Five

WATER AND ARCHITECTURAL FEATURES

Distinctive architectural water structures of the Blue Ridge Parkway include the collection of bridges and grade-separation structures. They allow the parkway to cross streams and other roads. Many of these 170 structures are arch-type bridges with rustic stone facades, allowing them to blend into the mountain landscape. Much of the stone was gathered locally by the contractors. Some of the bridges are steel and concrete.

During the early design phase of the parkway, the Bureau of Public Roads (now the Federal Highway Association) collaborated with the National Park Service on the design of the structures.

Stone facing for the bridges and grade-separation structures became the hallmark style of architecture used by the National Park Service. Rock was either acquired from local quarries or obtained from the rock cuts created during the road construction. The stone varies on the 469-mile route depending on the geology of the surrounding area.

An arch bridge is a bridge with abutments at each end shaped as a curved arch. Arch bridges work by transferring the weight of the bridge and its loads partially into a horizontal thrust restrained by the abutments at either side.

Several different arch-type bridges were built along the parkway. The landscape dictated the length and span of the arches. An elliptical arch was used when there was sufficient horizontal clearance. This allowed the arch to be carried all the way to the ground. In some situations, circular arches were employed for narrower spans. Crossing streams and rivers sometimes called for a skewed curved bridge on the diagonal.

Culverts and drains were formed in similar fashion, with stones covering the fronts and sides of the culverts. The stonework was not merely cosmetic but helped form the concrete frame.

The parkway has 26 tunnels. They are arched shaped and stone faced like the bridges.

Several dams were built along the parkway for holding ponds, fishing ponds, and reservoirs.

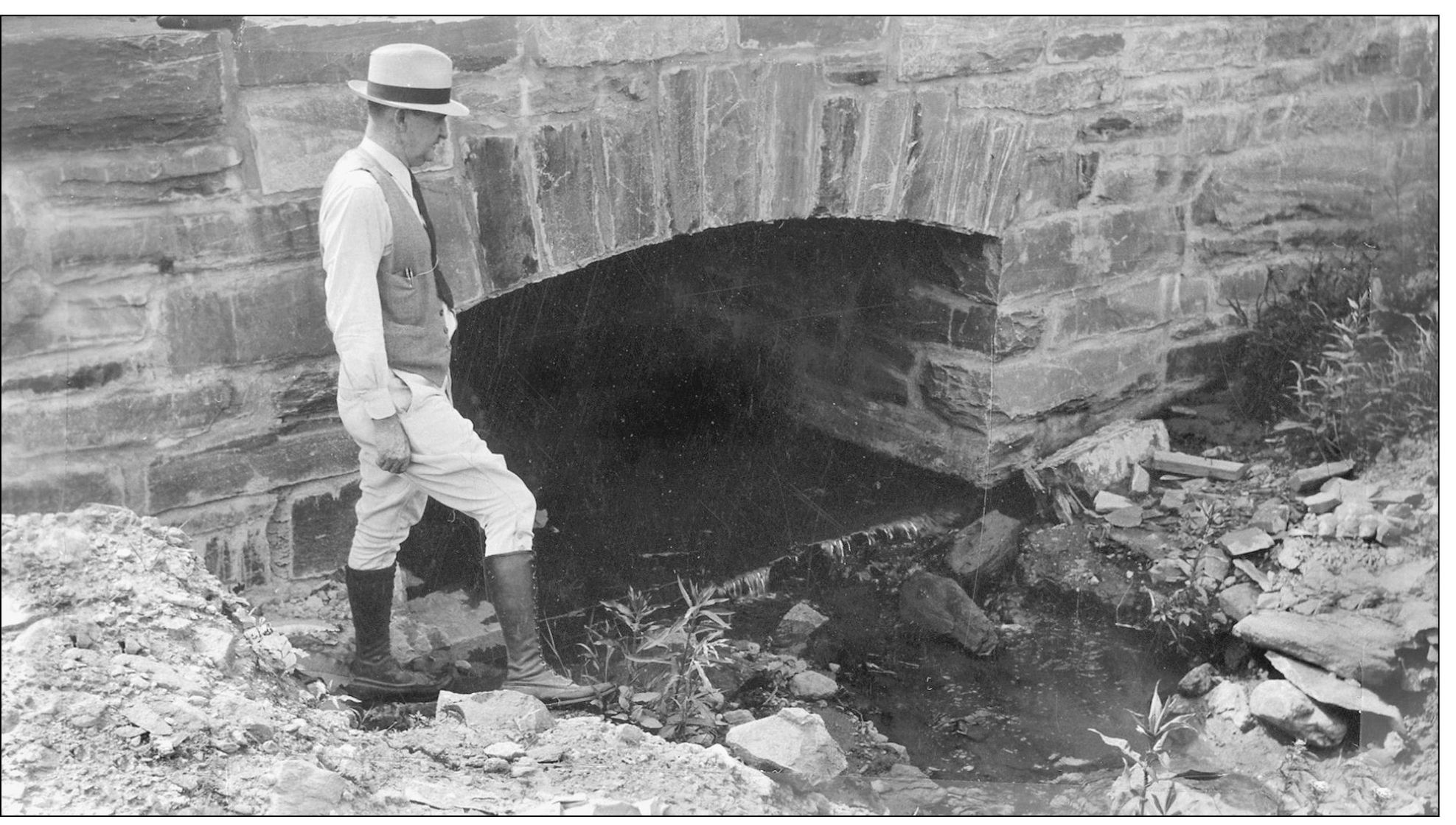

THE FIRST BOX CULVERT. This box culvert measures 4 feet by 6 feet and is located at milepost 229 in North Carolina just south of Cumberland Knob. More than likely this is one of the first culverts built on the Blue Ridge Parkway. A contractor would have built this culvert, not the CCC. Box culverts were designed to be sturdier than corrugated piping and would hold a higher volume of water. Most of the culverts found in the early construction of the parkway are natural-bottom culverts with sand, gravel, and dirt of the native creek beds as the bottoms. They were three-sided structures. An environmental plus to these culverts is that they allow fish passage. For the trout streams found in the Blue Ridge Mountains, this is important. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

