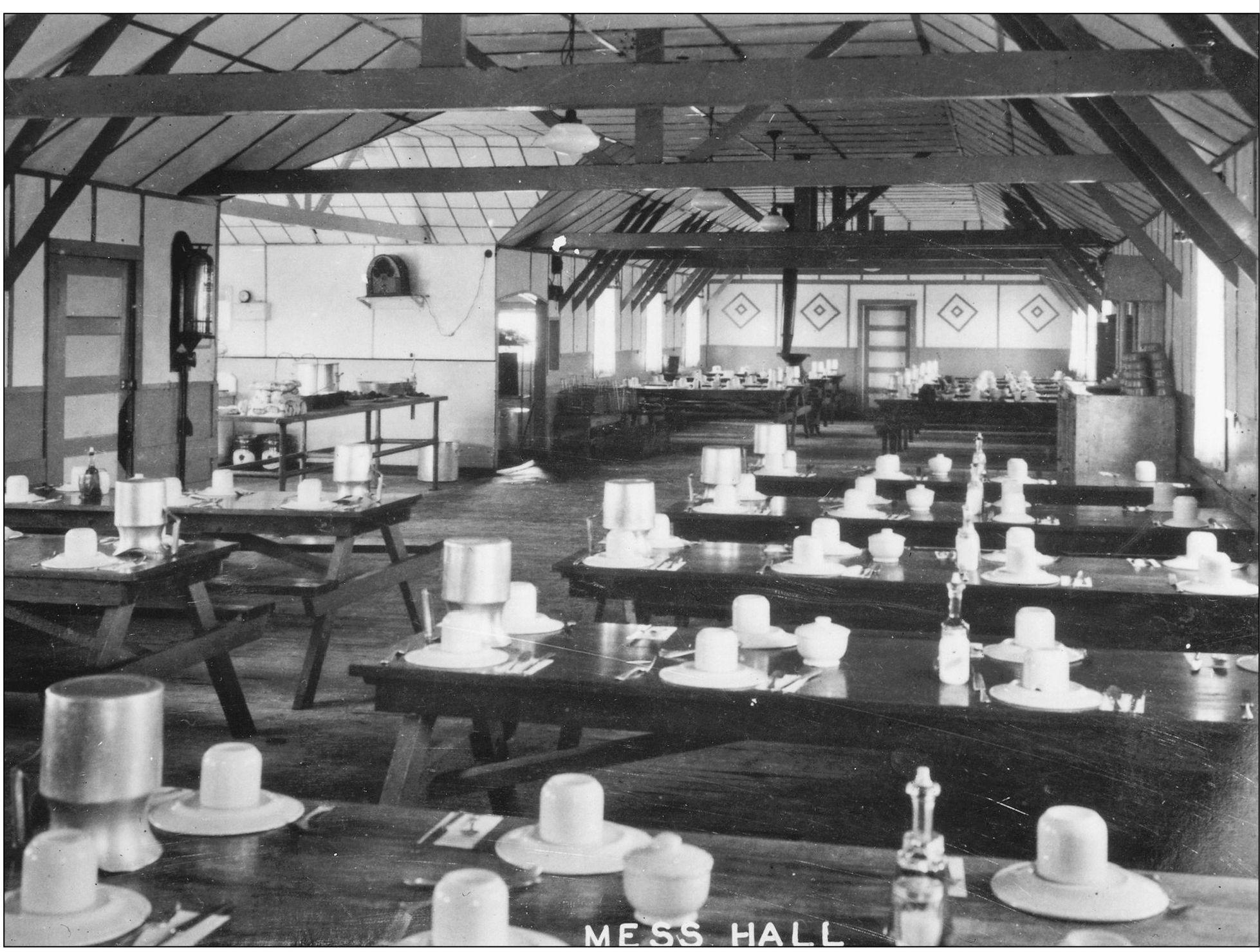

PEAKS OF OTTER MESS HALL IN 1948. Nourishing hot meals were provided for dinner every day and sometimes for breakfast. Lunch was usually a sandwich with a piece of fruit or pie for dessert. This mess hall has the tables set with coffee cups, plates, and napkins. Packaged buns are stacked on the table, waiting on the next meal. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