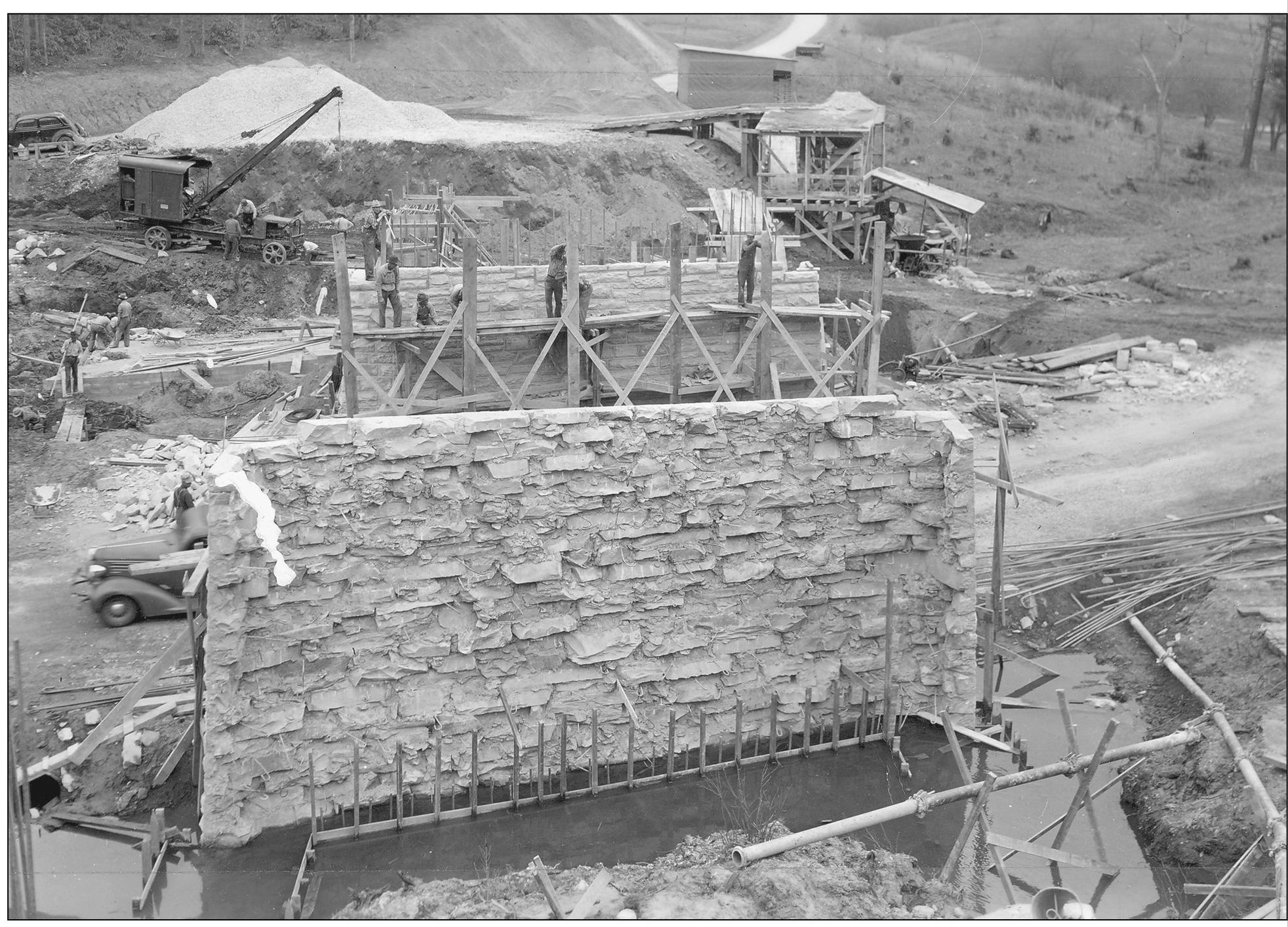

LINVILLE OVERPASS, c. 1939. Located near milepost 317.5, this overpass was probably completed sometime in 1940. Notice the old tractor crane in the background. All bridges and overpasses had to be covered with native stone. A cement factory was set up on-site. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

HEADWALL CULVERT IN 1936. Built near the Virginia and North Carolina line between 1935 and 1936, this is a great example of a headwall culvert. It is covered with native stone and has an arch over the single opening. Drainage is the main purpose of this culvert. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

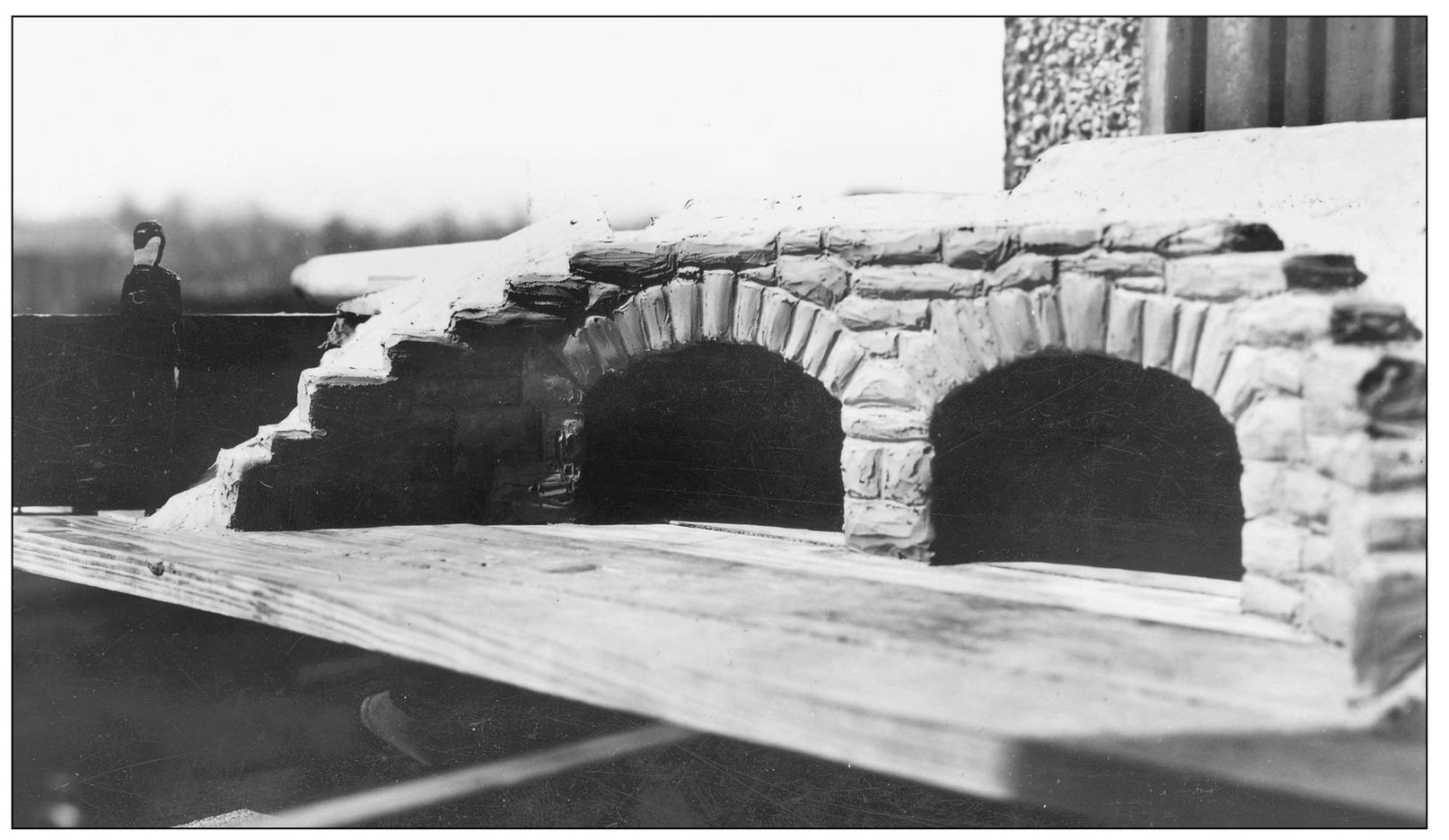

DOUBLE-BOX MODEL. Engineering models of the culverts were built by the engineers. This model is of a double-box stone masonry culvert and was built in 1935. Native stone was laid on the face of each culvert to give it a more uniform, finished look. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

MODIFIED TYPE 3 CULVERT. Grading complete, this culvert was modified and displays side wings of stone walls. Located in Virginia at milepost 148, between Pine Spur overlook and Smart View, this culvert was completed in December 1936. A small stream flows through this culvert, which explains why extra space was needed. Culverts are engineered with many factors in mind. These factors are normal stream flow and heavy flow after rainfall. Sometimes the size of the stream and fish species has to be considered to allow enough space for the fish migration to spawn. Formerly, these streams would have been called a “ford,” with either a low water bridge or nothing at all to drive over. When flooding occurs, water goes over the low water bridge. The idea behind culverts and low-water bridges is that they are safe under normal conditions to cross. Under flooding conditions, the pathway may be impassable. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

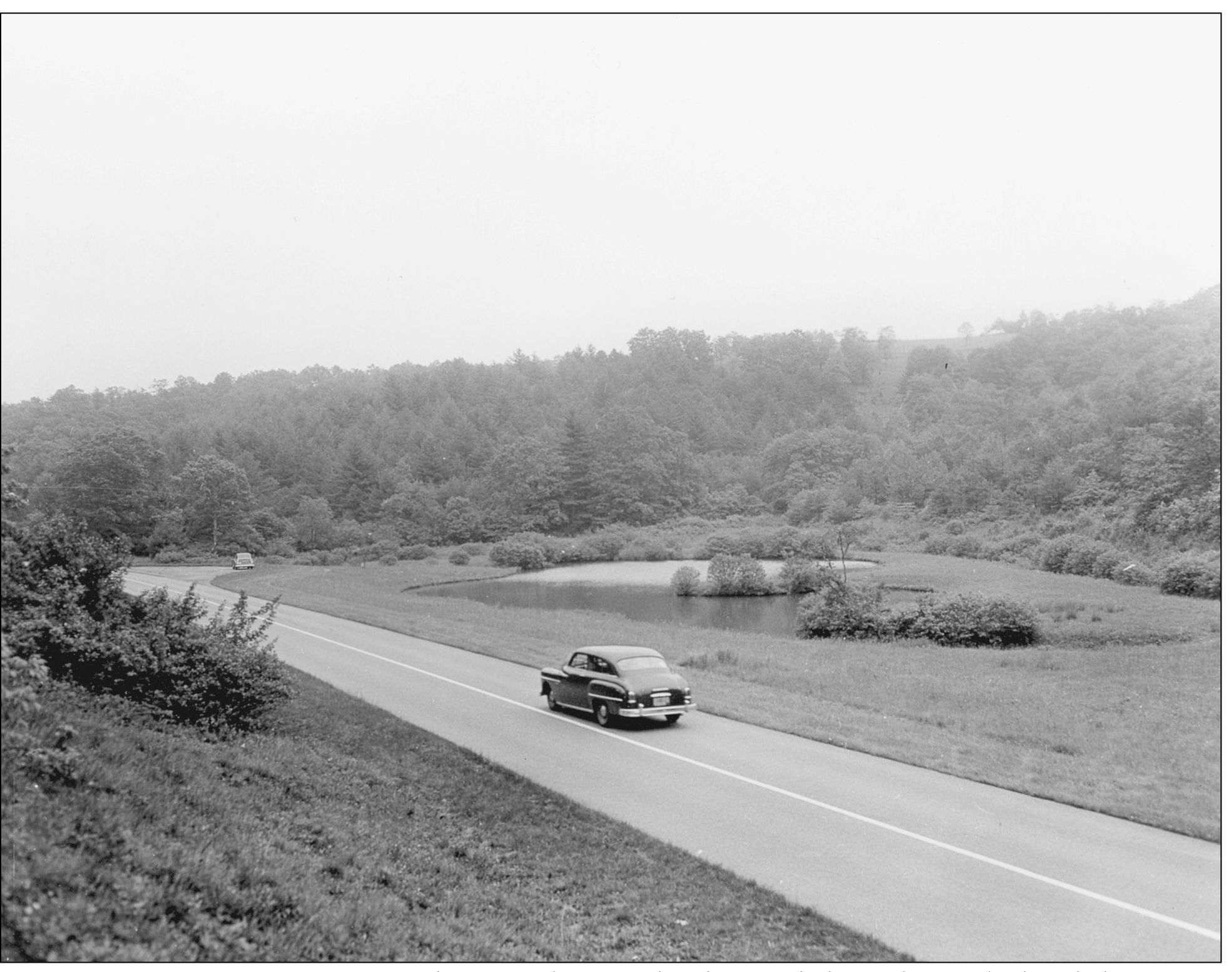

THE FISHING HOLE. Snapped in September 1953, this photograph shows a beautiful fishing hole on the parkway. Some water projects were natural to the parkway and were only landscaped, while damming up streams created others. This one has a wonderful picnic area and parking lot. The designers of the parkway wanted to create “atmosphere,” and they did this quite often with water features like this small pond. Visitors would have to have a permit to fish here. Some of the ponds and streams are stocked. Special fishing spots in Virginia include Mill Creek, Abbott Lake, Little Stoney Creek, Otter Lake and Creek, Rock Castle Creek, Little Rock Castle Creek, and Chestnut Creek. North Carolina fishing spots include Trout Lake, Upper Boone Fork (upstream from Price Lake), Lower Boone Fork, Cold Prong Branch, Laurel Creek, Sims Pond and Creek, and Camp Creek. Fishing is not permitted from the dam at Price Lake, from the footbridge in the Price Park picnic area, or from the James River Bridge. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