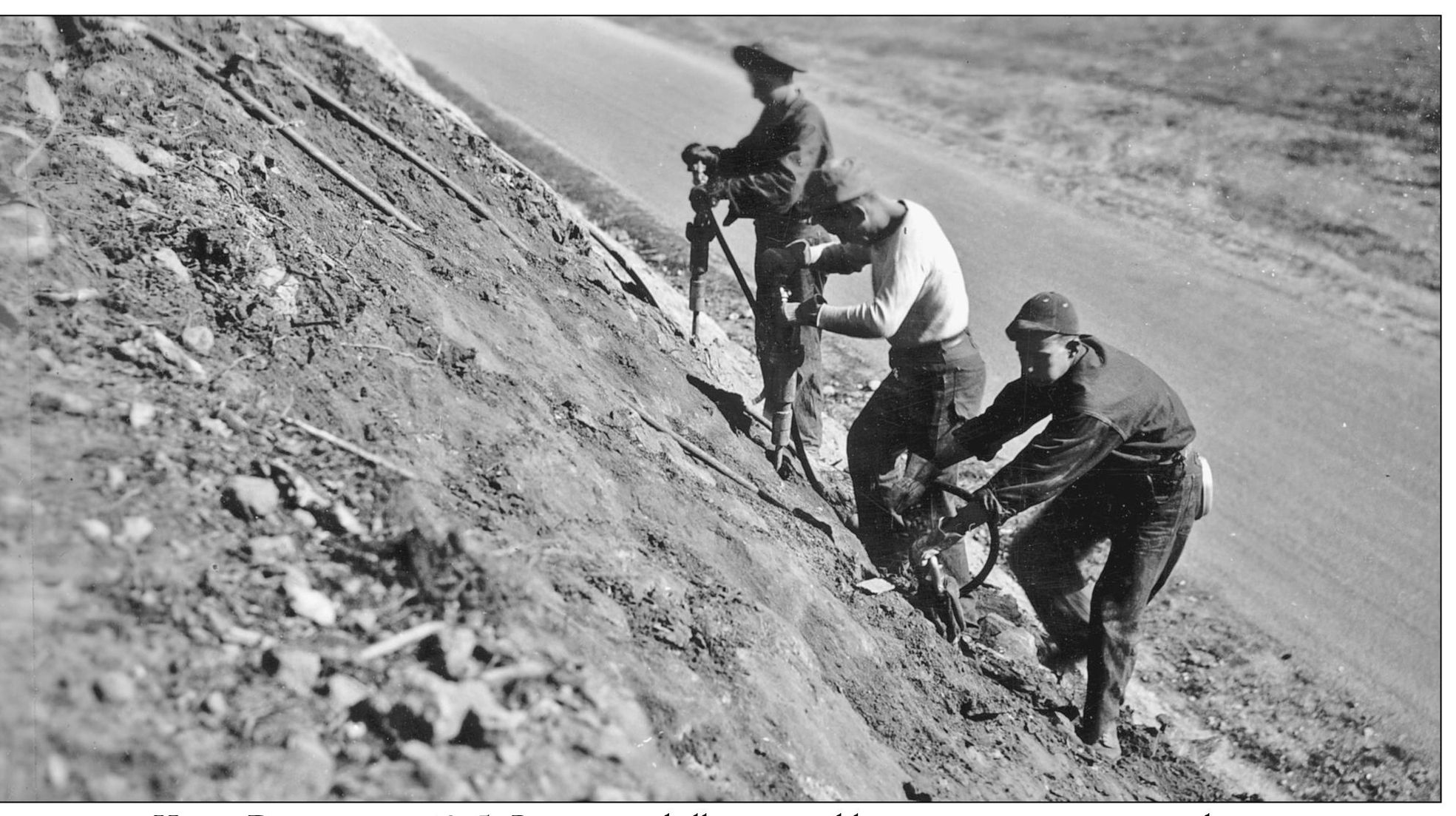

HAND DRILLING IN 1935. Pneumatic drills, powered by air compressors, are used in open excavation to drill holes into solid rock. A steel bit and shank is pounded and turned by air-power to bore the hole. The earliest pneumatic drills were hand-held or mounted on stands, singly or in groups. Known as “sinker drills,” hand-held drills are still used today in specialized applications. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

CAMP NIRA IN THE SHENANDOAH VALLEY IN 1933. The first CCC camp was built in the Shenandoah National Park (not the Blue Ridge Parkway). Later some of the trained men became park rangers for the Blue Ridge Parkway. (Courtesy of the Shenandoah National Park.)

GROTTOES CPS CAMP IN 1941. Camp Grottoes was the fifth Civilian Public Service (CPS) camp built in the Shenandoah National Park. It was located in Virginia. The camp was active during World War II and up until 1947. (Courtesy of the Shenandoah National Park.)

ROCK CRUSHER IN AUGUST 1936. Before construction could get too far under way, rock crushers had to be set up at various locations to provide the necessary crushed gravel to make the roadbed. This crusher operation was located near milepost 150.5 in Virginia. When possible, they recycled local rock into the roadbed. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)