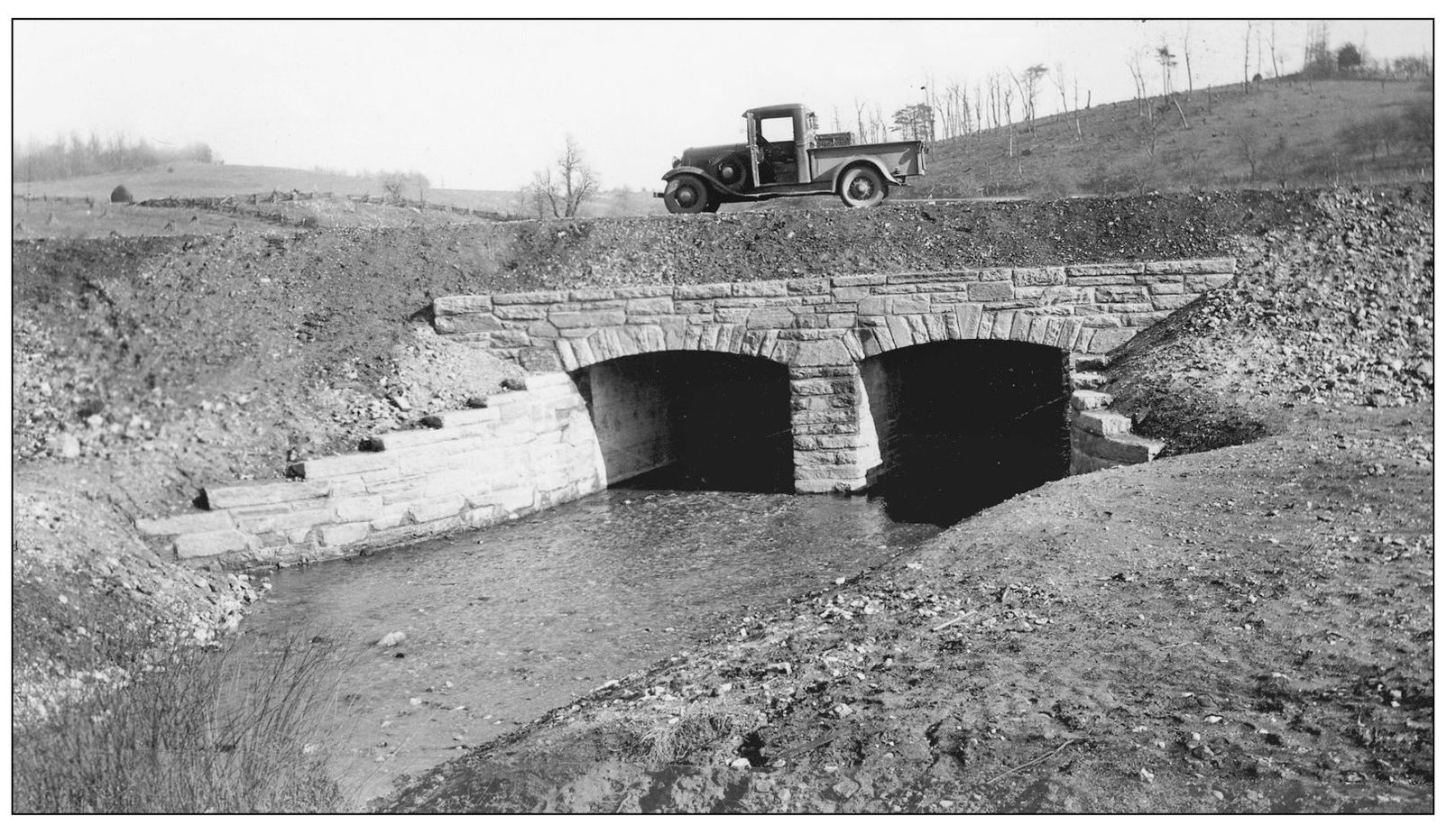

DOUBLE-BOX CULVERT IN 1936. A rather heavy-flowing stream flows through this double-box culvert near milepost 150 in Virginia. Between Pine Spur and Smart View, this double culvert was completed sometime in 1936. The old Ford Model T truck has spoke wheels and was based on the car Model T. They were mass-produced between 1925 and 1927. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

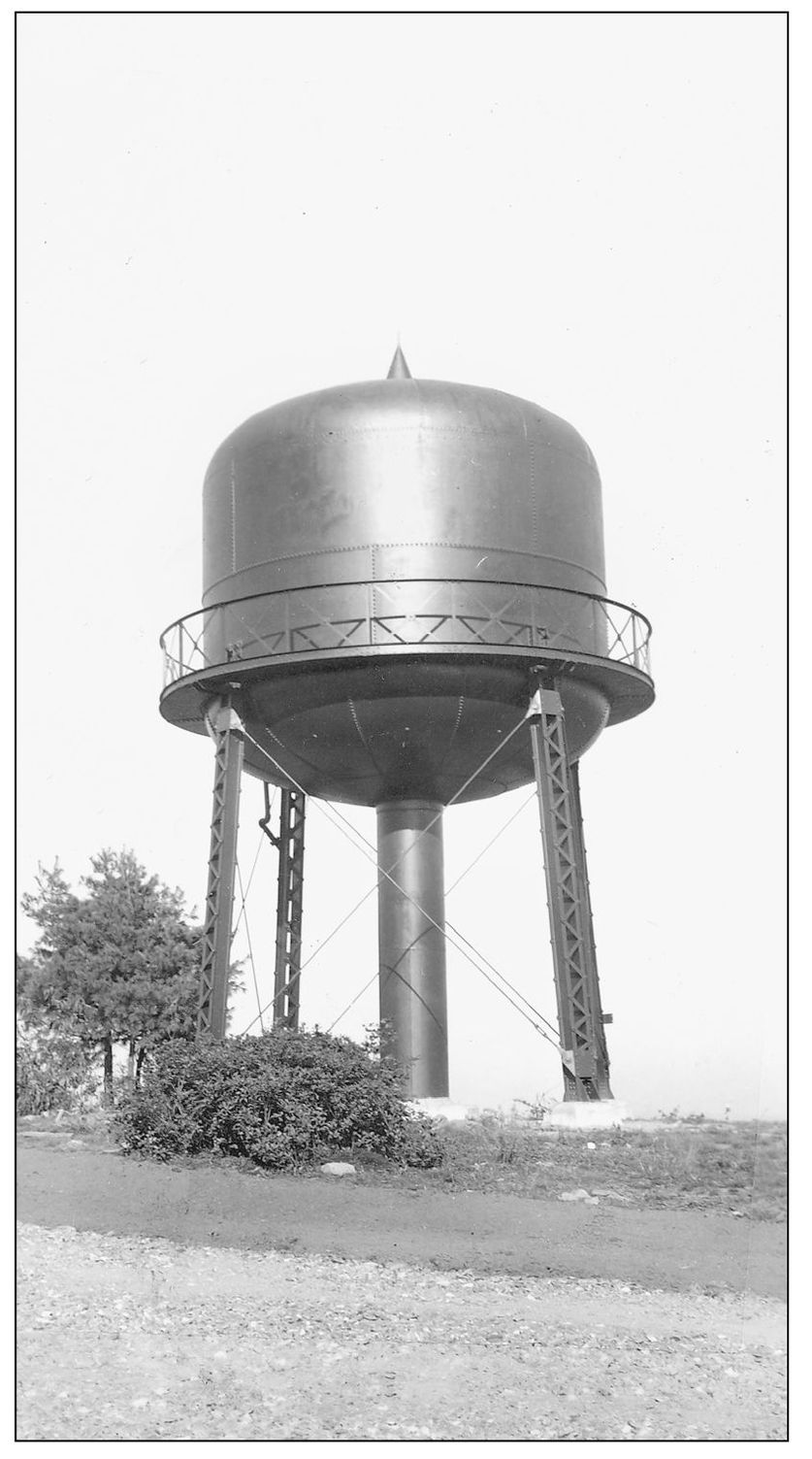

DOUGHTON PARK WATER TOWER. The storage tank at Doughton Park was erected in 1938 and provides storage today. This is a great lookout point for photographers. Doughton Park used to be called the Bluffs but was renamed after Sen. Robert Doughton, who was instrumental in the parkway path through Alleghany County, North Carolina. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

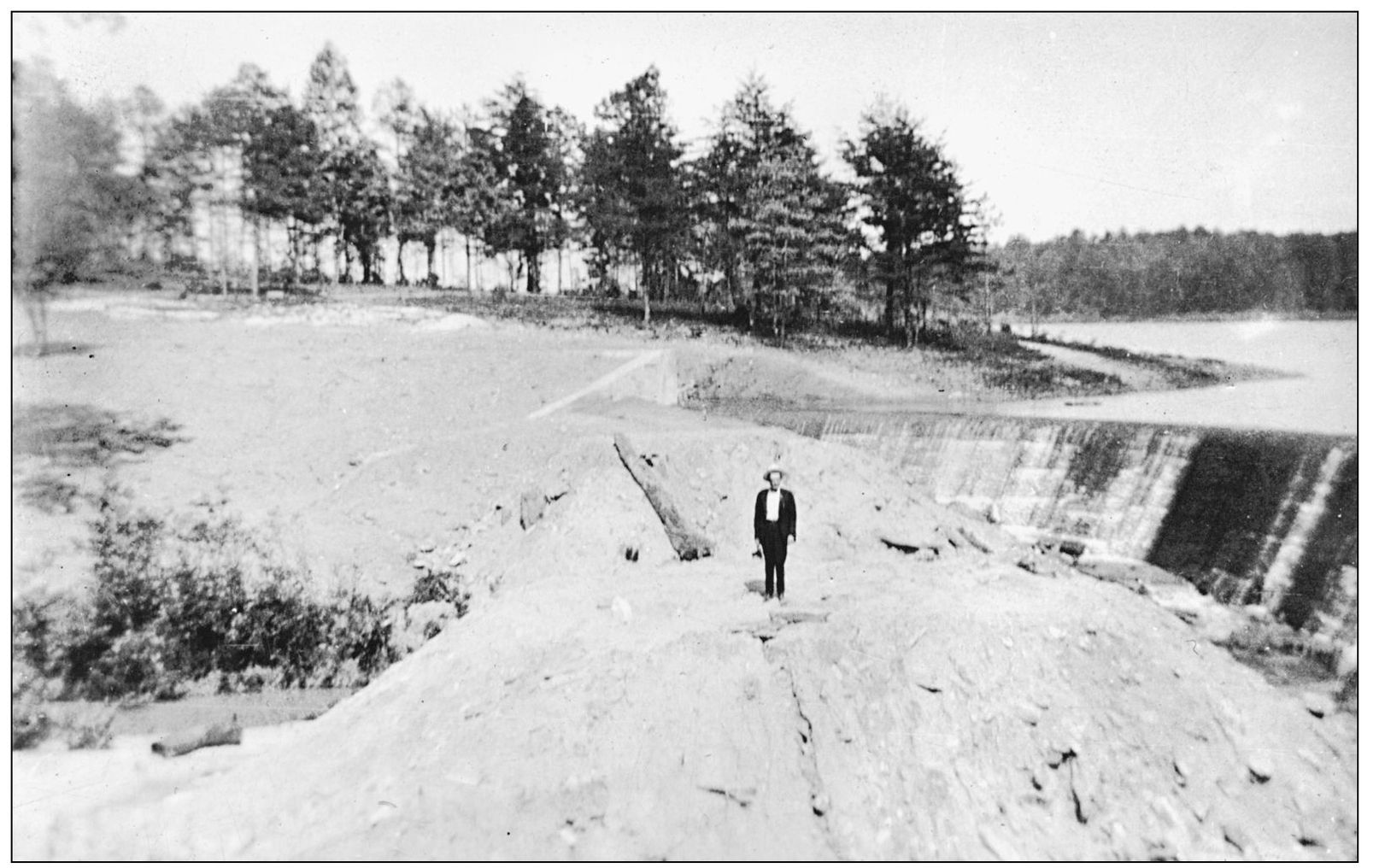

EARLY NORTH CAROLINA DAM. The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) was another public works program and built dams in Eastern Tennessee and Western North Carolina. This dam is probably the Lake Junaluska Dam, c. 1930. The parkway has 14 dams; the parkway dams are not as large as the electrical dams built by the TVA but are just as impressive. (Courtesy of a private collection.)

DAM CONSTRUCTION, C. 1930. Located in the Western North Carolina mountains, this dam was constructed sometime in the 1930s during the boom in public works construction. They provided power for the electricity that would be supplied to homes and businesses, and they provided a good supply of water. (Courtesy of a private collection.)

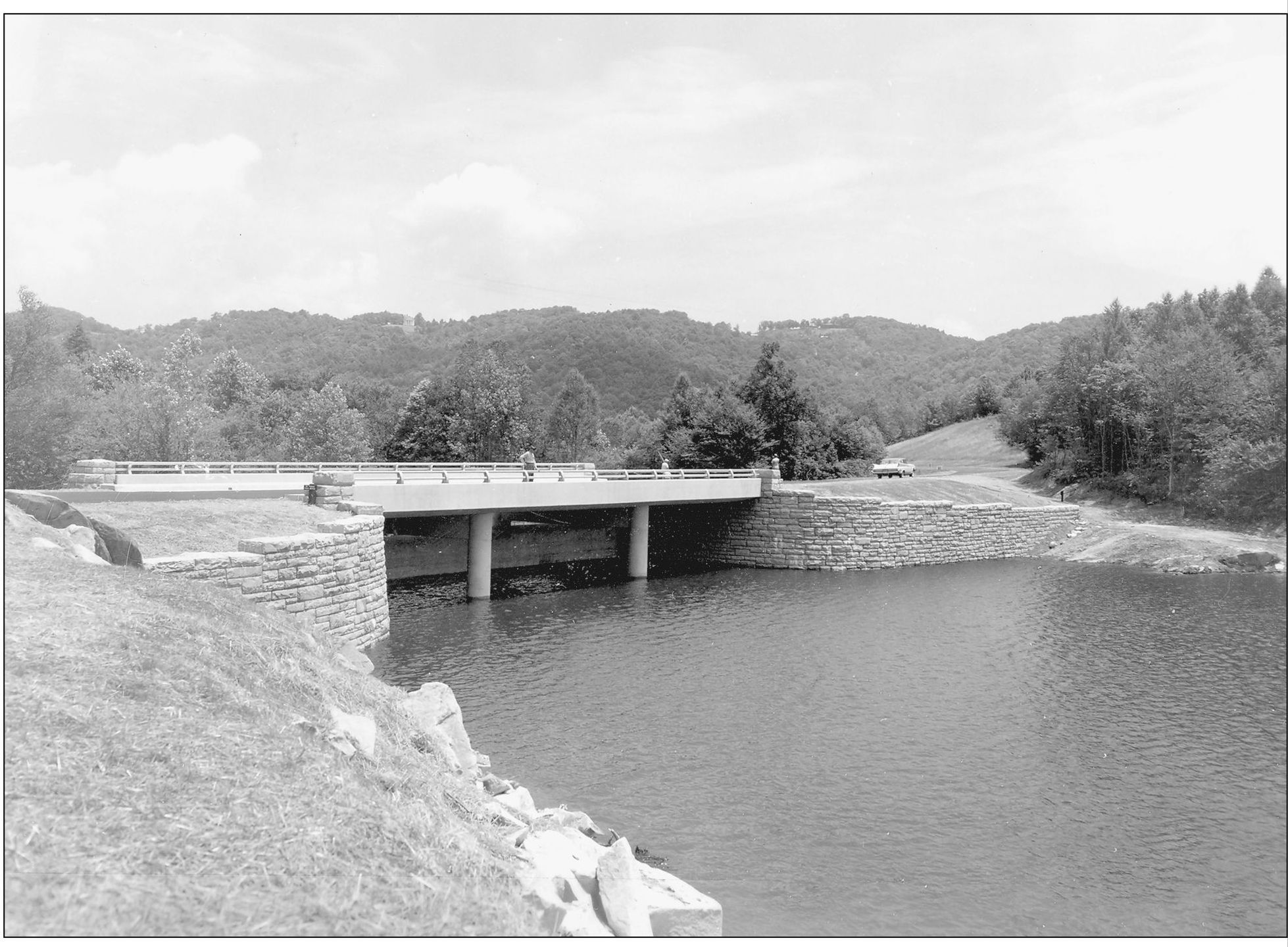

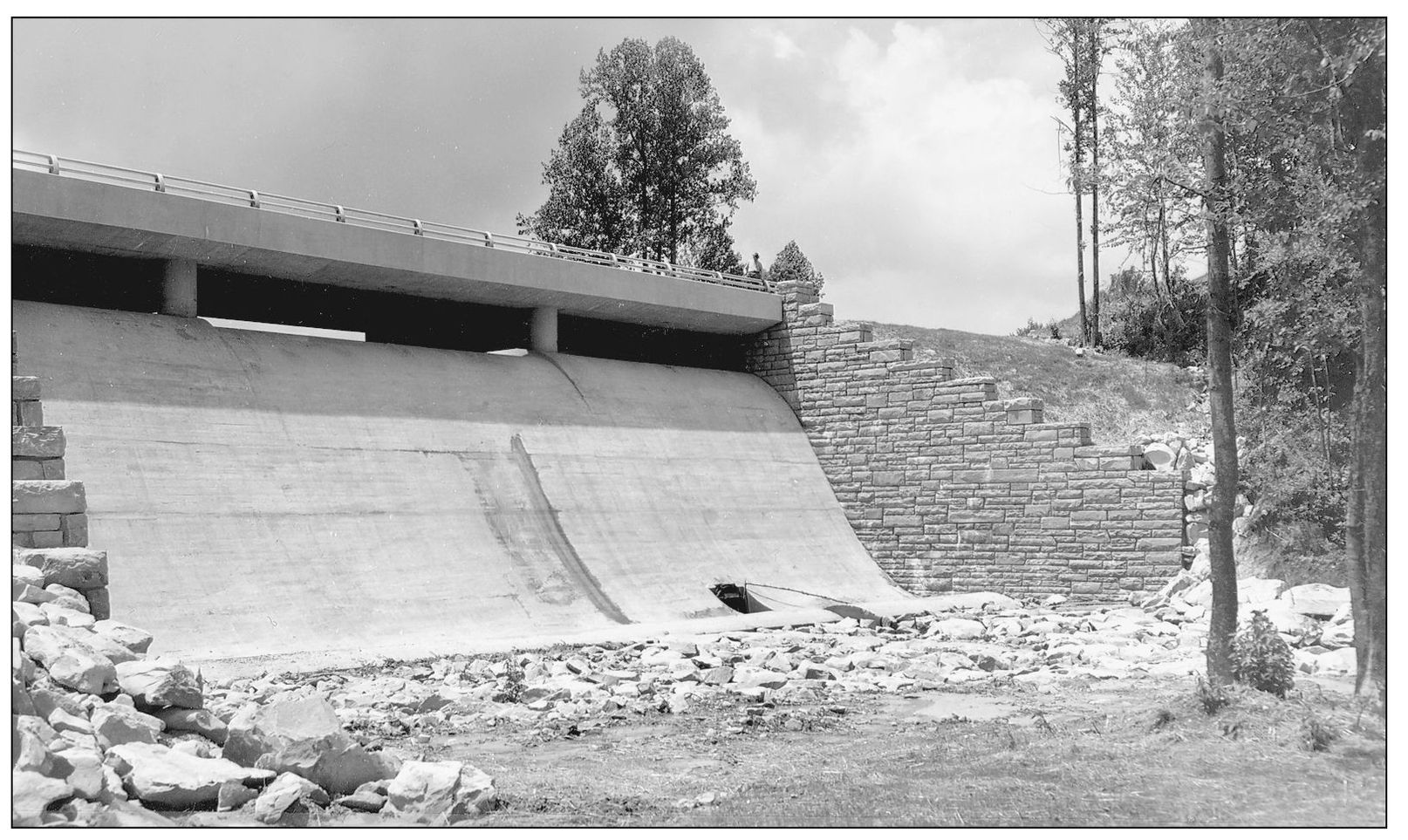

PRICE PARK DAM LOWER SIDE. The Julian Price Memorial Park was named after the late Julian Price, who was for many years president of the Jefferson Standard Life Insurance Company of Greensboro, North Carolina. The park is composed of 4,200 acres. The company and Price’s son and daughter, Ralph C. Price and Mrs. Joseph McKinley Bryan, cooperated in the acquisition and dedication of this property as a public recreation area. It is one of the largest developed campground areas on the parkway with 129 tent and 68 RV sites, and those on Loop A are located next to Price Lake. Interpretive programs, fishing, boat rentals, and an extensive trail system, including the Tanawha Trail across the face of Grandfather Mountain, make for a delightful parkway visit. This section of the parkway is located next to the Moses Cone Memorial Park. Blowing Rock and Boone are the nearest towns. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

PRICE PARK DAM. Located at milepost 296.8 on the Blue Ridge Parkway is the Julian Price Lake Dam. Constructed in 1960, this photograph shows the dam from the upper side. Today it is one of the most popular spots on the parkway for camping and fishing. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

SIMS POND AT MILEPOST 295.9. Sims Pond and Creek are located next to the Price Park and Lake. Parking and accessible trails lead the visitor to this beautiful pond. A one-mile trail has been developed around the pond. Fishing is allowed. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

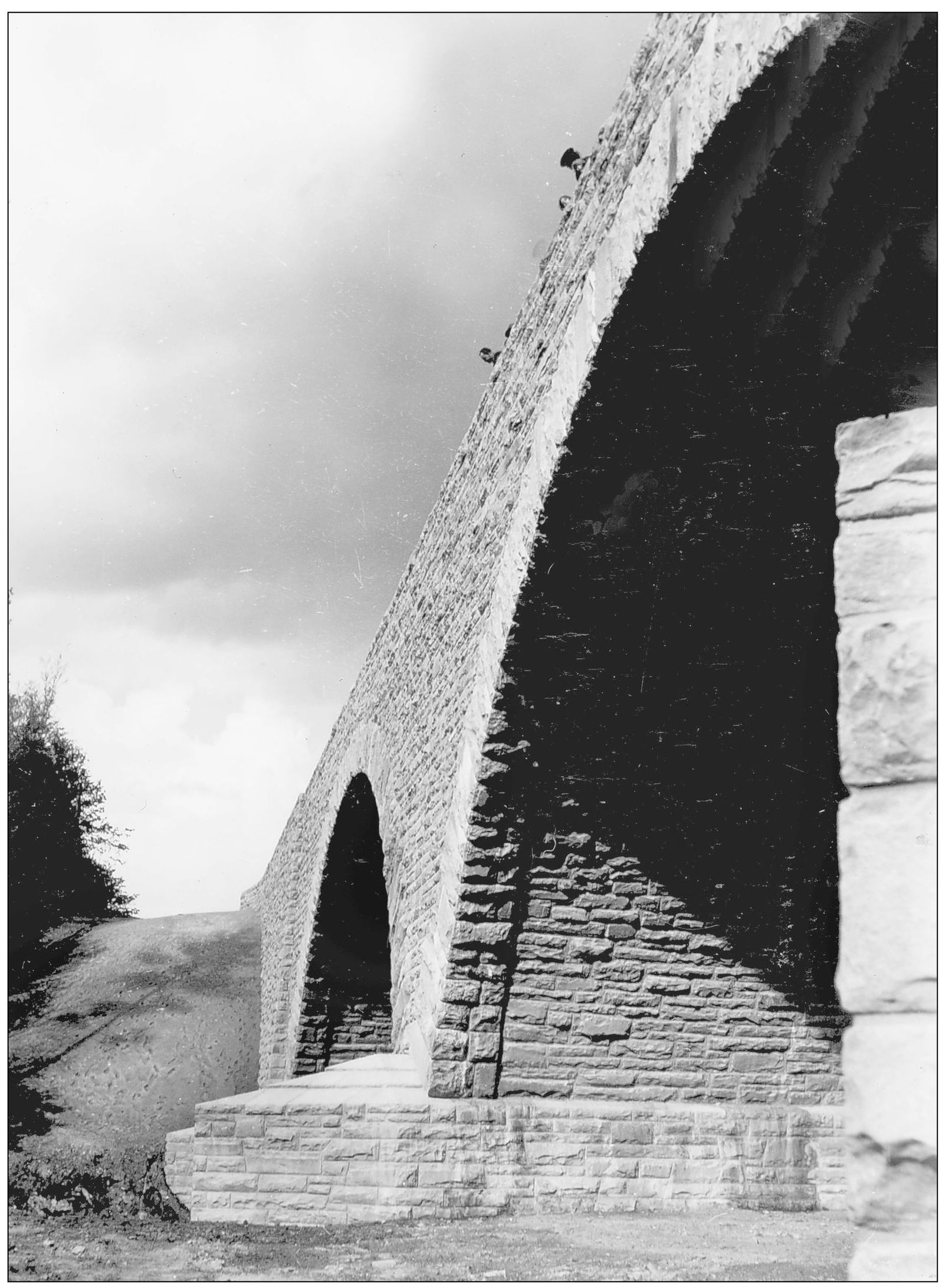

LINVILLE RIVER BRIDGE. Built in 1941 at milepost 316.6, the Linville River Bridge is the largest stone structure on the Blue Ridge Parkway. Distinctive of parkway construction are the 168 structures that allow visitors to pass over streams, rivers, and ravines; they are covered with rustic stone to blend in with the landscape. Others are sleek modern steel-and-reinforced-concrete structures. The old stone arch bridges were constructed by erecting stone arch rings, abutments, and abutments and spandrel walls, and then pouring concrete on a large network of steel reinforcing rods. Not only decorative, the stonework provides form for the concrete frame. All but one of the overpasses are stone-faced-arch structures. Stone-facing structures became a hallmark of the National Park Service during construction. Generally, stone was obtained from local quarries, creating the variance of stone types depending on the location of the structure. Different shapes were employed, with choice being dictated by the length and span of the ravine or river. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

LOOKING UP! LOOKING DOWN! The Linville River Bridge is one of the most awe-inspiring engineering structures on the Blue Ridge Parkway. Here, in June 1940, visitors are touring the new structure and wondering, “Where is the water?” Today a one-tenth-mile trail leads to the structure where the Linville River flows out of the Linville Gorge. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

ELLIPTICAL ARCH BRIDGE. A winter blanket covers this skewed elliptical arch bridge that has a stone face. The single arch provides water flow for a small creek. Some of the arches were skewed on a diagonal so as not to disturb the flow of the roadway. This created an amazing bridge. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

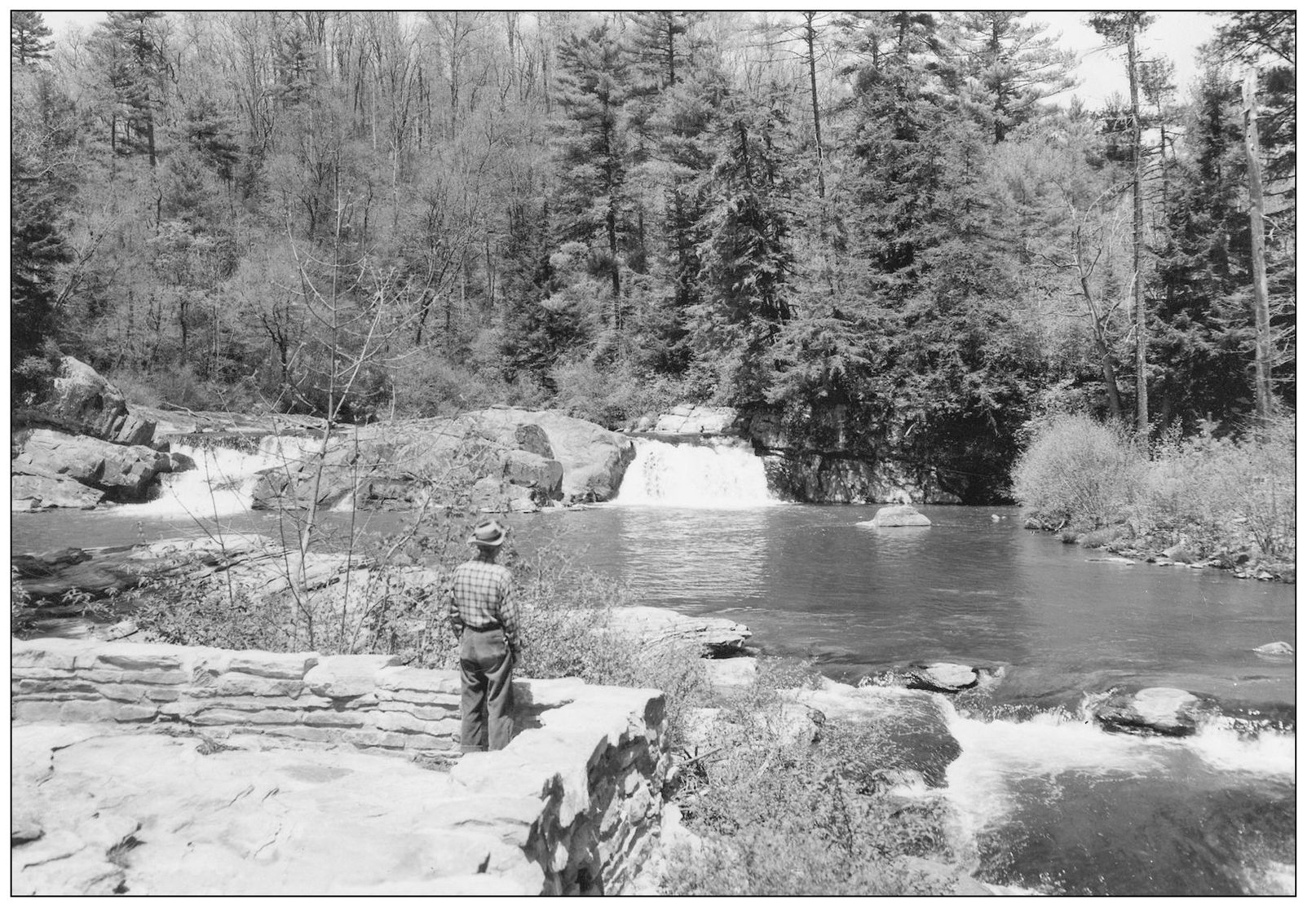

LINVILLE FALLS. Surrounded by towering hemlocks, the Linville Falls were created by a rare geological phenomenon in which older rock overlay younger rock—evidence of ancient collisions between the North American and African continents. This is the lower basin of the falls. Purchased with funding from John D. Rockefeller, Linville Falls is a favorite spot for the author. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)

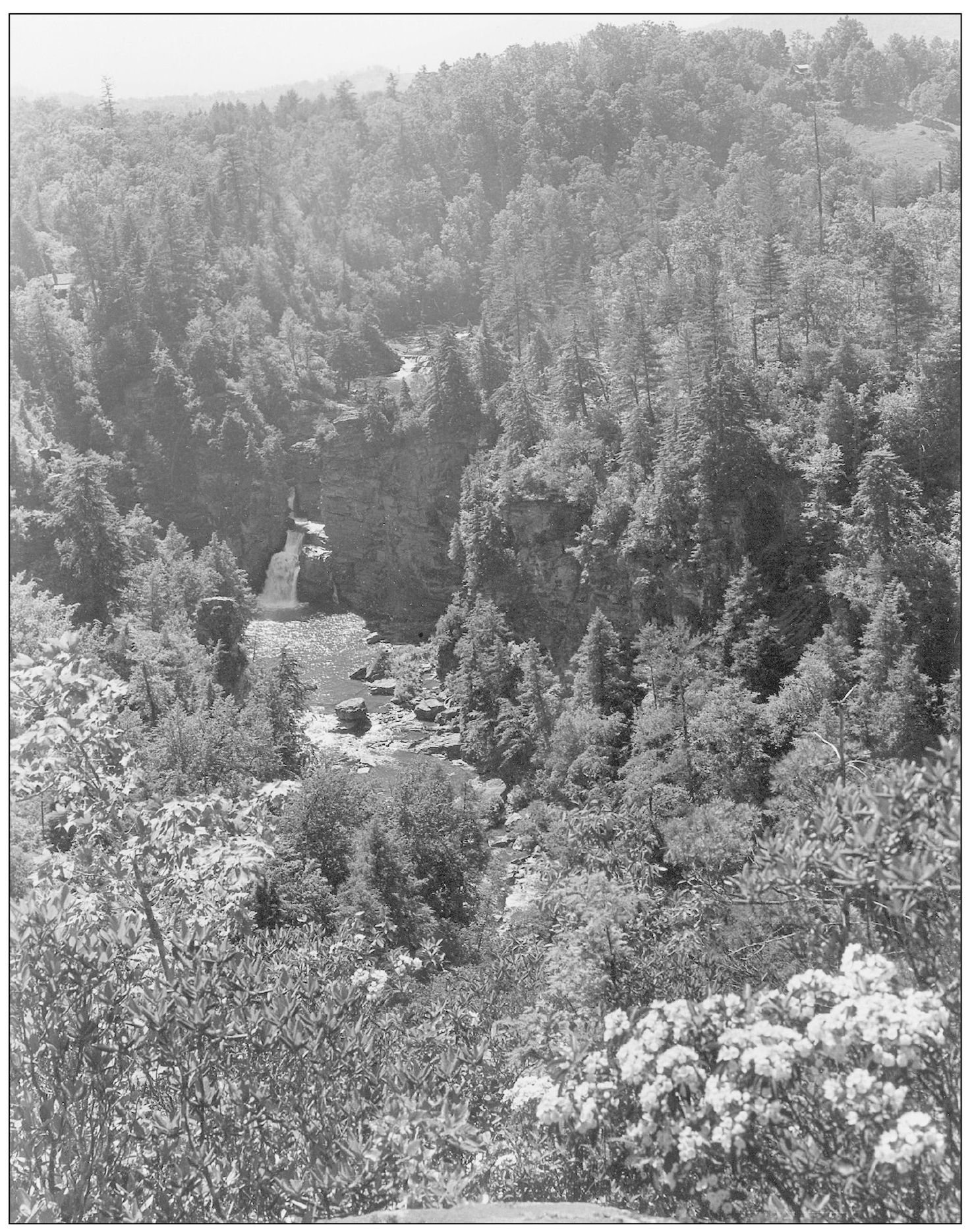

ERWIN’S VIEW OF LINVILLE FALLS. Milepost 316.4 boasts the powerful Linville Falls, which, as Representative Doughton said during his negotiating for the path of the parkway, was “Chiseled by the Omnipotent Architect of the World ... [God] has carved the most outstanding display of nature known to all creation.” Now one of the largest natural attractions of the parkway, Linville Falls can be viewed from several balconies. Instead of several falls on one trail, this site offers six different views and three different trails for one superb waterfall. Linville Falls has a double cascade with a vanishing act between the two falls. Headwaters of the Linville River are at Grandfather Mountain. It flows to the Catawba Valley and into the Catawba River. The Cherokees called the area “Eeseeoh,” which means “river of cliffs.” Settlers called the river and the falls “Linville” to honor the explorer William Linville, who in 1766 was attacked and killed in the gorge by Native Americans. (Courtesy of the Blue Ridge Parkway Archives.)